Abstract

Our study focused on assessing disease and pregnancy outcomes in Thai patients with Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder (NMOSD), a condition that disproportionately affects women of childbearing age and poses risks to both mother and fetus. We retrospectively analyzed eight NMOSD patients with a total of 10 pregnancies from our central nervous system inflammatory demyelinating diseases (CNS-IDDs) registry. Over a 12-months spanning from before pregnancy to 12 months postpartum, we observed 13 relapses, with a notable 76.92% occurring postpartum. The mean annualized relapse rate (ARR) peaked at 1.2 (SD ± 1.93) during specific postpartum intervals (0–3 and 6–9 months postpartum), significantly increasing from 0.20 (SD ± 0.42) in the 12 months before pregnancy (BP) to 1.00 (SD ± 1.49) during the 12 months postpartum (PP). Disability, assessed using the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) scores, worsened from 1.56 (SD ± 2.18) before pregnancy to 2.1 (SD ± 2.63) at six months postpartum. Maternal and fetal complications were prevalent, with six out of nine pregnancies experiencing adverse outcomes such as false labor, premature rupture of membranes, postpartum hemorrhage, intrauterine growth restriction, preterm birth, stillbirth, and low birth weight. Based on our findings, azathioprine and rituximab may be suitable treatment options for maintaining therapy throughout pregnancy, particularly in cases of high disease activity. Our study highlights the critical need for comprehensive management strategies for NMOSD patients of childbearing age. Preconception planning and counselling, along with early obstetrical consultation and closely monitored treatments during pregnancy and postpartum, are vital to mitigating pregnancy-related relapses and adverse fetal outcomes in this vulnerable patient population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) is a rare autoimmune disease characterized by the presence of pathogenic autoantibody targeting aquaporin-4 (AQP4), which is detected in the majority of NMOSD patients1,2,3. Patients with NMOSD (pwNMOSD) typically experience a relapsing course and accumulated damage from each relapse leads to disability4.

pwNMOSD with AQP4-immunoglobulin G (AQP4-IgG) positivity has a female predominance. Around 50% of the patients experience their first symptoms before the age of 40, placing them within the childbearing age bracket5. One study reported a female predominance in AQP4-positive NMSOD, with a female-to-male ratio of 23:1 for ages 15–40 years6. Our previous study shows that NMOSD is the most prevalent among Thai idiopathic inflammatory demyelinating disorders of the central nervous system (CNS-IDDs), four times more than multiple sclerosis (MS) and 6.5 times more than myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease (MOGAD), with the mean age at onset of 39.8 (Standard deviation; SD ± 17.8) years7.

The association between pregnancy and increased NMOSD disease activity is well established. The Extended Disability Status Scale (EDSS) in pwNMOSD increases significantly during pregnancy and the postpartum period8. Annualized relapse rates (ARR) vary during the pre-pregnancy and pregnancy period9. Several studies show a higher ARR during the postpartum period, notably in the first three months postpartum8,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Additionally, inadequate use of immunosuppressant (IS) treatments during pregnancy, younger age at conception, and higher AQP4-IgG titers have been identified as poor predictive factors for relapses17. Furthermore, studies show an association between disease activity and poor pregnancy outcomes in pwNMOSD9, as well as a high incidence of pregnancy complications, including spontaneous miscarriages18,19,20 and preeclampsia13,19,21.

Managing NMOSD during pregnancy is challenging due to the risks associated with immunosuppressant (IS) treatments on both the mother and fetus. Although there are some recommendations for medication use, there is no consensus on treatment decisions22.

Our study aimed to evaluate disease and pregnancy outcomes in Thai pwNMOSD and propose recommendations based on our Thai pwNMOSD cohort.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study at Siriraj Hospital in Bangkok, Thailand, by reviewing records from the Siriraj CNS-IDDs registry to identify NMOSD patients who attended the clinic between December 2011 and November 2023 and had a pregnancy history. The Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders clinics comprised adult patients aged over 18 years. The inclusion criteria specified adult patients diagnosed with NMOSD2 who had at least one documented pregnancy during or after NMOSD diagnosis and had available data covering the period from 12 months before pregnancy to 12 months after delivery for each pregnancy. Exclusion criteria included patients who did not have documented details of relapses and pregnancy outcomes, either maternal or fetal. All patients had AQP4-antibody and MOG-antibody testing by EUROIMMUN (Lundbeck). The study received approval from the Siriraj Institutional Review Board (COA no. Si 619/2011), and all procedures adhered to established guidelines and regulations. All patients provided written informed consent for research purposes during clinic visits.

Data collection

Maternal baseline, clinical, and treatment data

We reviewed charts of NMOSD patients with a pregnancy history to assess and record demographic data, time, and clinical characteristics at onset, AQP4 status, neurological symptoms, disease duration, number of relapses, and treatments. Disability accrual was assessed using the Extended Disability Status Scale (EDSS), and scores at the last follow-up before pregnancy, at delivery, and at six months postpartum were recorded. Additionally, we reviewed and recorded the history of comorbidities and IS prescribed since onset and throughout the study period.

Pregnancy data

We reviewed the obstetric history and documented data of each pregnancy, including the patient’s age at conception, pregnancy-related adverse events, pregnancy-related comorbidities, delivery details, and fetal outcomes.

Radiological data

We retrieved and assessed the brain and spine MRIs of patients who experienced relapses during the study period and recorded notable lesions.

Outcome measurements

Disease outcomes

We measured the impact of pregnancy on NMOSD activity by assessing relapse frequency and disability accrual. Relapses were noted during specific time intervals: 12 months before pregnancy (BP1: 12 − 9 months before pregnancy, BP2: 9 − 6 months, BP3: 6 − 3 months, BP4: 3 − 0 months), during pregnancy (DP1: first trimester, DP2: second trimester, DP3: third trimester), and 12 months postpartum (PP1: 0–3 months postpartum, PP2: 3–6 months, PP3: 6–9 months, PP4: 9–12 months). We calculated and compared the mean ARR corresponding to the number of relapses per patient and year using the person-years method23 for each three months, as well as for 12 months before pregnancy (BP), during pregnancy (DP), and 12 months postpartum (PP). For disability accrual, we compared mean EDSS scores at BP, delivery, and six months postpartum.

Pregnancy outcomes

We assessed the effects of NMOSD on pregnancy by maternal and fetal outcomes. Maternal outcomes included the number and type of labor and delivery complications. Fetal outcomes were evaluated based on mean gestational age (GA), mean birth weight (BW), average Apgar scores at the 1st and 5th minutes, meconium stain in amniotic fluid, fetal status at birth, and occurrences and types of fetal complications.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables (age at onset and conception, disease duration, EDSS, ARR, GA, BW, Apgar scores at the 1st and the 5th minute) were presented as the mean with SD. Categorical variables (clinical presentation, significant comorbidities, complications related to labor and delivery, fetal status, and fetal complications) were expressed as percentages. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to assess statistical significance for non-normally distributed data. The threshold for statistical significance was set as a p-value of less than 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata statistical software version 14.0 (StataCorp).

Results

Among the 196 pwNMOSD in our clinic, 168 females and 12 males tested positive for AQP4-IgG, while 15 females and one male tested negative. In our clinic, childbearing age was defined as between 18 and 45 years. Within a subset of 56 females of childbearing age, 53 were AQP4-IgG positive, and three were negative. All three who met the criteria for AQP4-negative NMOSD were also MOG-Ab negative. Of these 56 females, nine had a history of at least one pregnancy; however, only eight patients, with a total of 10 pregnancies, had sufficient recorded data available in hospital files (Fig. 1). Among these eight women, two had two pregnancies included in the study, with a one-year interval for one patient and a two-year interval for the other. The chronological details of relapses, clinical types, and treatments for individual patients are provided in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

All eight patients were AQP4-IgG positive NMOSD cases, with a mean age at disease onset of 24.38 years (SD ± 5.24) and a mean age at conception of 30.25 years (SD ± 4.13) (Table 1). At disease onset, 37.5% presented with optic neuritis (ON), 25% with transverse myelitis (TM), 12.5% with simultaneous ON and TM, and 25% with multifocal involvement beyond ON and TM. Throughout the disease course, spinal cord involvement was the most frequent clinical type (87.5%), followed by ocular involvement (62.5%) and brainstem (25%) and cerebral involvement (25%), respectively. The mean disease duration from onset to pregnancy was 5.65 years (SD ± 2.60). Additionally, seven patients (87.5%) had pre-existing comorbidities. All patients received standard prenatal supplements, including folic acid, ferrous fumarate, vitamin B6, calcium, and vitamin D. Detailed information on treatments and comorbidities for individual patients is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

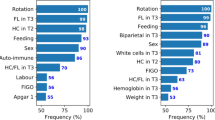

Potential influence of pregnancy on disease outcomes

We observed that five out of 10 pregnancies (50%) among our 8 pwNMOSD experienced a total of 13 relapses during the study period. TM was the most common clinical presentation, accounting for 69.23% (9/13) of relapses, followed by ON at 15.38% (2/13), ON with TM at 7.69% (1/13), and combined spinal cord [SC], brainstem [BS], and cerebellum [CB] at 7.69% (1/13) (Fig. 2). Details on the number and clinical types of relapses for each patient are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Detail of the 13 relapses of the 10 pregnancies among our 8 patients with NMOSD during the 12 months before pregnancy, pregnancy terms, and 12 months postpartum periods. Abbreviation: BP1, 12 − 9 months before pregnancy; BP2, 9 − 6 months before pregnancy; BP3, 6 − 3 months before pregnancy; BP4, 3 − 0 months before pregnancy; BS, brainstem; CB, cerebellum; DP1, first trimester; DP2, second trimester; DP3, third trimester; Mo, month; ON, optic neuritis; PP1, 0–3 months postpartum; PP2, 3–6 months postpartum; PP3, 6–9 months postpartum; PP4, 9–12 months postpartum; SC, spinal cord; TM, transverse myelitis.

In terms of timing, two relapses (15.38%; 2/13) occurred within the 12 months before pregnancy (specifically in BP2), one (7.69%; 1/13) occurred during pregnancy (specifically in the second trimester, DP2), and the remaining ten (76.92%; 10/13) occurred during the postpartum period (PP) (Fig. 2). Among these postpartum relapses, 30% (3/10) occurred within the first three months postpartum (PP1), 20% (2/10) between 3 and 6 months postpartum (PP2), 30% (3/10) between 6 and 9 months postpartum (PP3), and 20% (2/10) between 9 and 12 months postpartum (PP4).

Regarding relapse frequency, the mean annualized relapse rate (ARR) peaked at 1.2 (SD ± 1.93) during the first postpartum period (PP1) and remained elevated during PP3 (Fig. 3). However, comparisons of the mean ARR across each three-month period revealed no statistically significant differences. The mean ARR increased from 0.2 (SD ± 0.42) in the 12 months before pregnancy (BP) and 0.13 (SD ± 0.42) during pregnancy (DP) to 1.00 (SD ± 1.49) during the postpartum period (PP). Comparisons of the mean ARR between BP and DP, as well as BP and PP, did not show significant differences (BP vs. DP: Z = 0.074, p = 0.9407; BP vs. PP: Z = -1.489, p = 0.1366). However, a significant difference was observed between the mean ARR of DP and PP (Z = -1.983, p = 0.0474).

The mean annualized relapse rate at 12 months before pregnancy to 12 months postpartum. Abbreviation: BP1, 12-9 month before pregnancy; BP2, 9-6 months before pregnancy; BP3, 6-3 months before pregnancy; BP4. 3-0 months before pregnancy; DP1, first trimester of pregnancy; DP2, second trimester of pregnancy; DP3, third trimesters of pregnancy; PP1, 0-3 months postpartum; PP2, 3-6 months postpartum; PP3, 6-9 months postpartum; PP4, 9-12 months; Mo, month. Error bars represent 2 SD values above and below the mean ARR.

All five patients who experienced relapses had a history of multiple relapses throughout their disease course. Notably, patient 4, who had one relapse during BP2 and another during DP2, went on to have four consecutive postpartum relapses (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). MRI images showing prominent lesions in patients with relapses (Patients 4, 5, and 7) are presented in Fig. 4.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging findings in this study. The first row displays the MRI of patient 4: (A-B) Axial brain MRI shows multiple abnormal T2 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) hyperintense lesions at the subcortical white matter of the left temporal lobe, frontoparietal, right occipital, frontoparietal, and parietal lobe, and (C) Sagittal T2-weighted (T2W) MRI of the entire spine reveals a confluent long segment of abnormal hypersignal intensity along the cervical and thoracic vertebral levels. Spinal MRI of patient 5 is depicted in (D-E, G), showing multiple short segments of hypersignal intensity lesions on T2W along the lower C2-T7 level with faint enhancing foci at the ventral aspect at upper T3 levels (red and yellow arrows). (F) Coronal orbital MRI of patient 5 also reveals increased signal intensity on T2W (fat saturation) and gadolinium enhancement along both optic nerves from intraconal to prechiasmatic parts (green arrow). (H) The 2-month post-delivery axial brain MRI of patient 7 displays a new hypersignal intensity lesion on T2 FLAIR at the left occipital lobe, with (I) gadolinium enhancement (blue arrow).

Regarding disability accrual, Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) data were available for nine pregnancies at the last follow-up before pregnancy (BP) and for ten pregnancies at delivery and six months postpartum (PP). The mean EDSS increased from 1.56 (SD ± 2.18; range 0–6) at BP, to 1.85 (SD ± 2.31; range 0-6.5) at delivery, and further to 2.1 (SD ± 2.63; range 0-6.5) at six months PP (Fig. 5). No statistically significant differences were observed between the mean EDSS scores at each period (BP vs. Delivery: Z=-1.725, p-value = 0.0845; BP vs. 6-moPP: Z=-1, p-value = 0.3173; Delivery vs. 6-moPP: Z = 0.386, p-value = 0.6996).

All eight patients received at least one maintenance immunosuppressive (IS) therapy for NMOSD before pregnancy: all received azathioprine (AZA); six received prednisolone; three received mycophenolate mofetil (MMF); and one received rituximab (RTX) (Supplementary Fig. 1). IS therapy was discontinued during the first trimester (DP1) in 40% of pregnancies and by the third trimester (BP3) in 20% of pregnancies. Two patients switched to prednisolone and continued it throughout pregnancy. IS therapy was restarted during the postpartum period (PP) in 50% (5/10) of pregnancies, with 80% due to relapses and one patient (20%) continuing maintenance IS (third cycle of RTX). Detailed information on the timing and duration of treatments for individual patients is provided in Supplementary Fig. 1 and Table 1.

Potential influence of NMOSD on pregnancy outcomes

Maternal data were available for six pregnancies managed and delivered at our hospital. Among these, three pregnancies (50%) had labor-related complications: one case of false labor, one case of premature rupture of membranes (PROM), and one case of immediate postpartum haemorrhage. Additionally, four deliveries (66.67%) required episiotomies. None of the patients experienced pre-eclampsia or eclampsia. Detailed descriptions of pregnancy outcomes for individual patients are provided in Supplementary Table 3.

Data on fetal status were available for nine pregnancies, with four cases (44.44%) experiencing fetal complications. Among the six pregnancies managed at our hospital, three experienced adverse outcomes: one case of asymmetrical intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), one preterm birth with low birth weight (BW) and rapid breathing, and one case of intrauterine fetal demise (DFIU) with low BW. The DFIU case involved a mother with a history of antiphospholipid syndrome and was attributed to placental insufficiency (including placental abruption and one loop of nuchal cord, suggesting nutrient insufficiency). Among the three deliveries outside our hospital, one resulted in miscarriage at a gestational age (GA) of four weeks. The remaining two deliveries reported healthy babies at follow-up visits. In total, six of the nine pregnancies (75%) experienced adverse maternal and/or fetal complications.

Regarding other fetal outcomes, gestational age (GA) data were available for seven fetuses, with a mean of 32.36 weeks (SD ± 12.54). Birth weight (BW) data were available for seven live births, with a mean BW of 2,591.67 g (SD ± 518.24). Apgar scores were recorded for five fetuses, with an average score of 9.20 (SD ± 0.45) at 1 min and 10 (SD = 0) at 5 min. None of the deliveries showed meconium staining in the amniotic fluid. Detailed information on individual patients and fetuses is provided in Supplementary Table 3.

Discussion

Our study on a cohort of Thai women with NMOSD revealed a significant risk of disease relapse during the postpartum period, with 76.92% of all relapses occurring within 12 months after childbirth. The mean annualized relapse rate (ARR) during the 12-month postpartum period was significantly higher compared to the mean ARR observed during pregnancy. This finding aligns with previous studies that consistently report a peak in ARR during the first postpartum period (PP1)8,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Although previous reports indicate that up to 30% of patients may experience their first onset of NMOSD during pregnancy, our study did not include any cases where NMOSD was first diagnosed within 12 months postpartum. Interestingly, we also observed a similar peak in ARR during PP3, suggesting ongoing disease activity later in the postpartum period. Additionally, our study confirmed an increase in mean EDSS scores from the pre-pregnancy (BP) period to delivery (DP) and further to postpartum (PP), consistent with findings from meta-analyses8. These results underscore the substantial risk of increased disease activity in women with NMOSD during and particularly after pregnancy.

Relapses occurring within the 12 months before pregnancy (BP) has been identified as a predictor of subsequent relapses during pregnancy and postpartum8,17. Additionally, older age (≥ 32 years) at conception and continuous appropriate immunosuppressive (IS) therapy during pregnancy and postpartum are independent prognostic factors associated with lower rates of pregnancy-related relapses8. However, our study revealed nuanced outcomes: two patients under 32 years old who experienced relapses during BP had differing postpartum outcomes. One patient, who discontinued IS during pregnancy, encountered four subsequent relapses in the postpartum period, while the other patient, who maintained IS throughout pregnancy and postpartum, experienced no further relapses. This underscores the potential importance of continued IS therapy, particularly for patients with high disease activity, and supports the role of age at conception as a prognostic factor (Supplementary Table 1).

These observed disease outcomes may reflect the plausible influences of pregnancy on NMOSD, potentially explained by underlying immunologic changes and their interactions with immunopathogenesis24,25. Elevated estrogen levels during pregnancy can lead to increased expression of cytidine deaminase, which enhances the switching of AQP4 IgM subtypes to IgG26 Additionally, elevated estrogen levels promote the production of B-cell activating factor and type 1 interferon (IFN), facilitating the development of self-reactive B cells27, and increase inflammation due to a shift toward Th 2 immunity induced by decreased IFN-γ production24. Estrogen also reduces apoptosis of self-reactive B cells by upregulating anti-apoptotic molecules24. Furthermore, changes in sex hormone levels during pregnancy may intensify NMOSD by influencing the glycosylation of IgG glycoproteins25,28.

Our study revealed a high incidence (75%) of maternal and/or fetal complications, even among patients who experienced no relapses in the 12 months before pregnancy. Labor-related complications occurred in 50% of pregnancies, and adverse fetal outcomes were observed in 44.44% of cases. These findings highlight the elevated risks associated with pregnancy in women with NMOSD, presenting significant challenges and complications for both mothers and newborns.

The immunopathogenesis underlying NMOSD during pregnancy may provide valuable context for understanding the high rate of pregnancy complications observed in our study. Increased inflammation during pregnancy is associated with a rise in T-helper 17 (Th17) cells and a decrease in T-regulatory cells24,25. An excess of Th17 cells in peripheral blood and decidua, along with a deficiency of T-regulatory cells, has been linked to an increased rate of unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion in NMOSD25,29,30 This inflammation can be further exacerbated by enhanced Th2-mediated immunity, facilitated by elevated levels of CD56 regulatory natural killer cell24,25. Additionally, placental trophoblasts expressing the AQP4 antigen may bind to AQP4-IgG in maternal blood, leading to complement activation, deposition, and subsequent placental necrosis20,24.

While the impact of comorbidities on NMOSD relapse rates remains inconclusive, 87.5% of our patients presented with significant comorbidities. Although more patients with comorbidities experienced relapses after immunotherapy compared to those without, no correlations were found between the number of complications and disability scores or relapse rates31. Nevertheless, aside from the underlying pathophysiology of NMOSD, the comorbidities in our patients may have contributed to the adverse pregnancy outcomes observed. Moreover, oral glucocorticoids, particularly prednisone (PRE), have been associated with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) irrespective of maternal disease status32. However, there is insufficient evidence to suggest that corticosteroid use during pregnancy independently increases the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight (BW), or preeclampsia33,34.

In Thailand, AZA, MMF, and RTX are commonly prescribed medications for NMOSD. MMF, methotrexate, and mitoxantrone are contraindicated in pregnant women due to potential risks, while AZA and steroids are generally considered safer options that may be continued based on disease severity. RTX has previously been associated with potential risks of preterm delivery and fetal exposure due to its B-cell depletion effects, which vary depending on the extent of fetal exposure to the medication35,36. However, recent findings suggest that unless RTX exposure occurs during the second or third trimester, when placental transfer can lead to CD19 + B-cell depletion, its use prior to pregnancy is unlikely to significantly impact neonatal B-cell levels and is generally considered safe37. Nonetheless, RTX use may still be associated with an increased risk of miscarriage and prematurity in pregnant women with autoimmune diseases38,39.

Interestingly, one of our patients discontinued her second cycle of RTX approximately 12 weeks before her last menstrual period, corresponding to conception. Despite experiencing no relapses during the 12 months BP and DPs, she had a stillbirth attributed to placental insufficiency. In a pregnant animal model, placental insufficiency was induced by AQP4 antibody and was associated with reduced regulatory complement levels in the placenta24. However, its role in AQP4-IgG pathogenicity in NMOSD remains inconclusive24. Other factors may also have contributed to this outcome, including the mother’s existing autoimmune idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), antiphospholipid syndrome40, AQP4-IgG positivity, and complement-induced placentitis20.

Our insights into the plausible interconnected influences between pregnancy and NMOSD highlight the importance of pre-pregnancy planning and contraceptive use in managing pwNMOSD of child-bearing age. Early pregnancy planning and counseling should begin soon after an NMOSD diagnosis to help minimize pregnancy-related risks41,42 During consultations, it is crucial for physicians to emphasize the significant risks associated with pregnancy in pwNMOSD and to incorporate family planning discussions into regular visits. We advise patients to aim for at least 12 months of disease inactivity before conception, as this period is associated with lower pregnancy-related relapse rates8.

As soon as pwNMOSD becomes aware of their pregnancy, we strongly recommend early obstetrical consultation to ensure they receive antenatal care tailored to their condition. when managing pregnant pwNMOSD, the potential benefits and risks of medications must be carefully weighed. Based on our findings, AZA and RTX appear to be the most suitable options for continuing therapy during pregnancy in patients with active disease. Individualized treatment plans, including close monitoring and consideration of each patient’s disease severity and treatment history21, are essential to achieving the best possible outcomes for both mother and baby. Through these proactive approaches, we can work closely with patients to optimize their health before conception, provide comprehensive management throughout pregnancy, and potentially reduce the likelihood of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes during pregnancy and postpartum.

While our study provided a careful and detailed analysis, the small sample size resulted in low statistical power, as reflected in the lack of statistical significance in our findings, which limits the generalizability of the results. Additionally, the retrospective design, data unavailability, and missing information may affect the reliability of the study outcomes. Relying on patient-reported data introduces potential inaccuracies, and the absence of placental AQP4 immunoreactivity staining and AQP4-IgG titer measurements further restricts the accuracy of our assessments.

Prospective, multi-center studies with larger sample sizes are needed to address these limitations and clarify unresolved areas. Analyzing delivery methods and anesthetic agents—particularly spinal anesthesia agents like bupivacaine, could offer further insights into their interactions with NMOSD during pregnancy. Therefore, future research should focus on designing robust data collection methods for these specific variables. Incorporating novel biomarkers, such as glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and neurofilament light chain (NFL), for monitoring disease activity preconception and during pregnancy in pwNMOSD would also be beneficial. Additional investigation into other predictive factors for pregnancy-related relapses, including age at conception, medication continuation during pregnancy, and potential racial differences in disease and pregnancy outcomes, is warranted. Testing infants for AQP4-IgG could provide valuable insights into potential neonatal NMOSD. Such studies would support more individualized management decisions, including whether to continue or reinitiate immunotherapy, enabling a more personalized approach to patient care.

Conclusion

Thai pwNMOSD of childbearing age face substantial risks of pregnancy-related relapses and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Effective management requires regular discussions on pregnancy, planning, and contraception during preconception, along with early obstetrical consultation and closely monitored treatment plans during pregnancy and postpartum. This approach enables a more timely and individualized strategy for patient care. Additionally, GFAP and NFL may serve as useful biomarkers for monitoring disease activity preconception and during pregnancy.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings are available upon request from the corresponding authors.

References

Lennon, V. A. et al. A serum autoantibody marker of neuromyelitis optica: Distinction from multiple sclerosis. Lancet 364, 2106–2112 (2004).

Wingerchuk, D. M. et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Neurology 85, 177–189 (2015).

Contentti, E. C. et al. Application of the 2015 diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders in a cohort of latin American patients. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 20, 109–114 (2018).

Holroyd, K. B., Manzano, G. S. & Levy, M. Update on neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 31, 462–468 (2020).

Borisow, N. et al. Influence of female sex and fertile age on neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Multiple Scler. J. 23, 1092–1103 (2017).

Pandit, L. et al. Demographic and clinical features of neuromyelitis optica: A review. Multiple Scler. J. 21, 845–853 (2015).

Tisavipat, N. et al. The epidemiology and burden of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, multiple sclerosis, and MOG antibody-associated disease in a province in Thailand: A population-based study. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 70, 104511 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. Analysis of pregnancy-related attacks in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open. 5, e2225438–e2225438 (2022).

Mao-Draayer, Y. et al. Neuromyelitis Optica spectrum disorders and pregnancy: Therapeutic considerations. Nat. Reviews Neurol. 16, 154–170 (2020).

Bourre, B. et al. Neuromyelitis optica and pregnancy. Neurology 78, 875–879 (2012).

Klawiter, E. C. et al. High risk of postpartum relapses in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Neurology 89, 2238–2244 (2017).

Kim, W. et al. Influence of pregnancy on neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Neurology 78, 1264–1267 (2012).

Fragoso, Y. D. et al. Neuromyelitis optica and pregnancy. J. Neurol. 260, 2614–2619 (2013).

Huang, Y. et al. Pregnancy in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: A multicenter study from South China. J. Neurol. Sci. 372, 152–156 (2017).

Tong, Y. et al. Influences of pregnancy on neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders and multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 25, 61–65 (2018).

Shimizu, Y. et al. Pregnancy-related relapse risk factors in women with anti-AQP4 antibody positivity and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Mult. Scler. J. 22, 1413–1420 (2016).

Wang, L. et al. Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: Pregnancy-related attack and predictive risk factors. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 92, 53–61 (2021).

Reuß, R. et al. A woman with acute myelopathy in pregnancy: Case outcome. BMJ 339 (2009).

Nour, M. M. et al. Pregnancy outcomes in aquaporin-4–positive neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Neurology 86, 79–87 (2016).

Saadoun, S. et al. Neuromyelitis optica IgG causes placental inflammation and fetal death. J. Immunol. 191, 2999–3005 (2013).

Igel, C. et al. Neuromyelitis optica in pregnancy complicated by posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, eclampsia and fetal death. J. Clin. Med. Res. 7, 193 (2015).

D’Souza, R. et al. Pregnancy and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder–reciprocal effects and practical recommendations: A systematic review. Front. Neurol. 11, 544434 (2020).

Akaishi, T., Ishii, T., Aoki, M. & Nakashima, I. Calculating and comparing the annualized relapse rate and estimating the confidence interval in relapsing neurological diseases. Front. Neurol. 13, 875456 (2022).

Davoudi, V., Keyhanian, K., Bove, R. M. & Chitnis, T. Immunology of neuromyelitis optica during pregnancy. Neurol.-Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 3 (2016).

Shosha, E., Pittock, S. J., Flanagan, E. & Weinshenker, B. G. Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders and pregnancy: Interactions and management. Mult. Scler. J. 23, 1808–1817 (2017).

Pauklin, S., Sernández, I. V., Bachmann, G., Ramiro, A. R. & Petersen-Mahrt, S. K. Estrogen directly activates AID transcription and function. J. Exp. Med. 206, 99–111 (2009).

Panchanathan, R. & Choubey, D. Murine BAFF expression is up-regulated by estrogen and interferons: Implications for sex bias in the development of autoimmunity. Mol. Immunol. 53, 15–23 (2013).

Tradtrantip, L., Ratelade, J., Zhang, H. & Verkman, A. Enzymatic deglycosylation converts pathogenic neuromyelitis optica anti–aquaporin-4 immunoglobulin G into therapeutic antibody. Ann. Neurol. 73, 77–85 (2013).

Saito, S., Nakashima, A., Shima, T. & Ito, M. Th1/Th2/Th17 and regulatory T-cell paradigm in pregnancy. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 63, 601–610 (2010).

Wang, W. J. et al. Increased prevalence of T helper 17 (Th17) cells in peripheral blood and decidua in unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion patients. J. Reprod. Immunol. 84, 164–170 (2010).

Cai, L. et al. Non-immune system comorbidity in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. J. Clin. Neurosci. 107, 16–22 (2023).

Reinisch, J. M., Simon, N. G., Karow, W. G. & Gandelman, R. Prenatal exposure to prednisone in humans and animals retards intrauterine growth. Science 202, 436–438 (1978).

Bandoli, G., Palmsten, K., Smith, C. J. F. & Chambers, C. D. A review of systemic corticosteroid use in pregnancy and the risk of select pregnancy and birth outcomes. Rheumatic Disease Clin. 43, 489–502 (2017).

Shiozaki, A. et al. Multiple pregnancy, short cervix, part-time worker, steroid use, low educational level and male fetus are risk factors for preterm birth in Japan: A multicenter, prospective study. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Res. 40, 53–61 (2014).

Das, G. et al. Rituximab before and during pregnancy: a systematic review, and a case series in MS and NMOSD. Neurol.-Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 5 (2018).

Chakravarty, E. F., Murray, E. R., Kelman, A. & Farmer, P. Pregnancy outcomes after maternal exposure to Rituximab. Blood J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 117, 1499–1506 (2011).

Schwake, C. et al. Neonatal B-cell levels and infant health in newborns potentially exposed to anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies during pregnancy or lactation. Neurology: Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflammation. 11, e200264 (2024).

Garcıa-Enguıdanos, A., Calle, M. E., Valero, J., Luna, S. & Domınguez-Rojas, V. Risk factors in miscarriage: A review. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 102, 111–119 (2002).

Muglia, L. J. & Katz, M. The enigma of spontaneous preterm birth. N. Engl. J. Med. 362, 529–535 (2010).

Jin, J. et al. Thrombocytopenia in the first trimester predicts adverse pregnancy outcomes in obstetric antiphospholipid syndrome. Front. Immunol. 13, 971005 (2022).

Vukusic, S. et al. Pregnancy and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders: 2022 recommendations from the French multiple sclerosis society. Mult. Scler. J. 29, 37–51 (2023).

Kümpfel, T. et al. Update on the diagnosis and treatment of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD)–revised recommendations of the Neuromyelitis Optica Study Group (NEMOS). Part II: Attack therapy and long-term management. J. Neurol. 271, 141–176 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms Onpawee Sangsai for her assistance with patient data collection and administrative tasks and Mr Jirawit Yadee for his expert assistance on statistical analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N. B. was involved in conception and design, research operation, data collecting, analysis and interpretation of data, discussion of the results, drafting of the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and final approval of the manuscript submitted. T. O. was involved in data acquisition, interpretation of data, discussion of the results, revising it critically for important intellectual content, and final approval of the manuscript submitted. S. S. was involved in conception and design, research operation, analysis and interpretation of data, discussion of the results, drafting of the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and final approval of the manuscript submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Budtarad, N., Ongphichetmehta, T. & Siritho, S. Insights into neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder and pregnancy from a single-center study in Thailand. Sci Rep 15, 4011 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88624-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88624-x