Abstract

The advancement of the Internet of Things has positioned intelligent water demand forecasting as a critical component in the quest for sustainable water resource management. Despite the potential benefits, the inherent non-stationarity of water consumption data poses significant hurdles to the predictive accuracy of forecasting models. This study introduces a novel approach, the Robust Adaptive Optimization Decomposition (RAOD) strategy, which integrates a deep neural network to address these challenges. The RAOD strategy leverages the Complete Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (CEEMD) to preprocess the water demand series, mitigating the effects of non-stationarity and non-linearity. To further enhance the model’s robustness, an innovative optimization algorithm is incorporated within the CEEMD process to minimize the variance in multi-scale arrangement entropy among the decomposed components, thereby improving the model’s generalization capabilities. The predictive power of the proposed model is harnessed through the construction of deep neural networks that utilize the decomposed data to forecast minutely water demand. To validate the effectiveness of the RAOD strategy, real-world datasets from four distinct geographical regions are employed for multi-step ahead predictions. The experimental outcomes demonstrate that the RAOD model outperforms existing models across all considered metrics, highlighting its suitability for accurate and reliable water demand forecasting in the context of sustainable energy management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The burgeoning global population has led to a surge in urban water consumption, exacerbating the existing tension between water supply and demand. This escalating imbalance poses a formidable impediment to societal progress, particularly within the expansive water distribution networks that cater to the needs of residential and industrial sectors. Addressing this challenge is imperative for the advancement of sustainable development goals. The integration of Internet of Things (IoT) technology (Fig. 1) into smart water management systems has become a key strategy to enhance water security and operational efficiency, alleviating the complexities associated with water resource management planning1,2,3.

The essence of sustainable water management lies in the accurate forecasting of water demand and consumption, which serves as the foundation for informed decision-making in water resource planning. Applications such as leak detection and pump operation exemplify the practical utility of IoT in water management. However, the full potential of IoT platforms in water demand prediction remains largely untapped, often relying on human experts to provide estimates based on their expertise. Although valuable, this approach is insufficient for predictive analytics in real time, which is essential for the dynamic and responsive management of water resources. In this context, data-driven artificial intelligence (AI) methodologies offer a promising avenue for the precise and scientific prediction of water demand. These AI-driven approaches not only harness the wealth of data generated by IoT devices but also provide the analytical prowess necessary for the development of robust and forward-looking water supply strategies4,5,6.

As shown in Fig. 1, the IoT-enabled water distribution network combines instrumentation, interconnectivity, and intelligence to seamlessly integrate water infrastructure, culminating in a state-of-the-art smart water distribution system7,8,9,10. This advanced system facilitates a bidirectional data flow between sensors and the monitoring platform, enabling a timely and informed decision-making process. Despite these advancements, identifying patterns within the data remains the main challenge in water demand prediction, influenced by numerous factors11,12. Consequently, the extraction of inherent hidden features, crucial for reducing the impact of water demand pattern variability on hydraulic behavior and consumption within the water supply pipe network, has emerged as a critical scientific inquiry to be addressed.

An important property of water demand is the temporal variation property13,14. Many of the modern approaches exploit this property by using statistical models, machine learning models, and deep learning models15,16,17. The general methods for water demand time series modeling are autoregressive integrated moving average model (ARIMA)18 and Naïve Bayes algorithm19. However, these methods are based on linear assumptions or prior distribution selection, and their ability to extract nonlinear features is poor. Other studies propose machine learning approaches for optimizing the water demand prediction, such as Random Forest20, Support Vector Machine (SVM)21, K-nearest neighbor (KNN)22. It has gradually been recognized that due to the nonlinear nature of water demand variations, linear regression methods lack the accuracy and generalization required for practical applications. Recently, deep learning methods, such as Long Short Term Memory (LSTM)23, Graph Convolutional Recurrent Neural Network (GCRNN)8, and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU)24, have emerged as a notable and promising example of a learning algorithm in water demand modeling. These deep learning methods used for the water demand prediction can analyze high-frequency time-series signals but are limited by error accumulation during training.

To better capture the temporal characteristics and correlations of explanatory variables, researchers have concentrated on hybrid optimisation strategies25,26. Preprocessing methods such as feature selection and time-series decomposition are often used in practical problems. For example, Vo27 developed a hybrid method of convolutional neural networks and bidirectional short-term memory networks for monthly household water consumption prediction. Experimental results show that the performance of the hybrid method is better than that of traditional LSTM. Du28 combines principal component analysis with wavelet transform for data preprocessing, and uses LSTM to achieve urban daily water demand prediction. Xu29 decomposed the water demand sequences by using an integrated empirical mode decomposition method, then reconstructed it into randomness and deterministic terms through Fourier transform. Compared to other data processing methods, the decomposition algorithms can effectively improve the prediction performance of the built models through decomposing the intermittent water demand sequences into several more stationary sub-layers. However, separate optimisations and tuning for different models in a hybrid model seem to restrict the overall performance. To achieve better flexibility and robustness, optimization requires control parameters with good self-adaptive ability.

In the realm of water demand prediction models, parameter optimization has been a significant area of research focus. Several studies have explored different optimization techniques to enhance the performance of prediction models. For instance, some researchers have utilized genetic algorithms (GA) to optimize the parameters of traditional machine learning models like SVM. By evolving the parameter values over multiple generations, GA-based optimization has shown the potential to improve the accuracy of water demand forecasts30. In another approach, particle swarm optimization (PSO) has been employed to fine-tune the hyperparameters of deep learning architectures such as LSTM. PSO can effectively search the parameter space and converge towards optimal values, leading to enhanced prediction capabilities31. Additionally, ant colony optimization (ACO) has been applied in the context of water demand prediction to optimize the selection of input variables and model parameters simultaneously. This method has demonstrated its ability to handle complex relationships between variables and improve the overall model performance32. However, despite the progress made, existing parameter optimization methods still face challenges such as computational complexity and the potential for overfitting in certain scenarios. There is a need for more efficient and robust optimization strategies that can adapt to the dynamic nature of water demand data and the complexity of different prediction models.

Motivated by the quest for efficiency and sustainability, this research embarks on an exploration of hybrid optimization strategies-a critical technique in the field of intelligent water demand prediction. The crux of our study harnesses meta-heuristic optimization algorithms to refine the accuracy of hybrid predictive models, which are pivotal for the sustainable management of water resources. Our approach is validated through a series of practical experiments, designed to encompass diverse water demand scenarios. The main contributions and novelty of this paper are encapsulated within the following innovations: (1) A robust adaptive decomposition strategy is introduced to address the multifaceted nature of water demand sequences. This strategy’s dynamic parameter adjustment dismantles the rigidity of conventional fixed-mode decomposition, bolstering the model’s robustness and adaptability. (2) A objective function is crafted to gauge the complexity of prediction within decomposed sequences. By dynamically modulating decomposition parameters, this strategy enhances the model’s robustness and its capacity for generalization. 3)A novel framework for short-term water demand prediction is proposed, with experimental outcomes from varied real-world datasets underscoring its superiority and efficacy across distinct environmental and operational contexts.

This paper is organized as follows: Section “Methodologies” introduces the general framework and mathematical description of our method. We present the detailed analysis and practical experiments in Section “Experiments and discussion”, and give the evaluation results. Finally, Section “Conclusion” concludes this article.

Methodologies

The complex temporal features and strong nonlinear characteristics in water demand make it difficult to model and predict such series precisely with traditional prediction models. In this paper, we use Complementary Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (CEEMD) method to decompose time series into different components to reduce the temporal complexity. There are three core parameters that affect the performance of CEEMD: noise amplitude A, number of components K, and total lumped average times N. Heuristic optimization algorithms are very useful to find a global optima or near-optimal solution to parameter search problems. Therefore, an improved quantum genetic search algorithm is applied to obtain parameters and improve the decomposition effect efficiently.

The architecture of the proposed robust adaptive decomposition with LSTM is shown in Fig. 2. In this method, a robust adaptive decomposition strategy is proposed to decompose the original sequence into k components, and the entropy variance of multi-scale arrangement between components is computed in terms of the error function. Therefore, components with the similar complexity of temporal features can be obtained. Then, in parallel, prediction method is performed on each component. A suitable proposal prediction method is therefore the LSTM because the decomposed detailed parts of the water demand time series have stochastic characteristics and short-term dependency. This approach enables the model to focus on the temporal relationship between time segments in each component, which improves the overall prediction accuracy.

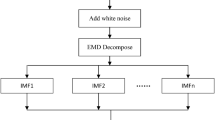

Complementary ensemble empirical mode decomposition

The Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) technique is an adaptive data analysis method that has been widely applied in non-linear and non-stationary data analysis33,34. Although the data adaptive EMD is a powerful method to decompose nonlinear signal, it has the disadvantage of the frequent emergence of mode integration. This indicates a mode mixing problem, where a single IMF either consists of signals of widely dissimilar scales, or a signal of a scale alike existing in unlike IMFs. To address this problem, a common approach is to add different Gaussian white noise with the same amplitude during each decomposition period to change the extreme point characteristics of the signal. Then, multiple EMDs are performed to obtain the corresponding IMF for overall averaging to cancel out the added white noise, which effectively suppresses the generation of mode mixing35,36. It is worth noting that paired positive and negative white noise signals should be used to minimize the signal reconstruction error, which is the basic idea of Complementary Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (CEEMD)37,38.

For water demand \(\varvec{x} = [\varvec{x}_1, \varvec{x}_2, \dots ,\varvec{x}_N]\), pairwise white noise with specific amplitudes is added to generate new sequences:

where \(\varvec{x}_{\text {pos}}^i\) is the i-th subsequence with positive noise; \(\varvec{x}_{\text{ neg }}^i\) is the i-th subsequence with negative noise; \(\varvec{n}^i\) is the white noise for the i-th subsequence; \(i=1,2,\dots ,N\), N is the total number of subsequences; A is the amplitude of white noise.

Then, the corresponding k Intrinsic Mode Function (IMF) components can be obtained by using EMD decomposition:

where \(\varvec{c}_{j}^i\) is the j-th IMF component, \(j=1,2,\dots ,k-1\); \(\varvec{\epsilon }^i\) is the residual high-frequency component.

Repeat these operations and finally the j-th component can be get by a lumped average. Thus the corresponding signal can be represented as a combination of \(k-1\) IMFs and residual:

Proposed adaptive parameter optimizer

In practical applications, time consumption in parameter optimization could be critical. It is meaningful to obtain optimal solutions with the smallest possible number of evaluations. In this study, a quantum inspired evolutionary algorithm is implemented to achieve computational efficiency. It uses a group of independent quantum bits with superposition characteristics to encode chromosomes, and updates through the quantum logic gate, so as to achieve the efficient solution of target. Unlike classical computing, the quantum inspired evolutionary algorithm has the advantage that it benefits from superposition or parallelism by considering all the paths at the same time, thus increasing its processing capacity39,40.

Chromosome representation with quantum btis

In quantum computing, the qubit is the smallest unit of the information and can be in either \(|0\rangle\) or \(|1\rangle\) states41,42,43. Then the state \(\psi\) is represented by the linear combination of ket 0 and 1.

where \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are the probability amplitude; \(|\alpha |^2\) is the probability of the quantum bit in \(|0\rangle\); \(|\beta |^2\) is the probability of the quantum bit in \(|1\rangle\). And \(|\alpha |^2 + |\beta |^2 = 1\). Hence the quantum states of two or more objects are to be described by a single chromosome. The global optimum of the chromosomes can be obtained based on the updating of the quantum revolving gate44.

where \((\alpha '_i, \beta '_i)^T\) is the probability amplitude after each update. Note that updating the quantum bit is equivalent to gradient descent, which can be written as follows:

The \(\Delta \theta\) is the change of rotation angle, the choice of which is determined by analyzing the trend of the object function at a certain chromosome. When this trend is small, \(\Delta \theta\) can be increased; when it is large, \(\Delta \theta\) can be decreased. Using this change information helps improve convergence. Then, we construct the step size function of rotation angle as follows:

where \(\Delta \theta _0\) is an initial value for \(\Delta \theta\); \(\alpha _0\),\(\beta _0\) is the optimal probability amplitude within the current population; \(\alpha _1\),\(\beta _1\) is the probability amplitude of the current solution; \(f(\varvec{X})\) is the fitness function value for an individual gene; \(\nabla f(\varvec{X}_i^j)\) is the gradient of \(f(\varvec{X})\) at the point \(X_i^j\); \(f_{\max }\), \(f_{\min }\) is the maximum and minimum values of the individual fitness function of the current population, respectively. And the gradients of \(f_{j,\max }\), \(f_{j,\min }\) are given by:

where,\(\varvec{X}_m^j\) is the j-th component of vector \(\varvec{X}_m\).

Quantum interference crossover

Basically, a genetic algorithm consists of a fixed size population of chromosomes which have the opportunity to survive in the next generation. By using genetic operators, such as selection, crossover, and mutation, the offspring can be generated for iterations. However, the crossover operator is not used in gradient-based algorithm, which often gets stuck in poor local minima.

To overcome this drawback, a quantum interference crossover is proposed as illustrated in Fig. 3. Each row represents a chromosome. And the interference crossover can be described as follows: take the 1st gene of chromosome one, 2nd gene of chromosome two, 3rd gene of chromosome three, etc. No duplicates are permitted within the same universes, if a gene is already present in the offspring, choose the next gene not already contained. Therefore, the information between each gene can be fully utilized by using quantum interference.

Improved quantum mutation

The mutation operation changes chromosomes generated by interference crossover operator45,46,47. We can select a chromosome randomly and change the probability amplitude of quantum bit arbitrarily. An example of the quantum mutation would be Hadamard-based strategy48:

Essentially the quantum mutation problem can be reduced to one strategy of rotation angle in the quantum bits. Note that it is usually hard to find the global optimum, and we may be stuck in a local optimum49. In practice, using multiple random restarts can increase out chance of finding a “good” local optimum. Of course, careful initialization can help a lot, too. However, those methods of randomness might oscillate, and convergence is not guaranteed. Here we introduce the cataclysm mechanism50. Firstly, an elite retention strategy is adopted to retain the optimal individuals, ensuring the convergence of subsequent population evolution. Then, reinitialize new individuals to replace those with poor fitness rankings in the population, thereby increasing the diversity and search range of the population. This mechanism enables the algorithm to jump out of the local optima and improve the convergence and effectiveness of the results.

Objective function improvement

For general optimization problems, the fitness function usually uses the root mean square error function (RMSE) to measure the difference between the reconstruction sequence and the original sequence. The CEEMD method eliminates residual noise by adding paired positive and negative white noise, making the RMSE of its decomposition result equal to 0. Thus, ordinary fitness functions cannot achieve the desired results.

We know that the degree of complexity and regularity can be described by multi-scale permutation entropy which is capable of fully reflecting the dynamical characteristics of sequences across different temporal scales. As a measure of the complexity or the regularity of a sequence, a large value of entropy often describes the sequence with serious nonlinear dynamics. The stronger the nonlinearity of a sequence, the higher its uncertainty and complexity, which results in further difficulty in prediction.

It is clear from the literature review in Introduction that signal decomposition technology helps to increase the precision of water demand prediction. The components with low-entropy will have good regularity and are relatively easy to predict. We therefore consider a new objective function called multi-scale arrangement entropy variance between components. By minimizing the objective function, we could obtain a sequence of components with similar nonlinear complexity, therefore limiting the nonlinear complexity of high-frequency components, and achieving better prediction results. The formula for calculating the multi-scale permutation entropy variance between components is as follows:

where \(P_i\) is the probability of symbol sequence occurrence for reconstructed components. \(H_p^s\) is the multi-scale arrangement entropy value of the s-th subsequence. The range of \(H_p\) is 0-1, which represents the randomness and complexity.

Robust adaptive optimization decomposition with long short-term memory model

For water demand data, we are interested in modelling quantities that are believed to be periodic over 24 hours or over a week cycle. Therefore, in this research, the training process is computed over a sliding window51.

Consider a set of observations \(X(t)=\left[ x_1, x_2 \ldots x_T\right]\) of the water demand. It can be divided into two parts, the input part \(X_{\text {in}}(t)=\left[ x_1, x_2 \ldots x_{T-1}\right]\) and the actual target value \(X_{\text {truth}}^{1}(t)=x_T\), in which the truth corresponds to \(X_{\text {truth}}^{1}(t)\). For a given input part, we can perform the improved signal decomposition method, and then get k subsequences:

where \(X_{\text {sub}}^s\) is the s-th subsequence. Then, the presence of a parallel processing architecture will be integrated into the LSTM to facilitate feature extraction for each IMF and increase prediction accuracy.

where F(X) is the mapping relationship learned by LSTM; \(Y_{s u b}^s\) is the prediction result of the s-th subsequence, and Y is the final prediction result.

After the decomposition step, we can compute the prediction for each subsequence. In general, a latent variable model, which can capture correlation between the visible variables via a set of latent common causes, can be applied for prediction efficiently. However, long-term information preservation and short-term input loss for latent variable models is fraught with difficulties. In this approach, LSTM is used to model these long and short-term dynamics. As shown in Fig. 4, individual LSTM units consists of an internal storage unit and three gates. The input, output, and forget operations of the memory cells are realized by multiplication of the corresponding gate. Through the gating mechanism, LSTM can maintain a certain level of gradient information to prevent gradient explosion. To alleviate the vanishing gradient problem, it properly keeps and forgets past information, indicating its great power for capturing long-term temporal dependencies. This makes possible the nonlinear learning ability for water demand time series.

Specifically, the LSTM structure is built considering the number of subsequence to be analyzed. We compute the multiplication of all the hidden state units by “sliding” this weight vector over the input. Meanwhile, all these steps can be performed in parallel on each subsequences. Then, the final output is obtained by computing the local prediction within each sliding window.

where \(Y_{{num }}\) is the predicted value of the num-th window; \(X_{\text{ truth } }^{{num }}\) is the real water demand value of the num-th window.

Experiments and discussion

In this study, water demand data is collected from a real-world water distribution system, with a sampling interval of 5 minutes52. The experimental data is chosen from different scenes, including mall, company, apartment, and school. For each scene, water demand data was continuously collected over a one-year period and aggregated into the experimental dataset, as shown in Fig. 5. We can see that, apartment water demand slightly exceeds that of malls, as apartment population flows are comparable to malls, while mall usage is limited by customer activities. In these data sets, there are various possible abnormalities in water consumption patterns53. These could include sudden spikes in water usage that deviate significantly from the typical consumption behavior of an end-user. Another possible abnormality could be an unusually low or zero consumption for an extended period, which might indicate a faulty meter or a situation where water supply has been disrupted without proper authorization. We applied the 3\(\theta\) principle to detect and handle outliers by replacing them with the average of the two adjacent values. This method preserved the original number of 8640 samples, maintaining consistent time intervals and preventing any disruption to the prediction results. Experiments are conducted on these four types of datasets, each with 105120 samples. And 30 days (8640 points) of samples are randomly selected from each dataset. The selected data is divided into an 8:1:1 split. Specifically, the first 80% of the data (the 1st to 6912th samples) is used for training the model, the middle 10% (the 6913th to 7776th samples) is used for validation, and the final 10% (the 7777th to 8640th samples) is used to test the model’s predictive performance. During training process, the sliding window of size 577 is used, which includes two-day samples (576 points) and one-step prediction values.

Three commonly-used metrics are used to evaluate the model in this study: Mean Squared Error(RMSE), Mean Absolute Error(MAE), and Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency coefficient(NSE). RMSE and MAE reflect the error between the predicted values and the actual values. NSE is used to evaluate the fitting effect and stability of the model. A value closer to 1 indicates higher stability of the model.

Model performance on IMFs

In the proposed ROADLSTM model, CEEMD is applied to decompose the original water demand sequence into several independent IMFs. Different signals have different frequency components, amplitude variations and nonlinear characteristics. The traditional IMF decomposition method with fixed parameters may not be able to handle various types of signals effectively. For example, for some signals containing abrupt change information or multi-scale frequency mixtures, the decomposition with fixed parameters may lead to the phenomenon of mode mixing, that is, components of different frequencies are wrongly decomposed into the same IMF or components of the same frequency are decomposed into different IMFs, thus affecting the accurate analysis of signal characteristics in the subsequent steps. However, the adaptive IMF decomposition can dynamically adjust the key parameters in the decomposition process, such as the number of sifting iterations and the stopping criteria, according to the specific conditions of the signals, so as to improve the accuracy and effectiveness of the decomposition. Through a robust adaptive optimization decomposition strategy, the number of IMFs can be adaptively adjusted according to data characteristics, avoiding the accumulation of estimation errors caused by excessive IMFs. Taking the mall dataset as an example, Fig. 6 illustrates the decomposition and prediction results for the mall dataset. It can be observed that the component sequences constrained by the robust optimization adaptive decomposition strategy exhibit similar nonlinear complexity. Based on this, predicting it can better learn the evolution pattern of the sequence, thereby generating more accurate prediction results.

Comparative study

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed ROADLSTM algorithm, we compare our model with eight models, including classic models like ARIMA, basic RNN, LSTM models, and hybrid models based on EMD and EEMD. Hybrid models based on EMD and EEMD specifically involve replacing CEEMD in the robust adaptive optimization decomposition strategy with EMD and EEMD. Additionally, the predictors support interchangeable use of both ARIMA and LSTM models. Note that ROADLSTM1 and ROADLSTM2 correspond to EMD and EEMD based LSTM model, while ROADAR-1 and ROADAR-2 correspond to EMD and EEMD based ARIMA model. The LSTM hyperparameter settings used in this article are shown in Table 1.

One-step prediction

Table 2 lists the performance of the above 9 models on the four types of datasets. It can be observed that basic models (LSTM, RNN, and ARIMA) yield averages of RMSE and MAE by 0.6551, 0.8203, and 0.5851, 0.7364 on the Mall and Apartment datasets, respectively. However, the RMSE and MAE rise to 1.2222, 3.7552, and 0.8912, 3.4696 on the Company and School datasets, which demonstrates the poor prediction of the nonlinear datasets. It is worth noting that there are bad prediction results on RNN. The problem with RNN is that it is very prone to overfitting, especially if the noise is high. This is because we usually initialize from small random weights, so the model is initially simple (since the tanh function is nearly linear near the origin). As training progresses, the weights become larger, and the model becomes nonlinear. Eventually it will overfit.

Utilizing the decomposition to reduce the non-stationary and non-linear characteristics in water demand data helps to obtain a sufficient prediction accuracy. From Table 2 and Fig. 7, it can be obviously found that the hybrid model can improve the performance of the LSTM model. It is shown that, compared with the single LSTM model, the LSTM-based hybrid models, consisting of ROADLSTM1, ROADLSTM2, and ROADLSTM, demonstrate reduced RMSE and MAE averages across four datasets. Specifically, for RMSE, the LSTM-based hybrid models’ averages achieve decreases of 0.1780, 0.6377, 0.2472, and 0.3989 on the Mall, Company, Apartment, and School datasets, respectively. Similarly, for MAE, the LSTM-based hybrid models’ averages achieve decreases of 0.1078, 0.2675, 0.1193, and 0.2731 on the Mall, Company, Apartment, and School datasets, respectively.

However, when employing the ARIMA prediction, the hybrid models suffer from degradation in accuracy. As shown in Table 2, the error metric scores of the ARIMA-based hybrid models, including ROADAR-1, ROADAR-2, and ROADARIMA, exhibit significant upward trends. Specifically, for RMSE, the averages of the ARIMA-based hybrid models rise to 1.7045, 2.1833, 2.2335, and 10.3483 for the Mall, Company, Apartment, and School datasets, respectively. Similarly, the averages of MAE increase to 1.3763, 1.9939, 2.0434, and 9.8374 across the same datasets. This is because as a Gaussian process model, it is difficult for ARIMA to work with high frequency nonlinear datasets. When performing decomposition on water demand datasets, the majority of the noise is added to the residual part. Therefore, the ROADARIMA and its variants show a cliff-like decline compared to traditional ARIMA.

From Fig. 7, we can see that the ROADLSTM has the lowest error score bar within the experiments. As shown in Fig. 8, the proposed ROADLSTM is closer to the true value in the fitting degree of the predicted results, which demonstrates the ability of the ROADLSTM to model periodic variables flexibly. There are significant improvements compared to suboptimal models with the average RMSE of 81.60%, MAE of 78.03%, and NSE of 1.24%. Even when the data set is seriously nonlinear, the ROADLSTM is found in practice could maintain the robust property. Regarding to the variants of ROADLSTM (ROADLSTM1 and ROADLSTM2), the proposed ROADLSTM optimizes the decomposition process by introducing additional cancellation of noise residues, thus obtaining a significant further improvement in processing seasonal and trend sequences.

Multi-step prediction

It is noted that the prediction results of decomposition based models have superior performance, with a reduction in the statistical metrics when compared with the respective models alone. Therefore, in this section, we investigated the results from the LSTM based hybrid models, applied as prediction models to perform multi-step ahead prediction. The values of RMSE, MAE and NSE of the proposed and comparison models are presented in Table 3, where the smallest value of each row is marked in boldface type. As is shown in Table 3, combining with the CEEMD, the proposed model achieves the best performance compared with other models. This conclusion can be further verified by the results presented in Fig. 9, which provides the prediction performances of the proposed and other comparison models over horizons of 1-step to 7-step ahead.

Figure 9 illustrates that ROADLSTM produces better error metric results between 1 and 4-step-ahead for all statistic metrics compared to other models. And it is obvious that the performance of comparison models on school and company decrease rapidly as the step increases. Note that this degenerate case is common to all of the prediction models between 4 and 7-step-ahead. This degradation occurs because, in the multi-step prediction process, we use the first-step prediction result as the true value to input into the model to obtain the subsequent two-step predictions. In this process, the prediction error from the first step acts as noise and is introduced, which significantly challenges the model’s robustness and accuracy. When the introduced error exceeds the model’s tolerance, the accuracy of the model experiences a sharp decline. It can, however, be shown that the statistic metrics of the ROADLSTM will not exceed the expected error, and in practice the proposed adaptive decomposition method could avoid to become rapidly unwieldy and of limited practical utility.

Ablation studies

To better understand the contribution of the improved components to the overall model, the ablation studies are conducted, aiming at investigating: (1) the forecasting performance of the variants of ROADLSTM; (2) the validity of time series decomposition to the model; (3)the impact of parameter search methods on the variants of ROADLSTM; (4) the validity of the target function modification of the parameter search method.

Variants of ROADLSTM

To verify the validity of the model, we performed ablation experiments on school dataset with relatively large errors. The traditional LSTM is chosen as the baseline model. And the random initialization method is used to select the parameters of the decomposition module to form the ROADLSTM3 model. For ROADLSTM4, we use RMSE, which measures the error of the reconstruction sequence, as the objective function of the search method to evaluate the decomposition results and select the parameters of the decomposition module. Finally, we use multi-scale permutation entropy to form ROADLSTM.

Result analysis

Table 4 summarizes the performance of the variants of ROADLSTM on the school dataset. In general, ROADLSTM has shown the best results than other models, which verifies the effectiveness of this general framework on water demand forecasting. Specifically, the predictive performance of ROADLSTM3 outperformed the baseline model by 21.92%. This proves that the decomposed sequences with few nonlinear features can achieve higher prediction accuracy than original sequences. Compared with the ROADLSTM3, RoadLSTM4 applies the parameter search method to the decomposition method, but with no obvious differences on the precision. This may be due to the fact that the paired white noise of CEEMD is completely eliminated and the reconstruction error of the decomposition sequence is always 0. In this case, ROADLSTM using MPEV as the objective function improved its predicted performance by 59.46% compared to ROADLSTM4. This means that the metric RMSE for the objective function, as was used in ROADLSTM4, would be inappropriate. These experimental results verify the validity of proposed objective function in water demand prediction.

Conclusion

This paper presents a comprehensive study on a robust multi-step water demand prediction approach within the framework of smart water management, which helps to address an imperative challenge with profound long-term economic implications in the industrial sector. The research introduces an innovative methodology for water demand forecasting, leveraging an adept decomposition technique to dissect the raw water demand series into multiple Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs), thereby facilitating a more nuanced analysis and forecasting process. This strategic decomposition effectively mitigates the inherent non-stationarity and nonlinearity of water demand time series, a critical step towards enhancing the accuracy of predictions.

To ensure practical applicability, the study advances a heuristic search algorithm designed to identify optimal parameters, aligning the model with real-world operational demands. Subsequently, an LSTM-based combined prediction model is proposed, tailored to forecast each IMF’s distinct characteristics with precision. Additionally, the introduction of a novel multi-scale permutation entropy variance function serves to quantify prediction error, bolstering the model’s resilience in the face of intricate and variable scenarios.

Through rigorous experimentation on real-world datasets, the proposed model demonstrates superior performance over established benchmarks across key metrics, including Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE). The integration of an adaptive optimization strategy further endows the hybrid model with heightened stability and precision in multi-step predictions. This research, therefore, contributes a potent and reliable predictive tool to the arsenal of water management practices, underpinning sustainable energy initiatives by optimizing water resource allocation and consumption.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to that water demand data is considered confidential by water utilities, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Mohapatra, H., Mohanta, B. K., Nikoo, M. R., Daneshmand, M. & Gandomi, A. H. Mcdm-based routing for iot-enabled smart water distribution network. IEEE Internet Things J. 10, 4271–4280 (2023).

Ismail, S., Dawoud, D. W., Ismail, N., Marsh, R. & Alshami, A. S. Iot-based water management systems: Survey and future research direction. IEEE Access 10, 35942–35952 (2022).

Salam, A. Internet of Things in Water Management and Treatment, 273–298 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2024).

Carvalho, T. M. N. & de Assisde Souza Filho, F. Variational mode decomposition hybridized with gradient boost regression for seasonal forecast of residential water demand. Water Resources Manag. 35, 3431–3445 (2021).

Kavya, M., Mathew, A., Shekar, P. R. & Sarwesh, P. Short term water demand forecast modelling using artificial intelligence for smart water management. Sustain. Cit. Soc. 95, 104610 (2023).

Wu, D., Wang, H. & Seidu, R. Smart data driven quality prediction for urban water source management. Futur. Gener. Comput. Syst. 107, 418–432 (2020).

Du, B. et al. Interval forecasting for urban water demand using PSO optimized KDE distribution and LSTM neural networks. Appl. Soft Comput. 122, 108875 (2022).

Zanfei, A., Brentan, B. M., Menapace, A., Righetti, M. & Herrera, M. Graph convolutional recurrent neural networks for water demand forecasting. Water Resources Res.58 (2022).

Sharmeen, S. et al. An advanced boundary protection control for the smart water network using semisupervised and deep learning approaches. IEEE Internet Things J. 9, 7298–7310 (2022).

Nie, X. et al. Big data analytics and IOT in operation safety management in under water management. Comput. Commun. 154, 188–196 (2020).

Cominola, A., Giuliani, M., Piga, D., Castelletti, A. & Rizzoli, A. Benefits and challenges of using smart meters for advancing residential water demand modeling and management: A review. Environ. Model. Softw. 72, 198–214 (2015).

Xu, Z., Lv, Z., Li, J. & Shi, A. A novel approach for predicting water demand with complex patterns based on ensemble learning. Water Resour. Manage 36, 4293–4312 (2022).

Lee, D. & Derrible, S. Predicting residential water demand with machine-based statistical learning. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 146, 04019067 (2020).

Nunes Carvalho, T. M., de Souza Filho, F. D. A. & Porto, V. C. Urban water demand modeling using machine learning techniques: Case study of fortaleza, brazil. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 147, 05020026 (2021).

Cai, J. & Ye, Z.-S. Contamination source identification: A bayesian framework integrating physical and statistical models. IEEE Trans. Industr. Inf. 17, 8189–8197 (2021).

Oikonomou, K., Parvania, M. & Khatami, R. Optimal demand response scheduling for water distribution systems. IEEE Trans. Industr. Inf. 14, 5112–5122 (2018).

Harmouche, J. & Narasimhan, S. Long-term monitoring for leaks in water distribution networks using association rules mining. IEEE Trans. Industr. Inf. 16, 258–266 (2020).

Du, H., Zhao, Z. & Xue, H. Arima-m: A new model for daily water consumption prediction based on the autoregressive integrated moving average model and the markov chain error correction. Water 12, 760 (2020).

Ilić, M., Srdjević, Z. & Srdjević, B. Water quality prediction based on naïve bayes algorithm. Water Sci. Technol. 85, 1027–1039 (2022).

Chen, G., Long, T., Xiong, J. & Bai, Y. Multiple random forests modelling for urban water consumption forecasting. Water Resour. Manage 31, 4715–4729 (2017).

NajwaMohdRizal, N. et al. Comparison between regression models, support vector machine (svm), and artificial neural network (ann) in river water quality prediction. Processes 10, 1652 (2022).

Juna, A. et al. Water quality prediction using KNN imputer and multilayer perceptron. Water 14, 2592 (2022).

Kühnert, C., Gonuguntla, N. M., Krieg, H., Nowak, D. & Thomas, J. A. Application of LSTM networks for water demand prediction in optimal pump control. Water 13, 644 (2021).

Chen, L. et al. Short-term water demand forecast based on automatic feature extraction by one-dimensional convolution. J. Hydrol. 606, 127440 (2022).

Samani, S., Vadiati, M., Delkash, M. & Bonakdari, H. A hybrid wavelet-machine learning model for qanat water flow prediction. Acta Geophys. 71, 1895–1913 (2023).

Khozani, Z. S., Banadkooki, F. B., Ehteram, M., Ahmed, A. N. & El-Shafie, A. Combining autoregressive integrated moving average with long short-term memory neural network and optimisation algorithms for predicting ground water level. J. Clean. Prod. 348, 131224 (2022).

Vo, M. T., Vu, D., Nguyen, H., Bui, H. & Le, T. Predicting monthly household water consumption. In 2022 RIVF International Conference on Computing and Communication Technologies (RIVF), 726–730 (IEEE, 2022).

Du, B., Zhou, Q., Guo, J., Guo, S. & Wang, L. Deep learning with long short-term memory neural networks combining wavelet transform and principal component analysis for daily urban water demand forecasting. Expert Syst. Appl. 171, 114571 (2021).

Xu, Y., Zhang, J., Long, Z. & Chen, Y. A novel dual-scale deep belief network method for daily urban water demand forecasting. Energies 11, 1068 (2018).

Candelieri, A. et al. Tuning hyperparameters of a SVM-based water demand forecasting system through parallel global optimization. Comput. Oper. Res. 106, 202–209 (2019).

Du, B. et al. Interval forecasting for urban water demand using PSO optimized KDE distribution and LSTM neural networks. Appl. Soft Comput. 122, 108875 (2022).

Abdelaziz, R. Application of ant colony optimization in water resource management. In Andriychuk, M. & Sadollah, A. (eds.) Optimization Algorithms, chap. 6 (IntechOpen, Rijeka,) (2023).

Boudraa, A.-O. & Cexus, J.-C. EMD-based signal filtering. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 56, 2196–2202 (2007).

Rawal, K. & Ahmad, A. Mining latent patterns with multi-scale decomposition for electricity demand and price forecasting using modified deep graph convolutional neural networks. Sustainable Energy, Grids and Networks 101436 (2024).

Wu, Z. & Huang, N. E. Ensemble empirical mode decomposition: A noise-assisted data analysis method. Adv. Adapt. Data Anal. 1, 1–41 (2009).

Shi, J. & Teh, J. Load forecasting for regional integrated energy system based on complementary ensemble empirical mode decomposition and multi-model fusion. Appl. Energy 353, 122146 (2024).

Yeh, J.-R., Shieh, J.-S. & Huang, N. E. Complementary ensemble empirical mode decomposition: A novel noise enhanced data analysis method. Adv. Adapt. Data Anal. 2, 135–156 (2010).

Chen, S. & Zheng, L. Complementary ensemble empirical mode decomposition and independent recurrent neural network model for predicting air quality index. Appl. Soft Comput. 131, 109757 (2022).

Acampora, G. & Vitiello, A. Implementing evolutionary optimization on actual quantum processors. Inf. Sci. 575, 542–562 (2021).

Gupta, S. et al. Parallel quantum-inspired evolutionary algorithms for community detection in social networks. Appl. Soft Comput. 61, 331–353 (2017).

Bennett, C. H. & Divincenzo, D. P. Quantum information and computation. Nature 404, 247–255 (2000).

Williams, C. P. & Clearwater, S. H. Ultimate zero and one - computing at the quantum frontier (Ultimate zero and one–computing at the quantum frontier,) (2000).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum computation and quantum information. Math. Struct. Comput. Sci. 17, 1115–1115 (2002).

Zhang, G. Quantum-inspired evolutionary algorithms: A survey and empirical study. J. Heurs 17, 303–351 (2011).

Liu, Y. & Wang, L. Quantum-inspired evolutionary algorithm with dynamic mutation strategy for global optimization. Appl. Soft Comput. 109, 107504 (2021).

Li, Z., Zhang, Q. & Deng, Z. A novel quantum-inspired evolutionary algorithm with adaptive mutation operator for multi-objective optimization. Expert Syst. Appl. 200, 117039 (2022).

Zhang, J., Chen, Y. & Zhao, X. Enhanced quantum-inspired evolutionary algorithm with hybrid mutation strategies for complex optimization problems. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2023, 5095483 (2023).

Holland, J. H. Adaptation in Natural and Arti cial Systems : An Introductory Analysis With Applications to Biology (MIT Press, 1992).

Back, T., Hammel, U. & Schwefel, H. P. Evolutionary computation: Comments on the history and current state. IEEE Press (1997).

Wang, H., Liu, J., Zhi, J. & Fu, C. The improvement of quantum genetic algorithm and its application on function optimization. Math. Problems Eng. 2013, 321–341 (2013).

Bandara, K., Bergmeir, C. & Smyl, S. Forecasting across time series databases using recurrent neural networks on groups of similar series: A clustering approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 140, 112896 (2020).

Yang, C., Meng, J., Liu, B., Wang, Z. & Wang, K. A water demand forecasting model based on generative adversarial networks and multivariate feature fusion. Water 16, 1731 (2024).

Ghamkhar, H., Jalili Ghazizadeh, M., Mohajeri, S. H., Moslehi, I. & Yousefi-Khoshqalb, E. An unsupervised method to exploit low-resolution water meter data for detecting end-users with abnormal consumption: Employing the dbscan and time series complexity. Sustain. Cit. Soc. 94, 104516 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Zhejiang Natural Science Foundation Project (NO.LQ23F030002), ’Ling Yan’ Research and Development Project of Science and Technology Department of Zhejiang Province (NO.2023C03161,2023C03189), and the Open Research Project of the State Key Laboratory of Industrial Control Technology (NO.ICT2022B34).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.W. conceived the experiment(s), J.M. and B.L. conducted the experiment(s), K.Z. and Z.W. analysed and interpreted the data, K.W. and J.M. analysed the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

There are no competing financial or non-financial interests in relation to the work described.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, K., Meng, J., Wang, Z. et al. Robust adaptive optimization for sustainable water demand prediction in water distribution systems. Sci Rep 15, 4039 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88628-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88628-7