Abstract

This study examines the impact of monsoon systems on the isotopic composition of rainfall in India’s core monsoon zone (CMZ). The CMZ is influenced by the monsoon trough and the low-pressure systems that cause considerable rain. However, there is a lack of systematic studies on how these monsoon systems affect the isotopic composition of precipitation in the CMZ. A six-year precipitation isotopic record shows that the low-pressure systems, through their origin, trajectory, and intensity, significantly impact the isotopic values of rainfall. These systems and convective activities typically produce depleted isotopic values. An examination of the monthly composited LPS (low-pressure system) intensity and its corresponding precipitation isotopic values revealed a noteworthy inverse relation. Additionally, terrestrial evaporation could significantly impact the isotopic values of precipitation. The isotopic variabilities in central and northeastern India showed an out-of-phase distribution, mimicking the dipolar nature of rainfall variability. This characteristic feature makes the CMZ ideal for proxy analysis to reconstruct past rainfall variability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Core Monsoon Zone (CMZ), located in central India (approximately defined by an area: 18-28°N, 65-88°E1; see Fig. 1a), plays a crucial role in regulating monsoon processes. This region is characterised by prominent synoptic-scale systems such as the semi-permanent monsoon trough during the summer monsoon season. The monsoon trough is a low-pressure area that forms due to the interaction between the inter-tropical convergence zone and the cyclonic monsoon circulation. It develops during the monsoon season (June to September; henceforth defined as JJAS), when westerlies from the south and easterlies from the north converge. The point of convergence is called the ‘monsoon trough’ axis, which extends from the northwestern Indian border to the Bay of Bengal in the east. Differential heating of land and ocean surfaces and other atmospheric conditions cause the monsoon trough to oscillate north-south. When it moves north, the rainfall over the plains decreases sharply, resulting in a ‘break phase’ of monsoon2. During its normal position, the Indian plains receive good monsoon rain, known as the ‘active phase’ of the monsoon. The dynamics of the monsoon trough and its associated effects have been studied by several investigators3,4.

The monsoon trough and its influence on rainfall in India. (a) The map shows the mean sea level pressure (shading), with low-pressure areas indicating the location of the trough (thick white line). The area covered by the green line marks the core monsoon zone of India. The white dotted lines schematically illustrate the path of the low-pressure systems that form in the north Bay of Bengal and propagate to the central and western parts of India. (b) The region where the low pressure system tracks have been calculated is delineated by a box outlined with a dotted red line. Shading represents sea level pressure. The presence of an extremely severe cyclonic storm (‘Vayu’), which took place in the second week of June 2019, is depicted by the closed contours displayed near the north-western coastal area of India. Please refer to the main text for a detailed information. Figure created using Ferret software, Version: 7.63 (https://ferret.pmel.noaa.gov/Ferret/).

Active and break phases are integral components of the monsoon system and are characterised by distinct meteorological conditions. During the active phase, rainfall is typically high, and outgoing longwave radiation (OLR) and mean sea-level pressure are low. During the break phase, these conditions are reversed. Since rainfall variation across India is not coherent, it is not the all-India average rainfall, instead, rainfall over the CMZ is used to define active and break phases1. Various meteorological variables have been used to define these phases. Rajeevan et al.1 provide an objective definition based on rainfall variability: active and break phases are periods during July and August when normalised rainfall anomalies over the CMZ exceed threshold values (+ 1 and − 1 respectively) for three consecutive days. These authors also showed that rainfall across the CMZ is coherent and strongly correlates with all-India summer monsoon rainfall. Thus, the CMZ is a critical region for studying interannual rainfall variation in India.

During the monsoon season, ‘low-pressure systems’ (LPS) are significant weather phenomena primarily observed in central India and its adjoining areas. LPSs are atmospheric dynamic conditions characterised by lower atmospheric pressure than the surrounding areas with winds blowing in an anti-clockwise direction north of the equator. Monsoon LPSs can intensify into monsoon depressions and are the principal rain-bearing systems during the southwest monsoon period over India. They generate substantial rains due to the westward passage of the monsoon depressions forming in the Bay of Bengal. They, however, are not direct rain source but play a crucial role in weather patterns that can lead to precipitation.

Several investigators studied the LPS dynamics5,6,7,8; a brief description follows. LPS typically forms when warm, moist air rises, creating an area of low pressure beneath it. As the air rises, it cools and condenses, forming clouds and precipitation. Water vapours become isotopically depleted as they rise and condense into clouds and rain. Air from the surrounding higher-pressure areas moves into the low-pressure region. This air is deflected by the Coriolis effect, causing it to rotate counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere. LPS can be associated with weather systems, such as depressions and cyclones, which are significant rain producers. Estimates suggest that the LPS can contribute up to 60% of the mean JJAS seasonal rainfall over the CMZ8,9. As the name suggests, a low-pressure system is measured by the drop in sea-level pressure. Details are provided in the Methods section.

The monsoon trough acts as a guiding feature for the LPS, providing a track to move across; hence, it influences the path and development of the LPS. The interaction between the LPS and the monsoon trough can lead to variations in rainfall patterns, including extreme precipitation events in central India10.

Isotopic analysis of precipitation can provide valuable insights into monsoon processes. For example, precipitation isotopes strongly respond to the monsoon intra-seasonal oscillations11,12 and the Madden-Jullian Oscillation13. Chakraborty et al.14 demonstrated how the isotopic values of rainfall and plant transpiration could delineate the monsoon’s active and break phases. Some investigators also estimated the monsoon onset15 and withdrawal dates16 using the water isotopes in India. However, most of these studies have focused on specific regions of India: the south17,18,19, the west20,21, the east including the northeast22,23,24, and the north25,26,27,28. Isotopic analysis of precipitation and vapor during ocean expeditions over the Bay of Bengal has also been reported29,30,31.

Precipitation isotopes have been studied in the Andaman and Minicoy Islands by several investigators16,32,33,34. However, the central Indian region, especially the CMZ, has received little attention. Midhun et al.35 analysed precipitation isotopes at six stations near the CMZ and found that they were influenced by monsoon circulation. However, only one station (Bhopal: 23.25°N, 77.45°E) was prominently located within the CMZ, and the data were only for 2013, therefore unsuitable for examining inter-annual variability in response to CMZ dynamics or the variabilities associated with the low-pressure systems. Oza et al.21 reported long-term (2005–2016) precipitation isotopic data from Ahmedabad on the western edge of the CMZ and explained the progressive depletion of isotopes from early to late monsoon. Given the importance of the CMZ vis-à-vis the monsoon trough on the Indian Summer Monsoon (ISM) dynamics, examining their impact on the precipitation isotopes at a strategic location within the CMZ is essential.

Such a study is also important from a paleo-monsoon perspective. Several authors have analysed natural archives from the CMZ to study paleo-monsoon variability using speleothems36,37 and lake sediments38. Speleothem analysis from the CMZ and northeast India demonstrated a dipolar pattern of rainfall variability in these two regions on centennial timescales39. Since the isotopic signal of past rainwater is transferred to oxygen in speleothem carbonate, it is essential to establish that the isotopic values of rainfall in these two regions also show dipolar behaviour. This hypothesis can be tested using the rain isotopes from these two regions, albeit on a shorter timescale, within a season.

We report multi-year precipitation isotopic records from Sagar, the primary sample collection site at the heart of the CMZ of India. We also report precipitation isotope records from a few other locations around the CMZ: Pune, Barabanki and its two neighbouring sites, and Kolkata, which belong to the southern, northern, and eastern boundaries of the CMZ. We address the following science questions: How do the precipitation isotope records respond to the synoptic scale monsoon rainfall variability observed in the CMZ, especially in the context of active and break phases of rainfall? This issue is intricately linked to the LPS and, in turn, to the monsoon trough dynamics. Hence, a corollary of the above objective is to explore the possible association between the precipitation isotopes, the LPSs, and how the monsoon trough modulates the precipitation isotopes. Secondly, we explore if the precipitation isotopes in the central and northeast Indian regions demonstrate an out-of-phase characteristic. Lastly, we discuss the paleoclimatic implications.

Results

Figure 2 (a to f) shows the rainfall and oxygen isotopic composition at the sampling site during the monsoon season (JJAS) from 2016 to 2021. The blue bars represent the rainfall amount, and the red line represents the isotopic variation (left panel). The right panel (Fig. 2g) presents the local meteoric water line (LMWL: black dotted line). The red dots, representing specific periods in 2019, are characterized by intense surface evaporation with a slope higher than the GMWL (~ 8); the corresponding LMWL is termed as ‘red-LMWL’. The blue dots and their representative LMWL include all points except the red dots. This figure reveals that δ18O varies considerably; very low values typically correspond to heavy rainfall events. Apart from seasonal changes, the δ18O values decrease steadily from June to September, with an accelerated decline observed in recent years. The LMWL has a slope (7.78) that is slightly lower than the Global Meteoric Water Line (GMWL, slope ~ 8) but not significantly different from that of the Indian Meteoric Water Line (IMWL, slope ~ 7.93) reported by Kumar et al.40. Likewise, the intercept (6.16) is lower than the GMWL and IMWL (10 and 9.9, respectively).

Intra-seasonal variability of rainfall and its oxygen isotopic variability for the monsoon season (June to September) from 2016 to 2021(a–f) is shown in the left panel. Blue bars represent the rainfall at the sampling site, while the red line depicts the isotopic variability. The local meteoric water line (LMWL, black dotted line) is shown in the right panel (g). The red dots, representing specific periods in 2019, are characterised by intense surface evaporation with a slope higher than that of the GMWL (~ 8). The blue dots and their representative LMWL include all points except the red dots.

Low-pressure systems, outgoing long-wave radiations, and their influence on the precipitation isotopes

Figure 3 displays the interplay between precipitation patterns and isotopic changes, highlighting the inverse correlation between δ18O values (red lines) and the SPA (Standardised precipitation anomaly; blue bars). It also tracks LPS events (magenta bars), characterized by low surface air pressure and converging winds, resulting in lifting air and water vapours aloft. This phenomenon leads to strong isotopic fractionation, depleting the upper-level water vapor and subsequent rainfall in heavy isotopes, so we expect to see low isotopic values during these events. The data from 2016 to 2021 show that significant LPS events, like those in June and July 2016, coincide with high SPAs, suggesting LPS as a primary rain mechanism. These events are further illustrated by the LPS tracks (right panel; Fig. 3b, d, f, h, j and l) and their impact on isotopic depletion in rainfall.

Precipitation dynamics of the core monsoon zone and their isotopic record at Sagar. Left column (a,c,e,g,i,k). The magenta bars depict the LPS events, while the blue bars represent the standardized precipitation anomaly. The precipitation δ18O is shown by the red line, and OLR by the dotted line. Right Column (b,d,f,h,j,l). The LPS tracks during the monsoon season. Each track is labelled by a number that matches the corresponding event in the left column. The arrows on the tracks indicate the direction of LPS movement. The LPS that did not move considerably is shown by a small rectangular open box. The filled black box represents the Sagar rainwater collection site.

In July 2016 (Fig. 3a), no significant LPS events occurred despite a brief positive SPA. The isotopic records during this period showed low values during LPS events and higher values in the intervals between these events.

The weather mainly remained dry until the end of July, registering an increase in δ18O values, except for a notable drop on the 27th. In August, a major LPS event (#3) near the BOB (Bay of Bengal) coast coincided with positive SPA and low OLR, significantly affecting δ18O values in Sagar. Subsequent LPS events led to further isotopic depletions. Post-August, LPS events were rare, maintaining higher δ18O levels, with minor depletions noted in late September LPS occurrences.

The initial 2017 LPS event (Fig. 3c) was not captured in the δ18O record due to missing early samples. δ18O values stayed around 0 ± 2‰ until July, when two major LPS events (#2) led to a notable δ18O decrease, hitting − 15‰ on July 20th. A subsequent LPS event (#3) from July 23–28 saw OLR values rise, yet δ18O dropped to -11.6‰. In August and September, further LPS events (#4) linked to low OLR significantly reduced δ18O levels, with a September event (#5) causing a drop to nearly − 19‰.

In June 2018, δ18Osagar decreased during a low OLR episode (Fig. 3e). July saw two significant LPS events, leading to sharp drops in δ18O values, which lagged the LPS by days. August featured another LPS event and two additional days with positive SPA values, affecting δ18O levels despite no rainfall mid-month. Subsequently, δ18O increased slightly on 16th August. The period ended with no further LPS but continued positive SPA and a significant δ18O reduction in late August. A final LPS event in early September lowered δ18Osagar before a dry spell ensued.

The 2019 (Fig. 3g) monsoon in India was unusually strong41, leading to heavy rainfall in studied regions despite a low frequency of LPS events. The first LPS appeared in early June, with a notable event (#2) from June 12–17 linked to a very severe cyclonic storm ‘Vayu’ (see Fig. 1b). A third event from June 18–21 brought no significant rain to our site, resulting in minimal isotopic data. The δ18O levels were high and slightly decreased by the month’s end, influenced by a minor positive SPA and a drop in OLR. In early July, a sharp OLR decline correlated with a significant decrease in isotopic values without any LPS occurrence.

A monsoon break phase raised δ18O levels in mid-July, followed by an active phase with regular δ18O drops due to low OLR, reaching a significant low on August 9. Despite a brief dry spell raising δ18O levels, they fell sharply with another rainy spell and OLR drop. The short dry spells and rainy periods continued through August, with δ18O levels fluctuating. In September, low OLR and LPS events in the BOB led to low δ18O, which decreased further despite a late-month LPS event (#6) in the Arabian Sea that did not affect δ18Osagar significantly.

In June 2020 (Fig. 3i), δ18O levels were stable but dropped to -4‰ following an LPS event (#2) in early July. Subsequent LPS event (#3) had varied impacts on δ18Osagar, with a significant drop to -13‰ in August coinciding with a low OLR (caused by #4). Despite low rainfall in mid-August, δ18Osagar increased slightly, attributed to sub-cloud evaporation. A strong LPS in late August (#6) caused a record low in δ18Osagar (~ -16‰), which fluctuated with subsequent LPS activities. Contrary to general perception, this LPS event was associated with rising OLR values.

In 2021 (Fig. 3k), the BOB coast experienced two weak LPS events in June (#1 and #2), affecting δ18Osagar values minimally, with a slight increase during the second due to low rainfall. A subsequent dry spell led to higher δ18O levels until a drop on July 27, linked to low OLR. The monsoon’s active phase began, marked by a significant LPS event (#3) and low OLR, reducing δ18O values. After a brief increase, δ18O fell again, though the cause remains unclear. Late August’s fourth LPS event and September’s strongest event (#5) significantly lowered δ18O, with another LPS in late September slightly affecting it.

A detailed event-by-event description of the LPS and the associated δ18O variations for Sagar is provided in the Supplementary Information (Note: S1). An animation illustrating the synoptic processes and their influences on the precipitation isotopes is provided in an accompanying video entitled: “Monsoon processes and precipitation isotopes.”

Deuterium excess (d-excess) is crucial for understanding source moisture conditions. Its values can vary significantly based on the source. Terrestrially generated moisture often results in rainfall with higher d-excess values than rainfall from advected oceanic moisture42. The co-variations of d-excess, δ18O, and recycled rain for select years are shown in Fig. S6, and a specific case from 2019 is discussed in a later section.

Precipitation isotopes at other locations of the CMZ and the low-pressure systems

To better understand how LPS influences the oxygen isotopes of rainwater in the CMZ region, we compared the precipitation δ18O records from a few other sites within the CMZ. We used the isotopic data from Dhanbad (23.81°N, 86.44°E) and Bhopal (23.25°N, 77.45°E) from Midhun et al.35. Dhanbad is on the eastern side, and Bhopal is in the central region of CMZ. As mentioned earlier, we also selected Pune, Jaludi Nagar, and Paramanek Nagar, the sites in the southern and northern regions of the CMZ. We report the Pune data only for 2019 here. The isotopic data (only 2018) was generated from three sites, Barabanki, Paramanek Nagar and Jaludi Nagar, belonging to the northern CMZ region, which spanned for a couple of months during the monsoon season. They were used to examine the co-variability with the Sagar data. We have also used precipitation isotopic data from Darjeeling24, a site belonging to the Himalayan foothills in northeast India. The Darjeeling data have been used to check the anti-phasing characteristic of the precipitation isotopes for the CMZ and the northeast Indian region. Figure 1b shows the rainwater collection sites.

Moreover, we used the precipitation isotopic data of Kolkata, a site on the eastern edge of the CMZ. Since Kolkata is near the coastal region of the north Bay of Bengal, where most of the LPSs originate, the isotopic values in this site are likely to be strongly modulated by them. We used the data from 2016 to 2018 from Chakraborty et al.24, and the 2019 isotopic data are reported here. While we present the Bhopal and Dhanbad cases here, the description of other sites’ data, because of their repetitive nature, is provided in the Supplementary Information (Northern CMZ region: Note S2; Eastern CMZ region: Note S3).

Bhopal and Dhanbad isotopic records

Figure 4a shows the δ18O rainfall values at Dhanbad and Bhopal in 2013, and the LPS variations. The red (δ18Odhanbad) and blue (δ18Obhopal) lines indicate the oxygen isotopic rainfall values at these two cities; the light magenta-coloured bars depict the LPSs, while the dotted line shows the OLR variability. The corresponding LPS tracks are shown in Fig. 4b.

Precipitation isotope records from Dhanbad (red line) and Bhopal (blue line) are shown in the left panel (a), along with the LPS (magenta bar) and OLR (dotted line). The LPSs are labelled with numerals from 1 to 6. The corresponding tracks are displayed in the right panel (b). The red and blue dots in the map indicate the locations of Bhopal and Dhanbad. The isotopic data are sourced from Ref.35.

Figure 4a shows that δ18Obhopal was strongly affected by the first two LPS events, coinciding with sharp drops in OLR values. The first event (#1) formed in the coastal region of BOB and moved westward, causing a significant decrease in δ18Obhopal but only a slight change in δ18Odhanbad. The second event in the third week of July originated in the BOB, coincided with a sharp decline in OLR, moved north. Then, it turned northwest when associated with a drop in OLR. Although it was far from Bhopal, it reduced Bhopal’s and Dhanbad’s isotopic values. The third event (#3) occurred in the third week of August and moved from the BOB coastal region to near Bhopal. During this period, the isotopic values at both sites dropped sharply. The fourth event (#4) also lowered the isotopic values of both sites around September 19.

The isotopic records of Dhanbad and Bhopal, about 1100 km apart, decreased simultaneously for most events, but the decrease in Dhanbad was smaller for the first event. The other events (#2, #3, #4, and #6) also caused significant drops in δ18Odhanbad. Approximately synchronized reductions in the isotopic values of these two distant places confirm that the isotopic values within the core monsoon zone concurrently (± 2 days) respond to the synoptic scale processes driven by the LPSs and associated convective activities.

However, some smaller fluctuations showed different patterns. For example, δ18Odhanbad dropped around July 27, but δ18Obhopal increased. On the 26th, Bhopal recorded only 2.4 mm of rainfall, which may have caused raindrop evaporation and increased δ18O. However, on the 27th, Bhopal had over 46 mm of rainfall; despite this heavy rain, δ18O increased further. Similarly, a low δ18O event in Dhanbad around August 10 coincided with a high δ18O value in Bhopal. Statistical analysis by Midhun et al.35 identified occurrences of high and low isotopic values.

Midhun et al.35 argued that the periodic depletions in the isotopic values were due to the moisture from the BOB, while the enriched values were from the Arabian Sea. However, as explained here, the depleted values mostly coincide, but the enriched values timing did not show a consistent behaviour. The formation and movement of the LPS over the BOB could better explain the observed isotopic depletions.

Monsoon trough dynamics and the precipitation isotopes

As previously mentioned, the monsoon trough is a dynamic feature that oscillates in the north-south direction, significantly impacting the rainfall pattern over the CMZ. When the trough shifts northward, it leads to decreased rainfall, whereas when it remains positioned over this zone, rainfall intensifies. Consequently, the normal position of the trough is expected to yield low isotopic values, while its northward movement is likely to result in increased isotopic values in the CMZ.

To test this hypothesis, we conducted an empirical study. First, we measured the linear perpendicular distance from the observation site (Sagar) to the monsoon trough using daily weather charts published by the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD). Next, we converted this distance into geographical kilometres. Subsequently, we plotted a scatter plot comparing this distance with the precipitation isotopes and created a composite diagram spanning multiple years. Figure 5 visually represents our findings, revealing a positive trend indicated by the regression black line.

The scatter plot provides a visual representation of the correlation between the oxygen isotopes (δ18O) in precipitation at Sagar and its distance from the monsoon trough. The x-axis denotes the perpendicular distance, in kilometres, from Sagar to the trough. On the other hand, the y-axis displays the δ18O values of the precipitation at Sagar. The plot employs a colour scheme to differentiate between years, as specified in the accompanying legend.

Discussion

The isotopic records at Sagar and Bhopal reveal that the LPSs strongly influence the periodic drops in precipitation δ18O. Moreover, the isotopic records tend to decrease on an intra-seasonal scale. The LPSs have different intensities of cyclonic circulation, which affect the water isotopes differently. Cyclonic circulation lifts moist air from the surface to higher altitudes. Through the Rayleigh fractionation mechanism, the lifting process preferentially transports lighter isotopes upward, resulting in isotopically depleted cloud droplets.

Moreover, when these cloud droplets condense into a liquid phase, the heavier isotopes preferentially move into the condensed phase, making the remaining cloud droplets further isotopically light. Hence, the heavy rain associated with cyclonic processes usually produces isotopically depleted rainwater. However, some anomalies are observed. Not all heavy rainfall events and/or LPSs lower the isotopic values, and sometimes the isotopic values drop significantly without the LPS events.

For example, the first week of July 2016 had relatively high δ18O values despite the considerable rainfall. The reason for this is unclear, but it is noteworthy that the following LPS (event #2) caused a significant decrease in δ18O. The last week of July showed a positive SPA, but the local rainfall was only about 2 mm for two days, resulting in enriched isotopic values possibly due to raindrop evaporation. A similar situation occurred during the third week of August 2018; on the 18th, the rainfall was less than a mm, and the δ18O value increased sharply. The cause of the enrichment in the last week of July 2019 was also unclear, as the rainfall was reasonable. The isotopic values were probably more influenced by the convective activities as δ18O and OLR mostly co-varied during this time. However, none of these enrichments were associated with any LPS event. The only exception was September 20, 2019, an LPS-assisted day and had a higher isotopic value. The possible reasons are explained below. Despite good positive SPA, the isotopic values were moderately high from 25th August to 4th September (Fig. 6). Cloud microphysical processes, such as raindrop evaporation, enrich the precipitation isotopic values, resulting in an LMWL slope lower than 843,44. On the other hand, the intercept of the LMWL is influenced by kinetic fractionation not only at source45 but also by surface evaporation at the local and regional levels. For example, Welp et al.46 showed how plant transpiration could affect the d-excess values of the ambient water vapour.

Co-variation of d-excess (red line) with Recycled Ratio (RR, black line), Standardized Precipitation Anomaly (SPA, light blue bars), and δ18O (green line). Note the contrasting relationships between d-excess and RR: an inverse correlation in June-July and a strong covariance in August-September (see text for detailed explanation).

We have examined the impact of model-derived recycled ratio (RR) on d-excess values of precipitation. Figure S6 presents the line plots of δ18O, d-excess and the RR records. d-excess generally covaried with RR but deviated occasionally. A specific case is presented in Fig. 6, which shows the RR (black line) over a 4ox10° area that includes Sagar. Over the monsoon season, the behaviour of RR and d-excess varied: inversely in June and July 2019, and covarying in August and September. The shift in the RR-d-excess relationship is attributed to changes in moisture sources. During the late-phase monsoon, increased surface evaporation from terrestrial sources, which typically have higher d-excess than oceanic moisture47,48, led to significant rainfall and higher RR values. This, in turn, influenced precipitation isotopic values, resulting in covariance with d-excess and decreased δ18O. Occasional raindrop evaporation also contributed to these changes. More research is needed due to the WRF-WVT model’s lack of raindrop evaporation data.

Evidence of surface evaporation may come from the distribution of the isotopic values comprising the LMWL as explained by Putman et al.43. These authors highlighted the LMWL as a diagnostic tool for moisture dynamical processes; we analysed its application in our study region. Specifically, δ18O–δ2H pairs plotting on the LMWL’s upper portion indicate cloud-microphysical processes, while mid-LMWL points typically result from moisture recycling. We investigated points from specific periods (16 to 27 August and 6 to 15 September, 2019) characterised by high surface evaporation, as revealed by the RR record. These points cluster around the LMWL’s middle section (Fig. 2, right panel, red dots). Notably, the red-LMWL’s slope (8.31) exceeds that of the Global Meteoric Water Line (GMWL), aligning with Putman et al.‘s predictions. Notably, our findings corroborate the proposal by Kathyat et al.49, which suggests that monsoon seasons characterised by above-average rainfall derive a substantial portion of their moisture from surface evaporation.

In summary, the precipitation isotopes in the central Indian region are controlled by synoptic-scale monsoon activities represented by large-scale rainfall anomalies, low-pressure systems, intense convective activities and surface evaporation. All of these processes usually deplete the isotopic values. On the other hand, raindrop evaporations tend to increase the isotopic values.

It’s worth noting that signatures of heavy rainfall can be discerned from the analysis of carbonate samples on a sub-seasonal scale. Ghosh et al.50 demonstrated that freshwater shells collected from the periphery of the CMZ near Kolkata recorded extreme rainfall events on a sub-seasonal scale. Such reconstructions could be significantly improved by considering the impact of LPS-induced rainfall and its influence on precipitation isotopes.

The intraseasonal variability of δ 18O and its trend

The isotopic values of rainfall often exhibit a decreasing trend during the monsoon season across the Indian subcontinent, as documented by several studies21,24,51,52. We have observed a similar declining pattern in the Sagar isotope record (see Fig. 2, a to f) and in the records from Bhopal and Dhanbad, as reported by Midhun et al.35.

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain this phenomenon. According to Chakraborty et al.24, the early monsoon season experiences an enhanced rate of plant transpiration, leading to relatively high isotopic values. However, as the monsoon progresses, the proportion of the evapotranspiration decreases. Simultaneously, the contribution of oceanic moisture increases, resulting in an overall decreasing isotopic trend. Midhun et al.35 invoked the concept of accumulative convection to explain δ18O variations during the monsoon season. Zhang et al.52 also proposed a similar mechanism. According to these authors, the upstream water vapor isotopic compositions modulate the downstream precipitation isotopic variability. We hypothesise that an increasing proportion of RR values during the monsoon season (Fig. S7) causes a progressive depletion in precipitation isotopic values. However, we restrict ourselves from performing a detailed analysis to test the available hypotheses since this is the beyond the scope of this study.

Quantifying the effect of LPS on the precipitation isotopes

The study investigates the impact of LPS on isotopic values in precipitation. LPSs generally lead to reductions in isotopic values, but the extent of reduction varies based on several factors. These factors include the strength of LPS (measured by sea level pressure drops), their origin, transport pathways, and associated vertical wind motion.

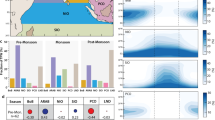

To quantify this effect, we compiled monthly composite isotopic values from various sites within the CMZ. Figure 7 illustrates the relationship between LPS intensity and isotopic values across these sites. Figure 7a represents this relationship for the Bhopal and Dhanbad sites, respectively, for which data is available only for 2013. Multi-year data are available for Sagar, Kolkata, and Pune, as depicted in Fig. 7b, c, and d. Figure 7e presents a composite plot encompassing all the sites except Pune. One particular point, June 2019, appears to be an outlier. This point corresponds to an exceptionally high LPS intensity (monthly composite value of 96 mb). This event was triggered by a very severe cyclonic storm, “Vayu,” that originated near the west coast of India in the second week of June 2019 and moved northward over the following days41.

The scatter plots illustrate the relationship between δ18O and LPS intensity on a monthly basis. Panel (a) depicts this relationship for Bhopal (black) and Dhanbad (red), while panel (b,c) represent Sagar and Kolkata. The lower panels, (d) is for Pune. (e) Represents a composite plot encompassing all the sites with the exception of Pune; while the last panel (f) is the same as (e) but shows the outliers for visualization purposes.

Interestingly, the isotopic values of the rain triggered by Vayu did not deplete linearly with the surface pressure, which recorded an unusually low surface pressure (at the CMZ) of 978.7 hPa on June 15, 2019. This is the lowest surface pressure recorded throughout the LPS observational period from 2013 to 2021 (refer to supplementary table T1). Given the distinct dynamics of severe cyclonic storms and LPSs, we consider this point an outlier (Fig. 7f, shown in red). Hence, we excluded the four LPS days from June 13 to June 16 and re-calculated the monthly composite of the LPS intensity. The revised number was 32mb, which was used in the subsequent calculations.

Most sites, except Pune, exhibit a reasonably strong inverse relationship between LPS intensity and isotopic values. This relationship is illustrated by the regression lines drawn for these sites. However, due to a limited sample size, regression lines were not plotted for Bhopal and Dhanbad. Our analysis indicates that sites within the CMZ generally show significant impacts of LPSs on precipitation isotopic compositions. However, sites outside the CMZ may not be as sensitive to these systems. We have also examined the precipitation isotopes’ behaviour with the SPA and LPS for a few sites in the northern boundary of the CMZ (see Supplementary Note S2b). One year (2018) of precipitation isotopic records from these sites demonstrated their low response to the LPS and associated synoptic systems. Hence, we infer that the isotopic values of rainfall in the southern and northern boundary of the CMZ are not significantly impacted by LPSs.

Considering this general behaviour, we created a composite dataset for these sites that responded strongly to LPSs and regressed the isotopic records against the LPS intensity. The composite plot (Fig. 7e) reveals a reasonably strong inverse correlation (R2 = 0.29), implying that intense low-pressure systems significantly deplete isotopes in precipitation over the CMZ. Notably, the correlation for the Kolkata site is higher than that of Sagar, which is logical given Kolkata’s proximity to the Bay of Bengal. As mentioned, Pune, located in the southern peripheral region of the CMZ, behaves differently. Its precipitation isotopes remain mainly insensitive to low-pressure systems. In contrast, coastal areas along the BOB, such as Kolkata, exhibit the most depleted rainwater isotopic values compared to other CMZ regions.

Our analysis reveals a significant depletion of precipitation isotopes in the northern coastal region of the BOB. In contrast, these isotopes are marginally enriched in the central Indian region. Figure 9 presents the isotopic distributions for different sites, with Fig. 9c and d specifically illustrating the distributions for the CMZ and Kolkata region, respectively. These distributions’ mean and standard deviation are displayed in their respective boxes. Notably, the mean value of Sagar’s δ18O (-5.04‰) is approximately 0.5‰ enriched compared to that of Kolkata (-5.79‰). This observation underscores a fundamental characteristic of precipitation isotopes.

According to the theory of moisture transport and subsequent rainout processes, precipitation isotope values are anticipated to decrease along the moisture transport pathways. If a substantial amount of moisture from the BOB migrates to the CMZ, it should progressively lose its heavier isotopes, resulting in isotopically depleted rainfall. However, our observations contradict this common assumption. The potential reasons for this discrepancy are discussed in the following sections.

-

a.

Raindrop Evaporation: As moisture generated by the BOB moves inland, it undergoes a significant amount of raindrop evaporation. This process results in increased isotopic values.

-

b.

Surface Evaporation: Surface evaporation, particularly the vapours produced by transpiration, contributes to the creation of isotopically enriched moisture and hence rainfall.

-

c.

Moisture Contribution: The contribution of BOB moisture to CMZ rainfall is relatively small compared to the moisture transported from the Arabian Sea, which is known to export moisture having higher isotopic values than that generated by the BOB.

-

d.

Monsoon Trough Movement: The northward movement of the monsoon trough enriches the rainfall (see Fig. 5). This effect is pronounced in the central Indian region and is negligible in the coastal BOB region.

-

e.

Rain-vapor Interaction: Intense isotopic interaction between rain and vapor in the CMZ results in enriched isotopic values of rainfall.

This issue needs to be examined in detail and is beyond the scope of this work.

This section calculates the relative contributions of various atmospheric variables: large-scale rainfall and convective activities represented by the SPA and OLR, LPS, local rainfall, and the recycled ratio (RR) of rainfall on precipitation isotopes. To achieve this, we performed a principal component analysis (PCA) using monthly composites of the variables above, including δ18O and d-excess as input parameters. The results are presented in Fig. S8.

According to the figure, δ18O exhibits an almost out-of-phase relationship with LPS, indicating a strong negative influence. It also forms an acute angle with OLR, suggesting a reasonable positive correlation. Additionally, δ18O forms obtuse angles with local rain, SPA, and RR, implying that these variables negatively influence δ18O to varying degrees. Conversely, d-excess is strongly correlated with RR, indicating that surface evaporation increases d-excess but decreases δ18O. Interestingly, while LPS forms an acute angle with SPA, the correlation (measured as the cosine of the angle between these vectors) is weaker compared to that between local rain and SPA. This is logical, as LPS contributes to monsoon rainfall to varying degrees, reaching up to 60%8. Further details of the PCA are provided in the Supplementary Information (Note S4).

Several investigators have observed that rainfall in the central Indian region and northeast India exhibits an approximately out-of-phase relationship from the intra-seasonal timescale and beyond53. These findings prompted us to investigate whether the precipitation isotopes over the CMZ exhibit an out-of-phase relationship with their counterparts in the north or northeast Indian region. We utilised isotopic data from Darjeeling, which represents the northeastern Indian region and spans the years 2013 to 2018 (as reported in Chakraborty et al.24. To assess isotopic co-variability, we analysed common data points from Darjeeling and the CMZ, focusing on 2013 to 2018.

Figure 8a shows the co-variations between Dhanbad 2013 and Darjeeling 2013. Figure 8b and d illustrate the isotopic behaviour for Sagar-2016, 2017 and 2018 and Darjeeling-2016, 2017, and 2018 records. The visual representation highlights an out-of-phase variability in precipitation isotopes. This indicates a reciprocal relationship, where isotopic lows in the CMZ, driven by large-scale rainfall, LPS passage, and the normal monsoon trough position, correspond to relatively high isotopic values in northeastern India, and the opposite holds true. Overall, our analysis demonstrates that the precipitation isotopic variability in response to the monsoon trough and their observed anti-phasing characteristics with similar records from the southern Himalayan region exhibit coherent behaviour with respect to the precipitation variability. Our findings support the observations of Sinha et al.39, who, based on isotopic analysis of speleothem, proposed di-polar behaviour of rainfall patterns between the CMZ and northeast India during the last millennia but on a centennial timescale.

The co-variability of precipitation isotopes was observed at Dhanbad and Sagar, representing the core monsoon zone, and Darjeeling, representing the Himalayan foothills region. Panel (a) corresponds to the year 2013, while panels (b–d) represent 2016 to 2018. The red lines depict the isotopic records from Darjeeling, while the blue lines represent Dhanbad in panel (a) and Sagar in panels (b–d). Notably, an anti-phasing characteristic is evident in the isotopic records between these two regions.

Kiran Kumar and Singh54 using the isotopic records of speleothems, arrived at a similar conclusion. They observed an inverse relationship between rainfall patterns in Central India and Northeast India, particularly during El Niño periods. Our observations, which are based on precipitation isotopes, thus offer a conceptual framework that supports these findings, which were initially derived from speleothem analyses.

Paleoclimatic implications

Reconstructing paleo-monsoons often involves isotopic analysis of carbonates, including terrestrial speleothems and marine fauna bearing carbonates. The underlying assumption is that the isotopic signal of past rainfall is particularly well-preserved in the layered structure of the geological deposits. By retrieving isotopic records from these archives and applying the concept of the amount effect, we can document past rainfall variability.

Modern-day precipitation isotopic analysis can offer valuable insights into regions best suited for paleo-climatic studies. Proxy analyses typically provide a ‘mean climate’ signal and do not usually record extreme events. This concept can be explained in terms of the distribution function. A normally distributed parameter would have the highest count around the mean value, with other values symmetrically decreasing on either side of the mean.

According to the Central Limit Theorem, if we take numerous samples from a population and calculate the mean of each sample, the means will form a normally distributed pattern. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect precipitation isotopic values to follow a normal distribution pattern. We test this hypothesis for the CMZ and its adjacent region.

The precipitation isotope distribution patterns of Pune and Ahmedabad are illustrated in Fig. 9a and b, while Fig. 9c and d depict those for the CMZ and the Kolkata region. A statistical examination reveals that the δ18O values of Pune and Ahmedabad do not follow a normal distribution. However, the isotopic values of the CMZ and the Kolkata region are approximately normally distributed.

The distribution patterns of precipitation oxygen isotopes for four distinct regions-Pune (a), Ahmedabad (b), the Core Monsoon Zone (c), and Kolkata (d), are presented. For each region, the mean and standard deviation are calculated and mentioned in the top left corner of the respective boxes. Utilising these mean values, a normal distribution function is plotted for each site, depicted by the black line. The diagram in the right panel (e) illustrates the distribution functions of all sites aligned on a common x-axis, highlighting their relative variability with an arbitrary y-axis value.

The distribution patterns of δ18O for Pune, Ahmedabad, CMZ, and Kolkata are depicted through a ridgeline plot in Fig. 9e. This plot allows for a comparative analysis of these regions on a shared x-axis. The regions of Pune and Ahmedabad exhibit a high concentration of data around their respective mean values, indicating a pronounced central tendency and lower variability. Conversely, the CMZ and Kolkata regions show smaller peaks, suggesting a lower data density around the central values. The relatively flat distributions in these regions indicate a more uniform distribution, suggesting a less pronounced central tendency. Therefore, these regions, with their broader isotopic precipitation signal, are more inclusive and better suited for proxy record analysis.

Conclusions

This study investigates the impact of synoptic-scale processes on precipitation isotopes within India’s CMZ. We analysed precipitation isotope data from several sites in the CMZ, including multi-year records at Sagar and the existing precipitation records and other atmospheric variables. LPSs originating in the Bay of Bengal significantly influence rainfall patterns. Our findings show:

-

1.

LPSs consistently deplete isotopic values, with an inverse correlation between LPS intensity and precipitation isotopic values, particularly in Kolkata.

-

2.

Large-scale convective activities contribute to isotopic depletion, while sporadic surface evaporation enhances the secondary parameter, d-excess.

-

3.

Extreme weather conditions (severe cyclonic events) non-linearly reduce isotopic values.

-

4.

CMZ precipitation isotopic values capture the mean climate signal, exhibiting a near-normal distribution.

These results demonstrate the systematic influence of LPS on precipitation isotopes within the CMZ, making it an ideal region for proxy records to capture monsoon rainfall variability.

Materials and methods

Study area and site

Sagar is located at the central Indian location with 78.7582 °E longitude, 23.8173 °N latitude, and 598 m AMSL (above the mean level) in the Madhya Pradesh state (Fig. 1b). The site has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cwa) with hot summers, a somewhat cooler monsoon season, and cool winters. The monsoon season is from June to September and can have very heavy rainfalls. According to the IMD data, the average rainfall for the summer monsoon season (JJAS) at this site from 2010 to 2020 was 1112.5 mm. The seasonal rainfall in the above-mentioned decade contributed little over 90% of the annual rainfall.

We collected daily rainwater samples at 08:30 (local time) integrated for the past 24 h. We employed an Ordinary Rain Gauge with a built-in funnel, secured over a 1.5 L storage reservoir, housed within a fibre enclosure. This design minimized direct radiation and evaporation. Rainfall amounts were measured using a calibrated cylinder. Additionally, a table-tennis ball was placed inside the funnel to prevent evaporation and restrict dust particles. At the end of each 24-hour period, rainfall was recorded, and the sample was transferred to a 15 mL leak-proof bottle labelled with date, time and location, and wrapped with parafilm for additional protection against evaporative loss. We collected 38, 33, 43, 76, 42, and 60 rainwater samples from 2016 to 2021. Additionally, we collected rainwater samples from the following sites. Barabanki, Jaludi Nagar, and Paramanek Nagar, near Lucknow (in 2018), Pune (in 2019) and Kolkata (in 2019) which are approximately situated in the northern, southern and eastern limits of the CMZ (Fig. 1b shows their location). We analysed the rainwater samples at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM), Pune, and Physical Research Laboratory, Ahmedabad, using an LGR Water and Water Vapor Analyzer (Model: TIWA-45-EP). The results were calibrated to the VSMOW-SLAP scale using the three-point normalization method55. To ensure accuracy, we used three in-house standards: IITM-A (δ18O = -1.61 ± 0.20‰; δ2H = -10.15 ± 0.22‰), IITM-PU2 (δ18O = -3.85 ± 0.12‰; δ2H = -19.39 ± 0.25‰), IITM-KI (δ18O = -9.90 ± 0.20‰; δ2H = -50.96 ± 0.32‰) for normalisation, and IITM-RO (δ18O = -2.62 ± 0.120‰; δ2H = -13.43 ± 0.22‰) as a control standard for monitoring the instrument’s performance. Stable isotope ratios are expressed in delta notation (per mil, ‰), calculated relative to the Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW) reference standard. All values and uncertainties were verified against the primary reference materials VSMOW2 and SLAP2. Since oxygen and hydrogen isotope variations show a strong positive correlation, we present only the oxygen isotopic records here.

Precipitation data, standardized rainfall index, outgoing longwave radiation, and evapotranspiration data

Apart from the rain gauge data, we have used the gridded rainfall data to calculate the standardized precipitation anomaly. The Standardized Precipitation Anomaly (SPA) is widely used to study the intra-seasonal variability of monsoon56. It is based on the probability of precipitation for a given time scale and location. The SPA for the CMZ is calculated using the long-term average (LTA) rainfall data for the region (65° − 88°E, 18° − 28°N) using the formula below.

where Pyear is the summer monsoon rainfall for a given year on a daily scale, Pmean is the mean rainfall, and Pst is the standard deviation of rainfall for the JJAS season based on LTA data. This index quantitatively estimates the monsoon’s active and break phases1. For example, high positive (negative) values represent heavy (low) rainfall over the CMZ.

We used outgoing longwave radiation (OLR) data to investigate convective activities. Low OLR values (< 200 W/m2) correspond to deep tropical convection57,58. The daily-scale OLR data was sourced from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). We computed average OLR values over an area similar to the previously mentioned CMZ and generated time series data for the monsoon seasons.

Low-pressure systems

Several investigators used different techniques to identify the LPSs—the traditional method for identifying LPSs involved detecting closed isobars on surface pressure charts59. Godbole5 used dynamical parameters such as sea level pressure, meridional and zonal winds, and vorticity to detect the LPSs. Thomas et al.7 used geopotential height anomaly and relative vorticity thresholds to track these systems. Using a novel tracking algorithm, we follow Praveen et al.8 to objectively detect and track the LPSs. This method resembles the traditional identification and tracking algorithm that uses closed isobars on surface pressure charts. In brief, the method looks for the closed contours of the sea level pressure (SLP) in a specific area. In our case, this is the core monsoon zone of India and the neighbouring coastal areas where the LPSs are typically formed (box with red outline in Fig. 1b). The intensity of the LPS is measured by the pressure difference from the centre of the closed contour with the lowest SLP to the farthest closed contour within the box. The higher the number (expressed in millibar, or mb), the more intense the LPS is. Table T1 in the supplementary data summarises the information, such as the intensity, tracks, number, etc., derived for the LPSs detected from 2013 to 2021. We follow the following norm: one ‘LPS day’ is at least a single LPS occurrence. An ‘LPS event’ is a group of LPS days collectively formed an LPS track.

Monsoon trough

We performed the following exercise to investigate how the monsoon trough (MT) affects the precipitation δ18O. We used the IMD daily weather charts that show the MT as a dashed line from the west-northwest of India to the east (north Bay of Bengal), roughly parallel to northern India’s border. We measured the perpendicular distance from Sagar, our rainwater collection site, to the MT. The distance is positive when the MT is north of Sagar and negative when it is south. When the MT is on or near Sagar, heavy rainfall usually occurs in this area.

Recycling ratio (RR)

The recycling ratio (RR, %) of precipitation is the ratio of local evapotranspiration (ET) contributing to precipitation to the total precipitation. Here we use Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) with water vapor tracer (WVT) module based on Eulerian method60. The WVT method uses a moisture tagging approach in global or regional climate models, enabling all physical processes affecting atmospheric moisture such as advection, diffusion, convection, and cloud microphysics to be represented realistically, capturing the complete lifecycle of moisture until it falls back as precipitation.

In this method, a region is tagged (here, the Indian land region), and moisture from evapotranspiration is tracked. Consequently, recycled rainfall originates partly from moisture within the same region and partly from moisture advected from nearby regions. In comparison to diagnostic methods61, which can estimate RR at best on a seasonal time scale, the WVT or online Eulerian method can provide estimates of RR at each model time step. WRF-WVT model forcing (initial and boundary conditions) is taken from the 6-hourly ERA5 reanalysis (1981–2021). Here we have used daily estimate of RR for selected domain box, which includes Sagar (22–26°N, 75–85°E). A detailed description of this method is provided in the Supplementary Information (Note: S5).

Data availability

Precipitation isotopic data observed during this study is publicly available at: https://zenodo.org/uploads/11180245. Data is also provided as Supplementary Materials. Precipitation isotopic data for Bhopal and Dhanbad used in this study were sourced from the study by Midhun et al.35. Additional precipitation isotopic data for Pune, Kolkata, and Darjeeling were sourced from Chakraborty et al.24.The tracks for the low-pressure systems generated during the study are included in this published article [see supplementary information file: LPS-tracks-2013-2021.csv].The data used to calculate the Standardized Precipitation Anomaly (SPA) were sourced from the Indian Monsoon Data Assimilation and Analysis (IMDAA), as detailed in the work of Indira Rani et al.62. The ERA5 reanalysis data product, which includes variables such as mean sea level pressure, and relative humidity were obtained from Hersbach et al.63. This data product was also used to determine the recycled ratio. Data on outgoing longwave radiation (OLR) was retrieved from the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) website; https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/metadata/landing-page/bin/iso?id=gov.noaa.ncdc:C00875.

References

Rajeevan, M., Gadgil, S. & Bhate, J. Active and break spells of the Indian summer monsoon. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 119, 229–247 (2010).

Annamalai, H. & Slingo, J. Active/break cycles: Diagnosis of the intraseasonal variability of the Asian summer monsoon. Clim. Dyn. 18, 85–102 (2001).

Krishnan, R., Zhang, C. & Sugi, M. Dynamics of breaks in the Indian summer monsoon. J. Atmos. Sci. 57, 1354–1372 (2000).

Pattanaik, D. R. et al. Active-break transitions of monsoons over India as predicted by coupled model ensembles. Pure Appl. Geophys. 177, 4391–4422 (2020).

Godbole, R. V. The composite structure of the monsoon depression. Tellus A 29, 2540 (1977).

Sorland, S. L. & Sorteberg, A. The dynamic and thermodynamic structure of monsoon low-pressure systems during extreme rainfall events. Tellus A 67, 27039 (2015).

Thomas, T. M., Bala, G. & Srinivas, V. V. Characteristics of the monsoon low pressure systems in the Indian subcontinent and the associated extreme precipitation events. Clim. Dyn. 56, 1859–1878 (2021).

Praveen, V., Sandeep, S. & Ajaymohan, R. S. On the relationship between mean monsoon precipitation and low-pressure systems in climate model simulations. J. Clim. 28, 5306 (2015).

Hunt, K. M., & Fletcher, J. K. The relationship between Indian monsoon rainfall and low-pressure systems. Clim. Dyn. 53(3), 1859–1871 (2019).

Goswami, B. N. et al. Increasing trend of extreme rain events over India in a warming environment. Science 314, 1442–1445 (2006).

Sinha, N., Chakraborty, S. & Chattopadhyay, R. Isotopic investigation of the moisture transport processes over the Bay of Bengal. J. Hydrol. X 2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydroa.2019.100021 (2019).

Sengupta, S. et al. Signatures of monsoon intra-seasonal oscillation and stratiform process in rain isotope variability in Northern Bay of Bengal and their simulation by isotope enabled general circulation model. Clim. Dyn. 55, 1649–1663 (2020).

Kurita, N. et al. Intraseasonal isotopic variation associated with the Madden-Julian oscillation. J. Geophys. Res. 116. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JD015209 (2011).

Chakraborty, S., Belekar, A. R. & Datye, A. Sinha isotopic study of intraseasonal variations of plant transpiration: An alternative means to characterize the dry phases of monsoon. Sci. Rep. 8, 8647. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-26965-6 (2018).

Srivastava, R. et al. Monsoon onset signal in the stable oxygen and hydrogen isotope ratios of monsoon vapor. Atmos. Environ. 108, 117–124 (2015).

Fousiya, A. A. et al. Modulation of the precipitation isotopes by the dynamic and thermodynamic variables of the atmosphere in southern parts of India. Water Resour. Res. 58, e2021WR030855. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021WR030855 (2022).

Lekshmy, P. R., Midhun, M., Ramesh, R., & Jani, R. A. 18O depletion in monsoon rain relates to large scale organized convection rather than the amount of rainfall. Sci. Rep. 4, 5661 (2014).

Lekshmy, P. R., Midhun, M. & Ramesh, R. Amount dependency of monsoon rainfall δ 18O on multiple time scales: Observations from south western India. Clim. Dyn. 53, 933–941 (2019).

Rahul, P., Ghosh, P., Bhattacharya, S. K. & Yoshimura, K. Controlling factors of rainwater and water vapor isotopes at Bangalore, India: Constraints from observations in 2013 Indian monsoon. J. Geophys. Res. 121, 13,936–13,952 (2016).

Deshpande, R., Maurya, A., Kumar, B., Sarkar, A. & Gupta, S. Rain-vapor interaction and vapor source identification using stable isotopes from semiarid western India. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 115, 23311 (2010).

Oza, H. et al. Hydrometeorological processes in semi-arid western India: Insights from long term isotope record of daily precipitation. Clim. Dyn. 54, 2745–2757 (2020).

Sengupta, S. & Sarkar, A. Stable isotope evidence of dual (Arabian Sea and Bay of Bengal) vapour sources in monsoonal precipitation over north India. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 250, 511–521 (2006).

Breitenbach, Adkins, J. F. et al. Strong influence of water vapour source dynamics on stable isotopes in precipitation observed in Southern Meghalaya, NE India. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 292, 212–220 (2010).

Chakraborty, S. et al. Linkage between precipitation isotopes and biosphere-atmosphere interaction observed in northeast India. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-022-00231-z (2022).

Jeelani, G., Deshpande, R. D., Galkowski, M. & Rozanski, K. Isotopic composition of daily precipitation along the southern foothills of the himalayas: Impact of marine and continental sources of atmospheric moisture. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 8789–8880 (2018).

Lone, A. M., Achyuthan, H. & Chakraborty, S. Controls on the isotopic composition of daily precipitation characterized by dual moisture transport pathways at the monsoonal margin region of North-Western India. J. Hydrol. 588, 125106 (2020).

Adhikari, N., Gao, J., Yao, T., Yang, Y. & Dai, D. The main controls of the precipitation stable isotopes at Kathmandu, Nepal. Tellus B: Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 72(1), 1721967 (2020).

Hassenruck-Gudipati, H. J. et al. Moisture sources and pathways determine stable isotope signature of himalayan waters in Nepal. AGU Adv. 4, e2022AV000735. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022AV000735 (2023).

Dar, S. S. & Ghosh, P. Estimates of land and sea moisture contributions to the monsoonal rain over Kolkata, deduced based on isotopic analysis of rainwater. Earth Syst. Dyn. 8, 313–321. https://doi.org/10.5194/esd-8-313-2017 (2017).

Midhun, M., Ramesh, R. & Lekshmy, P. R. Amount dependency of monsoon rainfall δ18O on multiple time scales: Observations from south western India. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40(1), 933–941 (2013).

Lekshmy, P. R., Midhun, M. & Ramesh, R. Role of moisture transport from Western Pacific region on water vapor isotopes over the Bay of Bengal. Atmos. Res. 265, 105895 (2022).

Chakraborty, S. et al. Atmospheric controls on the precipitation isotopes over the Andaman Islands, Bay of Bengal. Sci. Rep. 6, 19555. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep19555 (2016).

Sinha, N. & Chakraborty, S. Isotopic interaction and source moisture control on the isotopic composition of rainfall over the Bay of Bengal. Atmos. Res. V 35, 104760 (2020).

Munksgaard, N. C. et al. Data descriptor: Tropical daily observations of stable isotope compositions in rainfall and calculated stratiform rainfall fractions. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50973-9 (2019).

Midhun, M. et al. The effect of monsoon circulation on the stable isotopic composition of rainfall. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 123, 5205–5221 (2018).

Berkelhammer, M. et al. Persistent multidecadal power of the Indian Summer Monsoon, Earth and Planet. Sci. Lett. 290(1–2), 166–172 (2010).

Sinha, A., Cannariato, K. G. & Stott, L. D. A 900-year (600–1500 A.D.) record of the Indian summer monsoon precipitation from the core monsoon zone of India. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34(16), L16707 (2007).

Dixit, Y. et al. Abrupt weakening of the Indian summer monsoon at 8.2 Kyr B.P., Earth and Planet. Sci. Lett. 391, 16–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2014.01.026 (2014).

Sinha, A., Berkelhammer, M., Stott, L. & Mudelsee, M. The leading mode of Indian summer Monsoon precipitation variability during the last millennium. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L15703. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GL047713 (2011).

Kumar, B., Rai, S. P. & Kumar, S. Isotopic characteristics of Indian precipitation. Water Res. Res. 46, W12548 (2010).

Bhargavi, V. S. L., Rao, V. B. & Naidu, C. V. An unusual 2019 Indian summer monsoon. A glimpse of climate change? Theor. Appl. Climatol. 155, 4963–4989 (2024).

Froehlich, K. et al. Deuterium excess in precipitation of Alpine regions—Moisture recycling. Isot. Environ. Health Stud. 44(1), 61–70 (2008).

Putman, A. L., Fiorella, R. P., Bowen, G. J. & Cai, Z. A global perspective on local meteoric water lines: Meta-analytic insight into fundamental controls and practical constraints. Water Res. Res. 55, 6896–6910 (2019).

Crawford, J. et al. Precipitation stable isotope variability and subcloud evaporation processes in a semi-arid region. Hydrol. Process. 31(1), 20–34 (2017).

Clark, I. D. & Fritz, P. Environmental Isotopes in Hydrogeology (CRC Press, 1997).

Welp, L. R. et al. A meta-analysis of water vapor deuterium-excess in the midlatitude atmospheric surface layer. Glob. Biogeochem. Cyles 26, GB3021. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GB004246 (2012).

Merlivat, L. & Jouzel, J. Global climatic interpretation of the deuterium-oxygen 18 relationship for precipitation. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 84, 5029–5033 (1979).

Kurita, N. Water isotopic variability in response to mesoscale convective system over the tropical ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 10376–10390 (2013).

Kathayat, G. et al. Interannual oxygen isotope variability in Indian summer monsoon precipitation reflects changes in moisture sources. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 96. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00165-z (2021).

Ghosh, P., Rangarajan, R., Thirumalai, K. & Naggs, F. Extreme monsoon rainfall signatures preserved in the invasive terrestrial gastropod Lissachatina fulica. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 18, 3758–3770. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GC00704 (2017).

Ahmed, N. et al. Atmospheric factors controlling stable isotope variations in modern precipitation of the tropical region of Bangladesh. Isot. Environ. Health Stud. 56(3), 220–237 (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Controls on stable water isotopes in monsoonal precipitation across the Bay of Bengal: Atmosphere and surface analysis. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL102229 (2023).

Kulkarni, A. et al. Role of intra-seasonal oscillations in modulating Indian summer monsoon rainfall. Clim. Dyn. 36, 1005–1021 (2011).

Kiran Kumar, P., Singh, A. Increase in summer monsoon rainfall over the northeast India during El Niño years since 1600. Clim. Dyn. 57, 851–863 (2021).

Paul, D., Skrzypek, G. & Fórizs, I. Normalization of measured stable isotopic compositions to isotope reference scales—A review. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 21, 3006–3014 (2007)

Dey, A. et al. The intraseasonal fluctuation of Indian summer monsoon rainfall and its relation with monsoon intraseasonal oscillation (MISO) and Madden Julian oscillation (MJO). Theor. Appl. Climatol. 148, 819–831 (2022).

Gadgil, S. The Indian Monsoon and its variability. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 31, 429–467 (2023).

Lau, K. M., Wu, H. T. & Bony, S. The role of large-scale atmospheric circulation in the relationship between tropical convection and sea surface temperature. J. Clim. 10(3), 381–392 (1997).

Sikka, D. R. A study on the monsoon low pressure systems over the Indian region and their relationship with drought and excess monsoon seasonal rainfall. Center for Ocean–Land–Atmosphere Studies Tech. Rep. 217, p. 61.

Insua-Costa, D. & Miguez-Macho, G. A new moisture tagging capability in the Weather Research and forecasting model: Formulation, validation and application to the 2014 Great Lake-effect snowstorm. Earth Syst. Dyn. 9, 167–185 (2018).

Eltahir, E. A. B. & Bras, R. L. Precipitation recycling in the Amazon basin. Q. J. R Meteorol. Soc. 120, 861–880 (1994).

Rani, I. et al. IMDAA: High Resolution Satellite-era reanalysis for the Indian Monsoon Region. J. Clim. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-20-0412.1 (2021).

Hersbach, H. et al. ERA5 hourly data on pressure levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS) (2023). https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.bd0915c6.

Acknowledgements

The Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM), an autonomous institute under the Ministry of Earth Sciences, Government of India, is fully funded by the government. The precipitation isotopic data was generated at the Stable Isotopic Laboratory of IITM as part of the Coordinated Research Project (CRP) awarded to the corresponding author by the International Atomic Energy Agency in Vienna, Austria. The specific CRP, titled “Isotope Variability of Rain for Assessing Climate Change Impact”, had project number F-31006 (IAEA Research Agreement No: 23822/R0). We thank Dipak Kumar Parua, Sudeep Nayan, Shivam, and Praveen Kumar for their technical support in collecting rainwater samples. Scientific discussions with Prof. B.N. Goswami helped us improve the presentation. We are thankful to Mrs. Shompa Das, the head of the IITM Library and her colleagues for making the IMD daily weather reports and other resources available to us. Language service provided by AI tools, such as Microsoft Copilot and Grammarly.com, is appreciated.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.C. Conceptualized, did formal analysis and wrote the original draft. A.S.(1), V.P., P.K.D., S.K.S., Y.S., and N.S. carried out formal analysis, made graphics.A.D., M.G.Y., N.T., R.K.T. and A. S.(2) undertook methodology. S.C., P.K.D., A.S.(1), V.P., R.C., S.K.S., M.Y., A.S. reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 3

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chakraborty, S., Sarkar, A., Datye, A. et al. Precipitation isotopes and monsoon dynamics in the core monsoon zone of India. Sci Rep 15, 6761 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88640-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88640-x