Abstract

Aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (aSAH) is a type of stroke with high mortality and morbidity. This study aimed to identify novel aSAH risk factors by combining machine learning (ML) and traditional statistical methods. Using the UK Biobank, we identified aSAH cases via hospital-based ICD codes and analysed 618 baseline variables covering demographics, lifestyle, medical history, and physical measurements. The CatBoost ML algorithm and Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) identified the top 25 variables most influential in predicting aSAH. Logistic regression further described these variables while adjusting for established aSAH risk factors. Among 501,847 participants, 893 aSAH cases were identified. ML identified 214 variables with non-zero SHAP values. Logistic regression of the top 25 variables revealed four potential novel aSAH risk factors. Increased aSAH risk was associated with mean sphered cell volume (OR 1.02, 95% CI 1.00-1.03) and tea intake (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.01–1.05). Decreased aSAH risk was associated with peak expiratory flow (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.66–0.96), and haematocrit percentage (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.95-1.00). Future research should validate these findings and explore the potential non-linear relationships and interactions indicated by the ML models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (aSAH) is a type of stroke that occurs when an intracranial aneurysm ruptures1. Despite accounting for only 10% of all strokes2, aSAH is particularly devastating due to its early age of onset and high mortality rate, leading to a number of potential life years lost comparable to those lost to ischaemic stroke, the most common type of stroke3. Current understanding of the pathogenesis of aSAH remains limited4. Established risk factors include age, female sex, hypertension, smoking, and excessive alcohol consumption5. However, prediction models incorporating these established risk factors are only moderately able to discriminate between aSAH cases and controls6,7. Thus, knowledge of additional risk factors is required to identify people at risk of aSAH.

Machine learning has emerged as a promising strategy for identifying novel risk factors for various medical conditions8,9,10. Unlike traditional statistical methods, machine learning can process large and diverse datasets, uncover complex non-linear associations and their interactions, and does not require precise model specification before analysis11,12,13. However, one limitation of machine learning is that the models it generates can be difficult to interpret and explain in human terms14. Integrating machine learning with traditional statistical methods could provide a comprehensive solution by leveraging the depth and complexity of machine learning analysis while preserving the interpretability of traditional models8.

In this study, we aimed to identify new risk factors for aSAH by combining machine learning and statistical methods, using data from the United Kingdom (UK) Biobank’s population-based cohort.

Results

We identified 893 aSAH patients among 501,847 participants (Table 1). The aSAH patients tended to be older, predominantly female, more frequently current smokers, and more likely to have hypertension compared to the individuals who did not develop aSAH. Finally, aSAH patients were less likely to drink alcohol, but if they did, they drank more often.

Machine learning model

Initial pre-processing resulted in 235 variables to be used by the CatBoost model of which 214 variables were identified with a mean absolute SHAP value greater than 0 (Supplementary Table 1). The 25 variables with the highest mean absolute SHAP values were: peak expiratory flow, smoking status, age at baseline, impedance of whole body, sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG), basal metabolic rate, C-reactive protein (CRP), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), mean sphered cell volume, sitting height, hand grip strength, forced vital capacity, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), haematocrit percentage, urea, number of self-reported non-cancer illnesses, trunk fat mass, systolic blood pressure, Townsend deprivation index at recruitment, body mass index (BMI), creatinine (enzymatic) in urine, impedance of leg, lymphocyte count, tea intake, and neutrophil percentage (Fig. 1).

Traditional statistical model

We did not further investigate age at baseline and smoking status, as they were already included as established risk factors. We also excluded whole body impedance, basal metabolic rate, and trunk fat mass from our study due to their high variance inflation factors, leaving 20 potential risk factors for further analysis (Table 2). A brief description of these potential risk factors can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

We identified 8 of the 20 variables that were univariably associated with an increased risk of aSAH. These included log-transformed SHBG levels (OR 1.46, 95% CI 1.26–1.69), log-transformed CRP levels (OR 1.09, 95% CI 1.02–1.17), mean sphered cell volume (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.01–1.04), urea (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.00–1.11), number of self-reported non-cancer illnesses (OR 1.08, 95% CI 1.05–1.11), systolic blood pressure (OR 1.01, 95% CI 1.00–1.01), impedance of leg (OR 1.00, 95% CI 1.00–1.01), and tea intake (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.01–1.05). After adjusting for established risk factors, the associations remained statistically significant for log-transformed SHBG levels (OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.09–1.53), mean sphered cell volume (OR 1.02, 95% CI 1.00–1.03), impedance of leg (OR 1.00, 95% CI 1.00–1.01), and tea intake (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.01–1.05). A sensitivity analysis revealed that compared to low tea intake (less than 2 cups a day), medium tea intake (between 2 and 5 cups) was associated with a decreased aSAH risk (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.76–1.05), whereas high intake was associated with an increased risk (OR 1.11, 95% CI 0.94–1.32). We found that the increased aSAH risk associated with high tea intake was more pronounced in women than in men (Supplementary Fig. 2).

We also found 7 of the 20 variables to be univariably associated with a decreased aSAH risk: log-transformed peak expiratory flow (OR 0.60, 95% CI 0.53–0.69), IGF-1 (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.97–0.99), sitting height (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.95–0.97), hand grip strength (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.98–0.99), log-transformed forced vital capacity (OR 0.51, 95% CI 0.42–0.62), haematocrit percentage (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.95–0.98), and BMI (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.96–0.99). After adjusting for established risk factors, the associations remained statistically significant for log-transformed peak expiratory flow (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.66–0.96), haematocrit percentage (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.95–1.00), and BMI (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.96–0.99). Finally, we found an interaction between haematocrit percentage and age, with older individuals with low haematocrit percentage at the highest risk of aSAH (Supplementary Fig. 3).

For the remaining 5 variables—HbA1c, Townsend deprivation index, log-transformed creatinine in urine, lymphocyte count, and neutrophil percentage—we did not find any statistically significant associations with aSAH.

Discussion

Using a combination of machine learning and traditional statistical approaches, we identified four variables associated with an increased risk of aSAH. These included log-transformed SHBG, mean sphered cell volume, leg impedance, and tea consumption. In contrast, three variables were linked to a decreased risk of aSAH: log-transformed peak expiratory flow, haematocrit percentage, and BMI.

Our analysis identified two new potential risk factors for aSAH. The first, mean sphered cell volume, measures red blood cells in a spherical state. Although no prior studies have linked mean cell sphered volume to aSAH, it could be associated with aSAH via macrocytosis, which leads to increased blood viscosity and possibly a higher risk of rupture15. However, the small effect size we observed for this risk factor may suggest alternative mechanisms. For example, the effect may be mediated through other risk factors associated with high mean cell sphered volume, such as vitamin B12 deficiency16. In turn, vitamin B12 deficiency may be associated with extreme forms of the established aSAH risk factors of alcohol abuse and smoking17. Although we have adjusted for alcohol use and smoking in our analysis, there remains a risk of residual confounding of their extreme forms. Finally, our research suggests an increased risk of aSAH with high tea consumption, contrasting with studies indicating no association or a reduced risk18,19,20. This discrepancy might be due to differences in the amount of tea consumed. For instance, tea intake in the UK Biobank averages 3.5 cups a day, considerably higher than the at least 1 cup a day defined in other studies. Our sensitivity analysis confirmed this, with a reduced aSAH risk observed for moderate tea intake, and an increased aSAH risk for high intake. Moderate tea consumption may reduce aSAH risk due to antioxidants and anti-inflammatory compounds in tea that improve vascular health and lower blood pressure18. These compounds may strengthen blood vessel walls, reducing the likelihood of aneurysms. However, excessive tea intake could increase aSAH risk because high levels of caffeine can elevate blood pressure and induce vascular stress21.

Our analysis also identified two new variables potentially associated with a decreased aSAH risk. We found an inverse relationship between peak expiratory flow and the risk of aSAH. Peak expiratory flow is an indicator of lung function which measures the fastest speed at which a person can exhale air after a maximal inhalation. Similar inverse associations between stroke risk and peak expiratory flow have been documented in previous studies22,23. Although peak expiratory flow is commonly linked with cardiovascular risk factors like hypertension and smoking24, our findings indicate an association even after adjusting for these factors. One possible explanation is that low peak expiratory flow may reflect diminished lung function and possibly chronic hypoxia, which can contribute to vascular remodelling and alterations in blood pressure regulation25. This condition could lead to changes in brain blood vessels, increasing their susceptibility to aneurysm formation or exacerbating existing arterial weaknesses. Finally, we identified an inverse relationship between the risk of aSAH and haematocrit percentage, which is the proportion of red blood cells in the bloodstream. Despite previous research reporting no link between aSAH occurrence and haematocrit levels26, these levels are often low in patients at hospital admission and can indicate a higher risk of death27.

Our results have similarly highlighted several potential risk factors for aSAH that were previously suggested by research but not conclusively established. These include BMI and leg impedance, b relating to body size. The data on the relationship between body size and aSAH risk is inconsistent5,28,29, similar to our study. We found a decreased aSAH risk associated with BMI and a small increased risk associated with leg impedance. It has been speculated that very lean individuals might have nutritional deficiencies predisposing them to aSAH26. Alternatively, the association between aSAH and body size might reflect epidemiological biases such as unmeasured confounding or selection bias30.

Our analysis also corroborates prior research. The CatBoost machine learning algorithm identified age and smoking status as important predictors, a finding supported by our statistical analysis. Although the machine learning model did not directly identify female sex, a well-established risk factor5, it did identify SHBG as important. SHBG is a liver-produced protein that binds to sex hormones such as testosterone and oestrogen, regulating their availability in the body. There is evidence that the elevated aSAH risk in women may be hormonally driven31, making SHBG levels, or other hormone-related variables, potentially more relevant predictors of aSAH risk than merely biological sex. Similarly, the Catboost model favoured numerical variables such as systolic blood pressure over binary ones like the presence or absence of hypertension. Contrary to initial expectations, only a slight increase in aSAH risk was observed among heavy drinkers, which lost statistical significance after adjusting for other risk factors. The association between alcohol use and aSAH is still under investigation28, and there is some evidence that the association only exists for excessive use32. Our categorical definition of alcohol use based on frequency of use may have missed important information on current or past amounts of alcohol intake. Intriguingly, those who reported never drinking alcohol showed the highest aSAH risk, which could reflect prior excessive consumption or other health issues leading them to abstain.

The CatBoost machine learning algorithm identified several variables that did not show statistically significant associations in the traditional statistical model. These included CRP, forced vital capacity, HbA1c, Townsend deprivation index, creatinine, lymphocyte count, and neutrophil percentage. These variables might exhibit non-linear associations with aSAH or depend on interaction terms, making them detectable by CatBoost but not by logistic regression. For example, HbA1c may only relate to aSAH beyond a certain threshold, as aSAH is associated with diabetes5. Similarly, variables such as forced vital capacity, hand grip strength, urea levels, and IGF-1, which were univariably associated with aSAH but not after adjustment for established risk factors, may be either confounded or indicative of an unknown mediator role. For example, the observed increased aSAH risk in smokers might be partially explained by elevated CRP levels33. These are observational findings, however, and further validation is necessary to substantiate these claims.

This study has several strengths. Firstly, the use of a large dataset, including numerous individuals and variables, facilitated the identification of sufficient cases and variables for a hypothesis-generating approach. Additionally, variables in the UK Biobank are systematically assessed for each individual at baseline, enabling us to evaluate the prognostic significance of each variable. This systematic assessment of variables also allowed for proper adjustment of established risk factors, thereby reducing false positives. Finally, by integrating machine learning with statistical methods, we were able to both filter and characterise the variables associated with aSAH. Relying solely on machine learning would not have permitted quantification of predictor effects, just as relying solely on statistical methods would have precluded analysis of the entire dataset.

This study also had several limitations. First, the rarity of aSAH resulted in poor model performance in the traditional statistical models. Consequently, automatic model selection procedures often yielded an empty null model, restricting our statistical analysis. This limitation confined our statistical modelling to linear associations, as exploring non-linear relationships or interactions was not feasible. Efforts to address class imbalance through sampling or weighting methods produced unreliable SHAP values, failing to identify established aSAH risk factors such as age and smoking. As a result, we chose to present our findings without adjustments for class imbalance. Moreover, the rarity of the condition necessitated analysing the entire dataset rather than dividing it into development and validation cohorts, as is typical in machine learning studies34. This limitation meant we could conduct only minimal internal validation, and our results might not be generalisable to an external dataset. Another limitation is the demographic composition of the UK Biobank participants, who are predominantly older, Caucasian, and from upper-middle-class backgrounds35. This demographic skew may limit the generalizability of our findings to other populations. We similarly faced limitations due to a lack of radiographic information, preventing us from verifying whether individuals with aSAH-related ICD codes actually had a ruptured aneurysm. Consequently, we were also unable to investigate known aneurysmal risk factors such as aneurysm size and shape. Finally, we did not adjust for multiple comparisons, as the goal of our study was to generate hypotheses by identifying as many potential risk factors for aSAH as possible, without assuming causal relationships among these variables. Furthermore, the selection of potential risk factors was not based on statistical significance. Nevertheless, the lack of such adjustments stress the need to externally validate these initial signals to ensure their reliability and generalizability.

In conclusion, we have identified four new potential risk factors for aSAH. Mean sphered cell volume and tea intake were associated with increased aSAH risk. In contrast, peak expiratory flow and haematocrit percentage were associated with decreased aSAH risk. Our research builds upon previous studies by providing further evidence that body size is associated with aSAH risk, by suggesting that hormonal levels may partially explain the higher aSAH risk among women, and by confirming previously established risk factors. Future studies should use larger sample sizes to validate these preliminary findings. Additionally, special attention should be given to factors identified by the Catboost algorithm that were not statistically significant in the logistic regression model. This could indicate potential non-linearities or interaction effects of these factors which are detectable by CatBoost but not by logistic regression.

Methods

Data source

The UK Biobank, an ongoing large-scale prospective population-based cohort study, has collected health-related data from over 500,000 participants, recruited between 2006 and 2010, who were aged 37 to 73 years at baseline36. A systematic medical history was taken for each participant on their assessment date, including touchscreen questionnaires, verbal interviews, physical measurements, and biological sample assays. Additionally, the UK Biobank performs linkage to external hospital inpatient records, which include details on admission dates, diagnoses (including underlying conditions), procedures, and discharge information.

Outcome

We defined all aSAH cases between January 1, 1997, and October 31, 2022, using the hospital-based International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) code ‘430’ and 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes I60.0-I60.9. We specifically included codes I60.8 (“Other nontraumatic subarachnoid haemorrhage”) and I60.9 (“Nontraumatic subarachnoid haemorrhage, unspecified”) in our definition of aSAH because there is a high likelihood that these codes also include aSAH cases within the UK Biobank data. Typically, non-aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhages account for about 10–15% of all subarachnoid haemorrhage cases37. However, in the UK Biobank, codes I60.8 and I60.9 represent 59.4% of all subarachnoid haemorrhage cases, with 530 out of 893 cases, suggesting a probable inclusion of aSAH cases under these codes. Individuals diagnosed with aSAH before their assessment date were excluded from further analysis.

Predictors

We included all variables that were systematically assessed on the baseline assessment visit and available for at least 80% of the total cohort. This selection encompassed 618 variables, spanning categories such as patient characteristics (e.g., age, sex), sociodemographic factors (e.g., education, ethnicity), lifestyle factors (e.g., smoking status, diet), family and medical history, medication use, physical measurements (e.g., weight, blood pressure), blood assays, and environmental factors (e.g., noise and air pollution of residence area).

In the pre-processing of data, variables that allowed multiple responses from participants were converted into binary vectors, with each potential response encoded as a separate variable. For example, in response to the original question, “Vascular/heart problems diagnosed by a doctor,” participants could select from four options: heart attack, angina, stroke, and high blood pressure. Consequently, we created four distinct binary (yes/no) variables. For variables involving multiple same-day measures, such as systolic blood pressure, the values were averaged to create a single variable. In cases of highly correlated variables (absolute Pearson correlation greater than 0.90), we retained the variable with the fewest missing data points. We considered answers such as “Do not know” and “Prefer not to answer” as missing values. We refrained from removing outliers and instead relied on the outlier checks already implemented by the UK Biobank38. For instance, responses to “How many cups of tea do you drink each day?” indicating more than 99 per day were automatically excluded, while responses over 20 prompted verification from participants.

Based on the literature, we identified five established risk factors for aSAH: age at baseline, female sex, hypertension, smoking, and alcohol use5. Hypertension was defined as meeting one or more of the following criteria: an average systolic blood pressure over 140, diastolic blood pressure over 90, taking blood pressure medication, or having a doctor-diagnosed condition. Smoking status was categorised as ‘never,’ ‘previous,’ or ‘current.’ Alcohol consumption was categorised as ‘never,’ ‘rarely’ (defined as one to three times a month, or on special occasions), ‘often’ (defined as one to four times a week), and ‘daily.’

Statistical analysis

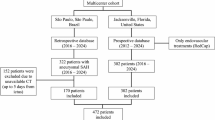

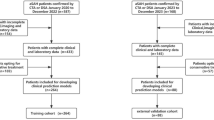

Our analysis consisted of two parts (Fig. 2). In the first part, we used a machine learning algorithm to identify potential risk factors for aSAH without predefined hypotheses. In the second part, we used logistic regression to examine and quantify these potential risk factors, while adjusting for established risk factors.

Machine learning algorithm

In the first part, we used the CatBoost machine learning algorithm to identify potential aSAH risk factors39. CatBoost is a gradient-boosting algorithm that operates on decision trees and is designed to process both numerical and categorical data without extensive pre-processing. A key advantage of CatBoost is its capability to automatically handle missing values without the need for imputation. We randomly divided the dataset into five equal-sized folds, each containing a similar proportion of aSAH cases. We trained a CatBoost model on four folds and reserved the fifth for validation. This cross-validation process was repeated until each fold served as the validation fold once, maximising the area under the curve (AUC) score for each validation fold. To assess variable importance, we calculated Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) values for each of the five models40. We then computed the average of the mean absolute SHAP values across the folds to identify the 25 variables with the highest mean absolute SHAP values. These variables represent the variables that had the greatest influence on the predicted probability of aSAH.

Traditional statistical model

In the second part, we used traditional statistical methods to further analyse the 25 variables with the highest mean absolute SHAP values, identified in the first part. We did not further analyse established risk factors when identified by the CatBoost model. We additionally removed variables with a variance inflation factor higher than 5 to account for multicollinearity. We addressed missing data by using multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) with five iterations and five imputed datasets41. We then visually examined the distribution of continuous variables and applied a logarithmic transformation to those variables that exhibited severe right-skewness. We proceeded to fit both univariable (unadjusted) logistic regression models and models adjusted for established risk factors to the imputed datasets. In the adjusted models, we designated “never” as the reference category for smoking status and “rarely” for alcohol use. We present differences in summary statistics for the established risk factors, using two-sample t-tests for numerical variables and chi-squared tests for the categorical variables. Finally, we presented the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), and p-values for each potential risk factor for aSAH by pooling the datasets and using Rubin’s rules42. We report the ORs as the increased aSAH risk associated with a 1 standard deviation increase of that variable to account for different variable scales. We additionally investigated interaction effects between the established aSAH risk factors and potentially novel aSAH risk factors. The machine learning model was developed in Python (version 3.13)43, using the packages pandas44, numpy45, catboost39, shap40, and scikit-learn46. The traditional statistical models were developed in R (version 4.4.0)47, using the ggplot248, dplyr49, and mice packages50.

Reporting standards

All results are reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines51.

The UK Biobank received ethics approval from the North West Multi-Center Research Ethics Committee (REC No. 16/NW/0274), and all participants provided written electronic informed consent.

Data availability

This research was conducted using the UK Biobank resource under application number 2532. The datasets are not publicly available but can be accessed via the UK Biobank data access process. More details are available at http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/register-apply/.

References

Macdonald, R. L. & Schweizer, T. A. Spontaneous subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet 389, 655–666 (2017).

GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 20, 795–820 (2021).

Johnston, S. C., Selvin, S. & Gress, D. R. The burden, trends, and demographics of mortality from subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurology 50, 1413–1418 (1998).

Etminan, N. & Rinkel, G. J. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: development, rupture and preventive management. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 12, 699–713 (2016).

Feigin, V. L. et al. Risk factors for subarachnoid hemorrhage: an updated systematic review of epidemiological studies. Stroke 36, 2773–2780 (2005).

Bakker, M. K. et al. Genetic risk score for intracranial aneurysms: prediction of subarachnoid hemorrhage and role in clinical heterogeneity. Stroke 54, 810–818 (2023).

Kanning, J. P. et al. Prediction of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in comparison with other stroke types using routine care data. PLOS ONE 19, e0303868 (2024).

Madakkatel, I., Zhou, A., McDonnell, M. D. & Hyppönen, E. Combining machine learning and conventional statistical approaches for risk factor discovery in a large cohort study. Sci. Rep. 11, 22997 (2021).

de la García, Á., Blanco, C., Olfson, M. & Wall, M. M. Identification of suicide attempt risk factors in a National US Survey using machine learning. JAMA Psychiatry. 78, 398–406 (2021).

Lee, K. S., Jha, N. & Kim, Y. J. Risk factor assessments of temporomandibular disorders via machine learning. Sci. Rep. 11, 19802 (2021).

Jordan, M. I. & Mitchell, T. M. Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science 349, 255–260 (2015).

Bi, Q., Goodman, K. E., Kaminsky, J. & Lessler, J. What is Machine Learning? A primer for the epidemiologist. Am. J. Epidemiol. 188, 2222–2239 (2019).

Breiman, L. & Statistical Modeling The two cultures (with comments and a rejoinder by the author). Stat. Sci. 16, 199–231 (2001).

Rudin, C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1, 206–215 (2019).

Breedveld, F. C., Bieger, R. & van Wermeskerken, R. K. A. The clinical significance of Macrocytosis. Acta Med. Scand. 209, 319–322 (1981).

Blundell, E. L. et al. Importance of low serum vitamin B12 and red cell folate concentrations in elderly hospital inpatients. J. Clin. Pathol. 38, 1179–1184 (1985).

Green, R. et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 3, 17040 (2017).

Zhang, C. et al. Tea consumption and risk of cardiovascular outcomes and total mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 30, 103–113 (2015).

Larsson, S. C. et al. Coffee and Tea Consumption and Risk of Stroke subtypes in male smokers. Stroke 39, 1681–1687 (2008).

Okamoto, K. Habitual green tea consumption and risk of an aneurysmal rupture subarachnoid hemorrhage: a case-control study in Nagoya, Japan. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 21, 367–371 (2006).

Mesas, A. E., Leon-Muñoz, L. M., Rodriguez-Artalejo, F. & Lopez-Garcia, E. The effect of coffee on blood pressure and cardiovascular disease in hypertensive individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 94, 1113–1126 (2011).

Söderholm, M., Zia, E., Hedblad, B. & Engström, G. Lung function as a risk factor for subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 43, 2598–2603 (2012).

Persson, C. et al. Peak expiratory flow and risk of cardiovascular disease and death. A 12-year follow-up of participants in the population study of women in Gothenburg, Sweden. Am. J. Epidemiol. 124, 942–948 (1986).

Cook, N. R. et al. Peak expiratory flow rate in an elderly population. Am. J. Epidemiol. 130, 66–78 (1989).

Lim, C. S., Kiriakidis, S., Sandison, A., Paleolog, E. M. & Davies, A. H. Hypoxia-inducible factor pathway and diseases of the vascular wall. J. Vasc Surg. 58, 219–230 (2013).

Knekt, P. et al. Risk factors for subarachnoid hemorrhage in a longitudinal population study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 44, 933–939 (1991).

Giller, C. A., Wills, M. J., Giller, A. M. & Samson, D. Distribution of hematocrit values after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Neuroimaging. 8, 169–170 (1998).

Feigin, V. et al. Smoking and elevated blood pressure are the most important risk factors for subarachnoid hemorrhage in the Asia-Pacific Region. Stroke 36, 1360–1365 (2005).

Hebert, P. R. et al. Height and incidence of cardiovascular disease in male physicians. Circulation 88, 1437–1443 (1993).

Banack, H. R. & Kaufman, J. S. Does selection bias explain the obesity paradox among individuals with cardiovascular disease? Ann. Epidemiol. 25, 342–349 (2015).

Mhurchu, C. N. et al. Hormonal factors and risk of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: an international population-based, case-control study. Stroke 32, 606–612 (2001).

Larsson, S. C., Wallin, A., Wolk, A. & Markus, H. S. Differing association of alcohol consumption with different stroke types: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 14, 178 (2016).

Madsen, C. et al. Association between tobacco smoke exposure and levels of C-reactive protein in the Oslo II study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 22, 311–317 (2007).

Vabalas, A., Gowen, E., Poliakoff, E. & Casson, A. J. Machine learning algorithm validation with a limited sample size. PLOS ONE. 14, e0224365 (2019).

Fry, A. et al. Comparison of Sociodemographic and Health-related characteristics of UK Biobank participants with those of the General Population. Am. J. Epidemiol. 186, 1026–1034 (2017).

Sudlow, C. et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 12, e1001779 (2015).

Claassen, J. & Park, S. Spontaneous subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet 400, 846–862 (2022).

Resource 113241. https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/ukb/refer.cgi?id=113241

Prokhorenkova, L., Gusev, G., Vorobev, A., Dorogush, A. V. & Gulin, A. CatBoost: unbiased boosting with categorical features. Preprint at. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1706.09516 (2019).

Lundberg, S. & Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1705.07874 (2017).

Azur, M. J., Stuart, E. A., Frangakis, C. & Leaf, P. J. Multiple imputation by chained equations: what is it and how does it work? Int. J. Methods Psychiatr Res. 20, 40–49 (2011).

Rubin, D. B. Estimating Causal effects from large data sets using propensity scores. Ann. Intern. Med. 127, 757–763 (1997).

The Python Language Reference. Python documentation https://docs.python.org/3/reference/index.html

API reference. — pandas 2.2.2 documentation. https://pandas.pydata.org/docs/reference/index.html

NumPy Documentation. https://numpy.org/doc/

Scikit-learn. machine learning in Python — scikit-learn 1.5.0 documentation. https://scikit-learn.org/stable/

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Available at https://www.R-project.org/ (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2024).

Wickham, H. et al. ggplot2: Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics. (2024).

Wickham, H. et al. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. (2023).

van Buuren, S. et al. mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations. (2023).

von Elm, E. et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 335, 806–808 (2007).

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement No. 852173).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualisation and design of the research. YR conducted the data acquisition. JPK conducted the analyses. All authors contributed to data interpretation. JPK wrote the manuscript. All authors were involved in editing the manuscript. All authors are accountable for their contribution, in addition to all aspects of the manuscript. All authors have approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kanning, J.P., Wang, J., Abtahi, S. et al. Identifying novel risk factors for aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage using machine learning. Sci Rep 15, 9256 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88826-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88826-3