Abstract

Simulating virtual crowds can bring significant economic benefits to various applications, such as film and television special effects, evacuation planning, and rescue operations. However, the key challenge in crowd simulation is ensuring efficient and reliable autonomous navigation for numerous agents within virtual environments. In recent years, deep reinforcement learning has been used to model agents’ steering strategies, including marching and obstacle avoidance. However, most studies have focused on simple, homogeneous scenarios (e.g., intersections, corridors with basic obstacles), making it difficult to generalize the results to more complex settings. In this study, we introduce a new crowd simulation approach that combines deep reinforcement learning with anisotropic fields. This method gives agents global prior knowledge of the high complexity of their environment, allowing them to achieve impressive motion navigation results in complex scenarios without the need to repeatedly compute global path information. Additionally, we propose a novel parameterized method for constructing crowd simulation environments and evaluating simulation performance. Through evaluations across three different scenario levels, our proposed method exhibits significantly enhanced efficiency and efficacy compared to the latest methodologies. Our code is available at https://github.com/tomblack2014/DRL_Crowd_Simulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The meta-universe era is upon us, and the construction of highly immersive virtual worlds based on computer simulation is a pivotal frontier technology being explored by both industry and academia. One of the core issues that needs to be resolved is the autonomous navigation of a large number of agents within these simulated environments. Decades of research have shown that to achieve exceptional agent simulation, agents must be modeled in a multidimensional and multilayered manner, including individuals, groups, physics, psychology, and more1,2. These various levels are often intricately interconnected. Steering, which includes obstacle avoidance and target searching based on environmental awareness, is a crucial aspect of agent behavior. Therefore, an efficient, seamless, and resilient steering implementation is essential to achieve high-quality agent simulation.

Crowd simulation has been a topic of research for nearly three decades3,4. Early efforts focused on manually crafted mathematical models, such as patch-based5, vision-based6, force-based7, and velocity-based8 approaches. These methods are structurally simple and easy to implement, forming the basis of current industrial crowd simulation software. The data-driven paradigm9 introduces a new concept of motion generation that relies on data sources. By extracting characteristics of pedestrian behavior from raw video data, it enables agents to simulate accordingly. While these classical methods have had a significant impact on the application landscape, their results often suffer from limitations in terms of rigidity, homogeneity, and efficiency.

Reinforcement learning is well suited for crowd simulation10 due to its design, which includes components such as the environment, agent perception, agent action, and action reward. In recent years, many studies11,12,13 have focused on enabling autonomous navigation of agents in virtual environments by training neural networks to adapt to the agents’ actions or value strategies. However, several challenges remain: 1.The simulation environment’s structure is often simplistic and uniform, leading to a lack of diversity in the behavior patterns of trained agents. 2.In existing methods, reinforcement learning primarily relies on local environment information as input perception. Agents require additional global information during decision-making, which results in significant computational overhead, and and hinders the implementation of end-to-end systems. 3.There is a lack of agent performance evaluation metrics that are grounded in multi-level virtual environments.

We propose a novel deep reinforcement learning method for crowd simulation, based on the anisotropic field(AF) framework previously introduced by predecessors14. Furthermore, we present a parametric approach to constructing virtual environments for crowd navigation, capable of generating a wide range of plausible and heterogeneous scenarios for agents to explore. During training, we incorporate the desired speed into the state space, achieving fine-grained control over the agent’s speed and enabling variable-speed movement in the simulation. Moreover, since the AFs are positioned within the environment and implicitly include scene navigation information, the agent can effectively complete steering tasks with similar efficacy, eliminating the need for global path planning (GPP). This innovation significantly enhances the mobility efficiency of the crowd simulation system. Our contributions are three-fold:

-

We present a parameterized methodology for constructing crowd navigation environments. Through the manipulation of a few key parameters, we efficiently generate a multitude of crowd navigation environments, varying in complexity, obstacle distribution, and other characteristics. This provides valuable training and evaluation metrics for crowd simulation, thereby enhancing the generalization capability of simulated crowd generation.

-

We introduce an efficient and adaptable crowd navigation approach based on deep reinforcement learning, showcasing broad applicability across diverse multi-class scenarios. By introducing AF into the state space of reinforcement learning, we eliminate the requirement for GPP in intricate navigation environments, thereby markedly decreasing computational expenses and enhancing the ease of constructing and maintaining end-to-end systems. Consequently, reinforcement learning-trained agents can produce accurate and varied steering outcomes.

-

By incorporating the desired speed into the state space and devising an appropriate reward function, we establish an adaptive mechanism for configuring and adjusting the agents’ speeds during simulation. This enables agents to dynamically control their behavioral patterns, facilitating the heterogeneous generation of crowds.

Related work

Crowd simulation, as an integral branch of computer graphics and artificial intelligence, has received significant attention in recent years. Researchers in this field strive to replicate the behaviors, dynamic interactions, and flow patterns of real-world crowds, aiming to create highly realistic animation effects and gain a deeper understanding and prediction of complex social phenomena. Over the past few decades, crowd simulation has evolved from the classical study of flocking behavior15 to a multi-level, multi-granular approach that encompasses the understanding and simulation of large-scale group dynamics1,2,3,4. The main focus of this paper is on implementing high-quality crowd simulation using reinforcement learning, as well as generating and assessing various virtual simulation scenarios.

Classic agent-based crowd simulation

Agents serve as the fundamental building blocks of a virtual crowd. During the simulation process, these agents require continuous behavior generation based on an autonomous decision-making system that utilizes the environmental information they possess. Over the past few decades, several classical methods focused on agent implementation have emerged in the field of crowd simulation. The classical Social Force Model (SFM), which is rooted in Newtonian mechanics, employs attraction and repulsion to reflect the behavioral motivations of pedestrians7,16,17. Subsequently, the extended force-based model was widely used to depict agents navigating complex environments with a large number of participants (such as evacuations, formations, interactions, etc.). However, despite its simplicity and ease of implementation, the force-based model’s reliance on numerous parameter experiments to balance various forces often leads to distorted or erroneous agent behavior due to force imbalances.

On the other hand, the velocity-based approach coordinates the positions and velocity directions of all agents. It ensures collision avoidance during motion by prompting interacting agents to yield to each other in the direction of their respective velocities. Early versions of this model, such as Reciprocal Velocity Obstacles (RVO), and their refined counterparts like Optimal Reciprocal Collision Avoidance (ORCA), have gained significant influence in industrial applications, particularly in game engines8,18. Compared to the force model, the velocity-based method performs better with longer time steps. The classical methods serve as important baselines for comparing the methodology presented in this study during the subsequent experiments.

Crowd simulation by machine learning

Addressing the challenge of crowd steering through artificial modeling leads to a rapid increase in both the number and diversity of parameters, making them incompatible19. Generally, a steering model designed to address a specific problem struggles to maintain optimal performance in different environments20. As the number of parameters multiplies to correct errors, the issue of parameter explosion becomes more severe. The crowd steering problem is a complex, high-dimensional, semi-chaotic, open-loop system11, which inherently makes it difficult to solve through manual modeling and continuous parameter tuning.

Over the past decade, machine learning techniques, particularly those based on deep neural networks, have introduced numerous innovative approaches to address this dilemma. One prominent solution involves learning from crowd trajectory data, thereby reformulating the crowd steering problem as a trajectory prediction task21. This approach frames agent steering as localized trajectory forecasting, where future trajectories are inferred based on the agent’s position, target point, and current state. A seminal implementation of this strategy used Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks to predict human trajectories in dense settings22, and subsequent works have continually refined the methodology. GANs have been utilized to generate diverse predictive scenarios23,24, while variational recurrent neural networks have been employed to accelerate convergence25,26,27.

However, a fundamental limitation persists in these trajectory-learning-based approaches. Specifically, the accuracy of trajectory predictions heavily depends on the training dataset, and the complexity of crowd dynamics exceeds the representational capacity of limited trajectory data. An alternative perspective, advocated and employed in this study, is to address the crowd steering problem through reinforcement learning28. Reinforcement learning explores the state space that an agent may encounter during its actions, optimizing behavioral strategies based on environmental rewards. This approach is particularly suited for solving large-scale crowd steering challenges in complex environments29,30. Early efforts in reinforcement learning, focusing on simple discrete spaces, successfully demonstrated navigation capabilities for small groups31,32,33. Subsequently, deep reinforcement learning, powered by deep neural networks, gained widespread adoption in crowd steering due to its superior ability to model high-dimensional continuous state spaces, leading to groundbreaking contributions10. Xu et al.34 combined deep reinforcement learning with ORCA, improving agents’ motion efficiency and fluidity. Hu et al.11 introduced a model-free approach to learn a parameter strategy, generating heterogeneous synthetic populations, which achieved competitive performance with traditional methods while maintaining favorable computational efficiency.

Crowd simulation performance quantification

The foundation for quantifying the performance of crowd simulation relies on having a precise definition of the objective of the crowd simulation task. Computer simulations of crowd behavior may prioritize different performance indicators, depending on the specific goals of the application. For example, some studies12,35,36 aim to simulate a virtual crowd system that closely mirrors real crowds. By doing so, they can uncover the operational rules of real crowds and identify potential risks within the system. As a result, their quantitative performance metrics focus on the authenticity of the simulation results, the similarity to real crowd systems, and the behavior of individual agents.

This type of work is often presented in three-dimensional scenes with strong modeling foundations, providing users with an immersive visual experience. On the other hand, some studies aim to achieve smooth and visually appealing group movements37,38,39, with less emphasis on authenticity. These efforts tend to focus on the organizational structure of crowds and the consistency of movement flows. When quantifying performance for these tasks, the primary focus is on group coherence, the accuracy of visual representation, and maintaining boundaries. This type of work is primarily used in film and television special effects, performance rehearsals, and similar applications, where the goal is to simulate individuals with unique characteristics under tight constraints.

A significant amount of research focuses on improving and evaluating the performance of steering itself, which includes waypoint reaching, obstacle avoidance, and emergent behaviors in various and complex scenarios40. A classic example of this is measuring the evacuation efficiency of different algorithms in crowd evacuation situations17, where factors such as collision avoidance, movement distance, and total evacuation time are assessed. These methods, which utilize automatically or semi-automatically generated virtual scenes, have been rigorously tested with classical algorithms41. However, one ongoing challenge is the limited complexity and diversity of environmental construction. The parametric approach to constructing crowd turning environments proposed in this study introduces a new virtual scene construction algorithm, along with accompanying source code, providing an effective way to quantify performance for future methodologies.

Methods

In this section, we introduce the definition and generation method of virtual environments related to the crowd simulation problem. Additionally, we provide the details of proposed crowd simulation method based on deep reinforcement learning.

Generating crowd simulation environment

Creatures or robots in the real world explore their environment through senses such as vision and hearing. Similarly, agents use perceptrons to perceive the virtual environment around them and complete tasks based on that information. Unlike the complexity of setting up a scene in the real world, a large number of virtual environments could be generated quickly using algorithms. To standardize the description, the environment is defined as a two-dimensional square space with a specified width w and height h. The principles outlined in this study can also be applied to navigation problems in higher dimensions. The entire environment is rasterized into a grid to form its structure. Each grid cell within this environment can be in either an “accessible” or “inaccessible” state, where “accessible” indicates that it is free to move through, and “inaccessible” indicates that it is blocked by an obstacle. In this way, a virtual environment can be efficiently stored in minimal memory space using bitsets.

For an environment of a certain size (w, h), there are \(2^{wh}\) possible heterogeneities. In order for an agent to perform tasks in a virtual environment correctly and efficiently in theory, the environment needs to be solvable, meaning that all ‘on’ areas within the environment must be connected. Based on the definitions provided earlier, parameters P can be defined to characterize a class of environments.

Here, \(s=(w,h)\) represents the size of the environment. w represents the width of the environment, and h represents the height of the environment. \(os=(o_{min},o_{max})\) denotes the size range of the independent obstacle sizes within the scene. \(o_{min}\) represents the minimum value of the obstacle’s side length, and \(o_{max}\) represents the maximum value of the obstacle’s side length. The sizes of all obstacles in the scene are restricted to fall within this range. \(\zeta\) signifies the proportion of the total area covered by obstacles in the scene. Meanwhile, \(\eta\) represents the proportion of obstacles indicating independence relative to the total number of obstacles. Both \(\zeta\) and \(\eta\) values lie between 0 and 1. Parameters P can be used to broadly refer to the properties of a class of environments, and given these parameters, Algorithm 1 can automatically generate the corresponding environment.

In the aforementioned algorithm, \(single_{off}\) represents the proportion of obstacles with no other obstacles in their neighborhood, and \(nsingle_{off}\) represents the proportion of obstacles that are part of a connected domain. The algorithm guarantees that the result environment can be solved while also adhering to the constraints placed on the parameters, which affect the characteristics of the generated results. Figure 1 shows the different styles of generation outcomes that can be achieved with various parameter settings. Utilizing deep reinforcement learning to train and evaluate the performance of agents in a complex and highly differentiated virtual environment provides numerous advantages, particularly in terms of improving the agents’ ability to navigate and make decisions within the environment.

Like most existing work, our agent is depicted as a two-dimensional disk with an orientation denoted by \(({\textbf {o}},\theta )\). Here, \({\textbf {o}}\) represents the location of the agent, while \(\theta\) represents its orientation. At the start of each time step, the agent makes a decision in the form of an acceleration \({\textbf {a}}\). This decision is then used to update the agent’s speed and heading, a process that is implemented using the classical Euler integral model42.

Here, \(\omega _{max}\) represents the maximum angular velocity that the agent can achieve within one step \(\Delta t\). \({\textbf {v}}\) denotes the agent’s instantaneous velocity. The formula does not specify the direction of rotation (clockwise or counterclockwise). During the calculation process, it is important to determine and choose the rotation direction that yields the smallest angle. c is the damping coefficient that accounts for factors such as friction and air resistance affecting the agent’s motion in the environment. From this, it can be easily inferred that there is an upper speed limit for the agent in this model, denoted as \(v_{lim}=\sqrt{\frac{a_{max}}{c}}\), where \(a_{max}\) is the constant representing the maximum acceleration limit.

Each agent’s task within the environment involves navigating from a starting point in one open area to a target point in another. As previously mentioned, all open areas are interconnected, guaranteeing that all tasks have viable solutions. By utilizing various steering algorithms, multiple agents can perform their tasks simultaneously in a periodic manner. The performance of the algorithm is evaluated by quantifying the results achieved.

Reinforcement learning

Solving agent steering through reinforcement learning requires assuming the process of an agent performing a task in the environment follows a Markov process. This process is formally defined using a Markov Decision Process (MDP)43, which is represented as a five-tuple \((S,A,T,R,\gamma )\), along with the introduction of a policy \(\pi\). Here, S and A represent the sets of all possible states and actions of the agent, respectively, forming the state space and action space. \(T(s^{\prime }|s,a)\) denotes the probability of transitioning from state s to state \(s^{\prime }\) through action a. R is the reward function associated with state transitions. \(\gamma \in (0,1)\) is a discount factor that adjusts the weight of future potential rewards. Reinforcement learning aims to optimizing a policy \(\pi (a|s,\theta )\) to maximize the expected cumulative reward \(U_k\). This is achieved by finding the best policy that maps states to actions, given the current state and the parameters \(\theta\) of the policy.

To achieve the goal, we fit the mapping relationship between states and actions using a machine learning model. This model should be capable of maximizing the cumulative reward obtained from a series of actions, empowering the agent with the intelligence needed to perform tasks accurately within the environment. Specifically, we have chosen to employ the Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (TD3) algorithm44 to fit the policy function and generate optimal actions. The TD3 algorithm was selected due to its robustness in handling continuous action spaces and its ability to mitigate overestimation biases commonly encountered in deep reinforcement learning. The Actor-Critic architecture45 is utilized to iteratively learn both the optimal action strategy (provided by the Actor) and the optimal action value estimation (provided by the Critic). Furthermore, we combine this with the Target Network, which helps stabilize the learning process. To optimize network parameters, we apply Clipped Double-Q Learning46, which helps prevent overestimation of action values, and smoothing of the target policy, which helps improve the robustness of the learned policy.

Anisotropic fields

The anisotropic field (AF) is a newly introduced simulation model specifically designed for crowd navigation. Its purpose is to encapsulate the complexities of crowd dynamics14. The core concept of AF revolves around fitting the various behavioral patterns exhibited by crowds within an environment by applying superimposed probability distributions. Figure 2 illustrates the properties of AFs, as well as a comparison with classical navigation fields47. Compared to the classic navigation fields model, AF stands out as it has the potential to drive crowd simulations towards more diverse and heterogeneous behavior patterns.

In the context of working with AFs, researchers have discovered a crucial aspect: AF inherently captures both the obstacles present in the environment and the overall behavioral trends of agents within it. A key innovation in our research lies in the introduction of anisotropic fields at some critical locations in the environment, serving as prior knowledge for the agent in navigating the randomly generated unknown environment. This approach helps the agent make more intelligent and rational behavioral decisions without the need for global path searching.

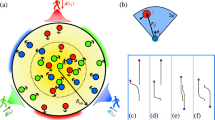

An approximation of global navigation information for the agent is derived from the AF at key locations. (a) illustrates the process of obtaining the AF through trajectory sampling. (b) depicts the screening of its critical components using Eq. (7). For instance, the green portion. (Searching for activation functions) demonstrates how global navigation can be achieved, transcending local optimization, based on the filtered AF.

In contrast to the original paper14 which generates AFs through video analysis or drawing lines, we employ a novel approach where trajectories serve as the foundation for AF generation. This is accomplished by conducting a large number of random global navigations within the scene. As illustrated in Fig. 3, multiple random A* global navigations were executed within a 10m × 10m scene, resulting in an equivalent number of paths.

To generate AFs within the environment based on these trajectories, we adopt the methodology outlined in the original paper14. However, due to the highly discrete distribution of most AFs generated through this method, extracting meaningful information from them becomes challenging. Therefore, the effective AFs is selected using the following formula

Here, \(\Omega _{AF}\) represents the set of all AFs in the environment. \(\overline{p}\) denotes the expectation of P(G), where P(G) is a probability distribution related to the environment.The number of terms obtained after discretizing P(G) is denoted as n, and \(\delta\) is a threshold constant. As illustrated in Fig. 3, it is evident that the selected AFs are primarily located near the obstacles. This positioning enables them to better capture the characteristics of the surrounding environment. Consequently, these AFs provide agents with valuable potential information during navigation.

State & action space

To ensure that the agent performs the task accurately and efficiently within the virtual environment using deep reinforcement learning, it is crucial to standardize both the state space and the action space of the agent. The state space includes all the information gathered through the agent’s observation of the environment. In the context of this study, for the agent to successfully complete the task, it must navigate to the destination while avoiding any obstacles. Therefore, the following state space is defined to provide the agent with sufficient information to achieve these objectives

Figure 4 illustrates the details of state space. Here, \({\textbf {d}}_{tgt}=(d_x,d_y)\) is the relative positional relationship between the agent’s current position and the target position. The agent’s current speed is denoted by \({\textbf {v}}=(v_x,v_y)\). \({\textbf {V}}_E\) is a scalar that signifies the expected speed of the artificially set agent during motion. This value can be adjusted freely during the simulation system’s runtime, allowing the agent to dynamically change its expected speed. The agent probes the environment ahead using depth rays, and \(\varvec{\Theta }\) signifies the distance to the nearest obstacle in various directions. Based on historical experience and comparative analysis, the interval between detection rays is set to 15°. \({\textbf {d}}_{af}\) represents the AF at the agent’s current location. Occasionally, when the agent moves to a position where the AF is not distributed, the default value remains constant.

The action space encompasses all the behaviors that the agent can exhibit within its environment. Consistent with the definition of the agent’s behavior in a simulated environment, we focus solely on acceleration, denoted as \({\textbf {a}}=(a_x,a_y)\).

Reward function

Well-designed reward mechanisms can greatly enhance an agent’s ability to learn how to perform tasks accurately and efficiently within its environment. Building on prior research11,30, the reward design framework is based on the principles of penalizing collisions and rewarding task completion. However, what sets the approach apart is how to tackle the challenge of achieving convergence in complex environments, where sparse rewards and penalties are encountered during exploration learning. The reward structure is defined as

Here, \(r_{arrv}\) represent the reward acquired by the agent for completing a task and \(p_{move}\) represent the penalty imposed for each action taken during a clock cycle within a task, both of which are constants. \(r_close\) denotes the immediate reward given to the agent for moving closer to the target point. \(d_{last}\) and \(d_{cur}\) represent the distances between the agent and the target point in the previous and current clock cycle, respectively. To encourage the agent to exhibit more intelligent behaviors, such as detouring around obstacles, no penalty is imposed on the agent when it is far away from the intended target. This is based on empirical evidence. \(p_{coll}\) represents the penalty imposed on the agent for colliding obstacles or other agents, where r is the radius of the agent. \(p_{speed}\) is the penalty introduced for deviations between the current speed and the expected speed. \(w_1\), \(w_2\), \(w_3\) and \(w_4\) are all constant coefficients that are used to adjust the weight of each reward or penalty component in the overall reward function.

Training

We randomly generate a series of 100 m × 100 m training environments. The smallest obstacle cell size is 2 m × 2 m. During the training process, all agents share the same network parameters, but they are each given unique, randomly assigned objectives. Because AF naturally contains a potential expression of obstacle information, the calculation of the global path between the agent and the target is avoided. This approach helps to conserve computational resources during both training and running.

To tackle the issue of reward sparsity, we use curriculum learning to gradually improve the agent’s strategy. The level of environment is mainly adjusted by changing the value of \(\zeta\) or the number of agents \(n_a\). From simpler to more complex scenarios, the \(\zeta\) increases from 0 to 0.15, and the \(n_a\) involved rises from 1 to 50. Specifically, whenever the \(\zeta\) increases by 0.02, the \(n_a\) increases by 10. Once the \(\zeta\) reaches 0.1, the \(n_a\) remains constant at 50 thereafter. Compared to the state-of-the-art work11, our training includes a wider range of environmental samples, which allows the trained agent to demonstrate a more generalized behavior.

In our network architecture, both the Actor and Critic components have two fully connected hidden layers, each with 1024 artificial neurons. The number of neurons in our network was determined based on the task scale and the memory of the computer GPU. The Actor uses the tanh activation function between layers, while the Critic uses the relu activation function44,48. During training, we use the Adam optimizer to update the network parameters49. The specific training hyperparameters are listed in Table 1. Each episode of simulation in the training is triggered either when all agents complete their goals or 8000 training steps have been reached. For specific details, you can also refer to our Github code repository.

Experiments

In this section, we present the quantitative performance metrics and methods used for crowd navigation in this study. We also provide a multi-dimensional comparison between the proposed method and other works, based on these metrics.

Quantification method

The crowd simulation in this study is defined as a scenario involving a finite number of agents continuously navigating within a connected environment. Inspired by previous works11,41, we used five metrics to evaluate the performance of the agents during task execution, highlighting the advantages of our approach: (a) Calculation Cost, (b) Collision, (c) Timeout, (d) Completion Time, and (e) Velocity Variance. Specifically, (a) refers to the average computation time required by each agent to complete a task. (b) and (c), are metrics of errors encountered by agents during task execution. They include collisions between agents or with obstacles, as well as timeouts resulting from inaccurate movements. (d) assesses the average efficiency of task execution. If timeout happened, the result will be calculated based on the maximum allowed time and are factored into this metric as a penalty. Note that the time referenced here is the simulation environment’s elapsed time, whereas (a) refers to real-world computation time. Lastly, (e) measures the deviation of an agent’s speed from its expected speed during simulation. It serves as a metric of movement smoothness and the cumulative error in expected speed during task execution.

To demonstrate the generalization of the model, we used experimental environments that differs from the training environment. In each experimental setting, we deployed \(n_a\) agents, with each agent sequentially completing \(n_t\) tasks. In this paper, \(n_t=3000\). Upon completing a task, the agent’s current position becomes the starting point for the next task, and motion is executed towards the new destination. If a task results in a timeout, the agent is randomly reassigned a new departure location, and a new set of tasks is generated. The parameters \(n_a\) and \(\zeta\) significantly influence the execution efficiency and completion rate of agent tasks. In this study, we examined the correlation between these parameters and factors such as collisions, timeouts, and completion times. As shown in Fig. 5, as the number of obstacles and agents in the environment increases, the three indicators (collisions, timeouts, and completion times) rise markedly, indicating a decrease in the average efficiency and quality of the tasks executed by the agents.

Based on this experimental setup,the environments was categorized into three levels: Easy, Middle, and Hard (Fig. 6). The training environments and test environments had both five, which were totally different with each other. The results reported are the average of the outcomes from the five test environments. The correlation between the levels and the environmental parameters is presented in Table 2.

Comparisons

In this section, we assess the performance of the proposed model by comparing it to a seminal work7 and a state-of-the-art (SOTA) work that utilizes deep reinforcement learning11. For each approach, two versions were present: one with GPP and one without. the agent’s long-term path updated every 2 seconds and conduct thousands of navigation tasks in the test environment. We evaluated all works based on various aspects, including performance and computational efficiency.

Table 3 demonstrates that our approach has successfully improved crowd navigation performance, particularly through the introduction of AF for alternative optimization of GPP. Additionally, the computational cost significantly reduced, while the navigation performance either matchs or exceeds the current optimal method. This improvement is due to resolving local deadlocks caused by concavities in complex environments11, which is especially noticeable in more challenging navigation tasks with a higher number of agents and obstacles. Figure 7 illustrates the details of local deadlocks.

Comparison between the proposed work and SOTA work11 in the hard level. Red boxes represent the agents stuck in the environment and can not finish the tasks.

Ablation experiment

A key innovation of this work is the introduction of masked AFs at critical locations within the environment. These fields were incorporated into the state space of the deep reinforcement learning agent model, providing the agent with prior knowledge of global navigation information in complex environments. Furthermore, by including a desired velocity in both the state space and the reward function, the agent is able to learn how to regulate its own movement. In this section, we examined the necessity of these two core designs through ablation experiments. Specifically, in the withour AFs case, the AFs was removed from the scene and concurrently eliminate the corresponding fields from the agent’s state space. Similarly, in the without expected speed case, the desired speed was removed from the state space and the speed reward was removed from the reward function.

The performance results of the aforementioned versions are shown in Table 4. The removal of any component results in a decrease in either partial or overall performance, highlighting the effectiveness of each design element. Most notably, a significant decline in performance, along with an increase in velocity variance, is observed when the AFs are omitted. This underscores the positive impact of the AF on navigation results. In the experiment where the expected speed was removed, the agent exhibited confusion and repetition in its speed regulation during task execution due to the lack of a clear directive to achieve smooth target speed control. This resulted in a notable increase in the velocity variance index.

The performance of this work under two scenarios: the hallway (top, featuring a narrow middle section) and the crossroads (bottom). In both scenarios, we predetermine the expected velocity distribution of the agents using the average distribution and the normal distribution, respectively. The velocity distribution observed in the actual simulation results closely matches the predefined expectations.

Motion control based on expected speed

Our work can also be easily adapted to classic crowd simulation scenarios, such as corridor crossing and intersections. As shown in Fig. 8, we preconfigured a sampling model for the expected speed of agents in the scene, utilizing separate bases: an average distribution and a normal distribution. After multiple simulation iterations, the probability distribution model of the actual speeds of the agents within the scene closely matches the normal distribution of the expected speeds. This indicates that the proposed model is able to effectively control the speeds of the agents, which is beneficial for generating heterogeneous crowds in crowd simulations.

Furthermore, both sets of experiments have exhibited impressive results in replicating classic scenarios. When agents have not entered the central convergence area, agents within the same region exhibit relatively consistent movement behavior. In the central merging zone, each agent, while completing its own motion navigation tasks (approaching the target and avoiding obstacles), also strives to maintain its speed close to the expected speed. In Fig. 8, this is manifested as varying trajectory lengths among the agents, as the trajectories document the connections of the agents’ historical positions within the same clock cycle period. By setting a velocity distribution for the crowd to achieve varied movements among the agents, the simulated collective demonstrates a resemblance to real crowds.

Comparison of simulated and real-world crowd dynamics

In this section, we have constructed simulation scenarios based on scenes derived from crowd datasets in the real world50. Within these scenarios, agents are placed with a distribution similar to that in the real datasets, and simulations are performed accordingly. Figure 9 illustrates the relationship between the simulation results and the real data, indicating that the method presented in this paper is capable of generating behavioral trajectories that resemble those of real crowds.

The performance of this work under two scenarios from ETH dataset50. To enhance the effect, the simulation scenario has been adjusted by slightly increasing the number of agents.

Discussion & limitations

Simulating crowds is a complex task that involves multiple individuals and intricate connections. Capturing the unique and heterogeneous behavior patterns among agents can be challenging for crowd simulation designers, as it requires the intricate adjustment of numerous parameters, which can be time-consuming and requires expertise. The integration of machine learning, particularly deep reinforcement learning, offers a promising solution to alleviate this burden.

In this study, we present an efficient and adaptable method for crowd navigation using deep reinforcement learning. By incorporating anisotropic field into the state space, we streamline the algorithm flow by replacing the traditional GPP approach, enhancing its overall efficiency. Furthermore, by embedding the desired speed within the state space and designing an appropriate reward function, we achieve flexible configuration and adjustment of agent speeds during simulations, allowing for the emergence of behavior patterns. The effectiveness of our approach is supported by extensive simulation experiments conducted across various virtual environments generated through parameterization.

While the proposed work primarily focuses on efficience in task content and speed control during movement, the real-world complexities of crowd behavior extend beyond these factors. Real-world crowds are influenced by a myriad of factors such as psychology, sound, smell, interpersonal interactions, and remote communication. Therefore, in the future work, we plan to explore the nuances of crowd simulation deduction under multimodal information, grounded in the analysis of real-world crowd data. Our goal is to bridge the gap between virtual and real-world crowds.

Data availability

The source code and environment data for this study are available on GitHub at https://github.com/tomblack2014/DRL_Crowd_Simulation.

References

Lemonari, M. et al. Authoring virtual crowds: A survey. Comput. Graph. Forum 41, 677–701. https://doi.org/10.1111/cgf.14506 (2022).

Yang, S., Li, T., Gong, X., Peng, B. & Hu, J. A review on crowd simulation and modeling. Graph. Models 111, 101081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gmod.2020.101081 (2020).

van Toll, W. & PettrÃ, J. Algorithms for microscopic crowd simulation: Advancements in the 2010s. Comput. Graph. Forum 40, 731–754. https://doi.org/10.1111/cgf.142664 (2021).

Musse, S. R., Cassol, V. J. & Thalmann, D. A history of crowd simulation: The past, evolution, and new perspectives. Vis. Comput. 37, 3077–3092 (2021).

Yersin, B., Maïm, J., Pettré, J., Thalmann, D. Crowd patches: Populating large-scale virtual environments for real-time applications. In Proceedings of the 2009 Symposium on Interactive 3D Graphics and Games, I3D ’09, 207–214, https://doi.org/10.1145/1507149.1507184 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2009).

Ondřej, J., Pettré, J., Olivier, A.-H. & Donikian, S. A synthetic-vision based steering approach for crowd simulation. ACM Trans. Graph. 29, 1778860. https://doi.org/10.1145/1778765.1778860 (2010).

Helbing, D. & Molnar, P. Social force model for pedestrian dynamics. Phys. Rev. 51(5), 4282–4286 (1995).

van den Berg, J., Lin, M., Manocha, D. Reciprocal velocity obstacles for real-time multi-agent navigation. In 2008 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 1928–1935. https://doi.org/10.1109/ROBOT.2008.4543489 (2008).

Lerner, A., Chrysanthou, Y. & Lischinski, D. Crowds by example. Comput. Graph. Forum 26, 655–664. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8659.2007.01089.x (2007).

Lee, J., Won, J., Lee, J. Crowd simulation by deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 11th ACM SIGGRAPH Conference on Motion, Interaction and Games, MIG ’18, https://doi.org/10.1145/3274247.3274510 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2018).

Hu, K. et al. Heterogeneous crowd simulation using parametric reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 29, 2036–2052. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVCG.2021.3139031 (2023).

Rempe, D. et al. Trace and pace: Controllable pedestrian animation via guided trajectory diffusion. In IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (2023). https://arxiv.org/2304.01893.

Charalambous, P., Pettre, J., Vassiliades, V., Chrysanthou, Y. & Pelechano, N. Greil-crowds: Crowd simulation with deep reinforcement learning and examples. ACM Trans. Graph. 42, 359. https://doi.org/10.1145/3592459 (2023).

Li, Y., Liu, J., Guan, X., Hou, H. & Huang, T. Introducing anisotropic fields for enhanced diversity in crowd simulation. Arxiv. https://arxiv.org/2409.15831 (2024).

Reynolds, C.W. Flocks, herds and schools: A distributed behavioral model. In Proceedings of the 14th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, SIGGRAPH ’87, 25–34, https://doi.org/10.1145/37401.37406 (Association for Computing Machinery, 1987).

Karamouzas, I., Heil, P., van Beek, P. & Overmars, M. H. A predictive collision avoidance model for pedestrian simulation. In Motion in Games (eds Egges, A. et al.) 41–52 (Springer, 2009).

Helbing, D., Farkas, I. & Vicsek, T. Simulating dynamical features of escape panic. Nature 407, 487–490. https://doi.org/10.1038/35035023 (2000).

van den Berg, J., Guy, S. J., Lin, M. & Manocha, D. Reciprocal n-body collision avoidance. In Robotics Research (eds Pradalier, C. et al.) 3–19 (Springer, 2011).

Yan, D. et al. Enhanced crowd dynamics simulation with deep learning and improved social force model. Electronics 2079–9292, 13 (2024).

Yan, D., Ding, G., Huang, K. Huang, T. Generating natural pedestrian crowds by learning real crowd trajectories through a transformer-based gan. The Visual Computer (2024).

Cheng, Q., Duan, Z. & Gu, X. Data-driven and collision-free hybrid crowd simulation model for real scenario. In Neural Information Processing (eds Cheng, L. et al.) 62–73 (Springer, 2018).

Alahi, A. et al. Social lstm: Human trajectory prediction in crowded spaces. In 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 961–971, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.110 (2016).

Gupta, A., Johnson, J., Fei-Fei, L., Savarese, S. & Alahi, A. Social gan: Socially acceptable trajectories with generative adversarial networks. In 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2255–2264, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2018.00240 (IEEE Computer Society, 2018).

Amirian, J., Hayet, J.-B., Pettrã, J. Social ways: Learning multi-modal distributions of pedestrian trajectories with gans. In 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), 2964–2972, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPRW.2019.00359 (2019).

Brito, B., Zhu, H., Pan, W., Alonso-Mora, J. Social-vrnn: One-shot multi-modal trajectory prediction for interacting pedestrians. https://arxiv.org/2010.09056 (2020).

Salzmann, T., Ivanovic, B., Chakravarty, P., Pavone, M. & Trajectron++: Dynamically-feasible trajectory forecasting with heterogeneous data. In Computer Vision - ECCV, 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23–28,. Proceedings. Part XVIII683–7000. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58523-540 (Springer, 2020).

Mangalam, K., An, Y., Girase, H., Malik, J. From goals, waypoints & paths to long term human trajectory forecasting. In 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 15213–15222, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.01495 (2021).

Mnih, V. et al. Playing atari with deep reinforcement learning. Arxiv https://arxiv.org/1312.5602 (2013).

Martinez-Gil, F., Lozano, M. & Fernáindez, F. Strategies for simulating pedestrian navigation with multiple reinforcement learning agents. Auton. Agents Multi-Agent Syst. 29, 98–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10458-014-9252-6 (2015).

Torrey, L. Crowd simulation via multi-agent reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the Sixth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital Entertainment, AIIDE’10, 89-94 (AAAI Press, 2010).

Martinez-Gil, F., Lozano, M. & Fernández, F. Multi-agent reinforcement learning for simulating pedestrian navigation. In Adaptive and Learning Agents (eds Vrancx, P. et al.) 54–69 (Springer, 2012).

Casadiego, L. & Pelechano, N. From one to many: Simulating groups of agents with reinforcement learning controllers. In Intelligent Virtual Agents (eds Brinkman, W.-P. et al.) 119–123 (Springer, 2015).

Bastidas, L. C. Social Crowd Controllers Using Reinforcement Learning Methods (Springer, 2014).

Xu, D., Huang, X., Li, Z., Li, X. Local motion simulation using deep reinforcement learning. Trans. GIS24, 756–779, https://doi.org/10.1111/tgis.12620 (2020).

Colas, A. et al. Interaction fields: Intuitive sketch-based steering behaviors for crowd simulation. Comput. Graph. Forum 41, 521–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/cgf.14491 (2022).

Panayiotou, A., Kyriakou, T., Lemonari, M., Chrysanthou, Y. & Charalambous, P. Ccp: Configurable crowd profiles.In ACM SIGGRAPH 2022 Conference Proceedings, SIGGRAPH ’22. https://doi.org/10.1145/3528233.3530712 (Association forComputing Machinery, 2022).

Li, Y., Huang, T., Liu, Y., Chang, X. & Ding, G. Anchor-based crowd formation transformation. Comput. Anim. Virtual Worlds 33, e2111. https://doi.org/10.1002/cav.2111 (2022).

Li, Y., Huang, T., Liu, Y. & Ding, G. A spatio-temporal hierarchical model for crowd formation planning in large-scale performance. IEEE Access 8, 116685–116694. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2999059 (2020).

Zheng, X. et al. Visually smooth multi-uav formation transformation. Graph. Models 116, 101111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gmod.2021.101111 (2021).

Singh, S., Kapadia, M., Faloutsos, P. & Reinman, G. Steerbench: A benchmark suite for evaluating steering behaviors. Comput. Anim. Virtual Worlds 20, 533–548 (2009).

Kapadia, M., Wang, M., Singh, S., Reinman, G. & Faloutsos, P. Scenario space: characterizing coverage, quality, and failure of steering algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2011 ACM SIGGRAPH/Eurographics Symposium on Computer Animation, SCA ’11, 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1145/2019406.2019414 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2011).

Matsubara-Heo, S.-J., Mizera, S., Telen, S. Four lectures on euler integrals. SciPost Physics Lecture Notes (2023) https://doi.org/10.21468/scipostphyslectnotes.75 .

Bäuerle, N. & Rieder, U. Markov decision processes. Jahresber. Deutsch. Math.-Verein. 112, 217–243. https://doi.org/10.1365/s13291-010-0007-2 (2010).

Fujimoto, S., van Hoof, H. & Meger, D. Addressing function approximation error in actor-critic methods. Mach. Learn. https://arxiv.org/1802.09477 (2018).

Mnih, V. et al. Asynchronous methods for deep reinforcement learning. Mach. Learn. https://arxiv.org/1602.01783 (2016).

Jiang, H., Xie, J. & Yang, J. Action candidate based clipped double q-learning for discrete and continuous action tasks. AAAI Conf.. https://arxiv.org/2105.00704 (2021).

Manocha, D., Lin, M. C., Berg, J., Curtis, S. & Patil, S. Directing crowd simulations using navigation fields. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 17, 244–254. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVCG.2010.33 (2011).

Ramachandran, P., Zoph, B. & Le, Q. V. Searching for activation functions. Arxiv https://arxiv.org/1710.05941 (2017).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization, 1412.6980.

Pellegrini, S., Ess, A., Schindler, K., Gool, L. v. You’ll never walk alone: Modeling social behavior for multi-target tracking. In 2009 IEEE 12th International Conference on Computer Vision, 261–268, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV.2009.5459260 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, No. 62177005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. conceived the theoretical design, derived the formulas, implemented the experiments and wrote the manuscript. Y.C. contributed to the visualization aspect of the work. J.L. assisted Y.L. in conducting the experiments and writing the manuscript. T.H. provided financial support and project management. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Chen, Y., Liu, J. et al. Efficient crowd simulation in complex environment using deep reinforcement learning. Sci Rep 15, 5403 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88897-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88897-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Physical AI: bridging the sim-to-real divide toward embodied, ethical, and autonomous intelligence

Machine Learning for Computational Science and Engineering (2026)