Abstract

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) serve as a powerful framework for representation learning on graph-structured data, capturing the information of nodes by recursively aggregating and transforming the neighboring nodes’ representations. Topology in graph plays an important role in learning graph representations and impacts the performance of GNNs. However, current methods fail to adequately integrate topological information into graph representation learning. To better leverage topological information and enhance representation capabilities, we propose the Graph Topology Attention Networks (GTAT). Specifically, GTAT first extracts topology features from the graph’s structure and encodes them into topology representations. Then, the representations of node and topology are fed into cross attention GNN layers for interaction. This integration allows the model to dynamically adjust the influence of node features and topological information, thus improving the expressiveness of nodes. Experimental results on various graph benchmark datasets demonstrate GTAT outperforms recent state-of-the-art methods. Further analysis reveals GTAT’s capability to mitigate the over-smoothing issue, and its increased robustness against noisy data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Graph-structured data maps out intricate relations between various entities around the world, from the vast expanses of social networks1 to the dense construction of knowledge graphs2, and the intricate patterns of molecular structures3 even to 3D topologies of manifolds4. This data structure plays an essential part in complex relationship modeling. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and their variants are efficient tools for exploring graph-structured data, utilizing node features and graph structure to address challenges in network analysis. This capability makes GNNs widely applicable across various domains, including deciphering molecular structures5, navigating social networks6, formulating product suggestions7, or dissecting software programs8.

Convolution techniques in computer vision9,10 have been applied to graph-structured data, promoting advancements in GNNs. Based on different convolution definitions, GNNs are divided into two categories: spectral-domain11 and spatial-domain12,13,14. Spectral-domain GNNs define graph convolution through the lens of graph signal processing, based on the principle that convolving two signals in the space domain is equivalent to multiplying their Fourier transforms in the frequency domain. This concept originates from Bruna’s work11, with subsequent advancements and refinements made by notable works on ChebNet15, CayleyNet16, and GCN17. Spatial-domain GNNs perform convolution on the representations of each node and its neighbors directly to update states, and exhibit a wide variety of variants according to different neighboring information aggregation and integration strategies. Particularly, Graph Attention Network (GAT)18stands out owing to its attention-based neighborhood aggregation. This architecture enables nodes to weigh the significance of neighboring information during their feature update process. Building upon this, GAT219 introduces dynamic attention, demonstrating more robust and expressive capabilities.

While these methods make use of basic topological information, such as node degrees or edges, during message passing, they do not explicitly incorporate richer topological features. This limitation prevents GNNs from fully leveraging the inherent properties of the graph structure, which are crucial for understanding graph-structured data. For instance, in social networks20, the topological structure can reveal community patterns, influential entities, and the dynamics of information flow. In chemical informatics21, the molecular topology directly influences the chemical properties and reactivity of molecules. In biological networks22, analyzing topological differences helps understand cellular functions and disease mechanism. To address this limitation, some GNNs23,24,25 leverage the topological infomation, by adjusting factors like message passing weights or choosing specific nodes for information propagation. You’s and Tian’s work26,27 attempts to enhance node expressiveness by concatenating the extracted topological information with node representation. However, node representations and topology representations are essentially two different modalities. Wang’s and Baltrušaitis’s work28,29 indicates that simply concatenating data from different modalities, while ignoring the interactions between these modalities, may hinder the network from effectively learning useful information from each modality.

Motivated by the above issues, we propose Graph Topology Attention Networks (GTAT) to address the inadequate utilization of topological information and the limitation of unimodal configuration. In specific, GTAT starts by extracting topology features from the graph’s structure, and then encodes them into topology representations. We take the infuluence of the node local topology into account by encoding the topology information as another input into the model. Then, we compute two types of attention scores and use cross attention mechanism to process both the node representations and the extracted topology features. This integration enables topology features to be incorporated into node representations and ensures the relationships in graph effectively captured, achieving a more robust and expressive graph model.

The contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

-

We propose a novel graph neural network framework, GTAT, which enhances the utilization of topological information for processing graph-structured data. In this framework, we treat node feature representations and extracted topology representations as two separate modalities, which are then inputted into the GNN layers.

-

We explore the feasibility of applying the cross attention mechanism in GNNs. Our approach calculates attention scores for both node feature representations and node topology representations, then employ a cross attention mechanism to integrate these two sets of representations. This integration allows the model to dynamically adjust the influence of node features and topological information, enhancing the representation capability.

-

Experimental results on nine diverse datasets demonstrate our model has a better performance than state-of-the-art models on classification tasks. Further analysis involving variations in model depth and noise levels reveals GTAT’s capability to mitigate the over-smoothing issue, and its increased robustness against noisy data. These results highlight that GTAT can be used as a general architecture and applied to different scenarios.

Related work

Graph neural networks

Different GNNs employ various aggregation schemes for a node to aggregate messages from its neighbors. GCN17 utilizes a layer-wise propagation technique, employing a localized first-order approximation of spectral graph convolutions to encode representations. SAGE30 learns a function to generate embeddings from a node’s local neighborhood, enabling predictions on previously unseen data. SGC31 simplifies the training process by reducing the number of non-linear layers and merges multiple layers of graph convolution into a single linear transformation. FAGCN32 optimizes neighborhood information aggregation by analyzing the spectral properties of graphs, employing different strategies for handling high-frequency and low-frequency signals. Attention mechanism33 empowers GATs to selectively focus on significant neighborhood information while updating node representations, thus pioneering a new approach in graph representation learning. GAT18 employs a self-attention mechanism, which calculates attention coefficients for each neighbor of a node and utilizes them to weight corresponding neighbor features during aggregation, permitting the GAT to assign more considerable weights to more relevant neighbors. GAT219 employs a dynamic attention mechanism to enhance the model’s expressive abilities, accommodating scenarios where different keys possess varying degrees of relevance to different queries.

GNNs with topology

Leveraging graph topology has become more and more popular in graph representation learning. mGCMN34 incorporates motif-induced adjacency matrices into its message passing framework, adjusting weights to capture complex neighborhood structures. TAGCN35 slides a set of fixed-size learnable filters over the graph, where each filter adapts to the local topology. P-GNNs26 samples multiple sets of anchor nodes and applies a distance-weighted aggregation scheme to differentiate nodes’ positions information. SubGNN36 learns disentangled representations of subgraphs by using routing mechanism to handle subgraph internal topology, position, and connectivity, enhancing performance on subgraph prediction tasks. To learn deep embeddings on the high-order graph-structured data, Hyper-Conv37. extends traditional graphs, permitting edges to connect to any number of vertices, thus altering the aggregation methods among nodes. Given the importance of topological information, we extract and encode it to enhance model’s representation ability.

Cross attention mechanism

The concept of the cross attention mechanism was first proposed in the Transformer model38. Cross attention mechanism bridges two distinct sequences from diverse modalities such as text, sound, or images. Cross attention provides a flexible framework that allows for interactions between different modalities39,40, enhancing mutual understanding. Exploiting this concept, the Perceiver model41 processes input byte arrays by alternating between cross attention and latent self-attention blocks. Meta’s Segment Anything Model42 leverages cross attention to connect the prompts and image information, fostering enhanced interactions and richer embeddings. MMCA43 uses cross attention module to generate cross attention maps for each pair of class feature and query sample feature, making the extracted feature more discriminative. Recently, some works44,45 have also adopted cross-attention mechanisms in graph-related tasks. However, most of these studies focus on using cross-attention to facilitate interactions between graph modules and non-graph modules. In this study, we employ the cross-attention mechanism to enable modality interaction within the graph module itself, without requiring the assistance of non-GNN modules. This distinction allows for more efficient and intrinsic interactions within the graph structure itself.

Method

Framework

As illustrated in Figure 1, our framework begins with the topology feature extraction (TFE) for each node. After getting the set of topology representations, we apply Graph Cross Attention (GCA) layers to update node feature representations and topology representations. Lastly, the model utilizes the node feature representations from the final layer to predict node classifications. Our methodology presents an innovative fusion of original feature representations and the topology representations, utilizing a unique cross attention mechanism on graph to enhance the expressive capabilities of each node. The following sections comprehensively elaborate on our approach.

GTAT framework. Given a graph \(\mathcal {G}\) with \(N\) nodes, along with a set of node feature representations H, we first obtain the GDV of these nodes through the TFE. Subsequently, we use MLP transforms GDV into a set of topology representations T. GTAT layer receives \(\mathcal {G}\) and these two representations as input, then transforms and outputs two updated sets of representations. Finally, based on the set of node feature representations, our model outputs the predictions of nodes’ classifications.

Topology feature extraction

To extract the information inherent in graph, we obtain the topology representations based on the graphlet degree vector (GDV)22,46 for each node. GDV is a count vector that represents the distribution of nodes in specific orbits of graphlets. Graphlets, defined as small connected non-isomorphic induced subgraphs within a graph, succinctly capture the neighboring structure of each node in the network. And an orbit can be thought of as a unique position or role a node can have within a graphlet. For instance, each node in a triangle (a three node graphlet) has the same role, so they belong to the same orbit. GDV is a vector to count the participation times of different orbits across the local distinct graphlets. The GDV delivers a measure of the node’s local network topology feature, enhancing model’s understanding of the graph structure.

Figure 2 shows all four different orbits with up to three nodes and the GDV calculating of node \(\nu\). In fact, there are 15 distinct orbit types for graphlets with up to four nodes, and 73 types for graphlets with up to five nodes. We utilize the Orbit Counting Algorithm (OCRA)47 to compute the GDV of nodes within a network. OCRA offers a combinatorial method for the enumeration of graphlets and orbit signatures of network nodes, reducing the computational complexity encountered in the counting of graphlets. The time complexities for computing the GDVs of these two dimensions are respectively \(O\left( n \cdot d^3\right)\) and \(O\left( n \cdot d^4\right)\), where n is the number of nodes and d is the maximum degree of the nodes.

Up: Four orbits with different color. Down: The computation of GDV for node \(\nu\) in graph \(\mathcal {G}\). This diagram illustrates all instances where node \(\nu\) appears in four distinct orbits. Correspondingly, the GDV for \(\nu\) is [2, 1, 0, 1], reflecting the appearance count of \(\nu\) in these orbits.

Building on the aforementioned approach, this study employs the GDV as the extracted node topology feature. The dimensionality of each node’s GDV corresponds to the number of orbits, representing its topological characteristics. These GDVs, after being normalized and processed through a multilayer perceptron (MLP)48, serve as the topology representations inputted into the network. To balance the computational efficiency and prediction accuracy, we employ the 73-dimensional GDV. The comparative experiments are showed in Section 4.

Graph cross attention layer

After obtaining the topology representation, our approach introduces the computation of two types of attention: the feature attention and a novel topology attention, thereby implementing a cross attention mechanism on graph. The structure of GCA layer is depicted in Figure 3.

Our GCA layer receives a set of node feature representations, \({H}_l=\left\{ {h}_1, {h}_2, \ldots , {h}_N\right\}\), and a set of topology representations, \({T}_l=\left\{ {t}_1, {t}_2, \ldots , {t}_N\right\}\), where N is the number of nodes at layer l. Following the methodology in GAT, we calculate the feature attention score between feature representations of nodes and their corresponding neighbors:

where \({h}_i\) and \({h}_j\) are the feature representations of nodes \(i\) and \(j\), while W and a represent a weight matrix and a shared parameter vector, respectively. This calculation embodies the inherent attributes of the nodes and assigns more considerable weights to more relevant neighbors.

The structure of GCA layer. Inputs is a set of node feature representations, \({H}_l \in \mathbb {R}^{N\times F_1}\) and a set of node topology representations, \({T}_l \in \mathbb {R}^{N\times F_2}\), where N is the number of nodes at layer l. After computing two attention matrices, denoted as \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\), we employ message passing(M.P.) mechanism to get the new representations \({H}_{l+1} \in \mathbb {R}^{N\times F_3}\) and \({T}_{l+1} \in \mathbb {R}^{N\times F_2}\).

Furthermore, we introduce a new form of attention score, topology attention score. This score is calculated between topology representations of nodes and their corresponding neighbors:

where \({t}_i\) and \({t}_j\) are the topology representations of node \(i\) and node \(j\), with \({a}_t\) being a shared parameter vector. Then the feature attention scores and topology attention scores are normalized as :

and

where \(\alpha _{i j}\) is the feature attention coefficient between node \(i\) and node \(j\), and \(\beta _{i j}\) serves as the topology attention coefficient, enabling the model to capture the local substructure of each node in the network. Additionally, \(\mathcal {N}_{i}\) represents the set of neighbors of node i, and it can be defined as follows:

where \(\mathcal {V}\) represents the set of nodes in the graph, and \(\mathcal {E}\) represents the set of edges.

Following the two attention computations, we implement the cross attention mechanism, which intertwines the node feature representations and the topology representations. The node feature representation is updated with the computed topology attention coefficients as:

where \(\sigma\) is a nonlinearity and \({W} \in \mathbb {R}^{F_3\times F_1}\) represent a weight matrix. Simultaneously, the topology representation is updated with the calculated feature attention coefficients :

Finally, the layer outputs a new set of node feature representations, \({H}_{l+1}=\left\{ {h}_1^{\prime }, {h}_2^{\prime }, \ldots , {h}_N^{\prime }\right\}\), and a set of topology representations, \({T}_{l+1}=\left\{ {t}_1^{\prime }, {t}_2^{\prime }, \ldots , {t}_N^{\prime }\right\}\).

It’s worth mentioning that dynamic attention mechanism, which is introduced in GAT2, also performs well across various tasks. The dynamic attention in GAT2 diverges from GAT’s static counterpart by adjusting its weights based on the query, thus accommodating scenarios where different keys possess varying degrees of relevance to different queries. The dynamic attention calculation in GAT2 is formulated as follows:

To equip our model with dynamic attention, we further propose another version: GTAT2. In GTAT2, we employ the dynamic attention mechanism as utilized in GAT2 for the computation of two attention scores, as Equation 8 and Equation 9:

Both the node feature and topology representations in GTAT2 are updated similarly to those in GTAT. Experiments and analysis on GTAT and GTAT2 are conducted subsequently.

The cross action of the node and topology representations allows for the capture of both node intrinsic attributes and topological relations, thereby significantly augmenting the prediction accuracy of our model.

Experiments

Datasets

In our experiments, we use nine commonly used benchmark datasets, namely three citation networks datasets (i.e., Cora, Citeseer, and PubMed)49, two Amazon sale datasets (i.e., Computers and Photo)50, two coauthorship datasets (i.e., Physics and CS), one Wikipedia-based dataset (i.e., WikiCS)51, and one arxiv papers dataset (i.e., Arxiv)52. Statistics for all datasets can be found in Table 1. The resources we used are all from the PyTorch Geometric Library53.

Experimental setup

All experiments are implemented in PyTorch and conducted on a server with two NVIDIA GeForce 4090 (24 GB memory each). We conduct 20 runs, reporting the mean values alongside the standard deviation. The search space for hyper-parameters encompasses: hidden size options of \({\left\{ 8, 16, 32, 64 \right\} }\), learning rate choices of \({\left\{ 0.01, 0.005 \right\} }\), dropout values of \({\left\{ 0.4, 0.6 \right\} }\), weight decay options of \({\left\{ 1E-3, 5E-4 \right\} }\), and selection of attention heads from \({\left\{ 1, 2, 4, 8 \right\} }\)for models using attention mechanism. We hold the number of layers constant at 2. All methods utilize an early stopping strategy54 based on validation loss, with patience of 100, and all are trained using a full-batch approach. In all cases, we randomly select 20 and 30 nodes per class for the training and validation, respectively, and the remaining nodes are used for testing. We use NLL Loss as the loss function for the model:

where C is the number of classes in the classification task, \(\hat{y}_{i, c}\) is the predicted probability of sample \(i\) being classified into class \(c\), and \(y_{i, c}\)is the ground truth label. We utilize the Adam optimizer55 to minimize the loss function and optimize the parameters of these models.

Node classification results

The comparative methods in our study involve nine different algorithms: GCN17, GraphSAGE (SAGE)30, SGC31, FAGCN32, GAT18, GAT219, Hyper-Conv37, mGCMN34 and Dir-GNN56.

Table 2 shows the average accuracy and standard deviation of different models. Except for two datasets, GTAT or GTAT2 achieves the best results in all other datasets. Compared to GATs, GTATs show better performance across all datasets due to the extracted topology features and the cross attention mechanism. Specifically, GTAT achieves an average accuracy improvement of 0.53% across nine datasets compared to GAT, and GTAT2 outperforms GAT2 with an accuracy improvement of 0.48%. Compared to Hyper-Conv. and mGCMN, which utilize topological information, our model also demonstrates better accuracy. While Hyper-Conv. and mGCMN merely adjust the message-passing pathways or weights based on the extracted topological structure, our method receives the extracted topology features as an additional modality. This mechanism enables GTATs to fit the impact of the topological structure on node representation, contributing to more accurate and reliable predictions. Compared to the earlier proposed SGC, GCN, and SAGE models, the GTATs exhibit superior performance.

FAGCN’s effectiveness in the Physics and Cs datasets, where the node features have high dimensions, can be attributed to its adaptive integration of low-frequency and high-frequency signals from the raw features. However, GTATs outperform FAGCN across all other seven datasets. Particularly for the Arxiv dataset, which has low node feature dimensions, GTAT outperforms FAGCN by 4.25%, highlighting GTATs’ capability to achieve higher accuracy with limited node features.

In summary, our GTAT models demonstrate outstanding performance across all nine datasets spanning four distinct data types, showcasing their broad applicability in handling diverse graph-structured data.

Effectiveness of cross attention

To further explore the impact of the cross attention mechanism embedded in our model, we conduct series of experiments based on GATs with two different configurations. (1) GATs+A, which updates both the node feature representations H and the topology representations T using the topology attention coefficients \(\beta\). (2) GATs+B updates only the node feature representations H based on the topology attention coefficients \(\beta\), while the topology representations T remain constant. As shown in Table 3, our method presents the best performance across the most of datasets except the Computers. These results support the importance of utilizing the potential of both node feature and topology representations through our cross attention mechanism to attain optimal performance.

Over-smoothing analysis

A critical challenge in GNNs is the over-smoothing issue57, which limits the number of layers that can be effectively stacked. As the number of layers increases, the nodes become less and less distinguishable, making the performance of the model drop sharply.

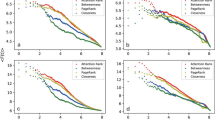

To verify whether topology representations and cross attention could alleviate the over-smoothing issue, we select four different types of datasets and compare the performance of GTATs and GATs at varying depths. There are few significant differences between the models in initial layers, as shown in Figure 4. However, as the depth increases, the GTATs demonstrate more stable performance, avoiding the drastic decline observed in GATs.

Figure 5displays the t-SNE58 plots of the node representations with 20 layers of GAT and GTAT on the Physics dataset. The t-SNE plot provides a visual description of high-dimensional data by projecting them into 2D space, aiding in the identification of relevant patterns. From this visualization, it is evident that GTAT achieve clearer node clustering than GAT. Besides, Figure 6 shows the node classification accuracy curves and loss curves of GATs and our proposed GTATs. It can be seen that GTATs can converge more quickly and stably while achieving better accuracy.

Over-smoothing occurs when node representations become increasingly similar, rendering the model incapable of effectively distinguishing between different nodes. To quantify the similarity between node representations, we selected Dirichlet energy (\(E_D\))59 as our metric:

where \(n_e\) denotes the total number of edges, \({h}_i\) represents the representation of node i, and \(A_{ij}\) is the corresponding element in the adjacency matrix. A higher \(E_D\) indicates greater dissimilarity between node representations. Figure 7 shows that the Dirichlet energy at each layer of the GTATs is exponentially higher than that of the GATs, indicating that GTATs better preserve the distinctiveness of node embeddings even as the depth increases.

GTATs’ better performance at deep layers can be attributed to the topology attention in our model architecture, which establishes the relationships between nodes from the perspective of the topology they inhabit. Topology attention enhances the distinctiveness of node feature representations, thereby improving the expressiveness of the model.

Robustness analysis

Better robustness indicate stronger stability of the model when facing noisy data. To evaluate the robustness of the GTATs, we conduct experiments on four different types of datasets and compare the performance of GTATs and GATs under random feature attack (RFA). RFA19 intentionally corrupts node features in the graph to evaluate each model’s ability when facing the perturbations caused by feature attacks. In particular, the attack is implemented by randomly modifying the nodes features according to a noise ratio \(0 \le p \le 1\). For node \(i\), its representations is modified as follows:

where noise is a vector sampled from a Gaussian distribution, \(\mathcal {N}\), with mean zero and variance one.

Figure 8 shows the node classification accuracy on four datasets as a function of the noise ratio p. As p increases, the accuracy of all models decrease asour expection. However, GTATs show a milder degradation in accuracy compared to GATs, which show a steeper descent. The experimental results show that GATs, relying solely on node representations, face difficulty adapting to increased noise levels and suffer more obvious performance declines. GTATs’ resilience to noise can be attributed to the extracted topology presentations and the cross attention mechanism. Both allow GTATs to maintain better differentiation and stability of node features under RFA. These results clearly demonstrate the robustness of GTATs over GATs in noisy settings.

Efficiency analysis

Similar to other deep learning models, GTAT may need to be deployed on small devices. To compare the scale of the GNN models, we carry out an analysis of the model parameter counts and their performance across three datasets of varying sizes. For a fair comparison, all models in this study adhere to the same hyperparameters: 2 attention heads, an hidden layer of 64 dimensions, a dropout rate of 0.6, a learning rate of 0.01, and a weight decay set to 0.001. As shown in Table 4, it’s clear that GTATs have only a slight increase in parameter counts compared to GATs, yet its performance is notably better. In contrast to GATs, GTATs additionally employ a MLP to convert the GDV into topology representation and \({a}_t\) to calculate topology attention.

Actually, the more orbits there are, the more local topological information a node can obtain. GTATs may benefit from sufficient topology information, but face a heavier computational burden. To understand the influence of orbits with different quantities on model predictions, we conduct experiments across three distinct dataset scales and statistically analyze the time required by the OCRA to compute GDVs of them. In this study, GTATs_4 represent the models that utilize orbits with up to four nodes, and GTATs_5 denote the versions that utilize orbits with up to five nodes. The results in Table 5 show that orbits with up to five nodes, while taking more time to compute than those with four nodes, enhance the accuracy of the predictions. Due to the lack of more efficient algorithm, employing orbits with up to six nodes, while potentially increasing accuracy, would significantly increase the computational time, especially for larger and dense networks. In order to balance computational efficiency with accuracy gains, this paper counts the 73 different orbits with up to five nodes as the nodes’ topology features.

Conclusion

In this paper, we introduce the GTAT, an innovative framework designed to harness the topological potential of graph-structured data. GTAT distinctively merges node and topology features through a cross attention mechanism, enhancing node representations and capturing graph structure information. Experimental results indicate our approach has a better performance than state-of-the-art existing models on classification tasks. Besides, the performance of GTAT with variations in depth and noise suggests that its topology representation combined with cross attention mechanism not only alleviate over-smoothing issue but also enhances the model’s robustness. Future works will focus on refining the GTAT and exploring its potential applications in diverse contexts.

Data availability

Codes are available at https://github.com/kouzheng/GTAT.

References

Majeed, A. & Rauf, I. Graph theory: A comprehensive survey about graph theory applications in computer science and social networks. Inventions 5, 10 (2020).

Ji, S., Pan, S., Cambria, E., Marttinen, P. & Philip, S. Y. A survey on knowledge graphs: Representation, acquisition, and applications. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems 33, 494–514 (2021).

Qian, Y. et al. Molscribe: robust molecular structure recognition with image-to-graph generation. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 63, 1925–1934 (2023).

Chen, S. et al. Deep unsupervised learning of 3d point clouds via graph topology inference and filtering. IEEE transactions on image processing 29, 3183–3198 (2019).

Duvenaud, D. K. et al. Convolutional networks on graphs for learning molecular fingerprints. Advances in neural information processing systems 28 (2015).

Fan, W. et al. Graph neural networks for social recommendation. In The world wide web conference, 417–426 (2019).

Ying, R. et al. Graph convolutional neural networks for web-scale recommender systems. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery & data mining, 974–983 (2018).

Allamanis, M., Brockschmidt, M. & Khademi, M. Learning to represent programs with graphs. arXiv preprint[SPACE]arXiv:1711.00740 (2017).

LeCun, Y., Bottou, L., Bengio, Y. & Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE 86, 2278–2324 (1998).

Su, Y. et al. Nano scale instance-based learning using non-specific hybridization of dna sequences. Communications Engineering 2, 87 (2023).

Bruna, J., Zaremba, W., Szlam, A. & LeCun, Y. Spectral networks and locally connected networks on graphs. arXiv preprint[SPACE]arXiv:1312.6203 (2013).

Xu, K., Hu, W., Leskovec, J. & Jegelka, S. How powerful are graph neural networks? In International Conference on Learning Representations (2019).

Monti, F. et al. Geometric deep learning on graphs and manifolds using mixture model cnns. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 5115–5124 (2017).

Ghorvei, M., Kavianpour, M., Beheshti, M. T. & Ramezani, A. Spatial graph convolutional neural network via structured subdomain adaptation and domain adversarial learning for bearing fault diagnosis. Neurocomputing 517, 44–61 (2023).

Defferrard, M., Bresson, X. & Vandergheynst, P. Convolutional neural networks on graphs with fast localized spectral filtering. Advances in neural information processing systems 29 (2016).

Levie, R., Monti, F., Bresson, X. & Bronstein, M. M. Cayleynets: Graph convolutional neural networks with complex rational spectral filters. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 67, 97–109 (2018).

Kipf, T. N. & Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) (2017).

Veličković, P. et al. Graph Attention Networks. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) (2018). Accepted as poster.

Brody, S., Alon, U. & Yahav, E. How attentive are graph attention networks? In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) (2022).

Momennejad, I. Collective minds: social network topology shapes collective cognition. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 377, 20200315 (2022).

Smith, A. D., Dłotko, P. & Zavala, V. M. Topological data analysis: concepts, computation, and applications in chemical engineering. Computers & Chemical Engineering 146, 107202 (2021).

Pržulj, N. Biological network comparison using graphlet degree distribution. Bioinformatics 23, e177–e183 (2007).

Feng, Y., You, H., Zhang, Z., Ji, R. & Gao, Y. Hypergraph neural networks. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence 33, 3558–3565 (2019).

Sankar, A., Zhang, X. & Chang, K. C.-C. Motif-based convolutional neural network on graphs. arXiv preprint[SPACE]arXiv:1711.05697 (2017).

Zhao, Q., Ye, Z., Chen, C. & Wang, Y. Persistence enhanced graph neural network. In International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, 2896–2906 (PMLR, 2020).

You, J., Ying, R. & Leskovec, J. Position-aware graph neural networks. In International conference on machine learning, 7134–7143 (PMLR, 2019).

Tian, Y., Zhang, C., Guo, Z., Zhang, X. & Chawla, N. Learning mlps on graphs: A unified view of effectiveness, robustness, and efficiency. In The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations (2022).

Wang, X., Wang, X., Jiang, B., Tang, J. & Luo, B. Mutualformer: Multi-modal representation learning via cross-diffusion attention. International Journal of Computer Vision 1–22 (2024).

Baltrušaitis, T., Ahuja, C. & Morency, L.-P. Multimodal machine learning: A survey and taxonomy. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 41, 423–443 (2018).

Hamilton, W., Ying, Z. & Leskovec, J. Inductive representation learning on large graphs. Advances in neural information processing systems 30 (2017).

Wu, F. et al. Simplifying graph convolutional networks. In International conference on machine learning, 6861–6871 (PMLR, 2019).

Bo, D., Wang, X., Shi, C. & Shen, H. Beyond low-frequency information in graph convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 35, 3950–3957 (2021).

Lin, W. et al. Limit and screen sequences with high degree of secondary structures in dna storage by deep learning method. Computers in Biology and Medicine 166, 107548 (2023).

Li, X., Wei, W., Feng, X., Liu, X. & Zheng, Z. Representation learning of graphs using graph convolutional multilayer networks based on motifs. Neurocomputing 464, 218–226 (2021).

Du, J., Zhang, S., Wu, G., Moura, J. M. & Kar, S. Topology adaptive graph convolutional networks. arXiv preprint[SPACE]arXiv:1710.10370 (2017).

Alsentzer, E., Finlayson, S., Li, M. & Zitnik, M. Subgraph neural networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33, 8017–8029 (2020).

Bai, S., Zhang, F. & Torr, P. H. Hypergraph convolution and hypergraph attention. Pattern Recognition 110, 107637 (2021).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 30 (2017).

Huang, Z. et al. Ccnet: Criss-cross attention for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 603–612 (2019).

Chen, Z. et al. Alien: Attention-guided cross-resolution collaborative network for 3d gastric cancer segmentation in ct images. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 96, 106500 (2024).

Jaegle, A. et al. Perceiver: General perception with iterative attention. In International conference on machine learning, 4651–4664 (PMLR, 2021).

Kirillov, A. et al. Segment anything. arXiv preprint[SPACE]arXiv:2304.02643 (2023).

Wei, X., Zhang, T., Li, Y., Zhang, Y. & Wu, F. Multi-modality cross attention network for image and sentence matching. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 10941–10950 (2020).

Huang, W., Wu, J., Song, W. & Wang, Z. Cross attention fusion for knowledge graph optimized recommendation. Applied Intelligence 1–10 (2022).

Cai, W. & Wei, Z. Remote sensing image classification based on a cross-attention mechanism and graph convolution. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 19, 1–5 (2020).

Milenković, T., Ng, W. L., Hayes, W. & Pržulj, N. Optimal network alignment with graphlet degree vectors. Cancer informatics 9, CIN–S4744 (2010).

Hočevar, T. & Demšar, J. A combinatorial approach to graphlet counting. Bioinformatics 30, 559–565 (2014).

Rumelhart, D. E., Hinton, G. E. & Williams, R. J. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. nature 323, 533–536 (1986).

Yang, Z., Cohen, W. & Salakhudinov, R. Revisiting semi-supervised learning with graph embeddings. In International conference on machine learning, 40–48 (PMLR, 2016).

Shchur, O., Mumme, M., Bojchevski, A. & Günnemann, S. Pitfalls of graph neural network evaluation. Relational Representation Learning Workshop, NeurIPS 2018 (2018).

Mernyei, P. & Cangea, C. Wiki-cs: A wikipedia-based benchmark for graph neural networks. arXiv preprint[SPACE]arXiv:2007.02901 (2020).

Hu, W. et al. Open graph benchmark: Datasets for machine learning on graphs. Advances in neural information processing systems 33, 22118–22133 (2020).

Fey, M. & Lenssen, J. E. Fast graph representation learning with PyTorch Geometric. In ICLR Workshop on Representation Learning on Graphs and Manifolds (2019).

Prechelt, L. Early stopping-but when? In Neural Networks: Tricks of the trade, 55–69 (Springer, 2002).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint[SPACE]arXiv:1412.6980 (2014).

Rossi, E. et al. Edge directionality improves learning on heterophilic graphs. In Learning on Graphs Conference, 25–1 (PMLR, 2024).

Rusch, T. K., Bronstein, M. M. & Mishra, S. A survey on oversmoothing in graph neural networks. arXiv preprint[SPACE]arXiv:2303.10993 (2023).

Van der Maaten, L. & Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-sne. Journal of machine learning research 9 (2008).

Cai, C. & Wang, Y. A note on over-smoothing for graph neural networks. arXiv preprint[SPACE]arXiv:2006.13318 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62172114, 62473104), the Fundings by Science and Technology Projects in Guangzhou (2023A03J0113). Our heartfelt thanks go out to Yanqing Su, Zhihong Chen and Minjia Huangfu for their unique companionship and invaluable discussions during this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J: Conceptualization, Methodology, Programing, Visualization and Original Draft Preparation. Q: Visualization, Investigation, Writing-Review and Editing. Y: Visualization and Formal Analysis. B: Investigation and Validation. X: Resources, Supervision. Z (Corresponding Author): Project Administration, Conceptualization, Writing-Review and Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This study did not involve human or animal subjects, and thus, no ethical approval was required.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, J., Ain, Q.T., Liu, Y. et al. GTAT: empowering graph neural networks with cross attention. Sci Rep 15, 4760 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88993-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88993-3