Abstract

This paper proposes a novel fixed-time prescribed performance sliding mode control method, specifically designed to address trajectory tracking issues in wheeled mobile robots (WMRs) affected by wheel slipping, skidding (WSS), and external disturbances. A new prescribed performance sliding surface is first introduced based on a prescribed performance function (PPF) and a non-singular fast terminal sliding function (NFTSF). This design ensures that tracking errors converge to zero within a fixed time while maintaining stability by keeping error states within predefined limits. A novel fixed-time prescribed performance non-singular fast terminal sliding mode control (FPP-NFTSMC) algorithm is proposed based on the sliding function. The control method integrates a uniform second-order sliding mode (USOSM) algorithm to provide a continuous control signal, effectively reducing the chattering effect. This method combines the benefits of PPF, NFTSMC, and USOSM algorithm to achieve high-precision position tracking, minimize chattering, guarantee fixed-time convergence, ensure tracking errors remain within bounds, and maintain robustness against WSS, and external disturbances. The fixed-time stability of the WMR systems is demonstrated by the Lyapunov stability theory. The effectiveness of the proposed method is validated through simulations of tracking straight-line and U-shaped trajectories.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, wheeled mobile robots (WMRs) have increasingly been utilized in various fields, including industrial automation, logistics, healthcare, household tasks, and hazardous environments with limited human access1,2,3,4,5,6. These versatile robots offer unparalleled flexibility and efficiency, capable of performing tasks either autonomously or with human oversight. Effective control is vital for their efficient operation and safety, allowing them to navigate, interact with their surroundings, and complete tasks accurately and efficiently. However, achieving precise and robust control is challenging due to the complex dynamics of WMRs and environmental uncertainties. Robustness is crucial for managing diverse operating conditions like WSS. These factors are key considerations in designing and controlling of WMRs, requiring robust control strategies to minimize their impact and enhance overall performance and safety.

In literature, many dynamics model-based control methods have been investigated to enhance robot tracking performance like computed torque control7,8, adaptive control9,10, fuzzy logic control11, neural network-based control12,13, and sliding mode control (SMC)14,15,16. Compared to other methods, SMC is often considered an effective control approach, particularly valued for its robustness in handling uncertainties, and external disturbances in nonlinear dynamic systems. SMC has been successfully applied to WMRs, ensuring system stability by driving it toward a desired trajectory or state17. Especially, it offers excellent tracking performance and stability with a relatively simple design process. Despite these advantages, SMC is not without its drawbacks. One of the primary limitations is that it only guarantees asymptotic stability due to utilizing the linear sliding function, meaning that the system’s state variables will eventually converge to the desired equilibrium point, it may take an indefinite amount of time to do so. This gradual convergence can be a significant limitation in applications where rapid stabilization is critical. Additionally, SMC is known for causing the chattering phenomenon, which involves rapid oscillations around the sliding surface due to high-frequency switching control actions.

Finite-time control is widely recognized as an effective control strategy, especially appreciated for its ability to stabilize the systems. Unlike traditional control methods, which typically guarantee asymptotic stability, where the system state approaches to desired equilibrium point as time goes to infinity, finite-time control ensures that the convergence occurs within a finite period of time. This characteristic is crucial for applications that require rapid stabilization and precise timing, such as robotics18,19, aerospace systems20,21, and electrical circuits22. In the SMC family, finite-time convergence and stability can be obtained by using non-linear sliding functions instead of linear one; for example, terminal sliding mode control (TSMC)23, fast TSMC24,25, non-singular TSMC26,27, and non-singular fast TSMC (NFTSMC)28,29,30. Besides its advantages, the convergence speed of finite-time control approaches can be notably influenced by the system’s initial conditions. In many practical scenarios, when the initial conditions deviate significantly from the nominal values for which the controller was designed, the system may experience slower convergence rates or fail to achieve the desired state within the specified finite time. To overtake the problem, fixed-time stability has been developed, which guarantees that system states reach a desired equilibrium within a predetermined, fixed amount of time regardless of the initial state31. By providing reliable and predictable convergence times, fixed-time stability continues to play a vital role in increasing the safety, performance, and reliability of modern control systems, such as spacecraft32, underwater vehicle33, robot manipulators34,35, and mobile robots36.

In order to minimize the chattering phenomenon, a common approach is to replace the discontinuous signum function in switching control law by a continuous one. In this approach, the most popular method is the boundary layer technique37,38. While this approach decreases the chattering of the control input, it results in the system state not being exactly on the sliding surface but rather within a region around it, which reduces the tracking accuracy of the controlled systems. Another approach involves using high-order sliding mode (HOSM) that transfers the discontinuity to a higher-order derivative, effectively reducing chattering39,40. The super-twisting algorithm (STA) is a second-order sliding mode control method widely used in control systems to ensure robust and precise performance despite uncertainties and disturbances41,42. Moreover, it can bring the system state to the sliding surface in finite time, ensuring rapid response and stability. Unfortunately, the convergence time of STA still depends on system’s initial conditions.

To ensure robot stability, the essential is to maintain state errors within a defined boundary. The prescribed-performance control (PPC) strategy is an advanced control method that focuses on setting measurable outputs for a system and designing a control method to meet specific operational goals. This includes ensuring fast transient response, accurate steady-state performance, robustness against disturbances, and limiting overshoot43,44,45. PPC is especially useful for managing complex and uncertain systems, in which conventional control methods may fall short. In this approach, a prescribed performance function (PPF) and an error transformation function (ETF) are applied to achieve specific control objectives. The PPF plays a vital role in maintaining tracking errors within specified bounds over time, which can be critical in safety-critical applications. The ETF is a technique used in control systems to modify the error signal before it is processed by the control algorithm. The transformed error can improve the overall control performance, leading to faster convergence, increased robustness, and better stability of the controlled system. By explicitly defining desired performance criteria, PPC can enhance a system’s robustness against dynamic uncertainties and external disturbances, leading to superior performance46,47,48.

In light of the aforementioned motivations, a novel fixed-time prescribed-performance NFTSMC (FPP-NFTSMC) algorithm, specifically designed for WMRs, is presented in this article. The proposed controller aims to achieve control objectives despite the presence of WSS and external disturbances, including high tracking accuracy, fast convergence, reduced chattering, singularity elimination, fixed-time convergence, and a bounded range of tracking errors. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first application of fixed-time prescribed performance SMC for mobile robots. To demonstrate the efficiency of the designed controller, two simulation examples are conducted: tracking a simple straight trajectory and navigating a U-shaped trajectory. The following briefly describes the primary contributions of this paper:

-

Introduce a novel prescribed-performance NFTSF by integrating transformed errors, which effectively addresses the singularity problem,

-

Propose a novel FPP-NFTSMC approach using the proposed sliding surface and USOSM algorithm to improve WMRs tracking accuracy under total impacts of WSS, and external disturbances,

-

Attain high control performance with low tracking errors, rapid convergence, no singularity problem, and constrained tracking errors within a prescribed boundary,

-

Mitigate chattering effect in control input by applying the USOSM method,

-

Achieve stability and ensure fixed-time convergence of the WMR system using Lyapunov stability theory.

The organization of this study is presented as following:

-

Section II presents the kinematic and dynamic models of a four-WMR and covers some foundational concepts necessary for understanding the control methodologies.

-

Section III presents the design of the proposed prescribed-performance sliding surface and the proposed FPP-NFTSMC. This section includes a detailed stability analysis and fixed-time convergence of the four-WMR.

-

Section IV showcases the simulation results conducted to evaluate the designed control algorithm in two different working examples.

-

Section V concludes the paper, summarizing the findings and contributions.

Problem formulation

Preliminaries

Throughout the paper, the notation \(\lfloor {x}\rceil ^\alpha = \left| x\right| ^\alpha \textrm{sign}(x)\) is used, where \(x\in {\mathbb {R}}\), \(\forall \alpha \ge 0\), and \(\textrm{sign}(\cdot )\) represents signum function. When \(\alpha = 0\), \(\lfloor {x}\rceil ^0= \textrm{sign}(x)\).

Lemma 1

49:

Consider the system

with

where \(\gamma> 0\), \(|\dot{d}| \le d_{max}\), and \(d_{max}> 0\).

If \(K_1, K_2\) are selected to satisfy the conditions

\(K = \left\{ (K_1, K_2) \in {\mathbb {R}}^2 \mid 0<K_1 \le 2\sqrt{d_{max}}, K_2> \frac{K_1^2}{4} + \frac{4 d_{max}^2}{K_1^2} \right\} \cup \left\{ (K_1, K_2) \in {\mathbb {R}}^2 \mid K_1> 2\sqrt{d_{max}}, K_2> 2 d_{max} \right\}\), the system states \(x_1\) and \(x_2\) will converge to zero within fixed time \(T_0\)49.

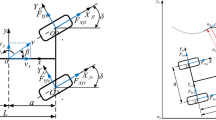

Kinematic model of four-WMR

In this section, a four-WMR with framework as shown in Fig. 1is considered. In order to design an effective control method, the kinematic model of the four-WMR is introduced following the methodology outlined in13. Parameters of the four-WMR and their notations are described in Table. 1.

The robot’s kinematic model is derived from the constraints imposed by the velocity components that can be determined as follows

The trajectory of the four-WMR in global Cartesian coordinate is represented as

Dynamic model of four-WMR

For a four-WMR, the total of the external forces and moments acting on the robot body-centered lead to the motion equations as following

where m represents the mass; \(I_z\) denotes the moment of inertia (MoI) about the z-axis; \(I_e = I_t + n^2I_m\), \(I_t\), and \(I_m\) denote the effective MoI, MoI of wheel, and MoI of motor, respectively; \(\tau _L\) and \(\tau _R\) denotes the control torque at left and right wheel, respectively; and \(n>1\) is the gear ratio.

Accurate modeling of the friction forces between the tires and the ground is crucial for developing a precise dynamics model for a WMR. Each tire of the WMR experiences two primary friction components as illustrated in Fig. 1. The longitudinal friction force acts in the direction of the tire’s rotation and is influenced by the slip ratio. The lateral friction force, on the other hand, acts perpendicular to the direction of the tire’s rotation and is influenced by the slip angle.

By eliminating the friction forces and reorganizing the dynamics equation of (5) and combining it with the kinematic models from (3) and (4), the dynamics model of the four-WMR can be described as:

where \(\Omega _u=mR^2+2I_e; \Omega _r=2b^2I_e+R^2(I_z+md^2); \tau _u= \frac{1}{2}(\tau _L+\tau _R); \tau _r= \frac{1}{2}(\tau _L-\tau _R); \delta _u=\frac{1}{\Omega _u}\left[ R^2P_x+mR^2rv^s-I_e({\dot{u}}_l^s+{\dot{u}}_r^s)\right] ;\)

\(\delta _r=\frac{1}{\Omega _r}\left[ dR^2P_y-M_dR^2-mdR^2{\dot{v}}^s-bI_e({\dot{u}}_l^s-{\dot{u}}_r^s)\right] ;\delta _x=-v^s\sin (\theta ); \delta _y=v^s\cos (\theta ).\)

In (6), the third component of left side represents the lumped uncertainties, including WSS, and external disturbances and is denoted as \(\delta _m = \left[ \begin{matrix}\delta _x\,\, \delta _y\,\, 0\,\, \delta _u\,\, \delta _r \end{matrix}\right] ^T\).

Taking time derivative of the dynamics model (6) and substituting the kinematic equations, the robot dynamics model in state space form can be obtained as following

where \(x_1 = \left[ \begin{matrix} X&Y \end{matrix}\right] ^T\), \(x_2 = \left[ \begin{matrix}{\dot{X}}&{\dot{Y}} \end{matrix}\right] ^T\), \(M(\theta )\) is a positive definite matrix, \(M(\theta ) = \left[ \begin{array}{ll} \frac{nR}{\Omega _u}\cos (\theta ) & -\frac{nRb(d+l)}{\Omega _r}\sin (\theta )\\ \frac{nR}{\Omega _u}\sin (\theta ) & \frac{nRb(d+l)}{\Omega _r}\cos (\theta )\\ \end{array}\right] ,\) \(\Upsilon ({x}_2, \theta , \delta _m) = \left[ \begin{array}{ll} -\frac{lmR^2+2(d+l)I_e}{nR}r^2\\ \frac{2b^2I_e+R^2(I_e-mdl)}{nbR(d+l)}ur\\ \end{array}\right] ,\) \(\Xi ({x}_2, \theta , \delta _m) = \left[ \begin{array}{ll} -\frac{\Omega _u}{nR}(\delta _u-v^sr)\\ \frac{\Omega _r}{nbR(d+l)}((b+l)\delta _r-{\dot{v}}^s)\\ \end{array}\right] ,\) and \(r({x}_2, \theta , \delta _m) = \frac{1}{d+l}\left[ -({\dot{X}}-\delta _x)\sin \theta + ({\dot{Y}}-\delta _y)\cos \theta \right] .\)

In simple operation conditions, it can be assumed that WSS and external disturbances are zero, the dynamics model can be rewritten as

where \(\Upsilon _0({x}_2, \theta ) = \left[ \begin{matrix} -\frac{lmR^2+2(d+l)I_e}{nR}r^2_{({x}_2, \theta )}\\ \frac{2b^2I_e+R^2(I_e-mdl)}{nbR(d+l)}u_{({x}_2, \theta )}r_{({x}_2, \theta )}\\ \end{matrix}\right] ,\ \text {and}\; r({x}_2, \theta ) = \frac{1}{d+l}(-{\dot{X}}\sin \theta + {\dot{Y}}\cos \theta ).\)

By combining (7) and (8), the robot dynamics model can be transformed as

where \(D = (M-M_0)(\theta )\left[ \tau + \Upsilon + \Xi ({x}_2, \theta , \delta _m)\right] + M(\theta )\left[ \Upsilon -\Upsilon _0 +\Xi ({x}_2, \theta , \delta _m)\right]\) denotes the lumped of WSS and external disturbances.

Error dynamics model

By defining position tracking errors \(e_1\) and velocity tracking errors \(e_2\) as

where \(x_d\) denotes assumed trajectory and \({\dot{x}}_d\) denotes assumed velocity, the four-WMR system in (9) is transferred to error dynamics as

The principal purpose of this article is to develop a control approach that effectively mitigates the adverse influences of WSS, and external disturbances in WMRs with precise tracking ability. In addition, the control method aims to keep the tracking error within predefined bounds. Without the requirement of a state observer or estimator, this novel proposed control strategy is constructed under the assumption that the position and velocity in the system are always available.

Control algorithm design

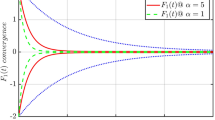

Prescribed-performance function

The PPF facilitates tracking errors within specified bounds over time. An illustration of PPC is shown in Fig. 2. Generally, PPF, \(P\left( t\right)\), relates to the tracking error and is chosen based on the following conditions

-

\(P\left( t\right)\) is a smooth function.

-

\({lim}_{t\rightarrow \infty }\ P\left( t\right) \ =\ p_\infty>0\).

-

\(P\left( t\right)\) is decreasing and positive.

The PPF is selected as45

where \(p_0\), \(p_\infty\) satisfy \(p_0> p_\infty> 0\), \(p_0> |e_1(0)|\), and \(\lambda>0\).

The ETF is a technique used in control systems to modify the error signal before it is processed by the control algorithm. Through suitable transformation function design, the system’s disturbances, uncertainties, and nonlinearities may be reduced, leading to faster convergence, improved robustness, and better stability of the controlled system. The ETF, \(\Psi \left( \xi _1\right)\) is selected based on the following conditions

-

\(\Psi \left( \xi _1\right)\) is a smooth and strictly increasing function.

-

\(-1<\Psi \left( \xi _1\right) <1\).

-

\(\Psi \left( \xi _1\right) =0\ \text {when}\ \xi _1=0\).

-

\(\left\{ \begin{matrix} {lim}_{\xi _1\rightarrow -\infty } \Psi (\xi _1)\ & =& -1\\ {lim}_{\xi _1\rightarrow +\infty } \Psi (\xi _1)\ & =& 1\\ \end{matrix} \right.\).

where \(\xi _1\) represents transformed error.

The specific ETF for this study is chosen as43

where

From the ETF (14), transformed error is produced as follows

Taking time derivative of (13), yields

where \({\dot{P}}(t) = -\lambda (p_0 - p_\infty )\textrm{exp}(-\lambda t).\)

From (16), the derivative of transformed error with respect to time is obtained as

Taking time derivative of (16), yields

where \({\ddot{P}}(t)= \lambda ^2(p_0 - p_\infty )\textrm{exp}(-\lambda t).\)

From (18), the second-order derivative of transformed error with respect to time is obtained as

where \(\Sigma =\frac{2}{\pi } \left( {\ddot{P}}(t)\arctan (\xi _1)+ \frac{2{\dot{P}}(t)\dot{\xi _1}}{1+{\xi _1}^2} - \frac{2P(t)\xi _1\dot{\xi _1}^2}{\left( 1+{\xi _1}^2\right) ^2} \right) .\)

Combining (17), (19), and (11), the dynamics model of four-WMR is transferred into

where \(\chi = \frac{\pi (1+{\xi _1}^2)}{2P(t)}>0\).

Prescribed-performance NFTSF design

To design an effective control signal, a novel prescribed-performance NFTSF is proposed based on the transformed error as follows

The term \(\Pi (\xi _1)\) is expressed as

and the term \(\Omega (\xi _1)\) is used to handle the singularity problem that is expressed as

where parameters \(\varkappa _1, \varkappa _2, \varkappa _3\) are positive constants, \(\alpha _2> 1, 0< \alpha _3 < 1\), and \(\epsilon> 0\) denote a small constant.

From the SMC theory50, when the system reaches sliding mode, the following property is obtained:

Combining (21) and (24), yields

Remark 1

The term \(\lfloor {\xi _1}\rceil ^{\alpha _3}\) with \(0< \alpha _3 < 1\) may produce singularity problem because its derivative, \(\alpha _3\left| {\xi _1}\right| ^{\alpha _3-1}\xi _2\), includes negative power of \(\xi _1\). When \(\xi _1 = 0\) and \(\xi _2 \ne 0\), this will be infinity. Thus, the use of \(\Omega (\xi _1)\) in (23) helps to avoid the singularity.

Theorem 1

Consider the sliding mode dynamics described in (25), the origin \({\xi }\) is determined as a stable equilibrium point, and the state trajectories of the system reach an arbitrarily small range, \(\epsilon\), in a limited convergence time and then converge zero exponentially.

Proof 1

To analyze the convergence of the system, we consider two cases as follows

Case 1: When \(\left| \xi _1 \right| \geqslant \epsilon\), the sliding function in (21) is represented as

The sliding mode dynamics (25) will be expressed as

Consider a Lyapunov function as following

Taking time derivative of (28) and substituting (27), yields

Denoting \(k_1 = 2\varkappa _1, k_2 = \varkappa _2 2^\frac{\alpha _2+1}{2}, \text {and} \ k_3 = \varkappa _3 2^\frac{\alpha _3+1}{2}\)

In the following, the differential (29) will be solved as

The above analysis shows that the state trajectories of the sliding mode system (25) reach a predetermined small set, \(\epsilon\), within a limited convergence time \(T_1\).

Case 2: When \(\left| \xi _1 \right| < \epsilon\), the sliding function in (21) is represented as

The sliding mode dynamics (25) will be expressed as

Using the same Lyapunov function \(V_1\) as in (28), taking its derivative and substituting (32), yields

Based on the Lyapunov stability theory, it can be concluded that the state trajectories converge to zero exponentially. Consequently, the Theorem 1 is completely demonstrated.

\(\square\)

Remark 2

The ETF in (14) is defined by \(\arctan (\xi _1)\) function, which guarantees that the position tracking error, \(e_1\), will be zero if the transformed error, \(\xi _1\), converges to zero.

Remark 3

It is noted that the linear term \(\varkappa _1 \xi _1\) in (22) helps the system to converge faster when the state of the system is very far away from the origin and weaker when the state of the system is near the origin than two nonlinear terms \(\varkappa _2 \lfloor {\xi _1}\rceil ^{\alpha _2}\) in (22) and \(\varkappa _3 \lfloor {\xi _1}\rceil ^{\alpha _3}\) in (23). When the state of the system remains at a distance from equilibrium, \(\varkappa _2 \lfloor {\xi _1}\rceil ^{\alpha _2}\) dominates over \(\varkappa _3 \lfloor {\xi _1}\rceil ^{\alpha _3}\). In contrast, when the state of the system is close to the origin, \(\varkappa _3 \lfloor {\xi _1}\rceil ^{\alpha _3}\) dominates over \(\varkappa _2 \lfloor {\xi _1}\rceil ^{\alpha _2}\). Combining of these terms guarantees a high convergence rate in the whole sliding function.

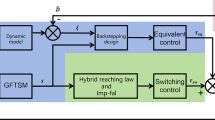

Fixed-time prescribed-performance NFTSMC design

Based on the prescribed-performance NFTSF (21), a novel FPP-NFTSMC signal is proposed as following

where \(\tau _{eq}\) represents equivalent control

and \(\tau _{sw}\) represents switching control, which is designed based on the USOSM as following

with \(\dot{\Pi }(\xi _1) = \varkappa _1 \xi _2 + \varkappa _2 \alpha _2 \left| {\xi _1}\right| ^{\alpha _2 - 1}\xi _2\); \(\dot{\Omega }(\xi _1) = \left\{ \begin{matrix} \alpha _3\left| {\xi _1}\right| ^{\alpha _3-1}\xi _2 & if & \left| \xi _1 \right| \geqslant \epsilon \\ \epsilon ^{\alpha _3-1} \xi _2 & if & \left| \xi _1 \right| < \epsilon \\ \end{matrix}\right.\); \(\beta _1\), and \(\beta _2\) denote positive constants and are selected based on Lemma 1. The functions \(\Gamma _1(\sigma )\), and \(\Gamma _2(\sigma )\) are described as

where \(\gamma> 0\) represents a constant.

Theorem 2

Suppose that the derivative of lumped of WSS and external disturbances D in the four-WMR (9) is bounded as

where \(D_{max}\) is a positive constant.Then, if the control input is designed as in (34), (35), and (36) with suitably chosen parameters, the stability of the robot system is guaranteed and the sliding surface converges to zero within fixed-time.

Proof 2

Taking time derivative of the proposed sliding function (21), yields

Combining the transformed error dynamics (20), with control signals in ((34), (35), and (36)) and substituting into (39), yields

By denoting \(\vartheta _1 = \vartheta + D\), the system (40) can be rewritten as

The form of (41) is in the same form of (1) in Lemma 1; accordingly, it can be concluded that the sliding surface \(\sigma\) will converge to zero within fixed-time \(T_0\)49. Thus, the Theorem 2 is fully proven. \(\square\)

Therefore, the settling time is determined as \(T_s = T_0 + T_1\).

The block diagram of the proposed FPP-NFTSMC is presented in Fig. 3.

Results and discussions

Simulation setup

To validate the powerfulness of the proposed algorithm, simulations are performed to manage the WMR system under two operational scenarios: 1) following a straight trajectory and 2) following a U-shaped path. By simulating various scenarios and disturbances, we aim to thoroughly evaluate the tracking ability and robustness of the WMR. For computer simulations, MATLAB/Simulink is used where the sampling time is 1 ms. The WMR’s parameters are detailed in Table 2. The control parameters are selected by the trial-and-error approach to obtain suitable performance and their values are outlined in Table 3 ( with \({\bar{D}}\) is defined in Appendices).

Case 1: In this case, the WMR is tasked with tracking a straight trajectory, depicted in Fig. 8. The trajectory consists of three separate phases that follow a predetermined velocity profile:

-

The WMR undergoes a phase of constant acceleration, steadily increasing its velocity from an initial value to a specified maximum velocity,

-

The WMR maintains the constant maximum velocity,

-

The WMR enters a phase of constant deceleration, gradually reducing the velocity to zero.

According to the three operation phases, the trajectory of the WMR is assumed as:

The initial position is assumed as \(\left[ \begin{matrix}x&y&\theta \end{matrix}\right] ^T = \left[ \begin{matrix}1.1&1.1&0 \end{matrix}\right] ^T\). In the context of tracking a straight-line trajectory, the robot’s wheel skidding is not considered a significant factor, which implies that the skidding velocity \(v^s\) is effectively zero \((0\ \mathrm {m/s})\). The wheel slipping is assumed as simple sinusoidal function

The expected external disturbances are as \(P_x=10 (\textrm{N})\), and \(P_y=10 (\textrm{N})\).

Case 2: The objective of this scenario is to assess how well the suggested control approach compensates for WSS and external disturbances while following a difficult U-shaped trajectory, as shown in Fig. 14. The trajectory poses a challenging situation where abrupt wheel sliding motion could happen, requiring strong control systems to keep tracking accuracy and stability.

The trajectory is divided into three separate phases:

-

In the first stage, the four-WMR accelerates to reach a set velocity along a straight line; therefore, only the influences of wheel slipping on the robot are under consideration.

-

When WMR reaches the turning spot, it makes a U-turn to follow the trajectory’s curving course. WSS effects are taken into account since this phase necessitates synchronized motion control to safely handle the steep turn while preserving stability and adherence to the intended trajectory.

-

The robot executes a U-turn, then slows down and travels straight ahead to the intended location. Like the first phase, only the effects of wheel slipping are taken into account.

The expected trajectory is as follows

The WMR’s initial position is assumed as \(\left[ \begin{matrix}x&y&\theta \end{matrix}\right] ^T = \left[ \begin{matrix}1.1&1.1&0 \end{matrix}\right] ^T\).

The assumed wheel skidding of WMR is

The assumed WMR’s wheel slipping is

The expected external disturbances are as

Simulation results

To verify the control performance of the proposed FPP-NFTSMC, a comparison to three other controllers: 1) the conventional SMC, which is designed in (50); 2) an NFTSMC with selected sliding function as in29 and the control signal is described in (55); and 3) a fixed-time NFTSMC with selected sliding function as in51 and the control signal is described in (60); is performed.

In Case 1, the position tracking errors are illustrated in Fig. 4. Overall, all four control methods provide good tracking performance when the robot is under the influence of wheel slipping. The result shows that the convergence speeds of SMC and NFTSMC are slower than those of fixed-time NFTSMC and the proposed FPP-NFTSMC. Further, the proposed FPP-NFTSMC provides tracking errors with the fastest convergence rate. Regarding the tracking performance, the chattering phenomenon, which will be shown in Fig. 7, affects the tracking results of SMC, NFTSMC, and fixed-time NFTSMC; specifically, they appear with a little chattering effect. Among the controllers, the conventional SMC provides the lowest tracking performance and the fixed-time NFTSMC provides the closest result to the proposed FPP-NFTSMC. The proposed FPP-NFTSMC, in the red solid line, obtains a smooth tracking error with the highest tracking performance. The results of velocity tracking are presented in Fig. 5. Unlike position tracking, the velocity tracking errors of SMC, NFTSMC, and fixed-time NFTSMC are highly affected by the chattering phenomenon in the control signals (see Fig. 7). Thanks to the application of the USOSM algorithm in switching control law, the proposed FPP-NFTSMC provides smooth control input; therefore, it achieves the highest velocity tracking results. To simplify the comparison, in terms of sliding function and control input, we focus on comparing the results of the proposed FPP-NFTSMC and fixed-time NFTSMC. As shown in Fig. 6, the proposed prescribed performance NFTSF reaches the convergence stage quickly with a low chattering effect. Results of control input signals are illustrated in Fig. 7. As in Fig. 7a, the control input of fixed-time NFTSMC has a high chattering phenomenon. On the contrary, the proposed FPP-NFTSMC in Fig. 7b, with a smooth switching control law, provides control input with a low chattering effect. In Fig. 8, the assumed trajectory and tracking results are presented.

In Case 2, Fig. 9 shows the result of position tracking error. Similar to Case 1, the proposed FPP-NFTSMC provides the best control performance with the highest tracking performance and fastest convergence speed. Especially, the proposed control algorithm maintains the tracking ability when wheel skidding occurs, demonstrating robustness. In this part, a small comparison with different initial values is added to show the fast convergence characteristic of the proposed FPP-NFTSMC. In Fig. 9, with the initial value \(\left[ \begin{matrix}x&y&\theta \end{matrix}\right] ^T = \left[ \begin{matrix}1.1&1.1&0 \end{matrix}\right] ^T\), the convergence time is around 0.73 seconds. In Fig. 10, when changing the initial value to \(\left[ \begin{matrix}x&y&\theta \end{matrix}\right] ^T = \left[ \begin{matrix}1.4&1.4&0 \end{matrix}\right] ^T\), the convergence time of SMC and NFTSMC become bigger and exceed 2 seconds. In contrast, the proposed FPP-NFTSMC maintains the convergence process and reaches the convergence state after 0.94 seconds. Fig. 11 illustrates the velocity tracking performance. As shown in the result, the velocity tracking errors of the SMC, NFTSMC, and fixed-time NFTSMC are influenced by the chattering issues of the control signal. On the other side, the proposed FPP-NFTSMC offers the highest velocity tracking accuracy with a low chattering phenomenon. The results sliding surface is shown in Fig. 12, where the proposed prescribed performance NFTSF can reach the convergence stage rapidly at both the initial time and the time that wheel skidding occurs. According to the control input signal results, the fixed-time NFTSMC provides control input with a high chattering phenomenon as in Fig. 13a. Otherwise, by using the USOSM algorithm, the proposed FPP-NFTSMC offers the control signal with low chattering phenomenon as in Fig. 13b. Fig. 14 shows the results of tracking the assumed U-shaped trajectory. The results in both cases are similar, showing the effectiveness of the proposed FPP-NFTSMC and adaptability to various working conditions.

Conclusions

This paper proposed a novel SMC tactic for WMRs under the influence of WSS, and external disturbances. Using the advantages of each technique, a unique prescribed-performance NFTSF is first presented by combining the NFTSMC and transformed error. The proposed prescribed-performance NFTSF and the USOSM algorithm serve as the foundation for the proposal of a novel FPP-NFTSMC. Thanks to the utilizing of the USOSM algorithm, the proposed FPP-NFTSMC provides a smooth control signal, thereby overcoming the common chattering problem in SMC. The suggested approach provides remarkable tracking performance, including low tracking error, quick convergence, robustness against WSS and external disturbances, decreased chattering phenomenon, and ensuring tracking errors remain within bounds. The stability and fixed-time convergence of the overall system are demonstrated using the Lyapunov function. Finally, the efficiency of the suggested FPP-NFTSMC is validated through simulations.

Data availibility

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Suresh, K., Venkatesan, R. & Venugopal, S. Mobile robot path planning using multi-objective genetic algorithm in industrial automation. Soft Computing 26, 7387–7400 (2022).

Fragapane, G., Hvolby, H.-H., Sgarbossa, F. & Strandhagen, J. O. Autonomous mobile robots in sterile instrument logistics: an evaluation of the material handling system for a strategic fit framework. Production Planning & Control 34, 53–67 (2023).

Kriegel, J., Rissbacher, C., Reckwitz, L. & Tuttle-Weidinger, L. The requirements and applications of autonomous mobile robotics (amr) in hospitals from the perspective of nursing officers. International Journal of Healthcare Management 15, 204–210 (2022).

Lu, Z., Liu, Z., Correa, G. J. & Karydis, K. Motion planning for collision-resilient mobile robots in obstacle-cluttered unknown environments with risk reward trade-offs. In 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 7064–7070 (IEEE) (2020).

Shafaei, S. M. & Mousazadeh, H. Development of a mobile robot for safe mechanical evacuation of hazardous bulk materials in industrial confined spaces. Journal of Field Robotics 39, 218–231 (2022).

Vu, M. T. et al. Analytical solution of time-optimal trajectory for heaving dynamics of hybrid underwater gliders. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 11, 2216 (2023).

Tran, X.-T., Nguyen, V.-C., Le, P.-N. & Kang, H.-J. Observer-based fault-tolerant control for uncertain robot manipulators without velocity measurements. Actuators 13, https://doi.org/10.3390/act13060207 (2024).

Boukattaya, M., Mezghani, N. & Damak, T. Computed-torque control of a wheeled mobile manipulator. Int J Robot Eng 3, 1–6 (2018).

Nguyen, V.-C. & Kang, H.-J. A fault tolerant control for robotic manipulators using adaptive non-singular fast terminal sliding mode control based on neural third order sliding mode observer. In Huang, D.-S. & Premaratne, P. (eds.) Intelligent Computing Methodologies, 202–212 (Springer International Publishing, Cham) (2020).

Wang, W., Huang, J., Wen, C. & Fan, H. Distributed adaptive control for consensus tracking with application to formation control of nonholonomic mobile robots. Automatica 50, 1254–1263 (2014).

Hou, Z.-G., Zou, A.-M., Cheng, L. & Tan, M. Adaptive control of an electrically driven nonholonomic mobile robot via backstepping and fuzzy approach. IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology 17, 803–815 (2009).

Truong, T. N., Vo, A. T. & Kang, H.-J. Neural network-based sliding mode controllers applied to robot manipulators: A review. Neurocomputing 562, 126896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2023.126896 (2023).

Hoang, N.-B. & Kang, H.-J. Neural network-based adaptive tracking control of mobile robots in the presence of wheel slip and external disturbance force. Neurocomputing 188, 12–22 (2016).

Yang, J.-M. & Kim, J.-H. Sliding mode control for trajectory tracking of nonholonomic wheeled mobile robots. IEEE Transactions on robotics and automation 15, 578–587 (1999).

Nguyen, V.-C., Tran, X.-T. & Kang, H.-J. A novel high-speed third-order sliding mode observer for fault-tolerant control problem of robot manipulators. In Actuators, vol. 11, 259 (MDPI) (2022).

Ahmed, S. & Azar, A. T. Adaptive fractional tracking control of robotic manipulator using fixed-time method. Complex & Intelligent Systems 10, 369–382 (2024).

Li, J., Wang, J., Peng, H., Hu, Y. & Su, H. Fuzzy-torque approximation-enhanced sliding mode control for lateral stability of mobile robot. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems 52, 2491–2500 (2021).

Sun, C., Wang, S. & Yu, H. Finite-time sliding mode control based on unknown system dynamics estimator for nonlinear robotic systems. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems II: Express Briefs 70, 2535–2539 (2023).

Nguyen, V.-C., Vo, A.-T. & Kang, H.-J. A finite-time fault-tolerant control using non-singular fast terminal sliding mode control and third-order sliding mode observer for robotic manipulators. IEEE Access 9, 31225–31235. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3059897 (2021).

Chen, Q., Ye, Y., Hu, Z., Na, J. & Wang, S. Finite-time approximation-free attitude control of quadrotors: Theory and experiments. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems 57, 1780–1792 (2021).

Xuan-Mung, N. et al. Novel gain-tuning for sliding mode control of second-order mechanical systems: theory and experiments. Scientific Reports 13, 10541 (2023).

Wu, L., Liu, J., Vazquez, S. & Mazumder, S. K. Sliding mode control in power converters and drives: A review. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 9, 392–406 (2021).

Benaziza, W., Slimane, N. & Mallem, A. Mobile robot trajectory tracking using terminal sliding mode control. In 2017 6th International Conference on Systems and Control (ICSC), 538–542 (IEEE) (2017).

Yu, X. & Zhihong, M. Fast terminal sliding-mode control design for nonlinear dynamical systems. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Fundamental Theory and Applications 49, 261–264 (2002).

Mobayen, S. Fast terminal sliding mode controller design for nonlinear second-order systems with time-varying uncertainties. Complexity 21, 239–244 (2015).

Li, C. et al. Non-singular terminal sliding mode control of an omnidirectional mobile manipulator based on extended state observer. International Journal of Intelligent Robotics and Applications 5, 219–234 (2021).

Tran, M.-D., Kang, H.-J. et al. Nonsingular terminal sliding mode control of uncertain second-order nonlinear systems. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2015 (2015).

Nguyen, V.-C., Vo, A.-T. & Kang, H.-J. A non-singular fast terminal sliding mode control based on third-order sliding mode observer for a class of second-order uncertain nonlinear systems and its application to robot manipulators. IEEE Access 8, 78109–78120 (2020).

Sun, Z. et al. Fuzzy adaptive recursive terminal sliding mode control for an agricultural omnidirectional mobile robot. Computers and Electrical Engineering 105, 108529 (2023).

Nguyen, V.-C., Le, P.-N. & Kang, H.-J. An active fault-tolerant control for robotic manipulators using adaptive non-singular fast terminal sliding mode control and disturbance observer. In Actuators, vol. 10, 332 (MDPI), (2021).

Ahmed, S., Azar, A. T. & Ibraheem, I. K. Nonlinear system controlled using novel adaptive fixed-time smc. AIMS Mathematics 9, 7895–7916 (2024).

Pazooki, M. & Mazinan, A. Hybrid fuzzy-based sliding-mode control approach, optimized by genetic algorithm for quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicles. Complex & Intelligent Systems 4, 79–93 (2018).

Chen, H., Tang, G., Wang, S., Guo, W. & Huang, H. Adaptive fixed-time backstepping control for three-dimensional trajectory tracking of underactuated autonomous underwater vehicles. Ocean Engineering 275, 114109 (2023).

Truong, T. N., Vo, A. T. & Kang, H.-J. A model-free terminal sliding mode control for robots: Achieving fixed-time prescribed performance and convergence. ISA Transactions 144, 330–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isatra.2023.11.013 (2024).

Ahmed, S., Azar, A. T. & Ibraheem, I. K. Model-free scheme using time delay estimation with fixed-time fsmc for the nonlinear robot dynamics. AIMS Mathematics 9, 9989–10009 (2024).

Labbadi, M., Boubaker, S., Djemai, M., Mekni, S. K. & Bekrar, A. Fixed-time fractional-order global sliding mode control for nonholonomic mobile robot systems under external disturbances. Fractal and Fractional 6, 177 (2022).

Gohari, H., Zarastvand, M., Talebitooti, R., Loghmani, A. & Omidpanah, M. Radiated sound control from a smart cylinder subjected to piezoelectric uncertainties based on sliding mode technique using self-adjusting boundary layer. Aerospace Science and Technology 106, 106141 (2020).

Suryawanshi, P. V., Shendge, P. D. & Phadke, S. B. A boundary layer sliding mode control design for chatter reduction using uncertainty and disturbance estimator. International Journal of Dynamics and Control 4, 456–465 (2016).

Levant, A. Higher-order sliding modes, differentiation and output-feedback control. International journal of Control 76, 924–941 (2003).

Mousavi, Y., Bevan, G., Kucukdemiral, I. B. & Fekih, A. Observer-based high-order sliding mode control of dfig-based wind energy conversion systems subjected to sensor faults. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications (2023).

Saied, H., Chemori, A., Bouri, M. & El Rafei, M. & Francis, C (Application to pkms. IEEE Transactions on Robotics, Feedforward super-twisting sliding mode control for robotic manipulators, 2023).

Boubaker, S., Labbadi, M. & Alsubaei, F. S. A generalized supertwisting algorithm based on terminal sliding manifold control of perturbed unicycle mobile robots. IEEE Access (2024).

Vo, A. T., Truong, T. N. & Kang, H.-J. Fixed-time rbfnn-based prescribed performance control for robot manipulators: Achieving global convergence and control performance improvement. Mathematics 11, 2307 (2023).

Huang, J.-T. & Chiu, C.-K. Adaptive fuzzy sliding mode control of omnidirectional mobile robots with prescribed performance. Processes 9, 2211 (2021).

Tran, X.-T. & Oh, H. Prescribed performance adaptive finite-time control for uncertain horizontal platform systems. ISA transactions 103, 122–130 (2020).

Bechlioulis, C. P. & Rovithakis, G. A. Robust adaptive control of feedback linearizable mimo nonlinear systems with prescribed performance. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control 53, 2090–2099 (2008).

Zhou, Z.-G., Zhou, D., Shi, X.-N., Li, R.-F. & Kan, B.-Q. Prescribed performance fixed-time tracking control for a class of second-order nonlinear systems with disturbances and actuator saturation. International Journal of Control 94, 223–234 (2021).

Vo, A. T., Truong, T. N. & Kang, H.-J. A model-free-based control method for robot manipulators: Achieving prescribed performance and ensuring fixed time stability. Applied Sciences 13, 8939 (2023).

Cruz-Zavala, E., Moreno, J. A. & Fridman, L. M. Uniform robust exact differentiator. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control 56, 2727–2733 (2011).

Utkin, V. I. Sliding modes in control and optimization (Springer Science & Business Media), (2013).

Hu, Y., Yan, H., Zhang, H., Wang, M. & Zeng, L. Robust adaptive fixed-time sliding-mode control for uncertain robotic systems with input saturation. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics 53, 2636–2646 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by the MSIT (Ministry of Science and ICT), Korea, under the ICAN (ICT Challenge and Advanced Network of HRD) program (IITP-2024-RS-2022-00156345) supervised by the IITP (Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation). This work was partly supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant (No. RS-2023-00219051 and RS-2023-00209107) and by Unmanned Vehicles Core Technology Research and Development Program through the NRF and Unmanned Vehicle Advanced Research Center (UVARC), funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT, the Republic of Korea (NRF-2023M3C1C1A01098408).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, visualization, and data curation, V.C.N.; writing-original draft preparation, and writing-review and editing, V.C.N., and S.H.K.; supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition, S.H.K. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendices

To design the compared control algorithms, the lumped of WSS and external disturbances D is assumed to be bounded as

where \({\bar{D}}\) is a positive constant.

SMC design

Consider the four-WMR (9) with tracking errors defined in (10), the conventional linear sliding surface is selected as

where \(c> 0\) denotes a constant.

The SMC signal is designed as follows

where \(\mu>0\) denotes a small constant.

NFTSMC design

Consider the four-WMR (9) with tracking errors defined in (10), a NFTSF is chossen as29

where \(\kappa _1, \text {and}\ \kappa _2> 0\), and \(1<\nu _1<2\).

A recursive integral terminal sliding function is designed as

where \(\dot{s}_I = \lfloor {s}\rceil ^{\nu _2}\), \(\kappa _3>0\), and \(0<\nu _2<1\).

The NFTSMC signal is designed as following

where \(\mu>0\).

Fixed-time NFTSMC design

Consider the four-WMR (9) with tracking errors defined in (10), a NFTSF is chossen as51

The term \(\Omega (e_1)\) is used to handle the singularity problem that is expressed as

where parameters \(\kappa _2, \kappa _3\) are positive constants, \(\nu _2> 1, 0< \nu _3 < 1\), and \(\epsilon\) denotes a small positive constant.

The fixed-time NFTSMC signal is designed as following

where \(\kappa>0,\ 0<\nu <1,\ \mu>0\) and \(\dot{\Omega }(e_1) = \left\{ \begin{matrix} \nu _3\left| {e_1}\right| ^{\nu _3-1}e_2 & if & \left| e_1 \right| \geqslant \epsilon \\ \epsilon ^{\nu _3-1} e_2 & if & \left| e_1 \right| < \epsilon \\ \end{matrix}\right.\).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nguyen, VC., Kim, S.H. A novel fixed-time prescribed performance sliding mode control for uncertain wheeled mobile robots. Sci Rep 15, 5340 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89126-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89126-6