Abstract

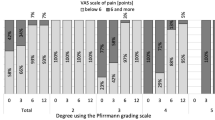

In the lumbar discectomy, an annular suture faces challenges when annular defects are located at the attachment area of the fibrous annulus at the edge of the vertebral body. In this study, a novel bone-anchoring annular suture technique was proposed to close this type of defect. Finally, the clinical efficacy of this suture technique was investigated. A total of 84 patients with lumbar intervertebral disc herniation who underwent arthroscopic-assisted uni-portal spinal surgery and novel bone-anchoring annular sutures were selected. Clinical and imaging outcomes were compared before and after surgery, including the visual analog scale (VAS) for back and leg, Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) score, Oswestry disability index (ODI), disc height, and the Pfirrmann grade of the disc. The average follow-up time was 12.6 ± 0.9 months. Over time, the VAS (low back pain and leg pain) and ODI scores of patients decreased significantly (P < 0.05), while the JOA scores increased significantly (P < 0.05). At the last follow-up, the excellent and good rate was 91.7% according to the modified MacNab criteria. No significant difference between the preoperative and postoperative disc height and Pfirrmann grade was observed (P > 0.05). No reoperation cases were observed during the follow-up period. The novel bone-anchoring annular suture technique showed good safety and preliminary efficacy for annular defects that occur at the attachment area of the fibrous annulus at the edge of the vertebral body.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Currently, the lumbar discectomy is a commonly utilized method for treating lumbar intervertebral disc herniation (LDH), yielding favorable clinical outcomes1,2. However, it is imperative to cut open the annulus fibrosus or extract the protruding nucleus pulposus via the existing defects in the annulus fibrosus3,4. Disruption of the structural integrity of the annulus fibrosus diminishes its mechanical properties, accelerates intervertebral disc degeneration, and further increases the risk of residual nucleus pulposus herniation5,6. The study of Miller et al. showed that the risk of symptom recurrence and reoperation following lumbar discectomy is higher in patients with large annular defects (≥ 6 mm)7. Literature reported a recurrence rate between 2% and 18% following simple lumbar discectomy8,9. It is estimated that about 10% of patients require secondary surgery due to postoperative recurrence10,11. To prevent the recurrence of LDH, surgeons remove as much of the nucleus pulposus as possible, leading to faster intervertebral disc height loss12. Therefore, the restoration of the integrity of the annulus fibrosus holds significant clinical importance in the prevention of LDH recurrence and the restructuring of the surrounding nerve environment13.

As early as 1977, some scholars proposed that suturing the annulus fibrosus during lumbar discectomy could help prevent LDH recurrence. Subsequent research has shown that annulus fibrosus suture can effectively prevent the nucleus pulposus leakage, preserve disc height, and facilitate the annulus fibrosus healing, thereby reducing the rates of recurrence and reoperation for LDH6,14,15,16. The advent of spinal endoscopy has led to advancements in annulus fibrosus suture techniques, allowing for suturing under various surgical procedures, such as microendoscopic discectomy, percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy, and unilateral biportal endoscopy (UBE)17,18,19. However, although these annular repair techniques have shown promise in reducing recurrence rates of LDH, they often face challenges when addressing annular defects at the attachment area of the fibrous annulus at the vertebral edge. This is primarily because existing suture techniques mainly target incisions or defects at the middle part of the fibrous annulus, with the anchors located solely on the annulus itself. For defects at the vertebral edge, anchoring and suturing only on the annulus make it difficult to securely close the defect. Clinically, this often results in unsatisfactory suture outcomes, leading many surgeons to abandon the suturing process20.

To address the above problems, we introduced a novel annular suture technique based on the bone anchoring method. This technique draws from the concept of footprint reconstruction in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair and proposes footprint healing for annular defects located at the attachment area of the fibrous annulus at the edge of the vertebral body21. Unlike previous annular suture methods that anchor solely on the fibrous annulus, the bone anchoring method directly establishes an anchor within the vertebral body, connecting with an anchor on the fibrous annulus to tightly close the defect.

In this study, a retrospective analysis was conducted to examine the clinical efficacy of the novel bone-anchoring annular suture technique in the treatment of LDH among patients who underwent arthroscopic-assisted uni-portal spinal surgery (AUSS), namely uni-portal non-coaxial spinal endoscopic surgery (UNSES).

Methods

Subjects

A total of 84 patients with single-segment LDH who underwent AUSS and novel bone-anchoring annular sutures in our hospital from September 2021 to January 2023 were selected. An informed consent form was completed by all patients before surgery, and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the hospital. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) single-segment disc herniation confirmed by radicular symptoms and radiographic presentation (CT and MRI); (ii) poor outcome after regular conservative treatment for more than 3 months; (iii) age 18–75 years. Exclusion criteria included: (i) disc calcification; (ii) lumbar instability or spondylolisthesis; (iii) severe degeneration of the intervertebral discs; (iv) endplate inflammation with Modic change greater than type 2; (v) spinal infections, tumors, and fractures; and (vi) BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2. All patients included in this study had no history of previous spinal surgeries. Additionally, none of the patients were diagnosed with coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, psychiatric disorders, or infectious diseases. There was also no reported family history of genetic disorders among the study population.

AUSS technique

The AUSS technique was described in our previous studies22. It is an improved version of the UBE technique. It consolidates the unilateral dual-channel double holes of UBE into a single hole, allowing for independent and unrestricted operation of both the endoscope and instruments within a single hole. An open observation field under a 30° arthroscope, a free operation space, and compatibility with many spinal surgery instruments and techniques make it ideal for spinal surgery. Specifically, the patient was placed in the prone position after general anesthesia. The responsible segment was determined under C-arm fluoroscopy. A 1.5–2.0 cm incision was made along a line connecting the midpoint of the upper and lower pedicles, parallel to the midline of the spinous process at the level of the intervertebral space. The dilation tube was used to enlarge the passage, allowing for the insertion of the working trocar and endoscope. A grinding drill was used to grind off part of the laminae and articular processes. Then the ligamentum flavum was removed. Upon entering the spinal canal, the intervertebral disc, dural sac, and nerve root were visualized, followed by the removal of the protruded nucleus pulposus. Subsequently, an annuloplasty was performed and the annular defect was sutured. After adequate hemostasis, the dural sac, and nerve root were explored, and the incision was sutured.

Bone-anchoring annular suture technique

The schematic illustration for the bone-anchoring annular suture technique is presented in Fig. 1. Three bone-anchoring suture techniques were developed, including X-shaped suture (Fig. 2), parallel suture (Fig. 3), and triangular-shaped suture (Fig. 4). To maximize closure effectiveness, we utilized an individualized approach to suturing depending on the type, size, shape, and location of the annular defect, as well as the quality of the surrounding annular tissue. The Smile annular suture device (2020 Medical Technology Company, Beijing, China) was used in this study. This suture device has not been widely adopted in clinical practice; therefore, surgeons should ensure they are thoroughly proficient in its operation.

Schematic illustration of the bone-anchoring annular suture technique. (A) Insertion of a 2.0 mm Kirschner wire into the vertebral body to create a hole. (B) Introduction of the first stitch into the hole to establish the bone anchor. (C) The suture of the bone anchor is threaded through the coil of the second stitch externally, followed by penetration of the stitch through the annulus to complete the second fixed anchor. (D,E) The knot is tied and subsequently pushed into the annulus fibrosus using a knot pusher. (F) The free end of the suture is trimmed.

The surgical procedure of the X-shaped bone-anchoring annulus fibrosus suture technique under arthroscopic-assisted uni-portal spinal surgery. (A) Exposure of the protruding nucleus pulposu. (B) Excision of the nucleus pulposus reveals the damaged annulus fibrosus. (C) Penetration of the first stitch into the inferior vertebral body. (D,E) Penetration of the second stitch at the lateral section of the annulus fibrosus and tightening with the first stitch to tie a square knot. (F–H) Anchor the first stitch diagonally to one side of the vertebral body and then sew another stitch. (I) No visible compression of the nerve root after suturing.

The surgical procedure of the parallel 2-stitch bone-anchoring annulus fibrosus suture technique under arthroscopic-assisted uni-portal spinal surgery. (A) Exposure of the protruding nucleus pulposus (N indicates the traversing nerve root). (B) Excision of the nucleus pulposus reveals the damaged annulus fibrosus and the annulus fibrosus is broken on one side adjacent to the inferior vertebral body. (C) Penetration of the first stitch into the inferior vertebral body. (D,E) Penetration of the second stitch at the lateral section of the annulus fibrosus and tightening with the first stitch to tie a square knot. (F–H) Repeat the above operation to tie another knot. (I) Cutting the two parallel stitches after knotting.

The surgical procedure of the triangular-shaped bone-anchoring annulus fibrosus suture technique under arthroscopic-assisted uni-portal spinal surgery. (A) Exposure of the protruding nucleus pulposus. (B) Excision of the nucleus pulposus reveals the damaged annulus fibrosus and a bone tunnel was drilled into the inferior vertebral body. (C,D) Penetration of the first stitch into the inferior vertebral body and tightening of the broken annulus fibrosus with the first stitch. (E) Penetration a second stitch on the broken fiber ring. (F,G) Tightening the knot with the previous suture from the previous bone tunnel. (H,I) Cutting the two stitches after knotting and no visible compression of the nerve root after suturing.

For the X-shaped suture, two parallel holes were made using 2.0 Kirschner wire at the vertebral body 4 mm away from the defect. The distance between the two holes was approximately 3 mm. The first Smile stitch was punctured into the vertebral body through a hole to finish the first bone anchor. Then, the suture of the bone anchor thread through the coil of another stitch externally. Later, the stitch penetrated the annulus arthroscopically 2–3 mm from the edge of the annulus fibrosus defect to place another fixed anchor. The first knot was tied naturally, and two suture knots were tied and pushed into the annulus fibrosus with a knot pusher subsequently. The free end of the suture was cut. Similarly, the second Smile stitch was punctured into the vertebral body through another hole to finish the second bone anchor. The remaining steps were the same as before. The distance between the two puncture points at the annulus fibrosus was also approximately 3 mm. Finally, a cross-suture among the two bone anchors and two annular anchors was performed to form an X-shaped suture. The process of the parallel suture was similar to that of the X-shaped suture. The difference was that a parallel suture among the two bone anchors and two annular anchors was performed.

For the triangular-shaped suture, only one hole was made at the vertebral body. After completing the first stitching, the second Smile stitch punctured into the same hole, and another bone anchor was formed at the same position. The other steps were the same as above. Finally, a hole and two annular anchors formed a triangular-shaped suture.

Postoperative management

NSAIDs and detumescent drugs were used correctly post-surgery. After anesthetic resuscitation, patients were encouraged to start straight leg raising exercises to prevent nerve root adhesion. Patients were also instructed to utilize a waist girdle for the following four weeks in order to mitigate excessive bending and strain on the lumbar region. No bending, strenuous activity, or hard work allowed for 3 months post-operation.

Outcome assessment

Surgical time, intraoperative blood loss, incision length, and length of stay were recorded. The Visual analog scale (VAS) for back and leg, Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA)score, and Oswestry disability index (ODI) were assessed at a preoperative period and postoperatively at 3 days, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months. At the final follow-up, the postoperative outcome was assessed using the modified MacNab criteria. Moreover, disc height was measured, and the Pfirrmann grade of the disc was evaluated. Postoperative complications, LDH recurrence, and reoperation were also recorded.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS 25.0 statistical software (SPSS Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical variables were grouped and expressed as numerical values and continuous data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. For VAS, ODI, and JOA scores at a preoperative period and postoperatively at 3 days, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months, a One-way analysis of variance was used. For disc height at a preoperative period and postoperatively at 12 months, a paired t-test was used. Pfirrmann grades of the disc were compared using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

In this study, 84 patients with single segmental LDH were treated with AUSS combined with bone-anchoring annular suture (Table 1). All patients successfully completed the operation. There were 40 males and 44 females, aged 29–64 years, with an average age of 46.6 ± 8.6 years, a BMI of 23.6 ± 2.0 kg/m2, and a medical history of 11.9 ± 6.5 weeks. Moreover, there were 39 patients at the L4/5 segment, 36 at the L5/S1 segment, and 9 at the L3/4 segment.

There were 37, 26, and 21 patients who received the X-shaped, parallel, and triangular-shaped suture techniques, respectively. The average operation time, intraoperative blood loss, incision length, and hospital stay were 64.4 ± 9.9 min, 39.4 ± 9.6 ml, 1.8 ± 0.3 cm, and 5.7 ± 1.3 days, respectively. There were no serious complications such as macrovascular injury, nerve root injury, dural sac injury, and so on. 7 cases experienced postoperative sensory abnormalities in the affected limb. The symptoms were fully resolved with conservative management, including physical therapy, detumescence, and neurotrophic therapy, within an average duration of 4–6 weeks. There were no complications such as infection and thrombus after the operation.

The average follow-up time was 12.6 ± 0.9 months. Over time, the VAS (low back and leg pain) and ODI scores of patients decreased significantly (P < 0.05), while the JOA scores increased significantly (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5). At the last follow-up, according to the modified MacNab criteria, the results were excellent in 56 cases, good in 21 cases, and medium in 7 cases, with an excellent and good rate of 91.7% (Table 2).

JOA Japanese Orthopaedic Association, ODI Oswestry disability index, VAS visual analog scale.

Compared with that before the operation, the height of intervertebral space decreased 1 year after the operation, but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.070). No significant difference between the preoperative and postoperative Pfirrmann grade of the disc was observed (P = 0.437). One case showed imaging recurrence post-operation but had no clinical symptoms and did not receive additional treatment. No reoperation cases were observed during the follow-up period. Figure 6 shows preoperative and postoperative follow-up MRI images of patients with LDH, indicating no recurrence after one year of follow-up.

Preoperative and follow-up lumbar MRIs of the patient using bone-anchor suture technique. (A) Indicates the preoperative sagittal and axial MRIs, showing L4/5 herniation with spinal cord compression. (B) To avoid the artifact signal of spinal cord edema in immediate postoperative MRI examination, MRI re-examined at three-month follow-up indicates the spinal cord and nerve root were decompressed. (C) indicates the lumbar MRIs at one-year follow-up.

Discussion

The structural integrity of the annulus fibrosus plays a significant role in the recurrence of nucleus pulposus protrusion following discectomy23. Currently, there is a growing interest among scholars in the suture technology of the annulus fibrosus, which demonstrates significant potential for application in minimally invasive spinal surgery24. Existing techniques, such as percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy combined with annular suture and microendoscopic discectomy combined with annular suture, primarily target defects located in the middle part of the fibrous annulus3,14,15. These techniques anchor exclusively within the annulus fibrosus itself, which facilitates suturing because of the relatively soft annular tissue. However, their application becomes challenging when addressing annular defects at the vertebral edge. Establishing a stable anchor within the vertebral body requires additional mechanical strength, which traditional suturing devices often lack. Furthermore, the complexity of performing bone anchoring under limited visibility and constrained operating spaces increases the risk of nerve damage. Therefore, these techniques are less suitable for treating annular defects at the vertebral edge.

In this study, we draw lessons from the concept of footprint reconstruction in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair and propose footprint healing for annular defects located at the attachment area of the fibrous annulus at the edge of the vertebral body. We employ Kirschner wires and high-strength suture devices to establish robust anchors directly within the vertebral body. The findings indicated that the combination of the AUSS technique and the bone-anchoring annulus suture technique yielded a satisfactory clinical outcome, with no instances of recurrence observed throughout the follow-up period. This technique provides a viable and effective method for repairing annular defects at the edge of the vertebral body.

During a discectomy procedure, the incision of the annulus fibrosus or the rupture of the fibrous annulus prior to surgery can compromise the structural integrity of the annulus fibrosus and result in a deterioration of its biomechanical characteristics25. This will not only increase the probability of recurrence of nucleus pulposus herniation in the short term but also accelerate the speed of long-term intervertebral disc degeneration. Furthermore, the leakage of inflammatory mediators into the spinal canal through defects can lead to chemical radiculitis26. Additionally, the rough rupture of the fibrous annulus may persistently irritate the nerve root during its movement post-operation, causing postoperative pain and abnormal sensations in the corresponding nerve control region27. In order to prevent re-protrusion of the nucleus pulposus, it is common practice to remove as much of the nucleus pulposus tissue as possible during surgery28. However, this approach may not only expedite the reduction in disc height but also exacerbate the injury to the annulus fibrosus.

Therefore, it is imperative to address the annulus defects and reinstate the structural integrity of the annulus29,30. The majority of animal experiments revealed that suturing the annulus fibrosus is shown to have a beneficial impact in preventing nucleus pulposus leakage, preserving disc height and spinal stability, delaying disc degeneration, and promoting healing of the annulus fibrosus6,31,32. In 2013, Bailey et al. published a two-year multicenter, single-blind, randomized controlled trial involving 750 patients who underwent discectomy33. The findings indicated that the use of annulus fibrosus suture was not associated with an elevated risk of complications, and may decrease the likelihood of recurrence and reoperation for early postoperative disc herniation. Zhao et al. demonstrated that the addition of annulus fibrosus repair to percutaneous transforaminal endoscopic discectomy resulted in superior clinical outcomes and reduced the likelihood of surgical segment recurrence and intervertebral instability in young and middle-aged patients34. Our findings indicated that the combination of AUSS and bone-anchoring annulus suture technique proved to be efficacious in addressing annular defects located at the periphery of the vertebral body. This further highlighted the benefits of annulus suture techniques. Interestingly, the Pfirrmann grade did not show significant changes between pre- and postoperatively in our study. The primary objective of the annular suture technique was to restore the structural integrity of the annulus fibrosus and prevent reherniation, rather than directly reversing or halting pre-existing disc degeneration. Therefore, we speculate that the biochemical changes in the intervertebral discs during our follow-up period were slight, potentially insufficient to detect significant degenerative progression or improvement using MRI. Future studies with longer follow-up periods will be needed.

In this study, we employed an individualized suturing approach tailored to patient-specific situations, such as the type, size, shape, and location of the annular defect, as well as the quality of the surrounding annular tissue. For instance, when the defect is parallel to the endplate, the parallel suturing technique is typically chosen. In cases of crater-like defects, an X-shaped or triangular-shaped suture is often preferred, as these configurations better accommodate irregular defect shapes. Furthermore, adjustments in the anchor points within the annulus fibrosus are required based on the quality of the annular tissue surrounding the defect. If the superficial annular layers at the puncture site are too thin or fragile, suturing may fail due to the suture cutting. We emphasize that these methods are not rigid but should be flexibly tailored to individual patient conditions to achieve optimal annular closure.

One significant advantage of the Smile suture device is its ability to fix an anchor on the vertebral bone because of its unique design and craftsmanship3. However, the clinical application of the Smile suture device remains limited, which indeed restricts the widespread adoption of this technique. It is worth noting that when the initial bone or annular anchoring attempt fails, the surgeon should select an alternative anchor point on the vertebral body or normal annulus tissue to suture. In clinical practice, the quality of the bone or annulus fibrosus may be too poor to suture in some patients. Moreover, if nerve irritation by stitches is evident, suturing should be abandoned. For these patients, we recommend extending postoperative bed rest to facilitate scar formation of the annulus fibrosus.

This study had some limitations. Firstly, due to the study’s retrospective nature and small sample size combined with the short follow-up period of one year, our study was prone to selection biases. Secondly, this study was designed as a case series to primarily assess the feasibility, safety, and preliminary efficacy of the novel bone-anchoring annular suture technique. In the future, we plan to conduct a prospective study to compare the long-term clinical and radiological outcomes of the bone-anchoring annular suture technique and nucleus pulposus excision without annular suturing. The expected follow-up period is 3 years. Patients will be assessed postoperatively at 3 days and 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for this future study will be consistent with those of our current study.

Conclusion

In this study, three new types of bone-anchoring annulus suture techniques were introduced to fully close the annulus fibrosus defects at the edge of the vertebral body. The results indicated that the combination of the AUSS technique and the bone-anchoring annulus suture technique yielded a satisfactory clinical outcome, with no instances of recurrence observed throughout the follow-up period. In summary, our study provided critical insights and a practical framework for addressing annular defects near the vertebral body edge.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- VAS:

-

Visual analog scale

- ODI:

-

Oswestry disability index

- UBE:

-

Unilateral biportal endoscopy

- JOA:

-

Japanese Orthopaedic Association

- LDH:

-

Lumbar intervertebral disc herniation

- AUSS:

-

Arthroscopic-assisted uni-portal spinal surgery

- UNSES:

-

Uni-portal non-coaxial spinal endoscopic surgery

References

Kotheeranurak, V. et al. Full-endoscopic lumbar discectomy approach selection: a systematic review and proposed algorithm. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 48 (8), 534–544 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Research trends of percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy in the treatment of lumbar disc herniation over the past decade: a bibliometric analysis. J. Pain Res. 16, 3391–3404 (2023).

Ren, C., Qin, R., Li, Y. & Wang, P. Microendoscopic discectomy combined with annular suture versus percutaneous transforaminal endoscopic discectomy for lumbar disc herniation: a prospective observational study. Pain Physician. 23 (6), E713–E21 (2020).

Guardado, A. A., Baker, A., Weightman, A., Hoyland, J. A. & Cooper, G. Lumbar intervertebral disc herniation: annular closure devices and key design requirements. Bioengineering (Basel) 9 (2) (2022).

Yang, C-H. et al. The effect of annular repair on the failure strength of the porcine lumbar disc after needle puncture and punch injury. Eur. Spine J. 25 (3), 906–912 (2016).

Bateman, A. H. et al. Closure of the annulus fibrosus of the intervertebral disc using a novel suture application device-in vivo porcine and ex vivo biomechanical evaluation. Spine J. 16 (7), 889–895 (2016).

Miller, L. E., McGirt, M. J., Garfin, S. R. & Bono, C. M. Association of annular defect width after lumbar discectomy with risk of symptom recurrence and reoperation: systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 43 (5), E308–E315 (2018).

Shriver, M. F. et al. Lumbar microdiscectomy complication rates: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg. Focus. 39 (4), E6 (2015).

Moliterno, J. A. et al. Results and risk factors for recurrence following single-level tubular lumbar microdiscectomy. J. Neurosurg. Spine 12 (6), 680–686 (2010).

Carragee, E. J., Han, M. Y., Suen, P. W. & Kim, D. Clinical outcomes after lumbar discectomy for sciatica: the effects of fragment type and anular competence. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 85 (1), 102–108 (2003).

McGirt, M. J. et al. A prospective cohort study of close interval computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging after primary lumbar discectomy: factors associated with recurrent disc herniation and disc height loss. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 34 (19), 2044–2051 (2009).

Wang, Y. et al. Annulus fibrosus repair for lumbar disc herniation: a meta-analysis of clinical outcomes from controlled studies. Global Spine J. 14 (1), 306–321 (2024).

Li, Z-Z., Cao, Z., Zhao, H-L., Shang, W-L. & Hou, S-X. A pilot study of full-endoscopic annulus fibrosus suture following lumbar discectomy: technique notes and one-year follow-up. Pain Physician 23 (5), E497–E506 (2020).

Xi, J. et al. Analysis of the clinical efficacy of visualization of percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy combined with annulus fibrosus suture in lumbar disc herniation. Neurosurg. Rev. 47 (1), 54 (2024).

Peng, Y-X., Zhang, Y., Yang, Y., Wang, F. & Yu, B. Clinical effect of full endoscopic lumbar annulus fibrosus suture. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 19 (1), 261 (2024).

Cui, H-X., Wang, Y., Liu, Y-H. & Guo, M-L. Clinical study of microendoscopic discectomy + fibrous ring suture versus microendoscopic discectomy alone in the treatment of lumbar disc herniation in young and middle-aged patients. Pak J. Med. Sci. 40 (4), 690–694 (2024).

Hu, Z. et al. A suture technique for ruptured annulus fibrosus following decompression under percutaneous transforaminal endoscopic discectomy. J. Vis. Exp. 203 (2024).

Zhu, C. et al. [Early effectiveness of unilateral biportal endoscopic discectomy combined with annulus fibrosus suture in the treatment of lumbar disc herniation]. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi 36 (10), 1186–1191 (2022).

Qi, L. et al. The clinical application of jetting suture technique in annular repair under microendoscopic discectomy: a prospective single-cohort observational study. Med. (Baltim). 95 (31), e4503 (2016).

Jiang, L., Jing, X., Qiu, X. & Hu, Q. A novel repair strategy using knotless squeeze anchors for lumbar disc herniation with endplate junction lesions under biportal endoscopic spinal surgery. Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 166 (1), 171 (2024).

Mancini, M. R., Horinek, J. L., Phillips, C. J. & Denard, P. J. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a review of surgical techniques and outcomes. Clin. Sports Med. 42 (1), 81–94 (2023).

Wang, F., Wang, R., Zhang, C., Song, E. & Li, F. Clinical effects of arthroscopic-assisted uni-portal spinal surgery and unilateral bi-portal endoscopy on unilateral laminotomy for bilateral decompression in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis: a retrospective cohort study. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 19 (1), 167 (2024).

Choy, W. J., Phan, K., Diwan, A. D., Ong, C. S. & Mobbs, R. J. Annular closure device for disc herniation: meta-analysis of clinical outcome and complications. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 19 (1), 290 (2018).

Thomé, C. et al. Effectiveness of an annular closure device to prevent recurrent lumbar disc herniation: a secondary analysis with 5 years of follow-up. JAMA Netw. Open 4 (12), e2136809 (2021).

Kienzler, J. C. et al. Three-year results from a randomized trial of lumbar discectomy with annulus fibrosus occlusion in patients at high risk for reherniation. Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 161 (7), 1389–1396 (2019).

Sanginov, A., Krutko, A., Leonova, O. & Peleganchuk, A. Bone resorption around the annular closure device during a postoperative follow-up of 8 years. Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 166 (1), 40 (2024).

Martens, F., Lesage, G., Muir, J. M. & Stieber, J. R. Implantation of a bone-anchored annular closure device in conjunction with tubular minimally invasive discectomy for lumbar disc herniation: a retrospective study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 19 (1), 269 (2018).

Kienzler, J. C. et al. Incidence and clinical impact of vertebral endplate changes after limited lumbar microdiscectomy and implantation of a bone-anchored annular closure device. BMC Surg. 21 (1), 19 (2021).

Ahlgren, B. D., Lui, W., Herkowitz, H. N., Panjabi, M. M. & Guiboux, J. P. Effect of anular repair on the healing strength of the intervertebral disc: a sheep model. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 25 (17), 2165–2170 (2000).

Chiang, C-J. et al. The effect of a new anular repair after discectomy in intervertebral disc degeneration: an experimental study using a porcine spine model. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 36 (10), 761–769 (2011).

Rickers, K., Bendtsen, M., Le, D. Q. S. & Veen AJd, Bünger, C. E. Biomechanical evaluation of annulus fibrosus repair with scaffold and soft anchors in an ex vivo porcine model. SICOT J. 4, 38 (2018).

Heuer, F., Ulrich, S., Claes, L. & Wilke, H-J. Biomechanical evaluation of conventional anulus fibrosus closure methods required for nucleus replacement. Laboratory investigation. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 9 (3), 307–313 (2008).

Bailey, A., Araghi, A., Blumenthal, S. & Huffmon, G. V. Prospective, multicenter, randomized, controlled study of anular repair in lumbar discectomy: two-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 38 (14), 1161–1169 (2013).

Zhao, Y-F., Tian, B-W., Ma, Q-S. & Zhang, M. Study on the clinical effect of percutaneous transforaminal endoscopic discectomy combined with annulus fibrosus repair in the treatment of single-segment lumbar disc herniation in young and middle-aged patients. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 40 (3 Part-II), 427–432 (2024).

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi (2024JC-YBMS-702), the Key Research and Development Program of Shaanxi (2024SF-YBXM-382), the Yunnan Revitalization Talent Support Program, and Yunnan health training project of high level talents (H-2024084).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: En Song and Fengtao Li; Methodology: Fang Wang and Jie Li; Writing - original draft preparation: Jizheng Li and Kening Sun; Writing - review and editing: Bo Zhang and Dong Wang. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was performed according to the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University. All patients have signed written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, F., Li, J., Li, J. et al. Bone anchoring annular suture technique for repairing annular defects at vertebral body edge following lumbar discectomy. Sci Rep 15, 5047 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89179-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89179-7