Abstract

The safety and impact of embryo vitrification as a more reliable approach for cryopreservation in assisted reproductive techniques (ARTs) on the nervous system is uncertain. This study was aimed to investigate the expression level of imprinting genes in the hippocampus of offspring derived from vitrified embryo transfer. The hippocampus of the 2-day-old offspring from three experimental groups included vitrification (blastocysts derived from vitrified embryos), sham (the embryos at the blastocyst stage obtained through in vitro fertilization (IVF)) and control was removed for molecular, histological and behavioral analysis. There was no statistically noteworthy difference in survival, cleavage and blastocysts rate between vitrification and sham groups. Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, 3b and Igf2 upregulated in the vitrified group compared to the sham and control groups. The gene expression level of Meg3 declined dramatically and the intensity of DNA methylation in CpG island of Meg3 significantly elevated in the vitrification group. A notable disparity was observed in the quantity of dark neurons in the hippocampus of the offspring, spatial learning and memory abilities between the control and vitrification groups. According to these results, embryo vitrification may alters gene expression in brain hippocampus tissue and disturbs genomic imprinting, dark neuron formation and spatial memory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Assisted reproductive techniques (ARTs) are being considered as potent effective therapeutic approach for infertile couples who endure mental, economic and social burden1,2. Vitrification as an important technique for embryo cryopreservation is increasingly and consistently used in ART clinics worldwide, without precise consideration of the benefits and harms3,4,5,6. In some countries such as the United States of America, indication of vitrification has doubled since 20156,7. However, the safety of this nature-opposing procedure is still unclear. Scientists have speculated epigenetic dysregulation may be responsible for the increased likelihood of negative outcomes in the offspring conceived through ART. Therefore, discovering any alterations in the epigenetic pattern of embryos who undergo vitification would be of great value.

Embryo vitrification decreases the pluripotency of mouse blastocysts and the methylation level of promoter region of genes contributed to differentiation8. It also disturbs the methylation status of the whole genome9. Several research groups have found the embryo vitrification alters expression level of imprinted genes in the fetus and placenta10,11. It has been shown that vitrification increases the methylation level and gene imprinting related disorders5. The regulation of epigenetic imprinting is associated with DNA methyltransferase (Dnmts) family. Dnmts family consists of Dnmt1, Dnmt2, Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b and Dnmt3l which are conserved in mammals12. Among these genes, Dnmt1 plays a crucial role in preserving DNA methylation, whereas Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b are important for initiating DNA methylation during murine oogenesis and early embryo development13,14.

Epigenetic imprinting genes impact the brain development and emotional behaviors15. Several imprinted genes have been identified that are playing a key role in the brain development and function including Insulin-like growth factor (Igf2), H19, Maternally expressed gene 3 (Meg3) and Small ribonucleoprotein polypeptide N (Snrpn)16,17. Furthermore, the methylation levels of multiple imprinting genes in blood samples have been found to be associated with hippocampal volumes and hyperintensities. For instance, H19/Igf2 methylation and Snrpn methylation had a negative association with hippocampal volume and hippocampal grey matter hyperintensities, respectively18.

The H19 and Igf2 genes are situated on human chromosome 11 and mouse chromosome 7, with transcription occurring exclusively from the maternal and paternal alleles, respectively19. These two genes are two key fetal growth regulators with an opposite activity. H19 is a long noncoding RNA involved in the growth suppression, while Igf2 is an important growth factor in many developmental pathways20. The imprinted H19/Igf2 cluster is dysregulated in Silver-Russell Syndrome (SRS) and Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome (BWS) which are growth-affecting congenital imprinting disorders21. It has been reported that ARTs may increase the risk of BWS and SRS which are associated with epigenetic alterations in the H19/Igf2 cluster22,23,24. In rodents, Igf2 plays a vital role in memory and cognition25. For example the hippocampal Igf2 regulates learning and is necessary for long-term memory formation in mice26 and H19 participates in the process of neuronal apoptosis and activation of glial cells in the hippocampus of rodent27,28,29. Snrpn as an imprinting gene is highly expressed in adult brain and heart. It is associated with various neurodevelopmental disorders such as Angelman, Prader-Willi syndrome and autism spectrum disorders30,31,32. Snrpn encodes RNA-binding survival motor neuron (SMN) protein involved in the pre-mRNA splicing33,34. Meg3 is an imprinting gene located in human chromosome 14 and mouse chromosome 12. It encodes a long non-coding RNA that is highly expressed in the brain and plays roles in cell differentiation, postembryonic brain function, and axonal guidance35,36. It has been documented that overexpression of Meg3 leads to elevated levels of inflammatory mediators like tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in neurological diseases. Therefore, it is assumed that Meg3 contributes to neuroinflammation37. Downregulation of Meg3 was observed in various types of brain tumors such as neuroblastoma and wilms’ tumor38,39,40. Moreover, the loss of Meg3 has been reported in mouse blastocysts post in vitro fertilization (IVF) and vitrification procedures. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis revealed that the vitrification enhanced Meg3 methylation in human placenta41. In contrast, several research groups reported no significant differences in the methylation level of Meg 3 in human cord blood and placenta42,43,44,45. The review of literature indicates no data about the effects of vitrification on methylation patterns and expression levels of imprinting genes in the brain hippocampus of mouse offspring.

The hippocampus is an integral component of the limbic system, with a crucial function in the processes of learning, memory as well as cognitive and emotional actions46,47,48. A number of studies have indicated impairment of memory and learning following the hippocampal lesions which can occur due to various damaging factors and form dark neurons (DNs)49,50,51. Research has indicated that vitrification is a contributing factor in the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)52,53.

Therefore, considering the effect of ARTs on epigenetic regulation and the importance of the nervous system, we investigated the changes in the expression level of Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, Dnm3b, H19, Igf2, Snrpn and Meg3 as well as the methylation pattern of Meg3 in the brain hippocampus tissue of mouse offspring derived from frozen embryos. Additionally, DNs in hippocampus tissue, serving as an apoptosis marker, was evaluated by Cresyl violet staining. Moreover, the spatial learning and memory capabilities of the offspring were evaluated using Morris Water Maze (MWM) test.

Results

In both the vitrification and sham groups, the embryos at the blastocyst stage were transferred (15 per oviduct) into the oviducts of 10 pseudopregnant mice. Afterwards, the hippocampus of the 2-day-old offspring was removed for molecular and histological analysis. The MWM behavioral test was performed in one month-old BDF2 mice.

Vitrification had no effect on the cleavage, and embryo development

A total of 533 and 600 oocytes were used for the sham and vitrification groups, respectively. Table 1 indicates the embryo development rate between vitrification and sham groups. The survival rate for the vitrification groups was 99.13%. There was hardly any change in cleavage and blastocysts rates between experimental groups. Figure S1 shows the development of embryos in the sham (A, B) and the vitrification groups (C, D) in both cleavage and blastocyst stages.

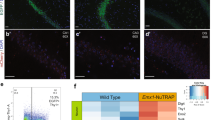

Vitrification changed the expression levels of dnmts and imprinting genes in hippocampal cells

The gene expression levels of Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b, Meg3, Snrpn, H19, and Igf2 in the hippocampus were quantitatively evaluated using qRT-PCR (Fig. 1). The gene expression analysis showed that Igf2, Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b upregulated significantly in the hippocampus of offspring derived from the frozen embryo transfer (3.09 ± 0.3, 1.5 ± 0.02, 2.7 ± 0.4 and 1.5 ± 0.04, respectively) compared to the sham (1.22 ± 0.4, 1.1 ± 0.06, 1.3 ± 0.2 and 1.04 ± 0.05, respectively) and control groups (p-value < 0.001). On the other hand, the Meg3 expression level declined dramatically in the sham and vitrification groups (0.17 ± 0.04 ,0.11 ± 0.07; respectively) compared to the control group (p-value < 0.001). Regarding Snrpn (vitrification: 0.8 ± 0.17, sham: 0.59 ± 0.2) and H19 (vitrification: 1.6 ± 0.5, sham: 1.04 ± 0.3), the study groups did not show any substantial variances (p-value > 0.05).

The expression level of imprinting genes in the studied groups. The expression level of Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b, and Igf2 increased in the vitrification groups. The expression levels of H19 and Snrpn remained unchanged among the groups. Meg3 exhibited a decline in both sham and vitrification groups in comparison to the control group (p < 0.05).

Vitrification enhanced the DNA methylation level of Meg3

We performed MSP to assess DNA methylation in the CpG islands of the Meg3 gene. The result clearly indicates the higher intensity of methylation level in the vitrification group in comparison to the control and sham groups (Fig. S2).

Vitrification had a notable influence on the quantity of DNs in the hippocampus

The histological evaluation showed that DNs existed in various regions of the hippocampus in all groups (Fig. 2A). The mean number of DNs was 5 ± 0.4 ,8 ± 0.55, and 15 ± 0.88 in the hippocampus of the control, sham and vitrification groups, respectively (Fig. 2B). The number of DNs increased significantly in the vitrification group in comparison to the control one (p-value < 0.05).

Vitrification decreased spatial learning and memory

The MWM test was utilized to evaluate spatial learning and memory (Fig. S3). The mean swimming velocity (12.1 ± 1.3, 11.9 ± 1.8, 12.4 ± 0.9 for control, sham, and vitrification groups, respectively) during training days revealed no significant differences among the groups, indicating that swimming speed had no effect on the animal’s performance (Fig. 3A). Based on the repeated measures statistical analysis, the learning process of animals in all study groups improved over 3 consecutive days. Figure 3B illustrates that the control group exhibited significantly superior learning outcomes compared to both the sham and vitrification groups. The mean escape latency in the group control was substantially shorter than in the vitrification and sham groups, according to the Tukey’s Post-hoc test (Vitrification: 59.84 ± 0.89, 57.91 ± 1.7, 49.9 ± 2.7 s (s) for day1, day 2, and day 3, respectively. Sham: 58.85 ± 0.91, 55.05 ± 1.42, 46.829 ± 3.1s forday1, day 2, and day 3, respectively. Control: 55.39 ± 0.85, 53.59 ± 1.66, 36.656 ± 2.57s for day1, day 2, and day 3, respectively).

The Morris water maze behavioral test results. (A) Mean swimming velocity. (B) Spatial learning of the experimental groups in the MWM test. The mean scape latency to find the hidden platform, *p < 0.05 compared with control group. (C) The travel distance to reach the hidden platform, *p < 0.05 compared with control group. (D) The time spent in the target quadrant. *p < 0.05 compared with control group. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 10).

The distance traveled by the animals in different experimental groups to find the concealed platform in the maze showed a statistically significant difference among the groups. As can be seen in the Fig. 3C, animals in the control group traveled less distance while no notable difference was observed in the traveled-distance between the vitrification and sham groups (vitrification: 696.9 ± 51.75, 654.8 ± 56.58, 571.1 ± 42.97 cm for day1, day 2, and day 3, respectively. Sham: 683.2 ± 65.12, 588.8 ± 57.65, 528.8 ± 71.86 cm for day1, day 2, and day 3, respectively. Control: 597.9 ± 39.01, 558.1 ± 37.11, 335.8 ± 44.27 cm for day1, day 2, and day 3, respectively). The special memory and the time spent in the platform area during the probe test of the MWM are indicated in Fig. 3D. Regarding the time allocated in the platform area and its vicinity, the results indicated a substantial difference between the vitrification and the control groups (12.14 ± 0.9 and 20.22 ± 1.23 s, respectively, p-value < 0.05), whereas no significant difference was found between the vitrification and the sham groups (12.14 ± 0.9 and 14.5 ± 1.02 s, respectively, p-value < 0.05).

Discussion

Vitrification stands as a vital technique develops for the cryopreservation of embryos in ART clinics54. Embryo cryopreservation indications are for preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD), avoidance of OHSS (ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome) and patient’s or physician’s preference55. Unfortunately, vitrification has been shown to have adverse effects on the methylation status of imprinting genes5. This raises a key question of whether vitrification impacts the long-term health outcomes of the offspring and if it can be optimized as a technology. Herein, we evaluated the effects of vitrification on the expression levels of Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b, Meg3, Snrpn, H19, and Igf2 genes, as well as the methylation level of the Meg3, the number of DNs in hippocampal brain tissue and spatial learning and memory abilities in the offspring.

The results related to embryo preimplantation development showed that vitrification had no effect on the cleavage and embryo development. The majority of previous studies showed that the development of frozen and fresh embryos was similar which is in agreement with our findings41,56,57. In contrast, Movahed et al. showed that blastocysts formation rate remarkably decreased following vitrification/thawing at the 2-cell stage embryos11. The discrepancy between our results and this study may be probably related to the different mouse species, vitrification method and technician expertise. According to most studies, it is concluded that the main reason behind the widespread use of vitrification is improved embryo survival and live birth rates.

Epigenetic reprogramming is crucial in embryonic development, and alterations in imprinted gene regulation can impact their functionality. The molecular mechanisms of imprinting genes revealed that the DNA methylation is the most important and the main epigenetic mechanism that differentiates the paternal or maternal imprinting genes that should be inherited to the next generation. Aberrant DNA methylation may result in the abnormal development of embryos and have a negative effect on their offspring1,2,10. DNA methyltransferases such as Dnmt1, Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b play a pivotal role in the early embryo development through modulation of epigenetic methylation status13,14. Additionally, they play a role in the formation of memories and behavioral plasticity58. Literature has reported that Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b are expressed in postnatal developing brain59,60,61. In this study, we found that Dnmt1, Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b upregulated in the hippocampus of 2-day-old offspring derived from vitrified two-cell embryos while Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b expression levels were decreased in vitrified oocytes and the blastocysts derived from vitrified oocytes of various mammal species4,62,63,64,65. Moreover, the expression level of Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b genes were declined in mouse blastocysts from IVF and vitrification at the two-cell stage compared to the blastocysts from in vivo fertilization66. Accordingly, it seems that the effect of vitrification on the expression pattern of Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b changes during different developmental stages.

We further evaluated the expression of Snrpn, H19, Igf2, and Meg3 imprinting genes in the hippocampus of 2-day-old offspring which are related to memory and cognition abilities. Our results indicated different expression patterns of these imprinting genes that may be associated with the methylation at different sites within the imprint regions that cover different transcription factor binding sites67. Several studies evaluated the effects of IVF and vitrification on the expression of imprinting genes in embryos and fetuses, reporting contradictory results in different mammals. Li et al. indicated that the aberrant expression of H19, along with normal expression of Igf2 was observed in IVF-derived mouse embryos68. X.-M. Zhao et al. demonstrated that H19 was downregulated in bovine blastocysts derived from vitrified two-cell embryos compared to fresh ones69. Likewise, Jahangiri et al. disclosed that H19 expression was decreased while Igf2 expression was increased in mouse blastocysts from vitrified and fresh two-cell embryos compared to in vivo blastocysts. They reported no significant difference between fresh IVF-derived blastocysts and vitrified ones70,71. Haq et al. exhibited that there were no significant differences in H19 and Igf2 expression between fresh and post-vitrification murine blastocysts72. However, in porcine, it has been shown that Igf2 expression declined in vitrified blastocysts compared to non-vitrified ones73. Movahedin et al. revealed that there was no significant difference in the expression of H19 and Igf2 between human vitrified blastocysts and non-vitrified ones74. Regarding Snrpn expression, vitrification did not change its expression in bovine blastocysts75.

In the context of long-term effects of IVF, Le et al. investigated the effect of IVF on the expression of H19 and Igf2 in the liver and skeletal muscle tissues of IVF-derived mice from birth to the age of 1.5 years. They implied that Igf2 was upregulated and H19 downregulated in both the liver and skeletal muscle of IVF mice at birth and three weeks of age. However, no differences were found in the expression of H19 and Igf2 at ten weeks of age. Both H19 and Igf2 were upregulated in the liver of 1.5 years-old mice, whereas, H19 was downregulated and Igf2 was upregulated in skeletal muscle of the IVF group. They also showed that the expression levels of H19, and Igf2 may be associated with their methylation status76. Their results showed that IVF caused alterations in the expression pattern of the H19 and Igf2 during postnatal periods. It should be noted that all above mentioned studies did not evaluate the expression level of imprinting genes in the brain of vitrified embryos. There is a study that reported altered expression of imprinting genes in the brain tissue of in vitro maturation (IVM) offspring77.

Our assessment also showed that vitrification enhanced the DNA methylation level of Meg3, resulting in downregulation of Meg3 in hippocampal cells. Probably, the increase in DNA methylation level of Meg3 is associated with higher expression of Dnmt1, Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b. According to the literature, the expression of Meg3 is of great importance in postembryonic brain function78. Some studies reported that vitrification enhanced Meg3 methylation in human placenta and chorionic villi samples41,79. In contrast, a number of studies have found no significant differences in the methylation of Meg 3 in human cord blood43,44. The reason for the difference in results is due to the heterogeneity in the sample source and the methodology of vitrification, which has led to the contradictions in the results of these studies.

DN is a neuronal degeneration characterized by the presence of contracted, intensely stained neurons49,50,51. We observed a notable increase in the quantity of DNs in the vitrification group in comparison to the control group. DN formation occurs due to various damaging factors. Some deleterious factors cause the formation of DNs through the production of free radicals. Studies have shown that one of these factors is vitrification, which causes the formation of ROS52,53. Since the hippocampus is vulnerable to oxidative stress, free radicals formation due to vitrification can lead to the production of DNs by arresting cell function80,81. It is possible that the decrease in the expression of Meg3 in the hippocampus of newborns born from frozen embryo transfer may lead to the formation of DNs through increased ROS production and apoptosis.

The hippocampus, being a component of the limbic system, has a central role in memory, learning, cognitive functions and emotional actions82,83. Hence, we assessed the spatial learning and memory of 2 day-old mice in all three experimental groups using the MWM test. The results indicated that the spatial learning ability was impaired in the both sham and vitrification groups compared to the control group. In consistent with our result, Ecker et al. illustrated in vitro culture of mouse embryos impaired the spatial learning and memory abilities84. However, some murine studies have noticed that offspring derived from IVF and embryo vitrification show spatial learning and memory abilities similar to the offspring derived from in vivo fertilization85,86,87. Since learning and memory abilities are age-dependent, these different results may be due to the age difference among the mice88. Furthermore, the use of different mouse species and sample sizes are other possible causes of contradiction in these results. Besides, in this study, the result of the MWM test may correlate with the result of the Meg3 expression. Rat studies revealed that Meg3 downregulated in cognitive disorders including Alzheimer’s disease, diabetic cognitive impairments, isoflurane-induced cognitive dysfunction and postoperative cognitive dysfunction. These studies also implied that Meg3 upregulation improved spatial learning, and memory abilities, suppressed inflammatory response, and reduced apoptosis of hippocampal neurons89,90,91,92.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that embryo vitrification alters brain hippocampus tissue gene expression and disturbs genomic imprinting, DNs formation and spatial learning and memory abilities. Since studies on the risk of childhood health after ART show conflicting results, it is imperative to conduct additional research to comprehensively evaluate the safety of vitrification on the mental and behavioral changes of offspring to elucidate these conflicting results and the underlying mechanisms.

Methods

The female and male B6D2F1 (C57BL/6×DBA/2) mice utilized in this research were acquired from the Royan Institute. (Tehran, Iran). All experimental protocols were conducted in accordance with the animal care guideline set by The Research and Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (IR.SUM.REC1399.499). This study is also reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines. All substances and chemical reagents utilized in the current investigation, unless stated otherwise, were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Study design

Three experimental groups were designed as follows:

-

Vitrification group: the mouse embryos obtained through IVF were vitrified when they reached the two-cell stage. After thawing, the embryos were developed to the blastocyst stage under controlled conditions of 37 °C and 5% CO2, and then transferred into the oviducts of ten pseudopregnant mice. Six out of ten pseudopregnant mice became pregnant which resulted in live birth. 43 offspring were born in the vitrification group.

-

Sham group: mouse embryos derived from IVF at the blastocyst stage were transferred to the oviducts of pseudopregnant mice. Seven out of ten pseudopregnant mice became pregnant which resulted in live birth. 47 offspring were born in the sham group.

-

Control: mouse embryos derived from natural mating of female and male BDF1 mice aged between 6 and 8 weeks old. Ten pregnant mice were followed until offspring birth in the control group and 80 offspring were born after 21 days.

Soon after birth, the hippocampus of the 2-day-old offspring were removed for molecular (n = 10 per group) and histological (n = 6 per group) analysis. The spatial learning and memory assessment were carried out in one month-old male mice (n = 10 per group).

For the vitrification and sham groups, six pups (hippocampus) from six different mothers (one per mother) were used for histological examination and ten pups from five different mothers (two per mother) were used for molecular examination. For the control group, six pups from six mothers (one per mother) were randomly used for histological examination. One offspring each from the newborns of ten mothers were randomly used for molecular assessment.

The remainder of the offspring were kept until 28 days to evaluate spatial learning and memory with the MWM test. For the vitrification and sham groups, two offspring from each of five mothers were randomly used for the MWM test. For the control group, one offspring each from the newborns of ten mothers were randomly used for the MWM test.

In vitro fertilization

Ovarian superovulation was induced in six to eight week-old female BDF1 mice (n = 20) with intra peritoneal injection of pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG, 10 IU) (Gonaser, Laboratories Hipra, Spain), followed with 10 IU Human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) (PDpreg: Pooyeshrarou Co, Iran) injection after a 48-hour interval. Fourteen hours post HCG injection, mice that had undergone superovulation were euthanized by cervical dislocation, and cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs) were collected from the ampulla of the oviduct. Simultaneously, caudal epididymal sperm were collected from BDF1 male mice aged 10–12 weeks and introduced into a droplet drops of human tubal fluid medium (HTF) supplemented with bovine serum albumin (BSA, 4 mg/ml). The sperm suspension underwent capacitation after being incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 45 min. Afterward, an appropriate amount of sperm (1 × 106 sperm/ml) was inseminated into the drop of HTF medium containing COCs for 6 hours. Next, fertilized oocytes were rinsed in flushing holding medium (FHM) and cultured in potassium simplex optimized medium (KSOM) supplemented with 0.4% BSA, essential and non-essential amino acid (EAA, NEAA) for a duration of 24 h at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2. The embryos at the two-cell stage were separated into two distinct groups: vitrification and sham. The embryos of the vitrification group were frozen while the embryos of the sham group were incubated for a period of 72 h until they reached the blastocyst stage. The embryo developmental rate was ultimately evaluated post fertilization to calculate the rate of cleavage and blastocyst development in the sham group.

Embryo vitrification and thawing

The vitrification of embryos was performed at the 2-cell stage by the Vitrification KIT (Kitazato Biopharmaceuticals, Shizuoka, Japan). After equilibrating of 2-cell embryos in the Equilibration Solutions (ES, comprising of 7.5% Ethylene glycol, and 7.5% DMSO) for a duration of 5 min at room temperature, the embryos were placed in Vitrification Solution (VS, comprising 15% Ethylene glycol, 15% DMSO, and 0.5 M sucrose) for 30 s then immediately loaded onto a cryotop and immersed in liquid nitrogen. In order to thaw the vitrified embryos, the cryotop was dipped into pre-warmed (37 °C) Thawing (TS, containing 0.5 M sucrose), Diluent (DS, containing 0.25 M sucrose), and Washing solution (WS, containing 0.1 M sucrose) for 1, 3 and, 5 min, respectively. The recovered embryos were cultured in KSOM medium supplemented with 4 mg/ml BSA, EAA, and NEAA up to the blastocyst formation in an incubator under conditions of 37 °C temperature with 5% CO2. The Survival, cleavage, and blastocyst rates were calculated in the vitrification group.

Procedure of embryo transfer

Six to eight weeks-old CD1 female mice (n = 10 per group) were used as recipients for the embryos. To synchronize their estrous cycles prior to mating, CD1 female mice were in group housing (4 to 10 females per cage) for 10–14 days. We added only two females that were in estrus cycle into each vasectomized CD1 male cage. The next morning female mice were examined to determine if a vaginal plug was present (Fig. S4A). Those with a positive vaginal plug were considered pseudopregnant. 2.5 days pseudopregnant mice were anesthetized with an injection of ketamine (the concentration is 0.01 ml/g of a 10 mg/ml solution) and xylazine (0.005 ml/g of a 2 mg/ml solution) intraperitoneally. Both ovaries were exposed by an incision (measuring 0.5 to 1 cm) on the caudal dorsal area’s skin and body wall. Once the ampulla was identified under the stereomicroscope, the embryos at the blastocysts stage (n = 15 per oviduct) were transferred into the oviducts (Fig. S4B, C). After capillary insertion, the oviduct was placed back into the abdominal cavity. The body wall and skin were closed using polyglycolic acid and nylon, 6 –0 suture line. Following birth, the 2-day-old offspring was euthanized by decapitation with sharp scissors and the hippocampus was removed (Fig. S4 D–F).

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis and quantitative RT-PCR analysis

The synthesize of complementary DNA via reverse transcription was performed following the procedure outlined in our earlier research93. Briefly, we extracted total RNA from brain tissues using a Single Cell to cDNA Kit (Hasti Noavaran Gene Royan, Tehran, Iran) according to the instructions and cDNA was synthesized simultaneously.

Reverse transcription followed by qRT-PCR to evaluate the imprinting genes expression level using the StepOne™ Real-Time PCR instrument (Applied Biosystems, USA). Technical and biological replicates were considered double and triple, respectively. Table 2 contains the sequences of the primers utilized for qRT-PCR. The mixture of qRT-PCR reaction included specific primers, synthesized cDNA, distilled water, ROX dye, and SYBR Green q-PCR master mix (Yekta Tajhiz Azma, Tehran, Iran). The real-time PCR protocol consisted of three steps: a 3-min hot-start at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5s (denaturation), 60 °C for 15s (amplification), and 72 °C for 10s (extension). Beta2-microglobulin (B2m) was utilized as a reference gene for RT-PCR data normalization. The Livak method (2-ΔΔCT formula) was employed to calculate relative gene expression.

Extracting genomic DNA and bisulfite treatment

Genomic DNA was obtained from hippocampus utilizing DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The purity and quantity of extracted DNA were assess using the NanoDrop 1000 (Thermo Scientific, US) through 260/ 280 nm absorbance measures in which an absorbance ratio of ~ 1.8 was accepted as purified dsDNA. The extracted DNA samples were subsequently used for bisulfite modification using EZ DNA Methylation Lightning™ Kit (Zymo Research, Orange, CA) in accordance with the instructions provided by the manufacturer.

Methylation specific polymerase chain reaction (MSP)

Conventional MSP was utilized to determine the methylation status at the promoter region of Meg3, employing methylation specific primers (Table 3). The first-round PCR reaction contained HotStarTaq Master Mix (1×), 2 µM of outer primers (mMeg3p-Forward and mMeg3p-Reversed) and 10 ng bisulfite-modified DNA and H2O. The first-round of Meg3 DNA amplification was as follows: 10 min at 95 °C, then 40 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 35 s and 72 °C for 40 s; and a final extension step of 12 min at 72 °C. The second-round of amplification was prepared in the following order: HotStarTaq Master Mix (1×), 2 µM of inner primers (mMeg3-Unmethylated-Forward and mMeg3p-Reversed/ mMeg3-Methylated-Forward and mMeg3p-Reversed), 1 µl of template DNA from the first round of amplification, and H2O. Times and temperatures for denaturation, annealing, and polymerization were similar to the first-round PCR. The 2% agarose gel electrophoresis with UV illumination was used to analyze the PCR products under UV illumination. For each sample, MSP results were recorded as methylated and unmethylated maternal allele of Meg3 band (A 210 bp) on the agarose gel. This experiment was repeated three times to ensure the reproducibility and accuracy of data. We performed this experiment on three pups from three different mothers (one per mother) which were randomly selected in each group.

Tissue sampling, cresyl violet staining, quantification of DNs

Two day-old mice from each study group (n = 6 per group) were sacrificed. The brains were extracted accurately and washed with sterile normal saline (Fig. S4E). Subsequently, the brain tissues underwent fixation in 10% neutral formalin, dehydrated using a range of ethanol concentrations, clarified with xylene, and then encased in paraffin. The blocks of samples were then sliced into coronal serial sections that were 5 μm thick, stained with cresyl violet, and the images were taken under a light microscope (Olympus BX51; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The hippocampal DNs were quantified using the stereological technique. A following formula was applied to determine the average number of DNs per given area47,48.

The formula consists of three key components: “ΣQ” which signifies the total number of particles appearing in sections, “a/f” representing the area per grid frame, and “ΣP” denoting the total sum of grid frames.

The Morris water maze (MWM) behavioral test

The MWM behavioral test was employed to assess spatial learning and memory in one-month-old male BDF2 mice (n = 10 per group). During the experiment, the animals were submerged in a water pool and had to remember the position of the platform concealed just beneath the water’ surface of the water using the spatial and visual cues located outside the maze. The apparatus was a black round pool with 140 cm, 70 cm and 25 cm of diameter, height and depth respectively, which was filled with water at temperature of 20 °C. The maze had four equivalent quarters and there was a concealed round platform in the center of the northeast quarter. The maze was equipped with visual signals such as a door, a computer, a window, and posters, which were positioned in various areas around the maze. The experimenter, the computer, and the guide shapes outside the maze remained consistent throughout the duration of the experiment.

The animals’ movements and behaviors were automatically monitored and documented through the utilization of the Noldus EthoVision software (v13) (Noldus Company, Netherlands). Additionally, a charged coupled device (CCD) camera was positioned overhead at the center of the maze for data collection.

The training program involved instructional sessions over three days. During the learning phase, the mice were taught for three continuous days to discover the hidden platform placed in the middle of the northeast quadrant, which was roughly 1.5 cm below the water level. Every session consisted of four trials with four distinct starting points. Throughout every trial, the animal was given a 90-second to find the concealed platform. Following each trial, the mice were permitted to remain on the platform for 20 s before the next trial commenced. At the end of each day’s training session, the animal was taken out of the pool, dried with a towel, and placed back into its cage.

The invisible platform was replaced during the retention testing (probe trial) on the fourth day. At this stage, the mice were evaluated in a 60-second test and the time spent in the quarter of the target circle where the platform had previously been situated was calculated over days 1–3 of training. During this test, we measured several parameters such as traveled-distance, discovery time of the concealed platform, number of entries into the designated area and duration spent in the specific quadrant during the spatial probe evaluation.

Statistical analysis

Statistical data was analyzed using unpaired Student’s t-test between two groups and One-way ANOVA test with repeated measures as well as Tukey’s test among three groups using SPSS software (version 22) to a confidence level of p-value < 0.05. Molecular results were analyzed using REST 2009 software (Qiagen).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Jiang, Z. et al. Genetic and epigenetic risks of assisted reproduction. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 44, 90–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2017.07.004 (2017).

Cannarella, R. et al. DNA methylation in offspring conceived after assisted Reproductive techniques: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 11, 859. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11175056 (2022).

Cobo, A. et al. Outcomes of vitrified early cleavage-stage and blastocyst-stage embryos in a cryopreservation program: evaluation of 3,150 warming cycles. Fertil. Steril. 98, 1138–1146 e1131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.07.1107 (2012).

Zhao, X. M. et al. Effect of vitrification on promoter CpG island methylation patterns and expression levels of DNA methyltransferase 1o, histone acetyltransferase 1, and deacetylase 1 in metaphase II mouse oocytes. Fertil. Steril. 100, 256–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.03.009 (2013).

Ma, Y. et al. Changes in DNA methylation and imprinting disorders in E9.5 mouse fetuses and placentas derived from vitrified eight-cell embryos. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 86, 404–415. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrd.23118 (2019).

Sargisian, N. et al. Cancer in children born after frozen-thawed embryo transfer: a cohort study. PLoS Med. 19, e1004078. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004078 (2022).

De Geyter, C. et al. 20 years of the European IVF-monitoring Consortium registry: what have we learned? A comparison with registries from two other regions. Hum. Reprod. 35, 2832–2849. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deaa250 (2020).

Zhu, W. et al. Effect of embryo vitrification on the expression of brain tissue proteins in mouse offspring. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 36, 973–977. https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590.2020.1734785 (2020).

Derakhshan-Horeh, M. et al. Vitrification at Day3 stage appears not to affect the methylation status of H19/IGF2 differentially methylated region of in vitro produced human blastocysts. Cryobiology 73, 168–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cryobiol.2016.08.003 (2016).

Berntsen, S. et al. The health of children conceived by ART: ‘the chicken or the egg?‘. Hum. Reprod. Update. 25, 137–158. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmz001 (2019).

Movahed, E., Shabani, R., Hosseini, S., Shahidi, S. & Salehi, M. Interfering effects of in Vitro fertilization and vitrification on expression of Gtl2 and Dlk1 in mouse blastocysts. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 14, 110–115. https://doi.org/10.22074/ijfs.2020.5984 (2020).

Del Falconi, C., Torres-Arciga, V. M., Matus-Ortega, K., Diaz-Chavez, G., Herrera, L. A. & J. & DNA methyltransferases: from evolution to clinical applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 8994. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23168994 (2022).

Uysal, F., Cinar, O. & Can, A. Knockdown of Dnmt1 and Dnmt3a gene expression disrupts preimplantation embryo development through global DNA methylation. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 38, 3135–3144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-021-02316-9 (2021).

Uysal, F., Ozturk, S. & Akkoyunlu, G. DNMT1, DNMT3A and DNMT3B proteins are differently expressed in mouse oocytes and early embryos. J. Mol. Histol. 48, 417–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10735-017-9739-y (2017).

Ho-Shing, O. & Dulac, C. Influences of genomic imprinting on brain function and behavior. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 25, 66–76 (2019).

Zhang, H., Tao, J., Zhang, S. & Lv, X. LncRNA MEG3 reduces hippocampal Neuron apoptosis via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in a rat model of temporal lobe Epilepsy. Neuropsychiatr Dis. Treat. 16, 2519–2528. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S270614 (2020).

Wilkinson, L. S., Davies, W. & Isles, A. R. Genomic imprinting effects on brain development and function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 832–843. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2235 (2007).

Lorgen-Ritchie, M. et al. Imprinting methylation predicts hippocampal volumes and hyperintensities and the change with age in later life. Sci. Rep. 11, 943. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-78062-2 (2021).

Nordin, M., Bergman, D., Halje, M., Engstrom, W. & Ward, A. Epigenetic regulation of the Igf2/H19 gene cluster. Cell. Prolif. 47, 189–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpr.12106 (2014).

Chang, S. Developmental Role of H19 and IGF2 in Mouse and Human (University of Pennsylvania, 2021).

Nativio, R. et al. Disruption of genomic neighbourhood at the imprinted IGF2-H19 locus in Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome and silver–Russell syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 1363–1374 (2011).

Gicquel, C. et al. In vitro fertilization may increase the risk of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome related to the abnormal imprinting of the KCNQ1OT gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72, 1338–1341 (2003).

DeBaun, M. R., Niemitz, E. L. & Feinberg, A. P. Association of in vitro fertilization with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and epigenetic alterations of LIT1 and H19. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72, 156–160. https://doi.org/10.1086/346031 (2003).

Cocchi, G. et al. Silver–Russell syndrome due to paternal H19/IGF2 hypomethylation in a twin girl born after in vitro fertilization. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part. A 161, 2652–2655 (2013).

Alberini, C. M. IGF2 in memory, neurodevelopmental disorders, and neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Neurosci. 46, 488–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2023.03.007 (2023).

Pandey, K. et al. Neuronal activity drives IGF2 expression from pericytes to form long-term memory. Neuron 111, 3819–3836 e3818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2023.08.030 (2023).

Han, C. L. et al. Long non-coding RNA H19 contributes to apoptosis of hippocampal neurons by inhibiting let-7b in a rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Cell. Death Dis. 9, 617. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-018-0496-y (2018).

Han, C. L. et al. LncRNA H19 contributes to hippocampal glial cell activation via JAK/STAT signaling in a rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J. Neuroinflammation 15, 103. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-018-1139-z (2018).

Feng, C. et al. Methionine restriction improves cognitive ability by alleviating hippocampal neuronal apoptosis through H19 in Middle-aged insulin-resistant mice. Nutrients 14, 4503 (2022).

Nicholls, R. D. & Knepper, J. L. Genome organization, function, and imprinting in Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2, 153–175. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.genom.2.1.153 (2001).

Horn, D. A. et al. Expression of the tissue specific splicing protein SmN in neuronal cell lines and in regions of the brain with different splicing capacities. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 16, 13–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-328x(92)90188-h (1992).

Marshall, C. R. et al. Structural variation of chromosomes in autism spectrum disorder. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 82, 477–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.12.009 (2008).

Glenn, C. C. et al. Gene structure, DNA methylation, and imprinted expression of the human SNRPN gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 58, 335–346 (1996).

Leff, S. E. et al. Maternal imprinting of the mouse snrpn gene and conserved linkage homology with the human prader-Willi syndrome region. Nat. Genet. 2, 259–264. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng1292-259 (1992).

da Rocha, S. T., Edwards, C. A., Ito, M., Ogata, T. & Ferguson-Smith, A. C. Genomic imprinting at the mammalian Dlk1-Dio3 domain. Trends Genet. 24, 306–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2008.03.011 (2008).

Zhou, Y., Zhang, X. & Klibanski, A. MEG3 noncoding RNA: a tumor suppressor. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 48, R45–53. https://doi.org/10.1530/JME-12-0008 (2012).

Dong, J., Xia, R., Zhang, Z. & Xu, C. lncRNA MEG3 aggravated neuropathic pain and astrocyte overaction through mediating miR-130a-5p/CXCL12/CXCR4 axis. Aging (Albany NY) 13, 23004–23019. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.203592 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. Maternally expressed gene 3, an imprinted noncoding RNA gene, is associated with meningioma pathogenesis and progression. Cancer Res. 70, 2350–2358. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3885 (2010).

Ye, M. et al. Downregulation of MEG3 promotes neuroblastoma development through FOXO1-mediated autophagy and mTOR-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 16, 3050–3061. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.48126 (2020).

Armario, A., Lopez-Calderon, A., Jolin, T. & Castellanos, J. M. Sensitivity of anterior pituitary hormones to graded levels of psychological stress. Life Sci. 39, 471–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-3205(86)90527-8 (1986).

Hiura, H. et al. Genome-wide microRNA expression profiling in placentae from frozen-thawed blastocyst transfer. Clin. Epigenetics 9, 79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-017-0379-6 (2017).

Mani, S., Ghosh, J., Coutifaris, C., Sapienza, C. & Mainigi, M. Epigenetic changes and assisted reproductive technologies. Epigenetics 15, 12–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/15592294.2019.1646572 (2020).

Choufani, S. et al. Impact of assisted reproduction, infertility, sex and paternal factors on the placental DNA methylome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 28, 372–385. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddy321 (2019).

Litzky, J. F. et al. Placental imprinting variation associated with assisted reproductive technologies and subfertility. Epigenetics 12, 653–661. https://doi.org/10.1080/15592294.2017.1336589 (2017).

Camprubi, C. et al. Stability of genomic imprinting and gestational-age dynamic methylation in complicated pregnancies conceived following assisted reproductive technologies. Biol. Reprod. 89, 50. https://doi.org/10.1095/biolreprod.113.108456 (2013).

Rastegar-Moghaddam, S. H. et al. Grape seed extract effects on hippocampal neurogenesis, synaptogenesis and dark neurons production in old mice. Can this extract improve learning and memory in aged animals? Nutr. Neurosci. 25, 1962–1972. https://doi.org/10.1080/1028415X.2021.1918983 (2022).

Ibla, J. C., Hayashi, H., Bajic, D. & Soriano, S. G. Prolonged exposure to ketamine increases brain derived neurotrophic factor levels in developing rat brains. Curr. Drug Saf. 4, 11–16. https://doi.org/10.2174/157488609787354495 (2009).

Buzsaki, G. & Moser, E. I. Memory, navigation and theta rhythm in the hippocampal-entorhinal system. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 130–138. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3304 (2013).

Bagheri-Abassi, F., Alavi, H., Mohammadipour, A., Motejaded, F. & Ebrahimzadeh-Bideskan, A. The effect of silver nanoparticles on apoptosis and dark neuron production in rat hippocampus. Iran. J. Basic. Med. Sci. 18, 644–648 (2015).

Krysko, D. V., Berghe, V., D’Herde, T., Vandenabeele, P. & K. & Apoptosis and necrosis: detection, discrimination and phagocytosis. Methods 44, 205–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.12.001 (2008).

Zsombok, A., Toth, Z. & Gallyas, F. Basophilia, acidophilia and argyrophilia of dark (compacted) neurons during their formation, recovery or death in an otherwise undamaged environment. J. Neurosci. Methods 142, 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.08.005 (2005).

Gupta, M. K., Uhm, S. J. & Lee, H. T. Effect of vitrification and beta-mercaptoethanol on reactive oxygen species activity and in vitro development of oocytes vitrified before or after in vitro fertilization. Fertil. Steril. 93, 2602–2607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.01.043 (2010).

Ahn, H. J. et al. Characteristics of the cell membrane fluidity, actin fibers, and mitochondrial dysfunctions of frozen-thawed two-cell mouse embryos. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 61, 466–476. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrd.10040 (2002).

Chen, H., Zhang, L., Meng, L., Liang, L. & Zhang, C. Advantages of vitrification preservation in assisted reproduction and potential influences on imprinted genes. Clin. Epigenetics 14, 141. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-022-01355-y (2022).

Bosch, E. et al. Circulating progesterone levels and ongoing pregnancy rates in controlled ovarian stimulation cycles for in vitro fertilization: analysis of over 4000 cycles. Hum. Reprod. 25, 2092–2100. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deq125 (2010).

Bosch, E., De Vos, M. & Humaidan, P. The future of cryopreservation in assisted Reproductive technologies. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 11, 67. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2020.00067 (2020).

Nagy, Z. P., Shapiro, D. & Chang, C. C. Vitrification of the human embryo: a more efficient and safer in vitro fertilization treatment. Fertil. Steril. 113, 241–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.12.009 (2020).

Morris, M. J. & Monteggia, L. M. Role of DNA methylation and the DNA methyltransferases in learning and memory. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 16, 359–371. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2014.16.3/mmorris (2014).

Wu, H. et al. Dnmt3a-dependent nonpromoter DNA methylation facilitates transcription of neurogenic genes. Science 329, 444–448. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1190485 (2010).

Simmons, R. K., Howard, J. L., Simpson, D. N., Akil, H. & Clinton, S. M. DNA methylation in the developing hippocampus and amygdala of anxiety-prone versus risk-taking rats. Dev. Neurosci. 34, 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1159/000336641 (2012).

Liu, N. et al. Neuroprotective mechanisms of DNA methyltransferase in a mouse hippocampal neuronal cell line after hypoxic preconditioning. Neural Regen. Res. 15, 2362–2368. https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.285003 (2020).

Cheng, K. R. et al. Effect of oocyte vitrification on deoxyribonucleic acid methylation of H19, Peg3, and Snrpn differentially methylated regions in mouse blastocysts. Fertil. Steril. 102, 1183–1190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.06.037 (2014).

Ma, Y. et al. WGBS combined with RNA-seq analysis revealed that Dnmt1 affects the methylation modification and gene expression changes during mouse oocyte vitrification. Theriogenology 177, 11–21 (2022).

Stinshoff, H., Wilkening, S., Hanstedt, A., Brüning, K. & Wrenzycki, C. Cryopreservation affects the quality of in vitro produced bovine embryos at the molecular level. Theriogenology 76, 1433–1441 (2011).

Vendrell-Flotats, M. et al. In vitro maturation with leukemia inhibitory factor prior to the vitrification of bovine oocytes improves their embryo developmental potential and gene expression in oocytes and embryos. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 7067 (2020).

Movahed, E., Soleimani, M., Hosseini, S., Akbari Sene, A. & Salehi, M. Aberrant expression of miR-29a/29b and methylation level of mouse embryos after in vitro fertilization and vitrification at two‐cell stage. J. Cell. Physiol. 234, 18942–18950 (2019).

Murrell, A. et al. An intragenic methylated region in the imprinted Igf2 gene augments transcription. EMBO Rep. 2, 1101–1106. https://doi.org/10.1093/embo-reports/kve248 (2001).

Li, T. et al. IVF results in de novo DNA methylation and histone methylation at an Igf2-H19 imprinting epigenetic switch. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 11, 631–640. https://doi.org/10.1093/molehr/gah230 (2005).

Zhao, X. M. et al. Effect of 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine on methylation of the putative imprinted control region of H19 during the in vitro development of vitrified bovine two-cell embryos. Fertil. Steril. 98, 222–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.04.014 (2012).

Jahangiri, M., Shahhoseini, M. & Movaghar, B. H19 and MEST gene expression and histone modification in blastocysts cultured from vitrified and fresh two-cell mouse embryos. Reprod. Biomed. Online 29, 559–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.07.006 (2014).

Jahangiri, M., Shahhoseini, M. & Movaghar, B. The Effect of Vitrification on expression and histone marks of Igf2 and Oct4 in blastocysts cultured from two-cell mouse embryos. Cell. J. 19, 607–613. https://doi.org/10.22074/cellj.2018.3959 (2018).

Haq, N. M. D. et al. Potential ability for implantation of mouse embryo post-vitrification based on Igf2, H19 and Bax Gene expression. Italian J. Anat. Embryol. 124, 409–421 (2019).

Bartolac, L. K., Lowe, J. L., Koustas, G., Grupen, C. G. & Sjoblom, C. Vitrification, not cryoprotectant exposure, alters the expression of developmentally important genes in in vitro produced porcine blastocysts. Cryobiology 80, 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cryobiol.2017.12.001 (2018).

Movahedin, M., Daneshvar, M., Salehi, M. & Noruzinia, M. P-180 alterations of methylation level of H19/IGF2 DMR differentially methylated region(DMR) in human blastocysts following re-vitrification. Hum. Reprod. 37 https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deac107.173 (2022).

Yodrug, T., Parnpai, R., Hirao, Y. & Somfai, T. The effects of vitrification after equilibration in different concentrations of cryoprotectants on the survival and quality of bovine blastocysts. Anim. Sci. J. 91, e13451. https://doi.org/10.1111/asj.13451 (2020).

Le, F. et al. In vitro fertilization alters growth and expression of Igf2/H19 and their epigenetic mechanisms in the liver and skeletal muscle of newborn and elder mice. Biol. Reprod. 88, 75. https://doi.org/10.1095/biolreprod.112.106070 (2013).

Wang, N. et al. Altered expressions and DNA methylation of imprinted genes in chromosome 7 in brain of mouse offspring conceived from in vitro maturation. Reprod. Toxicol. 34, 420–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2012.04.012 (2012).

Gordon, F. E. et al. Increased expression of angiogenic genes in the brains of mouse meg3-null embryos. Endocrinology 151, 2443–2452. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2009-1151 (2010).

Dimitriadou, E. et al. Abnormal DLK1/MEG3 imprinting correlates with decreased HERV-K methylation after assisted reproduction and preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Stress 16, 689–697. https://doi.org/10.3109/10253890.2013.817554 (2013).

de Oliveira, L. et al. Different sub-anesthetic doses of ketamine increase oxidative stress in the brain of rats. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 33, 1003–1008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.05.010 (2009).

Ng, F., Berk, M., Dean, O. & Bush, A. I. Oxidative stress in psychiatric disorders: evidence base and therapeutic implications. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 11, 851–876. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1461145707008401 (2008).

Kim, S. M. & Frank, L. M. Hippocampal lesions impair rapid learning of a continuous spatial alternation task. PLoS One 4, e5494. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0005494 (2009).

Pouzet, B. et al. The effects of NMDA-induced retrohippocampal lesions on performance of four spatial memory tasks known to be sensitive to hippocampal damage in the rat. Eur. J. Neurosci. 11, 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00413.x (1999).

Ecker, D. J. et al. Long-term effects of culture of preimplantation mouse embryos on behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 101, 1595–1600. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0306846101 (2004).

Li, L. et al. Normal epigenetic inheritance in mice conceived by in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 12, 796–804. https://doi.org/10.1631/jzus.B1000411 (2011).

Wang, Z. Does embryo vitrification affect the mice offsprings’ growth, development and the nervous system? Fertil. Steril. 110, e232–e233 (2018).

Wang, Z. Y. & Chen, S. Z. S. C. Comparison of the effects of vitrification and slow freezing on the growth and development of offspring using a mouse model (2020).

Wu, W. W., Oh, M. M. & Disterhoft, J. F. Age-related biophysical alterations of hippocampal pyramidal neurons: implications for learning and memory. Ageing Res. Rev. 1, 181–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1568-1637(01)00009-5 (2002).

Yi, J. et al. Upregulation of the lncRNA MEG3 improves cognitive impairment, alleviates neuronal damage, and inhibits activation of astrocytes in hippocampus tissues in Alzheimer’s disease through inactivating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. J. Cell. Biochem. 120, 18053–18065 (2019).

Wang, Z. et al. LncRNA MEG3 alleviates diabetic cognitive impairments by reducing mitochondrial-derived apoptosis through promotion of FUNDC1-related mitophagy via Rac1-ROS axis. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 12, 2280–2307 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Long non-coding RNA maternally expressed 3 (MEG3) regulates isoflurane-induced cognitive dysfunction by targeting miR-7-5p. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 32, 453–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/15376516.2022.2042881 (2022).

Ye, L. et al. Long non-coding RNA MEG3 alleviates postoperative cognitive dysfunction by suppressing inflammatory response and oxidative stress via has-miR-106a-5p/SIRT3. Neuroreport 34, 357–367. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNR.0000000000001901 (2023).

Dehghani-Mohammadabadi, M. et al. Melatonin modulates the expression of BCL-xl and improve the development of vitrified embryos obtained by IVF in mice. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 31, 453–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-014-0172-9 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Samaneh Hosseini for her help in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.H. and S.H. performed the research and acquired the data. H.A. and M.S. designed the research, analyzed and interpreted the data. All authors were involved in drafting and revising the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

All procedures were approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (IR.SUM.REC1399.499).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hosseini, S., Hosseini, S., Aligholi, H. et al. Embryo vitrification impacts learning and spatial memory by altering the imprinting genes expression level in the mouse offspring’ hippocampus. Sci Rep 15, 5419 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89857-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89857-6