Abstract

The deep-sea human occupied vehicles (HOV) typically have the characteristics such as large dimensions, complex structures, and significant nonlinearities of their dynamic models, which makes it difficult for the operator to precisely control the vehicle for completing the tasks such as target tracking, grabbing, and specific area exploration. Establishing an accurate hydrodynamic model and obtaining an appropriate control algorithm are the key to solving the aforementioned problems. Therefore, this paper takes the 7000-meter deep-sea human occupied vehicle “Jiaolong” as the research object. The accurate hydrodynamic coefficients of the vehicle are obtained based on the maneuvering test data of the vehicle, and a complete six-degree-of-freedom model of the vehicle is established. The precision of the dynamic model is verified by the test data of Pacific deep submerging. The simulation studies of typical maneuvering conditions are conducted to demonstrate that the vehicle possesses good maneuverability. By utilizing the dynamic model, the control strategy for the HOV is derived using the control algorithm of adaptive integral sliding mode (AISMC). The simulations confirm that this control method can significantly enhance the control accuracy of the vehicle, and the challenges posed by model uncertainties of the model and external disturbances of the environment are effectively addressed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The deep-sea environment, especially at depths exceeding 4000 meters, holds vast natural resources and unknown marine species. With the advancement of underwater technology, human-occupied vehicles (HOVs) have become essential for exploring these regions. Countries such as China, the U.S., Russia, and Japan have developed various types of HOVs to accomplish deep-sea exploration, resource extraction, equipment maintenance, and rescue missions. Some representative HOV are listed in Table 11,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. However, HOVs’ large size and complex structures pose challenges in accurately modeling their dynamic behavior. The forces acting on HOVs exhibit strong nonlinearity, making maneuvering and control demanding. Therefore, precise dynamic models and appropriate control algorithms are essential to enhance the performance and success rate of deep-sea HOV missions.

The complex structure of the HOV leads to strong coupling between the hydrodynamic coefficients of the vehicle, which makes it difficult to establish an accurate dynamics model. Many scholars have conducted research on dynamic modeling of large underwater vehicles to address the above issue. In 1967, Gertler and Hagen first derived the six-degree-of-freedom motion equations for the submarine, and predicted the force acting on submarine during its motion9. Building upon this, Feldman revised the parameters of the motion equations to improve the prediction accuracy of external forces and torques10. Park further conducted an analysis of the maneuvering performance under high angle of attack sailing conditions based on the aforementioned model, and the accuracy of the dynamic model was verified through the experiment conducted in a towing tank11.Fossen established the motion equations of the underwater vehicles in vector form based on Newton-Euler and Lagrangian formulations. This model is used internationally due to its generality and suitability for theoretical analysis12. Liu et al. derived the six-degree-of-freedom motion equations of HOV, and the rotational motion characteristics under the influence of ocean currents was investigated13. Wei established a six-degree-of-freedom model for remotely operated underwater vehicles, and analyzed the forces and moments acting on the vehicle during motion. With the model, the numerical simulations of vertical movement, rotational motion and Z-shaped of HOV were analyzed14. Park and Kim established a six-degrees-of-freedom dynamic model of a semi-submersible underwater vehicle. The involved factors of model was further expanded by incorporating cable interference15. Kim16 and Li17 identified the hydrodynamic coefficients in the dynamic model of underwater vehicle based on numerical simulation method. By combining experimental data, the accuracy of dynamic model and the maneuverability of the vehicle were validated to be effectively improved. The current researches about dynamic modeling of underwater vehicles primarily focuses on Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs). The shape of AUVs are mainly in teardrop or flattened, which significantly differ from the complex structures of HOV and leads to the completely different parameters of the dynamic model. The enormous size of HOV makes it difficult to measure the parameters through the experiment of water tank, and the simulation estimation also face the problem of limited accuracy, which results in insufficient accuracy of subsequent control algorithms.

The trajectory tracking accuracy of HOV directly determines its performance of motion and operation, but the complex dynamic characteristics of HOV make it a persistent challenge to achieve suitable method of precise tracking. Traditional methods, such as PID control, have been widely used in early researches, and the control accuracy of PID has been widely certified18. However, Smallwood noted that PID controllers struggle to provide accurate tracking even in linear second-order systems, and they cannot dynamically compensate for uncertain vehicle dynamics or time-varying ocean disturbances19. To address these limitations, more advanced control techniques have been developed, including adaptive control20, backstepping21, neural network control22, fuzzy control23, model predictive control (MPC)24, and sliding mode control (SMC)25. SMC is particularly robust against unmodeled dynamics, parameter variations, and external disturbances, which makes it highly suitable for underwater robot trajectory tracking26. However, practical applications mainly focused on the object of AUV. In the process of controlling the HOV, the algorithm demand fast convergence to time-varying trajectories, which can lead to large control forces in SMC that risk thruster saturation, an undesirable outcome in real operations27. Integral sliding mode control (ISMC), which guarantees finite-time convergence while maintaining strong robustness against model uncertainties and external disturbances, offers a solution to this issue28. Through application process of ISMC in underwater trajectory tracking, the researchers find that ISMC does not fully eliminate tracking errors, but converge to a bounded range rather than to zero. Additionally, ISMC requires knowledge of the upper bounds of uncertainties and disturbances, which is often difficult to obtain in practical settings. Recently, the adaptive nonsingular terminal sliding mode control has provided a new approach for improving system performance and robustness in the presence of external disturbances. By designing a nonlinear sliding surface and using an adaptive barrier function to estimate unknown disturbance bounds, this method achieves finite-time convergence and enhances the system’s adaptability to disturbances29. Moreover, the dynamic behavior of coupled systems, such as unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) and unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs), has been explored, offering valuable insights into vehicle interactions and cable forces. This research has significantly improved the understanding of coupled systems’ dynamics in ocean environments, providing important references for autonomous underwater vehicle control30. On the other hand, perturbation observer-based robust control has proven effective in dealing with both matched and unmatched uncertainties in nonlinear systems. By applying multiple sliding surfaces, this method accurately estimates unknown disturbances and designs robust controllers that significantly enhance system performance31. For underactuated systems, fast terminal sliding mode control combining with disturbance observers provides a finite-time convergence solution, which has been experimentally validated as effective against nonlinearities and parametric uncertainties32. Furthermore, studies that integrate adaptive barrier functions with nonsingular sliding mode control have shown that fast stabilization is possible for perturbed nonlinear systems without prior knowledge of disturbance bounds, and the practicality of the control system is enhanced33.

Motivated by the aforementioned considerations, a novel approach called Adaptive Integral Sliding Mode Control (AISMC) has been proposed. The aim of this study is to establish an accurate six-degree-of-freedom dynamic model of a deep-sea Human Occupied Vehicle (HOV) and employing the AISMC strategy to enhance motion control performance under conditions of uncertainty. The proposed control approach seeks to address issues of model uncertainty, external disturbances, and control accuracy. The motivation behind this research is to improve the success rate of HOV operations in challenging underwater environments, ensuring higher precision and reliability of the control method. The achievement of this project can effectively improve the operational performance of HOVs and promote the development of deep-sea exploration technology.

The main contribution of this paper is three-fold as follows:

-

(1)

An accurate dynamic model of Jiaolong Deep-Sea Human Occupied Vehicles (HOV) is obtained and the hydrodynamic coefficients of the model are identified with real-world data.

-

(2)

For solving the trajectory tracking control problem of HOV with model uncertainties and unknown external disturbances, an Adaptive Integral Sliding Mode Control is proposed in this paper, which allows the controller design to operate without prior knowledge of the upper bounds of uncertainties and disturbances.

-

(3)

In many articles, the roll and pitch angles are often neglected due to the self-stability of the submersible, resulting in the use of four-degree-of-freedom motion equations. In contrast, we conducted a comprehensive six-degree-of-freedom motion simulation that accurately reflects the actual movement of the HOV.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section "Dynamic modeling of HOV in six degrees of freedom" introduces the six-degree-of-freedom dynamic modeling process of the HOVs. Section "Manipulation performance research of HOV" provides a detailed description of the simulation study results to validate the accuracy of the model with experimental data. Section "Trajectory tracking control for human occupied vehicles" proposes the trajectory tracking control algorithm of Adaptive Integral Sliding Mode Control (AISMC). Section "Discussion of results" discusses the parameter selection for AISMC and the trajectory tracking performance. Finally, Section "Conclusion" concludes the paper.

Dynamic modeling of HOV in six degrees of freedom

The dynamic model of an HOV is divided into two parts: the kinematic and dynamic models. These models form the foundation for simulating the vehicle’s maneuvering capabilities, which are then validated through experimental data.

Kinematic modeling

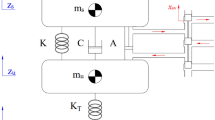

The kinematic model aims to define the transformation between the inertial coordinate system and the body-fixed coordinate system of the HOV. The body-fixed coordinate system originates at the vehicle’s center of mass, with the x-axis aligned along the vehicle’s longitudinal direction and the z-axis along its vertical direction. This relationship is depicted in Fig. 1. The transformation between these coordinate systems can be expressed by Eq. (1).

Here, the components \(\dot{X}\), \(\dot{Y}\) and \(\dot{Z}\) represent the velocity components of the vehicle along the X, Y, and Z axis in the inertial coordinate system, respectively. The \(\dot{\phi }\), \(\dot{\theta }\) and \(\dot{\psi }\) represent the angular velocity components of the vehicle along the X, Y, and Z axis in the inertial coordinate system, respectively. Similarly, u, v, w, p, q and r denote the velocity and angular velocity components along the axis of the body-fixed coordinate system of the vehicle. T and W can be obtained as:

Here, \(s(.)=sin(.)\), \(c(.)=cos(.)\), \(t(.)=tan(.)\).

Based on Eq. (1), the relationship between the body-fixed coordinate system and the inertial coordinate system is established. Various physical quantities can be transformed between these coordinate systems using this equation.

Dynamic modeling

The HOV can be considered as a rigid body while it moving in the deep-sea environment. Based on the six degrees of freedom rigid body motion and the principles of linear and angular momentum, the six degrees of freedom dynamic equations for the HOV can be derived as follows:

Here, \(x_G\), \(y_G\), \(z_G\) denote the three axis coordinates of the gravity center. \(I_xy\) denotes the moment of inertia on the XOY plane and so on. \(\sum _iF_{X_i}\) is the sum of external loads along the X-axis, and the \(\sum _iF_{K_i}\) is the sum of torque along the X-axis.

The external forces and moments acting on the HOV mainly include the thrust of the propeller, hydrodynamic forces, gravity, buoyancy, and some moments. After considering the effects of the aforementioned external loads and second-order hydrodynamic terms, the dynamic equation related to the degrees of freedom in longitudinal, lateral, and yaw modes can be transformed into the following forms:

The hydrodynamic model of the Jiaolong HOV is established by the equation set composed of Eqs. (10-15). Due to the complex shape of the HOV hull, the dynamic model of HOV exhibits highly nonlinear coupling characteristics, which makes the parameters of the model can not be calculated directly. The experiment for measuring the hydrodynamic parameters of the HOV were conducted in the towing tank at the China Ship Scientific Research Center, and the hydrodynamic parameters of the dynamic model were determined.

Manipulation performance research of HOV

This section evaluates the maneuvering performance of the HOV under various conditions, such as straight-line navigation, diving, and turning. The simulation results are compared with experimental data to validate the accuracy of the dynamic model.

Numerical simulation of HOV maneuvering performance

Straight-line motion

Based on the dynamic model of the HOV, the numerical simulations of the straight-line motion were conducted to observe the reaction of HOV under the thrust provided by the propeller. The thrust of the vessel was chosen as the one corresponded to the rated power of the propeller, which is 560N. The sailing depth is defined at the specified operational depth of the Jiaolong HOV, which is 6500m. Under the above conditions, the straight-line motion state of the Jiaolong HOV is shown in Fig. 2. With a thrust of 560N, the straight-line speed of the HOV stabilizes to 0.594 m/s. Due to the asymmetric shape of the HOV, a resultant force in Z-direction is generated during straight-line moving, which makes the vessel start to heel. After stabilization, the heel angle of HOV stabilizes at \(0.361^{\circ }\).

Heave motion

The heave motion along the Z-axis is one of the most important navigation mode for HOV. Therefore, the numerical simulation of HOV maneuvering performance along this degree of freedom was carried out. During the ascent process of the HOV, maintaining a velocity along the X-axis direction is usually necessary. The thrust of the propellers along the X-axis and Z-axis at rated power are 560N and 520N, and the initial velocities along the X-axis and Z-axis are 0.5m/s and 0m/s, respectively. The simulation results of the vehicle’s ascent motion under the above initial conditions are shown in Fig. 3. The speed of the HOV in the X-axis and Z-axis directions reach 0.676 m/s and 0.074 m/s while the ascent process stabilizes. The ratio of climbing speed to cruising speed reaches to 0.11, which proves that the HOV can perform a stable ascent motion with good performance. The descent process is similar to the ascent, which will not be elaborated here.

Rotary motion

Spiral motion is an important navigational maneuvers for the HOV to ascend or descend. Rotary motion is the foundation of the spiral motion, so it is necessary to conduct the research on maneuvering performance of rotary motion. A thrust of 438 N generated by the lateral propeller in rated power is introduced in the Y direction on the basis of the rated thrust of 560 N in the X direction, and the corresponding torque is 1241 Nm. The other initial conditions are the same as those of the heave motion. The simulation results of the vehicle’s rotary motion under are shown in Fig. 4. The turning radius of the HOV is 16.05 meters while no thrust along the Z-axis is applied to HOV. The X-axis speed, Y-axis speed and Z-axis speed were 0.524 m/s, 0.052 and 0.068 m/s, respectively, while the simulation process is stabilized. The generation of Z-axis velocity is due to the asymmetry in the hull structure of HOV, which makes the hull experience a vertical external force as depicted in Fig. 4(c) when rotating, and promotes the HOV to bow up and rise.

Spiral motion

By adding the thrust of Z-axis propeller on the basis of rotary motion simulation, the helical descent or ascent process of HOV can be reproduced, which is an important method for HOV to realize the stationary ascent and descent. The thrust generated by the vertical propeller is 500N under the rated power condition, with a corresponding torque of 571Nm, and the initial conditions are the same as those of the rotary motion. The numerical simulation results of spiral motion in space is plotted in Fig. 5. After adding vertical thrust, the vertical speed increased from 0.068 m/s to 0.08 m/s, and the X-axis cruising speed increased from 0.524 m/s to 0.6 m/s comparing with the rotary motion. The Z-axis velocity increased by 14% under the influence of vertical thrust which make HOV efficiently achieve spiral motion. The increase in the X-direction velocity resulted in the turning radius increasing of spiral motion, which is 20.1m as plotted in Fig. 6. The velocity of ascending generated during rotary motion is directly varied to opposite direction by applied the vertical thrust as plotted in Fig. 6(a), which achieves the autonomous control over the direction along Z-axis. The velocities and angular velocities in all directions remain within a certain range once the simulation process stabilizes, which demonstrates the capability of HOV to stably perform spiral descent or ascent maneuvers.

Experiment verification of HOV maneuvering performance

To validate the effectiveness of the HOV dynamic model, the comparisons between the numerical simulation and the data obtained by two times deep-diving experiments of the Jiaolong HOV are conducted.

Verification of diving conditions

For verify the dynamic model of Jiaolong HOV, the HOV diving test data from 7:32 AM on a specific day was selected to conduct comparison and validation. The comparison of numerical simulation and experiment are shown in Fig. 7. The experiment lasted for 2000 seconds and the depth of HOV decreases from 0m to 1320m. The Z-axis displacement obtained by numerical simulation and experiment exhibit a high degree of consistency, and the error is only 8m at the position of 1320m. Some discrepancy between the X-axis drag and velocity are existed before the HOV reaching the stable stage, with the experimental values exhibiting fluctuations?whereas the numerical simulation doesn’t. These differences may be caused by the manual adjustments by the submarine operator and detection errors from sensors. The Z-axis velocity and drag obtained by the two methods exhibit high consistency after the vehicle reaching the stable stage, with the biggest velocity error of 0.046m/s. It is evident that the dynamic model demonstrates high accuracy in simulating the descent process of the HOV.

Verification of straight-line navigation

Straight-line navigation is another typical operating state required for HOV during seabed operations. Therefore, the experiment data obtained by straight-line navigation were selected to validate the dynamic model. Manual control methods were used to manipulate the HOV during its navigation, and this control signal was directly converted into the thrust of the propeller in the simulation program. The comparison of navigation state obtained by experiment and numerical simulation is plotted in Fig. 8. The overall experiment lasted for 25 seconds. The displacement comparison results for the X, Y, and Z axes are shown in Figures 8(a), 8(b), and 8(c), respectively. The maximum positional deviation among the three axes is 1.6 meters in the Y-axis direction, while the minimum is 0.25 meters in the X-axis direction. The larger error in the Y-axis is due to a significant directional displacement of 12.15 meters, resulting in a relative error of 13.1%. The heading angles obtained by the two methods are stabilized around \(285^{\circ }\), with a maximum deviation of \(0.55^{\circ }\).

It can be seen that the dynamic model of the HOV accurately predicts the vehicle’s motion state during its descent and straight-line navigation, which can also effectively reflect the variations in the vehicle’s maneuvering performance.

Trajectory tracking control for human occupied vehicles

In above sections, we conducted a detailed simulation study on four typical maneuvers of manned submersibles: straight-line navigation, diving, turning, and spatial spiral, thoroughly analyzing their maneuverability characteristics. To further validate the maneuvering performance of the submersible under these motion patterns, this section will focus on the trajectory tracking control method. By implementing trajectory tracking control, we can more accurately assess the submersible’s response capabilities and control effects in different motion states, thereby providing empirical evidence for optimizing the submersible’s maneuvering system.

AISMC scheme design

Express the above kinematic and dynamic models in the following general form

where \(M\in R^{6\times 6}\)denotes the mass matrix,\(C\left( v \right) \in R^{6\times 6}\)denotes the Coriolis and centripetal forces matrix,\(D\left( v\right) \in R^{6\times 6}\)denotes the linear and quadratic damping matrix,\(G\left( \eta \right) \in R^6\)denotes the hydrostatic matrix; \(\tau =\tau _u+\tau _{dis}\), \(\tau _u\in R^6\)denotes the control input forces and moments,\(\tau _{dis}\in R^6\)denotes the lumped system uncertainty including model uncertain terms and external disturbances.

Assumption 1

\(J\left( \eta \right) \in R^{6\times 6}\) is the Jacobian matrix. To prevent the \(J\left( \eta \right)\) from becoming singular, the pitch angle \(\theta\) should be constrained to \(\left| \theta \right|<\theta _{\max }<\pi /2\). \(\theta _{\max }\) is the maximum pitch angle determined through experiments.

This assumption is quite reasonable, as the pitch angle of the HOV remains within \(\left| \pi /2 \right|\) during actual motion. Furthermore, due to the presence of restoring forces, it is unlikely for the HOV to enter the neighbourhood of \(\theta =\pm \pi /2\).

Assumption 2

The lumped system uncertainty is bounded

where \(\chi\) is an unknown constant.This assumption is generally valid because the system contains unknown parts, such as modeling inaccuracies and friction, which are bounded. Therefore, the state of the system is also bounded.

Assumption 3

The desired trajectory \(\eta _d\left( t \right) =\left[ x_d\left( t \right) ,y_d\left( t \right) ,z_d\left( t \right) ,\varphi _d\left( t \right) ,\theta _d\left( t \right) ,\psi _d\left( t \right) \right] ^T\) and its derivatives are smooth and bounded,satisfying that:\(0\leqslant \underline{{\eta }_d}\leqslant \parallel \eta _d(t)\parallel _{\infty }\le \bar{\eta }_d<\infty\),\(0\leqslant \dot{\underline{{\eta }_d}}\leqslant \parallel \dot{\eta }_d(t)\parallel _{\infty }\le \bar{\dot{\eta }}_d<\infty\),\(0\leqslant \ddot{\underline{{\eta }_d}}\leqslant \parallel \eta _d(t)\parallel _{\infty } \le \bar{\ddot{\eta }}_d<\infty\), where \(\underline{a}\) and \(\bar{a}\) indicating the upper and lower bounds and they are both positive normal numbers.

First,we define the position tracking errors as

where \(\eta _d\in R^6\) is a time-varying reference trajectory.

By differentiating Eq.(19) with respect to time and combing with system (16),we have

Taking v from Eq.(20) as the virtual control input, the desired velocity command can be obtained as

where \(K_1=\textrm{diag}\left( k_{11},\ldots \ldots ,k_{16} \right)\)is a positive definite matrix that need to be designed.

Based on the virtual control input, we define the velocity tracking errors as

Then,the integral sliding surface is defined as

where \(K_2=\textrm{diag}\left( k_{21},\ldots \ldots ,k_{26} \right)\) is the sliding surface parameter that need to be designed.

According to the design principle of sliding mode control, the proposed ISMC control law \(\tau _u\) consists of an equivalent term \(\tau _{u,eq}\) and a switching term \(\tau _{u,sw}\).In the absence of model uncertainties and external disturbances, the equivalent term alone can achieve the desired dynamics. The switching term is used to compensate for model uncertainties and disturbances caused by the external environment. These aggregated uncertainties are bounded, but their upper bounds are unknown. Therefore, an adaptive law is used to estimate the upper bounds and apply them to the switching term to eliminate these uncertainties. Thus, the equivalent term and the switching term are designed as follows:

where \(\varGamma =\left\| s \right\| \left\| M^{-1} \right\| \hat{\chi }\), \(\hat{\chi }\) is the estimated value of \(\chi\) and is updated through the following adaptive law as

Theorem 1

For systems (16) and (17), the control law Eq.(24)-(26) designed based on ISMC can make the velocity error converge to zero in finite time, and then the position error will also converge to zero in finite time.

Proof

Choose the following positive definite Lyapunov function as

where \(\tilde{\chi }=\hat{\chi }-\chi\)

By differentiating Eq.(27) with respect to time,we have

Substituting Eq.(18),Eq.(25) and Eq.(26) into the time derivative of V yields

where \(\sigma =\left\| M^{-1} \right\| \left( \chi -\left\| \tau _{dis} \right\| \right)\) \(>0\), When \(s \ne 0\), \(\dot{V} < 0\), indicating that \(V\) is bounded. The integral sliding surface \(s\) can converge to zero within a finite time. According to Theorem 1, the velocity error on the integral sliding surface will converge to zero within a finite time, and the position error will also converge to zero. Thus, the entire closed-loop system is stable. \(\square\)

Results

In this section, we demonstrate the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed Adaptive Integral Sliding Mode Control (AISMC) algorithm through trajectory tracking simulations. The four key motion modes-straight-line motion, heave motion, rotary motion, and spiral motion-are examined to assess the HOV’s dynamic performance. The dynamic model used in these simulations corresponds to the formulations described in Eqs. (16) and (17).The controller parameters are set as follows: \(K_1=\textrm{diag}\left( 10,10,10,10,10,10 \right)\), \(K_2=\textrm{diag}\left( 5,5,5,5,5,5 \right)\), \(l =5\). Detailed parameters for each motion type are provided in the following subsections. Figure 9 presents a schematic of the AISMC control scheme.

Straight-line motion

In this section,our current objective is to validate the straight-line motion of the submersible. By employing trajectory tracking control techniques, we seek to evaluate the submersible’s performance and control efficiency in adhering to linear trajectories. This validation process is pivotal in refining the submersible’s maneuvering system for straight-line motion scenarios.

The initial position and velocity are selected as

Figure 10 illustrates the position-time trajectory of a Human Occupied Vehicle (HOV) tracking a desired straight-line trajectory under integral sliding mode (ISMC) and adaptive integral sliding mode control (AISMC) strategies. The corresponding position and attitude tracking errors are shown in Fig. 11, while the linear and angular velocity tracking errors are presented in Fig. 12. These figures demonstrate that under both control strategies, the HOV can accurately track the desired trajectory, with errors stabilized within a bounded small neighborhood around the origin. Figures 11 and 12 further reveal that the adaptive integral sliding mode control strategy achieves convergence 5-10s faster than the integral sliding mode control strategy. Since the initial depth of the HOV and the desired trajectory’s depth are the same, \(z_e=0\). Figure 11(a) presents the tracking error of the HOV under both control strategies. Table 2 provides the convergence times and average tracking errors for each state under the three different strategies.

Figure 13 shows the control input for the HOV during trajectory tracking. Due to the asymmetry in the vertical direction, a vertical force is required to maintain the HOV at a constant depth while tracking a straight-line trajectory. The integral sliding mode control introduces chattering due to the sign function, whereas the adaptive integral sliding mode control reduces chattering by incorporating the adaptive law to compensate for concentrated uncertainties effectively.

Heave motion

In this section, we aim to validate the trajectory tracking performance of the submersible during heave motion. By focusing on heave motion trajectory tracking, we will assess the submersible’s responsiveness and control efficacy in maneuvering heave trajectories. This validation process is essential for enhancing the submersible’s maneuvering capabilities specifically in heave motion scenarios.

To validate the stability and robustness of the proposed controller,the initial states are selected as

Figure 14 illustrates the trajectory tracking of the HOV during diving and surfacing motions under both control strategies. The corresponding position and attitude tracking errors are shown in Fig. 15, and the linear and angular velocity tracking errors are presented in Fig. 16. Similar to the straight-line motion, the adaptive integral sliding mode control (AISMC) strategy demonstrates a faster convergence speed compared to the integral sliding mode control (ISMC) strategy. Figure 15a shows the tracking error of the HOV under both strategies, and Table 3 provides the convergence times and average tracking errors for each state under the two different strategies.

Figure 17 shows the control input during the trajectory tracking of the HOV during diving and surfacing motions. In Fig. 17b, since diving requires submersion, a thrust is needed in the pitch direction.Combining the thrust from other propellers enables the HOV to maintain a fixed pitch angle, allowing it to submerge along the desired straight line. Once it reaches the desired depth, it can proceed with its operations.

Rotary motion

In this section, our focus shifts to validating the trajectory tracking performance of the submersible during rotary motion. By delving into rotary motion trajectory tracking, Our aim is to assess the submersible’s trajectory tracking performance during rotary motion to optimize its control system, ensuring effectiveness and flexibility in rotary motion scenarios.

Selecting the initial position and velocity of the manned submersible as

Figure 18 shows the position-time trajectory of the Human Occupied Vehicle (HOV) tracking a spiral trajectory under integral sliding mode control (ISMC) and adaptive integral sliding mode control (AISMC) strategies. The corresponding position and attitude tracking errors are shown in Fig. 19, while the linear and angular velocity tracking errors are presented in Fig. 20. These figures demonstrate that under both control strategies, the HOV can accurately track the desired trajectory.From the position tracking error in Fig. 19a, it can be observed that the response speed of the HOV under the AISMC strategy is 5-10 seconds faster than under the ISMC strategy. Additionally, the steady-state error for ISMC is relatively larger. Table 4 provides the specific convergence times and average errors for both control strategies.

Figure 21b presents the control input during spiral trajectory tracking. As the HOV performs the spiral motion at a fixed depth, there is no need for roll and pitch maneuvers, resulting in zero torques in these directions, as shown in Fig. 21a. Similar to straight-line trajectory tracking, due to the asymmetry of the vehicle, a vertical force is required to maintain a constant depth.

Spiral motion

In this section, we will validate the maneuvering performance of the submersible under spiral motion using trajectory tracking control methods. By implementing trajectory tracking techniques, we can evaluate the submersible’s response and control effectiveness in navigating spiral trajectories. This validation process will contribute to optimizing the submersible’s maneuvering system in spiral motion scenarios.

The starting position and velocity of the human occupied vehicles are selected as

Figure 22a shows the trajectory tracking of the HOV’s spiral path under both control strategies, while Fig. 22b presents the horizontal projection of the spiral trajectory. It is evident that the HOV’s convergence speed under the AISMC strategy is faster than that under the ISMC strategy. The corresponding position and attitude tracking errors are shown in Fig. 23, and the linear and angular velocity tracking errors are presented in Fig. 24. These figures demonstrate that under both control strategies, the HOV can accurately track the desired trajectory, with errors stabilized within a bounded range.From Fig. 23a, it can be observed that the tracking error response speed of the HOV under the AISMC strategy is 5-15s faster than under the ISMC strategy. Table 5 provides the convergence times and average tracking errors for each state under both strategies. The results indicate that AISMC offers excellent robustness and rapid response.

Figure 25 shows the control inputs for the HOV during spiral trajectory tracking under both control strategies. Due to the spatial nature of the spiral motion, forces and torques are generated in all directions. The HOV needs to maintain a certain pitch angle for submersion as well as a specific roll angle. The HOV performs precise trajectory tracking with the aid of its thrusters. However, the switching term in ISMC contains a sign function, which induces chattering and thereby affects tracking accuracy.

Discussion of results

In this section, we present a detailed analysis of the simulation results for the dynamic performance and trajectory tracking of the Deep-Sea Human Occupied Vehicle (HOV) under various maneuvering conditions. The effectiveness of the proposed Adaptive Integral Sliding Mode Control (AISMC) is evaluated based on performance metrics such as convergence speed, tracking accuracy, and robustness against uncertainties and disturbances. The straight-line motion, heave motion, rotary motion, and spiral motion simulations demonstrate the capability of the proposed control strategy to achieve precise tracking of desired trajectories. Figures 10-25 provide detailed visual representations of the performance under both AISMC and Integral Sliding Mode Control (ISMC) strategies. The key observations from these simulations are as follows:

-

1.

Convergence Speed: The convergence time for each of the maneuvers was significantly reduced using AISMC compared to ISMC. For example, during the straight-line and spiral motions, the convergence times decreased by 10-12 seconds (Table 2 and Table 5). This is mainly due to the adaptive mechanism employed in AISMC, which allows for rapid compensation for system uncertainties and external disturbances. The faster response time enhances the efficiency of the HOV’s movement, which is critical for operations in dynamic underwater environments.

-

2.

Tracking Accuracy: The tracking errors for position, attitude, and velocity were substantially smaller with AISMC than with ISMC across all maneuvers. For instance, during the heave motion (Fig. 15), the tracking error averages were reduced by approximately 80%, indicating a marked improvement in accuracy. This higher precision is particularly crucial for tasks requiring detailed exploration or interaction with underwater objects, where even slight deviations could lead to mission failure or damage to equipment.

-

3.

Robustness to Uncertainties and Disturbances: One of the primary challenges in controlling deep-sea HOVs is dealing with the uncertainties in the dynamic model and external disturbances caused by factors such as ocean currents. The AISMC strategy demonstrated a significant advantage in maintaining robustness under these conditions. As shown in Fig. 20, the angular velocity tracking errors under AISMC were effectively minimized even in the presence of fluctuating disturbances. The adaptive law used in the controller successfully estimated and compensated for these uncertainties, which is evident from the smooth control input profiles (Fig. 21) without excessive chattering.

-

4.

Actuator Behavior: The control inputs generated under both strategies (Fig. 13 and 25) show that the AISMC method produced smoother actuator signals, which reduces the risk of actuator wear and potential system failures. In contrast, ISMC exhibited higher frequency chattering due to the use of the sign function in the switching term. This chattering effect not only reduces actuator lifespan but can also lead to inefficient power consumption. The adaptive mechanism in AISMC mitigates these issues, thereby improving the overall durability and reliability of the HOV.

-

5.

Maneuvering Performance: The rotary and spiral motions were specifically examined to assess the maneuvering capabilities of the HOV under complex motion patterns. The results indicate that AISMC allowed the HOV to achieve tighter turning radii and better stabilization during spiral trajectories compared to ISMC. This is particularly important for deep-sea exploration missions, where precision in maneuverability is required to navigate around obstacles or reach specific target points accurately. The ability to achieve a stable spiral descent, as demonstrated in Fig. 22, ensures that the HOV can maintain its planned trajectory even under changing environmental conditions.

-

6.

Experimental Validation Consistency: The results of the simulations were compared against experimental data obtained during deep-diving trials of the “Jiaolong” HOV. The comparisons (Figs. 7 and 8) showed a high degree of consistency between the experimental and simulated data, with minor discrepancies attributed to manual operator adjustments and sensor inaccuracies. The maximum positional deviation was within acceptable limits, demonstrating the reliability of the dynamic model and the control strategy in realistic scenarios.

Conclusion

In this article, an accurate Hydrodynamic model of the Jiaolong manned submersible is established, and the motion performance of the HOV was accurately simulated. Furthermore, the controller for autonomous control of the HOV is designed and the precise tracking of the target trajectory is achieved. The conclusions of this work are expressed as follows.

-

1.

Various hydrodynamic parameters of the HOV’s dynamic model were obtained based on the data from the experiment, and the precise dynamic model of the HOV is established. With the model, the vehicle trajectories of straight moving, turning, and spiral motion were simulated, and the simulation accuracy of the dynamic model was validated with experimental data which demonstrated model could accurately predict the motion performance of HOV.

-

2.

In this paper, we propose an adaptive integral sliding mode control (AISMC) method.The maneuverability of manned submersibles on straight-line navigation, heave motion, rotary motion, and spatial spiral motion were meticulously examined through simulation studies. The simulation results indicate that our control method improves the convergence speed by approximately \(10\%\) and enhances the tracking accuracy by around \(15\%\) comparing with the conventional ISMC. The empirical data obtained from these simulations and control implementations offer a robust foundation for optimizing the maneuvering system of deep-sea submersibles, ensuring better performance and reliability in real-world operations.

-

3.

First, due to the current limitations in access to deep-sea environments and the associated logistical challenges, it is currently not possible to conduct practical experimental validation on the HOV. In the future, this control algorithm can be applied to the HOV to verify its effectiveness. Second, research on path planning can be conducted based on the current control algorithm. After planning paths for complex deep-sea terrains, trajectory tracking control can be implemented based on the planned paths.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the China Ship Scientific Research Center, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data. They were used under license for the current study and are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from the China Ship Scientific Research Center. For data requests related to this study, please contact Dejun Li at lidj702@163.com.

References

Kohnen, W. Mts manned underwater vehicles 2017–2018 global industry overview. Mar. Technol. Soc. J. 52, 125–151 (2018).

Kohnen, W. Human exploration of the deep seas: Fifty years and the inspiration continues. Mar. Technol. Soc. J. 43, 42–62 (2009).

Sagalevitch, A. 25th anniversary of the deep manned submersibles mir-1 and mir-2. Oceanology 52, 817–830 (2012).

Sagalevich, A. M. 30 years experience of mir submersibles for the ocean operations. Deep Sea Res. Part II 155, 83–95 (2018).

Ogura, S. et al. Development of oil filled pressure compensated lithium-ion secondary battery for dsv shinkai 6500. In Oceans’ 04 MTS/IEEE Techno-Ocean’04 (IEEE Cat. No. 04CH37600), vol. 3, 1720–1726 (IEEE, 2004).

Lévêque, J. & Drogou, J. Operational overview of nautile deep submergence vehicle since 2001. new orleans, la, underwater intervention 2006. In Proc. of Underwater Intervention Conference. New Orleans, LA. Published by Marine Technology Society (2006).

Cui, W. et al. 7 000 m sea trials test of the deep manned submersible “Jiaolong’’. J. Ship Mech. 16, 1131–1143 (2012).

Hu, Z. & Cao, J. Development and application of manned deep diving technology. Strat. Study Chin. Acad. Eng. 21, 87–94 (2019).

Gertler, M. & Hagen, G. R. Standard Equations of Motion for Submarine Simulation (Tech Rep, 1967).

Feldman, J. DTNSRDC revised standard submarine equations of motion (David W (Ship Performance ..., Taylor Naval Ship Research and Development Center, 1979).

Park, J.-Y., Kim, N. & Shin, Y.-K. Experimental study on hydrodynamic coefficients for high-incidence-angle maneuver of a submarine. Int. J. Naval Archit. Ocean Eng. 9, 100–113 (2017).

Fossen, T. I. & Fjellstad, O.-E. Nonlinear modelling of marine vehicles in 6 degrees of freedom. Math. Model. Syst. 1, 17–27 (1995).

Liu, F. & Han, D. F. Study on motion simulation of hov. Adv. Mater. Res. 694, 158–162 (2013).

Deng, W. & Han, D. Study on simulation of remotely operated underwater vehicle spatial motion. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 12, 445–451 (2013).

Park, J. & Kim, N. Dynamics modeling of a semi-submersible autonomous underwater vehicle with a Towfish towed by a cable. Int. J. Naval Archit. Ocean Eng. 7, 409–425 (2015).

Kim, H., Ranmuthugala, D., Leong, Z. Q. & Chin, C. Six-dof simulations of an underwater vehicle undergoing straight line and steady turning manoeuvres. Ocean Eng. 150, 102–112 (2018).

Li, J.-H., Kim, M.-G., Kang, H., Lee, M.-J. & Cho, G. R. Uuv simulation modeling and its control method: Simulation and experimental studies. J. Marine Sci. Eng. 7, 89 (2019).

Herlambang, T. et al. Motion control design of unusaits auv using sliding pid. Nonlinear Dyn. Syst. Theory Int. J. Res. Surv. 20, 51–60 (2020).

Smallwood, D. A. & Whitcomb, L. L. Model-based dynamic positioning of underwater robotic vehicles: theory and experiment. IEEE J. Oceanic Eng. 29, 169–186 (2004).

Yang, X., Yan, J., Hua, C. & Guan, X. Trajectory tracking control of autonomous underwater vehicle with unknown parameters and external disturbances. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 51, 1054–1063 (2019).

Peng, Y., Guo, L., Meng, Q. & Chen, H. Research on hover control of auv uncertain stochastic nonlinear system based on constructive backstepping control strategy. IEEE Access 10, 50914–50924 (2022).

Guo, X., Yan, W. & Cui, R. Neural network-based nonlinear sliding-mode control for an auv without velocity measurements. Int. J. Control 92, 677–692 (2019).

Sun, B., Zhu, D. & Yang, S. X. An optimized fuzzy control algorithm for three-dimensional auv path planning. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 20, 597–610 (2018).

Shen, C. & Shi, Y. Distributed implementation of nonlinear model predictive control for auv trajectory tracking. Automatica 115, 108863 (2020).

Elmokadem, T., Zribi, M. & Youcef-Toumi, K. Trajectory tracking sliding mode control of underactuated auvs. Nonlinear Dyn. 84, 1079–1091 (2016).

Yan, Z., Wang, M. & Xu, J. Robust adaptive sliding mode control of underactuated autonomous underwater vehicles with uncertain dynamics. Ocean Eng. 173, 802–809 (2019).

Li, D. & Du, L. Auv trajectory tracking models and control strategies: A review. J. Marine Sci. Eng. 9, 1020 (2021).

Su, B., Wang, H. & Li, N. Event-triggered integral sliding mode fixed time control for trajectory tracking of autonomous underwater vehicle. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control. 43, 3483–3496 (2021).

Alattas, K. A. et al. Adaptive nonsingular terminal sliding mode control for performance improvement of perturbed nonlinear systems. Mathematics 10, 1064 (2022).

Vu, M. T. et al. Study on dynamic behavior of unmanned surface vehicle-linked unmanned underwater vehicle system for underwater exploration. Sensors 20, 1329 (2020).

Thanh, H. L. N. N., Vu, M. T., Mung, N. X., Nguyen, N. P. & Phuong, N. T. Perturbation observer-based robust control using a multiple sliding surfaces for nonlinear systems with influences of matched and unmatched uncertainties. Mathematics 8, 1371 (2020).

Rojsiraphisal, T. et al. Fast terminal sliding control of underactuated robotic systems based on disturbance observer with experimental validation. Mathematics 9, 1935 (2021).

Mofid, O. et al. Finite-time convergence of perturbed nonlinear systems using adaptive barrier-function nonsingular sliding mode control with experimental validation. J. Vib. Control 29, 3326–3339 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the China National Key Research and Development Program(2022YFC2805501) and the Program ***(2023-JCJQ-JJ-0402).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, D., Zhao, Q., He, C. et al. Research on the dynamic performance and motion control methods of deep-sea human occupied vehicles. Sci Rep 15, 5821 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90049-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90049-5