Abstract

Developing functional materials for optical remote control of magnetism can lead to faster, more efficient wireless data storage and sensing devices. In terms of desired material properties, this development requires the combined optimization of elastic interactions, low magnetic coercivity, and a narrow linewidth of ferromagnetic resonance to establish low-loss dynamic functionalities. A general pathway to achieve these requirements is still lacking. Here, we demonstrate that rare-earth trace element doping of an extrinsic multiferroic promotes strain mediated energy efficient remote control of static and dynamic magnetic properties induced by non-pulsed visible light. The strain under illumination arises from the photostrictive property of the ferroelectric substrate whereas the magnetism control originates from the enhanced magnetostrictive property of a rare-earth trace element doped ferromagnetic thin film. Combining the light-strain-magnetic interaction in the rare-earth doped extrinsic multiferroic provides a general approach for enhanced photo-magnetic elastic control extendable to optically tunable magnetic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Combining strain and non-pulsed light for the remote control of magnetism would be of great interest for energy efficient technologies of the digital world. Firstly, strain induced changes of magnetism are recognized to be of great potential for energy efficient issues in the field of materials sciences for digital information technologies such as information storage devices or sensors1,2,3,4. Secondly, the remote control of magnetism with non-pulsed sources of light such as the Sun, a continuous laser or a light emitting diode (LED), would present an energy saving alternative to the non energy efficient use of a current generated magnetic field5,6,7,8. Consequently, combining strain and non-pulsed light for the remote control of magnetic properties is of interest for energy savings. The strain and non-pulsed visible light combination for a control of static and dynamic magnetic properties was recently achieved for a family of materials named ferromagnetic/ferroelectric extrinsic multiferoics. Optimizing this energy efficient visible light control of magnetization is now required to develop its full potential, and that relies on materials science. Here, it is demonstrated that rare-earth trace element doping of an extrinsic multiferroic provides a pathway for a combined optimization of static and dynamic magnetic properties and their remote control through strain with continuous light, i.e. a solution to a complex material research paradigm.

Results and discussions

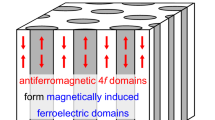

The extrinsic multiferroic considered here consists of a 5 nm magnetostrictive \(\hbox {Fe}_{80.9}\hbox {Ga}_{18.9}\hbox {La}_{0.2}\) (FeGaLa) thin film grown by RF magnetron sputtering on a (011)-Pb(\(\hbox {Mg}_{1/3}\hbox {Nb}_{2/3}\))\(\hbox {O}_3\)-Pb(Zr,Ti)\(\hbox {O}_3\) (PMN-PZT) piezoelectric substrate. \(\hbox {Fe}_{81}\hbox {Ga}_{19}\) (FeGa) is actually considered as an archetype of a modern magnetostrictive material exhibiting large magnetostriction and good tensile strength9,10,11,12. Furthermore, previous theoretical and experimental research works have shown that rare-earth trace element doping of Galfenol (\(\hbox {Fe}_{1-x}\hbox {Ga}_x\)) alloys may result in anisotropic modifications and magnetostrictive properties’ enhancement13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Among these different studies, an 0.2% La trace element doping of \(\hbox {Fe}_{83}\hbox {Ga}_{17}\) millimeter sized ribbons was shown to result in modifications of the magnetocrystalline anisotropy and an enhancement of the magnetostriction16,17. The PMN-PZT ferroelectric substrate was chosen as FeGa/PMN-PZT exhibits significant converse magneto-photostrictive static and dynamic coupling effects due to the PMN-PZT photostrictive properties under visible light6. This converse magneto-photostrictive effect (CMPE) is defined by the change of magnetic properties under the photostrictive effect, which can be schematically written as (light/mechanical) \(\times\) (mechanical/magnetic). CMPE was previously shown to occur in ferromagnetic/ferroelectric extrinsic multiferroics (ExMF) when light induces strain in the piezoelectric phase through the photostrictive effect6,20,21,22. Then, the dimensional changes were transferred to the magnetostrictive phase and, in turn, induced inverse magnetostriction, which translated into a change in magnetic properties.

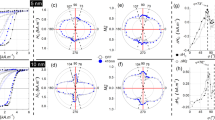

Magnetization reversals under the converse magneto-photostrictive effect. (a) FeGaLa/PMN-PZT zoomed hysteresis loops of the magnetization M, normalized to the saturated magnetization \(M_s\), measured in-plane with the magnetic field H, respectively along \(\varphi\) = \({0}^\circ\) (filled-in symbols) and \(\varphi\) = \({77.5}^\circ\) (not filled-in symbols), under the converse magneto-photostrictive effect CMPE, i.e., under the 410 nm illumination (blue circles), and in the dark state, OFF (black squares). Please note that the whole M-H loops can be found in the Supplementary Note 2. (b) FeGaLa/PMN-PZT coercive fields (\(H_{\textrm{c}}\)) polar plots under CMPE (blue filled-in circles) and in the dark state (black circles). The gray shaded area is an eye guide to indicate the \(H_{\textrm{c}}\) values previously reported for a 5 nm FeGa sample (from6). (c) FeGaLa/PMN-PZT normalized remanent magnetizations (\(M_{\textrm{R}}^\textrm{n}\)) polar plots under CMPE (blue filled-in circles) and in the dark state (black circles). The gray shaded area is an eye guide to indicate the \(M_{\textrm{R}}^\textrm{n}\) values previously reported for a 5 nm FeGa sample (from6). Dashed lines at \(77.5^\circ\) indicate the hard axis angular positions in the dark state. Continuous lines are guidelines to the eyes.

FeGaLa static magnetization reversals (MRev) properties were first characterized. A scheme of the experimental set-up can be found in the Supplementary Note 1. Figure 1a shows MRev loops in the dark state (i.e. light “OFF”) and under the illumination with the 410 nm laser diode, at two different angles \(\varphi\). \(\varphi\) is the angle between the applied magnetic field H and the [100] direction of the PMN-PZT substrate. Under CMPE, a decrease in the MRev loop area is observed along \(\varphi ={0}^\circ\) but an increase in the MRev loop area is observed along \(\varphi ={77.5}^\circ\). In fact, a 25% decrease of the coercivity and no significant changes of remanence are observed under illumination along \(\varphi ={0}^\circ\), whereas a 46% increase of the coercivity and a 135% increase of the remanence are observed under illumination along \(\varphi ={77.5}^\circ\). Thus, the observed CMPE is angular-dependent, not only in magnitude but also “in sign” (in the sense of a decrease or increase in MRev characteristic properties). A magnitude and sign angular dependent CMPE obtained under the same experimental conditions was previously reported in the absence of La, i.e. for a 5 nm FeGa thin film grown under the same experimental conditions on PMN-PZT6. It was shown to arise from the non-thermal dimension change of the PMN-PZT substrate under the laser illumination6.

In order to further understand the FeGaLa/PMN-PZT angular-dependent CMPE and how it may differ from that of FeGa/PMN-PZT, MRev angular dependencies were systematically probed. In the dark state, and under CMPE, \(H_{\textrm{c}}\) and \(M_{\textrm{R}}^\textrm{n}\) values have been obtained from each M-H loop as shown in Fig. 1b,c. In the dark state, both angular dependencies are typical of an uniaxial system as they exhibit two symmetrical lobes. The \(H_{\textrm{c}}\) and \(M_{\textrm{R}}^\textrm{n}\) minima define the hard axis position along \(\varphi =77.5^\circ\). Remarkably, previously reported results showed that a 5 nm FeGa thin film grown under the same experimental conditions on different substrates including the PMN-PZT substrate does not exhibit a dark state uniaxial anisotropy character but a cubic one6,11,23. The presence of a local maxima at \(\varphi ={90}^\circ\) in the FeGa \(H_{\textrm{c}}\) and \(M_{\textrm{R}}\) angular dependencies revealed the cubic anisotropy. For sake of comparison, these FeGa angular dependencies are also shown in Fig. 1b,c. Clearly, the La trace element doping of FeGa provides an uniaxial dark state anisotropy. It should be noted here that the FeGaLa uniaxial character is not driven by an epitaxial relationship with the PMN-PZT substrate. This was shown studying a 5 nm FeGaLa thin film grown on Glass (see the Supplementary Note 5 for more details).

The FeGaLa/PMN-PZT anisotropy is modified under CMPE as \(H_{\textrm{c}}\) and \(M_{\textrm{R}}^\textrm{n}\) minima along the hard axis at \(\varphi =77.5^\circ\) vanish under illumination. In a general manner, \(H_{\textrm{c}}\) and \(M_{\textrm{R}}^\textrm{n}\) angular dependencies as a whole are re-shaped revealing photostriction induced anisotropy changes.

To perform a quantitative analysis of the rare-earth trace element doping inclusion effect on the ExMF physical properties, a gain is now defined as:

with \(X^{\textrm{FeGaLa}}\) being the value of a given physical quantity for FeGaLa/PMN-PZT and \(X^{\textrm{FeGa}}\) being the value of the same physical quantity for FeGa/PMN-PZT. \(X^{\textrm{FeGaLa}}\), \(X^{\textrm{FeGa}}\) and the gain for different X physical quantities of interest are reported in Table 1.

It is of interest to analyse the coercivity gain along the easy axis as reducing \(H_{\textrm{c}}\) along an easy axis relates to an energy reduction needed to reverse a magnetization in its most stable state. The FeGaLa maximum value of the coercive field (\(H_{\textrm{c}}^{\textrm{max}}\)) in the dark state is 0.90 ± 0.01 kA \(\hbox {m}^{-1}\) and it is found along the uniaxial easy axis. The Gain when comparing the FeGa and FeGaLa coercivity maxima is −45% as reported in Table 1. Furthermore, the La doping results in a significant decrease of the FeGa/PMN-PZT coercivity over the whole angular range as shown in Fig. 1b.

Magnetic field dependencies of converse magnetophotostrictive coupling coefficients. The FeGaLa/PMN-PZT converse magneto-photostrictive coupling coefficient, \(\alpha _{\textrm{CMP}}^\mathrm {410 \, nm}\), along \(\varphi ={0}^\circ\) (filled-in blue squares) and \(\varphi =77.5^\circ\) (red squares), as estimated from the magnetization M versus magnetic field H data presented in Fig. 1. For a given angle, \(\alpha ^\downarrow _\textrm{ext}\) is the converse magneto-photostrictive coupling coefficient extremum value when H decreases. For a given angle, \(\alpha ^\uparrow _\textrm{ext}\) is the converse magneto-photostrictive coupling coefficient extremum value when H increases. \(\varphi\) is the angle between the applied magnetic field H and the [100] direction of the substrate.

In order to quantify the relative magnetization change under CMPE, a converse magneto-photostrictive coupling coefficient was recently proposed6. This coefficient allows an evaluation of the CMPE efficiency, provides a convenient approach for comparing different materials. Here, it can be used to assess the effect of rare-earth trace element doping on the CMPE efficiency for magnetization changes. This converse magneto-photostrictive coupling coefficient \(\alpha _{\textrm{CMP}}^\lambda\) is defined in a similar way as the converse magneto-electric coefficient1,2,3,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32 as below:

with \(\Delta {M(H)}\), the change in magnetization at a field H under a change of light intensity \(\Delta {I}\) at a wavelength \(\lambda\). In our experimental work, \(\alpha _{\textrm{CMP}}^\mathrm {410 \, nm} (H)\) can be determined with \(I_1=0.6\) W.\(\hbox {cm}^{-2}\) and \(I_0=0\). The relative change in magnetization is directly computed from the measured MRev loops in the dark state and under CMPE. Figure 2 shows \(\alpha _{\textrm{CMP}}^\mathrm {410 \, nm} (H)\) at \(0^\circ\) and \(77.5^\circ\), which were determined using the M-H loops shown in Fig. 1a. For both angles, \(\alpha _{\textrm{CMP}}^\mathrm {410 \, nm} (H)\) exhibits two extrema of opposite signs. The first (second) extremum, \(\alpha ^\downarrow _\textrm{ext}\) (\(\alpha ^\uparrow _\textrm{ext}\)), occurs when H decreases (increases) as shown in Fig. 2. Over the full angular range, \(\alpha ^\downarrow _\textrm{ext}(\varphi )\) and \(\alpha ^\uparrow _\textrm{ext}(\varphi )\) are of the same magnitude within experimental uncertainty but of opposite sign as shown in Fig. 3a. This is a consequence of the M-H loops symmetry.

Angular dependencies of converse magnetophotostrictive coupling coefficients and their maxima values. (a) Angular dependencies of the FeGaLa/PMN-PZT converse magneto-photostrictive coupling coefficient extremum value when H decreases, \(\alpha ^\downarrow _\textrm{ext}\) (red squares), and when H increases, \(\alpha ^\uparrow _\textrm{ext}\) (filled-in blue squares). (b) Angular dependencies of the converse magneto-photostrictive coupling coefficient maximum value, \(\alpha _{\textrm{CMP,max}}^\mathrm {410 \, nm}\), for the FeGaLa/PMN-PZT sample (blue filled-in circles) and for the FeGa/PMN-PZT sample (black circles delimiting the gray shaded area). The FeGa/PMN-PZT sample data were previously reported in6. Dashed lines at \(77.5^\circ\) indicate the hard axis angular positions in the dark state. Continuous lines are guidelines to the eyes. \(\varphi\) is the angle between the applied magnetic field H and the [100] direction of the PMN-PZT. PMN-PZT is the (011)-Pb(\(\hbox {Mg}_{1/3}\hbox {Nb}_{2/3}\))\(\hbox {O}_3\)-Pb(Zr,Ti)\(\hbox {O}_3\) substrate.

For a given angle \(\varphi\), the maximum obtainable CMPE on magnetization is rendered by the maximum value of the \(\alpha _{\textrm{CMP}}^\mathrm {410 \, nm} (H)\), defined as:

The magnitude of the \(\alpha _{\textrm{CMP,max}}^\mathrm {410 \, nm}\) angular dependence is then proportional to the angular-dependent maximum change in magnetization inferred by the illumination as stated by Eq. (2). Over the whole angular range, FeGaLa \(\alpha _{\textrm{CMP,max}}^\mathrm {410 \, nm}\) values are larger than previously reported FeGa \(\alpha _{\textrm{CMP,max}}^\mathrm {410 \, nm}\) ones as shown in Fig. 3b. It reveals that the gain via the rare-earth trace element doping is significant for any angle. In the vicinity of the easy axis, the FeGaLa maximum value of \(\alpha _{\textrm{CMP,max}}^\mathrm {410 \, nm}\) is (21.3 ± 0.1)\(10^{-5}\) s \(\hbox {A}^{-1}\). This maximum value can be compared to that of FeGa which is found in the vicinity of its major easy axis as reported in Table 1. The gain for \(\alpha _{\textrm{CMP,max}}^\mathrm {410 \, nm}\) maximum reaches +48%.

The rare-earth trace element doping of the ExMF significantly modifies the static properties in the dark state and under CMPE. Upon this doping, the anisotropy character is modified towards uniaxiality, the easy axis coercivity is reduced and magnetization changes due to CMPE are enhanced. Static modifications are related to changes of the anisotropy energy landscape, among which the magnetostrictive part plays a keyrole in extrinsic multiferroic MRev. Here, the magnetophotostrictive coefficient gain resulting from the La trace element doping is +33% (cf. Supplementary Note 3 for magnetostrictive measurements). In a general manner, previous studies have revealed that rare-earth trace element dopings result in significant modifications of the anisotropy constant and magnetostriction. However, these studies did not address the consequence of that on MRev properties or on their control with CMPE. The reasons reported for the large increase in the magnetostriction of Fe-Ga alloy caused by the doping of a small amount of rare-earth elements rely on an induced (001) orientation texture, and on the lattice distortion resulting in localized magnetocrystalline anisotropy fields. Demonstrating the general nature of the phenomena, a combination of these two origins leading to magnetostriction enhancement was previously shown in different experimental studies addressing rare-earths trace element doping of Galfenol, including doping by Dy15, Tb13,14,19, Pr18, La16,17,18, Sm18, Y18, Gd16, Lu16, Ce33 and Er34. Beyond Galfenol, rare-earth trace element doping was recently shown to also enhance the of Alfenol (\(\hbox {Fe}_{1-x}\hbox {Al}_x\)) magnetostriction35,36,37, and the static magnetic properties of an Alfenol based ExMF can be controled under CMPE20. The trace element doping with various rare-earths provides a general pathway to enhance the magnetostriction in different ExMFs. Beyond magnetostrictive enhancements, static magnetic properties and their remote control under visible continuous light are here shown to be optimized by the ExMF rare-earth trace element doping, encouraging the development of novel heterostructures based on this approach for energy-efficient remote controlled magnetic materials.

Ferromagnetic resonance spectra under the converse magneto-photostrictive effect. In-plane field-sweep FMR spectra for the FeGaLa sample and the FeGa sample measured at 9.3 GHz under the converse magneto-photostrictive effect (CMPE) induced by the light emitting diode illumination (blue non-filled circles for the FeGaLa sample, blue non-filled triangles for the FeGa sample) and in the dark state (black filled circles for the FeGaLa sample, black filled triangles for the FeGa sample), along \(\varphi ={0}^\circ\). \(\varphi\) is the angle between the applied magnetic field H and the [100] direction of the substrate.

To analyse rare-earth trace element doping effects not only on static magnetic properties but also on dynamic magnetic properties, Ferromagnetic Resonance (FMR) spectra were acquired in the dark state and under CMPE. The ExMF was illuminated with an intensity of 7 W \(\hbox {cm}^{-2}\) from a 405 nm LED or with the laser used for static measurements. It should be noted here that the LED could not be used for static measurements due to space restrictions within the MOKE apparatus. The PMN-PZT strain under the LED illumination was measured using a strain gauge. It is found to be equal to (0.245 ± 0.003)%. For comparison, the magnitude of previously reported values of the PMN-PZT piezoelectric coefficient is \(\approx\) 1500 pm/V. Thus, for the 0.3 mm PMN-PZT used in our study, the resulting strain is determined as 0.1% under 200 V (or 0.2% under 400 V). Thus, strains obtained under illuminations and strains obtained under a few hundred volts are of similar magnitudes for PMN-PZT substrates. Figure 4 shows FeGaLa/PMN-PZT FMR spectra measured with the dc external magnetic field applied along \(\varphi ={0}^\circ\) (while the magnetic component of the microwave field was perpendicular to the dc field). For the sake of comparison, previously reported FeGa/PMN-PZT FMR spectra6 are also shown in Fig. 4. The FeGaLa dark state FMR measurement reveals a lineshape with a resonance field, \(H_{\textrm{res}}\) (the external magnetic field at which the power absorption spectrum dI/dH crosses zero, i.e. maximum power absorption), at 69.6 kA \(\hbox {m}^{-1}\). When illuminated with the laser, no significant modifications of the FMR spectra were observed. However, significant modifications were obtained under the LED illumination as shown in Fig. 4. Under CMPE, \(H_{\textrm{res}}\) shifts to 75.9 kA \(\hbox {m}^{-1}\), i.e. a 9.0% relative shift of \(H_{\textrm{res}}\) from the dark state value.

FeGaLa/PMN-PZT absolute and relative \(H_{\textrm{res}}\) shifts under CMPE are greater than FeGa/PMN-PZT ones as reported in Table 1. Thus, the trace element doping results in an optimized control of the resonant field by CMPE. The gain for the relative resonant field shift under CMPE is +58%. The FMR linewidth (LW) is a critical parameter which has to be as small as possible to reduce microwave losses in magnetic materials38. Here, a 9.2 ± 0.3 kA \(\hbox {m}^{-1}\) FeGaLa LW is measured. It is smaller than the 23.8 ± 0.3 kA \(\hbox {m}^{-1}\) FeGa LW. Thus, the LW gain is −61% showing a significant improvement in the reduction of the relaxation as reported in Table 1. Furthermore, this gain is conserved under CMPE as the LW is not modified under illumination. The rare-earth trace element doping enhances the optical control of the resonant field and reduces microwave losses.

Conclusion

Our study reveals that rare-earth trace element doping in an extrinsic multiferroic provides a pathway to solve the paradigm of static and dynamic magnetic properties optimization, and their remote control with the converse magneto-photostrictive effect under non continuous visible light. Therefore, a combined optimization of materials properties is achieved, including the search for ultrathin ferromagnetic materials to achieve interfacial and size effects, the search for high magnetostrictive coefficient to improve the magnetization change under strain, the search for low coercivity to promote an energy efficient static control, the search for a small linewidth ferromagnetic resonance at GHz frequencies to reduce microwave losses. The findings presented in our manuscript provide a general path to be applied in a variety of rare earth doped extrinsic multiferroics, when the magnetostrictive layer is significantly modified through rare-earth trace element doping via lattice distortions. In the paradigm of finding a general pathway for tuning and optimizing materials as an essential brick for a combined strain and non pulsed light driven energy efficient remote control of magnetism, the potential here given can be used in wireless and energy efficient systems to control magnetic properties and tunable RF/microwave devices.

Supplementary Information

Scheme of the experimental set-up for static measurements; entire magnetization reversals loop and magnetostriction measurements of a 5 nm \(\hbox {Fe}_{80.9}\hbox {Ga}_{18.9}\hbox {La}_{0.2}\) thin film; angular dependence of the coercive field for a 5 nm FeGaLa thin film deposited under different growth conditions; angular dependence of the coercive field for a 5 nm FeGaLa thin film deposited on Glass can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Methods

Sample preparation

The samples were prepared by depositing the magnetostrictive \(\hbox {Fe}_{81}\hbox {Ga}_{19}\hbox {La}_{0.2}\) thin films onto the PMN-PZT substrates, using radio-frequency magnetron sputtering. PMN-PZT rhombohedral single crystals grown by solid-state crystal growth are commercially available as “CPSC160-95” from Ceracomp Co. Ltd., Korea39. The PMN-PZT substrates used in this study had physical dimensions of 0.3 mm thick, 3 mm wide and 5 mm long. Initially, the PMN-PZT substrates are cleaned with ethanol and acetone. A \(\hbox {Fe}_{81}\hbox {Ga}_{19}\hbox {La}_{0.2}\) polycrystalline target with a diameter of 3 inches is used in an Oerlikon Leybold Univex 350 sputtering system. The base pressure prior to the film deposition is typically \(10^{-7}\) mbar. \(\hbox {Fe}_{81}\hbox {Ga}_{19}\hbox {La}_{0.2}\) thin films are deposited onto the PMN-PZT beams at room temperature using 100 W of deposition power and about 10 sccm argon flow rate. The stack was capped in situ with a 10 nm-thick Ta layer to protect the \(\hbox {Fe}_{81}\hbox {Ga}_{19}\hbox {La}_{0.2}\) layer against oxidation. The growth was carried out under an in-plane magnetic field \(H_{\textrm{dep}}\) = 2.4 kA \(\hbox {m}^{-1}\) along the [100] direction of the PMN-PZT substrate. Information on the poling procedure, growth conditions, growth preparations can also be found in previous publications6,11,23. For information, the coercive field angular dependence for another growth condition is reported in the Supplementary Note 4.

Static magnetic measurements

Magnetic measurements at room temperature were determined using the magneto-optic Kerr effect in a wide-field Kerr microscope from Evico Magnetics40. In order to improve the signal-to-noise ratio, any MRev loop presented in this manuscript results from the average of 5 MRev loops acquired during 150 s. The CMPE control of static magnetic properties was studied by illuminating the samples with an intensity \(I_1\) of 0.6 W.\(\hbox {cm}^{-2}\) from a 410 nm laser diode. The laser spot size is (570\(\times\)1776) \(\upmu \textrm{m}^2\) (FWHM) and the incident angle of the laser beam on the sample surface is \(20^\circ\). The samples were illuminated on the backside (i.e. the substrate side). For further information, a scheme of the experimental setup can be found in the supplementary information (see Supplementary Note 1). When the substrate was illuminated, the magnetic measurements were offset by a delay time of 60 s. Increasing the delay time did not change the results of the static magnetic measurements presented in this manuscript. Information on the static magnetic measurements method can also be found in6.

Dynamic magnetic measurements

An Elesxys 500 Bruker electron paramagnetic resonance spectrometer operating at X-band (9.3 GHz) was used to characterize the microwave performance of FeGa /PMN-PZT heterostructures. For dynamic measurements, the CMPE was studied by illuminating the samples with the laser diode (the one previously described in the Static magnetic measurements) and it was also studied by illuminating the samples with a LED. The LED wavelength is 405 nm and the intensity of the LED illumination is 7 W \(\hbox {cm}^{-2}\). The incident angle of the beam on the sample surface is \(0^\circ\) (i.e. along the surface normal). The samples were illuminated on the backside (i.e. the substrate side). When the substrate was illuminated, the magnetic measurements were offset by a delay time of 360 s. Increasing the delay time did not change significantly the results of the dynamic magnetic measurements presented in this manuscript. Information on the Dynamic magnetic measurements method can also be found in6.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bukharaev, A. A., Zvezdin, A. K., Pyatakov, A. P. & Fetisov, Y. K. Straintronics: a new trend in micro- and nanoelectronics and materials science. Phys. Uspekhi 61, 1175. https://doi.org/10.3367/ufne.2018.01.038279 (2018).

D’Souza, N. et al. Energy-efficient switching of nanomagnets for computing: straintronics and other methodologies. Nanotechnology 29, 442001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6528/aad65d (2018).

Bandyopadhyay, S., Atulasimha, J. & Barman, A. Magnetic straintronics: Manipulating the magnetization of magnetostrictive nanomagnets with strain for energy-efficient applications. Appl. Phys. Rev. 8, 041323. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0062993 (2021).

Gradauskaite, E., Meisenheimer, P., Müller, M., Heron, J. & Trassin, M. Multiferroic heterostructures for spintronics. Phys. Sci. Rev. 6, 20190072. https://doi.org/10.1515/psr-2019-0072 (2021).

Fang, N., Wu, C., Zhang, Y., Li, Z. & Zhou, Z. Perspectives: Light control of magnetism and device development. ACS Nano 18, 8600. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.3c13002 (2024).

Liparo, M. et al. Static and dynamic magnetization control of extrinsic multiferroics by the converse magneto-photostrictive effect. Commun. Phys. 6, 356. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-023-01479-4 (2023).

Fashami, M. S., Atulasimha, J. & Bandyopadhyay, S. Magnetization dynamics, throughput and energy dissipation in a universal multiferroic nanomagnetic logic gate with fan-in and fan-out. Nanotechnology 23, 105201. https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-4484/23/10/105201 (2012).

Makhort, A. et al. Photovoltaic-ferroelectric materials for the realization of all-optical devices. Adv. Opt. Mater. 10, 2102353. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202102353 (2022).

Clark, A. E., Restorff, J. B., Wun-Fogle, M., Lograsso, T. A. & Schlagel, D. L. Magnetostrictive properties of body-centered cubic Fe-Ga and Fe-Ga-Al alloys. IEEE Trans. Magn. 36, 3238. https://doi.org/10.1109/20.908752 (2000).

Atulasimha, J. & Flatau, A. B. A review of magnetostrictive iron–gallium alloys. Smart Mater. Struct. 20, 043001. https://doi.org/10.1088/0964-1726/20/4/043001 (2011).

Jahjah, W. et al. Thickness dependence of magnetization reversal and magnetostriction in FeGa thin films. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 024020. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.12.024020 (2019).

Legall, F. et al. Magnetization reversals of \(\text{ Fe}_{81}\text{ Ga}_{19}\)-based flexible thin films under multiaxial mechanical stress. Phys. Rev. Appl. 15, 044028. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.15.044028 (2021).

Wu, W., Liu, J., Jiang, C. & Xu, H. Giant magnetostriction in Tb-doped \(\text{ Fe}_{83}\text{ Ga}_{17}\) melt-spun ribbons. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 262403. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4851216 (2013).

Fitchorov, T. I. et al. Thermally driven large magnetoresistance and magnetostriction in multifunctional magnetic fega-tb alloys. Acta Mater. 73, 19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2014.03.053 (2014).

Jin, T., Wu, W. & Jiang, C. Improved magnetostriction of Dy-doped \(\text{ Fe}_{83}\text{ Ga}_{17}\) melt-spun ribbons. Scripta Mater. 74, 100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scriptamat.2013.11.010 (2014).

He, Y. et al. Giant heterogeneous magnetostriction in Fe-Ga alloys: Effect of trace element doping. Acta Mater. 109, 177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2016.02.056 (2016).

He, Y. et al. Interaction of trace rare-earth dopants and nanoheterogeneities induces giant magnetostriction in Fe-Ga alloys. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1800858. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201800858 (2018).

Zhao, X. et al. The origin of large magnetostrictive properties of rare earth doped Fe-Ga as-cast alloys. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 514, 167289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmmm.2020.167289 (2020).

He, Z. et al. Enhanced magnetostriction of rolled (\(\text{ Fe}_{81}\text{ Ga}_{19})_{99.93}\text{ Tb}_{0.07}\) thin sheet by synergy strategy of secondary recrystallization and trace Tb-doping. J. Alloys Compounds 942, 169108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.169108 (2023).

Ochoa, D. A. et al. Reversible optical control of magnetism in engineered artificial multiferroics. Nanoscale 16, 4900. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3NR05520E (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Light modulation of magnetization switching in PMN-PT/Ni heterostructure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 132405. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5145284 (2020).

Iurchuk, V. et al. Optical writing of magnetic properties by remanent photostriction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 107403. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.117.107403 (2016).

Jahjah, W. et al. Electrical manipulation of magnetic anisotropy in a \(\text{ Fe}_{81}\text{ Ga}_{19}\text{/Pb(Mg }_{1/3}\text{ Nb}_{2/3})\text{ O}_3\text{-Pb(Zr }_x \text{ Ti}_{1-x})\text{ O}_3\) magnetoelectric multiferroic composite. Phys. Rev. Appl. 13, 034015. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.13.034015 (2020).

Thiele, C., Dörr, K., Bilani, O., Rödel, J. & Schultz, L. Influence of strain on the magnetization and magnetoelectric effect in \(\text{ La}_{0.7}\text{ A}_{0.3}\text{ MnO}_3/\)PMN-PT(001). Phys. Rev. B 75, 054408. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.75.054408 (2007).

Yang, J. J. et al. Electric field manipulation of magnetization at room temperature in multiferroic \(\text{ CoFe}_2\text{ O}_4\text{/Pb }(\text{ Mg}_{1/3}\text{ Nb}_{2/3})_{0.7}\text{ Ti}_{0.3}\text{ O}_3\) heterostructures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 212504. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3143622 (2009).

Wu, T. et al. Giant electric-field-induced reversible and permanent magnetization reorientation on magnetoelectric Ni \(/\) (001) Pb(\(\text{ Mg}_{1/3}\text{ Nb}_{2/3})_{0.7}\text{ Ti}_{0.3}\text{ O}_3\) heterostructure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 012504. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3534788 (2011).

Zhang, S. et al. Giant electrical modulation of magnetization in \(\text{ Co}_{40}\text{ Fe}_{40}\text{ B}_{20}\text{/Pb }(\text{ Mg}_{1/3}\text{ Nb}_{2/3})_{0.7}\text{ Ti}_{0.3}\text{ O}_{3}\)(011) heterostructure. Sci. Rep. 4, 3727. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03727 (2014).

Nan, T. et al. Quantification of strain and charge co-mediated magnetoelectric coupling on ultra-thin Permalloy/PMN-PT interface. Sci. Rep. 4, 3688. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03688 (2014).

Alberca, A. et al. Phase separation enhanced magneto-electric coupling in \(\text{ La}_{0.7}\text{ Ca}_{0.3}\text{ MnO}_3\)/\(\text{ BaTiO}_3\) ultra-thin films. Sci. Rep. 5, 17926. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep17926 (2015).

Yang, C. et al. Giant Converse Magnetoelectric Effect in PZT/FeCuNbSiB/FeGa/FeCuNbSiB/PZT Laminates Without Magnetic Bias Field. IEEE Trans. Magn. 51, 1. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMAG.2015.2435010 (2015).

Staruch, M. et al. Reversible strain control of magnetic anisotropy in magnetoelectric heterostructures at room temperature. Sci. Rep. 6, 37429. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37429 (2016).

Biswas, A. K., Ahmad, H., Atulasimha, J. & Bandyopadhyay, S. Experimental Demonstration of Complete \(180^\circ\) Reversal of Magnetization in Isolated Co Nanomagnets on a PMN–PT Substrate with Voltage Generated Strain. Nano Lett. 17, 3478 (2017).

Baker, A. A. et al. Enhanced magnetostriction through dilute Ce doping of Fe-Ga. Phys. Rev. Mater. 7, 014406. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevMaterials.7.014406 (2023).

Gao, C., Zou, H., Pan, H. & Shuai, C. Magnetostrictive improvement in er-doped biodegradable \(\text{ Fe}_{81}\text{ Ga}_{19}\) alloys manufactured by selective laser melting. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 24, 8669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.05.114 (2023).

Uribe-Chavira, J. et al. X-ray diffraction analysis by rietveld refinement of FeAl alloys doped with terbium and its correlation with magnetostriction. J. Rare Earths 41, 1217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jre.2022.07.006 (2023).

Wang, R., Tian, X., Yao, Z., Kong, M. & Wang, Y. Effects of Rare-Earth element dy doping on magnetostrictive properties of Fe-Al solid solution. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 32, 2273 (2023).

Wang, R., Tian, X., Yao, Z., Zhao, X. & Hao, H. Influence of rare earth element terbium doping on microstructure and magnetostrictive properties of \(\text{ Fe}_{81}\text{ Al}_{19}\) alloy. J. Rare Earths 40, 451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jre.2020.12.009 (2022).

Guo, X. et al. Annealing enhanced ferromagnetic resonance of thickness-dependent fega films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 120, 202402. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0090880 (2022).

Ceracomp Co. Ltd., Korea, http://www.ceracomp.com.

Evico Magnetics, Germany, http://www.evico-magnetics.de.

Acknowledgements

Authors acknowledge the financial support from the South African National Research Foundation (Grant No: 88080) and the URC/FRC, University of Johannesburg (UJ), South Africa. Authors wish to acknowledge the support of University of Brest in funding ML’s Ph.D. Authors wish to acknowledge the technical support of G. Mignot for MOKE and photostrain experimental set-ups.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.T.D, A.F, J-Ph.J, D.S conceived and directed this project. D.T.D, A.F, J-Ph.J, M.L, D.S realized the samples. D.T.D, M.D, A.F, J-Ph.J, Y.LG, M.L, A.R.E.P, C.J.S, D.S performed and analyzed static measurements. B.K., D.T.D, M.L performed and analysed photostrain measurements. D.T.D, A.F, J-Ph.J, M.L, G.S, D.S, performed and analyzed dynamic measurements. This manuscript was mainly prepared by D.T.D, A.F, J-Ph.J, M.L, D.S and all authors contributed to the discussion of the results and the text.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liparo, M., Jay, JP., Kundys, B. et al. Rare earth trace element doping of extrinsic multiferroics for an energy efficient remote control of magnetic properties. Sci Rep 15, 5788 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90205-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90205-x

This article is cited by

-

Synthesis, Structural and Multiferroic Properties of Yttrium-Titanium co-substitution BiFeO3 Ceramics

Journal of Superconductivity and Novel Magnetism (2025)