Abstract

The increasing concern over chronic respiratory diseases (CRDs) caused by industrial pollution from particulate matter, gases, and fumes (PMGF) highlights the critical need for a comprehensive understanding of its spatiotemporal trends to mitigate work-related respiratory disorders effectively. Data from the Global Burden of Disease 2021 were extracted to analyze the mortality of occupational PMGF-attributed CRD. The joinpoint regression model was employed to illustrate its trends in age-standardized mortality rate (ASMR) from 1990 to 2021, facilitating the calculation of average annual percentage changes (AAPCs). The age-period-cohort (APC) model was used to isolate and quantify the contributions of age, period, and cohort effects to the observed temporal trends in mortality rates. From 1990 to 2021, the ASMR of PMGF attributed-CRD decreased from 21.74 (13.34, 30.11) to 12.84 (7.80, 18.20), with an AAPC of -1.69 (-1.82, -1.56). A sharper negative AAPC was detected in females, pneumoconiosis cases, middle SDI region, and Southeast Asia, East Asia & Oceania. In addition, some positive AAPCs appeared in low-middle SDI, South Asia, and high-income nations for females. Although the Western Pacific witnessed the steepest ASMR declines, a rising ASMR was noted in Nordic and American female COPD patients, with increasing pneumoconiosis ASMR in the Middle East and North Africa. The total age-specific mortality increased, with a decrease observed in both period and cohort effect, more pronounced among females. COPD mortality exhibited a steeper decline than pneumoconiosis in the period and cohort RR, but not for females. The low-middle SDI region and South Asia led in age-specific CRD mortality, whereas the period and cohort RR experienced the largest reduction in the high-middle SDI region and Southeast Asia, East Asia & Oceania. However, the period and cohort RR showed the weakest attenuation in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Over the past 32 years, progress has been made in managing industrial PMGF pollution-related CRD; however, challenges persist, particularly among sub-Saharan Africans, South Asian women, pneumoconiosis cases in the Middle East and North Africa, and female COPD patients in high-income nations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic respiratory disease (CRD) is a category of progressive pulmonary disorders characterized by partially alleviated but progressively worsening dyspnea1. There has been growing attention to CRD as an essential public health issue, particularly considering the substantial disease burden it has placed on low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)2. An estimated 77.6 million newly diagnosed CRD cases were recorded globally in 2019, representing a 49.0% rise from 1990. In the same year, CRD was responsible for 4 million deaths, making it the third leading cause of death, and contributed to 103.5 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), which accounted for 4.1% of the overall DALYs worldwide3. In 2015, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 3.4 called for a one-third decrease in premature mortality from non-communicable diseases, including CRD, by 20304. To achieve this, the World Health Organization (WHO) has created multiple alliances, notably the Global Alliance against Chronic Respiratory Diseases (GARD)5.

The impact of occupational pollutants, such as dust, particulate matter, aerosols, and smoke, in the development of CRD, is gaining increasing scholarly interest. Earlier research has evidenced that prolonged exposure to harmful particles and gases from occupational sources, mainly produced in industries like mining, manufacturing, and agriculture, would increase the risk of respiratory disorders6. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and pneumoconiosis are currently the two most broadly regulated CRDs attributable to industrial gaseous pollutants, despite differences in their pathophysiological mechanisms. The pathogenesis of COPD is commonly understood to start with the inhalation of toxicants that induce airway epithelial damage and chronic inflammation, accompanied by oxidative stress and a protease-antiprotease imbalance, further exacerbating airway injury, leading to its remodeling and obstruction7. The onset of pneumoconiosis, on the other hand, is initiated by the inhalation of harmful particles, triggering an inflammatory response that leads to lung interstitial destruction, fibroblast activation, and scar tissue formation, ultimately impairing the gas exchange function of the alveolar walls8. Actions to control CRD among occupational groups are extremely important, as they not only affect both individual health and well-being but also indirectly impact national economic efficiency and social welfare expenditures.

To assist health authorities in devising more precise and efficient strategies, conducting systematic research on the disease burden of occupational particulate matter, gases, and fumes (PMGF) is crucial for evaluating the threats posed to workers’ respiratory health. Although previous studies have investigated the impact of industrial PMGF on COPD, some information remains to be further explored, e.g. the burden of pneumoconiosis under the PMGF context, and how differences in physical function, medical levels at different times, and exposure variations across generations affect the CRD burden in occupational groups9. Therefore, our research aims to comprehensively examine the trends in CRD mortality, including COPD and pneumoconiosis, due to occupational PMGF exposure over the past 32 years, using mortality data from 204 countries or territories provided by the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021) database, and to quantify the age-period-cohort effects on mortality.

Materials and methods

Original data

Information on our current research was publicly retrieved from GBD 2021 globally between 1990 and 2021 (https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/)10. Relevant data were collected to evaluate the burden of CRD attributed to occupational PMGF, with detailed guidelines for extraction illustrated in Additional File 1. In the GBD 2021 risk hierarchy, the “Risk” item included “Environmental/occupational risks”, “Behavioral risks”, and “Metabolic risks” at the primary level, which were further broken down into 20 secondary subtypes. Under “Occupational risks”, a secondary factor, “Occupational particulate matter, gases, and fumes (PMGF)” was selected as a tertiary risk for our targeted risk factor. The correspondent secondary cause “Chronic respiratory diseases (CRD)”, along with its subtypes “Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)” (J41-J44) and “Pneumoconiosis” (J60-J65), were identified for our targeted diseases within the primary category “Non-communicable diseases”, as classified by the Tenth Edition of International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) system11.

Statistical description

GBD 2021 provided the age-standardized mortality rate (ASMR) to analyze disease burden across genders, ages, calendar years, and regions, accounting for populations across the full age range. However, since our study focused exclusively on individuals aged 25 years and older, the ASMRs with their 95% uncertainty intervals (UIs) were recalculated using Monte Carlo simulation, with the GBD Standard Population as a reference12. The socio-demographic index (SDI) was adopted to compare the burden between regions at different socio-economic levels. This composite measure integrated the total fertility rate in females under 25, the educational attainment of individuals aged 15 and older, and lag-distributed income per capita13. Therefore, 204 countries and territories were classified into five SDI quintiles: low, low-middle, middle, high-middle, and high. Detailed historical SDI records for each country and territory were provided in Table S1. Considering that socio-economic similarities and geographical proximity may have contributed to potential health inequalities, 204 countries and territories were also grouped into seven GBD super regions based on epidemiological similarity and geographic closeness: Central Europe; Eastern Europe & Central Asia; High-income; Latin America & Caribbean; North Africa & Middle East; South Asia; South-East Asia, East Asia & Oceania and Sub-Saharan Africa14.

Statistical interference

The average annual percentage changes (AAPCs) were calculated using joinpoint regression analysis to assess temporal trends of ASMR within predetermined intervals. Optimal joinpoints were identified based on changes in slopes and connected through a series of log-linear models, allowing for a maximum of five joinpoints15. The equation of joinpoint regression was listed as follows:

where k represented number of turning points, τk represented unknown turning points, β0 represented constant, β1 represented regression coefficient, δk represented regression coefficient of the kth piecewise function. Only when the 95% confidence interval (CI) did not include 0 would AAPC be considered statistically significant.

To address the collinearity while separately assessing the effects of age, period, and cohort on mortality, the age-period-cohort (APC) model was employed to parameterize these three factors as independent variables16. The age effect, reflecting age-related physiological and pathological changes, was assessed through a longitudinal age curve fitted with age-specific rates relative to a reference cohort and adjusted for period deviations. The period effect, reflecting changes in mortality due to human factors such as effective treatments and screening programs, was assessed using a period rate ratio (RR), which compared age-specific rates in a specified period to those in a reference period. The cohort effect, reflecting generational differences in mortality due to lifestyle shifts or varying exposures to risk factors, such as changes in dietary patterns or living environments, was assessed using a cohort RR, which compared age-specific rates of a given cohort to those of a reference cohort. Net drift reflected the annual percentage change in the overall rate, while local drift reflected the annual percentage change in the age-specific rate. The population and mortality data were organized into 5-year age groups, ranging from the 25–29 age group to the 90–94 age group, with an additional 95 + age group. The data were also arranged into consecutive 5-year periods, from 1992 to 1996 to 2017–2021, and 5-year cohorts, from 1897 to 1902 to 1987–1992. The equation of the APC model was listed as follows:

where M represented the mortality for the ith age group during the jth period; \(\:{\alpha\:}_{i}\),\(\:\:{\beta\:}_{j}\) and \(\:{\gamma\:}_{k}\:\)represented the age, period and cohort effects, respectively; µ and ε represented the intercept and residual, respectively. The statistical analysis was performed by R version 4.3.3 software (Institute for Statistics & Mathematics, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Trends of occupational PMGF-attributed CRD mortality from 1990 to 2021

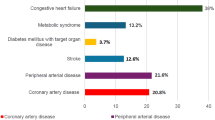

As detailed in Table 1, from 1990 to 2021, the total number of CRD deaths attributed to occupational PMGF exposure increased from 430,821 (263,222, 597,552) to 590,055 (357,752, 836,205), while the ASMR significantly decreased from 21.74 (13.34, 30.11) to 12.84 (7.80, 18.20), with an AAPC on ASMR of -1.69 (-1.82, -1.56) (P < 0.001); the death cases surged across most subgroups but showed a decline in the subgroups of pneumoconiosis, high-middle SDI and Central Europe, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia; a sharper negative AAPC on ASMR was detected in females than in males (-2.00 (-2.16, -1.83) vs. -1.64 (-1.82, -1.46), both P < 0.001), and in pneumoconiosis compared to COPD (-3.33 (-3.49, -3.18) vs. -1.67 (-1.80, -1.55), both P < 0.001); amidst regional divisions, the middle SDI and Southeast Asia, East Asia, and Oceania exhibited the greatest reductions, with AAPCs of -2.75 (-3.03, -2.47) and − 3.23 (-3.55, -2.91) (both P < 0.001), respectively. As reported in Tables S1 & S2, a greater negative AAPC was observed in females than in males only in the subgroups of COPD (-2.00 (-2.16, -1.84) vs. -1.61 (-1.80, -1.42)), middle SDI (-3.50 (-3.82, -3.17) vs. -2.26 (-2.49, -2.02)), high-middle SDI (-2.99 (-3.25, -2.74) vs. -2.61 (-2.87, -2.36)), Southeast Asia, East Asia, and Oceania (-3.83 (-4.23, -3.42) vs. -2.84 (-3.22, -2.47)) (all P < 0.001); besides, positive but insignificant AAPCs were seen in regions of low-middle SDI (0.15 (-0.33, 0.62)) (P = 0.545), high-income (0.25 (-0.02, 0.53)) (P = 0.065), and South Asia (0.06 (-0.49, 0.60)) (P = 0.843) for females.

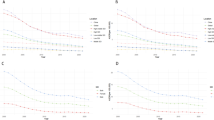

As shown in Fig. 1A and B, from 1990 to 2021, China, Thailand, and several Central and Eastern European nations witnessed the steepest declines in the ASMR of PMGF-attributed CRD, with AAPC values classified in the first octile (< -2.85 for males and < -2.47 for females); the downward ASMR among males from Australia and very few Western European nations, as well as among females from Japan and South Korea, was also associated with AAPC values in the first octile; in addition, a rising ASMR was noted in females from Nordic countries and the United States, as indicated by AAPC values within the final octile (0.33–3.36). As found in Fig. 1C, S1A & S1C, countries with AAPC in the first octile (< -2.84 for males and < -2.52 for females) for COPD-related ASMR largely overlapped with those whose AAPC in the first octile for CRD-related ASMR also occurred; a coincidence of countries was also discovered, where COPD-related ASMR in females showed positive AAPC values in the last octile (0.37–3.36), with CRD-related ASMR in females also exhibiting comparable positive AAPC values in the last octile. As discovered in Fig. 1D, S1B & S1D, the greatest decreases in pneumoconiosis-related ASMR, as reflected by AAPC values in the first octile (< -6.41 for males and < -4.62 for females), were concentrated in Western European nations, alongside the United States and Canada; conversely, regions with growing ASMR of pneumoconiosis, i.e. positive AAPC in the last octile (0.50–8.04 for males and 2.32–15.87), included the Mideast, North Africa, and Russia.

AAPCs in ASMR of occupational PMGF attributed-CRD from 1990–2021 for males (A), females (B), COPD (C), and pneumoconiosis (D), by countries. The map was generated using R version 4.3.3 software (Institute for Statistics & Mathematics, Vienna, Austria) (https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/base/old/4.3.3/).

Age-period-cohort effect of occupational PMGF-attributed CRD mortality

The global net drift in CRD mortality attributed to PMGF was − 2.52% (-2.62%, -2.42%), with males at -2.31% (-2.43%, -2.19%) and females at -3.18% (-3.32%, -3.05%), and local drifts for all age groups were below 0.05% (Fig. 2D, Table S4). The overall CRD death rate increased from 0.19/105 in the 25–30 age group to 109.42/105 in the 85–90 age group, followed by a gradual decline (Fig. 2A). A similar pattern was observed in males and females, with peak rates of 209.50/105 and 51.77/105, respectively (Fig. 2A). The total CRD mortality rate decreased between 1992 and 2021, with the period RR falling from 1.56 (1.53, 1.59) to 0.85 (0.84, 0.86) (Fig. 2B). The downward trend was more pronounced among females (1.80 (1.76, 1.85) to 0.84 (0.83, 0.86)) than males (1.48 (1.45, 1.51) to 0.84 (0.82, 0.85)) (Fig. 2B). From 1917 to 1992, cohort effects dropped monotonically, despite earlier fluctuations, and females had higher cohort RRs than males before 1947, with their RRs becoming lower afterward (Fig. 2C).

Net drifts in PMGF-attributed mortality were − 2.49% (-2.59%, -2.39%) for COPD and − 3.84% (-4.01%, -3.67%) for pneumoconiosis, with the corresponding local drifts for all age groups not exceeding 0.07% and − 2.22% (Fig. 3D, Table S4). The age-related trend in COPD death rate closely mirrored that of CRD, peaking at 109.01/105 in the 85–90 age group, whereas pneumoconiosis mortality remained nearly constant across all age groups (Fig. 3A). The death rates for both conditions exhibited similar age effects in males and females (Figures S2A & S5A). Between 1992 and 2021, the period RR for pneumoconiosis mortality (1.86 (1.78, 1.94) to 0.73 (0.70, 0.76)) declined more steeply than that for COPD mortality (1.56 (1.52, 1.59) to 0.85 (0.84, 0.86)) (Fig. 3B). While the cohort RR for pneumoconiosis mortality has experienced a continuous decline since 1897, a monotonic decrease in COPD mortality was not observed until 1917 (Fig. 3C). In males, the period and cohort effects for both diseases paralleled those seen in the general population; however, among females, a striking reversal was found, with the decline in COPD surpassing that of pneumoconiosis (Figures S2B, S2C, S5B & S5C).

Net drifts in CRD mortality attributable to PMGF among the five SDI regions ranged from − 4.30% (-4.47%, -4.13%) to -0.74% (-0.98%, -0.49%), with local drifts uniformly staying below 1.02% across all age groups (Fig. 4D, Table S4). The low-middle SDI region had the highest CRD mortality within all SDI regions for the age groups 25–30 to 90–95 (from 0.13/105 to 284.92/105), before dropping to second place in the 95 + age group (Fig. 4A). This was followed by the low SDI region, ranked second, where the CRD mortality rate increased monotonically, and the middle SDI region, ranked third, where it peaked in the 85–90 age group (Fig. 4A). In contrast, the age effect on CRD mortality in the high-middle and high SDI regions remained consistently lower than the global average (Fig. 4A). The age-related CRD mortality in males resembled that of the general population across SDI regions, while in females, it was nearly identical in the low and low-middle SDI regions for age groups under 85–90 (Figures S3A & S6A). From 1992 to 2021, the period RR for CRD mortality experienced the largest reduction in the high-middle SDI region (2.04 (1.98, 2.10) to 0.73 (0.72, 0.75)), with the smallest decrease observed in the low-middle SDI region (1.16 (1.10, 1.22) to 0.95 (0.91, 0.98)) (Fig. 4B). Similar period effects appeared in males across all SDI regions, however, the greatest and the mildest declines in females occurred in the middle SDI and high SDI regions, respectively (Figures S3B & S6B). The cohort RR for CRD mortality in areas with middle-to-high SDI decreased steadily after 1917, most sharply in the high-middle SDI region, while the declining trend in the low-middle and low SDI regions did not emerge until 1932 (Fig. 4C). Sex-specific cohort RR showed parallel trends, except for females, where the steepest decline in cohort effect occurred in the middle region (Figures S3C & S6C).

Net drifts in PMGF-related CRD mortality across seven GBD super regions varied from − 4.49% (-4.63%, -4.36%) to -0.93% (-1.24%, -0.61%), with corresponding local drifts not surpassing 1.23% across all age groups (Fig. 5D, Table S4). Age-specific CRD mortality in South Asia led all GBD regions, increasing linearly from 0.11/105 in the 25–30 age group to 378.51/105 in the 95 + age group, while Southeast Asia, East Asia, and Oceania followed closely, seeing mortality peak in the 90–95 age group (Fig. 5A). Except for the 95 + age group in Sub-Saharan Africa, age-related rates in the rest of the areas remained below the global level, particularly in Central Europe, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia where growth trends were extremely weak (Fig. 5A). Age effects followed the general trend in males, and exceeded the global average in Sub-Saharan Africa for all age groups in females (Figures S4A & S7A). Between 1992 and 2021, Southeast Asia, East Asia, and Oceania experienced the largest decrease in the period RR for CRD mortality, with Central Europe, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia coming in second (Fig. 5B). In contrast, the period effect showed the weakest attenuation in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia (Fig. 5B). For males, the period RR showed the most marked decline in Central Europe, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia, whereas for females, the smallest decrease was observed in high-income nations (Figures S4B & S7B). From 1907 on, the cohort effect for CRD mortality in Southeast Asia, East Asia, and Oceania declined most dramatically, with Central Europe, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia showing the second-largest reduction (Fig. 5C). In females, these two regions also showed the largest reduction in cohort RR, while for males, the cohort RR in both regions became nearly equal starting in 1917 (Figures S4C & S7C).

Discussion

Despite CRD being a class of irreversible and currently untreatable conditions, it is still possible to implement preventive measures to reduce the risk of developing the disease and slow its progression17. Occupational PMGF has increasingly been recognized as another significant risk factor for pulmonary conditions among workers, in addition to the well-established risk of smoking18. The GBD 2021 database indicates objective gender and regional differences in CRD mortality attributable to occupational PMGF exposure. Our study not only highlighted these disparities but also included an analysis of age, period, and cohort effects, thereby enhancing the reliability and persuasiveness of the results. We aim to further investigate the underlying mechanisms of gender and location-based disparities in respiratory disease mortality resulting from workplace PMGF exposure, with the goal of providing more targeted guidance for the revision and implementation of future occupational health strategies.

Our observations over the past 32 years indicate that occupational PMGF-related CRD death rates have remained higher in men, reflecting the male dominance in traditional industries that expose workers to elevated levels of particulate matter and aerosols. This trend aligns with the overall higher mortality for all types of CRD in men during the same period19. We observe that despite a general decline in PMGF-attributed CRD mortality, women exhibited a more marked decline, particularly in the improvement of COPD mortality, which was notably greater than that in men. Previous studies have shown that when exposed to the same amount of tobacco as men, women exhibited heightened susceptibility to COPD; conversely, they were expected to derive greater benefits from COPD intervention20. We hypothesize that similar mechanisms may be involved in the onset of COPD induced by occupational dust. Current APC analysis further emphasizes a growing gender gap, where men’s age-specific death rates rose significantly with age, while women showed a steadily intensifying decline in mortality between the recent and early birth cohorts. Our research highlights the importance of implementing gender-sensitive occupational health policies, notably in majority-male workplaces in LIMICs, where considering gender differences can challenge stereotypes held by occupational health professionals and ensure equal health protection for both genders.

The study indicates that the effectiveness of controlling occupational pneumoconiosis from particulate matter in male workers has been notably better than for COPD, a result of the sustained efforts by industrial hygiene practitioners worldwide. The introduction of the Global Program for the Elimination of Silicosis in 1995 has led to a remarkable decrease in pneumoconiosis deaths attributed to various causes21. However, as with previous findings, the notably rapid increase in pneumoconiosis-related deaths in the Middle East and North Africa remained striking, suggesting the necessity for oriented occupational health legislation and accountability22. In comparison, COPD control remains far from optimal. Despite the Global Initiative for COPD (GOLD) stressing the importance of early screening, its widespread adoption in many LMICs is hindered by poor healthcare accessibility, low public awareness, and limited financial resources23. Although early screening has successfully reduced the mortality of occupational dust-related COPD in Western Pacific countries, it has failed to curb the rising trends among women in the United States and Nordic countries, as our study reveals. The growth in the United States figures may be associated with a rise in COPD deaths among African American women24. Meanwhile, the COPD scenario in the Nordic countries is alarming, with mortality rising annually, as COPD is often misclassified as a complication, leading to an underestimation of the true death rate25. The growing occupational health burden among women in the United States and Nordic countries points to the fact that, despite the early adoption of strict occupational safety measures, prolonged exposure to even minimal doses of pollutants may still result in substantial cumulative effects, presenting a new challenge to the existing industrial hygiene limits in economically developed regions.

From the APC model, we observe an age effect on PMGF-attributed CRD mortality, marked by a steady rise from the 25–30 to the 85–90 age group. This age-dependent trend may be explained by the decline in pulmonary tissue elasticity and the weakening of airway immune defenses, both of which contribute to symptom deterioration in the elderly26. The sudden decrease in CRD deaths in the 90 + age group may reflect the presence of other competing causes of death. The age effect in South Asia’s low and low-middle SDI regions, characterized by a clear upward trajectory, far ahead of other areas, underscores the challenges posed by the gradual aging of the local population, which will inevitably worsen the burden on already limited and unevenly distributed healthcare resources in managing occupational respiratory diseases27. The growing age-specific occupational health burden emphasizes the need to prioritize screening for middle-aged and older individuals as a high-risk group, and underscores the importance of more timely and personalized occupational health interventions for this population.

In South Asia, the progressive shift of CRD mortality attributable to PMGF toward the elderly group, notably in underdeveloped countries, underscores the necessity for local occupational health administrations to enhance their focus on the health of the retired population. What’s more, South Asian women have experienced a modest increase in PMGF-related CRD deaths over the past 32 years, with positive annual average changes in India and Pakistan, possibly shedding light on the critical shortage of equitable healthcare opportunities available to local women28. As is widely recognized, gender biases, entrenched in South Asian traditional culture, lead to a prioritization of men’s health needs. Coupled with women’s generally lower educational levels, these cognitive constraints severely limit their capacity to obtain external information29. Therefore, it can be anticipated that improving respiratory health among women in South Asia will require not only financial investment and personnel training but also the initiation of policy guidance, the promotion of cultural awareness to eradicate gender biases, and the establishment of legally binding regulations.

Regarding Sub-Saharan Africa, the current study observes an age effect, mildly higher than the global average, but only in women’s PMDF-related CRD death. This finding appears inconsistent with the severe challenges the region currently faces in controlling long-term pulmonary diseases. According to existing literature, there has been a lack of sufficient awareness and evaluation of the true status of COPD in Sub-Saharan Africa, which may lead to a substantial underestimation of the actual data30. The SDI often reflects the healthcare standard, resulting in a typically negative correlation with the occurrence of CRD. However, our analysis reveals that in low-SDI regions, largely represented by Sub-Saharan Africa, the age-related mortality rate did not rank first, as originally anticipated. Furthermore, over the past 32 years, only Kenya and Zimbabwe have experienced a positive annual change in mortality, while the remaining countries have seen a decline in mortality. These flawed survey findings, though only reflecting the tip of the iceberg in chronic disease control efforts in the sub-Sahara, also suggest that the region is facing a critical phase in its healthcare reform process. Despite local health policies and resources having historically been focused on addressing infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis, chronic non-communicable diseases are set to emerge as the leading cause of death in the coming years31. Given the economic burden arising from the dual healthcare dilemma in the sub-Sahara, relying solely on international donations and loans is inadequate to tackle the new challenges. Hence, it is crucial for local policymakers to establish a fair and efficient system for allocating healthcare expenditure to better confront the current circumstances32. Meanwhile, occupational health strategies in the sub-Saharan region should gradually move away from merely adopting generic standards set by international organizations and instead focus on formulating more localized policies that are better aligned with the region’s specific occupational health realities.

Southeast Asia, East Asia, and Oceania have witnessed the most rapid descent in CRD mortality due to occupational dust over the past few decades, as demonstrated by our research results, with the APC model also confirming that both its period and cohort effects have declined to the greatest extent. The reduction in period effects is indicative of the remarkable advancements in early screening technologies across the Asia-Pacific region, including lifelong screening for dust-exposed workers and targeted screening for high-risk populations of obstructive lung diseases, complemented by long-term and systematic care and treatment for patients, yielding promising results33. The decline in cohort effects, in another sense, reflects the noticeable improvements in working conditions for those born more recently, particularly through the regular and stringent monitoring of pollutants like aerosol and particulate matter in the workplace, thereby diminishing their potential harm to workers’ respiratory health at the source. Despite this, the situation of occupational respiratory disease control in Southeast Asia, East Asia, and Oceania is still far from optimistic, with its second-highest age-related death rate which sends numerous critical warnings. As China and Indonesia, two traditionally large population countries, transition into an aging society, the costs and difficulties in managing CRD are inevitably increasing34. Consequently, local chronic disease prevention programs should be prioritized in key areas to maximize the efficiency of public health resources. Given the cumulative effects and delayed health repercussions of occupational PMGF exposure, the establishment of systematic, long-term, and even lifelong occupational health monitoring for the large workforce in this area, especially in densely populated countries, is necessary.

We also note a clear reduction in the absolute number of CRD deaths due to PMGF exposure in Central Europe, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia over the past 32 years. The APC model further indicates that the age-dependent mortality in this region has shown minimal growth, with both period and cohort effects experiencing some of the largest declines. Social development in the region is highly heterogeneous. Although Central European countries such as Poland and Hungary have progressively aligned their healthcare systems with Western Europe since joining the European Union, many Central Asian nations continue to struggle with legacy issues stemming from historical upheavals, resulting in outdated medical infrastructure and a shortage of healthcare professionals35. The high-middle SDI regions, including most Central European countries, have observed the sharpest decrease in period and cohort effects on mortality, outpacing other SDI regions. This trend, as reported in our analysis, underscores the far-reaching impact of thirty years of social transformation on chronic disease control. Thus, this seemingly “favorable” number, overall, is likely the outcome of an unfair averaging method that incorporates Central European data. More in-depth analyses at the country level should be performed in the future to enhance the precision and rigor of the findings. Because of the considerable inequalities in healthcare facilities and professionals within the region, occupational chronic disease management strategies should focus on enhancing cross-nation collaboration and experience sharing, while providing additional technical support and financial assistance to relatively resource-limited countries.

Before delineating our conclusions, it’s crucial to address the inevitable shortcomings present in our current study. First of all, given that our data utilized was derived from GBD 2021, a database with multiple avenues, the heterogeneity in data quality as well as the potential underreporting have influenced the robustness of our findings. Secondly, variability in inherent diagnostic standards and actual diagnostic results across regions, with some cases erroneously attributed to risk factors other than occupational PMGF, would potentially bring out an underestimation of the real CRD burden associated with this specific hazard. Last but not least, the APC model, while meticulously evaluating the age-period-cohort effect, omitted the inclusion of other possible risk factors that might influence mortality.

Conclusion

Our current study has, for the first time, analyzed the effects of age, period, and cohort on the long-term trends of CRD mortality attributable to occupational PMGF exposure, with comparisons across different gender, regional, and disease subgroups. We have substantial global improvements over the past 32 years, particularly among women, pneumoconiosis patients, and Asia-Pacific nations with medium-to-high development levels, in effectively addressing industrial PMGF pollution-related CRD. However, ongoing challenges remain, notably for sub-Saharan individuals, South Asian women, some pneumoconiosis cases in the Middle East and North Africa, and certain female COPD patients in high-income countries, who require enhanced public health policy support and a greater allocation of healthcare resources.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the Global Burden of Disease 2021 datasets (https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/).

Abbreviations

- AAPC:

-

average annual percentage change

- APC:

-

age-period-cohort

- ASMR:

-

age-standardized mortality rate

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CRD:

-

Chronic respiratory disease

- DALY:

-

disability-adjusted life year

- GARD:

-

Global Alliance against Chronic Respiratory Diseases

- GBD:

-

Global Burden of Disease

- GOLD:

-

Global Initiative for COPD

- ICD-10:

-

Tenth Edition of International Classification of Diseases

- LMICs:

-

low- and middle-income countries

- PMGF:

-

particulate matter, gases, and fumes

- RR:

-

rate ratio

- SDG:

-

Sustainable Development Goal

- SDI:

-

socio-demographic index

- UI:

-

uncertainty interval

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Labaki, W. W. & Han, M. K. Chronic respiratory diseases: a global view. Lancet Respiratory Med. 8 (6), 531–533 (2020).

Meghji, J., Jayasooriya, S., Khoo, E. M., Mulupi, S. & Mortimer, K. Chronic respiratory disease in low-income and middle-income countries: from challenges to solutions. J. Pan Afr. Thorac. Soc. 3 (2), 92–97 (2022).

Momtazmanesh, S. et al. Global burden of chronic respiratory diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: an update from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. EClinicalMedicine 59. (2023).

Assembly, U. G. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. In.; 2015. (2015).

Organization, W. H. Global surveillance, prevention and control of chronic respiratory diseases: a comprehensive approach. In: Global surveillance, prevention and control of chronic respiratory diseases: a comprehensive approach. edn.; : vii. 146-vii. 146. (2007).

Higgins, I. T. The epidemiology of chronic respiratory disease. Prev. Med. 2 (1), 14–33 (1973).

Lange, P., Ahmed, E., Lahmar, Z. M., Martinez, F. J. & Bourdin, A. Natural history and mechanisms of COPD. Respirology 26 (4), 298–321 (2021).

Castranova, V. & Vallyathan, V. Silicosis and coal workers’ pneumoconiosis. Environ. Health Perspect. 108 (suppl 4), 675–684 (2000).

Su, X., Gu, H., Li, F., Shi, D. & Wang, Z. Global, Regional, and National Burden of COPD Attributable to Occupational Particulate Matter, gases, and fumes, 1990–2019: findings from the global burden of Disease Study 2019. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2023:2971–2983 .

Collaborators, G. U. B. D. The burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors by state in the USA, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet.

Schneider, A. et al. Are ICD-10 codes appropriate for performance assessment in asthma and COPD in general practice? Results of a cross sectional observational study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 5, 1–6 (2005).

Swift, M. B. A simulation study comparing methods for calculating confidence intervals for directly standardized rates. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 54 (4), 1103–1108 (2010).

Downs, S. M., Ahmed, S., Warne, T., Fanzo, J. & Loucks, K. The global food environment transition based on the socio-demographic index. Global Food Secur. 33, 100632 (2022).

Murray, C. J. et al. GBD 2010: design, definitions, and metrics. Lancet 380 (9859), 2063–2066 (2012).

Clegg, L. X., Hankey, B. F., Tiwari, R., Feuer, E. J. & Edwards, B. K. Estimating average annual per cent change in trend analysis. Stat. Med. 28 (29), 3670–3682 (2009).

Bell, A. Age period cohort analysis: a review of what we should and shouldn’t do. Ann. Hum. Biol. 47 (2), 208–217 (2020).

Burney, P., Jarvis, D. & Perez-Padilla, R. The global burden of chronic respiratory disease in adults. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 19 (1), 10–20 (2015).

Poole, J. A., Zamora-Sifuentes, J. L., De las Vecillas, L. & Quirce, S. Respiratory diseases associated with organic dust exposure. J. Allergy Clin. Immunology: Pract. 12 (8), 1960–1971 (2024).

Li, X., Cao, X., Guo, M., Xie, M. & Liu, X. Trends and risk factors of mortality and disability adjusted life years for chronic respiratory diseases from 1990 to 2017: systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. bmj 368. (2020).

Aryal, S., Diaz-Guzman, E. & Mannino, D. M. Influence of sex on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease risk and treatment outcomes. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2014:1145–1154 .

Min, L., Mao, Y. & Lai, H. Burden of silica-attributed pneumoconiosis and tracheal, bronchus & lung cancer for global and countries in the national program for the elimination of silicosis, 1990–2019: a comparative study. BMC Public. Health. 24 (1), 571 (2024).

Wang, Z. et al. Current status, trends, and predictions in the burden of coal worker’s pneumoconiosis in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019. Heliyon 10(19). (2024).

Alupo, P. et al. Overcoming challenges of managing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in low-and middle-income countries. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2024:1–10 .

Zarrabian, B. & Mirsaeidi, M. A trend analysis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease mortality in the United States by race and sex. Annals Am. Thorac. Soc. 18 (7), 1138–1146 (2021).

Gulsvik, A., Boman, G., Dahl, R., Gislason, T. & Nieminen, M. The burden of obstructive lung disease in the nordic countries. Respir. Med. 100, S2–S9 (2006).

Holtzman, M. J., Byers, D. E., Alexander-Brett, J. & Wang, X. The role of airway epithelial cells and innate immune cells in chronic respiratory disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14 (10), 686–698 (2014).

Chand, M. Aging in South Asia: challenges and opportunities. South. Asian J. Bus. Stud. 7 (2), 189–206 (2018).

Jafree, S. R., Zakar, R. & Anwar, S. Women’s role in decision-making for health care in South Asia. Sociol. South. Asian Women’s Health 2020:55–78 .

Mahmood, A. Role of education in human development: a study of south Asian countries. Bus. Rev. 7 (2), 130–142 (2012).

Van Gemert, F., van der Molen, T., Jones, R. & Chavannes, N. The impact of asthma and COPD in sub-saharan Africa. Prim. Care Respiratory J. 20 (3), 240–248 (2011).

Gouda, H. N. et al. Burden of non-communicable diseases in sub-saharan Africa, 1990–2017: results from the global burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Global Health. 7 (10), e1375–e1387 (2019).

Novignon, J., Olakojo, S. A. & Nonvignon, J. The effects of public and private health care expenditure on health status in sub-saharan Africa: new evidence from panel data analysis. Health Econ. Rev. 2, 1–8 (2012).

Agarwal, D. et al. Predictors for detecting chronic respiratory diseases in community surveys: a pilot cross-sectional survey in four South and South East Asian low-and middle-income countries. J. Global Health 11. (2021).

Shilian, H., Jing, W., Cui, C. & Xinchun, W. Analysis of epidemiological trends in chronic diseases of Chinese residents. In., vol. 3: Wiley Online Library; : 226–233. (2020).

Adambekov, S., Kaiyrlykyzy, A., Igissinov, N. & Linkov, F. Health challenges in Kazakhstan and central Asia. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 70 (1), 104–108 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We are sincerely grateful to all the participants for their help. We want to express our gratitude to the GBD Collaborators for sharing data in public and permitting relevant analysis. We also acknowledge Doctor S. L. for his help with R code programming.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Jiangsu Province Innovation & Entrepreneurship (No. 337090129) and Yangzhou City “Golden Phoenix in Green Yangzhou” Project (No. 137012416).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C. Xu and H. Lai contributed to the study design and essay writing. Y. Zhou contributed to the data collection and interpretation. H. Lai contributed to the statistical analysis and graph generation. All the authors have approved the manuscript submission to the Scientific Reports.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Y., Lai, H. & Xu, C. Global trends and age-period-cohort effects of chronic respiratory disease mortality attributed to industrial gaseous pollutants from 1990 to 2021. Sci Rep 15, 11924 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90406-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90406-4