Abstract

The manta ray foraging optimization (MRFO) algorithm has gained widespread application in engineering problems due to its notable performance and low computational cost. However, the algorithm is prone to getting trapped in local optima and struggles to effectively balance exploration and exploitation, primarily due to the use of fixed parameters and its somersault foraging mechanism, which focuses solely on the current best solution. To address these shortcomings, we propose an improved version called hierarchical guided manta ray foraging optimization (HGMRFO). In this version, the fixed parameters are replaced with an adaptive somersault factor, which helps balance exploration and exploitation during the evolutionary process. A novel hierarchical guidance mechanism is introduced in the somersault foraging strategy. Starting from the population structure, the mechanism guides the search direction of the population individuals through hierarchical interactions. To validate the effectiveness of HGMRFO, we compared it with seven state-of-the-art algorithms on 29 IEEE CEC2017 benchmark functions, achieving an average win rate of 73.15%. On 22 IEEE CEC2011 real-world optimization problems, HGMRFO obtained the most optimal solutions. Additionally, we analyzed the optimal parameter configurations, the impact of hierarchical interactions, and the computational complexity of the proposed method. Finally, when solving the parameter estimation problems for six multimodal photovoltaic models, HGMRFO outperformed other competing methods with a success rate of 97.62%, highlighting its superior performance in the photovoltaic field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metaheuristic optimization algorithms have emerged as a prominent class of optimization techniques capable of addressing complex, nonlinear, and high-dimensional problems1,2. Unlike classical optimization methods, metaheuristics do not require derivative information and are more flexible in handling a wide range of objective functions3. By drawing inspiration from natural and physical processes, these algorithms effectively explore and exploit solution spaces. Prominent examples of metaheuristic algorithms include genetic algorithms (GA)4, particle swarm optimization (PSO)5, ant colony optimization (ACO)6, and gravitational search algorithm (GSA)7. There are also the latest algorithms, such as draco lizard optimizer8, eurasian lynx optimizer9, and artificial meerkat algorithm10.

One critical feature of many advanced metaheuristic methods is their hierarchical structure, which organizes the population into different layers or subgroups11. The hierarchical structure facilitates efficient information exchange and diversity preservation by promoting interactions between various segments of the population12. This layered approach is crucial for preventing premature convergence and ensuring comprehensive exploration of the solution space. By structuring the population hierarchically, metaheuristic algorithms can effectively balance the dual demands of exploration (searching new regions) and exploitation (intensifying search around promising solutions).

Manta ray foraging optimization (MRFO)13 has emerged as a powerful technique inspired by the unique foraging behaviors of manta rays, including chain foraging, cyclone foraging, and somersault foraging strategies. These strategies enable manta rays to adapt dynamically to changing environmental conditions, allowing MRFO to maintain a balance between exploration and exploitation. The original MRFO has shown significant effectiveness in addressing a variety of practical optimization challenges. Nevertheless, as is common with many metaheuristic approaches, MRFO faces challenges such as premature convergence and reduced population diversity, which limit its capacity to reliably discover the global optimal solution. Addressing these challenges requires further enhancements to ensure effective exploration of the solution space and to prevent convergence to suboptimal solutions.

In recent years, numerous advancements have been made in the MRFO algorithm, aimed at overcoming its limitations and enhancing its performance. Researchers have focused on strategies to mitigate premature convergence and enhance population diversity. For instance, adaptive control mechanisms for parameters have been proposed, allowing the algorithm to dynamically adjust based on the state of the search process14,15. Hybrid approaches that integrate MRFO with other metaheuristic algorithms, such as GA and PSO, have also been introduced to enhance global exploration capabilities and improve solution quality16,17.

Another line of research has focused on developing novel selection strategies to diversify the population and maintain a robust search process. These strategies often involve elite preservation, and opposition-based learning techniques to help balance exploration and exploitation12,18. Elite preservation ensures that the best solutions are retained across generations, opposition-based learning has been demonstrated to be particularly effective in enhancing the convergence rate of MRFO by periodically reinitializing certain members of the population with more promising candidates19,20. Additionally, the incorporation of chaotic maps and Levy flights has been demonstrated to further enhance MRFO’s search efficiency, minimizing the probability of the algorithm getting trapped in local optima21,22. Chaotic maps help in better initial population distribution, which is crucial for global exploration, whereas Levy flights provide a mechanism for making larger, more diverse jumps in the search space, especially useful for avoiding local optima.

Moreover, multi-objective extensions of MRFO have been introduced to address problems involving multiple conflicting objectives. These multi-objective versions utilize Pareto-based selection mechanisms and crowding distance measures to maintain a diverse set of solutions while achieving an effective trade-off among objectives23,24. Recently, more advanced multi-objective methods such as inertia weight decreasing approaches and adaptive trade-off models have been incorporated to improve the flexibility and robustness of multi-objective MRFO25,26. These improvements allow MRFO to handle practical, real-world scenarios where multiple criteria must be optimized simultaneously, providing decision-makers with a set of Pareto-optimal solutions.

Another noteworthy advancement is the incorporation of memory-based strategies within MRFO, where successful solutions from previous iterations are stored and used to guide future search efforts15,27. Such strategies allow the algorithm to learn from historical data, which significantly improves the efficiency of the search, especially in dynamic environments. Furthermore, adaptive step-size mechanisms have been developed to refine the local search capabilities of MRFO. By adaptively adjusting the search step size based on the improvement rate in the fitness value, these methods help strike a better balance between exploration and exploitation21,28.

MRFO also has been effectively integrated with advanced machine learning methodologies, leading to significant advancements in feature selection, hyperparameter optimization, and classification tasks, particularly in medical and biomedical applications. MRFO has been employed to optimize support vector machines (SVM) and convolutional neural networks (CNN), resulting in enhanced classification accuracy and reduced data dimensionality29. MRFO has been hybridized with CNNs for brain tumor detection, demonstrating superior performance compared to traditional optimization methods30. Collectively, MRFO substantially enhances the accuracy, robustness, and generalization capabilities of machine learning models in the medical and biomedical domains, providing a powerful tool for addressing complex classification and feature selection challenges.

Overall, these improvements have made MRFO a more versatile and powerful optimization tool capable of solving a broader range of complex problems. The advancements not only extend the applicability of MRFO to diverse fields such as engineering design, energy systems, and biomedicine but also enhance its effectiveness in handling practical challenges characterized by multiple objectives, dynamic environments, and computational constraints.

In recent years, numerous parameter estimation methods for solar photovoltaic models have emerged. In31, experimental comparisons between hybrid methods and metaheuristic methods for photovoltaic parameter estimation revealed that hybrid methods provide more accurate parameter estimation. In32, the trust-region dogleg (TRD) and trust-region reflective (TRR) algorithms were employed to estimate three unknown parameters in the solar photovoltaic model, while the remaining two parameters were determined using an analytical approach. In33, a hybrid approach combining grey wolf optimization (GWO) and analytical methods achieved promising results in photovoltaic parameter estimation. In34, a comparative analysis of existing photovoltaic parameter estimation techniques revealed that hybrid-based parameter estimation methods achieve more accurate photovoltaic characteristics. In35, a multi-hybrid evolutionary algorithm based on the flower pollination algorithm (FPA), grey wolf optimizer (GWO), and differential evolution (DE) algorithm was used for precise and effective parameter estimation of photovoltaic systems. In36, a new algorithm, the pelican optimization algorithm (POA), was proposed for the optimal parameter estimation of photovoltaic systems, achieving promising results. In37, reinforcement learning and nonlinear hunting strategies were integrated into the golden jackal optimizer, achieving promising results in photovoltaic parameter estimation, making it a reliable tool for this task. In38, a multi-strategy (self-adaptive weighting mechanism, chaotic elite learning approach, and experience-based learning method) tree seed algorithm was used for photovoltaic model parameter estimation, achieving successful results. In39, the study found that the hybrid approach combining the linear slope method and GWO yields photovoltaic parameters that are closer to the real characteristics. In40, a nonlinear least squares (NLS) objective function was constructed using manufacturer datasheet information, and particle swarm optimization (PSO) was employed to estimate the unknown parameters of the photovoltaic model, achieving higher accuracy.

Within these study, we introduce the hierarchical guided manta ray foraging optimization (HGMRFO), which incorporates an adaptive somersault factor to replace the original fixed parameter \(S\), and a hierarchical guidance search mechanism to replace the sole reliance on the current best individual during somersault foraging. These modifications enable effective directionality in individual searches and facilitate an improved equilibrium between exploration and exploitation. During the experimental phase, the optimal parameter configuration for HGMRFO was systematically determined, and the effectiveness of the complete hierarchical structure was demonstrated. Comparative analyses were conducted using the IEEE CEC2017 benchmark and IEEE CEC2011 real-world optimization problem sets, thereby validating the superior performance and practicality of HGMRFO. Furthermore, the proposed algorithm was applied to parameter estimation in solar photovoltaic models, where it exhibited promising real-world applicability and effectiveness.

The main contributions of this research are as follows:

1. Introduction of the hierarchical guidance mechanism: This paper innovatively alters the population structure, guiding individuals toward the global optimal solution through layered interactions. This approach overcomes the limitations of many existing algorithms that focus solely on searching around the current best solution. On the CEC2017 benchmark functions, the algorithm achieved an average win rate of 73.15%, and it obtained the most optimal solutions on the CEC2011 real-world optimization problems. These results effectively demonstrate that the mechanism significantly enhances the algorithm’s global search capability in complex optimization problems.

2. Adaptive parameter adjustment strategy: An adaptive parameter tuning mechanism was implemented to achieve a dynamic balance between the exploration and exploitation stages of the search process. This strategy alleviates premature convergence issues caused by fixed parameter settings. The convergence curves obtained across various dimensional functions clearly show that this strategy significantly improves the algorithm’s robustness and effective convergence.

3. Application in photovoltaic model parameter estimation: The improved algorithm was applied to parameter estimation for six photovoltaic (PV) models, achieving a 97.62% success rate. This not only verifies the algorithm’s comprehensive performance in PV modeling but also demonstrates its potential practical utility and broad applicability in the renewable energy field.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section “Related work” provides an overview of related work, including a detailed introduction to the fundamental MRFO and classifications of population structures. Section “Hierarchical guided manta ray foraging optimization (HGMRFO)” identifies the limitations of MRFO and subsequently proposes the HGMRFO as an enhancement. Section “Experiments and analysis” presents the experimental and analytical aspects of the study, where the parameter sensitivity and hierarchical interactions of HGMRFO are comprehensively analyzed, and comparative experiments with state-of-the-art algorithms are conducted on benchmark functions and real-world optimization problems. Moreover, the practical applicability of HGMRFO is validated through its application to parameter estimation in photovoltaic models. Section “Conclusions” concludes the paper by summarizing key findings and outlining potential directions for future research.

Related work

Basic MRFO

MRFO algorithm is inspired by the unique foraging behavior of manta rays and employs three distinct mechanisms-chain foraging, cyclone foraging, and somersault foraging-to effectively drive the optimization process. These mechanisms collectively simulate the exploratory and exploitative capabilities of the swarm, ultimately enhancing optimization performance.

In the MRFO framework, a population of \(N\) manta ray individuals is represented as \(X_{i}=\left( x_{i}^{1}, x_{i}^{2}, \ldots , x_{i}^{d} \right)\), where \(i \in \{1,2, \ldots , N\}\) and \(x_{i}^d\) denotes the position of the \(i\)th individual in the \(d\)th dimension. Each individual employs different foraging behaviors to navigate the search space, described in detail below.

The chain foraging mechanism replicates the behavior of manta rays moving in a coordinated chain formation, in which each individual follows the one ahead. The position of each manta ray is influenced by both the current best solution and the individual directly in front of it, which enhances both exploration and convergence toward the optimal solution. The update equation for chain foraging is formulated as:

where, \(X_{\text {best}}=\left( x_{\text {best}}^{1}, x_{\text {best}}^{2}, \ldots , x_{\text {best}}^{d}\right)\) represents the current best individual, \(x_{\text {best}}^{d}(t)\) denotes the position of the best individual in the \(d\)th dimension at time \(t\). \(r\) is a random number within the range \([0, 1]\). The coefficient \(\alpha\) is introduced to adjust the weight of the search direction, enhancing the effectiveness of the foraging behavior.

In the cyclone foraging phase, manta rays exhibit a spiraling behavior around the current best solution, which enhances their ability to perform local search. Unlike chain foraging, this behavior aims to increase the exploration capability of the population by generating a swirling motion around the optimal solution. The position update in cyclone foraging is modeled as:

where \(\beta\) is a dynamic coefficient dependent on the random number \(r_1 \in [0,1]\), and \(T\) represents the maximum number of iterations. The cyclone foraging mechanism includes an additional feature that selects a random individual as a reference point to preserve variability and mitigate the likelihood of getting trapped in local optima, formulated as:

where \(x_{\text {rand}}^{d}\) denotes the position of a randomly selected individual, and \(L b^{d}\), \(U b^{d}\) represent the lower and upper bounds for dimension \(d\). This mechanism ensures improved solution diversity, effectively preventing premature convergence.

The final strategy, somersault foraging, simulates the somersault movements of manta rays around the optimal solution. This behavior aims to balance exploration and exploitation by allowing individuals to adjust their positions with respect to the best-known solution, thereby improving convergence accuracy. The somersault foraging update is expressed as:

where \(S\) is a constant parameter controlling the somersault magnitude, and \(r_2, r_3 \in [0, 1]\) are random numbers. This mechanism progressively reduces the movement range of each individual as iterations proceed, thereby enhancing the precision of the solution search.

The overall workflow of MRFO is depicted in Fig. 1. Initially, either chain or cyclone foraging is selected based on a random criterion. During the cyclone foraging phase, the decision of whether to use the current best solution or a random reference is made based on the ratio \(t/T\), thereby balancing global and local exploration. Ultimately, each individual performs somersault foraging to refine its position, ensuring steady convergence to the optimal solution. This coordinated use of chain, cyclone, and somersault foraging effectively balances the exploration and exploitation capabilities of the algorithm, thereby enhancing both its robustness and convergence efficiency.

Population structure

Population structure plays a crucial role in optimization algorithms, involving the allocation, organization, and management of individuals to identify superior solutions. The design of population structure significantly impacts the exchange of information among individuals and the maintenance of population diversity, both of which are critical for effective exploration and exploitation within the search space. Common population structures are generally classified into three categories:

-

(1)

Panmictic structure: The panmictic structure is the most fundamental and widely adopted population configuration41. In this structure, individuals interact with each other by randomly selecting partners, which expedites the dissemination of information across the population. However, frequent and random interactions often result in insufficient population diversity, leading to premature convergence and hindering comprehensive exploration of the solution space.

-

(2)

Neighborhood structures: To address the premature convergence problem inherent in panmictic structures, neighborhood-based configurations have been developed, leveraging both fitness values and spatial topology to enhance information exchange42,43. By promoting diversified neighborhood interactions, these structures facilitate evolutionary processes and enhance algorithmic performance. Neighborhood structures are predominantly categorized into cellular structures and distributed structures44,45.

In cellular structures, individuals are organized into a grid, interacting exclusively with their immediate neighbors, which may partially overlap. This localized interaction helps maintain population diversity and mitigate premature convergence42. For instance, Dorronsoro and Alba introduced a cellular genetic algorithm that demonstrated the effective diffusion of solutions throughout the population45. Cellular structures have also been employed to enhance differential evolution variants46 and address dynamic optimization problems by integrating mechanisms such as clonal selection47. In the context of differential evolution, cellular direction information has been utilized to improve exploration and convergence rates through a combined approach48.

In distributed structures, the population is partitioned into multiple subpopulations that evolve independently while sharing information via migration strategies. Each subpopulation searches the solution space in its specific region, and migration strategies facilitate effective information exchange among different subpopulations49. Through this migration mechanism, distributed structures effectively expand the exploration range and further enhance population diversity. For example, a PSO divided the population into two types of swarms-one composed of elite individuals and the other used for exploring alternative regions of the solution space50. In another study, a multicultural migration strategy was proposed to further increase population diversity in distributed differential evolution51.

The hierarchical structure is a specific type of distributed configuration that allocates individuals across multiple layers, each serving distinct purposes, while enabling dynamic information exchange among the layers52. This stratification facilitates the evolution of subsequent generations by promoting inter-layer communication. For example, in dynamic hierarchical particle swarm optimization, particles can move vertically within the hierarchy, allowing the most promising individuals to ascend and optimize the population at multiple levels53. Hierarchical designs, such as the multi-layered GSA, significantly improve the balance between exploration and exploitation through hierarchical interactions11. In the context of MRFO, Tang et al. introduced an update mechanism that incorporates weighted fitness-distance balance selection, further enhancing diversity12. Similarly, Wang et al. proposed a deep-layered differential evolution approach comprising four distinct layers, effectively balancing diversity, exploration, and exploitation54.

3) Structures with small-world and scale-free attributes: In addition to panmictic and neighborhood structures, some population configurations exhibit small-world and scale-free properties. The Watts-Strogatz and Barabási-Albert models are commonly employed to construct small-world networks and scale-free topologies, respectively55. Small-world networks uniquely blend features of random graphs and regular lattices, significantly improving the balance between exploration and exploitation during the search process41. For example, Zhang et al. used scale-free networks to adapt the PSO population structure, endowing it with scale-free properties that significantly improved population diversity and algorithm performance56. In another study, Yu et al. leveraged neighborhood information from scale-free networks to refine the mutation operator in differential evolution, thus improving the algorithm’s capacity for both exploration and exploitation of the search space57.

In conclusion, population structure is fundamental to the success of optimization algorithms. Through careful design of topological structures and strategic interactions among individuals, population structures can achieve an effective balance between exploration and exploitation, significantly improving both the efficiency and quality of solution searches58,59,60. Different population structures offer unique advantages in terms of information exchange and diversity maintenance, making them suitable for a wide range of optimization problems.

Hierarchical guided manta ray foraging optimization (HGMRFO)

Issues of MRFO

The somersault foraging mechanism in the MRFO algorithm, which aims to replicate the intricate movement behavior of manta rays during their foraging activities, presents notable limitations in its current form. These limitations are evident in the following update equation:

The main limitations are:

-

(a)

Fixed parameter \(S\): The parameter \(S\), which controls the magnitude of the somersault movement, is kept constant throughout the optimization process. This static setting imposes significant constraints on the adaptability of the algorithm’s search behavior. During the initial optimization stages, a larger value of \(S\) would be beneficial for promoting global exploration and preventing premature convergence to local optima. Conversely, in the latter stages, a smaller value would enhance the ability to fine-tune the search around promising regions. By keeping \(S\) fixed, MRFO struggles to dynamically balance exploration and exploitation, leading to a less efficient convergence rate and ultimately compromising the quality of the obtained solution.

-

(b)

Limited exploration mode centered on the current best individual: The somersault foraging mechanism directs all individuals to perform movements around the current best solution, \(x_{\text {best}}\). While this approach aims to accelerate convergence by intensifying focus on promising areas of the solution space, it inherently suffers from a significant drawback: it considerably reduces population diversity over time. As individuals concentrate around \(x_{\text {best}}\), the search space becomes increasingly constrained, leading to rapid convergence to a localized region. This reduction in diversity weakens the algorithm’s capacity for thorough exploration of the solution space, increasing the risk of MRFO getting stuck in local optima. This problem becomes especially evident in complex, multimodal landscapes, where the presence of numerous local optima makes identifying the global optimum more challenging.

In conclusion, the somersault foraging mechanism’s dependence on a fixed parameter \(S\) and its singular focus on the current best individual substantially limit MRFO’s capacity to balance exploration and exploitation effectively. These limitations heighten the risk of premature convergence and undermine the robustness of the search process. To address these issues, enhancements could include dynamically adapting the parameter \(S\) based on the current state of the search, as well as introducing alternative movement strategies that foster greater exploration diversity. Such improvements are anticipated to bolster MRFO’s adaptability, enhance convergence efficiency, and improve overall solution quality.

Proposed HGMRFO

Adaptive somersault factor (\(S\))

In the MRFO, the somersault factor \(S\) is generally a constant value that determines the range for somersault searches centered around the current best solution. However, a fixed value for \(S\) presents significant limitations at different optimization stages: a larger \(S\) value is beneficial in the early stages to enhance exploration and discover more unknown regions, while a smaller \(S\) is more suitable for fine-tuning solutions during the local exploitation phase. Therefore, a fixed \(S\) value lacks the flexibility needed to adapt to the dynamic requirements of various optimization phases, which ultimately restricts the effectiveness of global exploration and local exploitation.

To address this limitation, an adaptive somersault factor can be introduced to replace the fixed constant \(S\), allowing it to be dynamically adjusted based on the evolving conditions of the search process. The adaptive \(S\) is calculated as follows:

where \(f_{\text {best}}\) represents the best fitness value among the current population, and \(f_{\text {global}}\) denotes the global best fitness value found so far. By applying the arctangent function to the absolute difference between \(f_{\text {best}}\) and \(f_{\text {global}}\), a dynamically adjusted value of \(S\) is obtained.

The arctangent function exhibits a characteristic where its output changes rapidly for small inputs and becomes more gradual for larger inputs. This property implies that when the difference between \(f_{\text {best}}\) and \(f_{\text {global}}\) is large, the computed value of \(S\) will also be relatively large, thereby enhancing exploration ability and helping the population escape local optima. Conversely, when the difference is small, \(S\) will decrease, allowing for more focused local search and improving exploitation during the later stages of optimization.

Through this adaptive adjustment mechanism, the somersault factor \(S\) varies dynamically according to the current search state, thereby autonomously achieving an appropriate equilibrium between global exploration and local refinement. This strategy effectively addresses the challenges associated with a fixed parameter \(S\), substantially enhancing the rate of convergence as well as the algorithm’s capability to perform a thorough global search, thereby enabling it to adapt more effectively to the changing requirements of the search process across different phases.

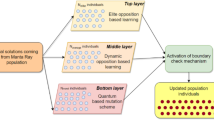

Hierarchical guidance mechanism in MRFO

In the enhanced MRFO, a hierarchical structure is incorporated to strengthen both the exploratory and exploitative abilities during the somersault foraging phase, thereby forming a hierarchical guidance mechanism. This hierarchical structure consists of four primary layers: the population layer, the personal-best layer, the archive layer, and the rank-based selective pressure layer. These layers play a crucial role in guiding the somersault foraging process.

Specifically, the original somersault foraging equation in MRFO is:

With the introduction of the hierarchical guidance mechanism, the somersault foraging equation is modified as follows:

In this new formula, the original \(x_{\text {best}}^{d}\) is replaced by \(x_{\text {Pbest}}^{d}(t)-x_{i}^{d}(t)+x_{R1}^{d}(t)-x_{R2}^{d}(t)\), thereby significantly enhancing the population’s ability to converge towards the global optimum. Specifically:

-

(1)

Population layer: This foundational layer encompasses all individuals. During the somersault foraging phase, each individual in the population layer adjusts its movement direction based on information provided by the other layers.

-

(2)

Personal-best layer: This layer is composed of the top \(P_{N}\) high-quality individuals from the population and serves as a replacement for the global best individual in the original algorithm. During the somersault foraging phase, one individual \(x_{\text {Pbest}}^{d}(t)\) is randomly selected from this layer to provide guidance for individuals within the population, thereby enhancing exploitation capability and effectively preventing convergence to local optima.

-

(3)

Archive layer: The archive layer stores individuals that were eliminated during the greedy selection process. These individuals provide diverse search directions, enriching population diversity. By randomly selecting individuals \(x_{R2}^{d}(t)\) from the archive layer, individuals can obtain more diverse movement directions.

-

(4)

Rank-based selective pressure layer: In this layer, all individuals are ranked based on their fitness, and one individual \(x_{R1}^{d}(t)\) is randomly selected to participate in the somersault foraging process. High-quality individuals have a higher probability of being selected, which helps accelerate convergence, while the occasional selection of lower-quality individuals promotes solution diversity and prevents premature convergence.

To better illustrate the working principle of the hierarchical guidance mechanism, Fig. 2 visually depicts the movement trajectory during the somersault foraging phase. In the figure, \(\bigstar\) represents the global optimum, and the positions of \(X_{\text {Pbest}}\) and \(X_{R1}\) are closer to the global optimum. The arrows in the figure represent the direction of movement, including vectors \(r_{2}(X_{\text {Pbest}} - X_i)\) and \(r_{2}(X_{R1} - X_{R2})\). The combination of these vectors results in an individual’s final movement direction that tends towards the global optimum, thereby enhancing the overall search capability and convergence performance of the population.

By incorporating the hierarchical layers, the somersault foraging phase is no longer confined to the original global best individual-based update strategy. Instead, it integrates information from the personal-best layer, archive layer, and rank-based selective pressure layer to dynamically adjust the individuals’ trade-off between broad exploration of the solution space and focused exploitation of promising regions. This improvement not only significantly enhances MRFO’s exploration capabilities but also bolsters its exploitation potential, allowing individuals to perform a more comprehensive exploration of the solution space and effectively circumvent local optima. The pseudocode for HGMRFO is provided in Algorithm 1.

Experiments and analysis

Experimental setup

To systematically evaluate the performance of HGMRFO, this study conducted simulations comparing HGMRFO with several state-of-the-art optimization algorithms on the IEEE CEC2017 benchmark function set. It should be noted that the F2 function was excluded from the experiments due to instability in the results. Additionally, to validate the practical applicability of HGMRFO, comparative experiments were carried out with other optimization algorithms on the IEEE CEC2011 real-world optimization problem set. Finally, to assess the performance of HGMRFO in parameter estimation for photovoltaic models, we selected six different photovoltaic models and compared HGMRFO with other methods for parameter estimation. For detailed descriptions of the IEEE CEC2017 benchmark function set, the IEEE CEC2011 real-world optimization problem set, and the photovoltaic models, please refer to references2,61,62.

In this paper, we conducted an experimental comparison on the IEEE CEC2017 benchmark functions and IEEE CEC2011 real-world optimization problems. For all comparison algorithms, the population size \(N=100\), and the maximum number of function evaluations (MFEs) was 10,000D, where \(D\) represents the problem dimension. Each algorithm was run independently 51 times on each function to ensure statistical significance of the results. In the parameter estimation experiments for photovoltaic (PV) models, \(N=100\) and \(MFEs=50,000\). Each algorithm was independently run 30 times for each parameter estimation problem to thoroughly evaluate its stability and effectiveness in practical application scenarios. The experiments were conducted in MATLAB R2021b, utilizing a computer featuring an Intel Core i7-9750H processor running at 2.60 GHz and 16 GB of RAM.

For the evaluation of experimental data, three distinct criteria were employed to comprehensively assess the performance of HGMRFO, as defined below:

1) Mean optimization error and standard deviation: The performance of each algorithm is evaluated by analyzing the optimization error generated in each iteration, which measures the difference between the solution obtained by the algorithm and the known global optimum. Each algorithm is executed independently across multiple trials, and the mean and standard deviation (std) of the optimization error are calculated to assess the robustness and reliability of its performance. The algorithm with the lowest mean error value is considered the most accurate, with this value highlighted in bold to indicate the best performance among all compared algorithms.

2) Wilcoxon rank-sum test63: It represents a non-parametric statistical approach employed to determine if a significant difference exists between the proposed algorithm and the comparison algorithm, using a significance level of \(\alpha = 0.05\). In the resulting test outcomes, the symbol “\(+\)” indicates that the proposed algorithm significantly outperforms its competitor, while the symbol “−” signifies that the proposed algorithm performs significantly worse. The symbol “\(\approx\)” implies that there is no significant difference between the two algorithms. Furthermore, “W/T/L” represents the number of times the proposed algorithm wins, ties, and loses against its competitors, providing a comprehensive assessment of the relative performance of the algorithms.

3) Friedman test64: It is also a non-parametric statistical approach that serves to evaluate the performance of all tested algorithms over the entire problem set and generate a comprehensive ranking. In this test, the mean optimization error of each algorithm is used as the test data, with a lower Friedman rank indicating superior algorithm performance. For clarity and ease of comparison, the smallest Friedman rank is highlighted in bold, emphasizing the best-performing algorithm.

Parameter sensitivity analysis

In the HGMRFO, the number of individuals in the personal-best layer is determined by the parameter \(\text {P}_{\text {rate}}\), calculated as \(P_{N} = \text {P}_{\text {rate}} \times N\). To evaluate the impact of \(\text {P}_{\text {rate}}\) on the algorithm’s performance, this study considers 10 possible values: \(\text {P}_{\text {rate}} \in \{0.02, 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, \text {rand}[0.02, 0.15], \text {rand}[0.02, 0.2], \text {rand}[0.02, 0.3]\}\). In the parameter sensitivity analysis, these values are used to regulate the size of the personal-best layer, enabling an assessment of the algorithm’s performance on the 30-dimensional IEEE CEC2017 benchmark function set under different configurations. By comparing the optimization results across different \(\text {P}_{\text {rate}}\) settings, we can gain insight into how this parameter influences HGMRFO’s convergence performance and global search capability.

The number of individuals in the archive layer is controlled by the parameter \(\text {A}_{\text {rate}}\), calculated as \(A_{N} = \text {A}_{\text {rate}} \times N\). To comprehensively evaluate the effect of archive size on the performance of HGMRFO, \(\text {A}_{\text {rate}}\) is set to 7 different values: \(\text {A}_{\text {rate}} \in \{1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4\}\). In the experiments, these values are used to adjust the size of the archive layer, and the impact on performance is assessed using the IEEE CEC2017 benchmark function set. Proper configuration of the archive layer is crucial for maintaining population diversity and preventing premature convergence. By comparing the results for different \(\text {A}_{\text {rate}}\) settings, we aim to identify the optimal archive size that best balances exploration and exploitation at various stages of the optimization process.

The sensitivity analysis of parameters \(\text {P}_{\text {rate}}\) and \(\text {A}_{\text {rate}}\) aims to determine the optimal parameter configurations that enhance the performance of HGMRFO on complex optimization problems, improve its global search ability, and increase its local exploitation precision, thereby improving the algorithm’s overall solution efficiency and robustness. Tables 1 and 2 present the experimental results of HGMRFO across different parameter settings on the IEEE CEC2017 benchmark functions. Analysis of the W/T/L metrics in these tables indicates that the algorithm demonstrates limited sensitivity to the parameters \(\text {P}_{\text {rate}}\) and \(\text {A}_{\text {rate}}\). However, according to the Friedman test rankings, HGMRFO achieves the best performance with \(\text {P}_{\text {rate}} = \text {rand}[0.02, 0.2]\) and \(\text {A}_{\text {rate}} = 3.5\). This implies that, although the algorithm is generally robust to variations in these parameters, specific configurations can still lead to statistically significant improvements in performance.

Analysis of hierarchical interactions

To comprehensively evaluate the efficacy of various hierarchical structures within the HGMRFO, five distinct hierarchical schemes, denoted as L1 through L5, were systematically compared as follows:

-

L1: Personal-best layer only

-

L2: Personal-best layer + Population layer

-

L3: Rank-based selective pressure layer + Archive layer

-

L4: Personal-best layer + Population layer + Rank-based selective pressure layer + Archive layer (i.e., HGMRFO)

-

L5: Current best individual + Population layer + Rank-based selective pressure layer + Archive layer

These five schemes were subjected to experimental evaluation on the CEC2017 suite to thoroughly assess their relative performances, as shown in Table 3.

The experimental results unequivocally demonstrate that L4, the complete version of HGMRFO, which integrates the personal-best layer, population layer, rank-based selective pressure layer, and archive layer, consistently outperformed the other hierarchical schemes in terms of optimization accuracy. Specifically, HGMRFO achieved a more optimal balance between global exploration and local exploitation, enhancing its capability to prevent premature convergence and obtain superior overall solutions.

Notably, the comparison between L4 and L1 underscores the critical importance of incorporating additional layers, such as the rank-based selective pressure layer and archive layer, in enhancing the robustness and search diversity of the algorithm. Similarly, comparisons with L5 reveal that leveraging a dynamically updated personal-best layer, rather than merely relying on the current best individual, provides more effective guidance, ultimately leading to enhanced optimization outcomes.

The comparison between L4 and L2 highlights the impact of adding both the rank-based selective pressure layer and the archive layer. While L2 already incorporates the population layer to complement the personal-best layer, L4 further enhances the search process by utilizing rank-based selective pressure to guide the population more effectively towards promising regions and by incorporating an archive layer to maintain search diversity. This combination enhances resilience against early convergence and optimizes the utilization of the solution space.

Furthermore, the comparison between L4 and L3 reveals the critical role of the personal-best layer in conjunction with the rank-based selective pressure layer and archive layer. L3, which lacks the personal-best layer, showed limited guidance efficiency, leading to suboptimal convergence. By incorporating the personal-best layer, L4 substantially enhanced the algorithm’s capacity to fine-tune the exploration process and attain superior-quality solutions, underscoring the importance of integrating all four layers to achieve optimal performance.

Overall, the experimental analysis substantiates that the complete hierarchical configuration of HGMRFO (L4) significantly improves the algorithm’s performance, emphasizing the importance of each layer in facilitating a comprehensive and effective exploration of the solution space.

Comparison for competitive algorithms

To rigorously evaluate the performance of the HGMRFO, comparative experiments were conducted against several state-of-the-art algorithms, including the original MRFO13, the fractional-order Caputo MRFO (FCMRFO)27, chaotic wind driven optimization with fitness distance balance strategy (CFDBWDO)65, spatial information sampling algorithm (SIS)66, reptile search algorithm (RSA)67, the fractional-order flower pollination algorithm (FOFPA)68, and spherical evolution (SE)69, on the IEEE CEC2017 benchmark functions with dimensions of 10, 30, 50, and 100. The statistical results derived from these experiments are presented in Table 5, with the experimental data provided in Tables 8, 9, 10, and 11, while the specific parameter settings for each algorithm are detailed in Table 4.

In the statistical results presented in Table 5, HGMRFO demonstrated superior performance across various dimensions of the IEEE CEC2017 benchmark functions. Specifically, in the 10-dimensional benchmark, HGMRFO outperformed MRFO, FCMRFO, CFDBWDO, SIS, RSA, FOFPA, and SE on 15, 11, 27, 22, 29, 23, and 13 problems, respectively, achieving the top rank according to the Friedman test. These results indicate that HGMRFO exhibits remarkable performance in low-dimensional optimization tasks.

In the 30-dimensional benchmark, HGMRFO outperformed the aforementioned algorithms on 21, 19, 28, 21, 28, 24, and 17 problems, respectively, with the highest Friedman ranking. This signifies the strong competitiveness of HGMRFO in medium-dimensional problems.

For the 50-dimensional benchmark, the W/T/L (Wins/Ties/Losses) metric demonstrates that HGMRFO performed better than MRFO, FCMRFO, CFDBWDO, SIS, RSA, FOFPA, and SE on 17, 15, 27, 18, 29, 26, and 17 problems, respectively. It also achieved the smallest Friedman rank, indicating that HGMRFO excels in high-dimensional optimization scenarios.

In the 100-dimensional benchmark, HGMRFO outperformed the competing algorithms on 17, 17, 25, 18, 28, 24, and 18 problems, respectively, while maintaining the smallest rank value, thereby showcasing its effectiveness in ultra-high-dimensional optimization tasks.

The statistical analysis across different dimensions conclusively demonstrates that HGMRFO consistently achieves superior performance, affirming its robustness and high efficiency in handling complex optimization problems of varying dimensionality.

In Table 8, HGMRFO achieved the best solution on 6 out of 10-dimensional functions, while SE obtained the best solution on 12 functions, ranking first in terms of the number of best solutions, with HGMRFO ranking second. Therefore, for low-dimensional functions, the proposed HGMRFO still requires further improvement in future research.

In Tables 9, 10, and 11, HGMRFO achieved the best solution on 15 out of 30-dimensional functions, 10 out of 50-dimensional functions, and 11 out of 100-dimensional functions, respectively, ranking first in terms of the number of best solutions obtained. Thus, HGMRFO demonstrates the best performance on 30-dimensional, 50-dimensional, and 100-dimensional functions.

Fig. 4 shows the convergence curves of the average optimization errors for HGMRFO and other competing algorithms on the F8 and F11 functions across 10-dimensional, 30-dimensional, 50-dimensional, and 100-dimensional spaces. As can be seen from the figure, HGMRFO demonstrates rapid convergence and consistently finds the optimal solution in all dimensions. Compared to the original MRFO algorithm, the figure clearly illustrates the effectiveness of the hierarchical guidance mechanism proposed in this paper.

The computational complexity of each iteration in the HGMRFO algorithm is primarily determined by the following components:

-

(1)

Initialization: \(O(N \times D)\).

-

(2)

Fitness evaluation: \(O(N)\).

-

(3)

Best individual update: \(O(N)\).

-

(4)

Position update: \(O(N \times D)\).

-

(5)

Boundary detection: \(O(N \times D)\).

-

(6)

Archive update: \(O(N \times D)\).

-

(7)

Probability calculation and selection: \(O(N)\).

Therefore, the overall computational complexity for a single iteration is: \(O(N \times D)\). If the algorithm runs for T iterations, the total computational complexity becomes: \(O(T \times N \times D)\).

Furthermore, Fig. 3 illustrates a bar chart that shows the computational running times for each algorithm tested on the IEEE CEC2017 benchmark set with dimensions of 10, 30, 50, and 100. As illustrated in Fig. 3, both HGMRFO and MRFO exhibit the shortest CPU running times across all dimensions, with computational complexities that are nearly identical. These results suggest that the introduction of the hierarchical guidance structure in HGMRFO imposes negligible computational overhead on MRFO, thus affirming the scalability and efficiency of HGMRFO. Additionally, the low computational cost of HGMRFO highlights its potential for application in high-dimensional and intricate engineering optimization problems.

Real-world optimization problems

To comprehensively assess the practicality of the HGMRFO, we conducted extensive simulation experiments comparing HGMRFO with eight state-of-the-art algorithms on real-world optimization problems from the IEEE CEC2011 benchmark suite. The algorithms considered in this comparison include: MRFO13, FCMRFO27, HMRFO12, disGSA70, AHA71, SIS66, DGSA72, and XPSO73. Among them, HMRFO is an hierarchical MRFO with weighted fitness-distance balance selection. disGSA is an adaptive position-guided GSA. AHA denotes the artificial hummingbird algorithm. DGSA is a GSA with hierarchy and distributed framework. XPSO is an expanded PSO based on multi-exemplar and forgetting ability. The specific parameter settings for each algorithm are detailed in Table 4. The experimental data and statistical results are presented in Tables 6 and 7.

From the results summarized in Tables 6 and 7, it can be observed that HGMRFO achieved the best mean values on eight distinct problems, outperforming the competing algorithms by achieving the highest number of optimal solutions. Furthermore, the W/T/L analysis indicates that HGMRFO outperformed MRFO, FCMRFO, HMRFO, disGSA, AHA, SIS, DGSA, and XPSO on 7, 8, 7, 12, 14, 16, 11, and 11 problems, respectively. These results highlight the effectiveness and practical applicability of HGMRFO in addressing real-world optimization challenges.

The demonstrated superior performance, combined with the low computational overhead of HGMRFO, motivated us to apply this algorithm to a practical engineering problem-parameter estimation in solar photovoltaic models.

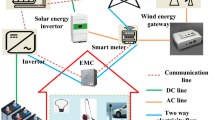

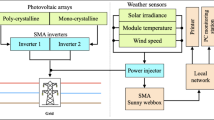

Comparison on parameter estimation of photovoltaic model

To thoroughly analyze the nonlinear output characteristics of photovoltaic (PV) systems, the adoption of accurate mathematical models for PV cells is crucial. The output characteristics of PV cells are significantly influenced by various factors, including temperature and internal as well as external circuit parameters. Consequently, the development of precise mathematical models is essential for predicting system performance, optimizing system design, and improving energy conversion efficiency. To meet diverse research and application requirements, various PV models have been developed, spanning from simple to more complex structures. These models include the single diode model (SDM)74, the double diode model (DDM)75, the triple diode model (TDM)76, and more complex PV module models (MM)77. The structures of these models are shown in Fig. 5, with a detailed description provided below.

The output current \(I_L\) of the SDM can be determined using the equation below:

where, \(I_{ph}\) denotes the photo-generated current, which is the current generated due to illumination, \(I_d\) is the diode current, \(I_{sh}\) is the current through the shunt resistance, \(I_{sd}\) denotes the reverse saturation current of the diode, \(V_L\) is the output voltage, \(R_s\) is the series resistance, \(R_{sh}\) is the shunt resistance, \(a\) is the diode ideality factor, \(q\) is the electron charge (\(1.60217646 \times 10^{-19}\) C), \(k\) is the Boltzmann constant (\(1.3806503 \times 10^{-23}\) J/K), and \(T\) is the cell temperature in Kelvin. In the SDM, five parameters need to be estimated: \(I_{ph}\), \(I_{sd}\), \(R_s\), \(R_{sh}\), and \(a\).

The output current \(I_L\) of the DDM can be determined using the equation below:

where \(I_{\text {sd1}}\) is the diffusion current, \(I_{\text {sd2}}\) is the saturation current, and \(a_1\) and \(a_2\) are the ideality factors of the two diodes. In the DDM, seven parameters need to be estimated: \(I_{ph}\), \(I_{sd1}\), \(I_{sd2}\), \(R_s\), \(R_{sh}\), \(a_1\) and \(a_2\).

The output current \(I_{\text {L}}\) of the TDM can be determined using the equation below:

where \(I_{\text {sd3}}\) is leakage current. In the TDM, nine parameters need to be estimated: \(I_{ph}\), \(I_{sd1}\), \(I_{sd2}\), \(I_{sd3}\), \(R_s\), \(R_{sh}\), \(a_1\), \(a_2\) and \(a_3\).

The PV current of MM can be determined by the following equation:

where \(N_{\text {p}}\) is the number of solar cells connected in parallel, and \(N_{\text {s}}\) is the number of solar cells connected in series. In the MM, five parameters need to be estimated: \(I_{ph}\), \(I_{sd}\), \(R_s\), \(R_{sh}\), and \(a\). The objective function for parameter estimation is achieved by minimizing the error between the measured current data and the experimental current data2.

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed HGMRFO, six groups of experiments were designed to encompass different numbers of series diodes (Ns) and parallel diodes (Np). For the SDM, DDM, and TDM, experimental data were obtained from a commercial silicon solar cell produced by R.T.C. France, with 26 sets of current-voltage data measured at a temperature of \({33}^\circ\)C78. For the photovoltaic MM, the experimental data were sourced from Photowatt-PWP201, STP6-120/36, and STM6-40/36 PV modules, under varying temperature and irradiance conditions78,79. Table 12 presents a comprehensive overview of the true value sources, measurement conditions, and the number of experimental data points for each model. Additionally, Table 13 presents the lower bounds (LB) and upper bounds (UB) for parameter extraction in each model80,81,82. In these six experimental setups, the HGMRFO was systematically compared against seven other advanced optimization algorithms. These algorithms include the original MRFO13, FCMRFO27, HMRFO12, water flow optimizer (WFO)83, fractional-order WFO (FOWFO)84, wind driven optimization (WDO)85, and grey wolf optimizer (GWO)86. The configuration of parameters for all algorithms is summarized in Table 4. The experimental data and statistical results are presented in Table 14.

As presented in Table 14, HGMRFO achieved the best mean values across all photovoltaic (PV) models. Specifically, HGMRFO outperformed MRFO, FCMRFO, HMRFO, FOWFO, WFO, WDO, and GWO in 6, 6, 5, 6, 6, 6, and 6 PV models, respectively. According to the Friedman test ranks, HGMRFO is ranked first, indicating that HGMRFO outperforms other competing algorithms. These results clearly demonstrate the superior performance of HGMRFO in addressing the parameter estimation challenges associated with solar PV models, underscoring its efficacy and robustness in tackling such complex optimization problems.

Figure 6 presents the box-and-whisker diagrams of errors for HGMRFO and seven other algorithms across six photovoltaic models. The median, indicated by the red horizontal line, represents the average performance of the algorithms. From the figure, it can be seen that HGMRFO has the lowest median on the SDM, DDM, TDM, STP6-120/36, and STM6-40/36 models, indicating that HGMRFO performs best on these five models. However, on the Photowatt-PWP201 model, HGMRFO slightly underperforms compared to HMRFO, although its overall performance remains strong. The box-and-whisker diagrams demonstrate that HGMRFO exhibits excellent robustness and accuracy on PV models.

Conclusions

In this study, we address the limitations of the MRFO during the somersault foraging phase, specifically the fixed parameter setting and the exclusive focus on the current best individual during the somersault search. To overcome these limitations, we introduce an adaptive somersault factor and a hierarchical guidance mechanism, enhancing the information exchange among population individuals. Through the synergistic effect of a multi-layered structure, individuals are effectively guided towards the global optimal solution, thereby proposing an enhanced algorithm named hierarchical guided manta ray foraging optimization (HGMRFO). During the experimental phase, we initially identified the optimal parameter configurations for HGMRFO and conducted a systematic analysis of how different hierarchical structures influence the algorithm’s performance. Extensive experiments on the IEEE CEC2017 benchmark functions and IEEE CEC2011 real-world optimization problems confirmed the significant advantages of HGMRFO in terms of optimization performance and practical applicability, demonstrating its lower computational cost and superior efficiency. Finally, HGMRFO was utilized for parameter estimation in solar photovoltaic models with multimodal characteristics, yielding excellent experimental outcomes and further demonstrating the potential and efficacy of this algorithm in addressing complex real-world problems.

In future research, we intend to focus on the following five areas:

-

1.

Further enhancement for low-dimensional optimization problems: Based on the optimization results on the CEC2017 benchmark functions with 10 dimensions, particularly in comparison with SE, it is evident that HGMRFO requires further refinement for better performance in low-dimensional optimization tasks.

-

2.

Improvement in selection methods for HGMRFO: In the boxplot analysis of the PV models, HGMRFO performed weaker than HMRFO on the Photowatt-PWP201 model. In the future, we could draw inspiration from the fitness-distance balance selection strategy in HMRFO12 to improve the selection method in HGMRFO.

-

3.

Extension of hierarchical guidance mechanism: We will explore the integration of the hierarchical guidance mechanism into other optimization algorithms to further enhance their performance and robustness.

-

4.

Investigation of alternative population structures: We aim to study various alternative population structures in an effort to identify more sophisticated configurations that could improve the structural characteristics of the original algorithm, thereby contributing to overall optimization efficiency.

-

5.

Application of HGMRFO to additional real-world problems: We plan to apply HGMRFO to other complex real-world problems, such as the protein structure prediction87,88 and dendritic neural model89,90,91, to validate its versatility and effectiveness in diverse domains.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Zhang, Z. et al. Triple-layered chaotic differential evolution algorithm for layout optimization of offshore wave energy converters. Expert Syst. Appl. 239, 122439 (2024).

Gao, S. et al. A state-of-the-art differential evolution algorithm for parameter estimation of solar photovoltaic models. Energy Convers. Manage. 230, 113784 (2021).

Zhang, B. et al. Information gain-based multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for feature selection. Inf. Sci. 677, 120901 (2024).

Kramer, O. Genetic Algorithm Essentials Vol. 679 (Springer, 2017).

Wang, D., Tan, D. & Liu, L. Particle swarm optimization algorithm: An overview. Soft. Comput. 22, 387–408 (2018).

Dorigo, M. & Stützle, T. Ant colony optimization: overview and recent advances. In Handbook of Metaheuristics, 311–351 (Springer, 2019).

Rashedi, E., Nezamabadi-Pour, H. & Saryazdi, S. GSA: A gravitational search algorithm. Inf. Sci. 179, 2232–2248 (2009).

Wang, X. Draco lizard optimizer: A novel metaheuristic algorithm for global optimization problems. Evol. Intel. 18, 10 (2025).

Wang, X. Eurasian lynx optimizer: A novel metaheuristic optimization algorithm for global optimization and engineering applications. Phys. Scr. 99, 115275 (2024).

Wang, X. Artificial meerkat algorithm: A new metaheuristic algorithm for solving optimization problems. Phys. Scr. 99, 125280 (2024).

Wang, Y., Gao, S., Zhou, M. & Yu, Y. A multi-layered gravitational search algorithm for function optimization and real-world problems. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 8, 94–109 (2021).

Tang, Z. et al. Hierarchical manta ray foraging optimization with weighted fitness-distance balance selection. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 16, 114 (2023).

Zhao, W., Zhang, Z. & Wang, L. Manta ray foraging optimization: An effective bio-inspired optimizer for engineering applications. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 87, 103300 (2020).

Tang, A., Zhou, H., Han, T. & Xie, L. A modified manta ray foraging optimization for global optimization problems. IEEE Access 9, 128702–128721 (2021).

Xu, X. et al. A novel calibration method for robot kinematic parameters based on improved manta ray foraging optimization algorithm. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 72, 1–11 (2023).

Rizk-Allah, R. M. et al. On a novel hybrid manta ray foraging optimizer and its application on parameters estimation of lithium-ion battery. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 15, 62 (2022).

El-Shorbagy, M. A., Omar, H. A. & Fetouh, T. Hybridization of manta-ray foraging optimization algorithm with pseudo parameter-based genetic algorithm for dealing optimization problems and unit commitment problem. Mathematics 10, 2179 (2022).

Ekinci, S., Izci, D. & Kayri, M. An effective controller design approach for magnetic levitation system using novel improved manta ray foraging optimization. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 47, 9673–9694 (2022).

Abdul Razak, A. A., Nasir, A. N. K., Abdul Ghani, N. M. & Tokhi, M. O. Opposition-based manta ray foraging algorithm for global optimization and its application to optimize nonlinear type-2 fuzzy logic control. J. Low Freq. Noise Vib. Active Control 43, 1339–1362 (2024).

Ekinci, S., Izci, D. & Hekimoğlu, B. Optimal FOPID speed control of DC motor via opposition-based hybrid manta ray foraging optimization and simulated annealing algorithm. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 46, 1395–1409 (2021).

Zhang, K. et al. IBMRFO: Improved binary manta ray foraging optimization with chaotic tent map and adaptive somersault factor for feature selection. Expert Syst. Appl. 251, 123977 (2024).

Qu, P., Yuan, Q., Du, F. & Gao, Q. An improved manta ray foraging optimization algorithm. Sci. Rep. 14, 10301 (2024).

Got, A., Zouache, D. & Moussaoui, A. MOMRFO: Multi-objective manta ray foraging optimizer for handling engineering design problems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 237, 107880 (2022).

Zhong, C., Li, G., Meng, Z., Li, H. & He, W. Multi-objective SHADE with manta ray foraging optimizer for structural design problems. Appl. Soft Comput. 134, 110016 (2023).

Singh, S., Kumar, R. & Rao, U. P. Multi-objective adaptive manta-ray foraging optimization for workflow scheduling with selected virtual machines using time-series-based prediction. Int. J. Softw. Sci. Comput. Intell. 14, 1–25 (2022).

Haddadian Nezhad, E., Ebrahimi, R. & Ghanbari, M. Fuzzy multi-objective allocation of photovoltaic energy resources in unbalanced network using improved manta ray foraging optimization algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 234, 121048 (2023).

Yousri, D. et al. Discrete fractional-order Caputo method to overcome trapping in local optima: Manta ray foraging optimizer as a case study. Expert Syst. Appl. 192, 116355 (2022).

Zhu, D., Wang, S., Zhou, C. & Yan, S. Manta ray foraging optimization based on mechanics game and progressive learning for multiple optimization problems. Appl. Soft Comput. 145, 110561 (2023).

Got, A., Zouache, D., Moussaoui, A., Abualigah, L. & Alsayat, A. Improved manta ray foraging optimizer-based SVM for feature selection problems: A medical case study. J. Bionic Eng. 21, 409–425 (2024).

Karrupusamy, P. Hybrid manta ray foraging optimization for novel brain tumor detection. J. Soft Comput. Paradigm (JSCP) 02, 175–185 (2020).

Rawat, N. & Thakur, P. Comparative analysis of hybrid and metaheuristic parameter estimation methods of solar PV. Mater. Today Proc. 65, 3748–3756 (2022).

Rawat, N., Thakur, P. & Singh, A. K. A novel hybrid parameter estimation technique of solar PV. Int. J. Energy Res. 46, 4919–4934 (2022).

Rawat, N. et al. A new grey wolf optimization-based parameter estimation technique of solar photovoltaic. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 57, 103240 (2023).

Rawat, N., Thakur, P., Singh, A. K. & Bansal, R. Performance analysis of solar PV parameter estimation techniques. Optik 279, 170785 (2023).

Sharma, P., Raju, S., Salgotra, R. & Gandomi, A. H. Parametric estimation of photovoltaic systems using a new multi-hybrid evolutionary algorithm. Energy Rep. 10, 4447–4464 (2023).

Rathod, A. A. & Subramanian, B. Efficient approach for optimal parameter estimation of PV using Pelican Optimization Algorithm. Cogent Eng. 11, 2380805 (2024).

Sundar Ganesh, C. S., Kumar, C., Premkumar, M. & Derebew, B. Enhancing photovoltaic parameter estimation: Integration of non-linear hunting and reinforcement learning strategies with golden jackal optimizer. Sci. Rep. 14, 2756 (2024).

Beskirli, A., Dag, I. & Kiran, M. S. A tree seed algorithm with multi-strategy for parameter estimation of solar photovoltaic models. Appl. Soft Comput. 167, 112220 (2024).

Rawat, N., Thakur, P., Dixit, A., Charu, K. & Goyal, S. Grey wolf optimisation based modified parameter estimation technique of solar PV. In 2024 IEEE Third International Conference on Power Electronics, Intelligent Control and Energy Systems (ICPEICES), 755–760 (IEEE, 2024).

Charu, K. M. et al. An efficient data sheet based parameter estimation technique of solar PV. Sci. Rep. 14, 6461 (2024).

Dorronsoro, B. & Bouvry, P. Improving classical and decentralized differential evolution with new mutation operator and population topologies. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 15, 67–98 (2011).

Lynn, N., Ali, M. Z. & Suganthan, P. N. Population topologies for particle swarm optimization and differential evolution. Swarm Evol. Comput. 39, 24–35 (2018).

Cantú-Paz, E. Efficient and Accurate Parallel Genetic Algorithms Vol. 1 (Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2000).

Alba, E. & Tomassini, M. Parallelism and evolutionary algorithms. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 6, 443–462 (2002).

Dorronsoro, B. & Alba, E. Cellular Genetic Algorithms Vol. 42 (Springer, 2008).

Dorronsoro, B. & Bouvry, P. Differential evolution algorithms with cellular populations. In Parallel Problem Solving from Nature, PPSN XI, 320–330 (Springer, 2010).

Nabizadeh, S., Rezvanian, A. & Meybodi, M. R. A multi-swarm cellular PSO based on clonal selection algorithm in dynamic environments. In 2012 International Conference on Informatics, Electronics & Vision (ICIEV), 482–486 (IEEE, 2012).

Liao, J., Cai, Y., Wang, T., Tian, H. & Chen, Y. Cellular direction information based differential evolution for numerical optimization: An empirical study. Soft. Comput. 20, 2801–2827 (2016).

Liang, J. & Suganthan, P. Dynamic multi-swarm particle swarm optimizer. In Proceedings 2005 IEEE Swarm Intelligence Symposium, 2005. SIS 2005., 124–129 (IEEE, 2005).

El Dor, A., Clerc, M. & Siarry, P. A multi-swarm PSO using charged particles in a partitioned search space for continuous optimization. Comput. Optim. Appl. 53, 271–295 (2012).

Cheng, J., Zhang, G. & Neri, F. Enhancing distributed differential evolution with multicultural migration for global numerical optimization. Inf. Sci. 247, 72–93 (2013).

Gong, Y.-J. et al. Distributed evolutionary algorithms and their models: A survey of the state-of-the-art. Appl. Soft Comput. 34, 286–300 (2015).

Janson, S. & Middendorf, M. A hierarchical particle swarm optimizer and its adaptive variant. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. B 35, 1272–1282 (2005).

Wang, K., Lei, Z., Wang, Z., Zhang, Z. & Gao, S. Deep-layered differential evolution. In Advances in Swarm Intelligence, 503–515 (Springer, 2023).

Giacobini, M., Preuss, M. & Tomassini, M. Effects of scale-free and small-world topologies on binary coded self-adaptive CEA. In Evolutionary Computation in Combinatorial Optimization, 86–98 (Springer, 2006).

Zhang, C. & Yi, Z. Scale-free fully informed particle swarm optimization algorithm. Inf. Sci. 181, 4550–4568 (2011).

Yu, Y. et al. Scale-free network-based differential evolution to solve function optimization and parameter estimation of photovoltaic models. Swarm Evol. Comput. 74, 101142 (2022).

Lieberman, E., Hauert, C. & Nowak, M. A. Evolutionary dynamics on graphs. Nature 433, 312–316 (2005).

Gao, S., Wang, Y., Wang, J. & Cheng, J. Understanding differential evolution: A poisson law derived from population interaction network. J. Comput. Sci. 21, 140–149 (2017).

Wang, Y., Gao, S., Yu, Y. & Xu, Z. The discovery of population interaction with a power law distribution in brain storm optimization. Mem. Comput. 11, 65–87 (2019).

Awad, N., Ali, M., Liang, J., Qu, B. & Suganthan, P. Problem definitions and evaluation criteria for the CEC 2017 special session and competition on single objective bound constrained real-parameter numerical optimization. In Technical Report (Nanyang Technological University Singapore, 2016).

Das, S. & Suganthan, P. N. Problem definitions and evaluation criteria for CEC 2011 competition on testing evolutionary algorithms on real world optimization problems. Jadavpur University, Nanyang Technological University, Kolkata 341–359 (2010).

Luengo, J., García, S. & Herrera, F. A study on the use of statistical tests for experimentation with neural networks: Analysis of parametric test conditions and non-parametric tests. Expert Syst. Appl. 36, 7798–7808 (2009).

Carrasco, J., García, S., Rueda, M., Das, S. & Herrera, F. Recent trends in the use of statistical tests for comparing swarm and evolutionary computing algorithms: Practical guidelines and a critical review. Swarm Evol. Comput. 54, 100665 (2020).

Tang, Z. et al. Chaotic wind driven optimization with fitness distance balance strategy. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 15, 46 (2022).

Yang, H. et al. An intelligent metaphor-free spatial information sampling algorithm for balancing exploitation and exploration. Knowl.-Based Syst. 250, 109081 (2022).

Abualigah, L., Elaziz, M. A., Sumari, P., Geem, Z. W. & Gandomi, A. H. Reptile search algorithm (RSA): A nature-inspired meta-heuristic optimizer. Expert Syst. Appl. 191, 116158 (2022).

Yousri, D., Elaziz, M. A. & Mirjalili, S. Fractional-order calculus-based flower pollination algorithm with local search for global optimization and image segmentation. Knowl.-Based Syst. 197, 105889 (2020).

Tang, D. Spherical evolution for solving continuous optimization problems. Appl. Soft Comput. 81, 105499 (2019).

Guo, A. et al. An adaptive position-guided gravitational search algorithm for function optimization and image threshold segmentation. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 121, 106040 (2023).

Zhao, W., Wang, L. & Mirjalili, S. Artificial hummingbird algorithm: A new bio-inspired optimizer with its engineering applications. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 388, 114194 (2022).

Wang, Y., Gao, S., Yu, Y., Cai, Z. & Wang, Z. A gravitational search algorithm with hierarchy and distributed framework. Knowl.-Based Syst. 218, 106877 (2021).

Xia, X. et al. An expanded particle swarm optimization based on multi-exemplar and forgetting ability. Inf. Sci. 508, 105–120 (2020).

Ram, J. P. et al. Analysis on solar PV emulators: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 81, 149–160 (2018).

Ishaque, K., Salam, Z. & Syafaruddin, A. A comprehensive MATLAB simulink PV system simulator with partial shading capability based on two-diode model. Sol. Energy 85, 2217–2227 (2011).

Allam, D., Yousri, D. & Eteiba, M. Parameters extraction of the three diode model for the multi-crystalline solar cell/module using moth-flame optimization algorithm. Energy Convers. Manage. 123, 535–548 (2016).

El-Naggar, K., AlRashidi, M., AlHajri, M. & Al-Othman, A. Simulated annealing algorithm for photovoltaic parameters identification. Sol. Energy 86, 266–274 (2012).

Easwarakhanthan, T., Bottin, I. B. J. & Boutrit, C. Nonlinear minimization algorithm for determining the solar cell parameters with microcomputers. Int. J. Sol. Energy 4, 1–12 (1986).

Tong, N. T. & Pora, W. A parameter extraction technique exploiting intrinsic properties of solar cells. Appl. Energy 176, 104–115 (2016).

Liang, J. et al. Parameters estimation of solar photovoltaic models via a self-adaptive ensemble-based differential evolution. Sol. Energy 207, 336–346 (2020).

Yang, X., Gong, W. & Wang, L. Comparative study on parameter extraction of photovoltaic models via differential evolution. Energy Convers. Manage. 201, 112113 (2019).

Askarzadeh, A. & Rezazadeh, A. Parameter identification for solar cell models using harmony search-based algorithms. Sol. Energy 86, 3241–3249 (2012).

Luo, K. Water flow optimizer: A nature-inspired evolutionary algorithm for global optimization. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 52, 7753–7764 (2022).

Tang, Z. et al. Fractional-order water flow optimizer. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 17, 84 (2024).

Bayraktar, Z., Komurcu, M. & Werner, D. H. Wind driven optimization (WDO): A novel nature-inspired optimization algorithm and its application to electromagnetics. In 2010 IEEE Antennas and Propagation Society International Symposium, 1–4 (IEEE, 2010).

Mirjalili, S., Mirjalili, S. M. & Lewis, A. Grey wolf optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw. 69, 46–61 (2014).

Lei, Z., Gao, S., Zhang, Z., Zhou, M. & Cheng, J. MO4: A many-objective evolutionary algorithm for protein structure prediction. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 26, 417–430 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Gao, S., Cai, P., Lei, Z. & Wang, Y. Information entropy-based differential evolution with extremely randomized trees and lightGBM for protein structural class prediction. Appl. Soft Comput. 136, 110064 (2023).

Gao, S. et al. Dendritic neuron model with effective learning algorithms for classification, approximation, and prediction. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 30, 601–614 (2019).

Gao, S. et al. Fully complex-valued dendritic neuron model. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 34, 2105–2118 (2023).

Yu, Y. et al. Improving dendritic neuron model with dynamic scale-free network-based differential evolution. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 9, 99–110 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was mainly supported by the Research on Deep-layered Swarm Intelligence Algorithms and Their Application in Solar Photovoltaic Models under Grant NSF2024CB14.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhentao Tang: Writing- original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization, Software. Kaiyu Wang: Formal analysis, Writing- review & editing, Conceptualization. Lan Zhuang: Formal analysis, Writing- review & editing, Conceptualization. Mingxin Zhu: Data curation, Writing- review & editing. Yongxuan Yao: Data curation, Writing- review & editing. Huiqin Chen: Data curation, Writing- review & editing. Jing Li: Formal analysis, Validation. Xiaoxiang Wu: Formal analysis, Validation. Shangce Gao: Writing- review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

No human or animal subjects were involved in this experiment.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, Z., Wang, K., Zhuang, L. et al. Hierarchical guided manta ray foraging optimization for global continuous optimization problems and parameter estimation of solar photovoltaic models. Sci Rep 15, 26401 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90867-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90867-7