Abstract

The frequency and intensity of massive natural disasters are increasing significantly with climate change. In response, the need and interest in disaster response systems are increasing. One of the disaster response’s most important activities is delivering relief resources. This process has distinct characteristics from the general logistics environment, such as uncertainty in information transmission and the importance of deadlines. To enhance the efficiency of this process, a new distributed emergency logistics system is proposed by focusing on emergency logistics for the delivery of relief resources. In the proposed system, to overcome the uncertainty in information transmission, the distributed agent architecture which is applied to facility management and vehicle planning is adopted. In this system, each vehicle as an agent and facility gathers up-to-date information and generates its plan; then, the generated plans are coordinated through communication between vehicles. The proposed algorithm was evaluated through simulation experiments based on the Korean urban environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The frequency of massive disasters such as typhoons, earthquakes, and nuclear incidents has grown continuously since the 2000s. Moreover, the impact of these massive disasters has increased in severity. On average, natural disasters have killed 60,000 people per year in the last decade. As shown in Fig. 1, an unexpected natural disaster causes massive deaths. Due to the disordered urbanization in developing countries and worldwide abnormal climate change effects, more damage has been predicted to occur from natural disasters, and this was realized with COVID-19. Therefore, the need for efficient disaster responses has increased. To respond to disasters and reduce damage, activities such as the organization of disaster response groups, the securement of delivery routes, the procurement of relief resources, the transportation of relief resources and rescue teams, and the reconstruction of damaged areas are needed.

Among these activities, the efficient transportation of relief resources to victims is one of the most essential activities. Figure 2 illustrates a cyclical disaster management process, highlighting key activities and stages involved in reducing risk, preparing for potential disasters, responding to emergencies, and recovering from their impacts.

-

Mitigation is the first step in disaster management. It focuses on reducing risks and minimizing disaster impacts through proactive measures. Risk assessment helps identify hazards like earthquakes, floods, and hurricanes while evaluating their likelihood and severity. This information is important for guiding preparedness and response efforts. Infrastructure planning ensures that critical systems, such as roads, hospitals, and communication networks, are resilient. It involves protecting, maintaining, and preparing for their repair or replacement. Policy making strengthens disaster management through regulations like building codes and land-use planning to enhance safety. Capacity planning ensures communities and organizations have the resources, trained personnel, and emergency response teams to handle disasters. Training and education raise public awareness about disaster preparedness, safety measures, and evacuation procedures. They also equip emergency responders with essential skills. These mitigation strategies work together to reduce disaster risks and build a more resilient society.

-

Preparedness focuses on ensuring readiness before a disaster strikes. Resident and refuge planning helps protect communities by creating evacuation plans, identifying safe zones, and setting up communication networks. Refuge allocation ensures resources, like shelters and medical centers, are available for displaced populations during and after the disaster. Prepositioning resources involves strategically storing essential supplies such as food, water, medical equipment, and emergency tools. This allows quick access to aid when needed. Damage forecasting estimates potential destruction to infrastructure, property, and the environment. This information helps with recovery planning and strengthens preparedness efforts.

-

The response stage begins immediately after a disaster to minimize harm and provide aid. Resident and casualty evacuation ensures safe relocation and medical assistance for the injured. Relief goods distribution provides essential items like food, water, medical aid, and shelter. Demand forecasting estimates the required amount and type of relief goods based on population impact and disaster severity. Relief goods logistics manages the transportation, storage, and distribution of supplies for timely delivery. Makeshift recovery planning focuses on short-term efforts, such as damage assessment, debris removal, and temporary housing.

-

Recovery involves planning for the long-term reconstruction of affected communities. It includes repairing infrastructure, revitalizing the economy, and providing psychological support for survivors. Damage prevention focuses on minimizing future damage from similar disasters. Measures may include strengthening infrastructure, implementing early warning systems, and relocating vulnerable communities.

To manage the disaster management process, governments of most countries operate special organizations to respond to massive natural disasters. These systems focus on management-level tasks such as administrative control, resource securement, and disaster information management. However, communication problems between relief organizations and victims in the disaster scenes often occur, and they cause various problems. Serious delays in the disaster response of Haiti and Tohoku are examples of communication problems in last-mile logistics for relief logistics. The communication problems in relief logistics are connected to the uncertainties at the disaster scene in the response stage. Because of the damage to the communication infrastructure, information gathering is interrupted; the characteristics of relief demand and natural disasters also make demand forecasting difficult, and pre-made logistics plans are not executed as planned usually. Therefore, an emergency logistics system built for the response stage must consider the harsh disaster environment.

The last mile refers to the final stage in logistics, where goods are transported from a hub to the end consumer. The problem addressed in this study is the last-mile logistics of delivering relief supplies to the end user, the evacuees, in a disaster-damaged environment. This study proposes an ELS (emergency logistics system) that deals with the VRP (vehicle routing problem) and facility management problems for efficient last mile logistics in the response stage. The last mile problem is challenging enough on its own, but the characteristics of the disaster environment make it even more complex. To overcome communication problems and uncertainties, a distributed vehicle routing algorithm (DVRA) and a 2-phase facility planning algorithm are suggested. Because the purpose of the ELS is to save victims in damaged areas, the most important goal in the planning is to satisfy the deadline of demands and enhance the time effectiveness rather than cost savings. The ELS presented in this study aims to execute effective logistics in the damaged areas by natural disasters.

In the DVRA, each relief vehicle in the disaster scene gathers information and makes the initial route, and then, each vehicle coordinates the initial routes to complete the final route plan. Using the DVRA, demand information can be gathered directly, and it is expected to resolve the difficulties of information transmission by decreasing communication requests. In facility planning, a 2-phase facility planning algorithm is suggested, which makes plans for the mitigation and preparedness phase. With the suggested facility algorithm, it is possible to make a flexible facility installation considering the characteristics of the disasters.

Literature review

Emergency logistics is a critical research area, as the ability to execute effective emergency logistics during disasters directly impacts the survival of victims. Despite its significance, the body of literature on this topic remains relatively limited. Existing studies generally address two main types of problems: operational problems and vehicle routing and facility management problems. Operational problems encompass key decision-making processes, information gathering, and damage assessment. These challenges require robust models to address uncertainties and improve response efficiency. Chen et al. (2019) proposed a risk propagation model to evaluate risks associated with facilities, vehicles, and relief goods in emergency logistics systems1. Using a network-based approach, their model integrates disaster information and network characteristics to propagate risks effectively. The model’s performance was validated under ideal data-gathering conditions, highlighting its potential in theoretical applications.

Similarly, Sheikholeslami and Zarrinpoor (2024) introduced a robust logistics model tailored for epidemics, addressing factors such as demand uncertainty, quarantine zones, and perishability of goods2. Their model, validated through a COVID-19 case study, demonstrates the importance of adapting operational strategies to dynamic and challenging scenarios. In the context of general logistics, Lee and Roh (2023) explored how digitalization capabilities, combined with open innovation and coopetition strategies, influence sustainable performance in business ecosystems3. Their findings highlight the role of robust digitalization in fostering collaboration and improving sustainability outcomes. Such innovations in general logistics provide valuable insights that could influence emergency logistics by introducing sustainable practices and digital strategies to enhance resilience and adaptability during crises. Zhang et al. (2021) analyzed factors influencing public health emergency logistics and proposed a back-propagation neural network model to evaluate system capability4. This innovative approach offers insights into facility planning, applicable to both public health and general disaster logistics scenarios.

Schumann et al. (2018) reviewed methods for estimating damaged areas and relief demands based on historic records, social media data, satellite imagery, and simulations5. Their satellite-based damage assessment method proved practical for real disaster scenarios, providing a benchmark for reliability processes in logistics systems. Sabbaghtorkan et al. (2020) reviewed prepositioning strategies for assets and supplies in emergency logistics6. They identified research gaps in uncertainty management, risk mitigation, and timing of execution, emphasizing the importance of addressing uncertainties in disaster response systems. Abdel-Basset et al. (2020) proposed a framework comparing various multi-criteria decision-making methods such as AHP, VICTOR, and Topsis7. Their study highlights the role of policy decisions in disaster response systems, including setting reliability levels and allocating budgets. Diehlmann et al. (2021) applied game theory to model collaborations between government and non-government organizations in humanitarian aid8. Their cooperative model maximizes organizational profit while maintaining humanitarian goals.

Lim et al. (2022) introduced a comprehensive decision-making system for evacuation planning during sudden disasters like volcanic eruptions9. The system considered diverse factors, including evacuation modes, timing, and destination types, and was validated using records from the 2020 Taal Volcanic eruption. Wang (2021) used a fuzzy algorithm to optimize disaster resource allocation, minimizing delivery time and distribution cost10. A case study on the Wuhan earthquake validated the model’s effectiveness, offering insights into resource pre-allocation strategies. Ma et al. (2019) proposed a mixed integer programming model for blood distribution, incorporating compatible substitutes11. Their study, validated through the Sichuan earthquake case, provided a solution to resource allocation challenges during disasters.

Efficient vehicle routing and facility management are vital to the execution of relief logistics. Researchers have explored diverse methodologies to address these challenges. Zhang et al. (2019) proposed a three-stage stochastic model integrating facility location, vehicle routing, and secondary disaster analysis12. This model offers a practical approach to infrastructure reliability and disaster response. Ergün et al. (2021) applied game theory to solve decision-making problems such as route allocation, modal selection, and transportation order13. Their model demonstrated effectiveness in earthquake scenarios using real disaster data. Feng et al. (2019) suggested a multi-objective optimization model for selecting rescue facilities14. Their model, focused on minimizing cost and maximizing speed, was validated through simulations and sensitivity analyses. Huang and Song (2018) analyzed the effects of unexpected events on relief demand and travel times15. They developed a vehicle routing algorithm based on a genetic algorithm, addressing uncertainties effectively.

A state-space-time network-based model was introduced to solve vehicle routing problems under collaborative alliances3,16,17,18. Their two-stage heuristic method optimized cost and response speed. Chen et al. (2020) focused on vehicle allocation during disease outbreaks like COVID-19, proposing an integer programming model with sustainability objectives19. While distinct in context, their approach provided valuable insights into algorithmic design. Chu and Chen (2021) devised a hybrid algorithm combining firefly and genetic algorithms for facility location-allocation problems20. Their three-level emergency logistics model highlighted the benefits of integrating multiple algorithms. Pu and Zhao (2024) extended this research by addressing vehicle three-dimensional loading constraints in post-earthquake emergency logistics21. Their multi-objective model optimizes distribution hub locations, material distribution strategies, and precise loading plans, aiming to reduce societal expenses and mitigate risks. Zhang (2023) introduced an optimization approach for emergency logistics using a genetic algorithm with a monarch scheme, facilitated by a cloud platform22. This model significantly reduces costs and improves distribution times, as validated by experimental data. Zhang et al. (2023) presented a two-stage stochastic programming model for location-inventory-routing optimization in emergency logistics23. By considering multiple reliability factors under uncertainty, their model enhances rescue efficiency and reduces disaster losses, contributing to better overall disaster response strategies. Recent research has provided new solutions to the challenges of last-mile logistics in disaster scenarios. Faiz et al. (2022) introduced a robust optimization framework for a two-echelon vehicle and UAV routing system in post-disaster operations24. Their model addresses demand uncertainty and infrastructure failures, validated using data from Hurricane Maria.

Siddig and Song (2022) proposed a multi-stage stochastic programming method for adaptive disaster relief logistics planning25. This model dynamically adjusts logistics decisions as disaster characteristics evolve, improving responsiveness and cost efficiency. Clemente et al. (2022) focused on relief distribution optimization by identifying optimal distribution facility locations and assigning tasks to delivery fleets based on regional road networks26. Their works highlight the critical role of last-mile logistics in ensuring timely and effective disaster response. These studies have limitations as they primarily utilize existing techniques like stochastic programming to address the challenges of last-mile logistics. To overcome these limitations, this study explores alternative methods such as modifying information collection points (DVRA) and adjusting response timings (2-phase facility planning) to better manage information uncertainty and improve operational efficiency. A recurring limitation in the reviewed studies is the assumption of readily available and accurate data for decision-making. In real disaster scenarios, public infrastructure is often compromised, and situational changes render collected data obsolete. This highlights the need for seamless and accurate information collection by developing systems that adapt to dynamic disaster conditions and prioritize real-time data accuracy, which is very difficult to achieve. For this reason, our study suggests ELS, which introduces changes in the timing of the information collection, and plan generation to improve the speed and accuracy of the information and route plan. Lee et al. (2023) examined consumer intentions to use electric vehicles (EVs) using value-belief-norm theory and planned behavior theory27. It found that altruistic and biospheric values positively influence awareness of consequences, while egoistic values have a negative effect. The study also confirmed the roles of attitude toward behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control in linking pro-environmental personal norms to behavioral intention. The findings offer theoretical insights and practical implications for increasing EV adoption. Lee et al. (2024) studied the role of environmental, social, and governance strategy (ESGS) in mediating the relationship between institutional pressures and triple bottom-line performance (TBLP)18. The research, based on data from China’s retail and transportation sectors, found that ESGS partially mediates the impact of institutional pressures on TBLP, while digitalization capability moderates this relationship. The study suggests that organizations can strategically leverage ESG initiatives to improve TBLP by integrating institutional theory and dynamic capability perspectives.

This study is organized into six sections. In “Introduction” section provides the introduction. In “Literature review” section reviews relevant literature. In “Problem definition” section defines the problem addressed in this study. In “Suggested solution procedure” section introduces the DVRA and facility planning algorithms. In “Experiment” section presents the simulation settings and experimental results. Finally, “Conclusion” section concludes the study with remarks.

Problem definition

This study tried to solve the VRP (vehicle routing problem) and facility management problems with the suggested ELS. The facility management problem deals with the facility location and scale planning in the mitigation and preparedness phase and the facility resource allocation problem in the response phase. The VRP is related to the vehicle route, resource distribution, and replenishment planning in the response phase. The objective of the distributed ELS is to save the victims and to take care of refugees. It tries to maximize the number of satisfied demands within the deadline.

Assumptions

-

Demand Types: Three types of demands are considered: evacuation, medicine, and daily necessities. Medicine demands are smaller but urgent, while daily necessities involve larger volumes and longer time frames. The evacuation demand is a demand for evacuees’ shelters during a disaster; it is considered only in the facility planning.

-

Information Availability: Information on demands is collected through headquarters, relief facilities, and vehicles operating on-site. A portion of the demands remains unrecognized by the headquarters, with some of these unrecognized demands subsequently identified by on-site vehicles. The process of demand recognition is subject to delays, and the exchange of information is often prone to errors or latency.

-

Vehicle Assumptions: Identical vehicles, procured during the mitigation phase, are pre-allocated before disasters to facilitate the delivery of relief supplies.

-

Facility Types: We assume two types of facilities: fixed facilities, constructed during peacetime, and temporary facilities, established post-forecast. Fixed facilities are presumed to have lower operational costs and greater ease of reservation.

-

Environment: Emergency logistics systems (ELS) operate in densely populated urban areas where disasters may disrupt traffic networks. Reliability reflects the probability of roads and facilities remaining functional after disasters.

-

Disaster Response Policies: Fixed budgets are assumed for facilities, with distribution ratios and reliability thresholds determined by policy.

-

Risk Assessment: Infrastructure risks (e.g., bridges, slopes) influence road and facility reliability. Proximity to vulnerable infrastructure decreases functionality. Equation (1) shows the reliability calculation method using the results of the assessment. Table 1 outlines the vulnerable infrastructures and associated parameters considered in the reliability calculation. It is assumed that the vulnerability level and influence radius differ depending on the type of infrastructure. Equation (1) shows the reliability calculation method using the results of the assessment.

$$R = \mathop {\min }\limits_{{e \in E}} \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}l} {d_{e} \le l_{e} {:}1 - \frac{{1 - r_{e} }}{{e^{{4d_{e} /l_{e} }} }}} \hfill \\ {d_{e}> l_{e} {:}1} \hfill \\ \end{array} } \right.$$(1)

Mixed integer programming (MIP)

To define the emergency logistics problem related to the facility and vehicle management problem, the following MIP is defined (Table 2).

Equation (2) serves as the objective function, aiming to maximize the number of demands met within the deadline. Equations (3) to (7) define constraints related to facility setup. Equation (3) represents the resource dynamics at a facility. Equation (4) ensures that the resource amount at a facility does not exceed its capacity. Equation (5) establishes a budgetary constraint on the total installation cost for facilities. Equation (6) limits the scale of facilities during setup. Equation (7) ensures consistency between the decision variables for facility installation and facility scale.

Equations (8) to (14) govern vehicle routing. Equation (8) ensures each vehicle selects only one route. Equations (9) and (10) define constraints on the departure and termination points of vehicle routes. Equation (11) prevents vehicles from remaining stationary at a single node. Equation (12) ensures continuity in the vehicle’s route to reach the endpoint. Equation (13) sets the initial departure time to zero. Equation (14) calculates departure times at each node.

Equations (15) to (21) address resource possession and utilization. Equation (15) calculates the initial resource quantity at the departure point. Equation (16) enforces constraints on resource possession along consecutive routes. Equation (17) ensures that the total resource quantity does not exceed the vehicle’s carrying capacity. Equation (18) restricts resource usage to demand locations along the route. Equation (19) limits resource replenishment to facilities along the route. Equation (20) ensures the total utilized resource matches the demand requirements. Equation (21) ensures that resource usage aligns with the vehicle’s resource possession.

Equations (22) to (25) evaluate deadlines. Equation (22) determines whether vehicle visits occur within the specified deadlines. Equations (23) and (24) assess the resource quantities delivered to meet demands within the deadline. Equation (25) evaluates whether the demand is fully satisfied. Equations (26) and (27) impose non-negativity constraints on the decision variables.

The definition includes facility and vehicle management problems that cover the route of the vehicle, the relief goods used and replenishment plan, the result of the resource delivery for each demand, and the relief resources stocked at every facility. The objective function of the plan is to maximize the number of demands that meet the deadline. Because this problem contains the multiplication of variables, this problem does not satisfy Positive Semi-Definite (PSD) condition, which is critical for ensuring convexity, and fast solving. PSD measures the effectiveness of resource allocation in disaster relief by calculating the proportion of demands met on time relative to the total demands. Therefore, it is impossible to find an optimal solution within a reasonable computation time. To overcome the characteristics of this problem and the uncertainties of a disaster scene, this study applied a meta-heuristic algorithm and distributed approach.

Suggested solution procedure

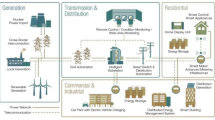

Emergency logistics system

In this study, we focused on the relief facility management problem and the vehicle route problem. The relief facility management problem covers the process of determining the location and scale of the facility and replenishing relief resources. The vehicle plan covers plans for the allocation of relief vehicles in peacetime and a last-mile vehicle route plan to deliver and supplement relief supplies. However, there are communication and information uncertainty problems in these emergency logistics. Thus, the DVRA (the distributed vehicle routing algorithm) and 2-phase relief facility planning algorithm are applied to overcome these problems. In a 2-phase planning algorithm, the size and location of the facilities are planned in the mitigation and preparedness stage. In the mitigation stage, the facility plan is built based on historic disaster data and sufficient resources and time. After a disaster is forecasted, the plan is revised based on more accurate disaster information and resource availability by adding temporary facilities. In the DVRA, each vehicle makes its route plan based on the relief demand acquired from HQ and disaster scene and facility planning results and then revises the original plans by removing redundant visits and taking uncovered demands through communication among the vehicles. With these processes, the logistics system works well against the uncertainty in the field information compared to a centralized system in which all decision problems are solved by a central headquarters. To support and accelerate information collection by vehicles, automated information collecting tools are installed. These tools contain various sensors to recognize the status of a disaster, the status of the traffic networks, and information for new demands. Sensors are packed in an additional communication box described in Fig. 3. Table 3 summarizes the collection and application of the information from each sensor.

Distributed approach for the vehicle plan

In general logistics systems, information collection, logistics planning, and plan execution are based on efficient information exchange. In a disaster scene, the vulnerability in infrastructures, such as the communication relay center and base center, may cause uncertainty in the information exchange, which can lead to reduced functionality of the logistics system.

To overcome this potential limitation, a distributed approach to planning is suggested. In this distributed approach, each vehicle makes its route by itself and arranges the route information by communicating with the other vehicles using military standard level telecommunication measures. The entire process is described in Fig. 4, and these processes are repeated every 30 min until the end of the disaster. In this approach, it is possible to decrease the number of information exchanges from information collection to plan generation and execution. Moreover, because each vehicle makes its route, the computation complexity and time to plan are decreased. Additionally, it is possible to be flexible to unexpected events and accidents in the traffic network.

Route planning algorithm

The genetic algorithm (GA), one of the most well-known meta-heuristic algorithms, is applied to make a vehicle plan that consists of a routing plan and a resource plan. The parameters of the genetic algorithm were determined through pilot experiments. Probabilistic parameters related to operators and chromosome initialization were selected based on the combination that yielded the best results during the pilot tests. Parameters of the total length of generations were set by increasing the average length of the point at which improvement rates significantly decreased during the pilot experiments by 25%. Due to the capacity limitations of a vehicle, it would have to visit facilities to replenish relief resources. Thus, a chromosome could represent a visiting sequence of demand areas and facilities and volumes of relief resources for delivery/replenishment. For this requirement, two candidates of chromosome structure are described in Fig. 5. In the Fig. 5, the node number with one digit represents the demand area, and two digits represent the facility node. (A) contains information about the route, resource delivery, and resource replenishment. It does not need an additional process to complete a vehicle plan, but it often generates infeasible vehicle plans through GA operations. Compared to (A), (B) contains route information about visiting demand areas only. Its simple structure prevents errors from the result of the GA operation. However, it requires an additional process to add resource plans such as delivery and replenishment. In this study, structure (B) is selected to avoid an infeasibility resolving process.

To complete the resource plan with (B), the time to visit facility nodes and resource type and volume to replenish should be determined. This problem belongs to the combinatorial optimization problem and can be formulated in MIP which requires a large computational time; thus, a heuristic algorithm, as shown in Fig. 6, is applied in this study. As shown in Fig. 6, at first, the algorithm finds the first node where relief resource shortage is expected under the assumption of sequential visits on the route. Next, the required travel times to visit a facility node for all preceding nodes are calculated. Finally, the node for which the travel time from it results in minimum deadline violations for a subsequent node is selected as the facility visiting node. And the tie-breaking rule is the minimum travel time. The replenishing amount and type of resources follow the type and amounts of resources lacking on the following visiting nodes. If the size of the demand is too large to finish it with a single visit, multiple round-trip routes between the facility and demand is considered.

The objective of the plan is to maximize the number of demands satisfying the deadline. Evaluation of the chromosome also focuses on maximizing the number of demands satisfying the deadline, as described in Eq. (28). i is the index of chromosome, and S(i) and U(i) are the number of demands which satisfied deadline and not satisfied deadline

Based on the fitness value, the probability of selecting a chromosome for a crossover operator is calculated as Eq. (29). Here, fi means the probability; ci, cb, and cw are the fitness values of chromosome i, the best chromosome, and the worst chromosome, respectively.

To generate the initial population, two methods are applied: a heuristic method and a randomized method. As shown in Fig. 7, in the heuristic method, the urgency index for each node is calculated by taking the reciprocal of the deadline. Additionally, the probability is calculated by normalizing the urgency index. Finally, a visiting sequence for a chromosome is randomly generated based on this probability. A node with high probability can be easily selected at the front positions. In the randomized method, the visiting sequence is generated randomly without considering deadlines.

These methods are expected to contribute to enhancing the performance and diversity of chromosomes. 20% of the initial population is generated by the heuristic method, and the remaining 80% is generated by the randomized method. An order-based crossover is applied as a crossover operator. In a mutation, two arbitrarily selected nodes in a chromosome are exchanged. The cutting points in the crossover and mutation are selected randomly. The probability of mutation is set to 10% initially and is decreased gradually as described in Eq. (30). Here, T means the maximum number of generations; t means the number of past generations, and b is a parameter to adjust for the decreasing speed.

As the generations increase, it becomes more difficult to find better solutions with the GA. Therefore, if the GA fails to find a more improved solution within a certain number of consecutive generations, the algorithm terminates. The number of generations without progress is limited to 100. In addition, if the number of generations exceeds 1000, the algorithm terminates. These parameters are set based on the results of a pilot study.

Route adjustments process

After the route plans of the individual vehicles are determined, the mutual adjustment process is executed to adjust route plans. As shown in Fig. 8, it is executed by every vehicle through communication between themselves. The goal of the adjustment is to remove redundant visits from the route plans of individual vehicles for relief demand, and it is executed through pairwise communications between nearby vehicles. A detailed process to find a communicating vehicle is described in Fig. 9. The communication request is made by broadcasting its location and route plan to nearby vehicles, and the communication target is limited to vehicles having redundant visits in its route plan.

To select a vehicle to remove a redundant visit from its route, the increasing quantity of deadline satisfaction demands by removing the visit is considered in pairwise communication. This election process is repeated until every redundant visit is removed. After this process is finished, each vehicle starts its vehicle plan and transfers the completed plan to HQ, and HQ gathers every plan and summarizes them to find any uncovered demands that should be considered in the next plan.

Facility planning and management

The facility can be divided into two types: fixed and temporary. A fixed facility is a facility that has been constructed or re-installed in ordinary times, that is, before a disaster warning and a temporary facility represents a facility that will be installed after a disaster warning. As mentioned in “Mixed integer programming (MIP)” section, facility planning for both types includes the process of determining locations (or nodes) and the scale of the facilities and filling them with relief resources that would be required from demand nodes in a disaster scene. For the 2 types of facilities, a 2-phase facility planning algorithm is proposed: the 1st phase is for fixed facilities, and the other one is for temporary facilities.

To make a facility plan, reliability information and demand information are needed. The demand information represents which nodes require which and how many relief resources. It is hardly possible to accurately predict the disaster occurrences within a short timeframe. Therefore, when apply the 1-phase planning algorithm first-stage plan, the statistical forecast data based on historical disaster records must be applied to planning. Assuming that the probability of damage occurrence is identical across all areas, a simplified comparison of damage coverage between the 1-phase and 2-phase planning algorithm is second-stage plans is presented in Fig. 10. In this comparison, the temporary facility installation costs in the second phase are assumed as 1.3 times, 1.5 times, and 2 times higher than those in the first-stage plan. In the result of simple comparison, while 2-phase algorithm covers 100% of damage, 1-phase algorithm only covers 84.4% of damage. Even with a cost increase of up to 2.3 times, the coverage rate achieves 89.2%, surpassing the performance of the 1-phase planning algorithm. Given the characteristics of the 2-phase planning approach, which enables adjustments following disaster forecasts, it is anticipated to demonstrate superior performance compared to the 1-phase planning algorithm.

This information is derived from the disaster influence factor (DIF) for a disaster. DIF means a set of elements that characterize it and is retrieved from the records of past disasters. It includes probability, reliability, affected areas, and magnitude parameters. The probability means the occurrence possibility of a disaster; the reliability represents the reliability information in a disaster; the affected areas represent a set of nodes damaged by it; the magnitude means the intensity of it, and the distribution parameters represent the parameters used to define a probability distribution function of relief demands for relief resources in the affected areas. Here, it is assumed that the affected areas can be recognized with the coordinates of center and distance. Prior to the facility planning, the DIFs for all disaster types should be organized, and policies for facility planning should be determined. Three policies are applied, which are the policy response limit (PRL), budget limit, and budget distribution between fixed and temporary facilities. The PRL includes the lower bound for the reliability of facilities and road networks between the demands and facilities. And the budget distribution policy determines the allocation ratio of the total facility budget to fixed and temporary facility installations.

2-Phase facility planning

In the 1st phase of the proposed algorithm, the fixed facilities to be newly constructed or re-installed are selected from existing and new candidates of fixed facilities by considering the DIFs and constraints due to budget limits and the PRL. As mentioned above, this phase is executed in ordinary times and applies a GA to be explained in the next section. The entire DIFs for all disaster types are used to generate the demand information and to evaluate a solution that represents at which node the facility locates and in which kinds and how many relief resources are filled. In the next phase, the temporary facilities to be newly installed are selected from candidates for temporary facilities by considering fixed facilities selected in the 1st phase with similar restrictions. Instead of the entire DIFs, only the DIF for the same type of disaster forecasted is used. Additionally, the initial positions of the relief vehicles are also determined in this phase. The vehicles are initially allocated to the facilities in proportion to the ratio of their holding to the demand volumes that would be covered by them. This phase is executed after a disaster alert and applies the same GA used in 1st phase. The entire facility planning algorithm follows the process shown in Fig. 10.

With the completed facility plan, vehicles to deliver relief resources are allocated. The number of allocated vehicles is proportional to the amount of forecasted demand, and the amount of demands is forecasted based on the DIF and demand allocation algorithm.

Genetic algorithm for facility planning

As described in Fig. 11, to represent the information about the location of the facilities and the volume of resources to be filled, a chromosome in a 2-dimensional structure is adopted. The row represents the resource types, the column represents nodes where a facility is installed, and the number in the cell (i, j) represents the volume of resource type i that is filled in facility j.

In chromosome initialization, the capacity of a facility to be installed is assigned randomly not more than twice the physical scale of each node to increase the diversity of the solution pool. To select a node to install a facility, divide the entire initial population into three groups, and then assign each group a probability of 0.3, 0.5, and 0.7. Next, whether a facility is installed on a node belonging to a particular chromosome in each group is determined by the probability assigned. The Crossover, mutation, and fixing operators are defined for the 2-dimensional chromosome. In the crossover operation, the block uniform crossover method is applied as described in Fig. 12. The number of cuts for the crossover operator is set to the maximum of a value obtained by dividing the length by 4 and then rounding up and 1 for each dimension. In the mutation operation, a node randomly is selected, and its volume is modified, and this process is repeated for all resource types in a selected chromosome.

The result of the crossover and mutation operator sometimes violates the physical scale constraint of the node or the overall budget constraint, and it represents an infeasible facility plan. The chromosome that violates these constraints needs to be corrected to be a feasible plan through an infeasibility resolution process described in Fig. 13.

The probabilities applied to parent selection in the crossover, the mutation, and infeasibility resolution are calculated as shown in Eq. (5). As shown in (a), basically, the probability of parent selection is proportional to the evaluation value of a chromosome, but a balancing concept that prevents the probability of selecting chromosomes with a low evaluation value from converging to zero is included. In this equation, cb, cw, and ci represent the selection probability of the best chromosome, worst chromosome, and chromosome i, respectively. And fi represents the selection probability of chromosome I. The probability for mutation, as shown in (b), is set to be high to increase the diversity in the early generations and gradually is decreased to maintain the quality in the later generations. Here, t, T, b, and ptm represent the current generation index, maximum generation, reduction factor, and mutation probability in the t-th generation. And the probability for infeasibility resolution ptf is calculated similarly as shown in (c).

The evaluation of a chromosome is calculated from the proportion of relief demands that satisfy the deadline constraint. At first, as mentioned in “Results” section, generate the relief demands from a randomly selected DIF and then calculate the proportion of relief demands satisfied based on the rule that the nearest facility covers the corresponding demand with volumes and reliability constraints. Repeat these steps 100 times, and obtain an average as the evaluation value. As mentioned in “Results” section, all DIFs are used in fixed facility planning and only the DIF for the same type of disaster alerted is used in temporary facility planning. The detailed process of the evaluation is described in Fig. 14.

The population size for facility planning is set at 1,000. And the GA terminates when the number of generations reaches 1,000 or there is no improvement for 100 consecutive generations.

Operating facilities in disaster scene

Even though a facility plan is made based on not only records of past disasters but also on information about ongoing disasters, many problems can arise at the time of an actual operation due to the gap between forecasted data and actual data. To reduce this gap, facilities must gather and share much information, such as reliability, relief demand, the status of other facilities, etc., using all available channels and relief vehicles. Individual facilities must determine the expected relief resource needs more accurately using the gathered information and try to balance the quantity held with the quantity to be used in cooperation with sources of relief resources including other facilities. A simple heuristic algorithm is suggested to support exchanging insufficient resources and surplus resources between facilities and replenishing from outside shown in Fig. 15. Based on the results, the facility operating plan needs to be modified and reported to HQ to ask for additional resources and help from the outside.

Experiment

Experimental environment

The simulation experiment was conducted based on past disaster records for target administrative districts defined based on similar characteristics of the major administrative districts (e.g., Gu) with a high population density in Seoul, South Korea. Three typical types of disaster, such as flood by heavy rain, flood and strong wind by typhoon, and collapse by earthquakes, were considered. For each disaster, two levels of magnitude, ‘Weak’ and ‘Strong’, were considered, and the directly affected area (DAA) was represented by a circle with the center point and radius. The area except for the DAA in the target district was classified as an indirectly affected area (IAA). Relief demands may occur in both the DAA and IDA with different ratios. Moreover, to reflect the characteristic of an earthquake which is very difficult to forecast, a temporary facility installation starts after the disaster starts and finishes after 30 min.

The target district was divided into 40 same-sized small administrative districts (SADs; e.g., Dong). It was assumed that a SAD has only one candidate place (expressed as a ‘node’ hereafter) for the facility installation and has a randomly determined number of nodes for shelters [1, 5]. The locations of those nodes were randomly selected within the SAD.

Each SAD is divided into an exclusive node area (NAs) based on the locations of the given nodes, and the victims in the NA are evacuated to that node and become evacuees. The shelter node provides an evacuation space and relief resources for evacuees affected by the disaster in the corresponding NA, and the facility node provides storage space for the relief resources. The evacuees in shelters are assumed as the source of all relief demand, and the proposed ELS focuses on relief demands generated by evacuees in the shelter.

Each SAD is divided into an exclusive node area (NAs) based on the locations of the given nodes, and the victims in the NA are evacuated to that node. The shelter node provides an evacuation space and relief resources for victims affected by the disaster in the corresponding NA, and the facility node provides storage space for the relief resources, additionally. For the simulation experiment, it is necessary to determine whether a NA is included in the DAA, whether relief demands occur, and the number of victims for each NA. Whether a NA is included in the DAA can be checked by the location of the corresponding node. The center point of the disaster is determined at random, and the radius is described in Table 4. Whether relief demands occur in a NA is defined stochastically by the type of disaster, its magnitude, and whether it was included in the DAA shown in the column “Relief demand occurrence probability” in Table 4. For example, the probability of relief demand occurrence in a NA belonging to the DAA in a typhoon situation of “Wea” magnitude is 35%. The number of victims is calculated by multiplying the population number of a NA by a designated percentage, which is defined based on the type of disaster, its magnitude, and whether it is included in the DAA, as shown in the column ‘ratio of victims’ in Table 4. The population in a NA is derived from that in the target district. To verify the performance according to the population density, three types of sizes were considered for the population number of the target district: Small, Medium, and Large. From the information on the population of major cities in South Korea, Small, Medium, and Large were defined as ranges of [217,836 ~ 500,435], [500,436 ~ 783,035], and [783,036 ~ 1,062,636], respectively. Based on these, the population number of a NA is determined randomly from the intervals of [217,836/TN ~ 500,435/TN], [500,436/TN ~ 783,035/TN], and [783,036/TN ~ 1,062,636/TN] for Small, Medium, and Large, respectively. Here, TN is the total number of NAs in a target district, that is, the total number of NAs included in 40 SADs in the target district.

Meanwhile, victims of a disaster cannot be evacuated to a facility or shelter node at once but gradually evacuated. To take this into account, the concept of evacuation within a certain time interval was introduced. For a NA classified as a relief demand occurring node, the number of people evacuated to facility or shelter nodes increases every 30 min by the designated ratio of the number of people who could not be evacuated until that time. The designated ratio is presented in the column ‘Ratio of evacuees’ in Table 4.

The magnitude of the disaster also affects the recognition of demands. Compared to the “Weak” magnitude, the “Strong” makes relief demands more difficult to be recognized. In the simulation, [5% and 15%] and [15% and 25%] of the relief demands for the “Weak” and “Strong” magnitudes can only be recognized by the vehicles, not by HQ. Three types of relief demands that come from the evacuees in the facility and shelter node are considered: Daily Necessity, Grocery, and Medicine demands. The Daily Necessity and Medicine demands are generated only once, but the Grocery demand is generated 3 times at eight-hour intervals in a day for the entire experiment period. The amounts of Daily Necessity and Grocery demands are equal to the number of evacuees increased at the time of generation, but the Medicine demand is determined as the ratio of the number of evacuees, and three ratios were considered: 10%, 20%, and 30%.

A deadline is set for all demands, where the deadline represents the time range in which the corresponding relied resource can be used effectively without being useless. The deadline of the Daily necessity and Grocery demands and that of the Grocery demand was determined randomly in the intervals of [6.75,60] and [2.09,13.34], respectively. These intervals are defined by the statistics of emergency calls (e.g., 911 calls) in South Korea and represented in minutes. The policy decisions presented in this study include the budget limit, the allocation of budgets for fixed and temporary facilities, and the PRL. In this study, two budget limits of 5,000 M and 3,000 M KRW were applied, and three types of PRL of 0.3, 0.5, and 0.7 were applied. In the case of budget allocation, only one case of 7:3 was applied. As mentioned earlier, the damage caused by disasters often disables road networks. This characteristic is also applied in the simulation environments; the roads in the network become disabled by chance with the same probabilities in Sect. 3.1.1. Two types of experiments were conducted to evaluate the performances of the suggested algorithms: the vehicle routing algorithm and the facility planning algorithm as explained in the previous section. For these experiments, not only the parameters explained above but also the parameters for the physical environment, including vehicle speed, etc., are summarized in Table 5.

As described above in Table 5, factors and sub-factors such as the number of residents (NR), MDP, type of disaster (TD), and magnitude of disaster (MD) were considered in the experiments for the DVRA, and 2 more factors budget limit (BL) and reliability limit (RL) were additionally considered in the experiments for the ELS. For each experimental problem, 100 iterations were conducted. .NET frameworks were applied to realize the suggested algorithms, and those were executed on a computer equipped with an Intel® Core™ i5-4690 Processor 3.50 GHz and 16 GB RAM.

Results

The experimental results for the vehicle routing algorithm are summarized Table 6 and analyzed focusing.

on the average percentage of satisfied demands (APSD), average computation time (ACT), average movement time (AMT), and average loading/unloading time (ALUT) where the ND and AAD represent the number of demands and average amount of demand, respectively. First, the statistical verification using ANOVA shows that all factors (including sub-factors) have an effect on the APSD with a p-value less than 0.05. Overall, about 70.7% of the demand is satisfied by the DVRA, which reaches about 95% of an optimal solution. The effectiveness of the adjustment process was demonstrated through a comparison of APSD before and after adjustment. Prior to the adjustment, the APSD was 63.2%, while it improved to 70.2% after the adjustment, indicating an average improvement of 7.52%. This represents an enhancement exceeding 10%, suggesting that the adjustment process plays a significant role in improving the performance of logistics networks under conditions of incomplete demand information collection and transmission.

As shown in Fig. 16a, the APSD seems to be most affected by TD, which is relatively lower in earthquakes and higher in heavy rainfall, and slightly higher in “Weak” than “Strong” in MD. The reason is that earthquakes usually affect a relatively wide range, resulting in a higher ND compared to a limited NSD. For each type of disaster, as the NR increases, the ND increases relatively slightly, but there is little variation in the APSD shown in Fig. 16b. The increment in NR can cause a small increment in the ND due to the occurrence of victims on new nodes and cause a proportional increment in the AAD on existing nodes. Meanwhile, the time requirement for traveling among nodes including facilities is greater than the time of lading/unloading resources, and vehicles try to increase the NSD (number of satisfied demands) by intensively delivering resources to nearby nodes. This result is confirmed in Table 6 showing that the percentage of AULT increases from 33.1 to 45.8% as the NR increases.

From the point that the tendency of the APSD for TD and NR is similar in the optimal solutions, the robustness of the DVRA can be confirmed. Moreover, the DVRA takes about 25 s in vehicle route planning which remains around 6.7% of the optimal solution, so the adaptability of the DVRA for emergency logistics systems can be confirmed, too. The experimental results for the facility planning algorithm are summarized Table 7.

The experimental results were evaluated based on several metrics, including the ratio of the average and maximum allocation distances between demand points and facilities (Distance Ratio), the ratio of demand satisfied its deadline (Allocated Demand Ratio), the amount of resources used for allocation (Allocated Resources), budget utilization, and computation time. The proposed 2-phase facility planning algorithm demonstrated stable performance across various disaster scenarios. This indicates that the algorithm can reliably satisfy most demands, regardless of the type and circumstances of the disaster.

In cases of localized disasters, such as heavy rainfall with relatively lower demand volumes, the algorithm achieved higher fulfillment rates and shorter allocation distances. Conversely, for large-scale disasters like earthquakes, which generate widespread and high demand, the results showed lower values in both distance ratio and allocated demand ratio. For typhoons, which exhibit intermediate characteristics, the algorithm produced moderate results between these two extremes.

In terms of budget utilization, an increase in allocated resources corresponded to higher budget consumption. As for computation time, the total calculation time, including both fixed and temporary facilities, did not exceed 140 s. Moreover, the computation time required for temporary facilities, which demand rapid processing, accounted for less than half of the total computation time. The experimental results for the facility planning algorithm according to budget policy are summarized Tables 8 and 9.

Experimental results under varying budget constraints for fixed and temporary facilities revealed that greater budget flexibility leads to a decrease in the distance ratio and an increase in the allocated demand ratio. While this outcome is expected, the results also indicate that the allocation of budget between fixed and temporary facilities significantly influences performance. When comparing budget plans of [3 billion, 2 billion] and [5 billion, 1 billion] against a baseline plan of [3 billion, 1 billion], the total budget increased by 1 billion and 2 billion, respectively. However, the increase in the allocated demand ratio was less than proportional to the budget increment. This suggests that allocating more budget to temporary facilities may be more efficient than allocating it to fixed facilities. Nevertheless, as temporary facilities are capable of delivering less quantities of relief supplies for the same cost, they cannot address the entire demand independently. Therefore, when applying this model in practice, it is crucial to determine an optimal budget allocation ratio between fixed and temporary facilities to maximize efficiency.

The experimental results for the ELS are summarized in two tables through division and aggregation of the factors due to space limits. Table 10 shows the aggregated results for the same factors in the DVRA, and Table 11 shows the aggregated results for the BL and RL factors, average fleet size (AFS), average cost (AC), average number of facilities (ANF), and average computation time (ACT) of the ELS, and the optimal solution is compared. In the case of the ACT, the optimal setting applied the time required to establish both the vehicles and facilities plan, and the ELS applied the time required to calculate the fixed and temporary facilities plan.

Overall, the mean of the APSD is approximately 74.1%, reaching 92% of the optimal solution, so the proposed ELS seems to show good performance applicable to a disaster scene. Table 10 shows that the trend of the ELS performance variation according to the characteristics of the disasters and residents is similar to that of the DVRA. In the case of an earthquake, which is hard to forecast, the temporary facility installation is delayed, and the overall performance of the ELS under earthquakes significantly decreases compared to other disasters. The AFS, TC, and NF change according to the DT and MD. They are the lowest in heavy rain and the highest in earthquakes. This difference is due to delays in installing temporary facilities and vehicle allocation after a disaster forecast, resulting from differences in predictability between earthquakes and other disasters. Meanwhile, the fact that the obtained AFS is smaller than 60, the given value in the DVRA experiment, but the APSD is similar to that of the DVRA demonstrates that the generated facility plans were efficient in reducing waste in vehicle management.

Table 11 shows the performance of the ELS according to the policies. The performance goes down when the BL decreases. However, overall, despite the smaller fleet size, the performance is better than the singular DVRA. In addition, because the facility planning is done in peacetime, although the ACT reaches 29.90 min, it does not cause any problems in facility planning.

Naturally, as the BL increases, the AC, ANF, and AFS increase, resulting in a higher performance. The ELS approximately consumes 92% of the budget for facility installation and vehicle allocation.

As RL decreases, the NF increases; the reason for this appears to be that the decrease in RL causes an increase in the number of facility candidates. In addition, the increase in NF leads to a decrease in vehicle movement distance due to a decrease in the distances among facilities, and this leads to an increase in the APSD. Overall, the simulation results show that the DVRA and ELS perform well under various natural disasters. Therefore, it seems that the suggested system can be applied to an actual emergency logistics system.

Conclusion

This study suggests a system that covers facility planning, vehicle allocation, and route planning which must be considered during the last mile stage of an emergency logistics system. To solve this problem, this study proposed the ELS which contains a distributed vehicle routing algorithm (DVRA) and a 2-phase facility planning algorithm. In the DVRA, each vehicle makes its own route plan by the genetic algorithm. After that, every vehicle adjusts its route plans through vehicle-to-vehicle communications. In the 2-phase facility planning algorithm, the facility plan, which covers its location and scale, is built in both peacetimes before a disaster alert and response situations with a disaster warning issued. A simulation experiment based on the urban environment of South Korea was conducted to verify the performance of the suggested algorithm. In simulation experiments based on the urban environment of South Korea, the results show that the suggested DVRA works well and robustly in the deadline-based performance evaluation achieving the optimal solution with less computation time under a difficult environment with urgent deadlines and a large number of demands. In the experiment of the ELS, the result shows that its facility plan and vehicle route plan made by the ELS deal well with the relief demands caused by various natural disasters. The results of the whole simulation experiment show that the suggested algorithms are applicable in emergency logistics under actual disasters. In this study, an emergency logistics system that can be applied to various disasters was proposed and verified by a simulation experiment. However, the suggested system has a limitation: the system focused on disasters in South Korea. Future research will cover more natural disasters such as tsunamis, forest fires, pandemics, etc., and man-made disasters such as war and terrorism.

Data availability

The data analysed/generated in the present study will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

17 November 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28586-2

References

Chen, T., Wu, S., Yang, J. & Cong, G. Risk propagation model and its simulation of emergency logistics network based on material reliability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 16(23), 4677. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234677 (2019).

Sheikholeslami, M. & Zarrinpoor, N. Designing a robust logistics model for perishable emergency commodities in an epidemic outbreak using lagrangian relaxation: A case of COVID-19. Ann. Oper. Res. 434(1), 451-459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-024-06116-z (2024).

Lee, M. & Roh, T. Unpacking the sustainable performance in the business ecosystem: Coopetition strategy, open innovation, and digitalization capability. J. Clean. Prod. 412, 137433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137433 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Ding, Q., & Liu, J. B. Performance evaluation of emergency logistics capability for public health emergencies: Perspective of COVID-19. Int. J. Logistics Res. Appl. 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13675567.2021.1914566 (2021).

Schumann, G. J., Brakenridge, G. R., Kettner, A. J., Kashif, R. & Niebuhr, E. Assisting flood disaster response with Earth observation data and products: A critical assessment. Remote Sens. 10(8), 1230. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs10081230 (2018).

Sabbaghtorkan, M., Batta, R. & He, Q. Prepositioning of assets and supplies in disaster operations management: Review and research gap identification. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 284(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2019.06.029 (2020).

Abdel-Basset, M., Mohamed, R., Elhoseny, M. & Chang, V. Evaluation framework for smart disaster response systems in uncertainty environment. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 145, 106941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2020.106941 (2020).

Diehlmann, F. et al. Public-private collaborations in emergency logistics: A framework based on logistical and game-theoretical concepts. Saf. Sci. 141, 105301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105301 (2021).

Lim, H. R., Lim, M., Bernadeth, B. & Rojas, A. W. M. Towards modelling of evacuation behavior and planning for emergency logistics due to the Philippine Taal volcanic eruption in 2020. Nat. Hazards 114(1), 553–581. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-022-05401-z (2022).

Wang, Y. Multiperiod optimal allocation of emergency resources in support of cross-regional disaster sustainable rescue. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 12(3), 394–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-021-00347-5 (2021).

Ma, Z. J., Wang, K. M. & Dai, Y. An emergency blood allocation approach considering blood group compatibility in disaster relief operations. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 10, 74–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-018-0212-7 (2019).

Zhang, J., Liu, H., Yu, G., Ruan, J. & Chan, F. T. A three-stage and multi-objective stochastic programming model to improve the sustainable rescue ability by considering secondary disasters in emergency logistics. Comput. Ind. Eng. 135, 1145–1154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2019.02.003 (2019).

Ergün, S., Usta, P., Alparslan Gök, S. Z. & Weber, G. W. A game theoretical approach to emergency logistics planning in natural disasters. Ann. Oper. Res. 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-021-04099-9 (2021).

Feng, J. R., Gai, W. M. & Li, J. Y. Multi-objective optimization of rescue station selection for emergency logistics management. Saf. Sci. 120, 276–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2019.07.011 (2019).

Huang, X. & Song, L. An emergency logistics distribution routing model for unexpected events. Ann. Oper. Res. 269(1), 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-016-2300-7 (2018).

Wang, Y., Peng, S. & Xu, M. Emergency logistics network design based on space–time resource configuration. Knowl. Based Syst. 223, 107041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2021.107041 (2021).

Kundu, T., Sheu, J. B. & Kuo, H. T. Emergency logistics management—Review and propositions for future research. Transp. Res. E. 164, 102789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2022.102789 (2022).

Lee, M., Pak, A. & Roh, T. The interplay of institutional pressures, digitalization capability, environmental, social, and governance strategy, and triple bottom line performance: A moderated mediation model. Bus. Strategy Environ. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3755 (2024).

Chen, Y., Zheng, W., Li, W. & Huang, Y. The robustness and sustainability of Port logistics systems for emergency supplies from overseas. J. Adv. Transp. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8868533 (2020).

Chu, H. & Chen, Y. A novel hybrid algorithm for multi-objective location-allocation problem in emergency logistics. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/1951161 (2021).

Pu, X. & Zhao, X. Post-Earthquake emergency logistics location-routing optimization considering vehicle three-dimensional loading constraints. Symmetry 16(8), 1080 (2024).

Zhang, B. Optimization of emergency logistics network based on cloud platform. In 2023 International Conference on Applied Intelligence and Sustainable Computing (ICAISC) 1–8. (IEEE, 2023).

Zhang, J., Huang, J., Wang, T. & Zhao, J. Dynamic optimization of emergency logistics for major epidemic considering demand urgency. Systems 11(6), 303 (2023).

Faiz, T. I., Vogiatzis, C., Liu, J. & Noor-E‐Alam, M. A robust optimization framework for two‐echelon vehicle and UAV routing for post‐disaster humanitarian logistics operations. Networks 84(2), 200–219 (2024).

Siddig, M. & Song, Y. Multi-stage stochastic programming methods for adaptive disaster relief logistics planning (2022). arXiv preprint arXiv:2201.10678.

Clemente, J., Suarez, J. J., Demetria, O., Go, P. & Salcedo, D. Some optimization solutions for relief distribution (2022). arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.10491.

Lee, S. S., Kim, Y. & Roh, T. Pro-environmental behavior on electric vehicle use intention: Integrating value-belief-norm theory and theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 418, 138211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.138211 (2023).

Funding

No funding detail.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.H.: Data curation, methodology, software, writing the original draft. H.J.: Methodology, supervision, validation, writing reviews and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article Hanil Jeong was omitted as a corresponding author. Correspondence and requests for materials should also be addressed to hijeong@dju.kr.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, S., Jeong, H. Research on efficient relief logistics planning under massive natural disasters. Sci Rep 15, 11595 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91024-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91024-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Developing a conceptual framework for relief goods distribution during disasters: a multi-method qualitative study

Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition (2025)