Abstract

Urban land subsidence (LS) results in a reduction in ground elevation, compromising infrastructure integrity, disrupting the hydrological cycle, and posing significant risks to economic, demographic, and environmental security. This phenomenon is characterized by a certain degree of latency. In recent years, as Shanghai has undergone rapid urban expansion and high-density development, the issue of LS has become increasingly pronounced. This study employs a multi-criteria decision analysis framework, integrating advanced technologies such as Remote Sensing (RS), Google Earth Engine (GEE), and Small Baseline Subset Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (SBAS-InSAR), to develop a comprehensive evaluation index system comprising fifteen indicators, which consider geological, hydrological, and anthropogenic factors. By applying matrix theory, the study utilizes the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and the Entropy Weight Method (EWM) to integrate subjective and objective weights, thereby determining the comprehensive weight for each indicator. Subsequently, the comprehensive natural disaster risk theory was employed to assess the risk levels across different regions within the study area, which were visualized using ArcGIS. The study area was classified into five risk categories: very low, low, medium, high, and very high, comprising 67.00%, 17.87%, 9.25%, 3.39%, and 2.48% of the total area, respectively. The results closely align with historical cumulative subsidence data and the current LS prevention map of Shanghai, confirming the validity and efficacy of the selected indicators and evaluation methodologies. The findings suggest that the overall risk level in the study area is relatively low, with high-risk zones concentrated in densely populated and economically urbanized central districts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

LS is a geological phenomenon1,2 in which terrestrial topography experiences subsidence induced vertical and horizontal changes, either gradually or through sudden collapse. This process can be caused by natural factors such as land compaction, seismic activity and peat carbonation, as well as anthropogenic factors such as over-exploitation of groundwater (GW)3, construction of underground infrastructure4, prolonged use of urban facilities5 and soil creep6. LS is present in many cities around the world7, such as Shanghai, Jakarta and Florence. With the acceleration of urbanization, the impact of human activities on LS is increasing, especially the over-extraction of groundwater and the construction of large-scale projects and other factors leading to the increasingly serious problem of LS8. LS is characterized by susceptibility, gradualness, latency, unevenness and irreversibility, and these characteristics make the subsidence problem difficult to repair, directly threatening infrastructure safety, socio-economic development and the safety of human lives and property.

LS is a complex phenomenon that is influenced by a number of factors. It is difficult to accurately determine the causes of LS and their interactions through qualitative analysis or simple correlation analysis alone. In order to effectively predict the disasters that may be caused by LS, it is necessary to develop a comprehensive risk assessment model9. Although in recent years scholars have conducted in-depth studies on the mechanisms of LS and analyzed its causes and simulations10,11,12, most of the studies focus on risk assessment of transient geohazards (landslides and mudslides), and relatively few studies have been conducted on the risk assessment of those slower-developing geohazards, such as LS.

Prediction of LS can be achieved through mathematical and numerical models. Mathematical models predict future trends mainly by analyzing historical subsidence data through statistical methods13,14, while numerical models make predictions by applying finite element or finite difference methods to simulate groundwater flow and surface deformation15,16,17. Nonetheless, the methods for assessing the damage that may result from LS are still not clear enough. The assessment of risks associated with LS can be performed using a variety of mathematical tools, including AHP18, bayesian networks19, fuzzy mathematical methods20, EWM21 and gray-theoretic methods22.

AHP is a widely applied multi-criteria decision-making method that systematically decomposes complex decision problems into hierarchical structures, enabling the integration of both qualitative and quantitative factors. This approach has been extensively employed in natural disaster risk assessment. For instance, in drought risk evaluation, AHP is used to assign weights to key factors such as annual precipitation, maximum temperature, and relative humidity23. Likewise, in urban flood risk assessment, AHP facilitates the classification of risk levels across different regions by analyzing variables such as digital elevation models and seasonal precipitation patterns24. However, the inherent subjectivity of AHP may introduce biases, potentially resulting in the overestimation or underestimation of disaster risks, thereby undermining the accuracy and reliability of assessment outcomes.

Relying solely on a single method may introduce excessive subjectivity or lead to an overreliance on mathematical models. To address this limitation, researchers have increasingly integrated AHP with complementary methodologies. For instance, AHP has been combined with the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to an Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) to enhance seismic risk assessment, facilitating more effective monitoring, analysis, and hazard mapping25. Additionally, fuzzy AHP has been applied in the assessment of multiple natural hazards26, incorporating fuzzy affiliation functions to refine evaluation scores. The core of the use of these methods in risk assessment is still the subjective calculation of weights, only reducing the impact of subjective judgments.

In contrast, EWM determines the weight of each indicator by computing its information entropy. Its key advantages include objectivity, the ability to process large-scale multidimensional data, and independence from expert judgment, thereby facilitating comprehensive assessments27. In recent years, a growing body of research has explored the integration of AHP and EWM, leading to significant advancements in disaster risk assessment. In the context of urban disaster assessment, the integration of AHP and EWM has proven to be highly effective. For instance, in collapse risk evaluation, AHP is employed to determine the weights of four standard layers, while EWM computes the weights of eleven indicator layers28. The final combined weights are derived through multiplicative integration, enabling a more precise and systematic analysis. Similarly, in flood risk assessment, AHP and EWM independently assign weights, which are subsequently synthesized using specific coefficients to perform superposition analysis and evaluation9. Moreover, in collapse risk analysis, game theory is applied to integrate the weights obtained from both methods, facilitating a more comprehensive assessment of dynamically evolving disaster-prone areas, particularly in extraction zones21. The AHP-EWM method effectively reduces the bias caused by subjective judgment. Based on this framework, we adopt matrix theory and coefficient of variation method to objectively integrate the derived weights to further reduce subjectivity. This integrated approach is not only theoretically advantageous, but also shows great potential in practical applications.

Therefore, this study adopts for the first time the theory of integrated risk assessment of natural hazards29 to assess the risk level of urban LS by combining the AHP, EWM, RS and geographic information system (GIS) techniques. Compared with the traditional assessment methods, this theory expands the assessment elements from three to four dimensions of hazard, exposure and vulnerability through multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA), the assessment of emergency response and recovery capacity is added. This approach provides a more comprehensive risk assessment from both subjective and objective perspectives, and effectively overcomes the bias that may be introduced by subjective judgments and the uncertainty in data collection in the AHP approach through coupled analysis. In addition, 15 evaluation indicators applicable to megacities are selected in this study, and the visualization and analysis of risk is achieved by using RS and GIS. By considering risks comprehensively from multiple levels, this method can help cities establish a more complete emergency management system and disaster warning mechanism, thus improving the overall resilience of the city and its ability to cope with emergencies, and providing decision makers with a comprehensive, scientific, standardized and convenient risk assessment tool.

Materials and methods

Research area

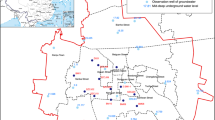

Shanghai (Fig. 1) is the largest city in China, strategically located on the eastern coast at geographic coordinates of 31°12′ N latitude and 121°30′ E longitude. The city lies at the southern end of the Yangtze River Delta, adjacent to the Yangtze River estuary, with the East China Sea to the east and Hangzhou Bay to the south. It is bordered by Jiangsu Province to the north and Zhejiang Province to the south. With its rich historical and cultural heritage, Shanghai also serves as one of China’s most vital centers for economic activity, finance, trade, and maritime shipping. However, LS poses a significant challenge for the city. This issue primarily arises from excessive groundwater extraction, land overloading, underground construction activities, and the natural compaction of sediments. In recent years, the rapid expansion and high-density urban development have exacerbated LS, complicating its monitoring and management.

The geographical location of the study area. ArcGIS 10.8 (https://www.esri.com) was used for visualization.

Methodology

This paper provides an exhaustive assessment of the risk of LS in Shanghai through four stages. Step A: Data pre-processing and collection, this paper relies on a large amount of non-spatial data and multi-source spatial data. Step B: Fifteen evaluation indicators were selected, which included hydrological and topographical conditions, population and facility distribution, and socio-economic situation. A comprehensive evaluation index system is developed and visualized, facilitating an intuitive representation of each indicator. Step C: Hierarchical analysis and entropy weighting are used to determine the subjective and objective weights of these indicators, and accordingly, comprehensive weighting is performed to calculate the combined weights of each indicator. Step D: Using the calculated weights, the Natural Hazard Index method is applied for overlay analysis, generating maps that assess regional disaster risks, vulnerability, and disaster mitigation capacity. Based on the results from raster layer weight calculations in ArcGIS, a LS risk map for Shanghai is generated, followed by a comprehensive regional LS risk map. A comparative analysis of risk level maps derived from various methods is also conducted. Figure 2 shows the technical steps in this study.

Risk assessment model and selection of indicators

Natural disasters result from the interaction of hazard factors, disaster-pregnant environments, and disaster bearing body. Disaster risk is primarily influenced by the dangerousness of hazard factors intensity, the instability of disaster-pregnant environments, and the exposure and vulnerability of the disaster bearing body. Furthermore, the capacity for disaster prevention and mitigation Capability plays a critical role in shaping regional disaster risk.

The Natural Disaster Risk Index (NDRI) functions as a risk assessment framework for disaster management, emergency response, and policy development. It is particularly effective in addressing urban disasters9 and agricultural meteorological hazards30, equipping regions with the tools to precisely identify potential risks, assess disaster risk, and develop targeted mitigation strategies.

This study is based on NDRI and divides the assessment of LS risk into four elements: Hazard (H), Exposure (E), Vulnerability (V), and Disaster Prevention and Mitigation Capability (C). Fifteen evaluation indicators were selected from the four components, with their classification based on expert recommendations and the natural breaks method. The selection criteria and corresponding scoring standards for these indicators are detailed in (Table 1). From this, a framework for assessing LS disasters is developed, expressed as9,28,31:

Where, H, E, V and C represent the values of hazard, exposure, vulnerability, and disaster prevention and mitigation capability. The term n denotes the total number of indicators. \(\:{\text{W}}_{\text{h}\text{i}},{\text{W}}_{\text{e}\text{i}},{\text{W}}_{\text{v}\text{i}},{\text{W}}_{\text{c}\text{i}}\) correspond to the weights of factors. \(\:{\text{X}}_{\text{h}\text{i}},{\text{X}}_{\text{e}\text{i}},{\text{X}}_{\text{v}\text{i}},{\text{X}}_{\text{c}\text{i}}\) are the normalized factors.

Data sources

The elevation data is derived from a geospatial data cloud with a spatial resolution of 30 meters. LS rate is obtained through SBAS-InSAR processing of 24-perspective Sentinel-1 data, with the dataset provided by the Alaska Satellite Facility (ASF). Groundwater extraction intensity is calculated using data from the Shanghai Geological Data Information Sharing Platform (SGDISP) and the Shanghai Municipal Water Authority (SMWB). Socio-economic variables, including population density, GDP per unit area, proportion of vulnerable populations, public budget capacity, education level, and institutional capacity, are extracted from the Shanghai Statistical Yearbook. River network density and building density are classified using an unsupervised approach in ENVI remote sensing software. Buffers are then created around the river network to measure distances to the rivers. The data for these variables is sourced from Landsat 8 OLI/TIRS in the geospatial data cloud. Road network density and subway density data are derived from Amap (Gaode Map). Land use type data were obtained by learning from existing studies processed in GEE32 (Table 1). In addition, taking into account existing research and professional advice, a natural breakpoint approach was used to categorize the risk indicators into five levels (Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5), including “very low,” “low,” “medium,” “high” and ”very high.”

Analysis of indicators and calculation of weights

Analysis of hazard indicators

In the risk assessment of LS in Shanghai, hazard analysis is the core of the assessment process, aiming to identify and quantify various risk factors that may lead to urban LS (Table 2). Three risk indicators are selected from the perspectives of disaster-causing factors and disaster-conceiving environment, and weights are assigned according to the influence of each indicator on the risk.

Hazard indicators: (a) Elevation, (b) Land subsidence rate, (c) GW extraction intensity. ArcGIS 10.8 (https://www.esri.com) was used for visualization.

Elevation (Fig. 3a): Given its geographical location, most regions of Shanghai exhibit lower elevations compared to other areas. Variations in elevation significantly influence the direction and velocity of surface water flow, which, in turn, impact groundwater levels, river discharge, and flood patterns35. The proximity of these low-lying regions to the coast further heightens their susceptibility to seawater intrusion and flooding. Consequently, a decrease in elevation correlates with an increased risk of LS.

Land subsidence rate (Fig. 3b): The average subsidence rate, spanning from January 2021 to December 2021, was derived from Sentinel-1 satellite data. The subsidence rate—defined as the velocity of LS—is a critical parameter in evaluating the impacts of LS and its associated risks36. This rate directly determines the severity of subsidence-related consequences and the urgency with which mitigation measures must be implemented. A higher subsidence rate exacerbates structural damage to buildings and industrial facilities, thereby complicating construction efforts and resource development. In regions where subsidence rates are elevated, the instability of geological strata necessitates greater investment in construction and amplifies the risks inherent in urban development and resource exploitation.

GW extraction intensity (Fig. 3c): The extent of groundwater extraction plays a pivotal role in influencing LS, particularly in regions undergoing rapid urbanization and experiencing significant agricultural demand. Groundwater is fundamental to maintaining the stability of subsurface structures, and its extraction directly undermines the support capacity of soil and rock layers, thereby inducing LS37. Shanghai, as the first city in China to identify regional LS, has primarily attributed this phenomenon to unsustainable groundwater extraction practices. The intensity of groundwater extraction is directly proportional to the likelihood and severity of LS. Conversely, implementing measures such as reducing groundwater extraction, optimizing extraction levels, and employing artificial recharge can effectively mitigate and prevent further subsidence.

Analysis of exposure indicators

Exposability refers to the position and status of an urban system, community or individual in the face of a specific risk, i.e. the degree of possible impact (Table 3). In this study, the exposure of Shanghai was assessed in detail by considering five indicators, including population density, GDP per unit area, river network density, building density and road density.

Exposure indicators: (a) Population density. (b) GDP per unit area. (c) River network density. (d) Building density. (e) Road network density. ArcGIS 10.8 (https://www.esri.com) was used for visualization.

Population density (Fig. 4a): The population of Shanghai is mainly concentrated in the main urban area, with fewer people in other areas. Population density is one of the very important exposure indicators in LS disasters18, directly related to the number of potentially affected people and areas. Areas with high population density usually have more buildings and infrastructures, gather a large number of people and properties, and increase the threat of disasters.

GDP per unit area (Fig. 4b): Shanghai’s GDP per unit area is higher in the central and eastern parts of the city and lower in other areas. GDP per unit area reflects regional economic conditions, and a high GDP per unit area often means that the region is characterized by intensive economic activity, dense infrastructure development, including large buildings, transportation networks, etc., and high losses, high exposure and high risk in the event of a disaster20.

Density of the river network (Fig. 4c): The higher density of the river network in Shanghai is concentrated in the western part of the main urban area, and areas with a dense river network are usually indicative of a strong exchange capacity between surface water and groundwater in that area. This dense river network helps groundwater recharge and flow, which theoretically can slow down the LS caused by over-abstraction of groundwater. However, if the river level drops, it may increase the dependence on groundwater, thus exacerbating LS38. Also, areas with high river network densities may experience more frequent flooding events. In summary, the denser the river network, the more exposed the area is and the more affected it is when LS occurs.

Building density (Fig. 4d): Building density reflects the degree of land development and is related to exposure to LS hazards. High building density areas have dense land cover, which increases the ground bearing capacity and the risk of LS disasters39. International studies have found that urbanized and high building density areas are vulnerable to disasters. Reducing building density can mitigate the threat of disasters and reduce exposure, thereby reducing risk.

Density of road network (Fig. 4e): The density of the road network reflects the level of transportation access and investment in fixed assets, which affects disaster exposure. Areas with high-density road networks are usually in urban and highly developed areas, with a high degree of utilization of underground space and viaducts. These areas have high construction investment, high exposure and higher risk of LS disasters.

Analysis of vulnerability indicators

Vulnerability reflects the inherent individual, social and environmental sensitivity and low coping capacity to LS events (Table 4). The vulnerability of different areas of Shanghai was explored in depth by selecting indicators such as the percentage of vulnerable population, land use type, distance from rivers, and density of subway lines.

Vulnerability indicators: (a) Proportion of vulnerable population. (b) Land use type. (c) Distance from river. (d) Subway density. ArcGIS 10.8 (https://www.esri.com) was used for visualization.

Proportion of vulnerable population (Fig. 5a): The proportion of vulnerable population is based on the proportion of the total population under 17 years of age and over 60 years of age40. The percentage of vulnerable people in the main urban areas is relatively large. Vulnerable people have lower incomes and lack sufficient financial support to take safety precautions and receive timely emergency assistance. Vulnerable people usually have fewer health and medical resources, and they are less capable of self-help and mutual assistance. The proportion of vulnerable people is selected as a vulnerability indicator to consider the distribution and vulnerability of special groups in LS disasters.

Land use type (Fig. 5b): In the risk assessment of LS, construction land and arable land are considered to have a higher vulnerability because these areas are more directly and severely affected by LS and buildings are more likely to be damaged. Cultivated land is extremely likely to experience LS due to the large amount of water it requires, but its risk level is usually considered lower than that of construction land in the assessment due to the smaller population8. The choice of land use type as a vulnerability indicator helps to assess the vulnerability of areas to LS events.

Distance from river (Fig. 5c): Land adjacent to rivers usually consists of fluvial sediments, which have been transported and deposited by water flows over the course of geological history. These sediments may be more easily compacted than soils in other areas, especially if the sediment layers are thick and have a high moisture content. As a result, areas near rivers are more susceptible to LS. The occurrence of LS is accompanied by vulnerability to flooding and greater damage41. In summary, the closer the river, the greater the vulnerability.

Subway density (Fig. 5d): Calculate the density of subway lines using the line density in GIS, and generate the density of subway lines in Shanghai with a search radius of 1 km. The denser the subway line area, the underground space is usually utilized to a higher degree, surrounded by many commercial and residential areas, with a huge flow of people, and the damage to the subway caused by subsidence is particularly prominent42,43. Therefore, the higher the subway density, the higher the vulnerability of the area.

Analysis of disaster prevention and mitigation capacity indicators

The analysis of disaster prevention and mitigation capacity focuses on assessing the ability of Shanghai to prevent, respond to and recover from LS disasters (Table 5). This capacity is not only the key to mitigating the impacts of LS, but also an important factor in enhancing urban resilience and ensuring public safety. This study provides an in-depth discussion of Shanghai’s disaster prevention and mitigation capacity through three main indicators: educational inputs, public budget and institutional capacity.

Disaster prevention and mitigation capacity indicators: (a) Public budget. (b) Educational level. (c) Institutional capability. ArcGIS 10.8 (https://www.esri.com) was used for visualization.

Public budgets (Fig. 6a): The strategic allocation of public funds is essential for reinforcing and enhancing critical infrastructure susceptible to LS, including transportation networks, bridges, and pipeline systems. These targeted investments are crucial in substantially mitigating the potential risks that LS poses to both public and private assets.

Educational inputs (Fig. 6b): The importance of education lies in its indirect contribution to mitigating the effects of LS. By raising the level of public education, it not only enhances people’s awareness of the problem of LS, but also promotes active community participation in preventive measures and early detection of subsidence. Education develops the specialized skills and professionals needed to deal with such problems, helping community members to act more effectively and work together to find sustainable solutions. Through education, people’s awareness of disasters can be raised, enabling them to make more informed choices when they occur, thus reducing losses44. Investment in education reflects the importance that a region places on education, and an increase in the level of education directly enhances the region’s ability to combat disasters.

Institutional capacity (Fig. 6c): When ground settlement occurs, strong institutional capacity can accelerate emergency response and disaster recovery. This includes timely rescue operations, rapid rehabilitation of infrastructure and support for affected communities. Institutional capacity is mainly reflected in the number of relevant personnel, which plays a crucial role in emergency response and post-disaster recovery; the more relevant personnel, the stronger the disaster prevention and mitigation capacity.

Weight calculation

Analytic hierarchy process (AHP)

AHP is a quantitative analysis method used for multi-criteria decision-making, created by the American operations researcher Thomas L. Saaty45. This method involves constructing a judgment matrix through pairwise comparisons of various decision criteria, then using eigenvalues and eigenvectors to analyze the weights of these comparisons. The steps of AHP are as follows31,46,47:

-

Step 1 Establish a hierarchical model, and Decompose the decision-making problem into a hierarchical structure composed of a standard layer and indicator layer. The criterion layer of this study is H-E-V-C, and the indicator layer is the selected fifteen indicators (Table 1).

-

Step 2 Expert scoring was used to compare and assess the interactions of the criteria and indicator layers two by two, respectively, resulting in a judgment matrix that quantifies the relative importance of each pair of indicators. The meaning of the scale is as follows (Table 6).

-

Step 3 Calculate the eigenvector of the maximum eigenvalue λ max of the judgment matrix.

$$\:{\varvec{\uplambda\:}}_{\mathbf{m}\mathbf{a}\mathbf{x}}=\sum\:_{\mathbf{i}=1}^{\mathbf{n}}\frac{{\left(\mathbf{A}\mathbf{W}\right)}_{\mathbf{i}}}{{\mathbf{n}\mathbf{W}}_{\mathbf{i}}}$$(6)Where, \(\:{\left(\text{A}\text{W}\right)}_{\text{i}}\) denotes the i-th component of vector \(\:\text{A}\text{W}\). \(\:\text{n}\) is the number of standard layer or indicator layer.

-

Step 4 The consistency of the judgment matrix is assessed through the application of the formula and table presented below, which outline the consistency index (CI) and random index (RI).

The Consistency Index (CI) is calculated as:

Where,\(\:{\lambda\:}_{max}\) is the maximum eigenvalue obtained from the judgment matrix. “\(\:n\)” is the number of criteria or alternatives.

The Consistency Ratio (CR) is then determined to assess the consistency of the pairwise comparisons:

Where,\(\:\text{R}\text{I}\) is the Random Index, which is a value derived from randomly generated matrices of order \(\:\text{n}\) and depends on the number of elements being compared (Table 7):

The decision rule for the \(\:CR\) is that if \(\:CR\) <0.10, the inconsistencies are acceptable; otherwise, the judgment matrix needs to be revised.

Through the above methods, The subjective weights of the standard and indicator layers were obtained. The results are shown (Table 8).

Entropy weight method (EWM)

Entropy weight method (EWM) is a multi-criteria evaluation method based on information entropy theory. Its core idea is to use the concept of information entropy to measure the uncertainty and dispersion of each indicator, and then derive the weight of each indicator. EWM can avoid the bias caused by subjective weighting, and objectively reflect the importance and contribution rate of indicators. The steps of EWM are as follows48,49:

-

Step 1 The data collected in this study are fifteen risk assessment indicators selected from the four latitudes H, E, V, C and ranked according to the sixteen districts of Shanghai. construct the Initial Evaluation Matrix: Create the original matrix:

$$\:X={\left[{x}_{ij}\right]}_{m\times\:n}$$(9)where \(\:m\) is objects and \(\:n\) is indicators.

-

Step 2 Data Standardization: Since the nature of indicators may differ, to eliminate the impact of different dimensions, the indicator values are normalized.

For positive indicators, the normalization formula is:

$$\:{x}_{ij}^{,}=\frac{{x}_{ij}-min\left({x}_{ij}\right)}{max\left({x}_{ij}\right)-min\left({x}_{ij}\right)}$$(10)For negative indicators, the normalization formula is:

$$\:{x}_{ij}^{,}=\frac{max\left({x}_{ij}\right)-{x}_{ij}}{max\left({x}_{ij}\right)-min\left({x}_{ij}\right)}$$(11)Where \(\:{x}_{ij}\) is the original value of the \(\:j\)th indicator for the \(\:i\)th unit, and \(\:{x}_{ij}^{,}\) is the normalized value.

-

Step 3 Calculate the Information Entropy \(\:{e}_{j}\) and Information Utility Value \(\:{d}_{j}\) :

$$\:{e}_{j}=-k\left[\sum\:_{i=1}^{n}{P}_{ij}ln\left({P}_{ij}\right)\right]$$(12)$$\:{\varvec{d}}_{\varvec{j}}=1-{\varvec{e}}_{\varvec{j}}$$(13)Where, \(\:{P}_{ij}={x}_{ij}/\sum\:_{i=1}^{n}{x}_{ij},K=1/{ln}(n)\)。\(\:{e}_{j}\) is the information entropy value of the \(\:j\)th indicator. The larger the entropy value \(\:{e}_{j}\) of an indicator, the smaller its role in the comprehensive evaluation, and consequently, the smaller its weight; and vice versa. \(\:{P}_{ij}\) is the proportion of the \(\:i\)-th unit for the \(\:j\)th indicator.

-

Step 4 Determine the Weight of Evaluation Indicators: After calculating the information entropy and utility values for each indicator, the weight of each indicator is determined by:

$$\:{\omega\:}_{j}=(1-{e}_{j})/\sum\:_{j=1}^{m}(1-{e}_{j})$$(14)where \(\:{{\upomega\:}}_{\text{j}}\)is the weight of the \(\:j\)th indicator.

The results are shown (Table 9).

Calculating composite weights

To overcome the limitations of using a single method for assigning weights, a combination of subjective and objective methods is employed to correct for biases50. By optimizing with a matrix approach based on AHP-EWM, the optimal composite weights can be obtained.

Let \(\:\alpha\:\) and \(\:\beta\:\) represent the relative importance of subjective and objective weights, respectively. We then use a matrix approach to determine the importance coefficients \(\:{\alpha\:}_{i}\) and \(\:{\beta\:}_{i}\) for the subjective and objective weights, where \(\:i=1,2,\dots\:,n\),with the formulas as follows:

where \(\:i=1,2,\cdots\:,n,{v}_{i}\) is the subjective weight obtained from the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), and \(\:{w}_{i}\) is the objective weight obtained from the Entropy Weight Method (EWM).

After obtaining the importance coefficients \(\:{\alpha\:}_{i}\) and \(\:{\beta\:}_{i}\) for the subjective and objective weights, we can calculate the composite weight \(\:{Q}_{i}\) for each indicator using the following formula:

By substituting the weights obtained from AHP and EWM into the above formulas, the final composite weights for the risk evaluation indicators of LS disaster in Shanghai can be determined, as shown in the table below (Table 10).

Results and discussion

Hazard, exposure, vulnerability and disaster prevention and mitigation capability rating map

In ArcGIS, indicators are reclassified by assigning values of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 to the respective categories of very low, low, medium, high, and very high. These reclassified indicators are then overlaid using the Raster Calculator based on the weighted combination of the indicators, as shown in Table 8. The resultant overlay map, processed through the natural breaks method, categorizes the risk levels into five distinct classes: very low, low, medium, high, and very high.

(a) Hazard, (b) Exposure, (c) Vulnerability, (d) Disaster prevention and mitigation capability. ArcGIS 10.8 (https://www.esri.com) was used for visualization.

As shown in the figure (Fig. 7a), the risk of LS in Shanghai is predominantly concentrated in coastal and riverine areas, likely due to lower elevations and elevated groundwater extraction rates in these regions. Conversely, the central urban area exhibits a lower risk, which may be attributed to targeted monitoring and preventive measures against LS in this zone.

The exposure analysis indicates (Fig. 7b) that the central urban areas of Shanghai have high exposure levels. These areas serve as commercial and educational hubs, characterized by a dense concentration of high-rise buildings and a complex road network. The intense concentration of economic and social activities in these regions correlates with high population density. This analysis helps prioritize areas in Shanghai that require focused attention when addressing urban hazards such as LS. Moreover, it provides essential decision-making support for future urban development planning, guiding efforts to promote sustainable economic growth while ensuring urban safety.

Vulnerable areas (Fig. 7c) are similarly concentrated in the central urban region. However, unlike the exposure levels, the areas of higher vulnerability are primarily located around subway systems and their adjacent areas, where there are numerous residential and commercial zones, high pedestrian traffic, and a significant concentration of vulnerable populations. Vulnerability analysis is instrumental in identifying the populations and regions within the city that require the most protection. By mitigating the vulnerability of these areas and populations, the overall resilience of the city to natural disasters such as LS can be significantly enhanced.

Disaster prevention and mitigation capacity (Fig. 7d) is stronger in areas with higher awareness and more robust detection and preventive measures against LS. This analysis underscores the importance of strengthening disaster prevention and mitigation capacities to alleviate the impacts of LS. Achieving this goal requires not only government financial investment and educational initiatives but also the establishment of an efficient institutional framework that encourages broad participation from all sectors of society.

Regional LS risk level map

Regional LS risk map. ArcGIS 10.8 (https://www.esri.com) was used for visualization.

Using the Raster Calculator in ArcGIS, regional LS levels were calculated according to the aforementioned (formula1), and subsequently classified into five categories using the natural breaks method, as depicted in (Fig. 8). High-risk areas are primarily located in the central urban area and Pudong New Area, where economic prosperity and population density are relatively high. In contrast, low-risk areas are found mainly on Chongming Island and in the southern regions, where the land is expansive, the population is sparse, and infrastructure and buildings are less prevalent.

Validation and discussion

The current LS management regulations are based on a series of surveys conducted by the Shanghai Geological Survey Bureau, which delineate the LS control zones currently adopted by the Shanghai municipal government. A comparison of the results from Figs. 8 and 9 indicates that the very high-risk and high-risk areas identified in Fig. 8 correspond to the major prevention zones in Fig. 9, the medium-risk areas in (Fig. 8) align with the medium prevention zones in Fig. 9, and the very low-risk and low-risk areas in Fig. 8 match the general prevention zones in Fig. 9.

Present prevention zone for Land subsidence in Shanghai. ArcGIS 10.8 (https://www.esri.com) was used for visualization.

Historical cumulative of land subsidence in Shanghai. ArcGIS 10.8 (https://www.esri.com) was used for visualization.

The historical cumulative subsidence data for Shanghai (Fig. 10) reveals a strong correlation between areas with significant subsidence and those designated as high-risk zones. The areas of these various risk zones were calculated and compared (Fig. 11). AHP yielded results of 58.48%, 15.97%, 15.26%, 6.42%, and 3.86%, while the Entropy Weight Method (EWM) produced results of 75.01%, 15.03%, 6.59%, 1.99%, and 1.39%. The combined AHP-EWM method generated results of 67.00%, 17.87%, 9.25%, 3.39%, and 2.48%. The distribution of risk levels based on Shanghai’s historical cumulative subsidence was 68.56%, 16.96%, 8.49%, 3.47%, and 2.50%. The comparison reveals that AHP generally identifies higher risks, possibly due to the subjective belief among experts that Shanghai’s geological and anthropogenic conditions may exacerbate LS. In contrast, EWM tends to show lower risks, likely reflecting the impact of significant recent efforts to control and prevent LS, which have objectively reduced the likelihood and severity of subsidence. The AHP-EWM results closely align with historical subsidence data, indicating that this method provides a more accurate and scientifically robust risk analysis for urban LS prevention. Moreover, the consistency of risk analysis trends across AHP, EWM, and AHP-EWM with historical subsidence data suggests that the indicators selected in this study, along with the application of advanced technologies such as RS, GEE, and SBAS-InSAR, are both scientifically valid and effective.

Current urban LS risk assessments are subject to several significant limitations. First, challenges related to data quality and availability—particularly the lack of high-precision, long-term monitoring data—restrict the accuracy of these assessments. Second, existing models often oversimplify the complex interplay of geological and environmental factors, making it difficult to fully capture the dynamic nature of urban environments and subsurface conditions20. Additionally, the multiscale nature of subsidence complicates the simultaneous and precise quantification of both macro- and micro-level impacts. Furthermore, these models frequently overlook the influence of socioeconomic factors, ecological changes, and human activities, leading to incomplete and potentially misleading assessment outcomes18. Finally, there is a notable disconnect between risk assessments, emergency response strategies, and risk management processes, exacerbated by the absence of effective decision-support tools. This gap hampers the translation of assessment findings into actionable policies and mitigation strategies51. In conclusion, current risk assessment methods suffer from limitations in geographic applicability, model precision, and the integration of socioeconomic context. Addressing these challenges requires the integration of multi-source data, the optimization of assessment models, and the promotion of interdisciplinary collaboration. This study addresses these gaps by thoroughly examining the complexity of LS. It employs emerging technologies for data collection and applies multi-dimensional data fusion, spatial analysis, and region-specific assessments to construct a more precise and scientifically rigorous risk prediction framework.

Conclusion

This study employs the AHP-EWM method to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of LS disaster risks in megacities, using Shanghai as a case study. The application of AHP-EWM, RS, SBAS-InSAR and GEE in LS risk assessment is detailed. The evaluation results were validated against Shanghai’s existing LS control zones and historical subsidence data. The key research findings are summarized as follows.

Unlike traditional risk assessment methods, this study introduces a novel composite framework that integrates multi-source data with multi-level analysis. This approach effectively captures the complexity of LS from various perspectives, enhancing both the rigor and scientific credibility of the assessment outcomes.

The study employs a hybrid AHP-EWM methodology, combined with matrix theory, and introduces a dynamic importance index (\(\:{\upalpha\:}\) and \(\:{\upbeta\:}\)) for optimization. This index facilitates real-time adjustments based on varying data conditions, maximizing the value of expert judgment when data is sparse or uncertain, while relying on objective analysis when data is abundant. By mitigating human bias, the proposed method significantly enhances the adaptability of the risk assessment system, enabling it to address complex, multi-dimensional risk evaluations.

In evaluating LS risk in Shanghai, the integration of AHP-EWM with multi-source data reveals that high-risk areas are concentrated in the city’s central districts, where urbanization has advanced most rapidly. The results from the AHP-EWM method not only outperform those from AHP and EWM individually but also closely align with Shanghai’s historical cumulative subsidence data. This demonstrates the method’s suitability for LS risk assessments in large cities, providing reliable results. Furthermore, it allows for the identification of distinct risk zones, which can inform the development of targeted risk mitigation strategies.

Although this study utilized RS and InSAR technologies to simplify the complexities of traditional LS detection and assessment, certain data, such as groundwater extraction intensity, were still sourced from large-scale manual surveys conducted by the government. Future research could leverage GRACE (Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment) satellite data, in conjunction with the Global Land Data Assimilation System (GLDAS), to calculate changes in groundwater storage, further improving the accuracy and efficiency of LS detection and assessment.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The software used in this study, with the following versions and URL: ArcGIS 10.8 (https://www.esri.com), ENVI 5.6 (https://envi.geoscene.cn/) and SARscape 5.6.2 (https://envi.geoscene.cn/).

References

Gambolati, G. & Teatini, P. Geomechanics of subsurface water withdrawal and injection. Water Resour. Res. 51, 3922–3955. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014WR016841 (2015).

Zoccarato, C., Minderhoud, P. S. J. & Teatini, P. The role of sedimentation and natural compaction in a prograding delta: insights from the mega Mekong delta, Vietnam. Sci. Rep. 8, 11437. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29734-7 (2018).

Wang, H. M., Wang, Y., Jiao, X. & Qian, G. R. Risk management of land subsidence in Shanghai. Desalin. Water Treat. 52, 1122–1129. https://doi.org/10.1080/19443994.2013.826337 (2014).

Wu, Y. X., Shen, J. S., Cheng, W. C. & Hino, T. Semi-analytical solution to pumping test data with barrier, wellbore storage, and partial penetration effects. Eng. Geol. 226, 44–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2017.05.011 (2017).

Shen, S. L., Wu, H. N., Cui, Y. J. & Yin, Z. Y. Long-term settlement behaviour of metro tunnels in the soft deposits of Shanghai. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 40, 309–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2013.10.013 (2014).

Zhu, Q. Y., Yin, Z. Y., Hicher, P. Y. & Shen, S. L. Nonlinearity of one-dimensional creep characteristics of soft clays. Acta Geotech. 11, 887–900. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-015-0411-y (2016).

Herrera-García, G. et al. Mapping the global threat of land subsidence. Science 371, 34–36. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb8549 (2021).

Rahmati, O. et al. Land subsidence hazard modeling: machine learning to identify predictors and the role of human activities. J. Environ. Manag. 236, 466–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.02.020 (2019).

Liu, G. et al. Geographic-information-system-based risk assessment of flooding in Changchun urban rail transit system. Remote Sens. 15, 1 (2023).

Davydzenka, T., Tahmasebi, P. & Shokri, N. Unveiling the global extent of land subsidence: the sinking crisis. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL104497. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GL104497 (2024).

Islam, M. S. & Iskander, M. Twin tunnelling induced ground settlements: A review. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 110, 103614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2020.103614 (2021).

Thomas, A. V. et al. Landslide susceptibility zonation of Idukki district using GIS in the aftermath of 2018 Kerala floods and landslides: a comparison of AHP and frequency ratio methods. J. Geovis. Spat. Anal. 5, 21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41651-021-00090-x (2021).

Ma, L., Xu, Y. S., Shen, S. L. & Sun, W. J. Evaluation of the hydraulic conductivity of aquifers with piles. Hydrogeol. J. 22, 371–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-013-1068-y (2014).

Xu, Y. S., Ma, L., Shen, S. L. & Sun, W. J. Evaluation of land subsidence by considering underground structures that penetrate the aquifers of Shanghai, China. Hydrogeol. J. 20, 1623–1634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-012-0892-9 (2012).

Shen, S. L., Ma, L., Xu, Y. S. & Yin, Z. Y. Interpretation of increased deformation rate in aquifer IV due to groundwater pumping in Shanghai. Can. Geotech. J. 50, 1129–1142. https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj-2013-0042 (2013).

Shen, S. L. & Xu, Y. S. Numerical evaluation of land subsidence induced by groundwater pumping in Shanghai. Can. Geotech. J. 48, 1378–1392. https://doi.org/10.1139/t11-049 (2011).

Wu, H. N., Shen, S. L. & Yang, J. Identification of tunnel settlement caused by land subsidence in soft deposit of Shanghai. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 31, 04017092. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CF.1943-5509.0001082 (2017).

Zhang, Z. et al. Hazard assessment model of ground subsidence coupling AHP, RS and GIS—A case study of Shanghai. Gondwana Res. 117, 344–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2023.01.014 (2023).

Jin, Y. F., Yin, Z. Y., Shen, S. L. & Hicher, P. Y. Selection of sand models and identification of parameters using an enhanced genetic algorithm. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 40, 1219–1240. https://doi.org/10.1002/nag.2487 (2016).

Lyu, H. M., Shen, S. L., Zhou, A. & Yang, J. Risk assessment of mega-city infrastructures related to land subsidence using improved trapezoidal FAHP. Sci. Total Environ. 717, 135310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135310 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Study on stability evaluation of Goaf based on AHP and EWM—taking the Northern new district of Liaoyuan City as an example. Sci. Rep. 14, 17876. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68858-x (2024).

Ishikawa, A. et al. The max-min Delphi method and fuzzy Delphi method via fuzzy integration. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 55, 241–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-0114(93)90251-C (1993).

Zarei, A. R., Moghimi, M. M. & Koohi, E. Sensitivity assessment to the occurrence of different types of droughts using GIS and AHP techniques. Water Resour. Manag. 35, 3593–3615. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-021-02906-3 (2021).

Tempa, K. District flood vulnerability assessment using analytic hierarchy process (AHP) with historical flood events in Bhutan. PLoS ONE 17, e0270467. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270467 (2022).

Jena, R., Pradhan, B. & Integrated ANN-cross-validation and AHP-TOPSIS model to improve earthquake risk assessment. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 50, 101723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101723 (2020).

Pirasteh, S. et al. Enhancing vulnerability assessment through spatially explicit modeling of mountain social-ecological systems exposed to multiple environmental hazards. Sci. Total Environ. 930, 172744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.172744 (2024).

Bao, Q., Yuxin, Z., Yuxiao, W. & Feng, Y. Can entropy weight method correctly reflect the distinction of water quality indices? Water Resour. Manag. 34, 3667–3674. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-020-02641-1 (2020).

Lu, Z. et al. Application of AHP-ICM and AHP-EWM in collapse disaster risk mapping in Huinan County. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 12, 1 (2023).

Zhang, J. Q., Liang, J. D., Liu, X. P. & Tong, Z. J. GIS-based risk assessment of ecological disasters in Jilin Province, Northeast China. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 15, 727–745. https://doi.org/10.1080/10807030903050962 (2009).

Ma, Y. et al. Assessment of maize drought risk in Midwestern Jilin Province: A comparative analysis of TOPSIS and VIKOR models. Remote Sens. 14, 1 (2022).

Zhang, Z., Zhang, J., Zhang, Y., Chen, Y. & Yan, J. Urban flood resilience evaluation based on GIS and multi-source data: A case study of Changchun City. Remote Sens. 15, 1 (2023).

Yang, J. & Huang, X. The 30 m annual land cover dataset and its dynamics in China from 1990 to 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 3907–3925 (2021).

Gong, S. L., Li, C. & Yang, S. L. The microscopic characteristics of Shanghai soft clay and its effect on soil body deformation and land subsidence. Environ. Geol. 56, 1051–1056. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00254-008-1205-4 (2009).

Chai, L., Xie, X., Wang, C., Tang, G. & Song, Z. Ground subsidence risk assessment method using PS-InSAR and LightGBM: a case study of Shanghai metro network. Int. J. Digit. Earth 17, 2297842. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538947.2023.2297842 (2024).

Nicholls, R. J. et al. A global analysis of subsidence, relative sea-level change and coastal flood exposure. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 338–342. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-00993-z (2021).

Yang, X., Jia, C., Sun, H., Yang, T. & Yao, Y. Integrating multi-source data to assess land subsidence sensitivity and management policies. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 104, 107315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2023.107315 (2024).

Haley, M., Ahmed, M., Gebremichael, E., Murgulet, D. & Starek, M. Land subsidence in the Texas coastal Bend: locations, rates, triggers, and consequences. Remote Sens. 14 (2022).

Sharifi, A., Khodaei, B., Ahrari, A. & Hashemi, H. Torabi Haghighi, A. Can river flow prevent land subsidence in urban areas? Sci. Total Environ. 917, 170557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.170557 (2024).

Cao, Q., Zhang, Y., Yang, L., Chen, J. & Hou, C. Unveiling the driving factors of urban land subsidence in Beijing, China. Sci. Total Environ. 916, 170134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.170134 (2024).

Huang, F. et al. Urban flooding disaster risk assessment utilizing the maxent model and game theory: A case study of Changchun. China Sustain. 16, 1 (2024).

Jiang, H., Zhang, J., Liu, Y., Li, J. & Fang, Z. N. Does flooding get worse with subsiding land? Investigating the impacts of land subsidence on flood inundation from hurricane Harvey. Sci. Total Environ. 865, 161072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.161072 (2023).

Lyu, H. M., Shen, S. L., Zhou, A. N. & Zhou, W. H. Flood risk assessment of metro systems in a subsiding environment using the interval FAHP-FCA approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 50, 101682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101682 (2019).

Xiao, J. et al. Long-term settlement of metro viaduct Piers: A case study in Shanghai soft soil. Transport. Geotech. 42, 101075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trgeo.2023.101075 (2023).

Singkran, N. & Kandasamy, J. Developing a strategic flood risk management framework for Bangkok, Thailand. Nat. Hazards 84, 933–957. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-016-2467-x (2016).

Saaty, T. L. Decision making—the analytic hierarchy and network processes (AHP/ANP). J. Syst. Sci. Syst. Eng. 13, 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11518-006-0151-5 (2004).

Dong, Q. & Cooper, O. An orders-of-magnitude AHP supply chain risk assessment framework. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 182, 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2016.08.021 (2016). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/

Stefanidis, S. & Stathis, D. Assessment of flood hazard based on natural and anthropogenic factors using analytic hierarchy process (AHP). Nat. Hazards 68, 569–585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-013-0639-5 (2013).

Xu, H., Ma, C., Lian, J., Xu, K. & Chaima, E. Urban flooding risk assessment based on an integrated k-means cluster algorithm and improved entropy weight method in the region of Haikou, China. J. Hydrol. 563, 975–986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2018.06.060 (2018).

Wang, N. & Zhang, Y. Research on evaluation of Wuhan air pollution emission level based on entropy weight method. Sci. Rep. 14, 5012. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55554-z (2024).

Na, W. & Zhao, Z. C. The comprehensive evaluation method of low-carbon campus based on analytic hierarchy process and weights of entropy. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 23, 9308–9319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-01025-0 (2021).

Fangtian, L., Erqi, X. & Hongqi, Z. An improved typhoon risk model coupled with mitigation capacity and its relationship to disaster losses. J. Clean. Prod. 357, 1 (2022).

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Scientific and Technology Research and DevelopmentProgram of Jilin Province (212556SF010483432).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z.; Methodology, Y.Z. and G.L.; Formal analysis, Y.Z.and J.Z.; Data curation, Y.Z. and H.C.; Writing—original draft, Y.Z.; Writing—review & editing, Y.Z. and J.X.; Funding acquisition, Y.Z. and Z.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhan, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhang, J. et al. Risk assessment of land subsidence in Shanghai municipality based on AHP and EWM. Sci Rep 15, 7339 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91109-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91109-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Integrating Explainable Machine Learning and LSTM with Multiple Factors for Mechanism Identification and Prediction of Land Deformation in the North Henan Plain

Journal of Geovisualization and Spatial Analysis (2026)

-

Developing an element system of hospital resilience to medical run in major emerging infectious diseases: a Delphi study

BMC Infectious Diseases (2025)

-

A methodological design and an empirical study for assessing the maturity of an UASR based on the AHP-EWM and the FSEM fusion model

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Enhancing urban quality of life evaluation using spatial multi criteria analysis

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Development and application of advanced learning models for predicting the land subsidence due to coal mining

Scientific Reports (2025)