Abstract

Stroke is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with modifiable risk factors being crucial for prevention efforts. Magnesium, an essential mineral involved in numerous physiological processes, is linked to cardiovascular health. However, the relationship between magnesium status, assessed through the Magnesium Depletion Score (MDS), and stroke risk remains underexplored. This study aims to investigate the association between MDS and stroke incidence, as well as the potential correlation between MDS and all-cause and cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality among US adults. Furthermore, we explore the mediation role of Life’s Essential 8 (LE8) in the relationship between MDS and stroke. Utilizing data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 1999 to 2018, we conducted a cross-sectional analysis of 44,588 participants. Participants were divided into three groups based on their MDS levels: none to low (MDS = 0–1), middle (MDS = 2), and high (MDS = 3–5). Multivariable logistic regression models were employed to assess the relationship between MDS and stroke risk, adjusting for multiple confounders. Additionally, Cox regression models and Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to evaluate the association between MDS and mortality outcomes. Subgroup and mediation analyses were performed to explore the role of LE8 in MDS associations with the risk of stroke. Higher MDS was significantly associated with increased stroke risk in a dose-dependent manner. Participants with high MDS scores (3–5) had an odds ratio (OR) of 1.96 (95% CI 1.55–2.49) for stroke compared to those with low MDS scores (0–1). For all-cause mortality, high MDS was associated with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.73 (95% CI 1.41–2.09), and for CVD mortality, the HR was 2.01 (95% CI 1.49–2.71). Kaplan-Meier analyses revealed lower survival probabilities with increasing MDS levels. Subgroup analyses revealed that higher MDS was associated with increased stroke risk across age and gender groups, with stronger effects observed in older individuals, males, and those with higher cardiovascular risk factors, while LE8 mediated 26.5% of this relationship. Our findings provide strong evidence that higher MDS is significantly associated with increased stroke risk and higher all-cause and CVD mortality among stroke patients. LE8 plays a significant mediating role in this association.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stroke is a leading global cause of morbidity and mortality, resulting from an interruption in blood supply to the brain1. It can manifest as ischemic or hemorrhagic, with severe consequences such as disability or death2. Identifying modifiable risk factors is crucial for stroke prevention.

Magnesium is an essential mineral involved in numerous physiological processes. It serves as a cofactor for over 350 enzymatic reactions, including those critical for muscle and nerve function, protein synthesis, blood glucose control, and blood pressure regulation. Magnesium is also crucial for DNA synthesis and the stabilization of mitochondrial membranes, highlighting its fundamental role in cellular and metabolic functions3,4. Despite its importance, magnesium deficiency affects an estimated 48% of the US population, with significant implications for cardiovascular health5. Magnesium regulates vascular tone and endothelial function, reducing blood pressure and the risk of hypertension through its natural calcium antagonist properties6. Hypomagnesemia is associated with elevated inflammation markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), and endothelial dysfunction, both of which are risk factors for cardiovascular diseases (CVD), including stroke and coronary heart disease7,8. While serum magnesium levels are commonly measured, they often fail to reflect the body’s true magnesium status due to the kidneys’ regulatory functions9,10. The magnesium tolerance test (MTT) is recognized as the most accurate method but is complex and clinically impractical11. To address these limitations, Fan et al.12 developed the Magnesium Depletion Score (MDS), which considers kidney reabsorption capability and has been shown to be more sensitive in detecting magnesium deficiency than traditional measurements. The MDS was validated against MTT, demonstrating a higher area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve than serum or urine magnesium levels. However, the specific relationship between MDS and stroke risk remains underexplored.

In 2010, the American Heart Association (AHA) introduced Life’s Simple 7 (LS7) as key indicators for cardiovascular health (CVH)13. Recently, LS7 was updated to include sleep health, resulting in Life’s Essential 8 (LE8), which comprises four health behaviors—diet, physical activity, nicotine exposure, and sleep health—and four health factors—BMI, blood lipids, blood glucose, and blood pressure14. Because the relationship between MDS and stroke is also influenced by lifestyle15, LE8 serves as a robust tool to explore this connection. While LE8 has been associated with reduced risks of CVD, all-cause mortality, and chronic diseases16, its specific link with magnesium depletion is unclear but potentially critical for stroke prevention.

In this research, we utilize data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) collected from 1999 to 2018 to investigate the association between magnesium depletion and stroke incidence. Furthermore, we investigate whether the MDS is longitudinally correlated with elevated risks of all-cause and CVD mortality among participants with a history of stroke. Additionally, we examine the mediating role of LE8 to evaluate how magnesium status, lifestyle, and clinical factors collectively influence stroke outcomes, providing a comprehensive understanding of these interconnections.

Methods

Study population and ethics

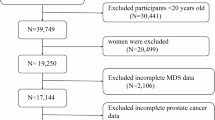

We used data from the NHANES (1999–2018). NHANES is an ongoing program by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to assess the health and nutritional status of non-institutionalized US civilians. The survey employs a complex, stratified, multistage probability sampling design to recruit a nationally representative sample of approximately 5,000 participants annually17,18,19. Data collection included in-home interviews and mobile examination centers, covering demographics, dietary intake, physical examinations, laboratory tests, and questionnaire data. The NHANES survey received approval from the National Center for Health Statistics Ethics Review Board, and all participants provided informed consent. All NHANES data are publicly available on the CDC website (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes)20. Initially, 101,316 participants from ten consecutive NHANES cycles (1999–2018) were included. The exclusion criteria were: (1) participants aged < 18 years (n = 42,112); and (2) participants with missing data on MDS and stroke (n = 14,646). After applying these criteria, 44,588 eligible subjects were included in the final analysis. The sample selection process details are presented in Fig. 1.

Assessment of MDS and magnesium intake

The MDS was calculated to evaluate overall body magnesium status, as described elsewhere12. The MDS incorporates four factors: diuretic use (one point for current use), proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use (one point for current use), renal function (one point for 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 ≤ estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] < 90 mL/min/1.73 m2; two points for eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), and alcohol consumption (one point for heavy drinking). In this study, MDS values were categorized into three groups: “none to low” (MDS = 0–1), “middle” (MDS = 2), and “high” (MDS = 3–5) to facilitate interpretation and application. The quantity and types of food and beverages consumed were assessed using NHANES data from two 24-hour recall interviews. The first 24-hour personal interview was conducted in the Mobile Examination Center (MEC), and the second was conducted by telephone approximately 3–10 days later, according to the survey procedure. Total dietary magnesium intake was estimated by averaging the data from these two 24-hour dietary recalls.

Assessment of stroke

Stroke was defined by a self-reported previous diagnosis from a physician during face-to-face interviews. Participants who answered “yes” to the question, “Have you ever been told by a physician or health professional that you had a stroke?” were classified as having had a stroke. It should be noted that self-reported measures are susceptible to recall bias, which may affect data interpretation. Additionally, despite the absence of specific information on stroke type in the NHANES database, it is likely that the majority of stroke participants in this study experienced ischemic strokes. This assumption is based on the higher prevalence of ischemic stroke among stroke patients and its closer association with chronic low-grade inflammatory status21,22.

Measurement of LE8

The LE8 score consists of four health behaviors—diet, physical activity, nicotine exposure, and sleep duration—and four health factors, including body mass index (BMI), non-high-density lipoprotein (non-HDL) cholesterol, blood glucose, and blood pressure. Dietary patterns were evaluated using the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) 2015, based on a 24-hour dietary recall from the participants23. Information on physical activity, nicotine use, sleep habits, diabetes history, and medication use was collected through self-reported surveys. Height, weight, and blood pressure measurements were obtained during physical examinations. BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m²). Blood samples were analyzed to measure non-HDL cholesterol, plasma glucose, and hemoglobin A1c. The method for calculating the LE8 score within the NHANES dataset has been previously described. Each of the eight cardiovascular health (CVH) indicators was given a score between 0 and 100, and the overall LE8 score was determined by averaging these individual scores. High CVH was defined by a LE8 score of 80–100, moderate CVH by a score of 50–79, and low CVH by a score ranging from 0 to 4914. These same thresholds were applied in our study to categorize the subscales.

Covariates

NHANES collects sociodemographic information through structured interviews. Demographic characteristics, including age, sex, race, education level, and poverty income ratio (PIR), were self-reported by interviewees. The questionnaire data included information on smoking and drinking status. Smoking status was categorized as: never smokers (smoked less than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime), former smokers (smoked more than 100 cigarettes but do not smoke currently), and current smokers (smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and smoke some days or every day)24. Drinking status was classified as: never drinker (had < 12 drinks in their lifetime), former drinker (had ≥ 12 drinks in one year but did not drink in the last year), mild drinker (≤ 2 drinks/day for men and ≤ 1 drink/day for women), moderate drinker (≤ 4 drinks/day for men and ≤ 3 drinks/day for women, but not a mild drinker), and heavier drinker (≥ 5 drinks/day for men and ≥ 4 drinks/day for women)25. Diabetes diagnosis was based on any of the following criteria: a doctor’s diagnosis, glycated hemoglobin > 6.5%, fasting glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, random blood glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, 2-hour OGTT blood glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, or use of diabetes medication or insulin. Hypertension was defined as a mean systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg, or current use of antihypertensive medication. Other chronic comorbidities, such as hyperlipidemia, were identified through a doctor’s diagnosis or self-report. Measurements of waist size, weight, and height were taken by well-trained health technologists according to the anthropometry procedure manual. Additionally, laboratory parameters such as glucose, insulin, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine (Cre), uric acid, triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), calcium (Ca), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) were assessed.

Mortality

The National Center for Health Statistics created a public-use linked mortality file for NHANES 1999 to 2018, based on data from the National Death Index (NDI)26. The primary outcomes were all-cause mortality and CVD mortality, with CVD mortality identified using ICD-10 codes I00 to I09, I11, I13, I20 to I51, and I60 to I69. The follow-up period was calculated from the NHANES interview date to the date of death or December 31, 2019.

Statistical analysis

According to CDC guidelines, sample weights from the complex multistage cluster survey design were applied in our study. Continuous variables were presented as weighted means and standard deviations (SD), while categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. To detect differences in baseline characteristics between stroke and non-stroke participants, continuous variables were compared using the Student’s t-test, and categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test. Multivariable logistic regression was used to investigate the relationship between MDS risk and stroke, adjusting for confounding factors such as age, sex, race, education, PIR, smoking, drinking, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, BMI, waist circumference, creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, serum uric acid, calcium intake, magnesium intake, LE8 score, and eGFR. To examine the association between MDS and mortality from all causes and CVD-related factors, we constructed three Cox regression models with the aforementioned multivariable adjustments. Kaplan–Meier curves were used to present the rates of all-cause and CVD-related mortality. To investigate dose-response associations between MDS and mortality, restricted cubic spline (RCS) regression was performed. The number of nodes was determined based on the lowest value of the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). The LE8 score was classified into categories based on the previously defined scoring intervals. Subgroup analyses were performed using stratified multivariate regression models, with stratification based on age, sex, and LE8 categories. For the mediation analysis, a mediating variable (M) was hypothesized to influence the relationship between the independent variable (X) and the dependent variable (Y)27. Both the indirect and direct effects of the MDS on stroke were analyzed separately. In this framework, the MDS served as the independent variable (X), stroke was the dependent variable (Y), and the LE8 score was the mediated variables (M). A p-value below 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using R software (R-project ®; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, ver. 4.2.1).

Results

Baseline characteristics of study participants

A total of 1,751 individuals with stroke were included in the analysis, with a mean age of 64.24 years. Compared to non-stroke individuals, stroke patients were more likely to be older, female, non-Hispanic White, less educated, and of lower income. They were more frequently smokers and less likely to consume alcohol. Additionally, stroke patients had higher incidences of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes. Stroke patients also exhibited higher levels of BMI, blood glucose, and lipid indices, a reduced eGFR, and significantly lower calcium and magnesium intake (all P < 0.05). The stroke group exhibited a significantly higher MDS score compared to the non-stroke group [1.60 (1.53, 1.66) vs. 0.79 (0.77, 0.81), p < 0.001]. Detailed information on the baseline characteristics of all participants, grouped by stroke status, is presented in Tables 1 and 2. Additionally, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 provide baseline characteristics of the study participants and various physical and laboratory indices categorized by MDS scores. As MDS increased, participants were older, had higher levels of BMI and WC, were less educated, had lower incomes, and were more likely to be former drinkers and former smokers (all P < 0.001). Laboratory tests also showed that creatinine, uric acid, and BUN levels were relatively higher in the high MDS group (all P < 0.001). Compared to participants in the none-to-low MDS group, those in the middle and high MDS groups had a higher prevalence of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and stroke (all P < 0.001). Conversely, the proportion of males, eGFR levels, and dietary intake of calcium and magnesium were lower in these groups. In Supplementary Table 3, LE8 scores were significantly higher in non-stroke individuals (68.78, 95% CI: 68.32–69.23) compared to stroke individuals (57.71, 95% CI: 56.45–58.97, P < 0.001). Among the MDS categories, LE8 scores decreased as the MDS score increased (P < 0.001). Regarding health behaviors, no significant difference was found in diet scores between stroke and non-stroke groups (P = 0.091). However, physical activity and sleep health scores were significantly lower in stroke individuals (P < 0.001). These health behavior scores were decreased with higher MDS categories. Health factors, such as BMI, blood lipids, blood glucose, and blood pressure, were all lower in stroke individuals compared to non-stroke individuals (P < 0.001). Similar to health behaviors, these health factors also showed a decline as MDS scores increased (P < 0.001).

Association between MDS and stroke

To explore the relationship between MDS and stroke, a weighted multiple regression analysis with covariate adjustments was conducted (Table 3). As a continuous variable, MDS was associated with stroke in all models (crude: OR = 2.10, 95% CI: 2.00–2.21, P < 0.001; Model 1: OR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.30–1.50, P < 0.001; Model 2: OR = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.22–1.41, P < 0.001). When MDS was divided into three groups, a higher stroke risk was observed in the middle and high groups compared to the none-to-low group in Model 2 (middle: OR = 1.44, 95% CI: 1.19–1.74, P < 0.001; high: OR = 1.96, 95% CI: 1.55–2.49, P < 0.001), with a positive trend (P for trend < 0.001).

Associations between MDS and mortality

A total of 44,511 subjects with stroke had follow-up data available. During a median follow-up period of 81 months, 6,947 all-cause deaths and 2,178 CVD deaths were identified. Kaplan-Meier curves revealed survival differences based on MDS results. For all-cause mortality, the lowest survival probability was among participants with MDS 3–5, intermediate for MDS = 2, and highest for MDS 0–1 (log-rank P < 0.001, Fig. 2A). A similar pattern was observed for CVD deaths (log-rank P < 0.001, Fig. 2B). Figure 3 shows statistically significant nonlinear associations between MDS and both all-cause and CVD mortality after adjusting for confounders (P < 0.001), suggesting Cox regression models for further evaluation. Table 4 demonstrates that, after full adjustment, participants with high MDS had a 1.73-fold increased risk of all-cause deaths (95% CI: 1.41–2.09) and a 2.01-fold increased risk of CVD deaths (95% CI: 1.49–2.71) compared to those with none-to-low MDS (P for trend = 0.002, and 0.045 respectively).

Subgroup analysis

In Table 5, subgroup analyses show that for individuals ≥ 60, stroke risk increased with higher MDS: ORs of 1.85 (95% CI: 1.27–2.71) for middle MDS and 2.76 (95% CI: 1.57–4.84) for high MDS (P for trend < 0.001). For those < 60, ORs were 1.47 (95% CI: 1.19–1.83) for middle MDS and 1.58 (95% CI: 1.22–2.06) for high MDS (P for trend < 0.001, P for interaction = 0.006). Males had ORs of 2.14 (95% CI: 1.51–3.01) for high MDS (P for trend < 0.001), while females had ORs of 1.64 (95% CI: 1.17–2.30) (P for trend = 0.004, P for interaction = 0.045). LE8, health behaviors, and health factors scores all showed higher stroke risk with higher MDS (P for trend < 0.001). Interaction with MDS was significant for all. Since LE8 interacted significantly with MDS, a mediation analysis was conducted to examine its role in the relationship between MDS and stroke risk. The analysis showed that LE8 had a significant indirect effect, accounting for 26.5% of the relationship (Supplementary Table 4).

Discussion

Our study investigates the relationship between MDS and stroke incidence, utilizing data from NHANES collected between 1999 and 2018. The findings demonstrate that higher MDS significantly correlates with an increased risk of stroke in a dose-dependent relationship. Individuals with high MDS scores (3–5) had a significantly greater likelihood of experiencing a stroke compared to those with low MDS scores (0–1). This positive association remained significant after adjusting for related confounding factors. Previous studies have consistently demonstrated an inverse association between magnesium levels and the risk of stroke and CVD. For instance, recent studies28,29 highlight the importance of both serum magnesium levels and dietary magnesium intake in understanding stroke risk dynamics. For CVD, Helte et al.30 highlighted the protective effects of calcium and magnesium in drinking water against the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke, while Ye et al.31 identified a significant relationship between MDS and CVD mortality in individuals with existing cardiovascular conditions. While these studies focused on serum and dietary magnesium measures, they often faced limitations in capturing an individual’s comprehensive magnesium status due to variability in gastrointestinal absorption, renal excretion, and the impact of medications such as diuretics and PPIs. Serum magnesium, representing only 0.3% of the body’s total magnesium, and dietary intake alone may not effectively reflect overall magnesium deficiency, especially in clinical contexts32,33. In contrast, MDS incorporates multiple factors, including diuretic and PPI use, renal function, and alcohol consumption, to provide a more comprehensive assessment of magnesium status. By integrating these elements, MDS serves as a more reliable indicator of chronic magnesium depletion than isolated serum or dietary measures. Therefore, the introduction of MDS addresses a critical gap in previous research by offering a practical and robust method for evaluating magnesium status9,34,35. Our study builds on previous findings by enhancing the methodology used to assess magnesium status and its relationship with health outcomes. Unlike prior research that primarily examined the association between MDS and general cardiovascular disease outcomes, we uniquely focus on the dose-response relationship between MDS and stroke incidence, positioning stroke as a primary outcome. This approach not only strengthens the predictive utility of MDS but also identifies critical thresholds for clinical intervention. By establishing a clear and quantifiable link between higher MDS and increased stroke incidence, our findings provide a strong foundation for developing targeted prevention strategies and personalized treatment approaches to mitigate the effects of magnesium depletion.

Furthermore, our study demonstrated that higher MDS was associated with increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among stroke patients, likely due to the critical role of magnesium in maintaining vascular health. Magnesium deficiency impairs key protective mechanisms, including the inhibition of platelet aggregation and thrombus formation by regulating platelet activity and reducing thromboxane A2 release36. This anticoagulant effect is crucial in reducing thrombotic risk in stroke patients. Magnesium also acts as a cofactor for antioxidant enzymes like superoxide dismutase and catalase, which neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS). By inhibiting NADPH oxidase, magnesium decreases ROS production and enhances nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability, thus supporting endothelial function. This helps prevent oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction, which are precursors to atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events. Furthermore, magnesium supports mitochondrial function, essential for cellular energy production and survival. Low magnesium levels can impair mitochondrial efficiency, increasing susceptibility to cardiovascular complications37,38. Therefore, low magnesium status, as indicated by higher MDS, likely contributes to increased all-cause and CVD mortality among stroke patients by exacerbating these pathological processes.

In the subgroup analysis, the association between higher MDS and stroke risk was stronger among individuals aged 60 years and older compared to younger participants. This may be explained by the cumulative burden of age-related vascular changes, including arterial stiffness, endothelial dysfunction, and reduced vascular responsiveness, which are further exacerbated by magnesium depletion39. Magnesium plays a vital role in regulating vascular tone, mitigating oxidative stress, and maintaining endothelial function, all of which deteriorate with age, thereby increasing susceptibility to stroke in older adults. Additionally, males showed a stronger association between high MDS and stroke risk compared to females. This disparity may be influenced by sex-specific hormonal factors, such as the vascular effects of testosterone, which could interact with magnesium homeostasis and exacerbate endothelial dysfunction40. Behavioral factors, including higher rates of smoking and alcohol consumption among males, may also amplify the impact of magnesium depletion on stroke risk. In contrast, females may benefit from the protective effects of estrogen, which has been shown to positively influence magnesium metabolism and vascular function41; however, this advantage diminishes after menopause42.

The mediating role of LE8 offers critical insights into the pathways linking MDS to stroke. Magnesium deficiency increases intracellular calcium levels, activating signaling pathways that release pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α43. This inflammatory cascade promotes a prothrombotic state—a hallmark of stroke—and induces oxidative stress that disrupts endothelial integrity, exacerbating vascular dysfunction44. Poor LE8 behaviors, such as inadequate physical activity and unhealthy diets, further aggravate these mechanisms by fostering chronic low-grade inflammation and oxidative stress, compounding vascular damage and accelerating atherosclerosis45. Magnesium also plays a pivotal role in glucose homeostasis, acting as a cofactor for insulin signaling and glucose transport46. Deficiency leads to insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, and impaired glucose uptake, all of which are established contributors to stroke risk. When coupled with suboptimal LE8 behaviors, such as sedentary lifestyles and poor dietary habits, these effects magnify, increasing the likelihood of microvascular damage and cerebral ischemia47. Similarly, magnesium has direct effects on lipid metabolism, lowering LDL cholesterol and triglycerides while increasing HDL cholesterol48. When poor LE8 components such as insufficient sleep and unhealthy diets co-occur with magnesium depletion, dyslipidemia and blood pressure abnormalities are exacerbated, creating a feedback loop of cerebrovascular strain.

Our study establishes a dose-dependent relationship between the MDS and stroke incidence, with a specific focus on stroke as the primary outcome. This fills a critical gap in the literature and supports the development of targeted prevention strategies. We also show that higher MDS scores are linked to increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in stroke patients, highlighting magnesium’s role in vascular health and thrombotic risk. A key strength of our research is the examination of lifestyle factors (LE8) as mediators, offering a comprehensive framework to understand how magnesium depletion interacts with behaviors like physical activity and diet to increase stroke risk. This approach provides a nuanced understanding of how these factors combine to influence stroke risk, underscoring the importance of integrating lifestyle factors with magnesium status in risk assessments.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design precludes the establishment of a causal relationship between magnesium depletion and stroke risk, as associations observed in such studies do not confirm causation. Although we adjusted for multiple confounding factors, residual confounding may still be present due to unmeasured variables and biases, such as those arising from self-reported dietary intake. Furthermore, the reliance on a single time-point measurement limits our ability to capture changes in magnesium status over time. To confirm these associations and elucidate the underlying mechanisms linking magnesium depletion to stroke risk, future research should include prospective cohort studies and randomized controlled trials.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that higher MDS is significantly associated with an increased risk of stroke and higher all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among stroke patients. These findings emphasize the critical role of maintaining adequate magnesium status in cardiovascular health management and suggest the potential utility of MDS as a predictive tool in clinical practice.

Data availability

Data for this study are available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.

References

Hilkens, N. A., Casolla, B., Leung, T. W. & de Leeuw, F. E. Stroke. Lancet 403 (10446), 2820–2836 (2024).

Orellana-Urzúa, S., Rojas, I., Líbano, L. & Rodrigo, R. Pathophysiology of ischemic stroke: role of oxidative stress. Curr. Pharm. Des. 26 (34), 4246–4260 (2020).

Tangvoraphonkchai, K. & Davenport, A. Magnesium and cardiovascular disease. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 25 (3), 251–260 (2018).

Volpe, S. L. Magnesium in disease prevention and overall health. Adv. Nutr. 4 (3), 378S–83S (2013).

DiNicolantonio, J. J., O’Keefe, J. H. & Wilson, W. Subclinical magnesium deficiency: a principal driver of cardiovascular disease and a public health crisis. Open. Heart 5 (1), e000668 (2018).

Dominguez, L., Veronese, N. & Barbagallo, M. Magnesium and hypertension in old age. Nutrients 13 (1), 139 (2020).

Larsson, S. C., Burgess, S. & Michaëlsson, K. Serum magnesium levels and risk of coronary artery disease: Mendelian randomisation study. BMC Med. 16 (1), 68 (2018).

Adebamowo, S. N. et al. Plasma magnesium and risk of ischemic stroke among women. Stroke 45 (10), 2881–2886 (2014).

Lu, J., Li, H. & Wang, S. The kidney reabsorption-related magnesium depletion score is associated with increased likelihood of abdominal aortic calcification among US adults. Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 38 (6), 1421–1429 (2023).

Blaine, J., Chonchol, M. & Levi, M. Renal control of calcium, phosphate, and magnesium homeostasis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 10 (7), 1257–1272 (2015).

Tong, G. M. & Rude, R. K. Magnesium deficiency in critical illness. J. Intens. Care Med. 20 (1), 3–17 (2005).

Fan, L. et al. Magnesium depletion score (MDS) predicts risk of systemic inflammation and cardiovascular mortality among US adults. J. Nutr. 151 (8), 2226–2235 (2021).

Lloyd-Jones, D. M. et al. Defining and setting National goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American heart association’s strategic impact goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation 121 (4), 586–613 (2010).

Lloyd-Jones, D. M. et al. Life’s essential 8: updating and enhancing the American heart association’s construct of cardiovascular health: A presidential advisory from the American heart association. Circulation 146 (5), e18–e43 (2022).

Barragán, R. et al. Influence of demographic and lifestyle variables on plasma magnesium concentrations and their associations with cardiovascular risk factors in a mediterranean population. Nutrients 12 (4), 1018 (2020).

Isiozor, N. M., Kunutsor, S. K., Voutilainen, A. & Laukkanen, J. A. Life’s essential 8 and the risk of cardiovascular disease death and all-cause mortality in Finnish men. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 30 (8), 658–667 (2023).

Curtin, L. R. et al. National health and nutrition examination survey: sample design, 2007–2010. Vital Health Stat. 2 (160), 1–23 (2013).

Johnson, C. L., Dohrmann, S. M., Burt, V. L. & Mohadjer, L. K. National health and nutrition examination survey: sample design, 2011–2014. Vital Health Stat 2 2014 (162), 1–33 (2014).

Chen, T-C., Clark, J., Riddles, M. K., Mohadjer, L. K. & Fakhouri, T. H. I. National health and nutrition examination survey, 2015–2018: sample design and Estimation procedures. Vital Health Stat. 2 2020, 1–35 (2020).

National Center for Health Statistics & Center for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/ (Accessed 12 June 2024).

Parikh, N. S., Merkler, A. E. & Iadecola, C. Inflammation, autoimmunity, infection, and stroke: epidemiology and lessons from therapeutic intervention. Stroke 51 (3), 711–718 (2020).

Iadecola, C., Buckwalter, M. S. & Anrather, J. Immune responses to stroke: mechanisms, modulation, and therapeutic potential. J. Clin. Investig. 130 (6), 2777–2788 (2020).

Reedy, J. et al. Evaluation of the healthy eating index-2015. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 118 (9), 1622–1633 (2018).

ALHarthi, S. S. Y. et al. Association between time since quitting smoking and periodontitis in former smokers in the National health and nutrition examination surveys (NHANES) 2009 to 2012. J. Periodontol. 90, 16–25 (2019).

Hicks, C. W. et al. Peripheral neuropathy and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in U.S. Adults: A prospective cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 174, 167–174 (2021).

Fellegi, I. P. & Sunter, A. B. A theory for record linkage. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 64 (328), 1183–1210 (1969).

Vanderweele, T. J. & Vansteelandt, S. Odds ratios for mediation analysis for a dichotomous outcome. Am. J. Epidemiol. 172 (12), 1339–1348 (2010).

Liu, C. et al. The interaction between estimated glomerular filtration rate and dietary magnesium intake and its effect on stroke prevalence: a cross-sectional study spanning 2003–2018. Front. Nutr. 11, 1395685 (2024).

Sun, P., Wang, Z., Li, B. & Chen, S. Association of dietary magnesium intake with the risk of stroke among adults. Int. Heart J. 64 (6), 1002–1009 (2023).

Helte, E., Säve-Söderbergh, M., Larsson, S. C. & Åkesson, A. Calcium and magnesium in drinking water and risk of myocardial infarction and stroke—a population-based cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 116 (4), 1091–1100 (2022).

Ye, L., Zhang, C., Duan, Q., Shao, Y. & Zhou, J. Association of magnesium depletion score with cardiovascular disease and its association with longitudinal mortality in patients with cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 12 (18), e030077 (2023).

Ismail, A. A. A., Ismail, Y. & Ismail, A. A. Chronic magnesium deficiency and human disease; time for reappraisal? QJM 111, 759–763 (2018).

Zhang, X. et al. The Circulating concentration and 24-h urine excretion of magnesium dose- and time-dependently respond to oral magnesium supplementation in a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Nutr. 146 (3), 595–602 (2016).

Ismail, Y., Ismail, A. A. & Ismail, A. A. The underestimated problem of using serum magnesium measurements to exclude magnesium deficiency in adults; a health warning is needed for normal results. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 48 (3), 323–327 (2010).

Elin, R. J. Magnesium: the fifth but forgotten electrolyte. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 102 (5), 616–622 (1994).

Dong, J. F. et al. Magnesium maintains endothelial integrity, up-regulates proteolysis of ultra-large von Willebrand factor, and reduces platelet aggregation under flow conditions. Thromb. Haemost. 99 (3), 586–593 (2008).

Fedele, G. et al. Impact of inducible nitric oxide synthase activation on endothelial behavior under magnesium deficiency. Nutrients 16 (10), 1406 (2024).

Manju, L. & Nair, R. R. Magnesium deficiency augments myocardial response to reactive oxygen species. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 84 (6), 617–624 (2006).

Ya, J. & Bayraktutan, U. Vascular ageing: mechanisms, risk factors, and treatment strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (14), 11538 (2023).

Eckardstein Av, Wu, F. C. Testosterone and atherosclerosis. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 13, S72–S84 (2003).

Lagranha, C. J. et al. Protective effects of Estrogen against cardiovascular disease mediated via oxidative stress in the brain. Life Sci. 192, 190–198 (2018).

Seelig, M. S., Altura, B. M. & Altura, B. T. Benefits and risks of sex hormone replacement in postmenopausal women. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 23 (5), 482S–496S (2004).

Nielsen, F. H. Magnesium deficiency and increased inflammation: current perspectives. J. Inflamm. Res. 11, 25–34 (2018).

Liu, M. & Dudley, S. C. Magnesium, oxidative stress, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. Antioxidant (Basel) 9 (10), 907 (2020).

Hebib, L. et al. Life’s essential 8 is inversely associated with high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 15024 (2024).

de Sousa Melo, S. R. et al. Participation of magnesium in the secretion and signaling pathways of insulin: an updated review. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 200 (8), 3545–3553 (2022).

Popa-Wagner, A. et al. Dietary habits, lifestyle factors and neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen. Res. 15 (3), 394–400 (2020).

Nartea, R., Mitoiu, B. I. & Ghiorghiu, I. The link between magnesium supplements and Statin medication in dyslipidemic patients. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 45 (4), 3146–3167 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and the staff of NHANES for their dedications and contributions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JJXand SW designed the study and conducted the data analysis. ZKY drafted the manuscript. PW, YLX, JC, and SYZ proposed critical revisions to the manuscript. All included authors made contributions to the manuscript and approved the version submitted. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

NHANES is conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). And the NHANES study protocol was reviewed and approved by the NCHS Research Ethics Review Committee. All participants in NHANES provided written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yuan, Z., Wang, P., Xie, Y. et al. Association of magnesium depletion score with increased stroke incidence and mortality risks in a comprehensive analysis. Sci Rep 15, 6790 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91227-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91227-1