Abstract

This study addressed limitations in calcein-AM-based endothelial viability assays, specifically focusing on pre-stripped DMEK grafts. Key challenges included the suboptimal calcein staining and the incompatibility of the viability assay with subsequent immunofluorescence (IF). Using human corneal grafts, we employed two strategies to optimize calcein staining. Firstly, we improved calcein staining in corneal endothelium by adjusting calcein-AM concentration and diluent, resulting in a threefold increase in fluorescence intensity with 4 µM calcein in Opti-MEM compared to the conventional 2 µM calcein in PBS. Secondly, introducing the trypan blue (TB) post-viability assay greatly reduced non-specific fluorescence, enhancing the contrast of calcein staining. This improvement significantly and importantly decreased both inter-operator’s variability and the time required for viability counting. For the subsequent double IF, an extensive wash is recommended on the fixed and permeabilized graft after the viability assay, which was carried out using Hoechst-Calcein (HC) labeling. The simple technical tips outlined in this study are not only effective for pre-stripped DMEK grafts but may also prove beneficial for other types of corneal grafts, such as PK and DSAEK.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Corneal transplantation is a globally prominent procedure, with penetrating keratoplasty (PK), Descemet’s stripping automatized endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK), and Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) being the predominant techniques, constituting 98.5% of all corneal surgeries in the United States1. DMEK, known for superior outcomes such as enhanced visual recovery, reduced rejection risk, and overall graft survival, has witnessed a surge in popularity2,3,4,5. According to the Eye Bank Association of America’s (EBAA) 2022 report, DMEK rose from 6% of all corneal transplants in 2014 to 32% in 20221. This trend is consistent in Europe, where DMEK accounted for 29.7% of corneal transplants in 20186, and notably in Germany, where DMEK became the predominant keratoplasty procedure, escalating from 53% in 2016 to 65% in 20217.

In recent years, eye banks have increasingly prepared DMEK grafts, aiming to streamline surgery and minimize the risk of procedure cancellations due to potential inoperable DMEK preparations in the operating room. There are two eye bank preparation methods: pre-stripped DMEK grafts, still attached to the cornea, and preloaded grafts completely detached and housed in a cartridge or injector. According to the 2019 report from the European Eye Bank Association (EEBA), pre-stripped DMEK grafts numbered 2476 (9.8%), while preloaded grafts were 349 (1.4%) of total distributed corneal grafts. In 2022, pre-stripped grafts increased to 3610 (13%), and preloaded grafts rose to 698 (2.5%)8,9.

The DMEK graft, comprising corneal endothelial cells (CECs) on a 5–7 µM thick Descemet’s membrane (DM), requires meticulous preparation to avoid DM tears and CEC loss. Given their crucial role in the success of surgery and graft survival, training and validating technicians or surgeons in graft preparation is vital. An accurate method for assessing DMEK grafts is essential to address evolving needs. In addition, ongoing efforts focusing on innovative techniques for peeling and preserving DMEK grafts also require such a tool.

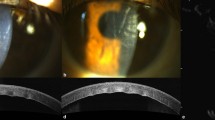

Assessing the quality of corneal grafts in surgeries like PK, DSAEK, and DMEK relies heavily on endothelial quality, a crucial parameter. Endothelial cell density (ECD) serves as the primary criterion for assessing the quality of a corneal graft. The ECD obtained in eye bank, using a specular or light microscope without any cell staining, is currently the sole measure available for clinical use. While this measurement procedure is harmless to cells and tissue, its reliability is yet to be optimized. Viability assay/testing based on Calcein-AM, often co-stained with Hoechst and occasionally ethidium homodimer (Fig. 1A), is the prevailing laboratory technique for evaluating endothelial quality by providing highly reliable ECD10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. Calcein-AM, a cytoplasmic dye specific for living cells (Fig. 1A), permeates plasma membranes due to its lipophilic nature. Initially non-fluorescent, Calcein-AM is transformed into fluorescent calcein within cells through the activity of intracellular esterases. Endothelial viability is determined as the percentage of the surface covered by viable/fluorescent CECs on the DM. To prevent endothelial damage caused by flat-mounting of corneal tissue, images are captured on intact corneas using a fluorescence macroscope, and a 3D reconstructed surface is generated through extended depth of field (EDF) reconstruction19 (Fig. 1B). Hoechst 33,342, staining cell nuclei with a preference for living cells (Fig. 1A), although some dying cells in the early phase can also be found positive18. This dye enables more reliable ECD counting by automating the enumeration of thousands of cell nuclei, compared to ECD counting without dye in eye banks, which typically involves only dozens to hundreds of cells10. The most crucial outcome provided by viability testing is the viable ECD, which proves to be more reliable than the ECD obtained in the eye bank, accurately representing the actual living CECs transplanted in patients17. Viable ECD is calculated by multiplying the ECD obtained from Hoechst staining with the endothelial viability obtained from calcein staining. Ethidium homodimer, a DNA intercalant, stains dead cell nuclei, providing insights into the dying cells during the assay (Fig. 1A). The ECD obtained through Hoechst staining should only include viable cells. However, it’s possible to observe some dying cells that are positive for both Hoechst and Ethidium18. The combined use of Hoechst and ethidium ensures accurate ECD counts by excluding the counting of dead cells.

Endothelial viability assessment and challenges for pre-stripped DMEK grafts. (A) The principle of triple staining HEC involved using Hoechst 33,342, ethidium homodimer, and calcein AM. Hoechst stained cell nuclei blue to facilitate accurate ECD counting. Ethidium stained only dead cell nuclei red. Calcein AM stained all surfaces covered with living cells green, enabling the calculation of viability. The main criterion for an endothelial graft was the viable ECD, which was calculated as ECD x Viability. (B) The determination of endothelial viability on an intact cornea (without cutting or flat mounting) involved staining viable CECs with calcein in light-grey, while dead areas were in dark-grey on a whole human cornea. A Z-stack of 6 or 7 images, separated by a Z-interval of about 600 µM and distributed from the lowest to the highest points of the endothelium, was acquired on the entire endothelial surface. A single composite image (3D reconstructed surface), clear across the entire endothelium, was reconstructed with the extended depth of field (EDF) plugin of ImageJ. The viability in a selected area (8 mm central for this example) was semi-automatically calculated with the CorneaJ plugin of ImageJ. Viability was indicated at the top of the last image. (C) Challenges in assessing the viability of a pre-stripped DMEK graft were depicted. On the left, a pre-stripped DMEK graft stained with calcein AM remained attached with a small area in the center of the cornea, providing a reliable indication of the peel’s quality and the impact of the preservation method. However, inadequate staining contrast posed a significant obstacle to accurately analyzing viability. On the right, the same graft was separated from the corneas and spread on a slide. Calcein-specific fluorescence contrast was restored, but these additional manipulations introduced a considerable amount of endothelial damage, which did not reflect the original quality of the graft. The red arrow indicated the cut made in the graft with the intention for flat mounting.

Corneal graft viability assay presents two major drawbacks. When calcein is used to assess pre-stripped DMEK grafts while still attached to the underlying cornea, the lack of contrast in calcein staining makes viability assessment particularly challenging. Detaching the DMEK graft from the cornea, moving it, and mounting it flat on a slide restores the contrast in calcein staining, but these additional manipulations induce further endothelial damage (Fig. 1C). As a consequence, viability results may no longer accurately reflect the initial state of the endothelium on a pre-stripped graft. This accuracy is essential for a precise assessment of the peeling technique or the method used to preserve the graft in the pre-stripped state. The second major drawback is that immunofluorescence (IF) becomes unfeasible after viability testing due to the residual fluorescence of calcein-AM and ethidium. This limitation leads to the consumption of more corneas, which are valuable human tissues.

The objective of this study was to provide simple yet efficient technical guidance to address these two drawbacks and improve the method for assessing corneal graft quality.

Results

Influence of the concentration and diluent of calcein-AM on its staining and on CECs

-

Influence on staining.

Four different conditions were tested for each of five isolated DMEK grafts. The objective of this step was to increase the intensity of calcein fluorescence in the endothelium. Each graft was divided into four parts and incubated with 2 µM or 4 µM Calcein-AM in PBS or Opti-MEM for 45 min. A drop of BSS was placed on an uncoated slide. The four quarters of the same DM, treated in different ways, were then gently placed with the endothelium facing up using toothless forceps. Excess liquid (BSS) was removed with an ophthalmic sponge, and a few drops of viscoelastic solution (Provisc® OVD) diluted 1:1 in BSS were gently applied on the graft pieces. The slide was immediately photographed under the macroscope. (Fig. 2A1). Fluorescence intensity was assessed by measuring the mean gray value at 6 different viable zones in each part of the DM using Image J. PBS-2 µM was proposed by the manufacturer and literature and considered as the control condition. To eliminate inter-corneal and inter-experiment variances, the fluorescence intensity of the four differently treated DM parts was standardized by making a ratio with their own control: the DM part stained with PBS-2 µM. Statistical analysis revealed significant improvements in all three tested conditions (Opt-2 µM, PBS-4 µM, Opt-4 µM) compared to the control. Opt-4 µM outperformed both PBS-4 µM (p = 0.0196) and Opt-2 µM (p = 0.0049) significantly, demonstrating superior calcein staining efficacy (Fig. 2A2).

Influence of calcein AM concentration and diluent on staining and CECs. (A) Comparison of calcein staining in four different conditions: 2 µM or 4 µM calcein diluted in PBS or Opti-MEM (Opt). (A1) The DMEK graft was separated from the cornea and then cut into four parts. Each part was incubated in one of the four solutions differentiated by calcein concentration (2 or 4 µM) and diluent (PBS or Opt). After incubation for 45 min at RT, the four different parts of the same DMEK graft were spread on the same glass slide and observed simultaneously under the same field using a fluorescence macroscope at a magnification of ×0.8. (A2) The fluorescence intensity of calcein in each of the four parts of the endothelium was measured and then compared. Five different DMEK grafts were used (n = 5). The condition PBS-2 µM was considered as the control condition. The fluorescence intensity of the four parts of each graft was standardized with their respective control. The standardized fluorescence intensity was expressed as Mean +/− SD (Min, Max). One-sample t-test was utilized for statistical analysis, resulting in p = 0.0460 (*) for Opt-2 µM, p = 0.0111 (*) for PBS-4 µM, and p = 0.0096 (**) for Opt-4 µM. (B) Side-effects of using PBS as a diluent: alteration of cell junctions. (B1) Calcein staining of endothelium was performed using dilutions in PBS or Opti-MEM under a microscope with a 10× objective. (B2) Cell junctions were highlighted using IF under a microscope with a 40× objective. The arrowheads indicate dead zones, and the arrows show the cracks that formed between cell islands consisting of several to several dozen CECs.

-

Influence of diluent on CECs.

During the viability test, the corneal endothelium incubated with Calcein diluted in PBS showed cracks between cell islands consisting of several to several dozen CECs (Fig. 2A1,B1). This phenomenon did not occur with Opti-MEM. During the evaluation of cell junctions by immunofluorescence (IF) (Fig. 2B2), we observed disruption of NCAM (basolateral junction) and ZO-1 (apical junction) in the endothelium incubated with PBS. The CECs formed small clusters/islands of cells with large gaps where the cell junctions were completely disrupted. These gaps correspond to the cracks observed with Calcein/PBS staining.

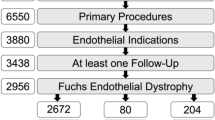

Comparison of viability staining and analysis before and after TB. (A) Viability (Calcein) staining displayed in images. The pre-dissected corneas were numbered from 1 to 10. Two images were acquired for each graft. The left image shows calcein staining before a short TB staining, and the right image depicts the same cornea re-observed after TB. (B,C) Quantitative analysis of TB’s influence on viability assessment. The 20 anonymized images were used for viability counting by six different operators. The viability and counting time were recorded, and results were expressed as Mean +/- SD (Min, Max) above each chart. (B) Comparison of inter-operator variability. For each image, the standard deviation (SD) of the six viabilities from six operators was used as inter-operator variability. The variability/SD of each image was compared before and after TB (n = 10, paired t-test). (C) Comparison of counting time. The counting time used for each image and each operator was compared before and after TB. N = 60, paired t-test.

Reducing undesirable fluorescence by additional TB staining

In this step, we aimed to enhance the endothelium-specific calcein staining quality by minimizing undesirable fluorescence. Calcein-AM 4 µM in Opti-MEM was used for staining the DMEK graft. Following rinsing in BSS, a series of z-photos was taken before and after rapid TB staining, revealing improved contrast in calcein staining. Twenty reconstructed images from ten pre-stripped DMEK grafts were obtained (Fig. 3A). To evaluate the impact on viability counting accuracy and speed, these photos were anonymized and then distributed to six operators for viability analysis. Two main criteria were considered for evaluation: inter-operator variability and viability counting time.

Inter-operator variability was significantly lower (p = 0.0256%) in the “after TB” group (3.5 ± 1.8%) compared to the “before TB” group (6.1 ± 4.3%) (Fig. 3B), representing a 43% reduction. Comparing viability counting time, the “After TB” group (5.6 ± 1.7 min) showed a significant decrease (p < 0.0001%) compared to the “before TB” group (10.3 ± 7.4 min) (Fig. 3C), marking a 46% reduction. The results indicated that the TB-induced improvement in calcein staining not only enhanced accuracy but also significantly expedited the viability counting process, demonstrating its potential for efficiency in corneal endothelial viability assessments.

Other beneficial effects of TB staining for assessing the quality of pre-stripped DMEK grafts. (A) Visualization of the state of peeled DM (graft edge and central attachment). After DMEK graft preparation, it was difficult to see the graft edge and central attachment, which were crucial for assessing the quality of the peeling technique (A. Before TB). TB staining allowed clear visualization of the DM border and central attachment that was not colored blue (A. After TB). At the top, the attachment center was relatively small and well-centered; the edge of the DM was not smooth and regular but did not present any risk of tearing. Below, the attachment was clearly visible as a long band running across the entire diameter of the graft, with a micro-slit (indicated by a yellow arrow) at the edge of the graft. (B) Improving the accuracy of viable ECD counts. Top photos showed standard HEC triple labeling before TB staining. The quality of staining was not optimal, and some areas of confusion were observed where Hoechst was positive but ethidium was negative (indicated by yellow arrows). Bottom photos showed HEC labelling followed by TB staining. All types of fluorescent staining were suppressed in non-viable zones. The staining of Hoechst or calcein in viable zones was improved.

Other advantages of additional TB staining for assessing the quality of pre-stripped DMEK grafts

TB staining effectively highlighted the DM border and attachment zone on the stromal face of the detached DM in pre-stripped DMEK grafts, aiding in evaluating the peeling operator’s technique and graft quality (Fig. 4A). TB enhanced visibility of the central attachment zone, assisting in identifying correct detachment (DM attachment to the central cornea with a small area) (Fig. 4A, top and below center). Additionally, TB staining provided clarity on the DM border (Fig. 4A, right photos). TB’s impact extended to the HEC assay, quenching ethidium staining, improving calcein staining, and enhancing Hoechst staining selectively in viable zones (Fig. 4B). This facilitated accurate ECD counting, focusing on Hoechst-stained viable cell nuclei.

Tips for performing IF after viability assessment. Double IF of NCAM (FITC filter) and ZO-1 (Cy3 filter) was conducted on a DMEK graft that had already undergone viability testing and additional TB staining. (A) IF was performed immediately after HEC staining. (B) IF was performed on methanol-fixed tissue that was rinsed in PBS for 24 h following the HEC staining step. (C) IF was performed on methanol-fixed tissue that was rinsed in PBS for 24 h following the HC staining (without Ethidium).

Realization of double IF after endothelial viability staining

We performed a double IF utilizing primary antibodies to NCAM, labeled with Alexa Fluor™ 488-conjugated secondary antibody, and ZO-1, labeled with Alexa Fluor™ 555-conjugated secondary antibody. These proteins served as specific markers for CECs, each exhibits characteristic subcellular localizations, with NCAM found on basolateral cell junctions and ZO-1 located at apical cell junctions. To avoid confusion with calcein (cytoplasmic) or ethidium (nuclear) staining, we ensured distinct subcellular localizations. Immediate double IF following the HEC viability assay revealed challenges due to persistent cytoplasmic calcein and nuclear ethidium staining, hindering NCAM and ZO-1 observation (Fig. 5A). Prolonged PBS washing resulted in the release of the fluorescent dye (that can be observed using the FITC filter), revealing NCAM staining, while ethidium staining persisted (Fig. 5B). The endothelial viability assay, utilizing the Hoechst and calcein-AM (HC) combination with the omission of ethidium, ultimately enabled the double IF of NCAM and ZO-1 (Fig. 5C).

Discussion

This study addressed two key challenges in evaluating pre-stripped DMEK grafts: improving calcein staining in viability assay and achieving successful IF post-viability assay.

To improve calcein staining, we first studied the influence of calcein concentration and diluent. A notable increase in fluorescence intensity was observed using 4 µM Calcein-AM in Opti-MEM compared to 2 µM in PBS. Bhogal et al. reported that a higher concentration of calcein AM can enhance calcein fluorescence intensity20. In this study, we demonstrated that changing the diluent from a simple buffer to a nutrient-containing culture medium can also increase calcein fluorescence intensity in viable cells. However, we refrained from further increasing the concentration due to potential cytotoxicity from the DMSO present in the stock solution which had a concentration of 4 mM in DMSO, and 0.1% DMSO is considered safe for various cell types21,22. Both the Calcein concentration and the diluent affected fluorescence intensity, with 4 µM being more effective than 2 µM in the same diluent, and Opti-MEM outperforming PBS at the same Calcein concentration. We hypothesized that, as a basal culture medium for cultured CECs, Opti-MEM might enhance Calcein fluorescence by preserving esterase activity in CECs. Among the four tested conditions, Opti-MEM at 4 µM yielded the best results. Incubation in PBS induced crackling patterns in the corneal endothelium, attributed to disrupted cell junctions revealed by ZO-1 and NCAM IF. PBS lacks calcium, which is essential for maintaining CEC junctions23,24,25,26. Our findings suggest that the 0.9% NaCl solution, commonly utilized for ECD counting in European eye banks, may enhance the visualization of corneal endothelial cell contours by weakening junctions. However, it could potentially damage the endothelium during the process.

The second improvement in calcein staining focused on the effects of post-staining with TB. The introduction of TB staining following viability testing provided multifaceted benefits in assessing pre-stripped DMEK grafts. First, it significantly enhanced calcein staining by mitigating undesirable fluorescence, expediting viability counting, and minimizing inter-operator variability and counting time. Second, TB allowed concurrent visualization of the DM border and central attachment. Third, it aids in viable ECD counting in two ways: (1) it limits Hoechst staining to living cells, as TB staining quenches Hoechst fluorescence in the nuclei of dying cells; (2) It prevents undesirable fluorescence from keratocyte nuclei stained by Hoechst, as TB stains the stromal side of DM and blocks any fluorescence from underlying cells. The main undesirable fluorescence in pre-stripped DMEK grafts arises from the direct exposure of the stroma to Hoechst-Calcein AM solution, leading to strong fluorescence staining of keratocytes. TB addressed this issue by staining the stromal side of the detached DM, blocking stromal fluorescence through its quenching properties27,28, and enhancing calcein staining on the endothelial side. Moreover, TB not only masks and quenches the non-specific fluorescence of dead cells but also targets the denuded DM zones on the endothelial side, thereby enhancing the fluorescence contrast of viable CECs. In a surgical context, TB could assist eye bank technicians in perfecting techniques for peeling pre-stripped DMEK grafts, ensuring smooth edges and correct center attachment of DM. Additionally, TB aided in determining ECD through Hoechst staining in viable cells. TB is recognized for entering and staining the nuclei of dying cells, thereby suppressing nuclear fluorescence. Consequently, TB ensures that Hoechst nuclear staining is exclusive to living cells. This simplifies ECD counting and makes ethidium unnecessary. The current viable ECD counting is based on endothelial viability and nuclei/Hoechst + counting in five areas of the entire endothelium10, making the viable ECD an estimation. Counting all nuclei of viable cells would yield a highly accurate viable ECD. Hoechst alone may stain dying cells in their early stages18. However, the addition of TB ensures that Hoechst staining labels only viable cells. This presents the potential to count all viable cell nuclei in the future, once macroscope/microscope technology enables accurate imaging of all Hoechst-stained nuclei in the endothelium. Overall, TB emerged as a valuable tool, not only for optimizing viability and viable ECD assessments but also for offering valuable insights to technicians for their DM peeling technique.

The enhancement in calcein contrast provided by TB is essential for capturing viability images of the DMEK graft while it remains attached to the cornea. Bhogal et al. proposed a curved, transparent DMEK graft imaging chamber that enables calcein imaging of a separated DMEK graft, eliminating the need for additional cutting when placing the graft on a glass slide29. However, this method still requires expertise from a DMEK ophthalmologist to minimize endothelial damage during graft detachment, displacement, and unfolding. Additionally, as the ‘DMEK graft imaging chamber’ is not commercially available, it can be challenging to obtain. Our approach, involving the simple addition of TB, is easy to implement, requires no advanced technical skills, and allows even novice laboratory technicians to reliably assess DMEK graft viability.

IF on flat-mounted corneal endothelium is crucial for detailed CEC status, serving as a valuable tool for evaluating graft preparation methods and corneal graft preservation30,31,32. However, persistent calcein and ethidium staining post-viability testing obstructs commonly used IF filters. We propose a new approach, using double labelling with HC and prolonged rinsing in PBS, allowing subsequent IF. Incubation in PBS effectively removes calcein residues from methanol-fixed grafts. TB addressed the omission of ethidium staining, indicative of dying cells, by resolving confusion in Hoechst staining, specifically focusing on viable cells.

Calcein-AM, initially a non-fluorescent, lipophilic molecule, transforms into hydrophilic and fluorescent calcein upon membrane diffusion into living cells. If the cell membrane remains intact, hydrophilic calcein is retained in the cytoplasm. To facilitate the elimination of hydrophilic, fluorescent calcein, a permeabilized cell membrane is necessary. Methanol, serving as both a fixative and permeabilizer, does not require additional permeabilization. If you used similar fixatives, such as ethanol or acetone, the situation would be the same as methanol fixation, where a simple PBS rinse would be sufficient to remove hydrophilic calcein from inside the cells. In contrast, formaldehyde-fixed cells require an additional step of cell membrane permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100 before PBS rinsing.

Ethidium is a DNA intercalator that can enter a dying cell with a damaged plasma membrane. Once fixed to DNA, it is difficult to remove. We have observed in this study that all cell nuclei are ethidium-stained after the IF procedure following viability testing by HEC. We assume that this homogeneous staining of all cell nuclei is a result of ethidium diffusion from dead cell nuclei to neighboring cells after fixation and permeabilization. In addition, TB staining ensures Hoechst staining exclusively in living cells, rendering ethidium unnecessary. As a result, we propose omitting ethidium during viability testing. If your microscope is equipped with a fourth CY5 (far-red) filter, you can perform double immunostaining by selecting a fluorochrome compatible with the CY5 filter for the second antibody (ZO-1 in this study), in cases where ethidium is required for your viability assay.

The technical tips described in this study for pre-stripped DMEK grafts are theoretically applicable to other types of corneal grafts, including PK and DSAEK grafts. In our laboratory, we routinely apply these tips for endothelial viability assays on whole corneas. Although the improvements are less pronounced than with pre-stripped DMEK grafts, moderate enhancements in calcein and Hoechst staining still aid in viability and ECD analysis. For viability assessments on separate DMEK grafts, the benefits of calcein staining tips are minimal, as unwanted fluorescence from other parts of the cornea is limited. However, the techniques for eliminating fluorescent calcein are applicable to all types of corneal grafts for subsequent immunofluorescence analysis.

In conclusion, we propose assessing the endothelial viability of pre-stripped DMEK grafts through incubation with 4 µM Calcein-AM and Hoechst, both diluted in Opti-MEM, followed by rapid TB staining. This approach offers several advantages: (1) Improved calcein staining, enhancing the reliability and speed of its analysis. (2) Determining DM status and its attachment position. (3) Easy counting of ECD. Additionally, a double IF can be performed after the viability assessing using HC by simply washing the graft in copious PBS for 24 h. Furthermore, we believe that the techniques elucidated in this study are not limited solely to pre-stripped DMEK grafts but are applicable to other graft types, including PK and DSAEK grafts.

Methods

Human corneas and ethical statement

Nineteen human corneas, obtained from donors aged 75 ± 16 (62, 100) years, with a post-mortem interval of 11 ± 6 (4–24) h, were utilized. Stored in organ culture system using culture medium named CorneaMax (EYEMAX00-1 C, Eurobio Scientific) at 31 °C for 19 ± 11 (4–36) days, these corneas were rejected by the Eye Bank of Besancon and Saint Etienne. They were deemed unfit for transplantation and considered as biological waste. BiiO laboratory, authorized by the Ministry of Higher Education, Research, and Innovation of France (Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur, de la Recherche et de l’Innovation, MESRI) under dossier number DC-2023–5458, conducted this research on these human corneal wastes without requiring additional ethical approval. All procedures adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki Principles for biomedical research involving human tissue.

Preparation of pre-stripped DMEK grafts. (A) The trabecular meshwork, indicated by yellow arrows and forming a pigmented line approximately 0.5 wide around the endothelium, was removed with fine-toothed forceps to create a rupture around the extreme periphery of the DM. (B) After confirming DM rupture through simple TB staining, fine, pointed forceps were used to peel back the extreme periphery of the DM in cases where rupture had not occurred. (C) The DM border, approximately 0.5 mm in width, was separated from the corneal stroma along the entire 360° edge of the graft using a curved, flat-tipped separator. (D) The corneal endothelial side was filled with BSS, and the DM was detached from the underlying stroma using straight flat-tip forceps.

Preparation of pre-stripped DMEK grafts

The DMEK grafts were pre-stripped using a Zeiss operating microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), with the cornea positioned on a Vacuum Donnor Cornea Punch block (K20-2019, Barron). Trabecular meshwork excision in a 360° manner was performed using fine-toothed forceps to create a rupture around the extreme periphery of DM (Fig. 6A). 0.4% trypan blue (TB) (T8154, Sigma-Aldrich) was diluted to 0.2% in Balanced Salt Solution (BSS). It was applied to enhance DM rupture visualization, and in cases without rupture, fine forceps were used to peel the extreme periphery of DM (Fig. 6B). Next, a curved, flat-tipped separator (1172, Malosa, BVI Medical) was used to separate the approximately 0.5 mm wide DM border from the corneal stroma along the entire 360° graft edge (Fig. 6C). TB solution could be reapplied if needed, ensuring DM edge separation. The corneal endothelial side was filled with CorneaMax or BSS to prevent DM folding and tearing. The DM was detached from the underlying stroma halfway across the cornea using straight flat-tip forceps, repeating this process three times at 90° intervals to maintain central attachment (Fig. 6D). The DM was then repositioned against the stroma by removing liquid from beneath it using a cellulose sponge.

Endothelial viability assay and optimizations

-

Standard protocol.

A triple labeling protocol, named HEC (Hoechst-Ethidium-Calcein) triple labelling, using Hoechst 33,342, ethidium homodimer, and calcein-AM was devised for assessing corneal endothelial viability and viable ECD10,13,14,17. The HEC mixture, comprising 2 µM calcein-AM (FP-FI9820, Interchim), 4 µM ethidium (FP-AT758A, Interchim), and 5 µg/ml Hoechst 33,342(B2261, Sigma-Aldrich), was prepared in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (SH30028, HyCloneTM). Corneal grafts were gently rinsed in PBS, placed endothelial side up in a concave-shaped support, and incubated in the dark at room temperature (RT) for 45 min with 150 µl of the HEC mixture. After a brief rinse with PBS, the stained endothelium is ready for observation under a fluorescence macroscope.

-

Calcein staining optimizations.

Calcein-AM staining for endothelial viability on pre-stripped DMEK grafts was suboptimal (Fig. 1C). To enhance staining, we aimed to increase specific calcein staining on the corneal endothelium while reducing undesirable fluorescence.

-

1.

We conducted experiments using Opti-MEM phenol red-free (11058021, Gibco) instead of PBS as the diluent for Calcein-AM staining, with the goal of enhancing fluorescence intensity. Additionally, we explored a higher concentration of Calcein-AM (4 µM) compared to the standard 2 µM.

-

2.

To mitigate undesirable fluorescence, pre-stripped grafts were immersed in 0.2% TB (0.4% TB reduced to 0.2% by adding an equal volume of BSS) on the endothelial side. This step was performed after the viability testing. Gentle agitation was necessary to facilitate TB entry between the detached DM and the stroma, resulting in staining of the stromal side of the DM. After a 20-second incubation, TB was removed, and the graft was immersed in Opti-MEM or BSS to eliminate excess TB.

-

Observation.

A fluorescence macroscope (Macro Zoom Fluorescence Microscope System, MVX10, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), equipped with CellSens imaging systems software (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany) and a DP74 color and monochrome camera was utilized, featuring three fluorescence filter sets:

-

1.

DAPI: Ex/325–375 nm, DM/400 nm, Em/435–485 nm (for Hoechst Staining).

-

2.

FITC: Ex/450–490 nm, DM/495 nm, Em/500–550 nm (for calcein staining).

-

3.

CY3: Ex/520–570 nm, DM/565 nm, Em/570–640 nm (for ethidium staining).

For viability measurement on pre-stripped DMEK grafts, a Z-stack of 6 or 7 images, separated by a Z-interval of approximately 600 µM, was acquired across the entire endothelial surface using a 1× objective (MV PLAPo, Olympus) and 0.8× zoom. The EDF plugin of ImageJ reconstructed a single, entirely focused composite image, enhancing accuracy in detecting calcein-positive areas, considering the cornea’s natural curvature (Fig. 1B).

-

Quantitative assessment of the impact of TB on endothelial viability.

Endothelial viability, assessed through calcein images using the CorneaJ plugin in ImageJ, underwent semi-automatic analysis, requiring manual adjustments for accuracy, particularly in cases of suboptimal calcein staining, as previously described19. To quantitatively assess the impact of adding TB staining, we utilized 10 pre-stripped DMEK grafts. Two photos were captured for each graft: one before and another after TB staining. All 20 photos were analyzed by six different operators. Operators, unaware of TB treatment, recorded viability and counting time for each photo. Two criteria were employed for comparison before and after TB.

-

1.

Inter-operator variability It is represented by the standard deviation (SD) of the six endothelial viabilities counted by six different operators for each photo. The goal was to assess whether TB staining could reduce the inter-operator variabilities/SD.

-

2.

Counting time It is the time required to analyze the viability of a photo. An enhancement in the viability/calcein image should lead to a reduction in counting time.

Immunofluorescence (IF) and optimizations

-

Protocol for pre-stripped DMEK grafts.

The IF of flat-mounted corneal endothelium was previously developed and optimized23,33. After viability assay, the pre-stripped DMEK graft underwent gentle washing in BSS. The DMEK graft, being peeled away from the central attachment but still resting on the cornea, was immersed in 25 ml pure methanol fixative for 30 min at RT. After rehydration in PBS, the DM was separated from the cornea and then incubated in blocking buffer (2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 2% goat serum in PBS), at 37 °C for 30 min. A double IF involved incubating the DM in a primary antibody solution [NCAM (Mouse IgG, MAB24081, R&D system) and ZO-1 (rabbit IgG, 40–2200, Invitrogen)] for 1 h at 37 °C. After rinses in PBS, secondary antibody [Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (A-11001, Invitrogen) and Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti-rabbit IgG (A-21429, Invitrogen)] incubation followed for 1 h at 37 °C, supplemented with 5 µg/ml DAPI for nuclear counterstaining. The DM could be cut into parts if necessary, with adjusted antibody solution volumes to avoid waste.

After further rinses in PBS, the DM was delicately spread on a drop of fluorescent mounting medium (NB-23–00158, NeoBio Mount Fluo, NeoBiotech) deposited on a glass slide. For an entire DM, cutting was necessary to prevent folds, and a glass coverslip was placed over it. It was crucial to avoid microbubbles during this process.

-

Optimizations.

-

1.

To eliminate residual calcein fluorescence within CECs, the methanol treated (fixed and permeabilized) endothelium/DM, was immersed in 25 ml PBS overnight at 4 °C.

-

2.

The ethidium staining is visible using the CY3 filter. Therefore, to immunostain proteins at CY3 wavelengths, it is important to avoid using the ethidium stain.

-

Observation.

For IF imaging, an Olympus IX81 fluorescence inverted microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), equipped with CellSens imaging systems software and a monochrome camera (ORCA-Flash 4.0, Hamamatsu), was employed. Three fluorescence filter sets mirrored those used in the microscope:

-

1.

DAPI: Ex/325–375 nm, DM/400 nm, Em/450–490 nm (for DAPI or Hoechst staining).

-

2.

FITC: Ex/460–495 nm, DM/505 nm, Em/510–550 nm (for secondary antibodies combined with Alexa 488 or calcein staining).

-

3.

Ex/520–560 nm, DM/565 nm, Em/572.5–647.5 nm (for secondary antibodies combined with Alexa 555 or ethidium).

-

Precautionary notes.

When performing the IF after the endothelial viability assay on the same graft, it is crucial to take certain precautions during the acquisition of the viability assay photos to prevent any alterations to CEC. Ensure that the endothelium remains moist at all times, and keep the observation and photo-acquisition times within reasonable limits to avoid potential cell phototoxicity. Additionally, refrain from maximizing the intensity of the fluorescence used, whenever possible.

Statistic

GraphPad Prism used for statistical analysis and graph construction; specific tests mentioned in respective figure legends.

Data availability

All data used for this study are contained in this article.

References

EBAA. 2022 Eye Banking Statistical Report. 2(3):p e0008-0012 (The Eye Bank Association of America (EBAA), 2023).

Singh, A., Zarei-Ghanavati, M., Avadhanam, V. & Liu, C. Systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical outcomes of descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty versus descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty/descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea 36, 1437–1443. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0000000000001320 (2017).

Tourtas, T., Laaser, K., Bachmann, B. O., Cursiefen, C. & Kruse, F. E. Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty versus descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 153, 1082–1090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2011.12.012 (2012).

Marques, R. E. et al. DMEK versus DSAEK for Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 29, 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1120672118757431 (2019).

Magnier, F. et al. Preventive treatment of allograft rejection after endothelial keratoplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Ophthalmol. 100, e1061–e1073. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.15154 (2022).

EEBA. Annual directory (28 Edition) of European Eye Bank Association. 9/83 (European Eye Bank Association (EEBA), 2020).

Flockerzi, E., Turner, C., Seitz, B., Collaborators, G. S. G. & GeKe, R. S. G. Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty is the predominant keratoplasty procedure in Germany since 2016: A report of the DOG-section cornea and its keratoplasty registry. Br. J. Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo-2022-323162 (2016).

EEBA. EEBA statistical report of eye banking activity in Europe - Data for 2019 (European Eye Bank Association (EEBA), 2020).

EEBA. EEBA Statistical Report of Eye Banking Activity in Europe - Data for 2022 (European Eye Bank Association (EEBA), 2023).

Pipparelli, A. et al. Pan-corneal endothelial viability assessment: Application to endothelial grafts predissected by eye banks. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52, 6018–6025. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.10-6641 (2011).

Catala, P. et al. Transport and preservation comparison of preloaded and prestripped-only DMEK grafts. Cornea 39, 1407–1414. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0000000000002391 (2020).

Chong, E. W., Bandeira, F., Finn, P., Mehta, J. S. & Chan, E. Evaluation of total donor endothelial viability after endothelium-inward versus endothelium-outward loading and insertion in descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea 39, 104–109. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0000000000002014 (2020).

Kitazawa, K. et al. The existence of dead cells in donor corneal endothelium preserved with storage media. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 101, 1725–1730. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-310913 (2017).

Liu, Y. C. et al. Endothelial approach ultrathin corneal grafts prepared by femtosecond laser for descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 55, 8393–8401. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.14-15080 (2014).

Romano, V. et al. Comparison of preservation and transportation protocols for preloaded Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 102, 549–555. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-310906 (2018).

Straiko, M. M. W. et al. Size and shape matter: Cell viability of preloaded descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty grafts in three different carriers. Cornea 43, 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0000000000003385 (2024).

Gauthier, A. S. et al. Very early endothelial cell loss after penetrating keratoplasty with organ-cultured corneas. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 101, 1113–1118. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-309615 (2017).

SFO. Corneal endothelium. (Chapter 7. Principles of flat-mount endothelial analysis and main markers of corneal endothelial cells). Vol. Chapitre 7 55.e1-e17 (SFO (Société Française d’Ophtalmologie) and Elsevier Masson, 2020).

Bernard, A. et al. CorneaJ: An imageJ Plugin for semi-automated measurement of corneal endothelial cell viability. Cornea 33, 604–609. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0000000000000114 (2014).

Bhogal, M. et al. Real-time assessment of corneal endothelial cell damage following graft preparation and donor insertion for DMEK. PLoS ONE 12, e0184824. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184824 (2017).

Verheijen, M. et al. DMSO induces drastic changes in human cellular processes and epigenetic landscape in vitro. Sci. Rep. 9, 4641. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-40660-0 (2019).

Jamalzadeh, L. et al. Cytotoxic effects of some common organic solvents on MCF-7, RAW-264.7 and human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Avicenna J. Med. Biochem. 4(1), e33453. https://doi.org/10.17795/ajmb-33453 (2016).

He, Z. et al. 3D map of the human corneal endothelial cell. Sci. Rep. 6, 29047. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29047 (2016).

Patel, S. P. & Bourne, W. M. Corneal endothelial cell proliferation: A function of cell density. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50, 2742–2746. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.08-3002 (2009).

Senoo, T., Obara, Y. & Joyce, N. C. EDTA: A promoter of proliferation in human corneal endothelium. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41, 2930–2935 (2000).

Edelhauser, H. F. The balance between corneal transparency and edema: The Proctor Lecture. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 47, 1754–1767. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.05-1139 (2006).

Duerst, R. E. & Frantz, C. N. A sensitive assay of cytotoxicity applicable to mixed cell populations. J. Immunol. Methods 82, 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1759(85)90222-4 (1985).

Johannisson, A., Grondahl, G., Demmers, S. & Jensen-Waern, M. Flow-cytometric studies of the phagocytic capacities of equine neutrophils. Acta Vet. Scand. 36, 553–562. https://doi.org/10.1186/BF03547669 (1995).

Bhogal, M., Balda, M. S., Matter, K. & Allan, B. D. Global cell-by-cell evaluation of endothelial viability after two methods of graft preparation in Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 100, 572–578. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307534 (2016).

Garcin, T. et al. Innovative corneal active storage machine for long-term eye banking. Am. J. Transplant. Off. J. Am. Soc. Transplant. Am. Soc. Transplant Surg. 19, 1641–1651. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.15238 (2019).

Parekh, M. et al. Synthetic media for preservation of corneal tissues deemed for endothelial keratoplasty and endothelial cell culture. Acta Ophthalmol. 99, 314–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.14583 (2021).

Spinozzi, D. et al. The influence of preparation and storage time on endothelial cells in Quarter-Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (Quarter-DMEK) grafts in vitro. Cell Tissue Bank. 21, 615–623. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10561-020-09854-z (2020).

He, Z. et al. Optimization of immunolocalization of cell cycle proteins in human corneal endothelial cells. Mol. Vis. 17, 3494–3511 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the eye bank of Besançon and Saint Etienne for supplying us with scientific corneas (not suitable for transplantation). We would also like to thank Mr Florian BERGANDI for his technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Experiment design: Z.H., G.T. A.S.G and Ph.G.; Performing the experiments: T.S., S.N., Z.H., and P. G.; Data analysis: Z.H., T.S., S.N., P.G., I.A., L.P., S.P., O.D.C., O.B.M. and H.V.; Data interpretation: Z.H., T.S. and S.N.; Manuscript writing: Z.H., T.S., S.N., P.G., I.A. and L.P.; manuscript editing: Z.H., G.T. A.S.G and Ph.G; Funding search: G.T., and Ph.G; All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sagnial, T., Ninotta, S., Goin, P. et al. Optimized laboratory techniques for assessing the quality of pre-stripped DMEK grafts. Sci Rep 15, 7527 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91512-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91512-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

DMEK grafts prepared from corneas stored in TISSUE-C and CARRY-C (deswelling medium) show similar viable endothelial cell density

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Corneal Endothelium Regeneration with Decellularized Porcine Corneal Extracellular Matrix Scaffolds

Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine (2025)