Abstract

To evaluate the tolerance and effectiveness of standard doses (StD) and low doses (LoD) of inhaled antibiotics (IA), in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and chronic bronchial infection (CBI) by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA). Single-center, observational, retrospective, follow-up study of patients with COPD and CBI by PA treated with IA between 2012 and 2021. One year before and one after the first IA dose were analysed. 87 patients were included (86 men) with a mean FEV1(%) of 46.3%. Intolerance to IA was observed in 54 (62.1%), with a median time of 30 days (IQR: 15, 90). Only a higher FEV1(%) was associated with lower probability of intolerance (hazard ratio: 0.98, 95% confidence interval 0.97 to 0.99; p = 0.021). Seven of 15 (46.6%) patients who did not tolerate StD tolerated LoD. Those unable to tolerate LoD also had worse FEV1(%) (38.4% (SD:18.7%) versus 48.1% (SD: 16.4%); p = 0.018). Treatments lasting 6–12 months improved symptoms and reduced PA isolations (− 2.1; P < 0.001) and exacerbations (-1.7, P < 0.001). In 19 patients LoD treatment reduced exacerbations (-2.1, P = 0.003), days of hospitalization (-7.4, P = 0.036) and PA isolations (-2, P = 0.001) with clinical improvement. Antimicrobial resistance was not observed in any case receiving LoD of IA. More than half of our COPD patients treated with IA for CBI by PA presented respiratory intolerance during the first three months related to greater severity of airway obstruction. Treatment with LoD of IA appears to be an effective and safe alternative for some patients unable to tolerate StD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The lower airways of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are often colonised by potentially pathogenic microorganisms (PPMs) and this is associated with increased local and systemic inflammation, more severe respiratory symptoms, increased frequency and severity of exacerbations and accelerated decline in lung function1,2,3,4,5,6. Different PPMs can be associated with chronic bronchial infection (CBI) in COPD, but the CBI by Pseudomonas aeruginosa(PA) has received particular interest because it has a high level of resistance to usual antibiotics, mostly affects more severe patients, and is associated with worst prognosis and increased mortality7,8,9,10,11.

There are currently no randomised controlled trials (RCT) or licenced treatments for CBI by PA in COPD. However, expert opinion recommends the off-label use of inhaled antibiotics (IA), as in patients with bronchiectasis5,7. Limited information is available about the use of IA in COPD and it is important to collect information from real life studies about the effectiveness, tolerance and safety of IA. The few studies published to date were focused on effectiveness, and they associated the use of IA with a decrease in the number and days of hospital admissions due to exacerbations in patients with COPD and CBI12,13,14,15. In them, the most frequent adverse effects were respiratory, but tolerance to IA has not been analysed in a targeted manner, and neither have strategies been proposed to improve tolerance. Given that much higher antibiotic concentrations are achieved in the lungs through inhalation than through oral or intravenous administration16,17, administration of low doses (LoD) of IA is a possible strategy to improve tolerance, but there is no scientific evidence on their effectiveness and safety in COPD.

Methods

Study design and population

This was a single centre, observational, retrospective, follow-up study of patients with COPD and CBI by PA treated with IA in the Hospital Mutua Terrassa (Barcelona, Spain) between January 2012 and January 2021.

The main objective of the study was to analyse tolerance to IA. Secondary objectives were: (a) to identify factors associated with intolerance; (b) to investigate if patients who do not tolerate standard doses (StD) can tolerate LoD; and (c) to evaluate the effectiveness of IA according to the duration of treatment.

The day of the first dose of IA was considered the index date and an observational period of one year before and one after the index date was analysed.

Protocol for inhaled antibiotic administration

IA were initiated after three isolations of PA in the preceding two years despite previous treatment with either 2 weeks of intravenous or 3 weeks of oral antibiotics after each isolation. The initiation was with StD, except in cases in which either possible intolerance due to the presence of signs or symptoms of clinical bronchial hyperresponsiveness was suspected, or if it was considered that IA intolerance might put the patient at high risk due to the severity of COPD. In these cases, LoD were first administered. Intolerance to IA was considered as any clinical adverse effect that conditioned the discontinuation of treatment. The following symptoms were considered: dyspnoea, cough, wheezing, pleural pain, general malaise, dysgeusia and headache. If there was uncertainty about the relationship between the symptoms and the IA, the treatment was stopped and restarted in the stability phase. Reappearance of symptoms with the reintroduction of IA was considered as intolerance. Some patients who initiated StD and showed intolerance were changed to LoD, and in those who initiated LoD and presented intolerance, the IA was either discontinued or changed to a different IA at LoD. The decision depended on the specific case assessment by the treating physician.

We used only commercial IA preparations and defined StD as the doses recommended in the prescribing information of each antibiotic. StD were: colistin 1 million international units (IU) administered with the I-neb delivery device, colistin 2 million IU and tobramycin 300 mg/4 ml administered with the LC PARI PLUS nebulizer, or dry powder colistin 1 capsule (1,662,500 IU) administered with Turbospin® inhaler, all twice daily. Colistin was diluted in sodium chloride 0.9% (ml) 4 ml and administered continuously, while tobramycin was administered one month on/off with not additional dilution. LoD included tobramycin 300 mg/4 ml and dry powder colistin 1 capsule administered both once daily, and various options of nebulized colistin: 1 million IU administered with the LC PARI PLUS nebulizer once or twice daily or 2 million IU once daily, and 1 million IU administered with the I-neb delivery device once daily.

Premedication was carried out with their usual maintenance bronchodilator treatment.

Measurements

During the follow-up period we collected information about discontinuation of IA, date and reasons, possible reintroduction or new IA and dose, as well as the number of PA isolations and its resistance to the antibiotics. Eradication was considered when there was absence of PA growth in three consecutive sputum samples at least one month apart, and possible eradication when there were less than three negative or there was no sputum production. Dyspnoea was measured by the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnoea scale. Exacerbations were defined as an increase in respiratory symptoms requiring treatment with systemic corticosteroids and/or a new course of antibiotics.

Statistical analysis

For the main objective of tolerance of IA, an intention to treat (ITT) analysis was used and all patients who received at least one dose of IA were included, but for the effectiveness analysis a modified ITT analysis excluding only those patients who died during follow-up was performed. The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were compared according to IA tolerance and the duration of treatment. In the case of quantitative variables, Mann-Whitney U or Kruskall Wallis tests were carried out. The Chi-squared test (Fisher test for frequencies < 5) was used for the comparison of categorical variables. Changes in clinical variables during follow up were analysed using Wilcoxon or McNemar tests according to the type of variable.

A backward stepwise Cox regression analysis was performed to identify variables related to IA intolerance. Variables showing an association in the univariate analysis (P < 0.20) were incorporated in the multivariable model. Final variable selection was performed according to the Akaike information criterion (AIC). Time to intolerance was also included in the model. The results were described with hazard ratios (HR), 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-values. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was performed to assess the overall fit of the model.

For all the tests, p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The statistical package R Studio (V4.3.3) was used for the analyses.

Ethical disclosures

The study was approved by the Comité de Etica de Investigación con Medicamentos de la Fundació Assistencial Hospital Mútua Terrassa, Terrassa, Spain (Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Mutua Terrassa Hospital, Terrassa, Spain) on the 22nd of June 2022 and followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The need for informed consent to participate was waived by the same Clinical Research Ethics Committee due to the retrospective design of the study and because the information was obtained from the medical history and was dissociated from the personal identification data making it impossible to identify the subjects, in accordance with the data protection law Nº 2016/679 of the European Parliament. The data were analysed using a database that did not include any patient-identifying information, such as name, medical record numbers, dates of birth, or identification documents.

Results

Population

A total of 87 COPD patients with CBI by PA were treated with IA. Of these, 86 (98.8%) were men, with a mean age of 75.7 (standard deviation [SD]: 7.8) years. The mean post-bronchodilator FEV1(%) was 46.3% (SD: 19.4%) and 55 (63.2%) had bronchiectasis (Table 1).

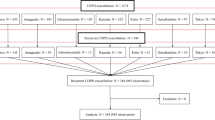

Tolerance to inhaled antibiotics

Forty-nine (56.3%) patients initiated treatment at StD and 38 (43.7%) at LoD. The IA used were: nebulized tobramycin 56 (64.4%) (36 StD and 20 LoD), nebulized colistin 26 (29.9%) (10 StD and 16 LoD) and dry powder colistin 5 (5.7%) (2 StD and 3 LoD). Of those who initiated StD, 28 of 49 (57.1%) showed intolerance and 15 were changed to LoD; 7 (46.6%) tolerated the LoD and continued until the end of follow-up. In the group who initiated LoD, 26/38 (68.4%) showed intolerance and 10 were changed to another IA at LoD, but none tolerated (Fig. 1).

In all, initial intolerance to IA was observed in 54 (62.1%) patients (groups 3 and 4 of Fig. 1). The most frequent symptoms of intolerance were dyspnoea in 52 (96.3%) and cough in 11 (20.4%) patients, and the median time to the appearance of intolerance was 30 days (interquartile range [IQR]: 15, 90). In 14 (16.1%) patients intolerance occurred after 3 months of treatment. Figure 2 shows the timeline for initial intolerance.

In the global analysis of tolerance, 47 (54%) patients presented intolerance at different doses or time points (groups 6, 7, 8 and 9 of Figs. 1) and 40 (46%) tolerated the treatment either initially at StD or LoD or after dose reduction (groups 1, 2 and 5 of Fig. 1). The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients according to tolerance to IA are shown in Table 1. Only FEV1(%) was significantly lower in patients who did not tolerate the IA (42.0% (SD:19.8%) versus 51.4% (SD: 18.0%); p = 0.002). In a multivariate analysis only a higher FEV1(%) was independently and significantly associated with a lower probability of intolerance (HR: 0.98, 95%CI 0.97 to 0.99; p = 0.021). The final model was well calibrated, with a p-value of 0.742 according to the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. Tolerance and intolerance symptoms were similar for the three antibiotics used.

Nineteen patients showed tolerance to LoD (groups 2 and 5 in Figs. 1), 10 with tobramycin every 24 h and 9 with nebulized colistin with different LoD regimens. The median treatment time was 365 days (IQR: 308, 365). On univariate analysis, FEV1(%) was again significantly lower in patients unable to tolerate LoD (38.4% (SD:18.7%) versus 48.1% (SD: 16.4%); p = 0.018), as was oxygen saturation (93.5% (SD: 2.7%) versus 95.2% (SD: 2.2%); p = 0.014) (Table 2).

Effectiveness and safety of inhaled antibiotics

Eleven patients (12.6%) died during the first year after starting IA. Seven of these patients died while treated with IA, five at LoD, with all showing good tolerance. The causes of death were respiratory in 5 (3 COPD exacerbation, 1 influenza and 1 pneumothorax), 1 due to multiple myeloma and 1 of unknown cause.

In the analysis for effectiveness, patients were divided into three groups according to the duration of treatment (Table 3). The effectiveness of IA ranged from no significant effect in cases with shorter treatment to a significant improvement in symptoms (sputum production and purulence), the number of PA isolations and the frequency of exacerbations with longer treatments (Table 4). The rates of eradication and possible eradication did not significantly differ among groups (45.4%, 57.1% and 56.8% for the shortest to the longest treatment groups; p = 0.815). Although a worsening of FEV1(%) was observed in the group that received IA for 1–6 months, this worsening was not observed in the group treated for more than 6 months.

Likewise, treatment with IA at LoD in 19 patients showed a decrease in the number of exacerbations and days of hospital admission, as well as improvement in clinical and microbiological parameters (Table 5). In terms of safety, no antimicrobial resistance to the IA or any evidence of a significant worsening in FEV1(%) was observed in any patient receiving LoD of IA.

Discussion

More than half of our COPD patients who initiated IA treatment at StD initially presented intolerance, with this value increasing to 62% when including patients with intolerance to IA at LoD. The main symptoms of intolerance were dyspnoea and cough during the first 3 months of treatment, being most common after one month, with intolerance appearing later in 16% of patients. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study analysing the use of IA in patients with COPD and CBI by PA and is the first to specifically analyse intolerance to IA and the factors associated in these patients. It also evaluated the use of LoD of IA as an alternative treatment for patients unable to tolerate StD or considered at high risk of intolerance.

Respiratory symptoms such as dyspnoea and cough were the most common cause of treatment discontinuation in our study, as previously reported13,14,15. In fact, the possibility of bronchospasm after IA is warned in the technical specifications of the commercial IA preparations. These symptoms could be related to direct irritation by the drug, as well as to the changes that these products can produce in the osmolarity of the respiratory tract18.

The efficacy and safety of IA have been assessed in patients with bronchiectasis in several studies; however, the few studies that have analyzed their impact on COPD basically focused on their effectiveness19. These studies described lower rates of intolerance compared to ours, although with a similar time of onset, being mainly during the first three months of treatment. Monton et al. reported that 21% of 53 patients with COPD and CBI by PA treated with nebulized colistin presented intolerance during the first three months and 9% after this period14. However, they excluded an unspecified number of patients with a decrease in FEV1 of 200 mL and 12% right after the first dose of IA, while our protocol contemplates performing spirometry after 1–2 weeks. This may have increased our overall rate of intolerance as patients with a possible immediate decrease in FEV1were not detected. In the study including the largest number of patients with COPD on IA, 25% of the patients presented similar adverse respiratory events in the first three months, after a median of 22.5 days15. However, it should be taken into account that this multicentre study included different IA and at various doses, and the IA protocols used were not described and very likely significantly differed among the various study centres. In another study, Bruguera et al.. did not include patients who received less than 3 months of treatment with colistin for CBI by PA, and thus initial intolerance, which was the most frequent in our study, was not reported13. Despite this limitation, 4 of 36 (11%) patients presented bronchospasm after 3 months of treatment.

In patients with bronchiectasis, a meta-analysis of RCT showed that treatment with IA was associated with wheezing and bronchospasm in up to 22% of cases20,21. However, some studies were of short duration, and thus, longer-term effects were unknown, and in all of these studies the lung function of the patients was higher, with a mean FEV1(%) > 50%. Likewise, a study on the efficacy and safety of dry powder IA in patients with bronchiectasis found that having comorbid COPD was an independent risk factor for intolerance with an OR of 2.322. The present study showed that patients who did not tolerate IA had a lower baseline FEV1(%). This relationship of worse tolerance in relation to greater severity of airway obstruction could explain the better tolerance to IA in patients with bronchiectasis. Interestingly, this same fact can make the management of patients with COPD and CBI by PA difficult, because both the frequency of CBI and the prevalence of PA increase as the severity of COPD increases23,24. Our results suggest that close clinical and spirometric monitoring should be recommended in patients with COPD, especially during the first month of IA treatment, and in case of clinical worsening in patients receiving long-term IA, the possibility of late intolerance should also be considered.

Our study showed that in patients with COPD and CBI by PA treatment with various IA with a median duration of one year was associated with clinical improvement and decrease of exacerbations, as in previous studies16,17,18. The decrease in hospital admissions was not statistically significant, probably due to the small sample size and the low number of admissions during follow-up.

A particularly novel aspect of our study was the use of IA at LoD in COPD, a practice that has already been used in other diseases, such as cystic fibrosis (CF) or ventilator-associated pneumonia25,26,27. Although the numbers were small, almost half of the patients who did not tolerate StD were able to tolerate LoD, and in the latter cases, efficacy was demonstrated by the presentation of the same parameters as those obtained with StD. A possible concern when using LoD of antibiotics is the possible appearance of antimicrobial resistance, but this was not detected in any of our patients during treatment with LoD. This result is similar to that of some previous studies on colistin at LoD in CF, including a study using monthly on/off administration in which no antimicrobial resistance was detected after 6 months25,26. Patients who did not tolerate LoD were again those with a lower FEV1(%), but no worsening of FEV1 was observed in those who tolerated LoD. These results are important since they describe a problem in clinical practice such as intolerance to IA at conventional doses, which, according to our results, occurs in more than half of the COPD patients with CBI by PA. In these cases, the administration of LoD could be tested with close monitoring. On the other hand, the option of starting treatment with LoD in patients with very severe airflow limitation may be considered and, depending on the evolution, the dose might be increased or maintained if proving effective, although more studies are needed. Interestingly, patients who did not tolerate LoD of an IA were also unable to tolerate another IA also at LoD. This suggests that while the type of IA could influence tolerance, the most relevant factor was impaired FEV1 in our study using colistin and tobramycin.

Our study has several limitations: first, it was an observational, retrospective, single-centre study that did not include a control group. The small number of patients in the subgroups of analysis reduced statistical power and limited the number of variables included in the multivariate analysis. On the other hand, being a single centre study limits its external validity. Therefore, our findings have to be analyzed with caution and must be validated in future prospective and multicenter studies with a larger number of patients. Another limitation derives from the definition of intolerance based only on patients’ symptoms without objective spirometric data. However, the decision of IA discontinuation in routine clinical practice is mainly based on clinical symptoms. Finally, most patients received the IA via a nebulizer, and therefore, the results cannot be extrapolated to other delivery systems such as dry powder or other novel inhaled antibiotic formulations that are being developed28.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study confirms that IA improve symptoms and reduce exacerbations in patients with COPD and CBI by PA. However, more than half of the patients presented intolerance during the first three months of treatment, mainly at one month, and this intolerance was related to greater severity of airway obstruction. The administration of LoD of IA was an effective and safe alternative for some patients who did not tolerate StD. The initial use of IA at LoD can be considered in patients with severe airflow obstruction in whom the risk of intolerance is highest. Nevertheless, these results should be confirmed in prospective, well- designed, interventional studies.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Matkovic, Z. & Miravitlles, M. Chronic bronchial infection in COPD. Is there an infective phenotype? Respir Med. 107 (1), 10–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2012.10.024 (2013). Epub 2012 Dec 4. PMID: 23218452; PMCID: PMC7126218.

Desai, H. et al. Bacterial colonization increases daily symptoms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc 11(3):303-9. (2014). https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201310-350OC. PMID: 24423399.

Braeken, D. C. et al. Sputum microbiology predicts health status in COPD. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 11, 2741–2748. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S117079 (2016). PMID: 27853361; PMCID: PMC5106218.

Martínez-García, M. Á. et al. Chronic Bronchial Infection Is Associated with More Rapid Lung Function Decline in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc 19(11):1842–1847. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.202108-974OC. PMID: 35666811.

Martinez-Garcia, M. A. & Miravitlles, M. The impact of chronic bronchial infection in COPD: A proposal for management. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 17, 621–630. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S357491 (2022). PMID: 35355582; PMCID: PMC8958724.

Lopez-Campos, J. L. et al. Current challenges in chronic bronchial infection in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Clin. Med. 9 (6), 1639. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9061639 (2020). PMID: 32481769; PMCID: PMC7356662.

De la Rosa Carrillo, D. et al. Consensus document on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic bronchial infection in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch. Bronconeumol. 56 (10), 651–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arbres.2020.04.023 (2020). Epub 2020 Jun 13. PMID: 32540279.

Murphy, T. F. et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 177 (8), 853–860. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200709-1413OC (2008). Epub 2008 Jan 17. PMID: 18202344.

Choi, J. et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection increases the readmission rate of COPD patients. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 13, 3077–3083. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S173759 (2018). PMID: 30323578; PMCID: PMC6174684.

Eklöf, J. et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and risk of death and exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an observational cohort study of 22 053 patients. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 26 (2), 227–234 (2020). Epub 2019 Jun 22. PMID: 31238116.

Martinez-García, M. A. et al. Long-Term risk of mortality associated with isolation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in COPD: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 17, 371–382 (2022). PMID: 35210766; PMCID: PMC8858763.

Dal Negro, R. et al. Tobramycin nebulizer solution in severe COPD patients colonized with Pseudomonas aeruginosa: effects on bronchial inflammation. Adv. Ther. 25 (10), 1019–1030. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-008-0105-2 (2008). Erratum in: Adv Ther. 2008;25(12):1379. PMID: 18821068.

Bruguera-Avila, N. et al. Effectiveness of treatment with nebulized colistin in patients with COPD. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 12, 2909–2915. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S138428 (2017). PMID: 29042767; PMCID: PMC5634377.

Montón, C. et al. Nebulized colistin and continuous Cyclic Azithromycin in severe COPD patients with chronic bronchial infection due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A retrospective cohort study. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 14, 2365–2373 (2019). PMID: 31802860; PMCID: PMC6802559.

De la Rosa Carrillo, D. et al. Effectiveness and safety of inhaled antibiotics in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A multicentre observational study. Arch. Bronconeumol. 58 (1), 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arbres.2021.03.009 (2022). Epub 2021 Mar 19. PMID: 33849721.

Le Conte, P. et al. Lung distribution and pharmacokinetics of aerosolized tobramycin. Am Rev Respir Dis 147(5):1279-82. (1993). https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm/147.5.1279. PMID: 8484643.

Geller, D. E. et al. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of aerosolized tobramycin in cystic fibrosis. Chest 122(1):219 – 26. (2002). https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.122.1.219. PMID: 12114362.

Vélez, M. et al. Safety and tolerability of inhaled antibiotics in patients with bronchiectasis. Pulm Pharmacol Ther Feb;72:102110. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pupt.2022.102110. PMID: 35032638.

Cordeiro, R. et al. The Efficacy and Safety of Inhaled Antibiotics for the Treatment of Bronchiectasis in Adults: Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Chest 166(1):61–80. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2024.01.045. PMID: 38309462.

Yang, J. W. et al. Efficacy and safety of long-term inhaled antibiotic for patients with noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: a meta-analysis. Clin. Respir J. 10 (6), 731–739. https://doi.org/10.1111/crj.12278 (2016). Epub 2015 Mar 2. PMID: 25620629.

Murray, M. P. et al. A randomized controlled trial of nebulized gentamicin in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 183 (4), 491–499. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201005-0756OC (2011). Epub 2010 Sep 24. PMID: 20870753.

Martínez-García, M. Á. et al. Inhaled dry powder antibiotics in patients with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: efficacy and safety in a real-life study. J Clin Med 9(7):2317. (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9072317. PMID: 32708262.

Martínez-García, M. Á. et al. Risk Factors and Relation with Mortality of a New Acquisition and Persistence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in COPD Patients. COPD 18(3):333–340. doi: 10.1080/15412555.2021.1884214. Epub 2021 May 3. PMID: 33941014. (2021).

Miravitlles, M. et al. Relationship between bacterial flora in sputum and functional impairment in patients with acute exacerbations of COPD. Study Group of Bacterial Infection in COPD. Chest 116(1):40 – 6. (1999). https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.116.1.40. PMID: 10424501.

Hodson, M. E., Gallagher, C. G. & Govan, J. R. A randomised clinical trial of nebulised tobramycin or colistin in cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J 20(3):658 – 64. (2002). https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.02.00248102. PMID: 12358344.

Riethmüller, J. et al. Sequential inhalational Tobramycin-Colistin-Combination in CF-Patients with chronic P. Aeruginosa Colonization - an observational study. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 39 (3), 1141–1151. https://doi.org/10.1159/000447821 (2016). Epub 2016 Aug 31. PMID: 27576543.

Zhu, Y. et al. European investigator network for nebulized antibiotics in Ventilator-Associated pneumonia (ENAVAP). nebulized colistin in Ventilator-Associated pneumonia and tracheobronchitis: historical background, pharmacokinetics and perspectives. Microorganisms 9 (6), 1154. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9061154 (2021). PMID: 34072189; PMCID: PMC8227626.

Islam, N. & Reid, D. Inhaled antibiotics: A promising drug delivery strategies for efficient treatment of lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs) associated with antibiotic resistant biofilm-dwelling and intracellular bacterial pathogens. Respir Med. 227, 107661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2024.107661 (2024). Epub 2024 May 8. PMID: 38729529.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Luis Máiz Carro, from the Chronic Bronchial Infection Unit of the Pneumology Department of the Ramón y Cajal Hospital (Madrid, Spain), for his expert review of the manuscript.

Funding

This study has not received specific grants from public sector agencies, pharmaceutical industry, the commercial sector, or non-profit organizations. The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.C., A.N., C.E. and M.M. contributed to the study conception and design. R.C., A.N., M.L. and A.H. collected the database and performed the tables. C.E. performed the statistical analysis and contributed to the tables. R.C. and M.M. were the major contributors in writing the manuscript and performing the figure. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.The authors declare that they have not used any artificial intelligence tools in the production of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Marc Miravitlles has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Cipla, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, Kamada, Takeda, Zambon, CSL Behring, Specialty Therapeutics, Janssen, Grifols and Novartis, consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Atriva Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, BEAM Therapeutics, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, CSL Behring, Ferrer, Inhibrx, Menarini, Mereo Biopharma, Spin Therapeutics, Specialty Therapeutics, ONO Pharma, Palobiofarma SL, Takeda, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Zambon, Zentiva and Grifols and research grants from Grifols. Annie Navarro has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Chiesi, Cipla, GlaxoSmithKline and Zambon. Miguel Ángel Leal has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca and Chiesi.Roser Costa has received speaker fees from Novartis, AstraZeneca, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Zambon and Bial. The remaining authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Annie Navarro has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Chiesi, Cipla, GlaxoSmithKline and Zambon.

Miguel Ángel Leal has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca and Chiesi.

Roser Costa has received speaker fees from Novartis, AstraZeneca, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Zambon and Bial.

The remaining authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Costa, R., Navarro, A., Leal, M.Á. et al. Tolerance and effectiveness of inhaled antibiotics at standard or low doses in COPD patients with chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa bronchial infection. Sci Rep 15, 8773 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91763-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91763-w