Abstract

Tobacco smoke contains many toxic heavy metals that cause adverse effects in humans. The association between second-hand smoke (SHS) and the toxic metals accumulated in pregnant women are still unclear. We measured trace element levels in the sera of pregnant women exposed to SHS and compared the data to those of unexposed pregnant women. Moreover, the data were contrasted with the anthropometric measurements (birth weight, birth length, and head circumference) of their newborn babies after delivery. Two groups of pregnant women were voluntarily recruited, and their blood samples were collected. Then, ten trace elements were measured in their sera, and the data were statistically analyzed using R version 4.0.3 software. The serum trace elements in the smoking subjects were higher than those of the non-smokers, but the difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). The SHS had adverse effects on some trace elements on the smokers’ sera. The concentrations of Cr and Ni in mothers exposed to SHS (32.85–51.25) were significantly higher than those in the mothers unexposed to SHS (28.26–44.80; p < 0.05). The study found that some trace elements significantly affected the anthropometric measurements of infants born to mothers who were exposed to SHS (p < 0.05). Exposure of pregnant women to cigarette smoke had adverse effects on their newborns’ body weights. The mothers who smoked had babies with lower weights. Also, the exposure to cigarette smoke might have caused some of the disorders during their pregnancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nearly 20% of the world’s population smoke tobacco products, and the global statistics predict that the number of smokers may rise to 1.6 billion by the end of 20251. In 2019, tobacco smoking was associated with 8.71 million deaths worldwide, comprising 13.6% of all human deaths2. Tobacco smoke contains approximately 7,000 chemicals and elements, at least 69 of which are known to be carcinogenic. Also, smoking cigarettes is responsible for about 30% of all deaths due to cancer of various bodily organs worldwide2,3.

Consuming tobacco products and smoking cigarettes during pregnancy are the major modifiable risk factors associated with adverse effects on the babies born to smoking mothers. Exposure to tobacco smoke, also referred to as second-hand smoke (SHS), can be due to direct exposure to people who smoke cigarettes. This is responsible for approximately 1% of all cases of human deaths worldwide. Second-hand smoke usually lingers indoors for hours and may become more toxic over time, depending on the frequency and quality of certain environmental variables. These include airflow patterns, ventilation, and physical distance between nonsmokers and smokers4,5, which can affect the intensity and duration of exposure to the smoke. Exposure to SHS can also occur when non-smokers inhale the smoke blown out by smokers at close distance, or if tobacco products are being burnt on such devices as hookahs. In this context, homes and work places are the main areas where people may be exposed to SHS6.

Health disorders associated with cigarette smoking are attributed to the inhalation of various toxic substances present in the smoke, including nitrosamines, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, volatile organic compounds, and other chemicals7. Arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), and lead (Pb) are among the most common trace elements linked to adverse health effects in cigarette smokers8. These are known to be carcinogenic in humans by the International Agency for Research on Cancer9. Trace heavy metals with relative high densities can have adverse effects on the tissues of human, animals and plants10. Although some heavy metals, such as iron (Fe), zinc (Zn), and copper (Cu) are essential for human metabolic activities, their concentration can become harmful to human health when levels exceed a certain threshold11. The resultant health issues may include neurological, cardiovascular, renal injuries, and endocrine disorders, in addition to cancers and infertility risks12.

Accumulation of trace elements in the reproductive tissues of men and women can lead to the infertility13. Also, trace elements, such as As, Cd, and Pb, are associated with increased oxidative stress, cell apoptosis, endocrine disruption, and epigenetic damages14. Inhalation of SHS during pregnancy increases the risk of premature birth, and low birth weight, and is associated with a high incidence of maternal anemia16,16. Limited studies have been conducted on the adverse effects of SHS in pregnant women. In this context, the impact of SHS in the Iranian pregnant women has not been studied. Therefore, this study was planned to investigate the adverse effects of SHS on the pregnant women residing in Kermanshah province, Iran.

Materials and methods

Study population

This study was designed as a case-control research project aimed at investigating the effects of SHS on pregnant women versus a similar but unexposed population. The study protocols including the consent form were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran (approval code: IR.KUMS.REC.1402.510).

Determination of sample size

The required sample size of 111 subjects was determined based on the following formulas 1 and 2, and our experience from a former study17. See reference 1 in the footnote below.

Where \(\:{\varvec{n}}_{1}\) is the sample size in the smaller group, r is the ratio of the size of the larger group to the smaller group, σ is the standard deviation of the considered variable, and d is the smallest difference between the means of the two groups that is considered significant. \(\:1-\varvec{\beta\:}\:\)and \(\:\varvec{\alpha\:}\:\)are the values corresponding to the power and type I error, respectively. The parameter \(\:\varvec{d}/\varvec{\sigma\:}\) is the effect size. For roughly equivalent selection of both groups (r ≅ 1),\(\:\:\varvec{\alpha\:}=\text{0.05,\:}1-\varvec{\beta\:}=\text{0.8}\) and an effect size of 0.6, the minimum required sample size is 44 subject in each group.

Taking into account a possible dropout rate of about 13%, in the present study we included 57 mothers for the smaller group.

Subject’s recruitment & grouping

The pregnant women referred to a local obstetric ward were notified of the impending research project, and they were invited to join the study as subjects. From among the pregnant women who indicated their interest in joining the study, we began recruiting the eligible ones until we reached 111 subjects, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. After attending an orientation session and personal interviews, these women reviewed the study protocol and signed an informed consent letter before being officially included in the study. These otherwise healthy subjects were divided into two groups of exposed versus non-exposed pregnant women to SHS. They were entered in a checklist anonymously by codes under demographic classification as age, level of education, employment status, number of previous births, smoking status, history of abortion, and BMI.

Data collection

At each experimental session two of the investigators were assigned to interview the subjects for that session, collect their demographic data in a checklist, and draw the 3-ml venous blood samples after interview and grouping of the women at Motazedi and Imam Reza Hospitals, in Kermanshah, Iran. Also, after delivery of their babies, the physical features of each newborn (birth weight, birth length, and head circumference) was recorded in an approved checklist by two attending physicians specialized in obstetrics and gynecology that were fully familiar with the women.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria required that each pregnant woman had lived in Kermanshah region for at least five years. They had the choice of being exposed to SHS or not at all at home, or work place or both. Also, an attempt was made to select pregnant smokers and non-smokers from a geographic area with a similar lifestyle. Pregnant women with diabetes, chronic diseases or exposure to industrial sites, and those who had lived in that region for less than 5-years were excluded from the study. The demographic variables of these women were recorded in a checklist. Finally, the birth weight, length, and head circumference of each newborn baby were carefully taken and recorded shortly after birth.

Processing sera for trace elements

Before delivery, a venous blood sample (2-ml) was collected from each of the women, and was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. Next, the serum samples were transferred to micro-centrifuge tubes, labeled with each patient’s code and stored in a freezer at -20 °C until further processes. The serum samples (1-ml each) were mixed with 3-ml nitric acid (Suprapure HNO3, 65%, Merck, Germany) and 1-ml hydrogen peroxide (H2O2; 30%), and were incubated in a Bain-Marie water bath at 98 °C17 for about six hours. Briefly, this process was performed in three steps as outlined below: Step 1: 3-ml nitric acid was added to each of the serum samples and kept at room temperature for 24 h, allowing for a slow digestion process. Step 2: 1-ml hydrogen peroxide was added to the samples and incubated in a Bane Marie water bath (TW12, Julabo, Germany) until the digestion process was complete. The clear solution point became cloudy after six hours, which was brought to a volume of 10-ml by adding distilled water. Step 3: The samples were then injected into an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrophotometer (ICP-MS; Perkin Elmer-7300 DV; Florida, USA) for the determination of the trace elements in the serum samples.

Statistical analyses

For quantitative variables, we first checked the data for normal distribution using the Shapiro-Wilks’ test. Then, we used the data means and standard deviations to analyze the variables. If the date were not normally distributed, we used the median and interquartile ranges. For qualitative variables, we reported the frequency numbers and percentages. To examine the relationship between quantitative variables within binary variable levels, we used Student’s t-test and Mann-Whitney’s U test. For multi-class qualitative variables, we used the analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Kruskal-Wallis tests. Next, we used Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation coefficients, respectively, for normally and non-normally distributed data. These were presented using a heat plot format. Multivariate regression analysis was used to examine the simultaneous effect of trace metal concentrations versus the weight, height and head circumference of the babies. These data were separated into two groups: those exposed or not exposed to SHS. Also, multiple regressions were performed to examine the effect of SHS exposure versus trace element concentrations in the presence of other variables. The statistical significance for all tests was set at p ≤ 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed, using R software, version 4.0.3 (Posit, PBC; Vienna, Austria).

Results

Descriptive statistics and univariate analyses

The data, as presented in Table 1, indicated that out of 111 pregnant women who were included in the study, 61.26% were exposed to SHS. The clinical and demographic characteristics of the pregnant women, and their babies versus those unexposed to SHS are reflected in Tables 1 and 2. Based on the statistical normality test, the data for age, body mass index (BMI), newborn babies’ weight, length, and head circumference were normally distributed (p > 0.05). The women’s mean age who were exposed to SHS (32.250 ± 5.42) was significantly higher than those who were not exposed to SHS (28.163 ± 6.82 y) (p < 0.001). In addition, the mean weight of the babies whose mothers were exposed to SHS (3351.47 ± 495.20 g) was significantly higher than those of the babies whose mothers were not exposed to SHS (3161.63 ± 463.15 g) (P = 0.046).

Most mothers who were exposed to SHS had university education (41.2%), while most unexposed mothers had high school education (55.8%). The difference between the two groups based on education was statistically significant (P = 0.028). A large percentage of mothers who were not exposed to SHS (88.4%) had normal delivery and only 11.6% of them required cesarean section (p < 0.001). Also, only 7% of mothers unexposed to SHS smoked, while 50% of those who were exposed to SHS were also smokers. The difference between the two groups was statistically significant (p < 0.001). As reflected in Table 3, the concentrations of Cr and Ni in the mothers exposed to SHS were significantly higher than those of the unexposed mothers (Cr: 32.85 ± 14.57 Vs Ni: 51.25 ± 22.27; or Cr: 28.26 ± 9.27 Vs Ni: 44.80 ± 12.10). The differences in the serum levels of other trace elements between the two groups were not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

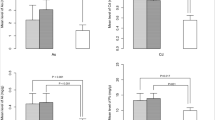

Correlation analyses

Based on the correlation coefficients of the quantitative variables for the mothers exposed to SHS (Fig. 1), the correlation coefficient between Fe and the baby’s head circumference (r= -0.252; P-value = 0.038), between Cu and the baby’s weight (r=-0.393, P-value = 0.001) and between Cu and the baby’s head circumference (r=-0.342; P = 0.004) were weak but significant. Conversely, there was no significant correlation between the demographic and clinical characteristics of the same group of mothers (p > 0.05). With respect to the qualitative variables for the mothers unexposed to SHS (Fig. 2), there was a weak but significant correlation only between the serum level of Cu in mothers and the baby’s head circumference (r= -0.330; P = 0.031). In these mothers, there was a significant correlation between abortion history and their babies’ length (P = 0.028). The mean length of the babies from these mothers (52.80 ± 5.39 cm) was higher than that of the babies of mothers with no abortion history (50.030 ± 2.506 cm). There was no significant relationship among other babies’ variables, such as weight, length, and the head circumference in either group of mothers. The median ± IQR values of trace elements for the exposed and unexposed mothers to SHS are presented in Table 4. Based on these results, the serum Hg levels (0.7 ± 0.5) was higher in mothers exposed to SHS aged older than 35 years, than those aged 35 years old or younger (0.4 ± 0.5; P = 0.04).

Regression analyses

Multivariate regression analyses were used to examine the factors that influenced the babies’ birth weight, length and head circumference (Table 5). These data were adjusted for other significant variables, such as age, education level and delivery type). Based on the coefficient and P values shown in Table 5, the mean serum Cu level for mothers exposed to SHS had a mildly negative effect on the babies’ weight (B = -0.002; P = 0.016 ). However, the mean Cr level had a significantly positive effect on the babies’ weight (B = 0.063; P = 0.044), height (B = 0.329; P = 0.001) and head circumference (B = 0.253; P = 0.005). In the same mothers, the exposure to Cd (B = 1.548; P = 0.041) and Pb (B = 0.112; P = 0.033) correlated with increases in the babies’ length. Conversely, increases in the serum levels of Zn,

Hg and Ni correlated with decreases in the babies’ length (B = -0.002, P = 0.040; B = -1.864, P = 0.017; & B = 0.234, P = 0.002), respectively. Also, in mothers exposed to SHS, increases in the serum Ni correlated significantly with decreases in the babies’ head circumference (B= -0.140, P = 0.036). In mothers unexposed to SHS, most trace elements had no significant correlation with the babies’ weight, length and head circumference. Based on the results from multiple regression analyses as reflected in Table 6, exposure to SHS did not significantly impacted the serum levels of any trace elements.

Discussion

Numerous toxic and carcinogenic compounds in cigarette smoke enter the environment and are inhaled at home, workplace and other public areas. Exposure to cigarette smoke, both directly and indirectly, is detrimental to human health18. This study investigated the effects of SHS on pregnant women, an important and vulnerable group in the community. In general, our results demonstrated that passive smokers had higher serum concentrations of trace elements than those unexposed to SHS, although the differences between the two groups were insignificant, except for the effects on the newborns’ growth indices. The findings of the current study suggest significant associations of trace elements with various birth metrics among the newborn babies of mothers exposed to SHS. Our results regarding the effects of trace elements exposure on the newborns’ anthropometric features both agree with and differ from the existing literature in several aspects.

Earlier studies have shown that both active and passive smoking result in elevated serum blood levels of heavy metals in smokers compared to non-smokers19,20,21,22,23,24,25. Apostolou, et al.., have reported that higher number of smokers at home increases the Pb level in children’s blood26. It has already been shown that the mean Pb level in indoor air has been higher in homes where smoking occurs than in those where no smoking occurs (21.8 ng/m3 vs. 7.8 ng/m3)27. A study conducted in Turkey has shown that children whose parents smoked had significantly higher levels of Cd, Pb, Cr, Sb, Fe, and Al in their hair samples compared to children of nonsmoking parents28. It is no surprise that exposure to tobacco smoke is linked to high levels of trace elements in the hair samples. Different brands of tobaccos and cigarettes contain varying amounts of toxic trace elements, such as As, Cd, Cr, Ni, and Pb, all of which known to be carcinogenic to humans29,30,31.

The accumulative effects of trace elements in the body can be harmful to health over time. In the current study, most mothers reported their concurrent exposure to SHS. Thus, much attention should be paid to such metals, as Pb and Cd in the environmental air, especially because their half-life in humans are 10–12 years32. Exposure to other trace elements, such as As, Cd, and Ni even at low concentrations may lead to carcinogenic outcomes. Therefore, much attention should be paid to the trans-placental carcinogenesis induced by exposure to the trace toxic elements33.

Our findings demonstrated that the serum levels of Cr and Ni in mothers exposed to SHS were significantly higher than those in the unexposed mothers even though the findings from the regression analyses on these metals were not necessarily alarming. The serum levels of Cr and Ni found in this study may suggest contaminations since they exceeded the expected serum values in the general population. The findings emphasize the need for further research on the subject. Consistent with our findings, Moradnia, et al., measured the urinary Cr and Ni levels in pregnant Iranian women, and suggested their association with lifestyle. Mean serum levels of Cr and Ni were significantly linked to passive exposure to cigarette smoke during pregnancy. This association may be due to various factors, including cooking utensils made of copper, aluminum, Teflon, and steel, as well as the use of cosmetics34.

The general public is often exposed to Ni ions through breathing air, or consuming foods, and water. The adverse health effects of exposure to Ni include pulmonary fibrosis, contact dermatitis, and increased risk of cancers35. Nickel can easily cross the placental barrier and enter fetal blood and the amniotic fluid35. Developing organisms are particularly sensitive to a variety of toxins and carcinogens due to their rapid cell proliferation33. A former study conducted in 1992 has reported that Ni(II) is a potent trans-placental initiator of epithelial tumors in fetal rat kidneys and pituitary gland. Thus, it can be a major trans-placental carcinogen36. Other studies have suggested that Ni exposure may pose a significant risk of congenital malformations and prematurity35,37. A more recent study conducted in 2020 investigated maternal Ni exposure versus gestational length in a large birth cohort consisting of 7291 pregnant women in China32. The findings suggested that high level of Ni in the maternal urine was significantly associated with mildly reduced gestational age and increased risks of preterm delivery.

Chromium is a naturally occurring heavy metal found in the air, soil, water, and foods. Environmental Cr predominantly consists of two steady states of oxidation, i.e., trivalent (III) and hexavalent Cr (VI)38. Further, a higher risk of preterm birth is associated with increased maternal urinary level of chromium38. Chromium III is an essential trace element that originates from normal carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. This is the form that is available in most foods and nutritional supplements with very low risk of toxicity39. However, the nutritional necessity of chromium has recently been argued40. The hexavalent Cr is a heavy metal ion and is much more toxic than its trivalent counterpart. The International Agency for Research on Cancer has classified chromium (VI) as a carcinogen to humans through inhalation41. Both chromium versions (III &VI) can lead to adverse effects on fertility, reproduction, and the developmental processes of embryo in animals and humans42,43,44.

Our study results showed that serum Cu levels are inversely related to birth weight in infants of exposed mothers. This is contrary to some studies suggesting that essential metals, such as Cu, are crucial in fetus development the deficiency of which is linked to lower birth weights45. Also, our study is in contrast with the findings of Oztan, et al.. who reported a positive correlation between Cu levels and birth weight46. However, other studies support our results, indicating that high Cu levels may adversely impact the normal fetal growth47. Özdemir, et al.. have suggested that increased Cu levels in both maternal and the cord blood may be associated with restricted fetal growth because of its adverse effects on the activity of the SOD1 enzyme48. On the other hand, Fahmey, et al.. did not find a significant relationship between serum Cu levels and body weight in the preterm neonates49. The discrepancy may suggest that the effect of Cu on fetal growth could vary by other contextual factors. There have been associations between high copper levels and the dysregulation of glucose metabolism during pregnancy. This can have consequences for fetal growth since glucose is a major energy source in fetus during development50.

We found positive associations between Cr concentrations and birth weight, length, and head circumference in the mothers and SHS. A positive relationship between Cr and the above-mentioned birth parameters has been less often reported in the literature, so the potential toxic effect of high Cr levels remains a concern. A number of investigations have indicated that an increase in the levels of Cr in maternal urine samples at delivery and during pregnancy may result in a possible decrease in birth size and weight of the newborn51,52. However, these findings were not supported by other studies53,54. Our observations of reduced head circumference with a higher Ni level is supported by previous literature that linked heavy metal exposure to impaired fetal growth, particularly head circumference and birth weight55. In contrast, another study has reported that nickel concentration in the maternal urine did not affect the baby’s birth weight56.

Nickel is capable of crossing placental barrier thus inducing toxicity on embryonic tissues, resulting in reduced inner cell mass and trophoblast cell numbers57. The harmful effects of mercury on the birth length are consistent with studies that reported mercury may have adverse impacts on fetal growth through epigenetic modifications58. All of these findings suggest that the impact of trace elements on fetal development is complex and is likely to be influenced by a number of factors, such as maternal dietary intake and environmental variables. In addition, these findings underscore the importance of further research into the mechanisms whereby trace metals impact fetal development. From a practical perspective, they emphasize the monitoring and management of maternal exposure to trace toxic elements during pregnancy for optimal birth outcomes.

Limitations of the study

Despite the useful findings, this study had several limitations. Primarily, using a larger sample could add more generalizability to the findings and provide statistical power for unraveling linkage between SHS and trace elements in pregnant women. Although some confounding variables were controlled in this study, others, such as dietary patterns, socioeconomic status, lifestyle habits, and the subjects’ comorbidities might have influenced the trace element levels and the developmental indices of the babies. Also, we did not incorporate specific assessments or controls for sources such as water, food, and other environmental exposures in the current study, which might have affected the interpretation of our finding.

Conclusions

Our findings provide evidence for possible developmental hazards toward the neonates in pregnant women due to passive exposure to SHS. Our findings demonstrated that SHS is associated with significant increases in the serum levels of Cr and Ni in pregnant women. However, the regression analysis results were not significant for the trace metal levels that could have been influenced by exposure to passive smoking.

The current study revealed complicated patterns of associations between the serum levels of trace elements and newborn growth indices. Among the mothers exposed to SHS, higher levels of Cu were negatively associated with their babies’ birth weight. However, high Cr levels were positively linked to the birth weight, length, and head circumference. The elevated level of serum Ni was associated with reduced head circumference, and Hg affected newborn length negatively. Fewer associations were observed in the babies born to the non-exposed mothers. The results suggest the existence of complex interactions between SHS exposure, trace metal bioaccumulation, and fetal development.

This study has shown the dual effect of SHS exposure, where it may alter the serum levels of certain elements in pregnant women and contribute to growth abnormalities in newborns through yet unknown mechanism. Our findings emphasize the urgent need for preventive and educational programs to diminish SHS exposure of mothers during pregnancy, thus protecting the maternal and fetal health. Future studies should be conducted to examine the long-term effects of exposure to trace elements versus the maternal and the child health. Such research help elucidate the associations among factors that may affect pregnant women as they live in environments contaminated with cigarette smoke.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ritchie, H. Jan., Max Roser. Smoking. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. (2022). Retrieved from: https://ourworldindata.org/smoking [Online Resource]. Accessed.

James, J. M., George, G., Cherian, M. R. & Rasheed, N. Thirdhand smoke composition and consequences: A narrative review. Public. Health Toxicol. 2, 1–6 (2022).

Reitsma, M. B. et al. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and attributable disease burden in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 397, 2337–2360 (2021).

Courtney, R., Wiley Online & Library please complete this citation. (2015).

Torres, S., Merino, C., Paton, B., Correig, X. & Ramírez, N. Biomarkers of exposure to secondhand and thirdhand tobacco smoke: recent advances and future perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15, 2693 (2018).

Walton, K., Gentzke, A. S., Murphy-Hoefer, R., Kenemer, B. & Neff, L. J. Peer reviewed: exposure to secondhand smoke in homes and vehicles among US youths, united States, 2011–2019. Prev. Chronic Dis. 17 (2020).

Talhout, R. et al. Hazardous compounds in tobacco smoke. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 8, 613–628 (2011).

Rodgman, A. & Perfetti, T. A. The chemical components of tobacco and tobacco smoke (CRC, 2008).

Smoke, T. & Smoking, I. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. IARC Lyon. 1, 1–1452 (2004).

Ariyaee, M. et al. Comparison of metal concentrations in the organs of two fish species from the Zabol Chahnimeh reservoirs, Iran. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 94, 715–721 (2015).

Neisi, A. et al. Consumption of foods contaminated with heavy metals and their association with cardiovascular disease (CVD) using GAM software (cohort study). Heliyon 10 (2024).

Nozadi, F. et al. Association between trace element concentrations in cancerous and non-cancerous tissues with the risk of Gastrointestinal cancers in Eastern Iran. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 28, 62530–62540 (2021).

Hussain, M. & Mumtaz, S. E-waste: impacts, issues and management strategies. Rev. Environ. Health 29, 53–58 (2014).

Tolunay, H. E. et al. Heavy metal and trace element concentrations in blood and follicular fluid affect ART outcome. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 198 , 73–77 (2016).

Negahban, T. Passive smoking during pregnancy and obstetric outcomes in pregnant women referring to Rafsanjan Nicknafs hospital. Journal of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences. 9, 281–292 (2010).

Baheiraei, A., Shamsi, A., Kazem Nejad, A., Milani, A., Keshavarz, S. A. & M. & Assessment of weight gaining in infants exposed to environmental tobacco smoke. J. Adv. Med. Biomed. Res. 21, 95–106 (2013).

Rezaei, M. et al. A case control study on the relationship between urinary trace element levels and autism spectrum disorder among Iranian children. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29 (38), 57287–57295 (2022).

Kashani, H. et al. Subnational exposure to secondhand smoke in Iran from 1990 to 2013: a systematic review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 2608–2625 (2021).

Meltzer, H. et al. The impact of iron status and smoking on blood divalent metal concentrations in Norwegian women in the HUNT2 study. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 38, 165–173 (2016).

Beshgetoor, D. & Hambidge, M. Clinical conditions altering copper metabolism in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 67, 1017S–1021S (1998).

Shaper, A. et al. Effects of alcohol and smoking on blood lead in middle-aged British men. Br. Med. J. (Clin Res. Ed). 284, 299–302 (1982).

Mannino, D. M., Homa, D. M., Matte, T. & Hernandez-Avila, M. Active and passive smoking and blood lead levels in US adults: data from the third National health and nutrition examination survey. Nicotine Tob. Res. 7, 557–564 (2005).

Li, L. et al. Secondhand smoke is associated with heavy metal concentrations in children. Eur. J. Pediatrics. 177, 257–264 (2018).

Mansouri, B., Azadi, N. A., Sharafi, K. & Nakhaee, S. The effects of active and passive smoking on selected trace element levels in human milk. Sci. Rep. 13, 20756 (2023).

Rahmani, R. et al. Association of environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) with lead and cadmium concentrations in biological samples of children and women: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Environ. Health 39, 13–25 (2024).

Apostolou, A. et al. Secondhand tobacco smoke: a source of lead exposure in US children and adolescents. Am. J. Public Health. 102, 714–722 (2012).

Bonanno, L., Freeman, G., Greenberg, N., Lioy, P. & M. & Multivariate analysis on levels of selected metals, particulate matter, VOC, and household characteristics and activities from the Midwestern States NHEXAS. Appl. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 16, 859–874 (2001).

Serdar, M. A. et al. The correlation between smoking status of family members and concentrations of toxic trace elements in the hair of children. Biological trace element research148, 11–17 (2012).

O’Connor, R. J. et al. Toxic metal and nicotine content of cigarettes sold in China, 2009 and 2012. Tobacco control. 24, iv55-iv59 (2015).

Yaprak, E. et al. High levels of heavy metal accumulation in dental calculus of smokers: a pilot inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry study. J. Periodontal Res. 52 , 83–88 (2017).

Zeng, W. A. et al. Effect of calcium carbonate on cadmium and nutrients uptake in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) planted on contaminated soil. J. Environ. Biol. 37 , 163 (2016).

ElMohr, M., Faris, M., Bakry, S., Hozyen, H. & Elshaer, F. Effect of passive smoking on heavy metals concentration in blood and follicular fluid of patients on going ICSI. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 13, 2035–2040 (2020).

Huai, G. et al. Maternal and fetal exposure to four carcinogenic environmental metals. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 23, 458–465 (2010).

Moradnia, M., Attar, H. M., Heidari, Z., Mohammadi, F. & Kelishadi, R. Prenatal exposure To chromium (Cr) and nickel (Ni) in a sample of Iranian pregnant women: urinary levels and associated socio-demographic and lifestyle factors. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28 , 63412–63421 (2021).

Chen, X. et al. Maternal exposure to nickel in relation to preterm delivery. Chemosphere 193 , 1157–1163 (2018).

Diwan, B. A., Kasprzak, K. S. & Rice, J. M. Transplacental carcinogenic effects of nickel (II) acetate in the renal cortex, renal pelvis and adenohypophysis in F3447/NCr rats. Carcinogenesis. 13 , 1351–1357 (1992).

Quansah, R. & Jaakkola, J. J. Paternal and maternal exposure to welding fumes and metal dusts or fumes and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health. 82, 529–537 (2009).

Pan, X. et al. Prenatal chromium exposure and risk of preterm birth: a cohort study in Hubei, China. Sci. Rep. 7, 3048 (2017).

Mertz, W. Chromium in human nutrition: a review. J. Nutr. 123, 626–633 (1993).

Eastmond, D. A., MacGregor, J. T. & Slesinski, R. S. Trivalent chromium: assessing the genotoxic risk of an essential trace element and widely used human and animal nutritional supplement. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 38, 173–190 (2008).

IARC. Chromium, nickel and welding. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Int. Agency Res. Cancer Lyon. 49, 49–256 (1990).

Marouani, N. et al. Embryotoxicity and fetotoxicity following intraperitoneal administrations of hexavalent chromium to pregnant rats. Zygote 19, 229–235 (2011).

Sivakumar, K. K. et al. Prenatal exposure to chromium induces early reproductive senescence by increasing germ cell apoptosis and advancing germ cell cyst breakdown in the F1 offspring. Dev. Biol. 388, 22–34 (2014).

Elbetieha, A. & Al-Hamood, M. H. Long-term exposure of male and female mice to trivalent and hexavalent chromium compounds: effect on fertility. Toxicology 116, 39–47 (1997).

Singh, L., Anand, M., Agarwal, P. & Taneja, A. Correlation of low birth weight of neonates to placental levels of zinc, copper, iron, lipid peroxidation and glutathione. Toxicol. Int. (Formerly Indian J. Toxicology). 24, 220–124 (2017).

Oztan, O. et al. Investigation of the relationship between placenta trace element levels and methylated arginines. J. Health Sci. Med. 4, 746–751 (2021).

Bochkova, L., Kadymova, I. & Kiselev, A. Copper concentration in the blood serum of low birth weight newborns. Biomedical Pharmacol. J. 11, 1807–1810 (2018).

Ozdemir, U. et al. Correlation between birth weight, leptin, zinc and copper levels in maternal and cord blood. J. Physiol. Biochem. 63, 121–128 (2007).

Fahmey, S. S. et al. Association of serum zinc and copper with clinical parameters in preterm infants. Minia J. Med. Res. 31, 50–55 (2020).

Zheng, Y. et al. A prospective study of early pregnancy essential metal (loid) s and glucose levels late in the second trimester. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 104 , 4295–4303 (2019).

Xia, W. et al. A case-control study of maternal exposure to chromium and infant low birth weight in China. Chemosphere 144, 1484–1489 (2016).

Peng, Y. et al. Exposure to chromium during pregnancy and longitudinally assessed fetal growth: findings from a prospective cohort. Environ. Int. 121, 375–382 (2018).

Guo, Y. et al. Monitoring of lead, cadmium, chromium and nickel in placenta from an e-waste recycling town in China. Sci. Total Environ. 408, 3113–3117 (2010).

Cabrera-Rodríguez, R. et al. Occurrence of 44 elements in human cord blood and their association with growth indicators in newborns. Environ. Int. 116, 43–51 (2018).

Pedersen, M. et al. Elemental constituents of particulate matter and newborn’s size in eight European cohorts. Environ. Health Perspect. 124, 141–150 (2016).

Odland, J. Ø. et al. Urinary nickel concentrations and selected pregnancy outcomes in delivering women and their newborns among Arctic populations of Norway and Russia. J. Environ. Monit. 1, 153–161 (1999).

Zhang, N. et al. Metal nickel exposure increase the risk of congenital heart defects occurrence in offspring: A case-control study in China. Medicine 98, e15352 (2019).

Cardenas, A. et al. Differential DNA methylation in umbilical cord blood of infants exposed to mercury and arsenic in utero. Epigenetics 10, 508–515 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the reviewers from Medical Editors & Review Consultants International of Virginia, USA, for editing and structuring the text of the manuscript based on native English prior to submission to this journal. The authors would like to acknowledge the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences as well as the Clinical Research Development Center, Imam Reza Hospital for their assistance. We are also very grateful to all of the mothers who participated in this project.

Funding

This study was conducted with a financial support received from the Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (Grant number: 4020860).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KS, SN, BM, and AH generated the idea and design of the study. SN, BM, MA, and KT searched the literature in databases, and wrote parts of the manuscript. ZM participated in statistical analyses and edited the result part. KS, SN, BM, ZM, AH, MA, NEH, and KT reviewed the manuscript. KS, SN, BM, MA, NEH, and KT wrote the discussion section, and with KS and BM supervised all parts of the revision part of the manuscript. BM served as the corresponding author.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study’s protocols were reviewed and approved by Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences’ Ethics Committee (Ethics code: IR.KUMS.REC.1402.510).

Also, each participating woman reviewed the study protocol and signed a consent form prior to being enrolled in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sharafi, K., Nakhaee, S., Hassan, N.E. et al. Relationships of the serum levels of toxic trace elements in pregnant women versus exposure to second-hand smoke. Sci Rep 15, 7180 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91795-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91795-2