Abstract

This multi-center retrospective study aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of first-line immunotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients with brain metastases (BM). The study included 138 patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), either alone or in combination with brain radiotherapy (BRT), from 2020 to October 2023. Intracranial overall response rate (iORR), overall response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS), intracranial progression-free survival (iPFS), overall survival (OS) and treatment-related toxicities were evaluated. Although patients receiving ICIs plus BRT showed a trend toward longer OS compared with ICI alone, the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.201). Among 82 patients with available data, the iORR was 49.1% (35–63) in the ICIs alone group, and 75.9% (56–90) in the ICIs + BRT group. Notably, in patients requiring corticosteroids or mannitol, combination therapy was associated with a better prognosis (P = 0.05). We found that the iORR of patients treated with ICIs + BRT was improved and did not increase the incidence of serious adverse events (SAEs). Besides, the combination of ICIs and BRT improved the survival rate of subgroups of patients using corticosteroids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Approximately 20% of cancer patients are ultimately projected to develop brain metastases (BM)1, with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) constituting nearly half of these cases1. At the time of diagnosis, 25–30% of patients with advanced NSCLC present with BM, with this proportion escalating to 50% as the disease progresses1,2,3. Specific molecular subtypes of primary pulmonary neoplasms, such as EGFR mutations or ALK gene rearrangements, enables the use of targeted inhibitors4, which demonstrate improved effectiveness due to their superior permeability and activity in the brain5. For NSCLC patients lacking targetable genetic alterations, the current first-line systemic therapy involves immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) alone or combined with chemotherapy (CT)6,7.

Multiple clinical trials have paved the way for the approval of ICI monotherapy or combination regimens for metastatic NSCLC8,9,10. Previous studies have assessed the safety and efficacy of systemic therapies in patients with asymptomatic BM, whether treated or untreated, within the context of metastatic NSCLC11,12,13. The safety profiles of ICI monotherapy and ICI combinations in patients with BM have been documented14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. The Atezo-Brain study demonstrated the safety and efficacy of ICI combined with CT in the BM subgroup14. Likewise, Checkmate-227 evaluated the safety and efficacy of nivolumab plus ipilimumab and CT19. Nonetheless, the response rate of ICIs ranges from approximately 20% to 40%.

Considerable evidence supports the combination of radiotherapy and ICIs to improve the efficacy of treatment. Radiotherapy facilitates tumor antigen release and fosters T cell-mediated immune responses, effectively transforming irradiated tumors into in situ vaccines23,24. Furthermore, owing to the radio-responsiveness of endothelial cells and surrounding oligodendrocytes, radiotherapy can augment the permeability of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), thereby facilitating ICI penetration25. Radiotherapy also modulates the immune-suppressive tumor stromal microenvironment, thereby augmenting the effects of immunotherapy26. Simultaneously, ICIs possess the potential to amplify the radiation-induced abscopal effect, counteracting the immunosuppressive effects of radiotherapy27. Emerging preclinical and clinical evidence points to a synergistic effect between radiotherapy and ICIs in improving disease control and survival28,29,30,31,32. Retrospective studies by Yu et al. and Takehiro et al. have demonstrated that combining ICI with brain radiotherapy (BRT), either concurrently or sequentially, serves as a predictive factor for improved intracranial local progression-free survival (PFS), intracranial distant PFS, and overall survival (OS)33,34. However, both studies included patients who had progressed after developing resistance.

As the utilization of ICIs in NSCLC continues to expand, evaluating the safety and efficacy of combining ICIs with radiotherapy remains of paramount importance. However, limited data exist regarding the combination of BRT and ICIs in NSCLC patients with BM. Therefore, our study specifically included NSCLC patients with an initial diagnosis of BMs to exclude confounding factors related to disease progression following treatment and aims to assess the safety and effectiveness of first-line ICIs in NSCLC patients with BM, providing real-world insights into diagnosis and treatment strategies.

Result

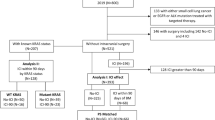

Table 1delineates the baseline characteristics of the 138 patients enrolled in this study. Baseline clinical data reveal median age of 61.6 and 61.1 years for patients in the respective cohorts, with ranges of 54.2–69.0 and 52.4–69.8 years. The majority of patients were male (n = 121, 87.7%). Histopathologically, 87 patients were diagnosed with adenocarcinomas, 41 with squamous cell carcinomas, 2 with adenosquamous carcinomas, 5 with large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas, and 3 with NSCLC- not otherwise specified (NOS). None of the patients harbored targetable mutations in EGFR, ALK, or ROS1. In both cohorts, 52 patients exhibited PD-L1 expression levels exceeding 1% (37.7%), 132 had Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status scores of 0 to 1 (95.7%), 107 had multiple BMs (77.5%), 133 received PD-1 ICIs (96.4%), and 133 underwent combination CT (96.4%). The diameter of brain lesions varied from 4 to 60 mm. Sixty patients presented with symptomatic BMs. 99 patients (71.7%) did not receive BRT, whereas 39 (28.3%) received ICIs combined with radiotherapy, including stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) and whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT). 49 patients (44.4%) in the ICIs group and 26 patients (66.7%) in the ICIs plus BRT group received corticosteroid or mannitol treatment. Corticosteroid types included dexamethasone, prednisone, and methylprednisolone sodium succinate, administered over 2 to 4 days. Both peak doses (the highest daily dose) and cumulative doses (the total of all daily doses) were calculated as prednisolone equivalents. Peak doses ranged from 0.5 to 2 mg/kg, and the maximum cumulative dose reached 1310 mg. Building upon recent findings indicating that the neutrophil-to-eosinophil ratio (NER) and other hematological parameters hold significant predictive value in ICIs for NSCLC, we collected and compared these indicators35. As presented in Table 1, no meaningful differences were observed in the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), or lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR) between patients receiving ICIs in combination with BRT and those treated with ICI monotherapy. The Kaplan–Meier (KM) curve for OS is depicted in Fig. 1. Although some evidence suggests that patients receiving ICIs plus BRT exhibited improved OS compared to those treated with ICIs alone, the difference between the two groups was not significant (HR = 0.652, 95%CI: 0.339–1.258, P = 0.201).

Table 2 summarizes the intracranial objective response rate (iORR) for the 82 evaluable patients, with an overall iORR of 58.5% (47–69), comprising 49.1% (35–63) in the ICIs group, and 75.9% (56–90) in the ICIs plus BRT group. Six patients (6.1%) in the ICIs group experience severe adverse events (SAEs), including myelosuppression, elevated amylase, and myocarditis, with each event occurring in a single patient. Analysis of brain lesions in patients from both cohorts demonstrated a significant improvement in iORR without a concomitant increase in SAEs.

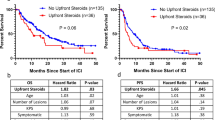

Table 3 presents the univariate and multivariate analyses for the entire cohort. Given the limited sample size and the substantial loss to follow-up in this retrospective study, only two independent prognostic factors were identified: the presence of extracranial metastases (HR 3.74, 95% CI 1.28–10.94) and combination CT (HR 0.06, 95% CI 0.01–0.34). A forest plot was generated to assess the benefits of ICIs + BRT (Fig. 2). For patients receiving corticosteroids or mannitol, OS with ICIs + BRT is superior to ICIs alone (HR = 0.16, 95%CI: 0.03–1.01, P = 0.05). However, among the remaining patients, there was no statistically significant difference in prognosis between the two treatment regimens.

Forest plot of overall survival in subgroups and overall population of patients with newly diagnosed brain metastases from non-small cell lung cancer receiving first-line immunotherapy. This forest plot reflects the comparison of the efficacy between ICI + BRT and ICI in each subgroup. An HR less than 1 indicates the superiority of ICI + BRT, while an HR greater than 1 indicates the superiority of ICI. Only in the subgroup of patients who received Hormones or mannitol, ICI + BRT was significantly superior to ICI.

Discussion

In the era of immunotherapy, this study presents compelling real-world evidence elucidating the potential benefits of integrating ICIs with brain radiotherapy in the management of NSCLC patients with BMs, accentuating its favorable impact on OS despite the absence of statistical significance in our findings.

Extensive prior studies have investigated the efficacy and safety of combining ICIs and radiotherapy. However, consensus on the efficacy of this combination therapy remains elusive. Certain studies contend that ICIs combined with brain radiotherapy significantly prolong patient prognosis. For instance, a retrospective study by Lee et al. demonstrated that gamma knife treatment administered 14 days post-treatment of NSCLC-BM patients with ICIs markedly improved OS36. The prospective study by Mehmet et al. in 2023 included 13 patients with BMs from NSCLC and assessed the safety and efficacy of nivolumab and ipilimumab alongside concurrent SRS, concluding that dual ICIs plus SRS exhibited a manageable safety profile37. Nevertheless, the study was constrained by a small cohort size and a single-arm design. A recent study by Lu et al. involving 113 patients evaluated the efficacy of ICIs plus CT versus ICIs plus CT combined with brain radiotherapy for the treatment of BMs in NSCLC patients. Their findings indicated that immune-based therapies, when paired with brain radiotherapy conferred statistically significant survival benefits38. Conversely, other studies align with our findings. The results of our survival data showed that patients treated with ICIs plus BRT had better OS compared to ICIs alone, with an HR of 0.652 (95%CI: 0.339–1.258). However, our results were not statistically significant due to the limited number of patients enrolled in the study, which is a limitation of our study. Watanabe et al. observed that BMs patients who had undergone prior radiotherapy exhibited prolonged PFS compared to those without radiotherapy, albeit without statistical significance39. A meta-analysis revealed that ICIs combined with radiotherapy did not improve PFS or OS compared to ICIs alone40. Teixeir et al.’s meta-analysis also failed to reveal a significant difference in the efficacy of ICIs in BMs patients treated with or without radiotherapy41. Similarly, a study by Hendriks et al. found that prior brain radiotherapy was not associated with PFS in univariate analysis (HR = 0.80, 95% CI: 0.60–1.08, p = 0.144), which corroborates our results42.

We posit that discrepancies between these studies may stem from the following factors: 1) variations in cohort sizes. Lee’s study included 77 patients, while Mehmet’s study featured only 13 patients. Lu’s study encompassed the largest cohort with 113 patients36,37,38. 2) Differences in treatment lines. In the studies conducted by Lee, Mehmet, and Hendriks, over half of the patients exhibited metachronous BMs, and ICIs were administered as later-line treatment, potentially amplifying the radiotherapy effect36,37,42. Lu’s study is more analogous to ours, as both included patients with synchronous BMs receiving first-line immunotherapy38. 3) Differences in radiotherapy regimens. In Lu’s study, 31% of patients received WBRT and 41% received WBRT plus Boost38. Given the potential for cognitive impairment, current guidelines advocate for SRS in patients with limited metastases, which accounts for the greater proportion of SRS-treated patients in our study. In summary, methodological heterogeneity significantly influences study outcomes. Our study primarily focuses on the efficacy and safety of immunotherapy, and its combination with brain radiotherapy, in patients with synchronous NSCLC BMs and negative driver gene status, with SRS serving as the predominant radiotherapy modality. Unlike metachronous BMs, the microenvironment of synchronous BMs more analogous to the primary lesion, potentially better reflecting the synergistic effects of first-line immunotherapy and radiotherapy. Although our results showed no significant survival benefit with the addition of brain radiotherapy, analysis of the lesions in both cohorts revealed that the iORR of patients receiving ICIs plus brain radiotherapy was significantly enhanced, without a concomitant rise in severe adverse events. Furthermore, our treatment approach aligns with existing guidelines, thus we believe our study bridges a critical gap in the literature and offers valuable insights for clinical practice.

Moreover, our multivariable cox regression analysis identifies that the use of combination CT is an important independent prognostic factor for survival. Multiple phase III clinical trials underscore that ICIs in combination with CT are beneficial for all patients with advanced lung cancer, irrespective of PD-L1 expression. The results of KEYNOTE-189 revealed a mPFS of 8.8 months for combination therapy43. Camrelizumab plus CT also achieved a mPFS of 11.3 months in NSCLC patients with BMs44. Comparable efficacy was observed with the combination of CT, sintilimab and atezolizumab45,46. Our results further corroborate that ICI + CT improves the survival of patients with BMs from NSCLC. One plausible reason could be that CT mitigates the occurrence of hyper-progression associated with ICIs in lung cancer patients without significantly exacerbating AEs47.

In addition, baseline patient characteristic analysis revealed that although other baseline characteristics (including symptomatic BMs) did not differ significantly between the two cohorts, a greater proportion of patients in the ICIs plus BRT group had their cranial pressure reduced by using mannitol, corticosteroids, and other therapies, and this difference was statistically significant. Our subgroup analysis further demonstrated that combined ICIs plus BRT conferred a survival benefit in the corticosteroids -treated patients. This might imply that NSCLC patients with BMs receiving ICIs combined with radiotherapy tend to experience more severe intracranial hypertension compared to those receiving ICIs alone. According to the 2021 European Association of Neuro-Oncology (EANO)–European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines , administering anti-edema treatment with corticosteroids in patients presenting with neurological deficits may not only alleviate mass effects, such as nausea, vomiting, and fatigue, but also improve survival48. Furthermore, analysis of dynamic MRI from 30 patients with BMs by Teng et al. revealed an increase in permeability in tumors with initially low permeability following brain radiotherapy49. This increase in permeability may exacerbate cerebral edema post-radiotherapy, which Harat et al. reported could persist for up to six months after SRS or WBRT50. In addition to the possibility that brain radiotherapy itself may cause brain injury after radiotherapy, some previous clinical studies have shown that ICIs have the potential to increase the occurrence of radiation-induced brain injury51,52. However, some recent retrospective studies have shown that immunotherapy is not significantly associated with radiation-induced brain injury, and due to the lack of prospective studies and the heterogeneity of patients included, the conclusion needs further exploration53,54,55. Even so, our study found that immunotherapy was not significantly associated with radiation-induced brain injury, which may be linked to the use of anti-edema treatments such as steroids in our cohort. Consistent with the 2022 American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) guidelines, we posit ICIs alone for asymptomatic BMs, while combining ICIs with brain radiotherapy remains advantageous for symptomatic patients, without increasing the likelihood of post-treatment adverse events, provided anti-edema treatment is employed when appropriate56.

We observed that numerous studies emphasize the significance of PD-L1 expression57,58. Chen et al.’s meta-analysis found higher iORR and iDCR in patients with high PD-L1 expression compared to those with no or low PD-L1 expression treated with pembrolizumab59. However, our data did not yield similar results. Our team discovered through RNA sequencing that BMs exhibit an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME)60. It has also been demonstrated that BMs have different PD-L1 expression levels compared to primary lung tumors61. Since our study excluded patients with prior systemic therapy and focused exclusively on BMs, eliminating the confounding effect of treatment-induced resistance, we propose that the specific immunosuppressive TME of BMs, which results in divergent PD-L1 expression compared to primary lung lesions, rendered PD-L1 expression non-predictive of efficacy in our study. Additionally, as our retrospective study included patients treated with different ICIs, and the correlation between PD-L1 expression and the efficacy of various ICIs varies, this could also contribute to the findings59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66.

Our cox multivariate regression analysis also identified the presence of extracranial metastases as an independent prognostic factor, aligning with DS-GPA and Lung-molGPA systems67,68. Therefore, we believe that adequate local therapy should be employed to control extracranial metastatic lesions.

The principal limitation of our study lies in its retrospective design, which results in missing data and selection bias. Although data from three centers were included, we acknowledge that the patient sample size was limited. Future large-scale prospective trials are warranted to evaluate brain radiotherapy combined with ICIs in the treatment of NSCLC BMs. By focusing exclusively on synchronous BMs, our study mitigates confounding factors, providing significant contributions to existing knowledge. Until further prospective data are available, we believe our findings offer critical insights and actionable guidance for clinicians managing NSCLC patients with BMs.

Method

Patients

Clinical data from NSCLC patients with BMs treated with first-line ICIs at Xiangya Hospital, Xiangya Changde Hospital and Xiangya Boai Hospital between 2020 and October 2023 were retrospectively collected. The inclusion criteria comprised: 1) diagnosis of NSCLC with BMs at initial presentation; 2) presence of at least one quantifiable brain lesion corroborated by MRI at initial diagnosis; and 3) administration of first-line ICI. Patients were excluded if they: 1) had small cell lung cancer; 2) lacked measurable BMs detected at initial diagnosis; or 3) had undergone treatment with other antineoplastic agents prior to ICIs. Patients who underwent radiotherapy for BMs either preceding or subsequent ICIs were included.

General information was compiled, encompassing demographics (name, gender, age ), tobacco and alcohol consumption history, antecedent chronic illnesses, oncological history, ECOG-PS score, status of primary malignancy, and status of extracranial metastases. Clinicopathological attributes, driver gene mutations, PD-L1 tumor proportional score, and treatment regimen were recorded. Hematological parameters, including erythrocytes, platelets, neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophil counts, were collected pre- and post-ICIs administration.

Patients were stratified into two cohorts based on their receipt of BRT. Concurrent ICIs with BRT were defined as ICIs administered within two weeks before or after radiotherapy. Patients who received non-concurrent BRT and ICIs were defined as those receiving radiotherapy and ICIs more than 2 weeks apart. Radiotherapy was classified as any modality of BRT including WBRT and SRS.

To ensure the safeguarding of patient confidentiality and personal identity, and considering that the associated risks did not exceed minimal levels, the study adhered to an ethically approved alternative protocol.

Assessments

The primary endpoints were iORR and ORR. Control of intracranial and extracranial lesions was assessed by MRI and CT every 3 months. The efficacy of each assessment was categorized as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD), in accordance with the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1. Secondary endpoints included PFS, iPFS, OS and treatment-related toxicity. PFS was defined as the duration from initiation of ICIs to disease progression or mortality from any cause. iPFS was defined as the interval from initiation of ICIs to progression of intracranial lesions or death. OS was defined as the period from the initiation of ICIs until death from any cause or until the last documented follow-up. Treatment-related toxicities were assessed in accordance with the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.0.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis were conducted utilizing R software (4.2.3). Cox proportional hazards regression models were applied to assess factors independently associated with OS, PFS, and iPFS. The distribution of patients’ baseline characteristics was summarized using frequency analysis. Fisher’s exact test was utilized to evaluate the baseline characteristics of patients receiving various treatment strategies. The KM analysis was employed to estimate iPFS, PFS and OS , and the log-rank test was applied to compare survival differences between subgroups.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Access to the data will be considered following review of a detailed research proposal to ensure appropriate use and protection of patient information.

References

Achrol, A. S. et al. Brain metastases. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 5, 5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-018-0055-y (2019).

Cagney, D. N. et al. Incidence and prognosis of patients with brain metastases at diagnosis of systemic malignancy: A population-based study. Neuro. Oncol. 19, 1511–1521. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nox077 (2017).

Waqar, S. N. et al. Non-small-cell lung cancer with brain metastasis at presentation. Clin. Lung Cancer 19, e373–e379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cllc.2018.01.007 (2018).

Lamberti, G. et al. Beyond EGFR, ALK and ROS1: Current evidence and future perspectives on newly targetable oncogenic drivers in lung adenocarcinoma. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 156, 103119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2020.103119 (2020).

Venur, V. A. & Ahluwalia, M. S. Targeted therapy in brain metastases: Ready for primetime?. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 35, e123-130. https://doi.org/10.1200/edbk_100006 (2016).

Planchard, D. et al. Metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 29, iv192–iv237. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdy275 (2018).

Singh, N. et al. Therapy for stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer without driver alterations: ASCO living guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 3323–3343. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.22.00825 (2022).

Rizzo, A., Dall’Olio, F. G., Altimari, A., Giunchi, F. & Ardizzoni, A. Role of PD-L1 assessment in advanced NSCLC: Does it still matter?. Anticancer Drugs 32, 1084–1085. https://doi.org/10.1097/CAD.0000000000001118 (2021).

Sahin, T. K., Rizzo, A., Aksoy, S. & Guven, D. C. Prognostic significance of the royal marsden hospital (RMH) score in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16101835 (2024).

Rizzo, A. Identifying optimal first-line treatment for advanced non-small cell lung carcinoma with high PD-L1 expression: A matter of debate. Br. J. Cancer 127, 1381–1382. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-022-01929-w (2022).

Guven, D. C. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related hearing loss: A systematic review and analysis of individual patient data. Support Care Cancer 31, 624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-08083-w (2023).

Rizzo, A. et al. Peripheral neuropathy and headache in cancer patients treated with immunotherapy and immuno-oncology combinations: The MOUSEION-02 study. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 17, 1455–1466. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425255.2021.2029405 (2021).

Viscardi, G. et al. Comparative assessment of early mortality risk upon immune checkpoint inhibitors alone or in combination with other agents across solid malignancies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 177, 175–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2022.09.031 (2022).

Nadal, E. et al. Updated analysis from the ATEZO-BRAIN trial: Atezolizumab plus carboplatin and pemetrexed in patients with advanced nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer with untreated brain metastases. Journal of Clinical Oncology 40 (2022).

Gadgeel, S. M. et al. Atezolizumab in patients with advanced non -small cell lung cancer and history of asymptomatic, treated brain metastases: Exploratory analyses of the phase III OAK study. Lung Cancer 128, 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.12.017 (2019).

Mans, A. S. et al. Outcomes with pembrolizumab monotherapy in patients with programmed death-ligand 1-positive NSCLC With brain metastases: Pooled analysis of KEYNOTE-001, 010, 024, and 042. Jto Clin. Res. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtocrr.2021.100205 (2021).

Powell, S. F. et al. Outcomes with pembrolizumab plus platinum-based chemotherapy for patients with NSCLC and stable brain metastases: Pooled analysis of KEYNOTE-021,-189, and-407. J. Thorac. Oncol. 16, 1883–1892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2021.06.020 (2021).

Goldberg, S. B. et al. Pembrolizumab for management of patients with NSCLC and brain metastases: Long-term results and biomarker analysis from a non -randomised, open -label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 21, 655–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(20)30111-x (2020).

Reck, M. et al. Nivolumab (NIVO) plus ipilimumab (IPI) as first-line (1L) treatment (tx) for patients (pts) with advanced NSCLC (aNSCLC) and baseline (BL) brain metastases (mets): Intracranial and systemic outcomes from CheckMate 227 Part 1. Ann. Oncol. 32, S1430–S1431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2021.10.141 (2021).

Tawbi, H. A. et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in melanoma metastatic to the brain. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 722–730. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1805453 (2018).

Long, G. V. et al. Combination nivolumab and ipilimumab or nivolumab alone in melanoma brain metastases: A multicentre randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 19, 672–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(18)30139-6 (2018).

Rizzo, A. et al. Impact of proton pump inhibitors and histamine-2-receptor antagonists on non-small cell lung cancer immunotherapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14061404 (2022).

Garnett, C. T. et al. Sublethal irradiation of human tumor cells modulates phenotype resulting in enhanced killing by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 64, 7985–7994. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.Can-04-1525 (2004).

Wan, S. et al. Chemotherapeutics and radiation stimulate MHC class I expression through elevated interferon-beta signaling in breast cancer cells. Plos One https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0032542 (2012).

Tian, W., Chu, X., Tanzhu, G. & Zhou, R. Optimal timing and sequence of combining stereotactic radiosurgery with immune checkpoint inhibitors in treating brain metastases: Clinical evidence and mechanistic basis. J. Transl. Med. 21, 244. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-023-04089-4 (2023).

Menon, H. et al. Role of radiation therapy in modulation of the tumor stroma and microenvironment. Front. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.00193 (2019).

Ngwa, W. et al. Using immunotherapy to boost the abscopal effect. Nat. Rev. Cancer 18, 313–322. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc.2018.6 (2018).

Demaria, S. et al. Immune-mediated inhibition of metastases after treatment with local radiation and CTLA-4 blockade in a mouse model of breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 728–734 (2005).

Yoshimoto, Y. et al. Radiotherapy-induced anti-tumor immunity contributes to the therapeutic efficacy of irradiation and can be augmented by CTLA-4 blockade in a mouse model. Plos One https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0092572 (2014).

Kiess, A. P. et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for melanoma brain metastases in patients receiving ipilimumab: Safety profile and efficacy of combined treatment. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 92, 368–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.01.004 (2015).

Wu, C. T., Chen, W. C., Chang, Y. H., Lin, W. Y. & Chen, M. F. The role of PD-L1 in the radiation response and clinical outcome for bladder cancer. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep19740 (2016).

Kim, Y. H. Durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 989–990 (2019).

Yu, Y. et al. Improved survival outcome with not-delayed radiotherapy and immediate PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor for non-small-cell lung cancer patients with brain metastases. J. Neurooncol. 165, 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-023-04459-4 (2023).

Tozuka, T. et al. Immunotherapy with radiotherapy for brain metastases in patients with NSCLC: NEJ060. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 5, 100655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtocrr.2024.100655 (2024).

Sahin, T. K., Ayasun, R., Rizzo, A. & Guven, D. C. Prognostic value of neutrophil-to-eosinophil ratio (NER) in cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16213689 (2024).

Lee, M. H. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for non-small-cell lung cancer with brain metastasis : The role of gamma knife radiosurgery. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 64, 271–281. https://doi.org/10.3340/jkns.2020.0135 (2021).

Altan, M. et al. Nivolumab and ipilimumab with concurrent stereotactic radiosurgery for intracranial metastases from non-small cell lung cancer: analysis of the safety cohort for non-randomized, open-label, phase I/II trial. J. Immunother. Cancer https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2023-006871 (2023).

Lu, S. et al. Immunotherapy combined with cranial radiotherapy for driver-negative non-small-cell lung cancer brain metastases: A retrospective study. Future Oncol. https://doi.org/10.2217/fon-2023-1061 (2024).

Watanabe, H. et al. The effect of nivolumab treatment for central nervous system metastases in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.e20601 (2017).

Chu, X. et al. The long-term and short-term efficacy of immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer patients with brain metastases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 13, 875488. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.875488 (2022).

Teixeira Loiola de Alencar, V., Guedes Camandaroba, M. P., Pirolli, R., Fogassa, C. A. Z. & Cordeiro de Lima, V. C. Immunotherapy as single treatment for patients with NSCLC with brain metastases: A systematic review and meta-analysis-the META-L-BRAIN study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 16, 1379–1391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2021.04.014 (2021).

Hendriks, L. E. L. et al. Outcome of patients with non-small cell lung cancer and brain metastases treated with checkpoint inhibitors. J. Thorac. Oncol. 14, 1244–1254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2019.02.009 (2019).

Gandhi, L. et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 2078–2092. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1801005 (2018).

Zhou, C. et al. Camrelizumab plus carboplatin and pemetrexed versus chemotherapy alone in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (CameL): A randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 9, 305–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30365-9 (2021).

Yang, Y. et al. Efficacy and safety of sintilimab plus pemetrexed and platinum as first-line treatment for locally advanced or metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC: A randomized, double-blind, phase 3 study (Oncology pRogram by InnovENT anti-PD-1-11). J. Thorac. Oncol. 15, 1636–1646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2020.07.014 (2020).

Nishio, M. et al. Atezolizumab plus chemotherapy for first-line treatment of nonsquamous NSCLC: Results from the randomized phase 3 IMpower132 trial. J. Thorac. Oncol. 16, 653–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2020.11.025 (2021).

Matsuo, N. et al. Comparative incidence of immune-related adverse events and hyperprogressive disease in patients with non-small cell lung cancer receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors with and without chemotherapy. Invest. New Drugs 39, 1150–1158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10637-021-01069-7 (2021).

Roth, P. et al. Neurological and vascular complications of primary and secondary brain tumours: EANO-ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for prophylaxis, diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 32, 171–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2020.11.003 (2021).

Teng, F., Tsien, C. I., Lawrence, T. S. & Cao, Y. Blood-tumor barrier opening changes in brain metastases from pre to one-month post radiation therapy. Radiother. Oncol. 125, 89–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2017.08.006 (2017).

Harat, M., Lebioda, A., Lasota, J. & Makarewicz, R. Evaluation of brain edema formation defined by MRI after LINAC-based stereotactic radiosurgery. Radiol. Oncol. 51, 137–141. https://doi.org/10.1515/raon-2017-0018 (2017).

Diao, K. et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery and ipilimumab for patients with melanoma brain metastases: Clinical outcomes and toxicity. J. Neurooncol. 139, 421–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-018-2880-y (2018).

Colaco, R. J., Martin, P., Kluger, H. M., Yu, J. B. & Chiang, V. L. Does immunotherapy increase the rate of radiation necrosis after radiosurgical treatment of brain metastases?. J. Neurosurg. 125, 17–23. https://doi.org/10.3171/2015.6.JNS142763 (2016).

Botticella, A. & Dhermain, F. Combination of radiosurgery and immunotherapy in brain metastases: Balance between efficacy and toxicities. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 36, 587–591. https://doi.org/10.1097/WCO.0000000000001217 (2023).

Jablonska, P. A. et al. Toxicity and outcomes of melanoma brain metastases treated with stereotactic radiosurgery: The risk of subsequent symptomatic intralesional hemorrhage exceeds that of radiation necrosis. J. Neurooncol. 164, 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-023-04404-5 (2023).

Lehrer, E. J. et al. Radiation necrosis in renal cell carcinoma brain metastases treated with checkpoint inhibitors and radiosurgery: An international multicenter study. Cancer 128, 1429–1438. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.34087 (2022).

Vogelbaum, M. A. et al. Treatment for brain metastases: ASCO-SNO-ASTRO guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 492–516. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.21.02314 (2022).

Taube, J. M. et al. Association of PD-1, PD-1 ligands, and other features of the tumor immune microenvironment with response to anti-PD-1 therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 20, 5064–5074. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3271 (2014).

Gibney, G. T., Weiner, L. M. & Atkins, M. B. Predictive biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy. Lancet. Oncol. 17, e542–e551. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30406-5 (2016).

Chen, H. et al. Brain metastases and immune checkpoint inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 71, 3071–3085. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-022-03224-2 (2022).

Xiao, G. et al. Heterogeneity of tumor immune microenvironment of EGFR/ALK-positive tumors versus EGFR/ALK-negative tumors in resected brain metastases from lung adenocarcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2022-006243 (2023).

Wang, H. et al. The metastatic site does not influence PD-L1 expression in advanced non-small cell lung carcinoma. Lung Cancer 132, 36–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.04.009 (2019).

Borghaei, H. et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 1627–1639. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1507643 (2015).

Rittmeyer, A. et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 389, 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32517-X (2017).

Herbst, R. S. et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 387, 1540–1550. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01281-7 (2016).

Goldberg, S. B. et al. Pembrolizumab for patients with melanoma or non-small-cell lung cancer and untreated brain metastases: Early analysis of a non-randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 17, 976–983. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(16)30053-5 (2016).

Carbone, D. P. et al. First-line nivolumab in stage IV or recurrent non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 376, 2415–2426. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1613493 (2017).

Sperduto, P. W. et al. Estimating survival in patients with lung cancer and brain metastases: An update of the graded prognostic assessment for lung cancer using molecular markers (Lung-molGPA). JAMA Oncol. 3, 827–831. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3834 (2017).

Sperduto, P. W. et al. Diagnosis-specific prognostic factors, indexes, and treatment outcomes for patients with newly diagnosed brain metastases: A multi-institutional analysis of 4,259 patients. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 77, 655–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.08.025 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us during the writing of this manuscript.Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Multidisciplinary Cooperative Diagnosis and Treatment Capacity (lung cancer z027002), Clinical Research Special Fund of Wu Jieping Medical Foundation (32067502021225), Clinical Research Special Fund of Wu Jieping Medical Foundation (320.6750.2023–5-109), National Clinical Research Center for Geriatric Disorders (No. 2022LNJJ10), Health Research Project of Hunan Provincial Health Commission (grant number: W20242005), Advanced Lung Cancer Targeted Therapy Research Foundation of China (CTONG-YC20210303), and Chen Xiao-Ping Foundation for the Development of Science and Technology of Hubei Province (CXPJJH121005-01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, R.L. and Z.W.; methodology, R.L. and Z.W.; software, R.L. and Z.W.; validation, X.C. and R.Z., formal analysis, R.L. and Z.W.; investigation, R.L. and Z.W.; resources, R.L. and Z.W.; data curation, R.L. and Z.W.; writing—original draft preparation, R.L., Z.W. and W.T.; writing—review and editing, R.L., Z.W., W.T. and W.S.; visualization, R.L. and Z.W., X.C.; supervision, X.C. and R.Z.; project administration, X.C. and R.Z.; funding acquisition, R.Z.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (202406122). In accordance with the Ethical Review Methodology for Biomedical Research Involving Humans (2016 Edition) established by the Chinese authorities, the Ethics Committee of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University granted approval for the waiver of patient consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, R., Wang, Z., Tian, W. et al. A retrospective study of radiotherapy combined with immunotherapy for patients with baseline brain metastases from non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Rep 15, 7036 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91863-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91863-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Synergy of radiotherapy, focused ultrasound, and immunotherapy in the treatment of brain metastases

Journal of Neuro-Oncology (2026)

-

Local cranial radiation combined with third-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors improve leptomeningeal metastasis disease-free survival in patients with EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer and brain metastasis

Journal of Neuro-Oncology (2025)

-

The safety and efficacy of encorafenib plus binimetinib for brain metastases: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Discover Oncology (2025)

-

Tailored radiotherapy for brain metastases improves precision and outcomes

Discover Oncology (2025)