Abstract

The biological processes involved in diseases like human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and tuberculosis (TB) require extensive research, particularly when both diseases occur together. This piece of research delves to explore a new fractional-order mathematical model that examines the co-dynamics of HIV and TB, taking into account the treatment effects. Although no definitive vaccine or cure for HIV exists, antiretroviral therapy (ART) can slow disease spread and prevent subsequent complications. The basic properties of the fractional model in the Caputo sense, including existence, uniqueness, positivity, and boundedness, are proved using crucial mathematical tools. The disease-free and endemic equilibria are determined for the co-infection model, along with the basic reproduction numbers \(R_T\) for TB and \(R_H\) for HIV, using the next-generation matrix technique. A comprehensive analysis is conducted to determine the local and global stability of the disease-free equilibrium point by applying the Routh–Hurwitz criteria and constructing a Lyapunov function, respectively. The stability of the disease-free state is also verified graphically by considering different initial conditions and observing the convergence of the curves to the disease-free equilibrium point. Furthermore, the model is examined under different scenarios by varying the reproduction numbers, specifically when \(R_T < 1\) and \(R_H > 1\), and when \(R_T > 1\) and \(R_H < 1\). Using actual data from the USA from 1999 to 2022, crucial parameters are estimated. The final fitting of the model with real data demonstrates how effectively the model framework aligns with the data. Finally, computational simulations are performed for different cases to illustrate the behavior of the model solutions by varying the fractional order derivative, as well as examining the solution’s behavior with respect to the stability points.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a respiratory infection triggered by the microbe Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It is an airborne-transmitted disease that mainly targets the lungs but can also affect other organs like the kidneys, spine, and brain1. TB is a widely acknowledged disease that plays a major role in global mortality and morbidity. Every year, TB continues to affect millions of people. According to latest report of WHO approximately 10.6 million new tuberculosis cases were documented worldwide in 2022, resulting in about 1.6 million deaths. It is projected that 10.6 million people globally will have contracted TB by 2021, and that 1.6 million of those cases will result in fatalities. While, in 2020, about 10 million people were affected by TB, with the number of deaths rising to approximately 1.5 million, largely due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic2. The treatment for TB typically involves a 6-month regimen of antibiotics, including isoniazid, pyrazinamide, rifampin, and ethambutol, which play a key role in bolstering the immune system. Integrating antiretroviral therapy (ART) is essential for improving patient survival, with recommendations suggesting its initiation within 8 weeks of starting TB therapy, or within 2 weeks for individuals with CD4 levels3 below 50 cells per \(\hbox {mm}^3\).

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) damages the defense system by targeting critical immunity cells, which results in Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS). The human body is more prone to potentially fatal opportunistic infections and tumors when living with AIDS. Rectal secretions, breast milk, semen, and vaginal fluids are among the bodily fluids from an infected person that can be shared4. Other ways of transmission include sharing needles/razors, engaging in unprotected sex, and breastfeeding or childbirth. HIV does not spread through casual contact such as handshakes or hugging. HIV remains a critical global concern, marked by a substantial mortality rate. According to the most recent UNAIDS Global HIV Statistics, approximately 38.4 million people worldwide are living with HIV. Sub-Saharan Africa continues to be the most impacted region by the epidemic, with the greatest prevalence rates5. HIV treatment primarily relies on antiretroviral therapy (ART), a lifelong approach that combines multiple medications to control the virus, halt its progression to AIDS, and enhance overall well-being. ART works by lowering the viral load to undetectable levels, thereby safeguarding the immune system and maintaining CD4+ T cell functionality. Consistent adherence to the regimen is essential to avoid drug resistance and sustain viral control. Routine blood tests are conducted to monitor the treatment’s effectiveness. While ART does not eradicate the virus, it significantly extends an individual’s life expectancy, promotes a healthy life, and prevents further transmission of HIV.

Mathematical modeling within applied mathematics is devoted to formulating equations that help represent and understand different phenomena, employing diverse tools to handle complex equations and generate accurate forecasts6. By linking theoretical concepts with real-world phenomena, mathematical modeling plays a vital role in enhancing our ability to analyze, predict, and solve a wide range of problems, particularly in healthcare, where it aids in understanding disease transmission and developing strategies to improve public health7. Several academics have reported on mathematical modeling of HIV, TB, and HIV/TB co-infections in recent years. However, most of these models do not incorporate the treatment of the diseases simultaneously. Observational studies indicate that raising CD4 counts in individuals who are taking ART and anti-TB treatment underscores the need for prompt and effective management of co-infections to enhance patient outcomes. Tuberculosis can be treated and cured, typically requiring a minimum of six months of treatment for a complete recovery. In contrast, HIV is currently incurable; however, antiretroviral therapy (ART) can suppress the virus. Adhering to ART protocols can significantly extend the lifespan and improve the quality of life. TB and HIV are complex structure diseases, as their interrelation intensifies the progression of each condition, which increases the mortality rates. As a result, their co-infection is becoming a global issue8. Due to the impact of HIV on the immune system, individuals with HIV are more susceptible to opportunistic infections, including TB. In this context, TB is considered an opportunistic infection, as it exploits the weakened immune defenses of HIV-positive individuals. According to reports from health organizations such as WHO and CDC, the mortality rate is controlled by implementing healthcare and following treatment strategies. However, it can still be high in regions with limited access to healthcare and in areas where precautionary measures are not addressed properly9. This review examines recent progress in the pathogenesis, examination, and therapy of TB-HIV co-infection and discusses the current challenges to achieving global control of this dual epidemic. Co-infection treatment is a combination of ART therapy and anti-TB medication, which leads to drug-drug interaction affecting treatment outcomes and improving the patient’s well-being10. Observational studies indicate that raising CD4 counts in individuals who are taking ART and anti-TB treatment underscores the need for prompt and effective management of co-infections to enhance patient outcomes11. Delgado et al.12 examined TB dynamics, showing that combining social programs with 3HP therapy and enhanced diagnosis rates leads to a significant reduction in TB incidence and mortality.

The fractional derivative concept generalizes traditional differentiation, extending it to non-integer orders and applying it to real or complex numbers13. This concept analyzes integrals and derivatives of arbitrary order, proposing more flexible mathematical tools for modeling processes that show memory effect behavior14. Various disciplines, including physics, engineering, and finance, employ fractional derivatives to capture phenomena that traditional integer-order derivatives cannot effectively describe15. Additionally, the introduction of a Caputo-type fractional derivative with adjustable memory effects is key to modeling complex systems that exhibit short memory, offering a distinct mechanism to represent local memory influences16. By using fractional derivatives, researchers can reveal hidden dynamics in infections that are not detectable with integer-order derivatives17.

Fractional-order derivatives are used in this study to represent the time-dependent dynamics and memory effects in disease progression and treatment responses. They allow for a more precise depiction of the delayed and gradual treatment effects that integer-order models cannot fully capture. Although the treatment durations and effectiveness for HIV and TB vary, fractional orders help account for these differences, including the extended treatment time for TB due to drug resistance. The specific fractional orders chosen align with empirical observations, ensuring a more accurate modeling of disease progression and treatment outcomes.

Ullah et al.18 proposed a fractional-order model for HBV-HIV co-infection in Taiwan, showing that effective HBV vaccination enhances co-infection dynamics. Their model, validated with real data, uses reproduction numbers to evaluate equilibrium stability and predict outcomes, with fractional derivatives enhancing the accuracy of modeling complex disease behaviors. Ullah et al.19 proposed a nonlinear fractional-order model in the Caputo sense to study TB dynamics using data from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan (2002-2017). The utilization of fractional derivatives improves the model’s fit to real data, offering deeper insights into TB dynamics compared to classical approaches. Liu et al.20 employ a nonlocal operator characterized by a Mittag–Leffler kernel to investigate a TB-HIV co-infection model that considers the dynamics of recurrent tuberculosis and reinfection from external sources. The study demonstrates the existence, uniqueness, and stability of solutions using various mathematical techniques, and provides numerical results for various fractional and fractal orders using the Adams–Bashforth method. In these models, researchers have analyzed the basic reproduction number to measure contagiousness, evaluated equilibrium point stability, and studied how fractional operators influence transmission dynamics. Techniques used in fractional models for co-infection dynamics include the Caputo fractional derivative, Krasnoselskii fixed result, Laplace–Adomian decomposition, Hyers–Ulam stability criteria, Banach fixed point theorem, methods like NSFD and TLPM, and the Adam–Bash fourth technique. These techniques have been utilized to explore the existence and uniqueness of solutions and to depict the numerical simulations. Comprehensively, these studies showcase the role of fractional calculus in understanding the pattern of co-infection21.

Researchers are also showing interest in developing co-infection disease models using fractional calculus. Aggarwal et al.22 proposed a dual infection model and separately discussed both diseases. Numerical simulations highlight the importance of combining detection efforts with treatment to reduce co-infection. Pinto and Carvalho23 developed one of the foundational models for capturing the dynamics of co-infection transmission. Their study covers different behavior of the model for various values of \(\alpha \in [0.78, 1.0]\). Their model examines vertical HIV transmission and treatment strategies for both diseases. Mallela et al.24 explore the co-infection dynamics. Their studies show that taking HIV treatment and TB therapy simultaneously can reduce the mortality rate. Momoh et al.25 introduced a mathematical model to describe the transmission dynamics of HIV/AIDS and TB co-infection, designed to guide researchers and policymakers in optimizing the allocation of resources for prevention and treatment efforts. Azeez et al.26 presented a TB-HIV co-infection model identifying two equilibria: disease-free (stable when \(R<1\)) and endemic (stable when \(R>1\)). Simulations reveal that HIV increases TB risk, with susceptible individuals eventually converging to the total population as the diseases decline. Moya et al.27 propose an optimal control model to mitigate MDR-TB and XDR-TB, incorporating HIV/AIDS and diabetes, and highlight the most efficient strategy for reduction. Awoke and Kassa28 developed a co-infection model for HIV/TB that includes prevalence-dependent behavior and treatment strategies. Their simulations showed that optimal prevention and treatment controls could reduce prevalence to below 3% within 10 years, with treatment being more effective than prevention alone. Teklu et al.29 show that implementing a mix of protective measures, COVID-19 vaccination, and treatment is highly effective in controlling the spread of the HBV and COVID-19 co-epidemic.

Over time, various studies have explored TB’s epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment approaches, highlighting its intricate dynamics. Sulayman et al.30 analyze a deterministic TB transmission model, emphasizing the impact of an imperfect vaccine and reinfection. They conclude that while such vaccines reduce transmission, their efficacy and coverage are crucial for effective control. Das et al.31 investigate a SEIR TB model with time-varying boundaries, analyzing stability at disease-free and endemic points based on the reproduction number and bifurcation behavior. Kuddus et al.32 present a two-strain DS (Drug-Susceptible) and DR (Drug-Resistant) TB model, demonstrating that increased drug use and inadequate treatment drive the rise of drug resistance and the co-existence of strains. Similarly for HIV, Huo et al.33 propose a new HIV/AIDS model with a treatment compartment, showing that the disease-free equilibrium is stable when \(R_0\) is less than one, and the endemic equilibrium is stable when \(R_0\) exceeds one, supported by numerical simulations. D’Orso et al.34 investigate viral dynamics models for HIV-1 (Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1), focusing on latent reservoirs and their impact on persistent infection. The models provide insights into viral load decay, the formation of latent reservoirs, and the potential effectiveness of strategies like latency-reversing agents and gene therapies. Teklu et al.35 develop a model showing that a combination of preventive and therapeutic controls effectively reduces HIV/AIDS-TB co-infection, with therapeutic controls more effective for the infected. Teklu et al.36 present a model for HBV and TB co-infection, demonstrating that combining protective and therapeutic strategies reduces co-infection, with HBV treatment being the most cost-efficient.

Building on the referenced articles, we will establish and explore a fractional-order approach to modeling the HIV-TB co-infection hypothesis using the Caputo derivative, incorporating real data from the USA. Our mathematical modeling approach is unique in that it integrates treatment strategies for both diseases, a novel aspect not previously addressed in HIV-TB co-infection models, and also includes the chronic stage of TB. This integration will provide more precise and region-specific insights, distinguishing our study from earlier research.

This paper is structured into eight sections. Section “Fractional order model assumptions and formulation” comprehensively covers the basic definitions, model formulation, existence and uniqueness of solution, and finally positivity and boundedness of solution. Section “The equilibrium points within the co-infection framework” covers the equilibrium point. Reproduction numbers for HIV and TB are discussed in section “Basic reproduction number”. Section “Stability assessment” comprehensively covers the stability analysis and 3D graphs under various conditions. Parameter estimation is done in section “Parameter estimation”. Section “Numerical simulations” comprises the numerical simulation. In the last section “Conclusion”, we end our study with a conclusion.

Fractional order model assumptions and formulation

This section introduces the core definitions of the Caputo fractional derivative and outlines the transition from integer-order to fractional-order model formulation.

Definition 1

(37) The fractional derivative, as per Caputo’s definition, is of order \(\mathfrak {n}>0\), \(\mathfrak {n} \in R^+\) is

where \(0< \mathfrak {n} <1\). Subsequently, it’s obvious that \(^C D^{\mathfrak {n}}_t \mathsf {f(t)}\rightarrow \mathsf {f'(t)}\) if \(\mathfrak {n} \rightarrow 1\).

Definition 2

The integral operator of the Caputo fractional derivative can be defined as

for \(0< \mathfrak {n} < 1\), \(t > 0\).

Definition 3

The Laplace transform of the Caputo fractional derivative applied to the function f(t) is expressed as

Model formulation

In this subsection, we comprehensively explain the formulation of our dual infection framework. Co-infection with HIV and TB is widely acknowledged as a serious health condition, regardless of the HIV stage. And we conclude that if the infected individual adheres to the medication regimen and precautionary measures can enable them to lead a normal lifespan.

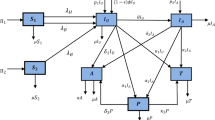

In this paper we split the individuals into nine compartments namely susceptible S(t), individuals suffering from TB \(I_T(t)\), chronic TB individuals \(C_T(t)\), TB individuals getting TB treatment \(T_T(t)\), members recovered from TB \(R_T(t)\), members infected with HIV \(I_H(t)\), people having co-infection \(I_{TH}(t)\), individuals reached the AIDS stage \(A_H(t)\) and finally the treatment of HIV \(T_H(t)\).

In our presented framework, the individuals under consideration are entering the S(t) compartment at a constant rate \(\Omega\). It is also presume that the natural death rate is represented by \(\mu\). All individuals within their designated compartments are subject to natural death at a uniform rate \(\mu\). Also assumed that infected TB and HIV individuals can become co-infected at the same time. Furthermore, keeping in mind that the therapy of HIV takes longer time as compared to TB therapy. The TB virus can be transmitted to other classes if they came in contact with the infected classes, given as

Additionally, HIV can be transmitted to vulnerable individuals who come into contact with those who have HIV. We also assume that individuals undergoing HIV treatment adhere to preventive measures to completely avoid transmitting HIV. Therefore, the infection rate for HIV is described as

\(\lambda _t\) and \(\lambda _H\) are the transmission rate at which the susceptible head to the \(I_T\) and \(I_H\) respectively. \(I_T\) individuals moves to the \(C_T\) with the progression rate \(\alpha _1\) and some switch to the \(T_T\) at the rate of \(\alpha _2\), also some of the \(C_T\) moves to the \(T_T\) at the rate of \(\alpha _3\). Some of the \(C_T\) also have the probability to get infected with HIV as their immune system is vulnerable and shift to the \(I_{TH}\) at the rate of \(\lambda _H\). Furthermore, co-infected individuals might also move to the \(C_T\) at the rate of \(\alpha _4\). Finally, the \(T_T\) shift to the \(R_T\) with the rate of \(\gamma _2\) after getting the TB therapy.

Individuals in the S(t) are at risk of contracting HIV, moving to the \(I_H\) with a force of infection \(\lambda _H\). Those in \(I_H\) may transition to the co-infected class \(I_{TH}\) due to exposure to TB-infected individuals with the force of infection \(\lambda _T\). From \(I_H\), progression can lead to treated HIV infection, \(T_H\), at the rate of \(\sigma _3\), or advance to the AIDS stage at rate \(\sigma _1\). Individuals in \(A_H\) after exposure to TB may shift to \(I_{TH}\) at rate \(\lambda _T\), while those undergoing HIV treatment could move to \(T_H\) at rate \(\gamma _1\). The co-infected class \(I_{TH}\) also faces progression to AIDS at rate \(\sigma _2\). Furthermore, TB-recovered individuals remain susceptible to HIV reinfection, interacting with \(I_H\) at rate \(\lambda _H\). Figure 1 illustrates the model’s hypotheses and propagation processes using a flowchart.

Examine the non-linear model that follows:

with initial conditions

Adding up all the equations presented in (2.4) yields:

The model (2.4) or its modified iteration, as specified by

where Y: \([0, \infty )\rightarrow \mathbb {R}^{9}\) and J: \(\mathbb {R}^{9}\) \(\rightarrow\) \(\mathbb {R}^{9}\) in a manner that

where \(i=1,2,3,\ldots 9.\)

Existance and uniqueness of solution

Theorem 2.1

In (2.4), J preserves Lipschitz continuity with respect to Y.

Proof

Suppose the line segment \(L\) in \(\mathbb {R}^{9}\) associates points \(Y_1\) and \(Y_2\) given as \(L(Y_1,Y_2,q) = [ {Y_1+q(Y_2-Y_1);}\) \(q\in [0,1]\), \((Y_2, Y_1)\in\) \(\mathbb {R}^{9}\)], for \(\varepsilon \in L(Y_1,Y_2,q)\) by employing the Mean Value Theorem, we get

where \(\Vert \ J'(\epsilon,Y_2, Y_1) \Vert _{\infty } = \Vert \sum _{i=1}^{n} (\tau J_i(\varepsilon )(Y_2-Y_1)e_i\Vert _{\infty }\) \(\le \Vert \sum _{i=1}^{n}\tau J_i(\varepsilon )\Vert\) \(\Vert Y_2-Y_1\Vert _{\infty },\) since all partial derivatives of \(J_i\) are bounded,\(\exists\) \(\tau >0\); \(\forall\) \(\tau (Y_1,Y_2,\varepsilon )\subseteq \mathbb {R}^{9} \),\(\Vert \sum _{i=1}^{n}\tau J_i(\varepsilon )\Vert \le \tau\), implies that

Therefore, for a given \(Y\), \(J\) exhibits Lipschitz continuity. \(\square\)

Theorem 2.2

Provided that the condition (2.9) is met for the initial data specified for J, a unique solution to the model (2.4) can be found when

Proof

Considering that \(J(0, Y(0)) = 0\), it is necessary to demonstrate that \(Y(\varepsilon )\) align with system (2.4) if and only if it fulfills

By applying (2.2) to system (2.7), we obtain

Given \(J(0, Y(0)) = 0\) and \(Y(0) = Y_0\), Eq. (2.10) is thereby satisfied.

Alternatively, assuming that the solution (2.10) holds for \(Y(t)\) with \(Y(0) = Y_0\), this condition results from the requirement \(J(0, Y(0)) = 0\). Therefore, the initial data satisfies the solution representation,

Let \(L\) be defined as \(L: D(\eta, \mathbb {R}^{9}) \rightarrow D(\eta, \mathbb {R}^{9})\), where \(\eta = (0, N)\).

Then (2.11) becomes

Let \(\Lambda : D[0,N] \rightarrow D[0,N]\) be defined in a way that \(\Lambda w = u\), where

where f(t,\(\rho\)): \(\eta \times \eta \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) is the kernel of \(\Lambda\), continuous in the region \(\sigma =\eta \times \eta\). Then \(\exists\) \(f_0\in \mathbb {R}\) such that \(|f(t,\rho )| \le f_0\), \(f(t,\rho )\in \eta \times \eta\) and \(sup_{t,\alpha }|f(t,\rho )| \le f_0\)

Since Y(\(\rho\)) and f(t,\(\rho\)) are continuous, therefore \(\left\| \int _{0}^{t}f(t,\rho )Y(\rho )d\rho \right\| _\eta\) = \(sup_{t\in \eta }\left\| \int _{0}^{t}f(t,\rho )Y(\rho )d\rho \right\| _\eta\) \(\le sup_{t\in \eta } \int _{0}^{t}\left\| f(t,\rho )\right\| \left\| Y(\rho )\right\| d\rho,\) hence

with \(Y(t)\in D(\eta,\mathbb {R}^{9})\), \(f(t,\rho )\in D(\eta ^2,\mathbb {R}^{9})\) such that:

by (2.12) we have

\(\left\| L[Y_1(t)] - L[Y_2(t)]\right\| _\eta \le \left\| \frac{1}{\Gamma (\alpha )}\int _{0}^{t}(t-\rho )^{\alpha -1} \left( J(t,Y_1(t)) - J(t,Y_2(t))\right) d\rho \right\| _\eta .\)

Applying conditions (2.8) and (2.13), we obtain

Therefore, \(L\) would lead to a contradiction if \(\tau (B^* \frac{1}{\Gamma (\alpha )}) < 1\). Therefore, the Banach Contraction Principle confirms the existence of a unique solution for the system (2.4). \(\square\)

Positivity and boundedness of solutions

In the presented framework, every component incorporates the human community. Therefore, it is crucial to show that all compartments \(S(t),I_H(t), I_T(t), I_{TH}(t),A_H(t), C_T(t), T_H(t), T_T(t),\) and \(R_T(t)\) are non-negative for all \(t \ge 0\). Consequently, we examine the feasible region as follows:

Thus with the territory M we’ve the proceeding results.

Theorem 2.3

With the model equation (2.4) and the specified initial conditions (2.5), the system (2.4) is positive for every \(t\ge 0\) .

Proof

Assume \(\bar{s}\) be supremum of a set for which certain condition hold

Then clearly \(\bar{s}\ge 0\). Suppose that \(S(0)\ge 0\)

Put \(g(t)=(\lambda _H+\lambda _T+\mu )\) . Multiplying both side by

The previous equation simplifies to

Integrating both sides over the interval \(t=0\) to \(t=\bar{s}\), we derive

We apply multiplication to both sides with

to get

Given that \(S(0) \ge 0\), the positive terms within S are also positive. Likewise, we can prove that the quantities \(I_H\), \(I_T\), \(I_{TH}\), \(A_H\), \(C_T\), \(T_H\), \(T_T\), and \(R_T\) remain non-negative for all \(t \ge 0\). Additionally any solution of model (2.4) satisfies the consequences given \(S(0) \ge 0\), \(I_H(0) \ge 0\), \(I_T(0) \ge 0\), \(I_{TH}(0) \ge 0\), \(A_H(0) \ge 0\), \(C_T(0) \ge 0\), \(T_H(0) \ge 0\), \(T_T(0) \ge 0\) and \(R_T(0) \ge 0\).

This completes the positivity proof. \(\square\)

Boundedness of solutions

Theorem 2.4

All solutions to system (2.4) remain within bounds.

Proof

The variable N represents the under consider individuals and is defined as

Differentiating w.r.t “t”, we get

using the equation, we get that

Presume, under any initial setup, \(N(0)\le \frac{\Omega }{\mu }\) under which

We assert that

It is implied by (2.14) that

Incorporating the Gronwall’s inequality, we get

Subsequently \(N(t)\le \frac{\Omega }{\mu }\) \(\forall\) \(t\ge 0\), whenever

Clearly

This shows that N(t) and all other components \(S(t),I_H(t), I_T(t),I_{TH}(t),A_H(t),C_T(t),T_H(t),T_T(t)\) and \(R_T(t)\) are bounded. \(\square\)

The equilibrium points within the co-infection framework

In analyzing the co-infection model, achieving equilibrium points involves simply setting the system (2.4) to zero. The disease-free condition of the framework is characterized as

The point of equilibrium indicating the presence of the illness is signified by

where

where \(K_1=\sigma _1+\sigma _3+\mu +\mu _H, \,\, K_2=\alpha _2+\alpha _1+\mu +\mu _T, \,\, K_3=\sigma _2+\alpha _4+\mu +\mu _{TH}, \,\,K_4=\gamma _1+\mu\) \(+\delta _1,\,\, K_5=\alpha _3+\mu +\delta _2, K_6=\mu +\delta _4, \,\, K_7=\gamma _2+\mu +\delta _3.\)

Basic reproduction number

A fundamental idea in epidemiology, the basic reproduction number, or \(R_0\), characterizes the ease with which an infectious illness can spread. In a community where everyone is vulnerable, it shows the mean new infection rate brought on by one diseased individual. In advanced epidemiological modeling, especially within compartmental models such as the next-generation matrix approach, \(R_0\) can indeed be determined by the spectral radius of the matrix product \(FV^{-1}\). Thus, \(R_0\) can indeed be expressed as:

where \(\rho\) signifies the dominant eigenvalue, obtained via the next-generation procedure18. This technique is particularly advantageous for intricate diseases and models with numerous compartments and transitions.

and

Here are the necessary reproduction numbers:

where \(R_T\) indicating the mean number of follow-up TB cases caused by one infectious person in a population. Similarly, \(R_H\) signifies the reproduction number for HIV, representing the mean number of follow-up HIV cases caused by one infectious person.

Stability assessment

In this part, we use the Lyapunov function construction and Routh–Hurwitz criteria to show both local and global stability of the disease-free equilibrium point \((E^0)\) of the model.

Local stability

Theorem 5.1

The equilibrium state without disease remains locally asymptotically stable if \(R_0\) is less than 1, but it becomes unstable if \(R_0\) greater than 1.

Proof

The Routh–Hurwitz method is used to assess the local stability of the model at \(E^0\). The Jacobian matrix at this point is defined as follows:

If all of the eigenvalues of the disease-free equilibrium point have negative real components, then the equilibrium point behaves in a locally asymptotically stable manner. The following is the typical equation:

The model’s unique eigenvalues are

The characteristic equations may be used to find the matrix’s remaining eigenvalues. Let us now examine the equations derived from this process (5.1)

In these equations, it is evident that \(K_1,K_2,\ldots,K_8\) have positive values. When \(R_0<1\), the coefficients \(\lambda _1, \lambda _2,\ldots \lambda _7\) are also positive, making the coefficients overall positive. The Rough Hurwitz criterion18 for a second-order polynomial can thus be easily satisfied using these coefficients. Therefore, at the DFE point, the model (2.4) is locally asymptotically stable, given that \(R_0\) is less than 1. \(\square\)

Global stability

Theorem 5.2

The disease-free equilibrium, specified in framework (2.4) and Eq. (3.1), is globally asymptotically stable as long as the \(R_0\) remains under 1.

Proof

To illustrate the globally asymptotically stable of \(E^0\), we develop a Lyapunov function \(\Lambda :\Omega \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\)15,18

The time dependent Caputo fractional derivative of \(\Omega\) is

Putting the values from (2.4),we get

Through simplification, we get

Clearly

so

\(^C\mathcal {D}^{\alpha }_t \Lambda = 0 \Leftrightarrow S=S^0,I_H=I_H^0,I_T=I_T^0,I_{TH}=I_{TH}^0,A_H=A_H^0,C_T=C_T^0,\) \(T_H=T_H^0,T_T=T_T^0\, and \, R_T=R_T^0.\) According to LaSalle’s principle21 it is narrated that \(E^0\) exhibits globally asymptotically stable when \(R_0\) is less than 1. As a result, the disease no longer affects human populations. The stability of the suggested model mentioned in Fig. 2. \(\square\)

Parameter estimation

The nonlinear least squares curve fitting method is used in this part to estimate the framework’s variables18. We employ MATLAB software to perform the estimation analysis, utilizing its advanced computational and optimization tools to ensure precise parameter estimation. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)38 provides data on TB-infected infections in the United States from 1999 to 2022. The total cases are calculated for the overall population, as the CDC data is given per 100,000 people. The life span and total population of the United States are reported as 77 years and 279,181,581, respectively39. The mortality rates and the rate at which the population enters \(\Omega\) are calculated based on these statistics. In Fig. 3, the model curve is shown fitted with cumulative infected cases, while Table 1 provides the projected and considered values of the parameters involved in the model equations. The parameters to be estimated, including \(\beta _T\), \(\beta _H\), \(\gamma _1\), \(\gamma _2\), \(\alpha _2\), and \(\alpha _3\), play a vital role in analyzing disease dynamics and guiding interventions. However, limitations in the data, such as missing, inconsistent, or hard-to-collect information, can introduce uncertainty, influencing the model’s reliability. Additionally, the accuracy of parameter estimation depends on the availability of comprehensive, high-quality data, which is essential for improving predictions and supporting effective public health decisions.

The analysis of the model faced challenges due to its complexity, especially in modeling the interactions between diseases like HIV and TB, requiring advanced numerical methods for accurate solutions. Data-related issues, such as inconsistency and incompleteness, complicated model calibration and parameter estimation. Additionally, interpreting the results, particularly in the case of co-infections, demanded careful attention to the model’s assumptions and limitations.

Numerical simulations

This section contain how the considered numerical scheme is applied to develop model as well as the graphical results of the model equations. A detail discussion of the model phase poraits is also included in this section and the simulation are done by using the MATLAB software.

Numerical scheme

The following is how the system can be described using the fundamental theorem of fractional calculus:

\(Given \quad t = t_{m+1} \quad \text {and} \quad n \in R, \quad \text {with} \quad h = \frac{T}{R}\). We find

Using the interpolation polynomial the function \(Q(\phi, \varphi (\phi ))\) can be approximated over \([t_l, t_{l+1}]\). We get

Finally we get the the approximation

Hence, for the given model we establish the formula

By continuing forth in this way, we can ascertain the remaining model equations.

Results and discussion

This subsection deals with the numerical simulations and disease impact when we vary the reproduction number. These simulations are meant to facilitate analytical assessment and to analyze the possible effects of fractional order and treatment on the US population. The numerical simulations for the co-infection model are executed with the Adams–Bashforth–Moulton method in MATLAB. The initial conditions utilised in the numerical analysis are set up such that the American population is equal to the cumulative sum of the initial states39. As we are taking real data of United States so according to that data the model begins with the initial conditions \(S(0) = 279145000, \quad I_H(0) = 23495, \quad I_T(0) = 10000, \quad I_{TH}(0) = 1000, \quad A_H(0) =800,\) \(C_T(0) = 600, \quad T_H(0) = 200,\quad T_T(0) = 200, \quad R_T(0) =286.\)

The Adams–Bashforth–Moulton method enhances accuracy, stability, and convergence, making it efficient for smooth problems without requiring Jacobian calculations. It is particularly valuable for parameter estimation and effectively modeling real-world dynamics. This study provides crucial insights into the complex interactions of HIV/TB, advancing future research and public health strategies. The findings offer a comprehensive framework for understanding multi-disease dynamics, which simpler models often neglect, and contribute to data-driven approaches in epidemiology, particularly in resource-limited settings.

The arc showing the behavior of compartments under various starting assumptions when \(R<1\) is shown in Fig. 4a–i. It is noted that despite the variation in the beginning conditions, the arc of the infected section converges to a disease-free state. It can be observed that decline is sharp at the higher order of \(\alpha\) as compared to lower order. It is noteworthy that when the fractional order reaches the integer order, the treatment of individuals with HIV and TB converges to the disease-free state. Essentially, this insight emphasizes a key point where the fractional-order model, though more complex, converges with the integer-order model in predicting the eradication of the disease.

To fully understand the implications of fractional order, we create two cases of reproduction numbers. We have two reproduction numbers: one for TB and another for HIV. First, we consider the case when \(R_T<1\) and \(R_H>1\). By looking at the graph, we observe that for the higher fractional derivative order, the infected classes show peak behavior (Fig. 5). By the same token, for lower fractional derivative order, all the compartments depict the endemic behavior. It is noteworthy that when the fractional order reaches the integer order, the arc exhibits a significant decline, subtly suggesting that adherence to treatment protocols can lead to recovery. Likewise, when \(R_T>1\) and \(R_H<1\), it is observed that for higher orders, the trajectory of compartments shows contrasting behavior as depicted in Fig. 6a–i. It is observable that for the given fractional derivative order, all the compartments picture the disease-free state. Figures 5 and 6 display the incidence of participants getting affected by TB and HIV over the span of 50 years, also showing the impact of HIV treatment and TB recovery. When \(\alpha\) attains the integer order in both cases, the treatment graphs show a transition to the disease-free state.

The simulation investigates how varying the treatment parameter \(\gamma _1\) impacts disease progression. Figure 7a–d illustrate that increasing \(\gamma _1\) accelerates the decline in infection rates and leads to a quicker approach to a disease-free state. These results highlight the potential of optimizing treatment parameters to improve infection control and support efforts toward disease elimination.

Figure 8 depicts that although the curves initially approach a disease-free state, they eventually converge towards an endemic state over time. Figure 8a–d reveal that lower \(\alpha _3\) values result in a slower shift to the endemic state, while higher \(\alpha _3\) values expedite this transition. The results suggest that despite the role of \(\alpha _3\) in determining TB treatment effectiveness, treatment alone may not fully eradicate TB. This indicates a need for refining treatment approaches or introducing additional strategies to achieve complete disease elimination.

Figures 7 and 8 highlight how fractional orders affect the treatment dynamics of HIV and TB. They demonstrate the influence of memory effects on the pace at which treatments take effect. For TB, the model reveals slower treatment responses, particularly due to drug resistance, while HIV treatment shows quicker adjustments. These figures underscore the significance of fractional orders in capturing the time-dependent nature of disease progression and treatment, offering a more accurate representation of treatment effectiveness.

The basic reproduction number \((R_0)\), is critical for understanding epidemic dynamics. When \(R_0>1\), the disease spreads rapidly, as shown by rising case numbers, while \(R_0<1\) indicates a decline in infections, reflected by a downward trend. The graph demonstrates how \(R_0\) influences disease transmission, offering insights into controlling and managing outbreaks. Recognizing this threshold helps guide targeted public health strategies to prevent or mitigate the spread.

Conclusion

In this analysis, a pioneering fractional model for the interactions of HIV-TB co-infection with treatment is examined and investigated. The necessary conditions for the existence and uniqueness of the solution of the model are discussed in detail. The model equilibrium states, including the disease-free and endemic equilibrium states, are presented. The next-generation methodology is employed to calculate the basic reproduction number. Moreover, the local and global stability of the disease-free equilibrium is analyzed, and it is concluded that the equilibrium is asymptotically stable for \(R_0\) less than 1 and unstable for \(R_0\) greater than 1. Significant findings and contributions derived from the simulations are summarized as follows:

i. Real TB data from the CDC, spanning from 1999 to 2022, is used to formulate the model. The model formulation and investigation are performed through the estimation of essential parameters for each disease and its co-infection based on real data.

ii. It is observed that the fractional derivative significantly impacts the dynamics of the diseases within each epidemiological compartment over time. The differences observed in simulations using the fractional derivative are attributed to the memory effect, which is absent in classical integer-order operators.

iii. The total infected population with TB and HIV, shown for different susceptibility parameters, is demonstrated to decrease as efforts to combat secondary infections are intensified, resulting in a marked reduction in new co-infection cases.

It is concluded that effective HIV prevention significantly lowers the rate of TB co-infections, and efficient TB treatment boosts the immune system, thereby reducing the risk of co-infections with opportunistic infections such as HIV/AIDS. Figures 4 and 5 highlight the importance of \(R_0\) and demonstrate its impact on disease transmission dynamics. These insights allow for a comprehensive assessment of the impact of different strategies.

Some limitations of this study are identified. To streamline the model, the TB vaccination aspect is excluded. Additionally, insufficient data on immunity between HIV and TB resulting from vaccination or previous infection is noted. This presents an opportunity to improve the model. Therefore, with a clearer understanding of disease interactions, further investigation into this subject is planned.

To enhance the study in the future, it would be beneficial to apply sensitivity analysis to evaluate the influence of parameter fluctuations on the transmission patterns of HIV and TB. Additionally, integrating optimal control methods could provide a deeper understanding of the most efficient strategies for managing the spread of these infections. Moreover, incorporating delayed differential equations (DDEs) would allow for the modeling of time-dependent factors, such as delays in treatment responses or disease progression, thereby offering a more accurate depiction of the co-infection dynamics of HIV and TB.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article.

References

Khan, M. A. et al. A mathematical model of tuberculosis (TB) transmission with children and adults groups: A fractional model. AIMS Math. 5(4), 2813–2842 (2020).

World Health Organization. Fact Sheets: Shigellosis (2024). https://www.who.int/mediacentre/fact-sheets/fs360/en/

Moya, E. D., Pietrus, A. & Oliva, S. M. A mathematical model for the study of effectiveness in therapy in tuberculosis taking into account associated diseases. Contemp. Math. 2, 77–102 (2021).

Shaw, G. M. & Hunter, E. HIV transmission. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2(11), a006965 (2012).

UNAIDS. Global HIV statistics 2024 (2024). https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2024/global-hiv-statistics, accessed: 2024-08-25

Omame, A. et al. Understanding the impact of HIV on mpox transmission in an MSM population: a mathematical modeling study. Infect. Dis. Model. 9, 1117–1137 (2024).

Aris, R. Mathematical Modelling Techniques (Courier Corporation, 1994).

UNAIDS. HIV/AIDS global fact sheet (2024).

Letang, E. et al. Tuberculosis-HIV co-infection: progress and challenges after two decades of global antiretroviral treatment roll-out. Archivos de bronconeumologia 56(7), 446–454 (2020).

Granich, R. et al. Prevention of tuberculosis in people living with HIV. Clin. Infect. Dis. 50(Suppl 3), S215–S222 (2010).

Soni, A. et al. A hospital based observational study on HIV-TB coinfection. Access Microbiol.[SPACE]https://doi.org/10.1099/acmi.0.000787.v1 (2024).

Delgado Moya, E. M. et al. A mathematical model for the impact of 3hp and social programme implementation on the incidence and mortality of tuberculosis: Study in brazil. Bull. Math. Biol. 86(6), 1–25 (2024).

Podlubny, I. Fractional Differential Equations: An Introduction to Fractional Derivatives, Fractional Differential Equations, to Methods of their Solution and Some of Their Applications (Elsevier, 1998).

Butt, A. R., Saqib, A. A., Alshomrani, A. S., Bakar, A. & Inc, M. Dynamical analysis of a nonlinear fractional cervical cancer epidemic model with the nonstandard finite difference method. Ain Shams Eng. J. 15(3), 102479 (2024).

Sinan, M., Leng, J., Anjum, M. & Fiaz, M. Asymptotic behavior and semi-analytic solution of a novel compartmental biological model. Math. Model. Numer. Simul. Appl. 2(2), 88–107 (2022).

Butt, A. R. et al. Investigating the fractional dynamics and sensitivity of an epidemic model with nonlinear convex rate. Results Phys. 54, 107089 (2023).

Aggarwal, R. & Raj, Y. A. A fractional order HIV-TB co-infection model in the presence of exogenous reinfection and recurrent TB. Nonlinear Dyn. 104, 4701–4725 (2021).

Ullah, M. A., Raza, N., Omame, A. & Alqarni, M. A new co-infection model for HBV and HIV with vaccination and asymptomatic transmission using actual data from Taiwan. Phys. Scr. 99(6), 065254 (2024).

Ullah, S., Khan, M. A. & Farooq, M. A fractional model for the dynamics of TB virus. Chaos Solitons Fractals 116, 63–71 (2018).

Liu, X., Ahmad, S., ur Rahman, M., Nadeem, Y. & Akgül, A. Analysis of a TB and HIV co-infection model under Mittag–Leffler fractal-fractional derivative. Phys. Scr. 97(5), 054011 (2022).

La Salle, J. P. The Stability of Dynamical Systems (SIAM, 1976).

Aggarwal, R. et al. Dynamics of HIV-TB co-infection with detection as optimal intervention strategy. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 120, 103388 (2020).

Pinto, C. M. & Carvalho, A. R. New findings on the dynamics of HIV and TB coinfection models. Appl. Math. Comput. 242, 36–46 (2014).

Mallela, A., Lenhart, S. & Vaidya, N. K. HIV-TB co-infection treatment: Modeling and optimal control theory perspectives. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 307, 143–161 (2016).

Momoh, A. A., Isah, A., Abimbola, N. G. & Mathias, D. Mathematical model for the transmission dynamics of HIV/AIDS and TB co-infection. CaJoST 1(1), 71–82 (2019).

Azeez, A., Ndege, J., Mutambayi, R. & Qin, Y. A mathematical model for TB/HIV coinfection treatment and transmission mechanism. Asian J. Math. Comput. Res. 22, 180–192 (2017).

Moya, E. M. D. et al. Optimal control strategy for the effectiveness of TB treatment taking into account the influence of HIV/AIDS and diabetes. Open J. Math. Sci. 6(1), 76–98 (2022).

Awoke, T. D. & Kassa, S. M. Optimal control strategy for TB-HIV/AIDS co-infection model in the presence of behaviour modification. Processes 6(5), 48 (2018).

Teklu, S. W. Impacts of optimal control strategies on the HBV and COVID-19 co-epidemic spreading dynamics. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 5328 (2024).

Sulayman, F., Abdullah, F. A. & Mohd, M. H. An SVEIRE model of tuberculosis to assess the effect of an imperfect vaccine and other exogenous factors. Mathematics 9(4), 327 (2021).

Das, K., Murthy, B., Samad, S. A. & Biswas, M. H. A. Mathematical transmission analysis of SEIR tuberculosis disease model. Sens. Int. 2, 100120 (2021).

Kuddus, M. A., McBryde, E. S., Adekunle, A. I., White, L. J. & Meehan, M. T. Mathematical analysis of a two-strain tuberculosis model in Bangladesh. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 3634 (2022).

Huo, H.-F., Chen, R. & Wang, X.-Y. Modelling and stability of HIV/AIDS epidemic model with treatment. Appl. Math. Model. 40(13–14), 6550–6559 (2016).

D’Orso, I. & Forst, C. V. Mathematical models of HIV-1 dynamics, transcription, and latency. Viruses 15(10), 2119 (2023).

Teklu, S. W., Abebaw, Y. F., Terefe, B. B. & Mamo, D. K. HIV/AIDS and TB co-infection deterministic model bifurcation and optimal control analysis. Inform. Med. Unlocked 41, 101328 (2023).

Teklu, S. W. & Abebaw, Y. F. Analysis of the HBV and TB coinfection model with optimal control strategies and cost-effectiveness. Discrete Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2024(1), 8811930 (2024).

Caputo, M. & Fabrizio, M. A new definition of fractional derivative without singular kernel. Prog. Fract. Differ. Appl. 1(2), 73–85 (2015).

Center for Disease Control, Prevention, Reported tuberculosis in the United States, 2022 (2022). https://www.cdc.gov/tb/statistics/reports/2022/table1.htm

Population Pyramid, United States of America 1999 (1999). https://www.populationpyramid.net/united-states-of-america/1999

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University, KSA for funding this work through Large Research Project under grant number RGP.2/575/45.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the preparation, design, and study of the problem. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Raza, N., Irum, S., Niazai, S. et al. A mathematical framework of HIV and TB co-infection dynamics. Sci Rep 15, 11465 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91871-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91871-7