Abstract

Kawasaki disease (KD) is a syndrome of acute systemic vasculitis commonly observed in children. Due to its unclear pathogenesis and the lack of specific diagnostic markers, it is prone to being confused with other diseases that exhibit similar symptoms, making early and accurate diagnosis challenging. This study aimed to develop an interpretable machine learning (ML) diagnostic model for KD. We collected demographic and laboratory data from 3650 patients (2299 with KD, 1351 with similar symptoms but different diseases) and employed 10 ML algorithms to construct the diagnostic model. Diagnostic performance was evaluated using several metrics, including area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUC). Additionally, the shapley additive explanations (SHAP) method was employed to select important features and explain the final model. Using the Streamlit framework, we converted the model into a user-friendly web application to enhance its practicality in clinical settings. Among the 10 ML algorithms, XGBoost demonstrates the best diagnostic performance, achieving an AUC of 0.9833. SHAP analysis revealed that features, including age in months, fibrinogen, and human interferon gamma, are important for diagnosis. When relying on the top 10 most important features, the model’s AUC remains at 0.9757. The proposed model can assist clinicians in making early and accurate diagnoses of KD. Furthermore, its interpretability enhances model transparency, facilitating clinicians’ understanding of prediction reliability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute systemic vasculitis syndrome commonly observed in children, which has become a leading cause of acquired heart disease in children worldwide1,2. Without timely intervention, patients face an extremely high risk of coronary artery lesions, and potentially leading to angina pectoris, myocardial infarct, even sudden death at any time3,4. Therefore, accurate diagnosis of KD in the initial stage of the disease is importance for achieving favorable clinical outcomes5. In statements published by the American Heart Association (AHA) and the Scientific Committee of the Japanese Circulation Society, the diagnosis of KD primarily relies on the patient’s clinical symptoms and laboratory findings6,7. Excluding other diseases is a crucial step in diagnosing KD, as the clinical symptoms of KD patients are atypical and can be easily confused with other pediatric illnesses, causing a high rate of underdiagnosis and misdiagnosis8,9. Consequently, there is an urgent clinical need for a method with high sensitivity and specificity to rapidly differentiate KD from other diseases that exhibit similar symptoms.

ML technology employs statistical methods to analyze large datasets, thereby inferring relationships among the data and integrating them to predict outcomes10. Some researchers are currently investigating the potential application of ML in the diagnosis of KD. By employing logistic regression modeling, a study developed a blood scoring system to differentiate KD from other febrile illnesses, which incorporated eight blood tests, demonstrated 82.4% sensitivity and 83.9% specificity in the validation dataset11. Subsequently, some researchers used linear discriminant analysis to identify KD based on patients’ clinical symptoms and laboratory results12. Based on this foundation, a further study proposed a stepwise KD diagnosis algorithm. This algorithm used a decision tree to re-identify uncertain cases after initial classification, achieving a sensitivity of 96.0% and a specificity of 78.5% on the single-center validation set13. On the multi-center validation set, the sensitivity can reach 91.6%, but the specificity slightly decreases to 57.8%14. Furthermore, additional study has employed the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) and Support Vector Machines (SVM) to identify key features and develop a nomogram model. This model has shown remarkable proficiency in distinguishing between KD and sepsis, with a sensitivity and specificity of 90.4% and 75.0%, respectively15. Recently, a study utilized ensemble learning models to identify KD patients, achieving a sensitivity of 92.5%16. Although previous studies have shown promising results for ML, there is still limited evidence for its application in clinical settings and the development of interpretable diagnostic prediction models. Due to the ‘black box’ nature of ML models, it is difficult to explain why specific predictions are made for patients. The specific patient features that drive these predictions are still unclear10. The limited interpretability of ML methods hinders their application in medical decision-making support17, and the deficiency in intuitive understanding has become a major obstacle to the implementation of ML models in the medical field18.

In this study, we aimed to develop an interpretable ML model for early and accurate diagnosis of KD, and to explain the decision-making process of the model using the SHAP method, exploring the impact of different clinical features on KD diagnosis. Furthermore, to enhance the practicality and clinical applicability of the model, we integrated visualization analysis techniques to develop an online KD-assisted diagnostic tools using the Streamlit framework.

Materials and methods

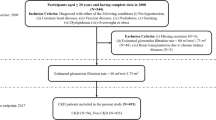

This study focuses on developing interpretable ML models to automatically distinguish KD from other diseases (OD) that with similar clinical symptoms, which may lead to diagnostic confusion. The study design was divided into three stages: (a) data collection and preprocessing; (b) model development; (c) model explanation and web application. The detailed design is shown in (Fig. 1).

Study population

The data used for constructing and validating the models were sourced from Zhejiang University Children’s Hospital, China, from September 2018 to April 2023. Considering that KD primarily affects young children, patients aged 1 month to 12 years were included. The diagnostic criteria for KD followed the AHA’s guidelines, including: (1) lips and oral mucosal abnormal, (2) Rash: maculopapular, diffuse erythroderma, or erythema multiforme-like, (3) bilateral bulbar conjunctival injection without exudate, (4) Erythema and edema of the hands and feet and (5) Cervical lymphadenopathy. The OD group included other febrile disease patients who visited the hospital during the same period and presented with at least one clinical symptom similar to KD, including those with EB viral mononucleosis, erythema multiforme, systemic lupus erythematosus, acute suppurative tonsillitis, adenovirus infection, and mycoplasma pneumonia.

Data collection and preprocessing

In our study, the data are collected from 3675 patients. After excluding 15 samples due to severe data missing, a total of 3650 samples were included, comprising 2299 KD and 1,351 OD. We used demographic characteristics and laboratory test results recorded in the electronic medical record (EMR) to develop our diagnostic models. The need to obtain informed consent was waived by Medical Ethics Committee of Children’s Hospital (Approval Letter of IRB/EC, 2024-IRB-0009-P-01). All of the methods were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

In order to mitigate the impact of multi-collinearity among features on model performance, we conducted Spearman correlation analysis. For any two highly correlated features (correlation coefficient > 0.6), we removed the feature with the lower correlation to the prediction. Additionally, features with missing values > 25% were removed to reduce bias from data incompleteness. Finally, 43 features were utilized to develop the initial diagnostic models. Detailed information on these clinical features is provided in (Table 1).

The dataset was randomly split into a training set (80%, n = 2923) and a test set (20%, n = 727). Specifically, the training set included 1843 KD samples and 1080 OD samples, and the test set included 456 KD samples and 271 OD samples, the two sets were subsequently pre-processed separately. We used the mean imputation method to fill in the missing values for the continuous features. For a discrete categorical feature such as gender, we used one-hot encoding to represent it, where 1 is male and 0 is female. Furthermore, given that the collected data originate from diverse medical instruments, there is a discrepancy in magnitude, and it is necessary to normalize the data. Therefore, we used the min-max normalization method to scale the values to the [0, 1] interval.

Model development

The preprocessed training dataset was utilized to develop the diagnostic model. 10 ML algorithms, including eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)19, Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT)20, K-Nearest-Neighbors (KNN)21, Decision Tree (DT)22, Random Forest (RF)23, Support Vector Machine (SVM)24, Logistic Regression (LR)25, Categorical Boosting (CatBoost)26, Adaptive Boosting (AdaBoost)27, and Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) were employed to predict KD in ill children. To enhance the reliability of the diagnostic model, we employed grid search and five-fold cross-validation to identify the optimal hyperparameters. Using these optimized hyperparameters, we retrained the model on the entire training set and subsequently validated it on a separate test set.

Feature selection and model explanation

Although ML has achieved great success in many fields, its lack of interpretability severely limits its application in safety-sensitive tasks28,29. SHAP is a unified framework introduced by Lundberg to interpret the predictions of ML models30,31,32,33. By calculating the SHAP value of each feature, it quantifies the contribution of the corresponding feature to the model output. Based on these feature contributions, we successively decreased the number of features used in model development from 43 to 5 in an iterative process. During the feature reduction procedure, by comparing the differences in AUC and performance variations among these 10 models, and finally selected the best model for further analysis.

The SHAP method not only quantifies feature importance but also robustly supports model interpretability analysis. At the global level, we comprehensively assessed the impact of each feature on the model’s overall predictions. At the local level, we conducted a detailed analysis of the specific influence of features for individual patients.

Web application development

To enhance clinical application, we developed a Streamlit-based web tool that integrates the final diagnostic model with visualization techniques. This tool can output the probability of a patient developing KD in real-time based on the input of the patient’s clinical feature data, and display a corresponding waterfall plot to visually present the impact of each feature on the model’s decision-making process.

Results

Model performance comparison

This study comprehensively evaluated the specific performance of the 10 models developed based on all features, with the evaluation metrics summarized in (Table 2), and the comparison of the ROC curve is presented in (Fig. 2a). The results indicate that the XGBoost performs the best in all evaluation metrics. To further validate the robustness of this finding, five data splits were performed for repeated experiments, and the average and standard deviation of each evaluation metric for all models across these splits are detailed in Supplementary Table S1. The results in Table S1 show that XGBoost consistently achieves high average values and relatively low standard deviations, demonstrating its consistent performance across the data splits.

During the feature reduction process, guided by the ranking of feature importance, we monitored the changes in the AUC values of the top 5 best-performing ML models, as illustrated in (Fig. 2b). The results demonstrated that the XGBoost still retains nearly the best diagnostic ability after feature reduction. To further explore the influence of the number of features on XGBoost, we plotted its performance metrics across varying numbers of features, as depicted in (Fig. 2c).

Identification of the final model

Figure 2c illustrates the performance variations of the XGBoost model across different numbers of features. It is evident from the figure that as the number of features increases from 10 to 43, the improvement in model performance is not significant. This observation suggests that beyond a certain number of features, the additional information gained does not significantly enhance the model’s predictive capability. Specifically, the model utilizing all features exhibited notable superiority over the models incorporating 5 features (∆AUC = 0.044) and 11 features (∆AUC = 0.01) in the diagnosis of KD. However, in comparison to the model with 10 features, its advantage was not pronounced (∆AUC = 0.007). Here, ∆AUC represents the difference in AUC values between two models, serving as a measure of the performance improvement, a positive ∆AUC indicates that the former model outperforms the latter in terms of performance. The area under the ROC curve of the 10-feature model was only marginally lower than that of the all-feature model, suggesting that the 10-feature model demonstrated a good net benefit and a high threshold probability, comparable to the all-feature model, indicating that both models have similar and high clinical utility. Given these findings, we selected the XGBoost model comprising 10 features: Month-old, FIB, Human IFN-γ, BAS, CRP, PCT, ESR, ALB, D-Dimer, and Human IL-10 as the final model. For the current task, this model exhibited outstanding performance, achieving an AUC of 0.9757, a sensitivity of 0.9385, a specificity of 0.9077, an accuracy of 0.9270, a precision of 0.9448, and a F1 score of 0.9416.

Model explanation

In the medical field, the interpretability of diagnosis is extremely important. ML-assisted diagnosis models must be interpretable. Ideally, it should be able to explain the complete logic of the corresponding decisions it provides to gain the trust of clinicians. Therefore, this study employed SHAP method to effectively achieve global and local explanations of the model by decomposing the prediction results into the individual contributions of each feature. The global explanation focuses on the overall importance of each feature in contributing to the model’s output. Specifically, as illustrated in the SHAP summary plots (Fig. 3a, b), we quantitatively assessed the overall contributions of each feature employing the mean SHAP values.

Global model explanation. (a) SHAP summary bar plot. This plot displays the ranking of feature importance based on Shapley values. (b) SHAP summary point plot. Each point represents a Shapley value for a specific patient and feature. Color of points represents actual feature values, where red represents higher values and blue represents lower values. The horizontal-axis displays the Shapley values, while the vertical-axis depicts features ordered by their mean absolute Shapley values. (c) SHAP dependence plot. Each individual subplot illustrating the impact of a single feature on the model’s prediction. Each point corresponds to a single patient, with SHAP values on the vertical-axis and actual feature values on the horizontal-axis.

Furthermore, to explore the specific impact of a single feature on the model’s decision, we conducted a further analysis of the SHAP dependence plots (Fig. 3c). This plot reveals the relationship between the actual values of these 10 features and their corresponding SHAP values. In this Figure, a feature’s SHAP value greater than zero signifies a positive impact to the model’s output, a higher probability of classifying a sample as a KD patient. Specifically, when a patient’s age in months (Month-old) ≤ 34.9, fibrinogen (FIB) ≥ 4.7 g/ml, human interferon-gamma (Human IFN-γ) ≤ 2.9pg/ml, basophil (BAS) ≥ 0.18 × 10^9/L, C-reactive protein (CRP) ≥ 32.49 mg/L, procalcitonin (PCT) ≥ 0.45ng/mL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) ≥ 43.0 mm/h, albumin (ALB) ≤ 37.6 g/L, D-dimer (D-Dimer) ≥ 0.18 mg/L, or human interleukin-10 (Human IL-10) ≥ 17.8pg/mL, the SHAP values for most of these features are greater than zero, the model tends to make a “KD diagnosis”.

Additionally, to explore the local interpretability of the model, we visualized the decision-making process for individual patients. Figure 4a, c show how a KD patient was predicted to be KD. As observed, the values of human interferon-γ (Human IFN-γ), ESR, PCT, ALB, D-Dimer, FIB, and CRP had a significant positive impact on the decision, meaning that these features push the decision towards the KD. Although BAS, Human IL-10, and Month-old had a certain negative impact, the overall score was 5.08, indicating that the probability of the patient having KD was 99.38%. Figure 4b, d show how an OD patient was correctly identified as OD. In the model’s decision-making process, FIB, ESR, and D-Dimer exerted a significant negative impact, which together pushed the model’s prediction towards the “OD”, ultimately outputting a result of −3.408, corresponding to a 2.8% probability that the patient has KD.

Local model explanation. (a,b) SHAP Waterfall plot. (c,d) SHAP Force plot. The plot a and c represent a patient with KD diagnosis to be predicted as KD, b and d represent a patient with OD diagnosis to be predicted as OD. The vertical-axis shows each feature and its actual value, and the horizontal-axis represent the Shapely Value. The arrows illustrate the influence of each feature on the model’s decision-making process, while the color represent whether the feature decreased (blue) or increased (red) the risk of KD. The combined effects of all features provided the final SHAP value \(\:f\left(x\right)\:\:\), which corresponded to the prediction score, serves as the baseline for SHAP, with its value being the mean of the model’s predicted score. The \(\:E\left[f\left(x\right)\right]\) serves as the baseline for shapely values, with its value being the mean of all the model’s prediction score.

Web application

To facilitate clinical application, the finally developed diagnostic model has been successfully incorporated into a web application based on the Streamlit framework, as illustrated in (Fig. 5). Streamlit, a powerful tool for building data applications, provides our web application with abundant interactive functionalities and intuitive visualization interfaces. When clinicians input the values of the 10 features required by the model, the application automatically utilizes these data to generate personalized risk assessments for KD in specific children. In addition to risk prediction, the program innovatively generates a waterfall plot for each child. This plot provides a clear and intuitive graphical display that highlights the features significantly influencing the diagnostic decision for KD.

Online KD-assisted diagnostic application. When the actual values of 10 features are input, application automatically output a 99.94% probability of KD. Concurrently, the waterfall plot illustrates the decision-making process: the red arrows toward right represent the features that incline the prediction towards KD, whereas the blue arrows toward left indicate the prediction towards OD.

Discussion

In our study, we comprehensively evaluated and compared the diagnostic performance of 10 distinct ML models for KD. Among these models, XGBoost demonstrated the optimal performance. By employing the SHAP method, we identified a series of clinical features that exhibit high efficacy in diagnosing KD. Based on these features, we successfully developed a diagnostic model using the XGBoost. Additionally, the implementation of the SHAP method significantly improved the model’s interpretability, allowing medical experts to understand it’s decision-making process more directly. To facilitate clinical application, we incorporated this model into a web application based on the Streamlit framework.

ML models have outstanding data processing and analysis capabilities, which can flexibly decipher complex relationships among variables in medical data and continuously improve model performance through training and optimization. In clinical applications, by combining easily-accessible, high-precision EMR data, ML-based assisted diagnosis models can significantly improve the accuracy and efficiency of medical diagnosis34,35. In our investigation into diagnosing KD, XGBoost emerged as the most superior ML model among those evaluated. This preference is supported by several reasons. Firstly, its gradient boosting decision tree architecture enables effective capture and management of the complex nonlinear relationships among clinical features of KD patients, a crucial capability given the disease’s intricate nature and manifestations36. Secondly, XGBoost incorporates advanced regularization techniques, which are vital for preventing overfitting, especially when dealing with limited medical data37. Thirdly, the model’s efficient execution and parallel processing capabilities allow for rapid handling of large datasets, making it ideal for real-time clinical applications where prompt decisions are essential38. Lastly, XGBoost is compatible with interpretability tools like SHAP, further enhancing its appeal in medical diagnosis and fostering a deeper understanding of the decision-making process39.

The decision to develop our final diagnostic model using XGBoost, incorporating 10 meticulously selected features, was informed by a thorough consideration of clinical relevance and model utility. These features are easily obtainable during routine patient assessments, positioning our model as a promising tool for the early diagnosis of KD. The simplicity and convenience of this ML diagnostic model are well-suited to the demand for efficient clinical decision-making34.

The absence of guidelines or consensus for feature selection in the diagnostic model makes the determination of the optimal number of features elusive. Incorporating more features may enrich the prediction model with additional information, but the inclusion of an excessive number of features may hinder clinical applicability, and non-causal features may compromise diagnostic accuracy40. To navigate this complexity, we employed the SHAP method for feature selection. SHAP provides a unified metric for assessing feature importance that is grounded in classic game theory principles, offering a more robust theoretical foundation compared to other methods. Moreover, SHAP values can be construed as the average marginal impact of each feature on the prediction outcome, thereby affording a transparent and intuitive insight into the model’s decision-making process. Finally, SHAP’s capability to manage complex models and account for nonlinear interactions among features renders it appropriate for our XGBoost model, which effectively captures the intricate patterns inherent in the clinical data of KD patients.

In the medical field, model interpretability is crucial for enhancing clinicians’ confidence in diagnostic results. However, ML models are frequently criticized for their “black box” nature, which leads to opacity and makes clinicians reluctant to use these models. This highlights a notable advantage of our study: we conducted a systematic interpretive analysis of the designed model by utilizing the SHAP method. Specifically, we observed that the model identified a lower month-old value as a significant diagnostic feature of KD, consistent with clinical observations indicating that KD primarily affects young children41,42. It is worth noting that our study discovered the key directional role of elevated ESR and CRP levels in the diagnosis of KD. Specifically, when a patient’s CRP level was ≥ 32.49 mg/L or ESR was ≥ 43.0 mm/h, the model tended to classify the patient as having KD. This finding was highly consistent with the diagnostic guidelines stated by the AHA43. Additionally, the high serum procalcitonin concentration was an important feature for the model to identify KD. Previous research has shown that PCT levels are significantly higher in KD patients than in those with autoimmune diseases and viral infections, validating PCT as a reliable and effective discriminatory feature for KD44. Conversely, a low serum albumin (ALB) concentration has also been identified as a notable marker for differentiating KD patients, primarily attributed to increased vascular permeability and ALB leakage during the acute phase of KD45,46. Notably, the AHA highlighted the crucial role of low ALB levels in the diagnosis of KD in its 2017 statement6. We also found that high levels of fibrinogen (FIB) have potential to serve as a diagnostic marker for KD. This finding is supported by previous research conducted by Yu et al., who analyzed proteomic differences between KD patients and other febrile patients, emphasizing the diagnostic relevance of fibrinogen in KD47. Furthermore, the model recognized elevated D-dimer levels as an effective diagnostic indicator, possibly attributed to vasculitis in KD patients leading to endothelial damage, subsequent coagulation system activation, and significantly increased D-dimer levels, as reported in previous studies2,48.

From the perspective of ML model, we identified several clinical features that are important for the diagnosis of KD. Our findings are highly consistent with current clinical practices and published research reports, verifying the robustness and reliability of the constructed models. Compared with traditional methods that have relied on a single diagnostic biomarker, our proposed final model exhibits superiority in diagnosing KD. This model was constructed based on 10 key clinical features, and is able to comprehensively considers and balances the interactions among these features. This advantage superiority enhances the diagnostic ability of the model and makes it outstanding in the accurate diagnosis of KD.

Considering that clinicians usually lack professional knowledge in ML and may find it challenging to directly apply ML models, we integrated the final diagnostic model and visualization analysis techniques into a web application using the Streamlit framework. Streamlit, as a powerful data application framework, facilitates the deployment and visualization of ML models in a straightforward manner. Based on this framework, we successfully transformed the KD diagnostic model into a user-friendly web application, enabling clinicians to easily operate and access it for precise diagnostic support without specialized ML background.

Nevertheless, our study still has some limitations. Given that the data we utilized was derived from a single-center database, a future objective is to collect additional data from different hospitals to validate the model’s generalizability. For clinical applications, a primary objective is to discriminate between mild and severe patients of KD, which is important for the subsequent treatment process. Mild patients require pharmacologic treatment, while severe patients often have complications associated with severe coronary artery lesions and need surgical intervention. Therefore, one of our future directions is to extend the model to the diagnosis of mild and severe KD.

Conclusion

In this study, we successfully developed an interpretable ML-assisted diagnostic model for KD in children. This model exhibits excellent performance, providing clinicians with intuitive decision-making support for diagnosis and offering new perspectives and tools for KD diagnosis. Our findings hold significant value and practical implications for advancing both the research and clinical practice of KD. This model is expected to enhance clinicians’ diagnostic accuracy and efficiency, thereby ultimately improving the patient’s diagnostic experience and treatment outcomes.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Zhejiang University Children’s Hospital, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with permission of Zhejiang University Children’s Hospital.

References

Kawasaki, T. Pediatric acute febrile mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome with characteristic desquamation of fingers and toes: my clinical observation of Fifty cases. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 21 (11), 1–38 (2002).

Newburger, J. W., Takahashi, M. & Burns, J. C. Kawasaki disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 67 (14), 1738–1749 (2016).

Jiang, S. et al. Predictive factors of medium-giant coronary artery aneurysms in Kawasaki disease. Pediatr. Res. 95 (1), 267–274 (2024).

Advani, N. et al. Long-term outcome of coronary artery dilatation in Kawasaki disease. Ann. Pediatr. Cardiol. 11 (2), 125–129 (2018).

Tutic, E. & Evey, K. Kawasaki disease: recent diagnostics, treatment, and predictors for treatment failure and coronary artery involvement. Curr. Emerg. Hosp. Med. Rep. 11 (4), 158–164 (2023).

Xu, D. et al. Progression prediction of coronary artery lesions by echocardiography-based ultrasomics analysis in Kawasaki disease. Ital. J. Pediatr. 50 (1), 185 (2024).

Fukazawa, R. et al. JCS/JSCS 2020 guideline on diagnosis and management of cardiovascular sequelae in Kawasaki disease. Circ. J. 84 (8), 1348–1407 (2020).

Mahajan, A. et al. Profile of children with Kawasaki disease associated with tropical infections. Indian J. Pediatr. 1–6. (2022).

Kuo, H. C. Diagnosis, progress, and treatment update of Kawasaki disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (18), 13948 (2023).

Wang, K. et al. Interpretable prediction of 3-year all-cause mortality in patients with heart failure caused by coronary heart disease based on machine learning and SHAP. Comput. Biol. Med. 137, 104813 (2021).

Tsai, C. M. et al. A novel score system of blood tests for differentiating Kawasaki disease from febrile children. PLoS One 16 (1), e0244721 (2021).

Ling, X. B. et al. Point-of-care differentiation of Kawasaki disease from other febrile illnesses. J. Pediatr. 162 (1), 183–188 (2013).

Hao, S. et al. A classification tool for differentiation of Kawasaki disease from other febrile illnesses. J. Pediatr. 176, 114–120 (2016).

Hao, S. et al. Multicentre validation of a computer-based tool for differentiation of acute Kawasaki disease from clinically similar febrile illnesses. Arch. Dis. Child. 105 (8), 772–777 (2020).

Li, C. et al. A machine learning model for distinguishing Kawasaki disease from sepsis. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 12553 (2023).

Tsai, C. M. et al. Use of machine learning to differentiate children with Kawasaki disease from other febrile children in a pediatric emergency department. JAMA Netw. Open 6 (4), e237489–e237489 (2023).

Lundberg, S. M. et al. Explainable machine-learning predictions for the prevention of hypoxaemia during surgery. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2 (10), 749–760 (2018).

Cabitza, F., Rasoini, R. & Gensini, G. F. Unintended consequences of machine learning in medicine. Jama 318 (6), 517–518 (2017).

Chen, T., Guestrin, C. & Xgboost A scalable tree boosting system. Proceedings of the 22nd acm sigkdd international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining 785–794. (2016).

Friedman, J. H. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 1189–1232. (2001).

Uddin, S. et al. Comparative performance analysis of K-nearest neighbour (KNN) algorithm and its different variants for disease prediction. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 6256 (2022).

Joung, J. et al. A decision tree model for predicting intravenous Immunoglobulin resistance and coronary artery involvement in Kawasaki disease. BMC Pediatr. 22 (1), 474 (2022).

Chen, H. et al. Establishment and analysis of a disease risk prediction model for the systemic lupus erythematosus with random forest. Front. Immunol. 13, 1025688 (2022).

Cortes, C. & Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 20, 273–297 (1995).

Zhang, M. et al. Risk factors and an early predictive model for Kawasaki disease shock syndrome in Chinese children. Ital. J. Pediatr. 50 (1), 22 (2024).

Prokhorenkova, L. et al. CatBoost: unbiased boosting with categorical features. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 31. (2018).

Ying, C. et al. Advance and prospects of adaboost algorithm. Acta Automat. Sin. 39 (6), 745–758 (2013).

Lin, H. et al. Machine Learning and human-machine Trust in Healthcare: A Systematic Survey (CAAI Transactions on Intelligence Technology, 2023).

Alicioglu, G. & Sun, B. A survey of visual analytics for explainable artificial intelligence methods. Comput. Graph. 102, 502–520 (2022).

Hu, C. et al. Application of interpretable machine learning for early prediction of prognosis in acute kidney injury. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 20, 2861–2870 (2022).

Yagin, F. H. et al. Explainable artificial intelligence model for identifying COVID,19 gene biomarkers. Comput. Biol. Med. 154, 106619 (2023).

Charlton, C. E. et al. Development of prediction models for one-year brain tumour survival using machine learning: a comparison of accuracy and interpretability. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 233, 107482 (2023).

Das, S. et al. XAI–reduct: accuracy preservation despite dimensionality reduction for heart disease classification using explainable AI. J. Supercomput. 79 (16), 18167–18197 (2023).

Xu, J. et al. Identification and validation of an explainable prediction model of acute kidney injury with prognostic implications in critically ill children: a prospective multicenter cohort study. EClinicalMedicine, 68. (2024).

Goecks, J. et al. How machine learning will transform biomedicine. Cell 181 (1), 92–101 (2020).

Farzipour, A., Elmi, R. & Nasiri, H. Detection of Monkeypox cases based on symptoms using XGBoost and Shapley additive explanations methods. Diagnostics 13 (14), 2391 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Predicting missing values in medical data via XGBoost regression. J. Healthc. Inf. Res. 4, 383–394 (2020).

Budholiya, K., Shrivastava, S. K. & Sharma, V. An optimized XGBoost based diagnostic system for effective prediction of heart disease. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inform. Sci. 34 (7), 4514–4523 (2022).

Abbas, Z. et al. XGBoost framework with feature selection for the prediction of RNA N5-methylcytosine sites. Mol. Ther. 31 (8), 2543–2551 (2023).

Fan, F. et al. Development and validation of a multimodal deep learning framework for vascular cognitive impairment diagnosis. Iscience 27 (10). (2024).

Rowley, A. H. & Shulman, S. T. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of Kawasaki disease. Front. Pead. 6, 374 (2018).

Lin, M. T. & Wu, M. H. The global epidemiology of Kawasaki disease: review and future perspectives. Global Cardiol. Sci. Pract. 2017 (3). (2017).

Newburger, J. W. et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a statement for health professionals from the committee on rheumatic fever, endocarditis and Kawasaki disease, Council on cardiovascular disease in the young, American heart association. Circulation 110 (17), 2747–2771 (2004).

Okada, Y. et al. Serum procalcitonin concentration in patients with Kawasaki disease. J. Infect. 48 (2), 199–205 (2004).

Xia, Y. et al. Albumin level and progression of coronary artery lesions in Kawasaki disease: A retrospective cohort study. Front. Pead. 10, 947059 (2022).

Terai, M. et al. Prognostic impact of vascular leakage in acute Kawasaki disease. Circulation 108 (3), 325–330 (2003).

Yu, H. R. et al. A unique plasma proteomic profiling with imbalanced fibrinogen cascade in patients with Kawasaki disease. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 20 (7), 699–707 (2009).

Imamura, T. et al. Impact of increased D-dimer concentrations in Kawasaki disease. Eur. J. Pediatr. 164, 526–527 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We pay sincere thanks to all experts who participated in this study. We also would like to thank to all cited researchers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MD, ZG, and GQ conceived and designed the study. ZL and LC participated in the literature search. GQ and ZG performed the data curation and preparation. GY, YZ, and PK prepared the experimental equipment and resources. MD performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. FG validated the results and evaluated the findings. All authors approved the final manuscript for submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Children’s Hospital (Approval Letter of IRB/EC, 2024-IRB-0009-P-01) and waived the need for informed consent from patients, as long as the data of the patient remained anonymous. All of the methods were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Duan, M., Geng, Z., Gao, L. et al. An interpretable machine learning-assisted diagnostic model for Kawasaki disease in children. Sci Rep 15, 7927 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92277-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92277-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Kawasaki disease in India: emerging burden and future challenges

Proceedings of the Indian National Science Academy (2025)

-

Kawasaki Disease: Unraveling Immunopathogenesis, Genetic Factors, and AI Applications in Diagnosis with a Focus on Iran

Pediatric Cardiology (2025)