Abstract

Sepsis-associated acute kidney injury (SA-AKI) is a severe complication in critically ill patients, with a complex pathogenesis involving in cell cycle arrest, microcirculatory dysfunction, and inflammation. Current diagnostic strategies remain suboptimal. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate pathophysiology-based biomarkers and develop an improved predictive model for SA-AKI. The prospective observational study was conducted, enrolling 26 healthy individuals and 96 sepsis patients from Peking University Third Hospital. Clinical and laboratory data were collected, and patients were monitored for AKI development within 72 h. Further, sepsis patients were categorized into SA-noAKI (n = 46) and SA-AKI (n = 50) groups. Novel biomarkers, including tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 (TIMP-2), insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-7 (IGFBP-7), and angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2), were measured in all participants. Among these sepsis patients, the SA-AKI incidence was 52.08% (50/96). Compared to SA-noAKI, the SA-AKI group had significantly higher levels of TIMP-2 (93.55 [79.36, 119.56] ng/mL), IGFBP-7 (27.8 [21.44, 37.29] ng/mL), TIMP-2×IGFBP-7 (2.91 [1.90, 3.55] (ng/mL)²/1000), and Ang-2 (10.61 [5.79, 14.57] ng/mL) (P < 0.05). Accordingly, logistic regression identified TIMP-2×IGFBP-7 (OR = 2.71), Ang-2 (OR = 1.19), and PCT (OR = 1.05) as independent risk factors. The ROC curve of the predictive model demonstrated superior early-stage accuracy (AUC = 0.898), which remained stable during internal validation (AUC = 0.899). Meanwhile, the nomogram exhibited that this model was characterized with excellent discrimination, calibration, and clinical performance. In general, TIMP-2×IGFBP-7, Ang-2 and PCT were the independent risk factors for SA-AKI, and the novel model based on the three indicators provided a more accurate and sensitive strategy for the early prediction of SA-AKI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sepsis is a life-threatening clinical syndrome that often results in kidney dysfunction, referred to as sepsis-associated acute kidney injury (SA-AKI)1. This complex and heterogeneous condition can arise either directly from the pathophysiological effects of sepsis or indirectly due to complications associated with its treatment2. The incidence of SA-AKI is reported to range from 45–70%3. Compared to patients with acute kidney injury (AKI) from other causes, those with SA-AKI typically present with more severe illness and significantly higher mortality rates4,5. early recognition is crucial for improving the prognosis of SA-AKI. However, current diagnostic criteria for SA-AKI, which rely on serum creatinine (Scr) levels or urine output, have notable limitations. On the one hand, changes in Scr levels are often delayed due to the kidney’s compensatory mechanisms and are influenced by factors such as muscle mass, age, sex, ethnicity, and extreme dietary habits. Moreover, baseline Scr levels are frequently unavailable for many patients, complicating diagnosis1. On the other hand, urine output measurements are difficult to obtain accurately in routine clinical practice, further hindering timely diagnosis6. Therefore, it is urgent for more effective and advanced biomarkers to predict the development of SA-AKI.

Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 (TIMP-2) and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 (IGFBP-7) are widely recognized as novel stress biomarkers for AKI, primarily involved in its pathogenesis through the induction of cell cycle arrest7. Extensive clinical studies have demonstrated that the combined detection of TIMP-2 and IGFBP-7 (TIMP-2×IGFBP-7) serves as a robust tool for the early prediction of AKI, as these biomarkers exhibit changes earlier than Scr levels8,9. Moreover, they hold significant value in risk stratification and prognosis assessment for AKI10,11. Despite these promising prospects, their clinical application in SA-AKI remains limited.

Angiopoeitin-2 (Ang-2), as the biomarker of endothelial injury, plays an important role in microvascular dysfunction, which is widely used in evaluating the diagnosis, severity, and prognosis of sepsis12. Accumulating evidence suggests that endothelial activation is essential for SA-AKI progression13, indicating that Ang-2 may be a reliable biomarker for the detection of SA-AKI. Nevertheless, the clinical significance of endothelial markers in reflecting SA-AKI pathophysiology has not been clarified.

Given the intricate pathophysiological interplay between sepsis and AKI, a single biomarker is often insufficient to capture the full complexity of SA-AKI. In 2023, the consensus report from the 28th Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI) Workgroup highlighted the importance of integrating clinical information with SA-AKI biomarkers to provide more actionable insights for guiding patient care and treatment strategies2. The report further proposed a reclassification of biomarkers for AKI and sepsis. Biomarkers for kidney injury were categorized into functional markers (e.g., serum creatinine), damage markers (e.g., kidney injury molecule-1), and stress markers (e.g., TIMP-2, IGFBP-7), while biomarkers for sepsis were primarily grouped into markers reflecting inflammation and endothelial dysfunction2. Based on this consensus, our study combines clinical data with SA-AKI biomarkers including TIMP-2, IGFBP-7, and Ang-2 to enable a comprehensive evaluation of SA-AKI. This integrative approach aims to improve early prediction and risk stratification, ultimately improving clinical outcomes.

Methods

Study population

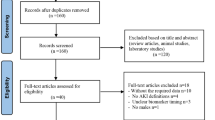

This prospective observational study was conducted in Peking University Third Hospital Emergency Department in China. Before inclusion in this study, initial evaluation was performed on all patients with suspected sepsis who were admitted to the emergency department. The research team collected laboratory test data, clinical symptoms, past medical history, and a thorough medical history from patients who satisfied the inclusion criteria but did not satisfy the exclusion criteria. 120 patients were enrolled from April 2017 to November 2021 according to the sepsis-3 criteria. Further, 96 patients with sepsis were finally included and 24 patients were excluded according to the exclusion criteria. Meanwhile, 26 age-, sex- and ethnicity-matched healthy donors were selected as health group. These patients with sepsis were closely monitored within 72 h after admission and subsequently classified into two groups according to the AKI criteria (Fig. 1), including sepsis-associated-no AKI group (SA-noAKI, n = 46) and sepsis-associated-AKI group (SA-AKI, n = 50). This study involving human participants were approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University Third Hospital (M2017032). The principle of the Helsinki Declaration for using human subjects was obeyed. All subjects gave their informed consent to participate in this study for diagnostic and research purposes.

Inclusion criteria

-

(1)

Emergency patients age≥18

-

(2)

Fulfill the diagnostic criteria of sepsis-3

Exclusion criteria

-

(1)

Estimated hospitalization time <48h

-

(2)

Pre-existing chronic kidney disease

-

(3)

Patients with confirmed AKI for the first time of sample collection

-

(4)

Patients who have received kidney transplantation

-

(5)

Patients who have undergone hemodialysis or are in urgent need of hemodialysis upon admission

-

(6)

Received drug treatment (including corticosteroids, immunomodulators, or antibiotics, and contrast agents) in the preceding two weeks

-

(7)

Known infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or a hepatitis virus

Definition of SA-AKI

Sepsis and septic shock were defined according to the Third International Consensus14: the presence of a known or suspect bacterial infection; an acute change in the sepsis-related organ failure assessment (SOFA) score ≥ 2 points. The AKI was defined based on the improved global prognosis of nephropathy (KDIGO) criteria15: increasing in Scr of 0.3 mg/dL within 48 h; an elevation to 1.5-fold of the baseline level within the first 7 days; or a decline in urine output to not exceeding 0.5 mL/kg per hour for at least 6 h. Determining SA-AKI within 72 h after admission. The baseline creatinine was referred to previous research9,15,16: if three values were at least available, the median of all available values from three months to seven days prior to enrollment was used; if pre-enrollment creatinine was not available, the creatinine value at the time of enrollment was used. Baseline kidney function was evaluated using the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), derived from the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation.

Collecting clinical data

Based on the clinical expertise of emergency medicine specialists and previous studies, comprehensively collect clinical information related to SA-AKI. Clinical data and traditional tests at admission were obtained from the hospital’s electronic system, including age, gender, co-morbidities, initial vital signs, the source of infection site, and the laboratory examination results. The acute physiology and chronic health assessment (APACHE) II score and sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score were calculated to assess the SA-AKI severity on the first day of admission. The white blood cell (WBC) count, neutrophils (Neut), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin (PCT) were analyzed to evaluate inflammation. D-dimer (D-D), Fibrin degradation products (FDP), and fibrinogen (Fib) were utilized for estimating the coagulation function. Meanwhile, observing kidney function indicators every 24 h for the first 3 days, mainly including urea (BUN), serum uric acid (SUA), and serum creatinine (Scr).

ELISA assay

Venous blood samples were collected by trained medical professionals within 24 h of sepsis diagnosis and admission to the emergency department. The collection, transport, and storage of specimens were conducted in accordance with the industry-standard protocol for blood specimen collection and handling for clinical chemistry testing (WS/T 225–2024). The blood samples were centrifuged at 3,500 rpm for 10 min to obtain serum, which were then stored at -80 °C for subsequent analysis. Serum concentrations of TIMP-2, IGFBP-7, and Ang-2 were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits, following the manufacturer’s instructions and performed by experienced laboratory personnel. The TIMP-2 and IGFBP-7 concentrations were multiplied to calculate the TIMP-2×IGFBP-7 product, which was then divided by 1,000. The TIMP-2 ELISA kit (DTM200) and Ang-2 ELISA kit (DANG20) were purchased from R&D Systems, while the IGFBP-7 ELISA kit (ab213790) was obtained from Abcam. During the entire testing process, laboratory operators were blinded to the clinical information of the patients.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 26.0 or R version 4.0.3. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of data distribution. Descriptive statistics were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range, 25–75%). Comparisons between two groups were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test or two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test for continuous variables, and the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Missing data, which accounted for less than 5% of the dataset, were handled using mean imputation. Collinearity analysis was conducted to avoid multicollinearity among covariates. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to develop the prediction model for SA-AKI. The model’s performance was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, with DeLong’s test applied to compare AUC values. The Youden index was used to determine the optimal cutoff value, sensitivity, and specificity. After establishing a nomogram, Hosmer–Lemeshow test and decision curve analysis (DCA) were utilized for evaluating its Goodness of fit and clinical utility, respectively. To further validate the model’s accuracy and stability, subgroup analysis, trend analysis, and bootstrap resampling were conducted.

Results

Clinical and laboratory characteristics

Baseline demographic and clinical features of the health and sepsis groups were presented in Supplementary Table S1. 26 healthy donors aged from 66 to75 years old, 62% were male, and 96 patients with sepsis aged from 62 to 84 years old, 58% were male. The age and gender between two groups showed no differences.

Further, we concluded the clinical and laboratory characteristics of 96 patients with sepsis (Table 1). 52.08% (50/96) of patients with sepsis developed into AKI in the first 72 h according to the 2012 KDIGO definition, defined as SA-AKI group. Compared to the SA-noAKI group, patients with SA-AKI had worse disease states, and their SOFA score, the frequency of vasopressor use, and the proportion of septic shock were significantly elevated (P < 0.05). In line with these, the levels of NLR, CRP, PCT, BUN, SUA, D-D, and FDP in patients with SA-AKI were significantly increased compared to the SA-noAKI group (P < 0.05), indicating more serious inflammation response, worse renal dysfunction, and severer coagulation system disorder.

Flowchart exhibiting the selection of the patients. 120 sepsis patients were admitted, 96 of whom were remained due to the inclusion principle. Patients with sepsis were further divided into SA-noAKI group (n = 46) and SA-AKI group (n = 50) according to the AKI criteria. At the same period, 26 healthy donors were selected as health group.

Elevated biomarkers in patients with SA-AKI

TIMP-2 and IGFBP-7 are identified as effective biomarkers for cell cycle arrest during the progression of AKI. Ang-2 has a great contribution to microvascular dysfunction in sepsis. To further clarifying the correlation of TIMP-2, IGFBP-7 and Ang-2 in patients with SA-AKI, we detected the concentrations of serum TIMP-2, IGFBP-7, TIMP-2×IGFBP-7, and Ang-2 in the health, SA-noAKI, and SA-AKI groups. The concentrations of TIMP-2 (93.55[79.36, 119.56]ng/mL), IGFBP-7 (27.8[21.44, 37.29]ng/mL), TIMP-2×IGFBP-7 (2.91[1.90, 3.55] (ng/mL)2/1000) and Ang-2 (10.61[5.79, 14.57]ng/mL) were the highest in the SA-AKI group, followed by the SA-noAKI group (Fig. 2). Only the comparison of TIMP-2 between the health (69.52 [58.85, 75.66]) ng/mL) and the SA-noAKI (70.94[56.61,86.28] ng/mL) group had no statistical difference (P > 0.05). In addition, the trend test results showed that the incidence of SA-AKI was significantly higher in the high-level groups of PCT, TIMP-2×IGFBP-7, and Ang-2 compared to the low-level groups (Supplementary Table S3).

Risk indicators for patients with SA-AKI

Next, we analyzed the clinical and laboratory parameters in the SA-AKI and the SA-noAKI groups using univariate logistic regression analysis. To avoid overfitting, a collinearity analysis was performed on the selected variables (Supplementary Table S4). These findings indicated that SOFA (OR = 1.14 [1.01–1.29]), PCT (OR = 1.03 [1.00-1.06]) and SUA (OR = 1.01 [1.00-1.01]) were the significant risk indicators of SA-AKI. Then, novel biomarkers TIMP-2, IGFBP-7, TIMP-2×IGFBP-7, and Ang-2 were added and analyzed using multivariate logistic regression analysis. The results showed that TIMP-2×IGFBP-7 (OR = 2.71 [1.52–4.84]), Ang-2 (OR = 1.19 [1.06–1.33]), PCT (OR = 1.05 [1.01–1.09]) were the independent risk factors for SA-AKI (Table 2).

A novel model for early predicting SA-AKI

Further, this study constructed the prediction model for SA-AKI based on the independent risk factors. Model 1 was performed via analyzing SOFA, PCT and SUA, and its AUC value was 0.797 (sensitivity 76%, specificity 76.1%). Model 2 were established based on TIMP-2×IGFBP-7, Ang-2 and PCT, and its discriminatory capacity (AUC 0.898, sensitivity 82%, specificity 91.3%) was significantly higher than that of Model 1 (P = 0.035), indicating a more accurate prediction for SA-AKI (Fig. 3). Considering that factors such as age, severity of sepsis, and the presence of malignancies may influence the occurrence of SA-AKI, the model was evaluated across different subgroups (Supplementary Table S5). The results showed that the model performed well in all subgroups. Furthermore, internal validation using bootstrap resampling confirmed the model’s robust predictive performance for the early detection of SA-AKI (Supplementary Figure S6).

The nomogram and calibration of the novel model for SA-AKI

To more comprehensively display the performance of model 2 for SA-AKI prediction, a nomogram with TIMP-2×IGFBP-7, Ang-2, PCT was constructed (Fig. 4a). Matching points of every parameter in the nomogram would be added up to obtain a total score, facilitating the evaluation of the risk of SA-AKI. And the Hosmer–Lemeshow test’s p-value of this model was 0.273, indicating a satisfactory goodness-of-fit. The calibration curve was demonstrated in Fig. 4b, implying that the new model has a good predictive performance for SA-AKI.

(a) The nomogram of the novel prediction model for SA-AKI. (b)The calibration curves for the nomogram of the model. The solid line represented the performance of the nomogram. The diagonal dotted line represented a perfect prediction using an ideal model. The closer the solid line fits to the dotted line, the better predictive ability of the nomogram has. TIMP-2 tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2, IGFBP-7 insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7, Ang-2 angiopoietin-2, PCT procalcitonin.

The clinical value of the prediction model for SA-AKI

To further assess the clinical utility of this novel model, a decision curve analysis (DCA) was conducted based on the established predictive nomogram (Fig. 5). Within a threshold probability range of 0.18 to 0.90, the DCA curve for Model 2 demonstrated superior net benefits compared to Model 1, indicating its greater clinical applicability across a wide range of decision-making scenarios. Specifically, when the predicted risk of SA-AKI reaches or exceeds 18%, clinicians may consider implementing interventions such as closer monitoring, prophylactic treatment, or other management strategies. When the predicted risk reaches or exceeds 90%, clinicians are highly likely to initiate immediate and intensive therapeutic interventions. Therefore, the decision curve analysis serves as a valuable tool to aid clinicians in optimizing the management of high-risk patients.

Discussion

SA-AKI has emerged as one of the leading causes of mortality in emergency department patients. However, traditional diagnostic criteria based on renal function markers Scr and urine output are hindered by their delayed response and inherent variability. These limitations pose significant challenges to the timely identification and management of SA-AKI. To address these challenges, researchers have been exploring various strategies for early detection. This study, grounded in the latest consensus from the ADQI, aimed to integrate clinical information and biomarkers of SA-AKI to identify key risk factors and construct a predictive model to support early recognition and clinical decision-making. In this study, we incorporated novel kidney stress biomarkers TIMP-2 and IGFBP-7, as well as the sepsis biomarker Ang-2. The results demonstrated that a model including TIMP-2×IGFBP-7, Ang-2, and PCT outperformed models relying solely on conventional metrics. Notably, the three biomarkers in the model each reflect distinct core pathophysiological mechanisms of SA-AKI: TIMP-2×IGFBP-7 indicates G1 cell cycle arrest, Ang-2 reflects microcirculatory dysfunction, and PCT captures the systemic inflammatory state. These mechanisms are widely recognized as pivotal in the development of SA-AKI. Therefore, a combination of biomarkers based on the key pathophysiological mechanisms of SA-AKI can more accurately predict the occurrence of SA-AKI. Furthermore, the integration of these biomarkers highlights the multifactorial and multimodal nature of SA-AKI pathophysiology, providing a solid theoretical foundation for early diagnosis, risk stratification, and therapeutic intervention.

SA-AKI is characterized by systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and dysregulated immune responses, accompanied by a severe cytokine storm and coagulopathy. Inflammation promotes coagulation on the one hand, while coagulation products further amplify the inflammatory response on the other, forming a positive feedback loop that drives the progression of SA-AKI17. These complex pathophysiological mechanisms contribute to the worse prognosis of SA-AKI compared to other types of AKI. Our findings also revealed that patients with SA-AKI had significantly higher SOFA scores, an increased frequency of vasopressor use, and a higher incidence of septic shock. Furthermore, compared to the SA-noAKI group, SA-AKI patients exhibited more severe inflammatory responses, greater kidney dysfunction, and more pronounced coagulopathy. This was evidenced by significantly elevated levels of NLR, CRP, PCT, BUN, SUA, D-D, and FDP. These results suggest that the interplay between inflammation and coagulopathy plays a pivotal role in the development and progression of SA-AKI. Furthermore, the combined detection of these biomarkers holds great potential for identifying high-risk populations of SA-AKI. For instance, one study reported that a predictive model incorporating vasopressor use, patient age, PCT, and D-D levels accurately and reliably identified high-risk individuals for SA-AKI, with an AUC of 0.832. In addition, this model demonstrated clinical utility in predicting 30-day survival rates and the occurrence of major adverse kidney events (MAKE) within 30 days18. Among these biomarkers, PCT is a well-established indicator of inflammation, released into the bloodstream in response to bacterial infection19. It has been widely used as a biomarker for bacterial infections and is considered a promising diagnostic marker for sepsis20. Previous studies have confirmed that PCT outperforms CRP, IL-6, and NLR in identifying SA-AKI21,22. Consistent with these findings, our data demonstrated that PCT was more specific for SA-AKI than other inflammatory markers. Therefore, targeting coagulation and inflammation may represent a promising direction for the diagnosis and treatment of SA-AKI.

TIMP-2 and IGFBP-7, as cell cycle arrest proteins, are primarily secreted and expressed by renal tubular cells and reflect the pre-injury cellular state in acute kidney injury (AKI). When the kidney sustains damage from various stressors, the expression of TIMP-2 and IGFBP-7 is upregulated. Specifically, IGFBP-7 increases the expression of p53/p21, while TIMP-2 enhances p27 expression. These proteins, through autocrine and paracrine mechanisms, bind to their respective receptors and inhibit cyclin-dependent kinase complexes, causing cells to arrest in the G1 phase, facilitating DNA repair9. However, prolonged cell cycle arrest can contribute to cellular dysfunction. In addition to their roles in cell cycle regulation, both TIMP-2 and IGFBP-7 play crucial roles in inflammation and apoptosis. TIMP-2 promotes p65 phosphorylation, activating nuclear factor NF-κB, which induces the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and triggers apoptosis23,24. Similarly, IGFBP-7 activates ERK1/2 signaling, driving epithelial-mesenchymal transition and apoptosis in tubular epithelial cells in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation25,26. Previous studies have demonstrated that TIMP-2 and IGFBP-7 are capable of predicting the early onset of AKI. Notably, the product of these two biomarkers (TIMP-2×IGFBP-7) has shown superior predictive performance for AKI development compared to individual biomarkers and outperforms other markers such as neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), cystatin C, kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1), IL-18, glutathione S-transferase, and liver-type fatty acid-binding protein9. Moreover, TIMP-2×IGFBP-7 also offers advantages in assessing disease progression and prognosis. Studies have shown that these biomarkers can effectively identify high-risk patients likely to progress from mild or moderate to severe AKI during septic shock, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.8327. Continuous monitoring of TIMP-2×IGFBP-7 has shown promising predictive performance. Specifically, a decline in TIMP-2×IGFBP-7 levels is associated with a reduced risk of adverse clinical outcomes, whereas persistently elevated levels correlate with increased mortality, dialysis dependency, and other adverse events11. Importantly, the 23rd ADQI Consensus Conference recommended integrating TIMP-2×IGFBP-7 into the new AKI staging framework, facilitating better patient prognosis assessment10. The clinical utility of TIMP-2×IGFBP-7 has been further validated, with elevated levels prompting more frequent nephrology consultations. Early nephrology consultations, in turn, have been shown to improve patient outcomes28. In our study, we observed that TIMP-2 and IGFBP-7 were synergistically upregulated in SA-AKI, and TIMP-2×IGFBP-7 emerged as an independent risk factor for SA-AKI, highlighting its potential for early prediction and intervention in SA-AKI. However, despite its promising potential, the clinical use of TIMP-2 × IGFBP-7 in the management of SA-AKI remains limited and warrants further investigation.

Ang-2-mediated microcirculatory dysfunction is a well-established pathological mechanism contributing to the progression of both SA-AKI29 and sepsis30. By binding to the TIE-2 receptor, Ang-2 inhibits the protective signaling pathway of Ang-1, leading to disruption of endothelial cell junctions, increased vascular permeability, and subsequent microcirculatory dysfunction31. These changes result in renal microvascular thrombosis, reduced renal blood flow, and ultimately, the progression of SA-AKI. Consequently, Ang-2 functions as both a risk factor and a biomarker for SA-AKI. In this study, we demonstrated that Ang-2 is a valuable indicator for the early prediction of SA-AKI, as its levels increase during disease progression. However, Ang-2 alone lacks sufficient specificity for SA-AKI, necessitating its combination with other biomarkers for more accurate.

In summary, our study demonstrated that TIMP-2×IGFBP-7, Ang-2, and PCT are synergistically upregulated in SA-AKI, with their combined assessment exhibiting enhanced sensitivity and specificity. This finding supports the development of novel predictive models for the early detection of SA-AKI and provides a foundation for clinical application. These biomarkers were measured using the ELISA method, which is simple, practical, and suitable for various clinical settings, facilitating integration into routine clinical practice. Furthermore, the primary samples required for detecting these biomarkers are blood and urine, which are readily accessible and minimally invasive for patients. Therefore, predictive models incorporating these biomarkers could enable the timely identification of SA-AKI, allowing for early intervention in nephrotoxic drug administration and fluid management, ultimately reducing the incidence and severity of AKI. However, our study had several limitations: Firstly, AKI was just determined by Scr, but the concentration of Scr was not be accurately measured due to the inaccurate urine volume records in emergency patients as well as the susceptibility to liquid capacity, drugs, and nutritional status. Secondly, the level of biomarkers was only detected for the first time at admission, lacking of a dynamical monitoring. Thereby, the relationship between the concentrations of novel biomarkers and the stage and severity of SA-AKI cannot be verified. Finally, this study was a single-center study with a small sample size in emergency department, only representing a small part of older patients with sepsis who had many basic diseases and lacking of an external validation. Thus, the clinical performance of the combination biomarkers needs to be proven in more population.

Conclusions

In conclusion, TIMP-2×IGFBP-7, Ang-2 and PCT were identified to be the independent risk factors for SA-AKI, and the novel model based on the three indicators offered a solid support for the accurate and sensitive prediction of SA-AKI in the early stages.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, [Liyan Cui], upon reasonable request.

References

Poston J T, Koyner J L. Sepsis associated acute kidney injury. BMJ (Clinical Res. ed). 364, k4891 (2019).

ZARBOCK, A. et al. Sepsis-associated acute kidney injury: consensus report of the 28th acute disease quality initiative workgroup. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 19 (6), 401–417 (2023).

Hoste E A, Bagshaw S M, Bellomo R. et al. Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: the multinational AKI-EPI study. Intensive Care Med. 41 (8), 1411–1423 (2015).

Legrand, M. et al. Sepsis-associated acute kidney injury: recent advances in enrichment strategies, sub-phenotyping and clinical trials. (2024). Critical care (London, England), 28(1): 92 .

White K C, Serpa-neto A, Hurford R. et al. Sepsis-associated acute kidney injury in the intensive care unit: incidence, patient characteristics, timing, trajectory, treatment, and associated outcomes. A multicenter, observational study. Intensive Care Med. 49 (9), 1079–1089 (2023).

Kasugai D, Nakashima T, Goto T. Clinical implications of urine output-based sepsis-associated acute kidney injury. Intensive Care Med. 49 (10), 1263–1265 (2023).

Stanski N L, Rodrigues C E, Strader M. et al. Precision management of acute kidney injury in the intensive care unit: current state of the Art. Intensive Care Med. 49 (9), 1049–1061 (2023).

Palmowski, L. et al. Predictive enrichment for the need of renal replacement in sepsis-associated acute kidney injury: combination of Furosemide stress test and urinary biomarkers TIMP-2 and IGFBP-7. Ann. Intensiv. Care. 14 (1), 111 (2024).

Kashani, K. et al. Discovery and validation of cell cycle arrest biomarkers in human acute kidney injury. (2013). Critical care (London, England), 17(1): R25 .

Molinari, L. et al. Utility of biomarkers for sepsis-associated acute kidney injury staging . JAMA Netw. Open. 5 (5), e2212709 (2022).

Fioentino, M. et al. Serial measurement of cell-cycle arrest biomarkers [TIMP-2] · [IGFBP7] and risk for progression to death, dialysis, or severe acute kidney injury in patients with septic shock. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 202 (9), 1262–1270 (2020).

Rosenbergr C, M. et al. Early plasma angiopoietin-2 is prognostic for ARDS and mortality among critically ill patients with sepsis. (2023). Critical care (London, England), 27(1): 234 .

Girardis, M. & Ferrer, D. A. V. I. D. S. Understanding, assessing and treating immune, endothelial and haemostasis dysfunctions in bacterial sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 50 (10), 1580–1592 (2024).

Singer, M. et al. The third international consensus definitions for Sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). Jama 315 (8), 801–810 (2016).

Palevsky, P. M. et al. KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 61 (5), 649–672 (2013).

Nussang, C. et al. Cell cycle biomarkers and soluble Urokinase-Type plasminogen activator receptor for the prediction of Sepsis-Induced acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy: A prospective, exploratory study. Crit. Care Med. 47 (12), e999–e1007 (2019).

Hua, T. et al. Megakaryocyte in sepsis: the trinity of coagulation, inflammation and immunity. (2024). Critical care (London, England), 28(1): 442 .

Lin, C. et al. Development and validation of an early acute kidney injury risk prediction model for patients with sepsis in emergency departments. Ren. Fail. 46 (2), 2419523 (2024).

Karzai, W. et al. Procalcitonin–a new indicator of the systemic response to severe infections. Infection 25 (6), 329–334 (1997).

Wacker, C. et al. Procalcitonin as a diagnostic marker for sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 13 (5), 426–435 (2013).

FU, G. et al. Association between procalcitonin and acute kidney injury in patients with bacterial septic shock. Blood Purif. 50 (6), 790–799 (2021).

Zhou, X. et al. [Predictive value of inflammatory markers for acute kidney injury in sepsis patients: analysis of 753 cases in 7 years]. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 30 (4), 346–350 (2018).

Li, Y. M. et al. Downregulation of TIMP2 attenuates sepsis-induced AKI through the NF-κb pathway. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Disease. 1865 (3), 558–569 (2019).

Jiang, N. et al. TIMP2 mediates endoplasmic reticulum stress contributing to sepsis-induced acute kidney injury. FASEB Journal: Official Publication Federation Am. Soc. Experimental Biology. 36 (4), e22228 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. IGFBP7 regulates sepsis-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition through ERK1/2 signaling. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 51 (8), 799–806 (2019).

Verhagen H J et al. IGFBP7 induces apoptosis of acute myeloid leukemia cells and synergizes with chemotherapy in suppression of leukemia cell survival. Cell Death Dis. 5 (6), e1300 (2014).

Maizel, J. et al. Urinary TIMP2 and IGFBP7 identifies high risk patients of short-term progression from mild and moderate to severe acute kidney injury during septic shock: a prospective cohort study. disease markers, 2019: 3471215. (2019).

LA A M, Gunning, S. et al. Real-world use of AKI biomarkers: a quality improvement project using urinary tissue inhibitor metalloprotease-2 and insulin-like growth factor binding protein 7 ([TIMP-2]*[IGFBP7]). Am. J. nephrol., 54 (7–8): 281 – 90. (2023).

Van Meurs, M. et al. Bench-to-bedside review: angiopoietin signalling in critical illness - a future target?. Crit. Care. 13 (2), 207 (2009).

Zhuo, M. et al. Angiopoietin-2 as a prognostic biomarker in septic adult patients: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Intensiv. Care. 14 (1), 169 (2024).

Parikh, S. M. et al. Excess Circulating angiopoietin-2 May contribute to pulmonary vascular leak in sepsis in humans. PLoS Med. 3 (3), e46 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants for their contribution to the present study.

Funding

The study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (61771022, 62071011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributions conceptualization: ZQ, CLY. Data curation: ZQ, YBX, LXD, ZY, YS, MQB, CLY. Formal analysis: ZQ, YBX, ZY, YS. Funding acquisition: CLY. Investigation: ZQ, MQB, CLY. Methodology: ZQ, YBX, ZY, LXD, CLY. Supervision: CLY. Writing – original draft: ZQ. Writing – review & editing: ZQ, CLY.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

The study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University Third Hospital (M2017032).

Approval for human experiments

All subjects gave their informed consent to participate in this study for diagnostic and research purposes before inclusion in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Q., Yang, B., Li, X. et al. Biomarkers of cell cycle arrest, microcirculation dysfunction, and inflammation in the prediction of SA-AKI. Sci Rep 15, 8023 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92315-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92315-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Alactic base excess as an early predictor of sepsis-associated acute kidney injury: a prospective observational study

European Journal of Medical Research (2025)