Abstract

Cognitive impairment is a common health problem. However, it is often ignored in primary healthcare due to complex examination. To develop biomarkers through easily accessible blood tests, we conducted a cross-sectional analysis including 2806 healthy Chinese adults aged over 60 years old who finished the cognition assessment though Mini-Mental State Examination as well as blood routine and biochemical examination from four communities in China between July 2020 and September 2021. The blood biomarkers commonly selected by RFE and LASSO with cross-validation in the training dataset were levels of hemoglobin, high density lipoprotein, alkaline phosphatase, direct bilirubin, globulin, creatinine, magnesium, and calcium. We developed XGBoost, logistic regression and SVM models with cross-validation in the training dataset and then evaluated their performance by the receiver operating characteristic curves, F1 score and decision curve analysis in the test dataset. The accuracies of the eight biomarkers in XGBoost, logistic regression and SVM models were 0.880 (0.846–0.915), 0.851 (0.812–0.889), and 0.852 (0.814–0.890) with confirmed clinical utility to predict cognitive impairment separately. Cognitive impairment can be predicted based on blood routine and biochemical examination with good discrimination, which could be helpful in detection and intervention at primary care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cognitive impairment in older adults is a major global health concern for its huge economic and social burden1, particularly for low- and middle-income countries whose prevalence ranged from approximately 10 to 55%2,3. Subjects suffering from cognitive impairment have difficulty in the basic tasks of daily living, leading to a decrease in life quality and a remarkable increase in mortality4. Cognitive decline can also dramatically impair health in elderly individuals5. The previous studies highlighted that many disorders, like obesity, cardiovascular diseases, chronic infections, etc., had a close relationship with cognitive impairment6,7,8. However, the short duration of most primary care visits and time-consuming assessment tools intensify the challenge of motivation to assess cognition in older adults9. Moreover, some patients would try to remember answers after repeatedly finishing questionnaires, while there are no high-sensitive tools that can be repeated multiple times currently10. Furthermore, the early detection of cognitive impairment is also challenging due to the barriers associated with perceived stigma, which may compromise the physician–patient relationship10. Thus, an immediate need for identifying objective, point-of-care biomarkers from easily accessible data arises.

Blood-based biomarkers are widely accessible, minimally invasive, and less time- and cost-consuming, which is expected to play a key role in large-scale cognitive screening to accommodate the global rising incidence of cognitive impairment and to prepare the availability of therapies for cognitive impairment10. Though various proteins, including neurofilaments, Aβ, and tau, could be tested through blood samples to distinguish cognitive impairment, the methods are still complex, costly, and low sensitivity, which are not suitable in primary care11,12. Recent studies found many indicators based on blood routine and biochemical examination, which are inexpensive and accessible in primary care, including hemoglobin, platelets, the concentration of physiological ions, etc., were relevant to cognitive impairment13,14,15. Nevertheless, there remains no consensus regarding which blood markers are most suitable for the accurate assessment of cognitive impairment. On the other hand, the cognitive-related health issues that should be paid more attention still need to be explored. The blood routine and biochemical examination are sensitive to many pathological changes in the body16. The impact of cognitive impairment could also be screened out by blood indictors17, which also help to increase the concerns of cognitive-related health issues and the timing of cognitive screening in primary care. To develop an accurate, cost-effective, scalable blood biomarker-based model for cognitive decline detection in primary care, we developed a cross-sectional study among community-dwelling older adults.

Material and methods

Study design and population

This cross-sectional analysis was based on the Southwest China Natural Population Cohort Study (NPCS), an ongoing prospective population-based cohort study in community-dwelling adults18. Briefly, 24,186 participants aged 20 years or older were recruited from four communities of Sichuan Province, including 3 plain communities (< 500 m) and 1 high-altitude community (> 2000 m) between July 2020 and September 2021. In each community, temporary assessment clinics were set up in residential centers. All participants attending the study were invited to record their demographic characteristics, medical histories, and physical examination data. Among these participants, 2941 participants aged over 60 years completed the interview and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). We further excluded subjects without blood biomarker tests (n = 2), as well as those with severe physical diseases, including self-reported stroke or tumor history (n = 133). Finally, a total of 2806 community-dwelling older adults applied to blood routines and biochemical examinations were included in this analysis (Fig. 1).

Ethics declarations

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University (2,020,145) and conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was issued by all participants.

Clinical characteristics and blood biomarkers

Sociodemographic characteristics, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), education, smoking status, and alcohol drinking, were collected through the structured questionnaire conducted by trained clinicians via face-to-face interviews. We used standard Chinese cutoff points to define underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.5 ≤ BMI < 24 kg/m2), overweight (24 ≤ BMI < 28 kg/m2), and obesity (≥ 28 kg/m2)19. Level of education was measured by the highest level of education completed in China or equivalent elsewhere, which was categorized as no education, primary educational level, middle educational level, and high educational level. Smoking was defined as having at least one cigarette per day for more than 1 year. Alcohol consumption was defined as having at least one drink a week for more than half a year. Venous blood samples, routinely drawn after an overnight fast via antecubital vein puncture, were processed for blood-test indicators adhered to standard operating procedures as described in previous study18. The regular blood-test indicators included red blood cell (RBC), hemoglobin (Hb), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), platelet, white blood cell (WBC), neutrophil count (NC), monocyte (MC), lymphocyte (LC), cholesterol, low density lipoprotein (LDL), high density lipoprotein (HDL), triglyceride, fasting glucose, TyG index, total protein, globulin, albumin, albumin to globulin ratio (AGR), glutamyl transpeptidase (GT), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase (HBDH), creatine kinase (CK), total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, indirect bilirubin, bile acid, potassium, sodium, calcium, magnesium, chloride, inorganic phosphate, urea, uric acid, creatinine, and cystatin C. We also added inflammatory indicators based on the regular blood-test indicators, including NC/HDL ratio (NHR), NC/LC ratio (NLR), MC/HDL ratio (MHR), LC/HDL ratio (LHR), platelet/HDL ratio (PHR), platelet x neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (SII), monocyte x neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (SIRI), and neutrophil x platelet x monocyte-to- lymphocyte ratio (AISI).

Assessment of cognitive function

MMSE was used to assess global cognition, which had been widely used in communities due to its practicality20. The evaluation of MMSE with scores ranging from 0 to 30 encompassed five major aspects, including orientation, concentration, immediate memory, delayed recall, and language. The higher scores of MMSE indicated better cognitive function, and the cutoff of 24 points on the MMSE was used to detect cognitive impairment according to previous published findings21,22. All on-site assessments were audio-taped for purposes of quality assurance, and an experienced physician team reviewed and double-checked all data to guarantee accuracy.

Statistical analysis

Participants were categorized based on the presence or absence of cognitive impairment, and their blood test indicators were examined and compared through descriptive analysis. A four-stage strategy was employed, incorporating data preprocessing, feature selection, predictive model development, and model performance evaluation, to assess the effectiveness of blood test indicators in predicting cognitive impairment. All analyses were performed using R version 4.3.2.

Data preprocessing

In order to handle noise in the data, we applied standard deviation filtering to the numerical variables. Outliers (falling outside the 99% confidence interval) were replaced with a value that was the mean and 2.58 times standard deviation. No participants were excluded during noise filtering. We also employed the Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting (IPTW) approach to control for the potential influence of confounding factors on the model outcomes. Specifically, covariates, including gender, age, education level, BMI, smoking, and alcohol consumption, were incorporated through a weighting scheme. Then, we split the data set according to the ratio of 7:3 to construct the training set and the test set. The training set was used for feature selection and model training, and the test set was employed to test the performance of different models based on the selected indicators.

Feature selection

We employed two primary methods for feature selection using the training dataset. The first approach was the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) binomial regression, a linear regression technique with L1 regularization, which shrank coefficients to zero, thereby selecting relevant features. In the second approach, we used Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), an iterative approach that identified the optimal subset of features and systematically removed the least important ones based on their weight rankings. This process continued until the desired number of features was achieved. We employed a random forest model as the base estimator for RFE. Both of RFE and LASSO approaches were validated using tenfold cross-validation to select stable features. Finally, we selected the common indicators of two screening methods as biomarkers of cognitive impairment. Bootstrapping was also incorporated to validate the reliability of the features identified through the combined application of these two approaches.

Predictive models development

We employed three machine learning algorithms to assess the predictive capacity of blood biomarkers of cognitive impairment: a linear model (logistic regression) and two non-linear models (support vector machine, SVM; eXtreme Gradient Boosting, XGBoost). The rationale for selecting both linear and non-linear models was to capture a broad spectrum of potential relationships between the features and the outcome variable, thereby ensuring a comprehensive evaluation. XGBoost and SVM were chosen as our non-linear models since they have performed well on biomedical research and typically have fewer hyperparameters, which reduces the risk of overfitting23. Hyperparameter tuning for each model was also performed using grid search. The three models were cross-validated using tenfold cross-validation to mitigate overfitting.

Performance evaluation

The predictive performance of the selected features across the three models was evaluated in the test dataset by Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, F1 score, and decision curve analysis (DCA). The F1 score involved two metrics: Recall and Precision. Recall focused on the model’s accuracy in identifying all participants with cognitive impairment, and Precision focused on the accuracy of the model in predicting cognitive impairment among participants who were actually suffering from it. The F1 score was calculated by the formula:

Results

Characteristics of study participants

The baseline characteristics of community-dwelling older adults are shown in Table 1. The study included 2806 participants with a median age of 67.75 years (1146 men [40.84%] and 1660 women [59.16%]). Using a cut-off value of 24 (MMSE), the number of participants with cognitive impairment was 507 (18.07%). Age, gender, BMI, education, smoking, and alcohol consumption in participants with cognitive impairment were all different from those of participants without cognitive impairment. In terms of blood tests, 31 of 39 basic blood-cell and biochemical variables were associated with the risk of cognitive impairment (p < 0.10) in a univariate analysis (Table 1). It also revealed 6 of 9 markers of inflammation calculated through regular blood indicators were higher in participants with cognitive impairment.

Blood predictors selection

Considering the baseline (age, gender, BMI, education, smoking, and alcohol consumption) of participants with cognitive impairment was unbalanced with that of participants without cognitive impairment, we adjusted these covariates. The standardized mean differences (SMD) were all no more than 0.15 which were considered indicative of good balance after adjustment. (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Table 1). Then, we divided the dataset into training (n = 1964) and test (n = 842) sets to identify blood biomarkers of cognitive impairment and select a better machine learning algorithm for clinical applicability.

The features of cognitive impairment were selected by two algorithms with tenfold cross-validation. (A) The standardized mean differences of baseline characteristics before and after adjustment in the whole dataset. (B) The process of variables selected by RFE in the training dataset. When selecting 15 features, the accuracy achieved the highest point. (C) The importance score of features selected by RFE. (D) The results of ten-fold cross validation by verifying the optimal lambda in the LASSO model in the training dataset. The partial likelihood deviance (binomial deviance) curve was plotted, and dotted vertical lines were drawn based on minimum lambda and standard error criteria. (E) The importance of features selected by LASSO logistic regression. (F) Venn program of the biomarkers from two different algorithms. RFE, recursive feature elimination; LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator; Hb, hemoglobin; MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin; AGR, albumin to globulin ratio; HDL, high density lipoprotein; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; NHR, neutrophil count/high density lipoprotein ratio; NLR, neutrophil count/lymphocyte ratio.

The blood biomarker selection was performed in the training dataset. The top 15 features were chosen by RFE across a total of 48 features (Fig. 2B). The importance scores of the features selected through RFE were all more than 5 (Fig. 2C). Lasso regression was also used within the cross-validation loop to prefilter blood indicators (Fig. 2D). Thirteen potential predictors of blood indicators were chosen in the training dataset through LASSO regression (Fig. 2E). We finally remained 8 blood predictive features of cognitive impairment, which were supported by both LASSO and RFE (Fig. 2F). The 8 biomarkers of cognitive impairment were hemoglobin, HDL, direct bilirubin, ALP, globulin, creatinine, magnesium, and calcium. The bootstrapping validation showed that the biomarkers had high usage frequency, indicating a certain stability of feature selection process (Supplementary Table 2).

The development and performance of different models

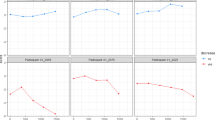

We then built three model-based algorithms, including XGBoost, SVM, and logistic models, and updated the models that they were trained on. Figure 3A show the clinical predictive accuracy of different models constructed by the biomarkers. The area under receiver operating characteristic curves (AUC) of the logistic model was 0.851 (95% CI 0.812–0.889) with 90.2% of sensitivity (95% CI 85.3–94.4%) and 95.4% of specificity (95% CI 93.1–97.1%). As for the SVM, the AUC was 0.852 (95% CI 0.814–0.890) with 90.2% of sensitivity (95% CI 84.6–95.1%) and 95.1% of specificity (95% CI 93.1–96.8%). The AUC of XGBoost was 0.880 (95% CI 0.846–0.915) with 93.0% of sensitivity (95% CI 88.1–96.5%) and 95.7% of specificity (95% CI 93.8–97.3%). The F1 scores of the biomarkers in XGBoost, SVM and logistic models were 0.93 (95%CI 0.91–0.94), 0.92 (95% CI 0.91–0.94) and 0.92 (95% CI 0.91–0.94), respectively (Fig. 3B). All of the three models were more than 0.9, and XGBoost model also performed best among the three machine algorithms.

The evaluation of the different prediction models for cognitive impairment in the test dataset. (A) ROC curves of the logistic model (red), SVM model (blue), and XGBoost (green) for cognitive impairment. The y-axis indicates the true-positive rate of the risk prediction. The x-axis indicates the false-positive rate of the risk prediction. (B) F1 scores of logistic model (red), SVM model (blue), and XGBoost (green). (C) Decision curve analysis of the risk assessment model for cognitive impairment. The y-axis measures the net benefit. The thick solid line represents the assumption that no patients have cognitive impairment. The thin solid line represents the assumption that all patients have cognitive impairment. The dotted lines (red, logistic model; blue, SVM model; green, XGBoost) represent the risk nomogram. SVM, support vector machine; XGBoost, eXtreme Gradient Boosting.

The clinical usefulness of predictive models was determined by the decision curve analysis (DCA), which could quantify the net benefits at different threshold probabilities in the test dataset (Fig. 3C). On DCA, all of the models displayed obvious clinical net benefit with a wide range of threshold probability. The threshold range of prediction probability was 0.07–0.67 in XGBoost. The logistic model and SVM model achieved 0.05–0.69 and 0.03–0.68 respectively.

Discussion

It is necessary to accommodate the implementation of public and healthcare providers focused on cognitive impairment screening and related interventions for the global rising incidence of dementia. Many indicators of easily accessible blood routine and biochemical examination have been reported to be related to cognitive impairment or provide a clue of the diseases related to cognitive impairment. Thus, we developed a predictive model based on the blood tests for cognitive impairment among older adults. We found the machine algorithm with the predictors only from blood routine and biochemical examination showed a good predictive performance of cognitive impairment. These blood biomarkers showed their strong association with cognition and the model based on them was promising for clinical transformation and practical application.

Cognition and hemoglobin

The published prospective study demonstrated a relationship between low hemoglobin level and cognitive decline in both women and men24. Nevertheless, several studies suggested there was no such significant association of hemoglobin and cognition, and the number of at-risk individuals increased considerably if higher hemoglobin cut-off points were used25. Conversely, recent studies proved that even a mild decrease in hemoglobin concentration in nonanemic participants was still deleterious26. Our result supported that the low hemoglobin level was associated with poor cognitive performance. There were some speculations of this association in some basic studies. Some researchers discovered that a chronic mild low hemoglobin level might lead to the limited oxygenation of the tissue, inducing brain hypoxia, mitochondrial dysfunction, small vessel damage, impaired permeability of the blood–brain barrier, abnormal protein aggregates, and neuronal injury27,28, which promoted neuron degeneration leading to poor cognition29. Furthermore, low hemoglobin level among older adults might be caused by protein deficiencies 30, while high protein intake was associated with a reduced risk of cognitive impairment31. Our study also found a significant joint between protein (hemoglobin, globulin, and creatinine) and cognition. We thought that the evaluation of the proper role of hemoglobin on cognitive impairment might be important in primary care.

Cognition and ionic levels

We noticed the predictive biomarkers consisted of two ionic levels, including magnesium and calcium. Recent evidence showed that dietary intake of minerals was associated with the risk of dementia32. Some researchers pointed out that the synaptic strength and plasticity depending closely on ion flux across the neuronal membrane might be one of the reasons of the link between ionic differences and cognitive impairment33.

In terms of magnesium, previous clinical studies demonstrated that there was a U-shaped association between magnesium level and cognitive impairment34. It was reported that magnesium could mediate cognitive impairment by impairing synaptic plasticity35,36. On the other hand, clinical study showed that magnesium deficiency could increase the risk of cognitive impairment in Europeans and Americans37. It has been believed that the average intake of magnesium among Chinese was higher than that of Europeans and Americans due to different dietary patterns38. Given it above, we suggested there might be a link between magnesium and cognition, and magnesium supplemental intake among Chinese older adults with cognitive impairment should be further studied.

As for calcium, it has also been suspected that both too high or too low calcium levels are deleterious in cognition. The calcium level abnormality could dysregulate calcium homeostasis, leading to amyloid accumulation and even neuron death39. Some trials reported an association between calcium supplementation and increased risk for vascular events, which was related to cognitive decline40. In contrast, lower serum calcium was considered a potentially associated factor for cognitive impairment in Asian people41. A Mendelian randomization study also showed that genetically increased calcium level was associated with the decreased risk of Alzheimer’s disease42. However, this correlation still remains unclear, and further studies are needed to identify and validate criteria for supplementation in Asian patients.

Cognition and liver function

Except for protein and iron level, liver function has also been suggested as a possible factor in the progression of cognitive impairment in previous studies. The liver might contribute to the clearance of amyloid from the brain into the peripheral circulation43. Additionally, liver function can reflect oxidative damage as well as the ability of proteins synthesis and storage, which are all risk factors for cognitive decline44. Moreover, meta-analysis demonstrated the metabolism of lipids was independently associated with cognitive impairment45. A genome-wide meta-analysis of Alzheimer’s disease also revealed the genetic involvement of the lipid system enriched in the liver, which might play an important role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease46. Our extensive liver function data from blood examination further suggested that indicators reflecting liver function, particularly ALP, direct bilirubin, globulin, and HDL, might be predictive biomarkers of cognitive impairment.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths. All biomarkers can be easily collected by blood routine and biomedical examination when patients seek primary clinical care. In addition, our predictive model was developed for a clinically relevant population, and had a good predictive ability, which would be usable and satisfactory for primary clinical use. With rapid progress made in plasma tau, Aβ, etc., our study could also provide assistance for the future study of assessing how to optimally combine plasma biomarkers in cognitive impairment at primary care. However, there are also several limitations to address. First, cross-sectional design, potential nonparticipation bias, and possible recall bias may weaken the validity of our study. Second, the major limitation is that our study had only one assessment for cognition, and care should therefore be used in interpreting these results. Thirdly, more centers and external validation data are needed to assess the biomarkers, particularly to non-Chinese populations, due to the potential influence of cultural, dietary, or environmental differences. Finally, the causality of findings needed be explored to further reveal mechanism in the future prospective study.

Conclusions

Overall, the blood-test model demonstrated good performance in predicting cognitive impairment. The biomarkers from easily accessible blood routine and biochemical examination could aid diagnosis, risk stratification, and choice of interventions for physicians in primary care. The predictive factors we extracted could also provide clues for the future study in exploring the biological progression of cognitive impairment.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Naheed, A. et al. Prevalence of dementia among older age people and variation across different sociodemographic characteristics: A cross-sectional study in Bangladesh. Lancet Reg. Health Southeast Asia 17, 100257 (2023).

Yang, L. et al. Comparison of prevalence and associated risk factors of cognitive function status among elderly between nursing homes and common communities of China: A STROBE-compliant observational study. Medicine 98, e18248 (2019).

Han, F., Luo, C., Lv, D., Tian, L. & Qu, C. Risk factors affecting cognitive impairment of the elderly aged 65 and over: A cross-sectional study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 903794 (2022).

Chen, H. J. et al. Functional-structural relationship in large-scale brain networks of patients with end stage renal disease after kidney transplantation: A longitudinal study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 41, 328 (2020).

Smith, B. M., Yao, X., Chen, K. S. & Kirby, E. D. A larger social network enhances novel object location memory and reduces Hippocampal microgliosis in aged mice. Front. Aging Neurosci. 10, 142 (2018).

Meo, S. A. et al. Effect of obesity on cognitive function among school adolescents: A cross-sectional study. Obes. Facts 12, 150 (2019).

Yaffe, K. et al. Association between hypoglycemia and dementia in a biracial cohort of older adults with diabetes mellitus. Jama Intern. Med. 173, 1300 (2013).

Cribb, D. M., Clarke, N. E., Doi, S. & Vaz, N. S. Differential impact of mass and targeted praziquantel delivery on schistosomiasis control in school-aged children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLos Neglect. Trop. D 13, e7808 (2019).

Bernstein, A. et al. Primary care provider attitudes and practices evaluating and managing patients with neurocognitive disorders. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 34, 1691 (2019).

Sabbagh, M. N. et al. Early detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in primary care. JPAD-J. Prev. Alzheim. 7, 165 (2020).

Shi, Y. et al. potential value of plasma amyloid-beta, total tau, and neurofilament light for identification of early Alzheimer’s disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 10, 3479 (2019).

Xu, H. & Xiao, S. Detection of plasma biomarker candidates for Alzheimer’s disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimer’s Dementia 14, P1173 (2018).

Wu, K. et al. Association of lower liver function with cognitive impairment in the Shenzhen ageing-related disorder cohort in China. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 1012219 (2022).

Lee, S. et al. Serum sodium in relation to various domains of cognitive function in the elderly US population. BMC Geriatr. 21, 328 (2021).

Meng, F. et al. Low hemoglobin levels at admission are independently associated with cognitive impairment after ischemic stroke: A multicenter, population-based study. Transl. Stroke Res. 11, 890 (2020).

Li, L. et al. Cardiotoxicity of intravenously administered CdSe/ZnS quantum dots in BALB/c mice. Front. Pharmacol 10, 1179 (2019).

Cedazo-Minguez, A. & Winblad, B. Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia: clinical needs, limitations and future aspects. Exp. Gerontol. 45, 5 (2010).

Fan, P. et al. The design and implementation of natural population cohort study Biobank: A multiple-center project cooperation with medical consortia in Southwest China. Front. Public Health 10, 996169 (2022).

Wang, L. et al. Body-mass index and obesity in urban and rural China: findings from consecutive nationally representative surveys during 2004–18. Lancet 398, 53 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. The relationships between plasma advanced glycation end products level and cognitive function in middle-aged and elderly Chinese subjects. Int. J. Hyg. Envir. Heal. 254, 114270 (2023).

Tombaugh, T. N. & McIntyre, N. J. The mini-mental state examination: A comprehensive review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 40, 922 (1992).

Sakurai, R. et al. MMSE cutoff discriminates hippocampal atrophy: Neural evidence for the cutoff of 24 points. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 69, 839 (2021).

Hunter, R. B. et al. Supervised machine learning applied to automate flash and prolonged capillary refill detection by pulse oximetry. Front. Physiol. 11, 564589 (2020).

Trevisan, C. et al. Low hemoglobin levels and the onset of cognitive impairment in older people: The PRO.V.A. study. Rejuv. Res. 19, 447 (2016).

Kurella, T. M. et al. Hemoglobin concentration and cognitive impairment in the renal REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study. J. Gerontol. A-Biol. 65, 1380 (2010).

Penninx, B. W. et al. Anemia and decline in physical performance among older persons. Am. J. Med. 115, 104 (2003).

He, W., Ruan, Y., Yuan, C., Luan, X. & He, J. Hemoglobin, anemia, and poststroke cognitive impairment: A cohort study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psych. 35, 564 (2020).

Oddo, M. et al. Hemoglobin concentration and cerebral metabolism in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 40, 1275 (2009).

Ferrer, I. et al. Neuronal hemoglobin is reduced in Alzheimer’s disease, argyrophilic grain disease, Parkinson’s disease, and dementia with Lewy bodies. J. Alzheimers Dis. 23, 537 (2011).

Alvarez-Nuncio, M. & Ziegler, T. R. Micronutrient status and protein-energy malnutrition in free-living older adults: A current perspective. Curr. Opin. Gastroen. 40, 99–105 (2024).

Suzuki, H. et al. Intake of seven essential amino acids improves cognitive function and psychological and social function in middle-aged and older adults: A double-blind, randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Front. Nutr. 7, 586166 (2020).

Vintimilla, R. M. et al. The link between potassium and mild cognitive impairment in Mexican-Americans. Dement Ger. Cogn. D Ex 8, 151 (2018).

Roberts, E. J. Using hippocampal slices to study how aging alters ion regulation in brain tissue. Methods 18, 150 (1999).

Chen, C. et al. Serum magnesium concentration and incident cognitive impairment: The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study. Eur. J. Nutr. 60, 1511 (2021).

Coffin, A. B., Reinhart, K. E., Owens, K. N., Raible, D. W. & Rubel, E. W. Extracellular divalent cations modulate aminoglycoside-induced hair cell death in the zebrafish lateral line. Hear. Res. 253, 42 (2009).

Isherwood, S. N., Robbins, T. W., Dalley, J. W. & Pekcec, A. Bidirectional variation in glutamate efflux in the medial prefrontal cortex induced by selective positive and negative allosteric mGluR5 modulators. J. Neurochem. 145, 111 (2018).

Kieboom, B. et al. Serum magnesium is associated with the risk of dementia. Neurology 89, 1716 (2017).

Lu, Z. et al. Relationship between whole-blood magnesium and cognitive performance among Chinese adults. Nutrients 15, 2706 (2023).

Toescu, E. C., Verkhratsky, A. & Landfield, P. W. Ca2+ regulation and gene expression in normal brain aging. Trends Neurosci. 27, 614 (2004).

Ma, L. Z. et al. Serum calcium predicts cognitive decline and clinical progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotox. Res. 39, 609 (2021).

Sato, K. et al. Lower serum calcium as a potentially associated factor for conversion of mild cognitive impairment to early Alzheimer’s disease in the Japanese Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative. J. Alzheimers Dis. 68, 777 (2019).

Jiang, Q., Hu, Y., Jin, S. & Liu, G., Genetically increased serum calcium levels reduce Alzheimer’s disease risk. (2018).

Wang, Y. R. et al. Associations between hepatic functions and plasma amyloid-beta levels-implications for the capacity of liver in peripheral amyloid-beta clearance. Mol. Neurobiol. 54, 2338 (2017).

Gao, P. Y. et al. Associations between liver function and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease pathology in non-demented adults: The CABLE study. J. Neurochem. 168, 39 (2024).

Kim, K. Y., Shin, K. Y. & Chang, K. A. Potential biomarkers for post-stroke cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 602 (2022).

Jansen, I. E. et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new loci and functional pathways influencing Alzheimer’s disease risk. Nat. Genet. 51, 404 (2019).

Funding

This research was supported by the Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province (23ZYZYTS0138).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Bosi Dong, Lei Chen; Methodology: Bosi Dong, Mengqiao He, Shuming Ji; Formal analysis and investigation: Wenjie Yang, Qiulei Hong, Mengqiao He; Writing—original draft preparation: Bosi Dong, Mengqiao He; Writing—review and editing: Bosi Dong, Anjiao Peng; Funding acquisition: Lei Chen; Resources: Lei Chen; Supervision: Yusha Tang, Anjiao Peng. Corresponding author: Correspondence to Lei Chen. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, B., He, M., Ji, S. et al. Blood predictive biomarkers for cognitive impairment among community-dwelling older adults: a cross-sectional study in China. Sci Rep 15, 7700 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92764-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92764-5