Abstract

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a leading cause of end-stage liver disease. MASLD and liver fibrosis are associated with cardiometabolic risk factors and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) while being affected by dietary/exercise patterns and social determinants of health (SDOH). However, previous studies have not assessed in conjunction exercise, diet, SDOH, and HRQOL in patients with MASLD. This was a cross-sectional study of patients with MASLD seen in hepatology clinic at University of Michigan. Participants completed validated surveys on HRQOL, diet, and physical activity, and a subset also underwent vibration controlled transient elastography (VCTE). The primary outcomes were HRQOL (measured by Short Form-8) and cirrhosis, and predictors were physical activity, dietary patterns, cardiometabolic comorbidities, and social determinants of health. The primary analysis included 304 patients, with median body mass index 32.4 kg/m2 and prevalence of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia 38%, 45%, and 42%, respectively (Table 1). The majority of the participants had a FIB-4 score of less than 1.3 and LSM of less than 8 (Table 1). HRQOL was lower with higher BMI, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and increased liver fibrosis, and higher in people with adequate fruit intake. Neighborhood-level SDOH were also associated with HRQOL. Factors associated with cirrhosis or higher liver stiffness measurement by VCTE included body mass index, diabetes, and living in an impoverished neighborhood, while increased vegetable intake and exercise were associated with lower prevalence of cirrhosis/fibrosis. In multivariable models including demographic and cardiometabolic factors, dietary patterns and SDOH were independently associated with HRQOL and cirrhosis. Cardiometabolic risk factors, physical activity, diet, and social determinants of health are associated with HRQOL and liver fibrosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is characterized by excess lipid accumulation in the liver1. MASLD affects 30% of the US adult population2 and is a leading cause of end-stage liver disease3. MASLD affects a large proportion of the population, but only a fraction of these patients develop symptomatic end-stage liver disease, with the primary risk factor for adverse outcomes being severity of underlying fibrosis4,5. However, MASLD is highly prevalent and thus is a major public health concern for millions of Americans.

In addition to its associations with cardiometabolic disorders such as obesity, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, MASLD is also associated with behavioral risk factors6: Mediterranean-style diets high in fruit, vegetables, and nuts/legumes, and low in red/processed meats and sugar-sweetened beverages, are associated with lower risk of hepatic steatosis and risk of liver-related events7, while sedentary lifestyle is associated with increased risk of liver-related mortality8. Social determinants of health also play an important role in driving disease severity9,10.

MASLD has previously been considered an asymptomatic condition until advanced liver disease develops, but more recent data suggest that is associated with decreased health related quality of life (HRQOL), especially when fibrosis and steatohepatitis are present11. While some of this effect is likely due to shared associations between MASLD and cardiometabolic disease such as obesity and diabetes, randomized studies have suggested that improvements in HRQOL occur with improvements in liver histology independently of changes in cardiometabolic profile12,13,14.

While there is existing literature regarding HRQOL in patients with MASLD, many of these studies have not considered the association of a combination of lifestyle factors such as exercise and diet, or social determinants of health, with HRQOL in patients with MASLD, or the associations of multiple lifestyle factors with fibrosis. Thus, this study aimed to consider a combination of these factors while investigating the HRQOL of patients with MASLD. Specifically, we aim to evaluate the impact of identified predictors—such as physical activity, dietary patterns, and social determinants—on HRQOL and fibrosis severity. By integrating these diverse factors, our study seeks to provide a comprehensive understanding of their collective influence.

Methods

Ethics

The study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (Ann Arbor, MI) and study procedures were conducted in concordance with good clinical practice and the Declarations of Helsinki and Istanbul. All study participants provided written informed consent.

Study population

This is a cross-sectional analysis of a prospectively enrolled cohort of patients with MASLD recruited from hepatology clinic at Michigan Medicine (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). This study included patients enrolled from March 2021 through January 2024. Inclusion criteria are objective evidence of hepatic steatosis on imaging or liver biopsy; historical evidence of steatosis is acceptable in patients with cirrhosis at time of enrollment. We also required at least one MASLD cardiometabolic criterion: (1) body mass index ≥ 25 kg/m2, (2) hemoglobin A1C ≥ 5.7% or type 2 diabetes, (3) hypertension, systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mmHg, or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 85 mmHg, (4) plasma triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL or high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ≤ 40/50 mg/dL (women/men respectively)15. Exclusion criteria include concomitant chronic liver diseases including but not limited to untreated hepatitis C infection, or active untreated chronic hepatitis B, and excess alcohol intake, which was defined as greater than 14 standard drinks per week in women and greater than 21 standard drinks per week in men. Patients with inactive HBV or treated HCV were allowed to participate. Testing for concomitant liver diseases was at the discretion of the treating hepatologist, but patients are nearly universally tested for viral hepatitis and excess alcohol intake. Patients with active treatment for malignancy were also excluded.

Participants provided blood specimens that were subsequently divided into serum, plasma, and whole blood aliquots. Participants completed standardized surveys on personal and family history of cardiometabolic disease, liver disease, and malignancy, as well as validated surveys assessing HRQOL, physical activity, diet, and alcohol intake (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; AUDIT-C) (see next section for details). Surveys were sent to patients electronically and completed remotely.

Data were also obtained from the electronic medical record, including laboratory values, medical diagnoses, and when available vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE) results. Laboratory values were collected ± 12 months from a completed survey. No specific timeframe around surveys was required for VCTE but > 70% of VCTE were within 2 years of the surveys.

Predictors

-

1.

Physical activity. Activity was measured using the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) questionnaire, which includes questions regarding amount and intensity of physical activity per week including activity at work, travel activity, recreational activity, and sedentary behavior16. Adequate exercise is defined by the Centers for Disease Control guidelines as greater than or equal to 150 min of moderate physical activity or 75 min of vigorous physical activity weekly17.

-

2.

Dietary patterns were measured using Dietary Screener Questionnaire (DSQ), which was developed by National Cancer Institute investigators and previously used in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009–201018. Weekly amounts of dietary intake for fruits, vegetables, and dairy were computed based on survey results19.

-

3.

Cardiometabolic factors were obtained from the electronic medical records. These factors include body mass index (BMI), diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and presence of cardiovascular disease defined by diagnosis codes as previously reported (Supp. Data)20.

-

4.

Social determinants of health. We evaluated three separate determinants, all at the neighborhood level measured from the National Neighborhood Data Archive22:

-

a.

Area Deprivation Index. This score includes 17 components measured at a census tract level related to education; income value and disparity, housing cost, ownership, and quality; employment and income; single parent households; and access to amenities23,24.

-

b.

Disadvantage. This score sums the percentage of households in a census tract with a single parent, receiving public assistance income, under the poverty level, or with no employed members22. It is designed as a measure of poverty.

-

c.

Affluence is the sum of percentages of people with annual income >$75,000, who completed high school, and who were employed in a managerial or professional occupation22. While also related to wealth, it more directly measures educational attainment and profession type.

-

d.

Cirrhosis. In addition to being an outcome, cirrhosis itself was evaluated as a predictor for HRQOL. Cirrhosis definition is described in the next section.

-

a.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes were HRQOL and cirrhosis, defined based on chart review of all participants. HRQOL was measured by Short Form-8 (SF8)21. For each question, raw scores were converted into scaled scores on a 0-100 scale based on the maximum and minimum possible values for each question: \(\:scaledscore=100*\frac{maxscore-score}{maxscore-minscore}\). SF8 scores were reported as overall scores and subscores to measure physical and emotional HRQOL. Criteria for cirrhosis were: (1) biopsy evidence of cirrhosis or (2) at least two of the following: (a) imaging evidence of cirrhosis including nodular liver contour or caudate lobe hypertrophy, (b) evidence of portal hypertension defined by varices seen endoscopically, otherwise-unexplained portosystemic collaterals on imaging, ascites, or hepatic encephalopathy, or (c) magnetic resonance elastography or vibration-controlled transient elastography liver stiffness measurement consistent with cirrhosis25 and the primary hepatologist was managing the patient for cirrhosis (e.g., hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance and/or screening for gastroesophageal varices). Secondary outcomes in the subset of participants with VCTE were liver stiffness measurement (LSM) as a continuous variable and as a binary variable with a threshold of LSM > 8 kPa to indicate significant liver stiffness as recommended in professional society guidelines1,26.

In all models, we reported univariable effects, and also adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity (Model 1) and Model 1 predictors plus body mass index and diabetes status (Model 2) since these factors are all known to be associated with cirrhosis risk and HRQOL6,27,28.

Statistics

Descriptive results were reported as median (interquartile range) and N (%) for continuous and discrete variables, respectively. Continuous and binary outcomes were modeled as linear or logistic regression, respectively, with 95% confidence intervals reported. A two-sided p value < 0.05 was used for statistical significance throughout. Analyses were performed in R version 4.3.2 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria) with packages tidyverse and rcompanion.

Results

Study population

At time of analysis, the study population included 304 participants who completed at least one of SF8, GPAQ, and DSQ and were included in the analysis for the cirrhosis outcome; 297 participants completed SF8, 206 DSQ, and 293 GPAQ. 220 participants also underwent VCTE and were included in a subgroup analysis (Supp. Figure 1). 22% of participants had cirrhosis (Table 1). The majority of the participants had a FIB-4 score of < 1.3 and LSM < 8 kPa. The median (interquartile range) for overall HRQOL, physical subscore for HRQOL, and emotional subscore for HRQOL were 73 (interquartile range 59–83), 72 (51–85), and 75 (63–88), respectively, out of 100 maximum points, where higher score indicates higher HRQOL (Table 1).

Among the primary analysis cohort, 164 (54%) were female and median age was 59.5 years (interquartile range 50–67 years) (Table 1). Prevalence of cardiometabolic comorbidities was high, as expected, with median BMI 32.4 kg/m2 (IQR 29.0–37.4 kg/m2); 38%, 45%, and 42% had type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, respectively (Table 1).

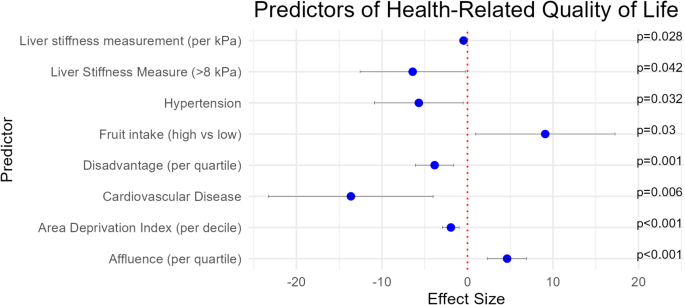

Predictors of HRQOL

First, we aimed to identify predictors of HRQOL using univariate analyses. Cardiometabolic comorbidities were associated with lower overall HRQOL scores, including higher body mass index (effect size − 0.6 per BMI point [95% confidence interval [CI] -1.0 to -0.2]); hypertension (effect size − 4.5 [95% CI -8.9 to -0.2]), diabetes (effect size − 7.3 [95% CI − 11.6 to − 2.9]), and cardiovascular disease (− 14.8 [95% CI -23.2 to -6.4]) (p < 0.05 for all) (Table 2 Unadjusted). By contrast, increased consumption of fruits/vegetables was associated with higher SF8 scores. Social determinants of health were also associated with HRQOL: each decile increase in state-level rank in Area Deprivation Index (ADI) was associated with lower HRQOL (-2.2 [95% CI -3.4 to -1.4], p < 0.001) (Table 2 Unadjusted). Similarly, higher neighborhood disadvantage score was associated with lower HRQOL (-4.4 [95% CI -6.3 to -2.5], p < 0.001) whereas higher neighborhood affluence was associated with higher HRQOL (5.2 [95% CI 3.3 to 7.0], p < 0.001) (Table 2 Unadjusted). Finally, consistent with previous studies, the presence of cirrhosis, LSM ≥ 8 kPa, or higher LSM (continuous variable) were associated with lower SF8, with effect size − 7.5 (95% CI -12.6 to -2.4) for cirrhosis, -8.0 (95% CI -13.0 to -3.0) for LSM ≥ 8 kPa, and − 0.3 (95% CI -0.6 to -0.1) per additional point of LSM) (Table 2 Unadjusted). The associations were overall similar after adjustment for age, race, and sex (Model 1) or Model 1 covariates plus BMI and diabetes (Model 2) (Fig. 1). Overall results were similar for the physical (Supp. Table 1) and emotional HRQOL (Supp. Table 2) subscores of SF8.

Effect sizes of associations between predictors and health-related quality of life. Dots represent effect size and error bars represent 95% confidence interval. Health-related quality of life was measured based on the Short Form-8 score and normalized to a 0–100 scale as detailed in Methods. Effect sizes shown are after adjustment for age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index, and diabetes, and only predictors significantly associated with health-related quality of life in these models are shown.

A multivariable model including model 2 covariates, fruit intake, affluence quartile, and LSM found that fruit intake and affluence but not LSM were significantly associated with HRQOL (Table 2 Model 2).

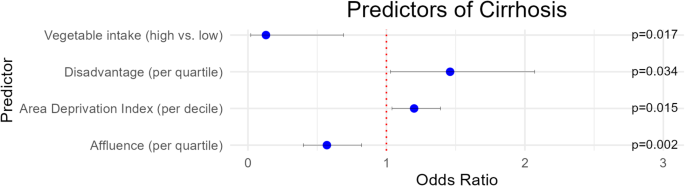

Lifestyle correlates of cirrhosis

In univariable analysis, factors associated with cirrhosis included increasing age (per-year OR 1.1 [95% CI 1.0 to 1.1], p < 0.001) and diabetes (OR 4.0 [95% CI 2.2 to 7.0], p < 0.001) (Table 3 Unadjusted). Exercise was not significantly associated with cirrhosis. Higher affluence score was associated with lower prevalence of cirrhosis (per-quartile OR 0.6 [95% CI 0.5 to 0.8], p < 0.001), and greater disadvantage (per-quartile OR 1.4 [95% CI 1.1 to 1.9], p = 0.008) and state-level rank in ADI (per decile OR 1.2 [95% CI 1.1 to 1.3], p = 0.001) were associated with greater prevalence of cirrhosis (Table 3 Unadjusted).

After adjustment for age, sex, and race (Table 3 Model 1), BMI, diabetes, higher ADI scores and greater disadvantage remained associated with higher prevalence of cirrhosis. Adequate exercise, greater intake of vegetables, and affluence also remained associated with lower prevalence of cirrhosis. After additional adjustment for BMI and diabetes (Table 3 Model 2), the associations between diet, exercise, and SDOH were largely similar (Fig. 2).

Odds ratios of associations between predictors and cirrhosis prevalence. Dots represent odds ratios and error bars represent 95% confidence interval. Odds ratios shown are after adjustment for age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index, and diabetes, and only predictors significantly associated with cirrhosis in these models are shown.

A multivariable model including model 2 covariates, vegetable intake, affluence quartile, and exercise found that vegetable intake (per cup-equivalent OR 0.1 [95% CI 0.0 to 0.7], p = 0.017) and affluence (per quartile OR 0.6 [95% CI 0.4 to 0.8], p = 0.002]) but not exercise were significantly associated with cirrhosis (Table 3 Model 2).

Subgroup analyses in patients undergoing VCTE

We conducted a sensitivity analysis where continuous LSM by VCTE was the outcome, to measure earlier stages of fibrosis than cirrhosis (Supp. Table 3). Higher BMI (per-point effect size 0.3 kPa [95% CI 0.1 to 0.5], p = 0.001) and diabetes (effect size 3.9 kPa [95% CI 1.2 to 6.6], p = 0.005) were associated with higher LSM (Supp. Table 3 Unadjusted). Adequate exercise was also associated with lower LSM (effect size − 3.5 kPa [95% CI -6.1 to -0.8], p = 0.01) (Supp. Table 3 Unadjusted).

In another sensitivity analysis, we defined significant fibrosis (defined as LSM ≥ 8 kPa) as a secondary outcome (Supp. Table 4). The results were similar to those with continuous LSM, with BMI (per-point OR 1.1 [95% CI 1.0 to 1.2], p = 0.003) and diabetes (OR 2.7 [95% CI 1.5 to 4.9], p = 0.001) associated with higher likelihood of significant fibrosis, and fruit intake (OR 0.4 [95% CI 0.1 to 1.0], p = 0.046) and adequate exercise (OR 0.4 [95% CI 0.2 to 0.7], p = 0.003) associated with lower likelihood (Supp. Table 4 Unadjusted). Higher affluence was associated with lower prevalence of significant fibrosis (per-quartile OR 0.8 [95% CI 0.6 to 1.0], p = 0.033) whereas higher ADI scores (per-decile OR 1.1 [95% CI 1.0 to 1.3], p = 0.023) were associated with higher prevalence (Supp. Table 4 Unadjusted). After adjustment for age, sex, and race (Supp. Table 4 Model 1), or Model 1 predictors plus BMI and diabetes, the overall patterns of associations were similar (Supp. Table 4 Model 2) with fruit intake and exercise though not affluence quartile retaining statistical significance.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional analysis of a prospective cohort, we characterized clinical predictors of HRQOL and lifestyle-related predictors of cirrhosis. Factors associated with lower HRQOL included living in a more impoverished neighborhood, dyslipidemia, obesity, and physical inactivity. Cirrhosis was associated with lower HRQOL, decreased physical activity, poorer diet, and neighborhood-level poverty. Poor diet and social determinants of health were independently associated with both more fibrosis and lower HRQOL in multivariable models.

Presence of MASLD has been associated with decreased HRQOL in the overall population28,29 and even compared to other etiologies of chronic liver disease, MASLD may be associated with lower HRQOL30,31. More severe histologic steatohepatitis32 and increasing hepatic fibrosis28,33 have been associated with lower HRQOL. In contrast, there has been less literature on clinical predictors of HRQOL among people with MASLD, and our finding associating SDOH, obesity, and physical inactivity to low HRQOL adds additional novelty. The association of poor diet with lower HRQOL independent of BMI and diabetes suggest that lifestyle changes in patients with MASLD may result in changes in HRQOL even if they do not result in the magnitude of weight loss typically required for improvement in liver histology34. Studies in other disease states have suggested that participating in lifestyle-based diet and exercise programs is associated with subsequent improvements in HRQOL35,36. Providers may consider touting HRQOL improvements as another benefit of lifestyle changes, even beyond reduction in severity of liver disease and cardiometabolic comorbidities. Future studies will be required to determine potential impact of selection bias, in that people uninterested in making lifestyle changes might be less likely to benefit from participating in specific programs.

Prior studies have associated physical inactivity and poor dietary patterns with risk of medical complications including liver-related complications/mortality8,37,38 and overall mortality39,40,41,42,43, but most of these studies were conducted in the general population, not necessarily those with chronic liver disease. Here, we found that poor dietary patterns and lifestyle were associated with prevalent cirrhosis in well-characterized patients with MASLD, independent of cardiometabolic comorbidities. The association between inadequate exercise or poor diet and LSM by VCTE—measuring earlier stages of fibrosis— suggest that they are relevant across the spectrum of fibrosis stage, not only in the end stages where patients may be unable to adhere to lifestyle recommendations due to medical illness. Future studies will investigate associations with incidence of cirrhosis/decompensation.

There are more limited data on associations between SDOH and advanced liver disease. We previously showed retrospectively that incidence of new cardiovascular disease and hepatic decompensation is greater in patients with MASLD living in more impoverished neighborhoods, and this association appeared to be independent of comorbidities including diabetes and obesity9. Here we report the association between SDOH and prevalence of advanced liver disease and with lower HRQOL. Mechanisms underlying these associations remain uncertain. Factors could include built environment (e.g., access to safe outdoor areas for exercise)44, food deserts/swamps45, or actual or perceived access to high-quality healthcare46,47. There is also likely to be a “duration dependence” in that persons living in disadvantaged neighborhoods for longer periods are more likely to experience health-related associations of this. It is crucial for medical providers to be aware of social factors that may limit patients’ ability to comply with treatment recommendations.

We note several limitations to this study. Due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, it is not possible to delineate direction of effect: for example, having advanced liver disease may motivate patients to change diet rather than diet causing liver disease, or it may cause poverty rather than be caused by it. Mechanisms by which SDOH influence MASLD severity and HRQOL cannot readily be determined. VCTE was not necessarily obtained concurrently with surveys though > 70% were within 2 years of one another. Dietary data included only a single FFQ, and dietary patterns may change over time, though the dietary instrument we used has been well-validated and shown to be stable in the short term18, which is adequate for a cross-sectional study; future studies in this cohort will assess changes in dietary patterns over time. Physical activity data were self reported by the participants in the study, and while the instrument we used is well-validated, it may lack the accuracy of objective measures such as accelerometers48. MASLD may be missed in non-obese populations20. Finally, our cohort had limited diversity as the majority (> 80%) of the participants identified as non-Hispanic White. Strengths include the prospective enrollment of patients in this study and careful adjudication of cirrhosis/fibrosis status.

In conclusion, we characterized the associations of diet, exercise, and SDOH with HRQOL and liver fibrosis/cirrhosis. Future studies will assess the impact of lifestyle factors on longitudinal outcomes in conjunction with blood-based biomarkers derived from the cohort.

Data availability

Individual-level data will not be made available due to privacy restrictions. Analyses may be available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author (VLC).

References

Rinella, M. E. et al. AASLD Practice Guidance on the clinical assessment and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 77(5), 1797–1835 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1097/HEP.0000000000000323

Le, M. H., Yeo, Y. H., Cheung, R., Wong, V. W. & Nguyen, M. H. Ethnic influence on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease prevalence and lack of disease awareness in the United States, 2011–2016. J. Intern. Med. Mar. 4 https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.13035 (2020).

Hirode, G., Saab, S. & Wong, R. J. Trends in the burden of chronic liver disease among hospitalized US adults. JAMA Netw. Open. 3 (4), e201997 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1997

Ng, C. H. et al. Mortality outcomes by fibrosis stage in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21 (4), 931–939e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2022.04.014 (2023).

Marengo, A., Jouness, R. I. & Bugianesi, E. Progression and natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adults. Clin. Liver Dis. 20 (2), 313–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cld.2015.10.010 (2016).

Jarvis, H. et al. Metabolic risk factors and incident advanced liver disease in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): A systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based observational studies. PLoS Med.. 17 (4), e1003100. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003100 (2020).

Chen, V. L. et al. Genetic risk accentuates dietary effects on hepatic steatosis, inflammation and fibrosis in a population-based cohort. J. Hepatol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2024.03.045

Simon, T. G. et al. Physical activity compared to adiposity and risk of liver-related mortality: Results from two prospective, nationwide cohorts. J. Hepatol. Jun. 72 (6), 1062–1069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2019.12.022 (2020).

Chen, V. L., Song, M. W., Suresh, D., Wadhwani, S. I. & Perumalswami, P. Effects of social determinants of health on mortality and incident liver-related events and cardiovascular disease in steatotic liver disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. Sep. 58 (5), 537–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.17631 (2023).

Kardashian, A., Serper, M., Terrault, N. & Nephew, L. D. Health disparities in chronic liver disease. Hepatol. 22 https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.32743 (2022).

Assimakopoulos, K., Karaivazoglou, K., Tsermpini, E. E., Diamantopoulou, G. & Triantos, C. Quality of life in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 112, 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.07.004 (2018).

Younossi, Z. M. et al. Improvements of fibrosis and disease activity are associated with improvement of Patient-Reported outcomes in patients with advanced fibrosis due to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatol. Commun. 5 (7), 1201–1211. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep4.1710 (2021).

Younossi, Z. M., Stepanova, M., Taub, R. A., Barbone, J. M. & Harrison, S. A. Hepatic fat reduction due to Resmetirom in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is associated with improvement of quality of life. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2021.07.039 (2021).

Heath, L., Aveyard, P., Tomlinson, J. W., Cobbold, J. F. & Koutoukidis, D. A. Association of changes in histologic severity of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and changes in patient-reported quality of life. Hepatol. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep4.2044 (2022).

Rinella, M. E. et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatol. 1 (6), 1966–1986. https://doi.org/10.1097/HEP.0000000000000520 (2023).

Centers for Disease Control. Physical Activity. Centers for Disease Control. Accessed May 8. (2024). https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/index.html

Healthy, P. & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Accessed Feb 6, 2023, (2030). https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health

Thompson, F. E., Midthune, D., Kahle, L. & Dodd, K. W. Development and evaluation of the National Cancer institute’s dietary screener questionnaire scoring algorithms. J. Nutr. 147 (6), 1226–1233. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.116.246058 (2017).

National Cancer Institute Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences. Data Processing & Scoring Procedures Using Current Methods (Recommended). Accessed September 5, 2024. https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/nhanes/dietscreen/scoring/current/

Wijarnpreecha, K. et al. Higher mortality among lean patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease despite fewer metabolic comorbidities. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 57 (9), 1014–1027. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.17424 (2023).

Ware, J. E., Kosinski, M., Dewey, J. E. & Gandek, B. How to score and interpret single-item health status measures: A manual for users of the SF-8 health survey. Linc. RI QualityMetric Incorporated. 15 (10), 5 (2001).

Clarke, P. & Melendez, R. Data from: National Neighborhood Data Archive (NaNDA): Neighborhood Socioeconomic and Demographic Characteristics of Census Tracts, United States, 2000–2010. (2020). https://doi.org/10.3886/E111107

Kind, A. J. et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and 30-day rehospitalization: A retrospective cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. Dec. 2 (11), 765–774. https://doi.org/10.7326/M13-2946 (2014).

Singh, G. K. Area Deprivation and widening inequalities in US Mortality, Am. J. Public Health. 93 (7), 1137–1143 (1969–1998). https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.7.1137

Hsu, C. et al. Magnetic resonance vs transient elastography analysis of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and pooled analysis of individual participants. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17 (4), 630–637e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2018.05.059 (2019).

Kanwal, F. et al. Clinical care pathway for the risk stratification and management of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 161 (5), 1657–1669. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.049 (2021).

Chen, V. L. et al. PNPLA3 genotype and diabetes identify patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease at high risk of incident cirrhosis. Gastroenterol. 7 (6), 966–977. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2023.01.040 (2023).

Papatheodoridi, M. et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A prospective Multi-center UK study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21 (12), 3107–3114e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2023.04.018 (2023).

Golabi, P. et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is associated with impairment of health related quality of life (HRQOL). Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 9, 14:18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-016-0420-z (2016).

Dan, A. A. et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 15 (6), 815–820. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03426.x (2007).

Afendy, A. et al. Predictors of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1 (5), 469–476. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04061.x (2009).

Huber, Y. et al. Health-related quality of life in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease associates with hepatic inflammation. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17 (10), 2085–2092e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2018.12.016 (2019).

Younossi, Z. et al. The burden of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: A systematic review of health-related quality of life and patient-reported outcomes. JHEP Rep. 4 (9), 100525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2022.100525 (2022).

Vilar-Gomez, E. et al. Weight loss through lifestyle modification significantly reduces features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterol. 149 (2), 367–378. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.005 (2015).

De Smedt, D. et al. The association between self-reported lifestyle changes and health-related quality of life in coronary patients: The EUROASPIRE III survey. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 21 (7), 796–805. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487312473846 (2014).

Eaglehouse, Y. L. et al. Impact of a community-based lifestyle intervention program on health-related quality of life. Qual. Life Res. 25 (8), 1903–1912. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1240-7 (2016).

Yoo, E. R. et al. Diet quality and its association with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Liver Int. 40 (4), 815–824. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.14374 (2020).

Li, W. Q. et al. Index-based dietary patterns and risk of incident hepatocellular carcinoma and mortality from chronic liver disease in a prospective study. Hepatol. 60 (2), 588–597. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27160 (2014).

Wang, Y., Nie, J., Ferrari, G., Rey-Lopez, J. P. & Rezende, L. F. M. Association of physical activity intensity with mortality: A National cohort study of 403 681 US adults. JAMA Intern. Med. Feb 1 (2), 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.6331 (2021).

Leitzmann, M. F. et al. Physical activity recommendations and decreased risk of mortality. Arch. Intern. Med. 10 (22), 2453–2460. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.22.2453 (2007).

Sotos-Prieto, M. et al. Association of changes in diet quality with total and Cause-Specific mortality. N Engl. J. Med.. 13 (2), 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1613502 (2017).

Eleftheriou, D., Benetou, V., Trichopoulou, A., La Vecchia, C. & Bamia, C. Mediterranean diet and its components in relation to all-cause mortality: Meta-analysis. Br. J. Nutr.. 120 (10), 1081–1097. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114518002593 (2018).

Reedy, J. et al. Higher diet quality is associated with decreased risk of all-cause, cardiovascular disease, and cancer mortality among older adults. J. Nutr. 144 (6), 881–889. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.113.189407 (2014).

Lovasi, G. S., Hutson, M. A., Guerra, M. & Neckerman, K. M. Built environments and obesity in disadvantaged populations. Epidemiol. Rev. 31, 7–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxp005 (2009).

Bevel, M. S. et al. Association of food deserts and food swamps with Obesity-Related Cancer mortality in the US. JAMA Oncol. 1 (7), 909–916. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2023.0634 (2023).

Berdahl, T., Biener, A., McCormick, M. C., Guevara, J. P. & Simpson, L. Mar. Annual report on children’s healthcare: Healthcare access and utilization by obesity status in the United States. Acad Pediatr. 20 (2), 175–187 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2019.11.020

Flint, S. W., Leaver, M., Griffiths, A. & Kaykanloo, M. Disparate healthcare experiences of people living with overweight or obesity in England. EClinicalMedicine. 41, 101140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101140 (2021).

Bull, F. C., Maslin, T. S. & Armstrong, T. Global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ): Nine country reliability and validity study. J. Phys. Act. Health. 6 (6), 790–804. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.6.6.790 (2009).

Funding

VLC was supported in part by NIDDK (K08 DK132312).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BCC was responsible for data collection, data analysis, and drafting of manuscript. AD was responsible for data collection, data analysis, and drafting of manuscript. JH was responsible for data collection and critical review of manuscript. IJM was responsible for data collection and critical review of manuscript. KW was responsible for a critical review of manuscript. VLC was responsible for concept development, study design, data analysis, and drafting of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

VLC received research grants from AstraZeneca, KOWA, and Ipsen, paid to University of Michigan. All other authors have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Czapla, B.C., Dalvi, A., Hu, J. et al. Physical activity, diet, and social determinants of health associate with health related quality of life and fibrosis in MASLD. Sci Rep 15, 7976 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93082-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93082-6

This article is cited by

-

Association between lifelong physical activity, physical fitness, and quality of life in older adults in Poland

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Effect of treadmill walking on cardiometabolic risk factors and liver function markers in older adults with MASLD: a randomized controlled trial

BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation (2025)

-

Exercise orchestrates systemic metabolic and neuroimmune homeostasis via the brain–muscle–liver axis to slow down aging and neurodegeneration: a narrative review

European Journal of Medical Research (2025)

-

Time trends and health inequalities of cirrhosis caused by metabolic Dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease from 1990 to 2021: A global burden of disease study

Journal of Endocrinological Investigation (2025)