Abstract

Lipoic acid (ALA), also known as 1,2-dithiolane-3-pentanoic acid, is a natural antioxidant and a critical component of mitochondrial function, where it participates in several key enzymatic processes. This organosulfur compound is derived from both plant and animal sources and was initially studied as a potential substitute for acetate. This study aims to examine the parameters related to ADME, metabolic, and structural binding analyses. Furthermore, a molecular docking analysis was performed to explore how ALA interacts with the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2. The study revealed that ALA exhibited high gastrointestinal absorption (GI absorption) and a Log Kp (skin permeation) value of -6.37 cm/s. The compound showed compliance with drug-likeness rules, including Lipinski, Ghose, Veber, Egan, and Muegge criteria, but was flagged with a Brenk alert due to the disulfide bond. It demonstrated acute oral toxicity and eye irritation/corrosion, with chemical reactivity involving epoxidation of the oxygen double bond, quinonation, and N-dealkylation processes. In contrast, there was a strong conjugation reaction with UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) and moderate reactivity with glutathione (GSH), sulfur, and adjacent carbons. Protein interactions displayed medium reactivity, while DNA reactivity was moderate. Additionally, the compound showed limited reactions in unstable oxidation processes and other pathways but exhibited affinity for various enzymes and receptors, including cyclooxygenase-2 and acetylcholinesterase. Molecular docking revealed a predominance of conventional hydrogen bonding with an affinity of -4.4 kcal/mol. These findings suggest a promising pharmacological profile, warranting further investigation into its clinical effects and applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lipoic acid (ALA), a natural antioxidant also known as 1,2-dithiolane-3-pentanoic acid, is essential in mitochondrial enzymatic activities1,2,3. This organosulfur compound, found in plants and animals, was initially considered an acetate replacement and discovered by Reed in 19514. Its first medical use was in 1959 to treat Amanita phalloides poisoning5. In the Krebs cycle, ALA acts as a cofactor in enzyme complexes, forming covalent bonds with proteins, enhancing its therapeutic potential6. Its chiral nature results in two optical isomers, R-lipoic acid and S-lipoic acid, which further expand its applications5,6.

ALA may increase cellular antioxidant potential indirectly by facilitating the absorption or synthesis of endogenous low-molecular-weight antioxidants, including ubiquinone, glutathione (GSH), and ascorbic acid. This property is further increased by reducing oxidized forms of ubiquinone, GSH, and vitamin C, as well as promoting the uptake of cysteine and cystine from the plasma, which are later converted into cysteine7,8,9,10. Apart from this, ALA can enhance intracellular levels of GSH in various cell types and tissues, while dihydrolipoic acid (DHLA) supports the conversion of cystine to cysteine, an amino acid crucial for GSH synthesis11,12,13,14.

It is believed that supplementing with antioxidants may help reduce the impacts of infections, including inflammation of the kidneys15, liver16 and heart in rats17. Since oxidative stress is recognized as an important factor in the development of various viral infections, as evidenced in previous studies]. The therapeutic importance of antioxidants against viral infections has been extensively validated through various in vitro and in vivo investigations, including their protective effect against hepatotoxicity19,20, and in rat spleen tissues21.

This acid has been investigated not only for its antioxidant properties but also for anti-inflammatory activity, which may be more relevant in the context of viral infections, including the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2. Omicron, known for its high potential for mutation and immune escape, can induce a significant increase in oxidative stress and inflammation in the body. ALA may help mitigate these effects by reducing the production of ROS, and by promoting the regeneration of endogenous antioxidants such as glutathione22,23,24,25. In addition, ALA may modulate the immune response, potentially helping to control the exacerbated inflammation associated with infection by the Omicron variant while improving cellular antioxidant status, thus offering auxiliary therapeutic support in the management of COVID-1926,27,28,29.

The use of ALA has been associated with a reduced increase in the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score and a lower 30-day all-cause mortality compared to placebo30. Despite the mortality rate being twice as high in the placebo group as in the ALA group, the statistical difference observed was marginal, likely due to the limited sample size23. Further studies with larger patient cohorts are required to confirm the potential role of ALA in the treatment of critically ill patients with COVID-191,23.

This study intends to examine the parameters related to the absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) of ALA, using ADME-based analyses, metabolic studies and structural binding analyses. In addition, a molecular docking analysis was performed to explore how ALA interacts with the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2.

Materials and methods

Absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) study

Calculation of molecular Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) parameters can be achieved using Swiss ADME software, which takes the SMILES format “C1CSS[C@@H]1CCCCC(= O)O”31,32,33,34,35. This method evaluates physicochemical properties, lipophilicity, water solubility, pharmacokinetics, and synthetic accessibility of the studied ligands36.

Computational assessment of acute toxicity using QSAR models with stoptox

To evaluate the acute toxicity of the compound, the STopTox tool was employed, utilizing Machine Learning (ML) and Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models. Predictions were performed for six toxicity endpoints: oral, dermal, inhalation, skin irritation/corrosion, ocular damage, and dermal sensitization. The model’s reliability was ensured by referencing validated experimental data35.

The chemical structure of the compound (PubChem CID: 6112) was retrieved from the PubChem database, and its SMILES notation was extracted. This SMILES code was then input into the STopTox application for computational analysis, enabling toxicity predictions based on molecular descriptors and QSAR modeling.

Prediction of toxicity of chemicals

ProTox 3.0 predicts toxicity by integrating molecular similarity, fragment-based propensities, frequently occurring features, and machine learning approaches. The platform employs CLUSTER cross-validation, which is based on fragment similarity, to enhance predictive accuracy. Built on 61 predictive models, ProTox 3.0 assesses multiple toxicity endpoints, including acute toxicity, organ toxicity, toxicological outcomes, molecular initiating events, metabolism, adverse outcome pathways (Tox21), and toxicity targets37. This comprehensive framework enables a robust evaluation of potential toxic effects based on molecular structure and known toxicological data.

Prediction of small molecule protein targets

The predictive analysis identified the most probable macromolecular targets for the bioactive compound by utilizing 2D and 3D similarity assessments. This approach leveraged a comprehensive database of 37,000 compounds, encompassing interactions with over 3,000 proteins from Homo sapiens, Mus musculus, and Rattus norvegicus38,39,40,41. The predictions were based on structural similarity, allowing for the identification of potential biological targets and interaction patterns.

Epoxidation

Epoxides are highly reactive metabolites, typically generated by cytochrome P450 through oxidation of unsaturated or multiple bonds. The specific molecular region where epoxidation occurs is referred to as the epoxidation site (SOE). A novel computational approach systematically analyzes and quantifies epoxidation reactions, achieving 94.9% accuracy in predictive modeling and 78.6% accuracy in distinguishing epoxidized from non-epoxidized compounds42. This method enhances the understanding of metabolic transformations and potential bioactivation pathways of chemical compounds.

Quinonation

Quinones, including key intermediates such as quinone imine moieties, quinone methides, and imino-methides, are highly reactive electrophilic Michael acceptors. These compounds account for over 40% of known bioactive metabolites and are primarily formed by the enzymatic action of cytochrome P450 and peroxidases. This novel predictive method is the first to comprehensively model quinone formation, capturing both single-step and multi-step processes. At the atomic level, it accurately identifies quinone formation sites with an AUC of 97.6% and predicts quinone-forming molecules with an AUC of 88.2%43. This approach enhances the understanding of quinone bioactivation and its potential toxicological implications.

Reactivity

Approximately 40% of drug candidates fail due to safety concerns arising from interactions between electrophilic drugs or their metabolites and nucleophilic biological macromolecules, such as DNA and proteins. These interactions can lead to toxicity and adverse effects, limiting the success of drug development. To address this issue, a deep convolutional neural network was developed to predict both the sites of reactivity (SOR) and the overall molecular reactivity. Cross-validation results demonstrated high predictive accuracy, with an AUC of 89.8% for SOR in DNA and 94.4% for SOR in proteins. Additionally, the model effectively distinguished reactive from non-reactive molecules, achieving AUC values of 78.7% for DNA and 79.8% for proteins44,45.

Phase 1

Phase I enzymes metabolize over 90% of FDA-approved drugs, catalyzing diverse reactions that often generate structurally unpredictable metabolites. To enhance the identification of metabolic transformations, we developed a system that labels both metabolic sites and reaction types, classifying them into five primary categories: stable oxidations, unstable oxidations, dehydrogenation, hydrolysis, and reduction. This classification enables the accurate recognition of 21 distinct Phase I reactions, covering 92.3% of the reactions recorded in our laboratory database. Using this labeling system, we trained a neural network on 20,736 human Phase I metabolic reactions, achieving a cross-validation AUC accuracy of 97.1%46. This approach improves the predictive modeling of drug metabolism and enhances the understanding of metabolic pathways.

N-dealkylation

Metabolic studies often overlook aldehyde analysis, despite their potential toxicity. While aldehydes are generally converted into carboxylic acids and alcohols through detoxification pathways, some remain highly reactive and evade metabolism, leading to adduct formation with DNA and proteins and triggering adverse effects. To address this, a predictive model was developed to identify N-dealkylation sites in metabolized substrates. The model demonstrated 97% accuracy in the first two validation cases and achieved an AUC of 94% in the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis47. This approach enhances the understanding of aldehyde reactivity and its implications in drug metabolism.

UGT conjugation

Uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs) metabolize approximately 15% of FDA-approved drugs, playing a crucial role in drug clearance and detoxification. Rapid identification of UGT metabolism sites is essential for optimizing lead compounds in drug development. The XenoSite UGT model predicts UGT-mediated metabolic sites in drug-like molecules with high accuracy. In a training dataset of 2,839 UGT substrates, the model achieved 86% accuracy in Top-1 predictions and 97% accuracy in Top-2 predictions48. This computational approach enhances drug metabolism studies by providing fast and reliable insights into UGT-mediated transformations.

ProtParam

The ProtParam tool was used to calculate various physical and chemical parameters for a given protein. The protein sequence was obtained from the PDB (PDB ID: 7TLY) in FASTA format. The computed parameters include molecular weight, theoretical pI, amino acid composition, atomic composition, extinction coefficient, estimated half-life, instability index, aliphatic index, and grand average hydropathy (GRAVY)49.

SinalP - 6.0

Signal peptides (SPs) are short amino acid sequences that regulate the secretion and translocation of proteins across cellular membranes in all living organisms. To predict SPs, we utilized the SignalP 6.0 model, a machine learning-based tool capable of detecting all five known types of SPs. This model was applied to sequence data and is designed to work effectively with metagenomic data. The tool’s ability to identify various SP types offers a comprehensive approach for analyzing protein sequences in diverse biological contexts50.

NetNGlyc − 1.0

To identify N-linked glycosylation acceptor sites in protein sequences, we used artificial neural networks trained with the surrounding sequence context. The consensus sequence Asn-Xaa-Ser/Thr (where Xaa is not Pro) was used as a basis for prediction, although not all such sequences undergo modification. In cross-validation, the model was able to identify 86% of glycosylated sequences and 61% of non-glycosylated sequences, with an overall accuracy of 76%51.

Recipient treatment

The protein target of interest, chosen based on a literature review, underwent molecular docking analysis. The target protein (PDB ID: 7TLY) and its corresponding ligand were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank, a comprehensive repository of protein 3D structures. Each entry in the PDB contains detailed information such as atomic coordinates, polymer sequences, and associated metadata. The protein inhibitors and water molecules were removed from the receptor structure using DISCOVERY STUDIO 2021 CLIENT software.

Binder treatment

For in silico analysis, ALA and Ebselen were selected for molecular docking studies. The ligand was modeled in 3D using ACD/ChemSketch software, and the 2D model was obtained from ChemSpider (CSID: 841 and CSID: 3082). The compounds were docked using a “flexible ligand with rigid protein” approach through the Autodock VINA system in the PyRx software52. After the docking process, the most stable binding conformations were evaluated with the Discovery software.

Grid and fitting calculation

The grid calculation was performed with 100 conformations using the AutoDock Vina system in the PyRx software. For the ligand-protein docking, the grid was configured with dimensions of 126 × 126 × 126 Å on the X, Y and Z axes and a spacing of 0.375 Å. The grid centre was set at coordinates 231.737, 187.05, and 260.473 Å for the 7TLY protein. The binding site was identified using ligands that had been co-crystallized with the protein in previous studies and are accessible in the Protein Data Bank. The interaction energy between these ligands and the amino acids of the 7TLY protein was computed using Discovery Studio software with RMSD < 2, which evaluates binding energy by considering components such as van der Waals interactions, electrostatic forces, and hydrogen bonds.

Results

Absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion

ALA is composed of 12 heavy atoms and has unique chemical characteristics, including the ability to accept two hydrogen bonds and donate one hydrogen bond. According to Table 1, it is possible to observe a total polar surface area (TPSA) of 87.90 Ų. This suggests that ALA has a relatively high degree of polarity, which is typically associated with good solubility in aqueous environments, enhancing its absorption in the gastrointestinal tract. ALA demonstrates a high absorption capacity of the compound.

According to the data in Table 1, ALA showed high absorption in the gastrointestinal tract, but showed low transcutaneous absorption, with a rate of -6.37 cm/s, which indicates limited dermal penetration. This low transcutaneous absorption may suggest that ALA is not effective for topical applications and may require alternative methods of administration to achieve therapeutic effects. In addition, ALA failed to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and was not identified as a P-glycoprotein (P-gp) substrate. This lack of BBB penetration further limits its potential use in central nervous system-targeted therapies. The compound also did not exhibit inhibitory activity on cytochrome P450 enzymes such as CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4. This suggests that ALA is unlikely to interfere with the metabolism of other drugs, making it a relatively safe compound for concurrent use with other treatments.

In addition, ALA met the Lipinski criteria, without violations, and showed compatibility with the parameters of Ghose, Veber, Egan, and Muegge. This indicates that ALA has favorable drug-like properties, which could facilitate its development as a potential pharmaceutical compound. The ALA bioavailability score was recorded at 0.56, which indicates a moderate potential for bioavailability, with a flag at the disulfide site in Brenk. This bioavailability score suggests that while ALA has some potential for absorption, there may be challenges related to its solubility or metabolic stability that need to be addressed for optimal therapeutic efficacy.

Prediction of toxicity parameters

The in silico toxicity prediction assays for ALA indicated a predicted LD50 of 502 mg/kg and a Predicted Toxicity Class of 4. This suggests that ALA has a moderate potential for toxicity, with a lethal dose expected at a relatively high amount compared to highly toxic substances. The analysis achieved an average similarity of 100% and a prediction accuracy of 100%. Such high prediction accuracy implies that the in silico models used are highly reliable and provide a confident estimation of the compound’s toxicity profile. However, the predictions identified activity only in nephrotoxicity (organ toxicity) with a probability of 0.55 and BBB permeability (toxicity endpoints) with a probability of 0.87 (Table 2). The higher probability associated with BBB permeability suggests that ALA may have a potential risk of central nervous system toxicity, though further studies would be needed to confirm this.

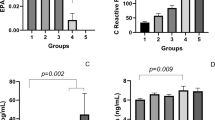

ALA demonstrated no acute inhalation toxicity, with a confidence level of 52% (Fig. 1A), and exhibited acute dermal toxicity with a confidence level of 77% (Fig. 1C). The moderate confidence in dermal toxicity indicates that ALA may cause skin irritation or other dermal effects, warranting precautions during handling. Notably, it showed acute oral toxicity with a confidence level of 80% (Fig. 1B) and eye irritation and corrosion with a confidence level of 70% (Fig. 1D). These findings highlight potential safety concerns for oral and ocular exposure, which should be considered in product development. The compound was not associated with skin sensitization, with a confidence level of 70% (Fig. 1E), and tested negative for skin irritation and corrosion, with a confidence level of 60% (Fig. 1F). This suggests that ALA may be safer in terms of skin sensitization and irritation, though some precautionary measures may still be necessary.

Small molecule metabolism

As shown in Fig. 2, ALA showed a slight reaction in the double bond of oxygen during the epoxidation process (Fig. 2A), indicating that ALA undergoes minor modifications during this process, which could influence its reactivity and metabolism in biological systems. However, there were no significant reactions in quinonation and N-dealkylation, as shown in Fig. 2B and C, respectively. This suggests that ALA is less likely to undergo these types of modifications, potentially preserving its structure and bioactivity. On the other hand, in the conjugation with UGT, there was a strong reaction with the hydroxyl group (Fig. 2D), highlighting that ALA may form conjugates that could enhance its solubility and facilitate its elimination from the body.

In interactions with GSH, ALA showed medium reactivity with sulfur and in two carbons adjacent to sulfur. This indicates that ALA may engage in detoxification processes, potentially reducing its toxicity by forming glutathione conjugates. Regarding protein, reactivity was medium with sulfur, oxygen-bound carbon, and hydroxyl groups. These interactions suggest that ALA might influence protein function, possibly by modifying key residues involved in enzymatic activity or binding. For cyanide, the reactions were few and weak, while in DNA, moderate carbon reactivity was observed (Fig. 2E). The weak reactivity with cyanide suggests that ALA is not likely to form harmful cyanide conjugates, while the moderate reactivity with DNA could indicate a potential for interaction with genetic material, requiring further investigation into its genotoxicity.

In Phase 1 reactions, ALA reacted with sulfur and with the single bond between sulfur atoms, in addition to other interactions with carbons during stable oxidation. These stable oxidation products might play a role in the metabolic activation of ALA, which could affect its pharmacological properties. However, for unstable oxidation, dehydrogenation, hydrolysis, and reductions, reactions were limited (Fig. 2F). This suggests that ALA may be relatively stable under certain metabolic conditions, which could be beneficial for its sustained activity or prolonged therapeutic effects.

Target prediction

ALA showed an affinity with targets of the Homo sapiens species, predominantly with enzymes, registering a 22% interaction rate, indicating a significant tendency to bind with these macromolecules. This strong affinity for enzymes suggests that ALA may play a role in regulating key metabolic and enzymatic pathways in human cells. Among the other classes of proteins, the compound showed a 12% affinity for family A G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), which are recognized to play vital roles in the transduction of cellular signals. This interaction with GPCRs could indicate that ALA may modulate cellular signaling pathways, potentially affecting various physiological processes. In addition, ALA showed a 10% affinity for oxidoreductases, which are enzymes involved in oxidation-reduction reactions essential for various metabolic processes. These interactions suggest that ALA could influence redox homeostasis, possibly contributing to antioxidant or pro-oxidant effects.

The in silico analysis revealed that the most likely interactions of ALA occurred with acetylcholinesterase, a hydrolase crucial in the breakdown of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, and with cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), an oxidoreductase involved in inflammation and prostaglandin production. These interactions highlight the potential of ALA in modulating neurochemical signaling and inflammatory responses, making it a promising candidate for therapeutic applications related to neurodegenerative diseases and inflammation. In addition, ALA showed a remarkable interaction with the enzyme SUMO-activating, which plays an important role in post-translational modification of proteins by regulating various cellular functions. This suggests that ALA may impact cellular regulation through modification of protein functions, further broadening its potential biological activity. However, the remaining interactions presented a significantly lower probability, suggesting a more restricted specificity of ALA in terms of its molecular targets (Fig. 3). This limited specificity may indicate that ALA is more selective in its interactions, potentially reducing the risk of off-target effects.

ALA exhibited a significant affinity with several targets in the species Mus musculus, especially the interaction with enzymes, where it registered a 26% interaction rate, indicating a strong tendency to bind with these macromolecules (Fig. 4). This further supports the idea that ALA’s primary mode of action may involve the modulation of enzymatic activity, which could influence metabolic and regulatory processes. In addition to enzymes, ALA also showed affinity with other classes of proteins, including 18% with G protein-coupled receptors of family A (GPCRs) and 14% with proteases, evidencing its versatility in interacting with different types of proteins. The broad reactivity with various protein classes points to ALA’s potential as a multitarget compound, capable of influencing diverse cellular processes. The highest probability of interaction was observed with Cyclooxygenase-2 (Oxidoreductase) and Acetylcholinesterase (Hydrolase), suggesting that these enzymes may be prime targets of ALA. This reinforces the importance of these two enzymes in ALA’s potential therapeutic effects. In contrast, interactions with other targets were detected, but with a relatively lower probability, which still underscores the potential of ALA to interact with a variety of proteins. These lower-probability interactions suggest that ALA may have additional effects that could be explored in further studies.

ALA exhibited a significant affinity with several targets in the species Rattus norvegicus, with emphasis on its interaction with enzymes, where it registered a rate of 30.2% (Fig. 5). The high affinity for enzymes in Rattus norvegicus suggests a similar mode of action in this species, further supporting the biological relevance of ALA’s interactions. In addition, the compound showed a considerable affinity with G protein-coupled receptors of family A (GPCRs), reaching 16.3%, and with voltage-gated ion channels, with 14%. These interactions point to ALA’s potential involvement in ion channel regulation and cellular signaling, which may affect various physiological processes. Although it presented a higher probability of interaction with the target Cyclooxygenase-2 (by homology) (Family A G protein-coupled receptor), interactions with other targets were observed in smaller proportions. This suggests that the primary therapeutic targets of ALA may be similar across different species, though further exploration of these interactions is necessary to fully understand its pharmacological potential.

Protein sequence analysis

The 7TLY protein (SARS-CoV-2 S B.1.1.529 Omicron variant) has a molecular weight of 178,519.52 Da and a theoretical pI of 6.68. It contains 145 negatively charged residues and 140 positively charged residues. The extinction coefficient at 280 nm is 202,695, with an absorbance of 1.135 at 0.1% (1 g/L), assuming cysteine residues form cystine, or 1.122 if reduced. The estimated half-life is 0.8 h in mammalian reticulocytes (in vitro), 10 min in yeast (in vivo), and 10 h in E. coli (in vivo). The instability index is 35.19 (stable), with an aliphatic index of 79.29 and a GRAVY of -0.215.

For chain A, the most likely signal peptide is Sec/SPI, with a probability of 0.8341, followed by Sec/SPII with a probability of 0.1651. The probabilities for other peptides (Tat/SPI, Tat/SPII, and Sec/SPIII) are extremely low, all below 0.0003 (Fig. 6A). Chain B shows similar results, with Sec/SPI as the most probable peptide (0.8342), followed by Sec/SPII (0.1649), while the probabilities for other peptides are minimal (Fig. 6B). In contrast, for chain C, the probability for Sec/SPII is considerably high at 0.9993, while the probability for Sec/SPI is very low (0.0002), and the probabilities for Tat/SPI, Tat/SPII, and Sec/SPIII are nearly zero (Fig. 6C).

In the sequence for Chain C, several N-glycosylation sites were identified. At positions 55, 57, 59, and 116, the sequences show varying potentials and jury agreement values, with a positive or negative indication for N-Glyc presence (Table 3; Fig. 7A). Similarly, Chain B reveals N-glycosylation sites, such as at positions 137, 138, 152, 158, and 210, with associated potential scores and jury agreement (Table 3; Fig. 7B). Chain C presents several positions of N-glycosylation sites, covering several positions, in which, depending on their potential, most of them presented a positive index (+) (Table 3; Fig. 7C).

Docking molecular

Ebselen (affinity − 6.369 Kcal/mol) demonstrated distinct donor and acceptor regions for hydrogen bonding (H-bonds), as illustrated in Fig. 8A. The solvent-accessible surface area was observed to range between 22.5 and 25 Ų within the ligand regions (Fig. 8B). Aromatic interactions were limited, with the only notable interaction being an edge-to-edge contact near VAL A:93 (Fig. 8C). The interpolated charge was minimal, remaining close to zero (Fig. 8D). Hydrophobicity predominantly ranged from − 1 to -3 (Fig. 8E), and the compound exhibited a neutral ionizability profile (Fig. 8F). Ebselen formed π-alkyl interactions at VAL A:93, VAL B:86, and PRO B:41, as well as conventional hydrogen bonds at GLY B:42, GLN B:43, and LYS B:40. Additionally, LYS B:40 exhibited a secondary interaction type, amide-π stacked (Fig. 8G).

ALA (affinity − 4.223 Kcal/mol) exhibited donor regions for hydrogen bonding, forming conventional hydrogen bonds at several binding sites (Fig. 9A). The solvent-accessible surface area ranged between 22.5 and 25 Ų for all protein-binding sites (Fig. 9B). Aromatic interactions were observed, notably an edge-to-edge contact near TYR A:95 (Fig. 9C). The interpolated charge showed minimal variation, remaining close to zero (Fig. 9D). Hydrophobicity predominantly ranged between − 1 and − 3 (Fig. 9E), while the ionizability profile was neutral (Fig. 9F). Molecular interactions included conventional hydrogen bonds at LYS B:40, GLY B:42, GLN B:43, and TYR A:95, π-alkyl interactions at PRO B:41, and π-sigma interactions at VAL B:86 (Fig. 9G).

Discussion

ALA contains an asymmetric carbon atom, resulting in two optical isomers: the dextrorotatory (R-ALA or + ALA) and the levorotatory (S-ALA or -ALA). The naturally occurring form of R-ALA can be found both in its free form and lysine-conjugated residues, playing an essential role as a cofactor. In contrast, synthetic ALA is a racemic mixture of the + ALA and -ALA (+/− ALA) isomers. The oxidized and reduced forms of ALA (ALA/DHLA) are potent antioxidants, neutralizing free radicals and reactive oxygen species (ROS), while also potentiating the activity of other endogenous antioxidants, such as vitamins C and E and glutathione53. In a balanced redox state, GSH is an intracellular antioxidant with the potential to neutralize free radicals through the thiol group of its cysteine54.

Lipoic acid (ALA) is safe but has limited ocular penetration due to its lipophilicity55,56. UNR844, a choline ester of ALA, enhances corneal absorption, reaching therapeutic levels in the aqueous humor. Once metabolized into dihydrolipoic acid (DHLA), it reduces disulfide bonds in lens proteins, potentially improving near vision56,57. ALA also shows good tolerability in humans and low acute toxicity in rats, with an oral LD50 exceeding 2000 mg/kg58,59,60. However, our assays showed that ALA exhibits acute oral toxicity and eye irritation and corrosion, likely due to its disulfide bonding and overall structure. This irritation may be attributed to its poor solubility, which could affect its bioavailability and interaction with ocular tissues.

ALA shows variations in its lipophilicity depending on the calculation method used. The iLOGP index indicates a lipophilicity of 1.81, while XLOGP3 has a value of 1.68. Other methods, such as WLOGP, MLOGP, and SILICOS-IT, provide values of 2.79, 1.57, and 2.34, respectively. In addition, the octanol/water partition coefficient (Log P o/w) was calculated at 2.04 (Table 2). These results suggest that ALA has activity in both aqueous and lipophilic environments61.

The inhibition of CYP450 enzymes reduces their catalytic activity, prolonging drug half-life and increasing plasma concentration. CYP2D6 metabolizes about 30% of medications, while CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 play crucial roles in drug metabolism, with CYP3A4 responsible for approximately 50%. Inhibiting these enzymes can interfere with drug metabolism, leading to toxic effects62,63,64,65. Beigi et al.66 attribute CYP2D6 inhibition to reversible competitive inhibition. However, in the conducted assays, ALA did not exhibit any inhibitory effects on CYP enzymes.

Gastrointestinal absorption of ALA appears to be influenced by several factors, including the presence of food. Research shows that the bioavailability of ALA can vary substantially with food intake. Concomitant administration of ALA with food reduces its absorption, suggesting the involvement of carrier proteins in the uptake of the compound. When ALA is ingested with food, a significant reduction in peak plasma concentrations (C max) is observed by about 30%, in addition to an approximate 20% decrease in total plasma ALA concentrations, compared to administration in the fasted state12.

ALA has a significant ability to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB), as demonstrated in previous studies67. After crossing the BBB and entering the central nervous system, ALA is rapidly internalized by cells and tissues, where it is readily converted to dihydrolipoic acid (DHLA)68.

ALA does not have toxicity alerts, but there is a Brenk alert related to the disulfide site in its chemical structure. Despite this, the compound showed no similarity to lead. The synthetic accessibility of ALA was evaluated at 2.87. In addition, ALA can chelate metals like zinc, iron, and copper while also regenerating endogenous antioxidants such as glutathione and exogenous antioxidants like vitamins C and E. These actions are achieved with minimal side effects.

Among the highlighted molecular targets, acetylcholinesterase and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) stand out due to their widespread application in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, inflammation, and pain69,70,71,72,73. Aldose reductase is crucial for addressing diabetes-related complications, while the PPAR-γ receptor plays a key role in managing type 2 diabetes and metabolic disorders74,75. Additionally, prostanoid receptors and kynurenine 3-monooxygenase have therapeutic potential for inflammation and neurodegenerative diseases76,77. Other targets, such as steroid 5-alpha-reductase, are commonly used in treating benign prostatic hyperplasia and alopecia, while thromboxane-A synthase holds significance in cardiovascular diseases78.

Furthermore, iron chelators such as heparin, deferoxamine, caffeic acid, curcumin, ALA, and phytic acid have shown potential in protecting against ferroptosis, restoring mitochondrial function, balancing iron-redox potential, and re-equilibrating Fe-RH status. This restoration of Fe-RH represents a biomarker-driven host-targeted strategy for effective clinical management and post-recovery intervention in COVID-1979.

ALA shows promise in enhancing host defenses against SARS-CoV-2 by inhibiting NF-κB signaling, reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines, and preventing oxidative depletion of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), a cofactor essential for nitric oxide (NO) synthesis. This restores NO bioavailability, improving endothelial function. Additionally, ALA scavenges reactive oxygen species (ROS), regenerates glutathione (GSH), and stimulates GSH synthesis by enhancing cysteine uptake and activating the Nrf2/ARE pathway. Nrf2 regulates genes involved in antioxidant defenses, anti-inflammatory responses, and mitochondrial protection, highlighting ALA’s potential as a therapeutic agent for managing oxidative stress and inflammation in COVID-1924,80,81. The combined use of ALA and insulin in diabetic patients may exhibit a synergistic effect against SARS-CoV-2. This suggests that ALA treatment holds significant potential in managing COVID-19 in individuals with diabetes, offering both therapeutic and supportive benefits82.

COVID-19 infection can lead to long-term effects, including redox imbalance, mitochondrial dysfunction, and chronic inflammation due to the Warburg effect. This may result in cytokine storms, chronic fatigue, or neurodegenerative diseases. Thus, patients who have a moderate to high disease condition have a reduction in GSH levels and, therefore, an increase in free radicals compared to patients with mild levels of COVID-19. Treatments like ALA and methylene blue have shown potential to enhance mitochondrial activity, counter the Warburg effect, and promote catabolism. Combining methylene blue, chlorine dioxide, and ALA could further mitigate COVID-19’s long-term impacts by stimulating catabolism83,84.

The Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 manages to evade the immunity conferred by antibodies from vaccines or previous infections due to the high number of mutations accumulated in the spike protein. To better understand this antigenic change, analyses using cryo-electron microscopy and X-ray crystal structures of the spike protein were performed, especially in the receptor-binding domain. These studies were conducted in conjunction with the monoclonal antibody S309, known for its broad neutralizing capacity against sarbecoviruses, and with the human receptor ACE285. SARS-CoV-2 enters cells by utilizing the ACE2 receptor86.

ALA is widely recognized for its potent antioxidant action, acting both endogenously and exogenously. Its active metabolite, dihydrolipoic acid, is the reduced form of ALA. This compound plays a key role in the Krebs cycle, serving as a cofactor for essential mitochondrial enzymes87. Dietary supplementation with ALA is considered safe, and its antioxidant and immunomodulatory properties have been extensively investigated88. Hydrogen bonds play a crucial role in catalysis, especially in asymmetric catalysis, as discussed by89. Organic chemists have identified that small molecules containing hydrogen bond donors, such as the functional groups OH, NH, and SH, are effective in catalyzing various reactions that involve the formation of bonds between heteroatoms and carbons, including CC and C bonds90.

Signal peptides (SPs) are short N-terminal amino acid sequences that direct proteins to the secretory pathway (Sec) in eukaryotes and facilitate translocation across the plasma membrane (internal) in prokaryotes50. Since comprehensive experimental identification of SPs is impractical, computational prediction of SPs is of significant importance in cellular biology research91. The signal peptidase complex (SPC) cleaves SPs from their non-functional precursor forms and also aids in the maturation of many viral proteins, including the precursor proteins of most flaviviruses (e.g., Zika, Dengue, and Hepatitis C viruses), HIV, and SARS-CoV92,93,94,95,96. The highest values were observed in the C-terminal region of the protein, where the probability for Sec/SPII is significantly high at 0.9993, while the probability for Sec/SPI is very low (0.0002). Additionally, the probabilities for Tat/SPI, Tat/SPII, and Sec/SPIII are nearly zero.

Ebselen is a well-known covalent inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 3Clpro, however, the inhibitory activity of myricetin has been reported to surpass that of Ebselen, a positive control inhibitor. Ebselen exhibits inhibitory effects at a concentration of 10 µM97,98. In comparison, the Ginkgo biloba extract (GBE50) demonstrated a more potent anti-SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro effect, with an IC50 value of 17.19 µg/mL after 63 min of pre-incubation. Notably, 18 components in GBE50 were capable of covalently modifying SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro. Among these, 11 ingredients were identified as strong to moderate inhibitors in anti-SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro assays99,100,101,102.

The biological effects of Ebselen are related to its antioxidant potential and the interaction with cysteine residues in proteins through selenyl-sulfide. As a result, ebselen binds to viral proteins and makes it difficult for the virus to replicate. Among the studies with inflammation, addressing inflammation in the lungs, Ebselen being transported by blood plasma, interacts with cysteine in the serum albumin protein, concentrating in the pulmonary system and presenting an anti-inflammatory action103,104,105,106.

Ebselen formed molecular interactions with VAL A:93, VAL B:86, PRO B:41, GLY B:42, GLN B:43, and LYS B:40. Similarly, α-lipoic acid demonstrated activity at the binding sites LYS B:40, GLY B:42, GLN B:43, TYR A:95, PRO B:41, and VAL B:86. These results reveal overlapping interaction sites between Ebselen and α-lipoic acid (VAL B:86, PRO B:41, GLY B:42, GLN B:43, and LYS B:40), suggesting the potential for comparable biological effects. However, further in vitro assays are necessary to elucidate and confirm the specific activities of α-lipoic acid within these contexts.

None of the binding sites observed for ALA and ebselen involved N-glycosylation, a common post-translational modification characterized by the covalent addition of oligosaccharides to asparagine residues in polypeptide chains. N-glycosylation can be summarized in three stages: first, the formation of the lipid-linked oligosaccharide donor (LLO); second, the cotranslational transfer of the glycan to the nascent polypeptide chain, in the Asn-X-Ser/Thr pattern (where X represents any amino acid except Pro); and finally, the processing of the oligosaccharide chain Glc₃Man₉GlcNAc₂ in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi107,108,109,110.

Conclusion

The results suggest that ALA exhibits a favorable pharmacokinetic profile, characterized by effective gastrointestinal absorption, though with limited skin penetration and blood-brain barrier permeability. Its compliance with Lipinski’s rule of five and absence of cytochrome P450 inhibition underscore its therapeutic potential. However, the findings also note warnings from Brenk and the compound’s limited similarity to established safe compounds. Molecular docking studies demonstrate ALA’s selective interaction with various functional groups and biological targets, providing strong evidence for its antioxidant and enzyme-modulating properties. Future research should focus on exploring ALA’s clinical applications, particularly in its antioxidant effects and enzyme modulation.

In silico molecular docking analysis with the target protein, crystal structure of the SARS-CoV-2 S synthase B.1.1.529 Omicron variant (7TLY) and the Ebselen ligand, including analysis of hydrogen bonds (H-Bonds) (A), solvent-accessible surface area (SAS) (B), aromatics (C), interpolated charges (D), hydrophobicity (E), ionizability (F), and 2D binding analysis with the target protein (G).

In silico molecular docking analysis with the target protein, crystal structure of the SARS-CoV-2 S synthase B.1.1.529 Omicron variant (7TLY) and the lipoic acid ligand, including analysis of hydrogen bonds (H-Bonds) (A), solvent-accessible surface area (SAS) (B), aromatics (C), interpolated charges (D), hydrophobicity (E), ionizability (F), and 2D binding analysis with the target protein (G).

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper.

Abbreviations

- ALA:

-

Lipoic acid

- GSH:

-

Glutathione

- UGT:

-

UDP-glucuronosyltransferase

- DHLA:

-

Dihydrolipoic acid

- ROS:

-

Reactive Oxygen Species

- ADME:

-

Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion

- SMILES:

-

Simplified molecular-input line-entry system

- SOE:

-

Epoxidation site

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- SOR:

-

Sites of reactivity

- UGTs:

-

Uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferases

- PDB:

-

Protein Data Bank

- TPSA:

-

Total polar surface area

- BBB:

-

Blood-brain barrier

- P-gp:

-

P-glycoprotein

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- COX-2:

-

Cyclooxygenase-2

- GPCRs:

-

G protein-coupled receptors of family A

- ML:

-

Machine Learning

- QSAR:

-

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- ROC:

-

Receiver Operating Characteristic

- DHLA:

-

dihydrolipoic acid

- SPs:

-

Signal peptides

- SPC:

-

signal peptidase complex

References

Tripathi, A. K. et al. Insights moleculares e terapêuticos do ácido alfa-lipóico Como uma molécula potencial Para prevenção de Doenças. Revista Brasileira De Farmacognosia. 33 (2), 272–287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43450-023-00370-1 (2023).

Kang, L. et al. Structure–activity relationship investigation of coumarin–chalcone hybrids with diverse side-chains as acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors. Mol. Diversity. 22 (4), 893–906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11030-018-9839-y (2018).

Wang, K. et al. Inhibition of inflammation by Berberine: molecular mechanism and network Pharmacology analysis. Phytomedicine 128, 155258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2023.155258 (2024).

Reed, L. J., Debusk, B. G., Gunsalus, I. C. & Hornberger CSJr. Crystalline alpha-lipoic acid; a catalytic agent associated with pyruvate dehydrogenase. Sci. (New York. N.Y.), 114 (2952), 93–94. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.114.2952.93 (1951).

Bock, E. & Schneeweiss, J. Ein beitrag Zur therapie der neuropathia diabetica. Munchner Med. Wochenschrift. 43, 1911–1912 (1959).

Brookes, M. H., Golding, B. T., Howes, D. A. & Hudson, A. T. Proof that the absolute configuration of natural α-lipoic acid is R by the synthesis of its enantiomer [(S)-(–)-α-lipoic acid] from (S)-malic acid. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 19, 1051–1053 (1983).

Pisoschi, A. M. et al. Mitigação do estresse oxidativo Por antioxidantes — uma Visão geral sobre Sua Química e influências no Estado de Saúde. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 209, 112891 (2021).

Li, R., Luo, P., Guo, Y., He, Y. & Wang, C. Clinical features, treatment, and prognosis of SGLT2 inhibitors induced acute pancreatitis. Exp. Opin. Drug Saf. 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/14740338.2024.2396387 (2024).

Lu, Q. et al. Nitrogen-containing flavonoid and their analogs with diverse B-ring in acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase Inhibition. Drug Dev. Res. 81 (8), 1037–1047. https://doi.org/10.1002/ddr.21726 (2020).

Li, X. et al. The association of post–embryo transfer SARS-CoV-2 infection with early pregnancy outcomes in in vitro fertilization: a prospective cohort study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 230 (4), 436e1. 436.e12 (2024).

Suh, J. H., Wang, H., Liu, R. M., Liu, J. & Hagen, T. M. (R)-alpha-lipoic acid reverses the age-related loss in GSH redox status in post-mitotic tissues: evidence for increased cysteine requirement for GSH synthesis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 423 (1), 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2003.12.020 (2004).

Theodosis-Nobelos, P., Papagiouvannis, G., Tziona, P. & Rekka, E. A. Lipoic acid. Kinetics and pluripotent biological properties and derivatives. Mol. Biol. Rep. 48 (9), 6539–6550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-021-06643-z (2021).

Yin, M. et al. sc2GWAS: a comprehensive platform linking single cell and GWAS traits of human. Nucleic Acids Res. gkae1008. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae1008 (2024).

Ji, D. et al. Role of TRPM2 in brain tumours and potential as a drug target. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 43 (4), 759–770. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41401-021-00679-4 (2022).

Karağaç, M. S. et al. Esculetin improves inflammation of the kidney via gene expression against doxorubicin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats: in vivo and in Silico studies. Food Bioscience. 62, 105159 (2024).

Kizir, D. et al. The protective effects of Esculetin against Doxorubicin-Induced hepatotoxicity in rats: insights into the modulation of caspase, FOXOs, and heat shock protein pathways. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 38 (10), e23861 (2024).

Öztürk, N. et al. Exploring Esculetin’s protective role: countering Doxorubicin-Induced oxidative stress in rat heart. Laboratuvar Hayvanları Bilimi Ve Uygulamaları Dergisi. 4 (1), 44–52 (2024).

Beck, M. A., Handy, J. & Levander, O. A. The role of oxidative stress in viral infections. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 917 (1), 906–912. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05456.x (2000).

Özturk, N., Ceylan, H. & Demir, Y. The hepatoprotective potential of Tannic acid against doxorubicin-induced hepatotoxicity: insights into its antioxidative, anti‐inflammatory, and antiapoptotic mechanisms. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 38 (8), e23798 (2024).

Köroğlu, Z. et al. Protective effects of Esculetin against doxorubicin-induced toxicity correlated with oxidative stress in rat liver: in vivo and in Silico studies. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 38 (4), e23702 (2024).

Kizir, D., Karaman, M., Demir, Y. & Ceylan, H. Effect of Tannic acid on doxorubicin-induced cellular stress: expression levels of heat shock genes in rat spleen. Biotechnol. Appl. Chem. 71 (6), 1339–1345. https://doi.org/10.1002/bab.2633 (2024).

Hu, S. et al. Races of small molecule clinical trials for the treatment of COVID-19: an up-to-date comprehensive review. Drug Dev. Res. 83 (1), 16–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/ddr.21895 (2022).

Cheng, Y. et al. The investigation of Nfκb inhibitors to block cell proliferation in OSCC cells lines. Curr. Med. Chem. https://doi.org/10.2174/0109298673309489240816063313 (2024).

Feng, H. et al. Orexin neurons to sublaterodorsal tegmental nucleus pathway prevents sleep onset REM sleep-Like behavior by relieving the REM sleep pressure. Research 7, 0355. https://doi.org/10.34133/research.0355 (2024).

Gao, Y. et al. Dual signal light detection of beta-lactoglobulin based on a porous silicon Bragg mirror. Biosens. Bioelectron. 204, 114035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2022.114035 (2022).

Smith, A. R. & Hagen, T. M. Alpha-lipoic acid as a pleiotropic compound with potential therapeutic use in diabetes and other chronic diseases. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 15 (1), 45 (2023).

Gao, Y. et al. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors derived from β-elemene scaffold. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 38 (1), 2195991. https://doi.org/10.1080/14756366.2023.2195991 (2023).

Zhang, Q. et al. Multi targeted therapy for Alzheimer’s disease by Guanidinium-Modified Calixarene and cyclodextrin Co-Assembly loaded with insulin. ACS Nano. 18 (48), 33032–33041. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.4c05693 (2024).

Zhong, M. et al. Active-Controlled study to evaluate the clinical efficacy and safety of α-Lipoic acid for critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Front. Med. 8, 566609. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.566609 (2022).

Nguyen, M., Aulick, S. & Kennedy, C. Effectiveness of vitamin D and Alpha-Lipoic acid in COVID-19 infection: A literature review. Cureus 16 (4), e59153. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.59153 (2024).

Daina, A., Michielin, O. & Zoete, V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 7, 42717. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42717 (2017).

Türkeş, C., Demir, Y. & Beydemir, Ş. In vitro inhibitory activity and molecular Docking study of selected natural phenolic compounds as AR and SDH inhibitors. ChemistrySelect 7 (48), e202204050 (2022).

Buza, A. et al. Novel benzenesulfonamides containing a dual Triazole moiety with selective carbonic anhydrase Inhibition and anticancer activity. RSC Med. Chem. (2024).

Güleç, Ö. et al. Novel spiroindoline derivatives targeting aldose reductase against diabetic complications: bioactivity, cytotoxicity, and molecular modeling studies. Bioorg. Chem. 145, 107221 (2024a).

Güleç, Ö. et al. Bioactivity, cytotoxicity, and molecular modeling studies of novel sulfonamides as dual inhibitors of carbonic anhydrases and acetylcholinesterase. J. Mol. Liq. 410, 125558 (2024b).

Türkeş, C. et al. N-substituted phthalazine sulfonamide derivatives as non‐classical aldose reductase inhibitors. J. Mol. Recognit. 35 (12), e2991 (2022).

Ali, J., Camilleri, P., Brown, M. B., Hutt, A. J. & Kirton, S. B. In Silico prediction of aqueous solubility using simple QSPR models: the importance of phenol and phenol-like moieties. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 52 (11), 2950–2957. https://doi.org/10.1021/ci300447c (2012).

Borba, J. V. B. et al. STopTox: an in Silico alternative to animal testing for acute systemic and topical toxicity. Environ. Health Perspect. 130 (2), 27012. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP9341 (2022).

Buza, A. et al. Discovery of novel benzenesulfonamides incorporating 1,2,3-triazole scaffold as carbonic anhydrase I, II, IX, and XII inhibitors. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 239, 124232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.124232 (2023).

Banerjee, P., Eckert, A. O., Schrey, A. K. & Preissner, R. ProTox-II: a webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res. 46 (W1), W257–W263. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky318 (2018).

Banerjee, P., Kemmler, E., Dunkel, M., Preissner, R. & ProTox 3.0: a webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res. 52(W1), W513–W520. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae303 (2024).

Hughes, T. B., Miller, G. P. & Swamidass, S. J. Modeling epoxidation of Drug-like molecules with a deep machine learning network. ACS Cent. Sci. 1 (4), 168–180. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscentsci.5b00131 (2015a).

Hughes, T. B. & Swamidass, S. J. Deep learning to predict the formation of Quinone species in drug metabolism. Chem. Res. Toxicol. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00385 (2017).

Hughes, T. B., Miller, G. P. & Swamidass, S. J. Site of reactivity models predict molecular reactivity of diverse chemicals with glutathione. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 28 (4), 797–809. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrestox.5b00017 (2015b).

Hughes, T. B., Dang, N. L., Miller, G. P. & Swamidass, S. J. Modeling reactivity to biological macromolecules with a deep multitask network. ACS Cent. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscentsci.6b00162 (2016).

Dang, N. L., Matlock, M. K., Hughes, T. B. & Swamidass, S. J. The metabolic Rainbow: deep learning phase I metabolism in five colors. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 60 (3), 1146–1164. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00836 (2020).

Dang, N. L., Hughes, T. B., Miller, G. P. & Swamidass, S. J. Computationally assessing the bioactivation of drugs by N-Dealkylation. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 31 (2), 68–80. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrestox.7b00191 (2018).

Dang, N. L., Hughes, T. B., Krishnamurthy, V. & Swamidass, S. J. A simple model predicts UGT-Mediated metabolism. Bioinformatics https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btw350 (2016).

Walker, J. M. (ed). The proteomics protocols handbook. Humana press. (2005). https://doi.org/10.1385/1592598900

Teufel, F. et al. SignalP 6.0 predicts all five types of signal peptides using protein Language models. Nat. Biotechnol. 40 (7), 1023–1025. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-021-01156-3 (2022).

Gupta, R. & Brunak, S. Prediction of glycosylation across the human proteome and the correlation to protein function. Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing. Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing, 310–322. (2002).

Trott, O. & Olson, A. J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of Docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31 (2), 455–461. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.21334 (2010).

Kagan, V. E. et al. Dihydrolipoic acid—a universal antioxidant both in the membrane and in the aqueous phase: reduction of Peroxyl, ascorbyl and chromanoxyl radicals. Biochem. Pharmacol. 44 (8), 1637–1649. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-2952(92)90482-X (1992).

Checconi, P. et al. Role of Glutathionylation in Infection and Inflammation. Nutrients, 11(8), (2019). (1952). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081952

Cagini, C. et al. Study of alpha-lipoic acid penetration in the human aqueous after topical administration. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 38 (6), 572–576. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9071.2010.02319.x (2010).

Korenfeld, M. S. et al. Topical lipoic acid choline ester eye drop for improvement of near visual acuity in subjects with presbyopia: a safety and preliminary efficacy trial. Eye (London England). 35 (12), 3292–3301. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-020-01391-z (2021).

Garner, W. H. & Garner, M. H. Protein disulfide levels and Lens elasticity modulation: applications for presbyopia. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 57 (6), 2851–2863. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.15-18413 (2016).

Cremer, D. R., Rabeler, R., Roberts, A. & Lynch, B. Long-term safety of alpha-lipoic acid (ALA) consumption: A 2-year study. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacology: RTP. 46 (3), 193–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2006.06.003 (2006a).

Cremer, D. R., Rabeler, R., Roberts, A. & Lynch, B. Safety evaluation of alpha-lipoic acid (ALA). Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacology: RTP. 46 (1), 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2006.06.004 (2006b).

Li, G. et al. α-Lipoic acid prolongs survival and attenuates acute kidney injury in a rat model of sepsis. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 41 (7), 459–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1681.12244 (2014).

Packer, L., Witt, E. H. & Tritschler, H. J. Alpha-lipoic acid as a biological antioxidant. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 19 (2), 227–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/0891-5849(95)00017-R (1995).

Orr, S. T. et al. Mechanism-based inactivation (MBI) of cytochrome P450 enzymes: structure-activity relationships and discovery strategies to mitigate drug-drug interaction risks. J. Med. Chem. 55 (11), 4896–4933. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm300065h (2012).

Deodhar, M. et al. Mechanisms of CYP450 Inhibition: Understanding Drug-Drug interactions due to Mechanism-Based Inhibition in clinical practice. Pharmaceutics 12 (9), 846. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12090846 (2020).

Zhao, M. et al. Cytochrome P450 enzymes and drug metabolism in humans. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (23), 12808. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222312808 (2021).

Tan, B. H., Ahemad, N., Pan, Y. & Ong, C. E. Mechanism-based inactivation of cytochromes P450: implications in drug interactions and pharmacotherapy. Xenobiotica; Fate Foreign Compd. Biol. Syst. 54 (9), 575–598. https://doi.org/10.1080/00498254.2024.2395557 (2024).

Beigi, T. et al. Protective role of ellagic acid and taurine against Fluoxetine induced hepatotoxic effects on biochemical and oxidative stress parameters, histopathological changes, and gene expressions of IL-1β, NF-κB, and TNF-α in male Wistar rats. Life Sci. 304, 120679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2022.120679 (2022).

Biewenga, G. P., Haenen, G. R. & Bast, A. The Pharmacology of the antioxidant lipoic acid. Gen. Pharmacology: Vascular Syst. 29 (3), 315–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-3623(96)00474-0 (1997).

Lu, X. et al. Development of L-carnosine functionalized iron oxide nanoparticles loaded with dexamethasone for simultaneous therapeutic potential of blood brain barrier crossing and ischemic stroke treatment. Drug Deliv. 28 (1), 380–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/10717544.2021.1883158 (2021).

Walczak-Nowicka, Ł. J. & Herbet, M. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases and the role of acetylcholinesterase in their pathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (17), 9290. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22179290 (2021).

Javed, M. A. et al. Diclofenac derivatives as concomitant inhibitors of cholinesterase, monoamine oxidase, cyclooxygenase-2 and 5-lipoxygenase for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: synthesis, pharmacology, toxicity and Docking studies. RSC Adv. 12 (35), 22503–22517. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2ra04183a (2022).

Moussa, N. & Dayoub, N. Exploring the role of COX-2 in Alzheimer’s disease: potential therapeutic implications of COX-2 inhibitors. Saudi Pharm. Journal: SPJ : Official Publication Saudi Pharm. Soc. 31 (9), 101729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2023.101729 (2023).

Artasensi, A., Pedretti, A., Vistoli, G. & Fumagalli, L. Type 2 diabetes mellitus: A review of Multi-Target drugs. Molecules (Basel Switzerland). 25 (8), 1987. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25081987 (2020).

Kumar, M., Choudhary, S., Singh, P. K. & Silakari, O. Addressing selectivity issues of aldose reductase 2 inhibitors for the management of diabetic complications. Future Med. Chem. 12 (14), 1327–1358 (2020).

Rauf, A. et al. Neuroinflammatory markers: key indicators in the pathology of neurodegenerative diseases. Molecules (Basel Switzerland). 27 (10), 3194. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27103194 (2022).

Lohitaksha, K. et al. Eicosanoid signaling in neuroinflammation associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 976, 176694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2024.176694 (2024).

Chislett, B. et al. 5-alpha reductase inhibitors use in prostatic disease and beyond. Translational Androl. Urol. 12 (3), 487–496. https://doi.org/10.21037/tau-22-690 (2023).

Mesitskaya, D. F. et al. A new target for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Agents Med. Chem. 16 (2), 81–87. https://doi.org/10.2174/1871525716666180724115132 (2018).

Naidu, S. A. G., Clemens, R. A. & Naidu, A. S. SARS-CoV-2 infection dysregulates host Iron (Fe)-Redox homeostasis (Fe-R-H): role of Fe-Redox regulators, ferroptosis inhibitors, anticoagulants, and Iron-Chelators in COVID-19 control. J. Diet. Supplements. 20 (2), 312–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/19390211.2022.2075072 (2023).

Petri, S., Körner, S. & Kiaei, M. Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway: key mediator in oxidative stress and potential therapeutic target in ALS. Neurol. Res. Int. 2012, 878030. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/878030 (2012).

Rochette, L. & Ghibu, S. Mechanics insights of Alpha-Lipoic acid against cardiovascular diseases during COVID-19 infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (15), 7979. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22157979 (2021).

Jalilpiran, Y. et al. The effect of Alpha-lipoic acid supplementation on endothelial function: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytother. Res. 35 (5), 2386–2395. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.6959 (2021).

Iciek, M., Bilska-Wilkosz, A., Kozdrowicki, M. & Górny, M. Reactive sulfur compounds in the fight against COVID-19. Antioxid. (Basel Switzerland). 11 (6), 1053. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11061053 (2022).

Cure, E. & Cumhur Cure, M. Alpha-lipoic acid May protect patients with diabetes against COVID-19 infection. Med. Hypotheses. 143, 110185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2020.110185 (2020).

Polonikov, A. Endogenous deficiency of glutathione as the most likely cause of serious manifestations and death in COVID-19 patients. ACS Infect. Dis. 6 (7), 1558–1562. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00288 (2020).

Schwartz, L. et al. Toxicity of the Spike protein of COVID-19 is a redox shift phenomenon: A novel therapeutic approach. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 206, 106–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2023.05.034 (2023).

McCallum, M. et al. Structural basis of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron immune evasion and receptor engagement. Sci. (New York N Y). 375 (6583), 864–868. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn8652 (2022).

Lopez-Leon, S. et al. More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-95565-8 (2021).

Ikematsu, H., Nakamura, K., Harashima, S., Fujii, K. & Fukutomi, N. Safety assessment of coenzyme Q10 (Kaneka Q10) in healthy subjects: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacology: RTP. 44 (3), 212–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2005.12.002 (2006).

Yao, J. K. & Keshavan, M. S. Antioxidants, redox signaling, and pathophysiology in schizophrenia: an integrative view. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 15 (7), 2011–2035. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2010.3603 (2011).

Vafaee, F., Derakhshani, M., Ghasemzadeh Rahbardar, M. & Hosseinzadeh, H. Alpha-lipoic acid, as an effective agent against toxic elements: a review. Naunyn. Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol., 1–28. (2024).

Nielsen, H., Tsirigos, K. D., Brunak, S. & von Heijne, G. A brief history of protein sorting prediction. Protein. J. 38 (3), 200–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10930-019-09838-3 (2019).

Estoppey, D. et al. The natural product Cavinafungin selectively interferes with Zika and dengue virus replication by Inhibition of the host signal peptidase. Cell. Rep. 19 (3), 451–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.071 (2017).

Oostra, M. et al. Localization and membrane topology of coronavirus nonstructural protein 4: involvement of the early secretory pathway in replication. J. Virol. 81 (22), 12323–12336. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01506-07 (2007).

Snapp, E. L. et al. Structure and topology around the cleavage site regulate post-translational cleavage of the HIV-1 gp160 signal peptide. eLife 6, e26067. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.26067 (2017).

Suzuki, R. et al. Signal peptidase complex subunit 1 participates in the assembly of hepatitis C virus through an interaction with E2 and NS2. PLoS Pathog. 9 (8), e1003589. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003589 (2013).

Zhang, R. et al. A CRISPR screen defines a signal peptide processing pathway required by flaviviruses. Nature 535 (7610), 164–168. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature18625 (2016).

Barletta, M. A. et al. Coenzyme Q10 + alpha lipoic acid for chronic COVID syndrome. Clin. Experimental Med. 23 (3), 667–678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10238-022-00871-8 (2023).

Xiong, Y. et al. Flavonoids in Ampelopsis grossedentata as covalent inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro: Inhibition potentials, covalent binding sites and inhibitory mechanisms. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 187, 976–987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.07.167 (2021).

Yan, Y. M. et al. Discovery of anti-SARS-CoV-2 agents from 38 Chinese patent drugs toward respiratory diseases via Docking screening. Med. Plant. Biology. 2 (1). https://doi.org/10.48130/MPB-2023-0009 (2023).

Chen, S., Yang, Z., Sun, W., Tian, K., Sun, P.,… Wu, J. (2024). TMV-CP based rational design and discovery of α-Amide phosphate derivatives as anti plant viral agents. Bioorganic Chemistry, 147,107415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioorg.2024.107415.

Cao, D., Zhou, X., Guo, Q., Xiang, M., Bao, M., He, B.,… Mao, X. (2024). Unveiling the role of histone deacetylases in neurological diseases: focus on epilepsy. Biomarker Research, 12(1), 142. 10.1186/s40364-024-00687-6.

Liu, H., Tang, Y., Zhou, Q., Zhang, J., Li, X., Gu, H.,… Li, Y. (2024). The Interrelation of Blood Urea Nitrogen-to-Albumin Ratio with Three-Month Clinical Outcomes in Acute Ischemic Stroke Cases: A Secondary Analytical Exploration Derived from a Prospective Cohort Study. International Journal of General Medicine, 17, 5333–5347. 10.2147/IJGM.S483505.

Qi, Y., Si, Y., Du, S., Liang, J., Wang, K.,… Zheng, J. (2019). Recent advances in the chemical synthesis and semi-synthesis of poly-ubiquitin-based proteins and probes.Science China Chemistry, 62(3), 299–312. 10.1007/s11426-018-9401-8.

Qi, Y., Zheng, J. & Liu, L. Mirror-image protein and peptide drug discovery through mirror-image phage display. Chem 10 (8), 2390–2407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chempr.2024.06.004 (2024).

Zhang, Y. N. et al. Discovery and characterization of the covalent SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro inhibitors from Ginkgo biloba extract via integrating chemoproteomic and biochemical approaches. Phytomedicine: Int. J. Phytotherapy Phytopharmacology. 114, 154796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2023.154796 (2023).

Wagner, G., Schuch, G., Akerboom, T. P. & Sies, H. Transport of Ebselen in plasma and its transfer to binding sites in the hepatocyte. Biochem. Pharmacol. 48 (6), 1137–1144. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-2952(94)90150-3 (1994).

Jin, Z. et al. Structure of Mpro from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature 582 (7811), 289–293. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y (2020).

Martini, F. et al. A multifunctional compound Ebselen reverses memory impairment, apoptosis and oxidative stress in a mouse model of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. J. Psychiatr. Res. 109, 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.11.021 (2019).

Zhang, J. et al. Discovery of anti-SARS-CoV-2 agents from commercially available flavor via Docking screening. Med. Plant. Biology. 2 (1). https://doi.org/10.48130/MPB-2023-0010 (2023).

Esmail, S. & Manolson, M. F. Advances in understanding N-glycosylation structure, function, and regulation in health and disease. European journal of cell biology, 100(7–8), 151186. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcb.2021.151186

Acknowledgements

The researchers supporting project number (RSP2025R494), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

The researchers supporting project number (RSP2025R494), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CALS, AAAM contributed to conceptualization; project administration and involved in supervision and in formal analysis; ARC was involved in investigation; ARC, LMB, and WH and JPK and AED contributed to methodology and writing—review and editing and contributed to writing—original draft; AA, MMA, MI, and A. Ali contributed to resources; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

dos Santos, C.A.L., de Araújo Monteiro, A.A., Costa, A.R. et al. ADME analysis, metabolic prediction, and molecular docking of lipoic acid with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron spike protein. Sci Rep 15, 24386 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93121-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93121-2