Abstract

Accurate estimates of the shear and Stoneley wave transit times are important for seismic analysis, rock mechanics, and reservoir characterization. These parameters are typically obtained from dipole shear sonic imager (DSI) logs and are instrumental in determining the mechanical properties of formations. However, DSI log may contain inconsistent and missing data caused by various factors, such as salt layers and spike phenomenon, which can cause difficulties in analyzing and interpreting log data. This study addresses these challenges and estimates the shear and Stoneley wave transit times in DSI Log using machine learning methods and common logs, including computed gamma ray (CGR), bulk density (RHOB), and compressional wave transit time (DTC), as well as depth-based lithology of different layers. Data from two wells in a field in southern Iran were used. Outliers and noise were carefully removed to improve data quality, and data normalization methods were implemented to ensure data integrity. Then, invalid DTC values were corrected and used to predict DTS and DTST. Finally, missing and invalid DSI Log values were predicted using the final models. Eight distinct machine learning models, such as Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting (GB), Support Vector Regression (SVR), Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Multivariate Polynomial Regression (MPR), CatBoost, LightGBM, and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), were independently trained and evaluated. The results show that Random Forest best predicted DSI Log parameters among all models. This approach facilitates subsurface interpretation and evaluation and provides a strong foundation for improving reservoir management and future decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Estimating the elastic properties and Stoneley wave transit times using log data is of great importance within the oil and gas sector as well as in geological exploration1. These parameters are essential for reservoir evaluation and characterization, as well as geomechanical modeling such as pore pressure prediction2. Shear wave transit times are used to determine geomechanical parameters such as Young's modulus and Poisson's ratio, which can assist in planning hydraulic operations and predicting reservoir behavior3. On the other hand, Stoneley waves are employed to estimate formation permeability and identify the types of fluids in the reservoir4. However, due to the high cost and operational constraints associated with well-logging tools, reliable and accurate shear wave transit time (DTS) and Stoneley wave transit time (DTST) measurements are challenging. DSI data can be unreliable due to a variety of factors, such as borehole conditions, instrument limitations, or data logging errors. For example, technological limitations in older wells that lack modern instrumentation can prevent DSI data from being recorded at certain depths in the well. In addition, high costs limit the use of advanced equipment. Various conditions, such as wellhead instability, also prevent data collection. Operational issues such as instrument failure or calibration errors, acoustic interference from drilling, and formation characteristics that absorb or scatter acoustic waves can also affect the accuracy of recorded data. The effect of fluids in the borehole, environmental factors such as temperature and pressure, acoustic properties of geological layers, and the design and sensitivity of the DSI instrument are some of the challenges that can lead to missing or unreliable DSI data. Missing or invalid DSI data can affect the quality and precision of result interpretation and analysis. Thus, it is crucial to provide an optimal method for predicting missing and invalid DSI data from conventional logs.

The development of machine learning algorithms has been introduced in innovative approaches to improve the precision and efficiency of predictive models. Early research in this domain primarily relied on traditional empirical relationships to predict DSI data. However, these conventional methods often fell short in delivering the required accuracy, particularly when dealing with complex geological formations. The advent of advanced machine learning techniques has since encouraged researchers to investigate the potential of artificial intelligence in this field. Numerous studies have explored the use of various machine learning methods to predict recorded parameters from DSI log data. Among these, one notable study proposed a methodology for estimating acoustic wave velocities using conventional well logs, leveraging artificial neural networks, fuzzy logic, and neurofuzzy algorithms. In order to improve the accuracy of these estimations, a hybrid model combining methods genetic algorithm (GA), particle swarm optimization (PSO) and adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system can also be used5,6.

Several studies have been conducted in this field so far. Onalo et al.3 introduced an exponential Gaussian process model that effectively predicts shear wave transit times in formations where reliable measurements are unavailable. This model serves as a dependable and economical tool for dynamic evaluation of oil and gas formations. The results of this research can enhance the understanding of shear transit times in areas lacking multipole sonic logs or where logging data has been compromised, particularly in the Niger Delta. This research is an introduction of an exponential Gaussian process model that effectively predicts shear wave transit times in formations where reliable measurements are unavailable. This model serves as a dependable and economical tool for dynamic evaluation of oil and gas formations. The results of this research can enhance the understanding of shear transit times in areas lacking multipole sonic logs or where logging data has been compromised, particularly in the Niger Delta. Another research that has been fulfilled by Ibrahim et al.7 is the advancement of machine learning models for predicting in-situ stresses from well-logging data demonstrates the versatility of these methods in various geophysical problems. This study seeks to employ various machine learning (ML) techniques, including random forest (RF), functional network (FN), and adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS), to predict the σh and σH using well-log data. A comparison of the results from the RF, ANFIS, and FN models for predicting minimum horizontal stress indicated that ANFIS performed better than the other two models. The findings of this study highlight the strong ability of machine learning to predict σh and σH using readily accessible logging data, without incurring additional costs or requiring site investigations. The generation of synthetic acoustic logs using five different machine-learning methods has also been investigated by Yu et al.8. In this study, the impact of machine learning in generating synthetic logs for various subsurface assessments has been investigated. Authers identified that data cleaning and clustering were essential for improving the performance across all models. In another research by Ahmed et al.9, supervised machine learning was used to forecast shear acoustic logs and petrophysical and elastic properties in the Kadanwari gas field and the practical applications of these methods in the real world have been investigated. To determine the optimal DTS log that aligns with the geological conditions, a comparison was conducted among three supervised machine learning (SML) algorithms: random forest (RF), decision tree regression (DTR), and support vector regression (SVR). According to qualitative statistical measures, the RF algorithm emerged as the most effective algorithm. Additionally, the RF algorithm was utilized for detailed reservoir characterization to generate elastic attributes from seismic and well data. These derived attributes enabled the establishment of a petro-elastic relationship at the reservoir level. Furthermore, Ibrahim et al.10 has applied decision tree and random forest algorithms to predict formation resistance, highlighting the versatility of machine learning methods in different facets of well-logging analysis. This paper focuses on estimating the true formation resistivity in complex carbonate sections by implementing decision tree (DT) and random forest (RF) machine learning techniques, using the existing well-logging data. The results indicate that machine learning can successfully fill gaps in log tracks and lower costs by removing the necessity for resistivity logs in all offset wells within the same field. Roy et al.11 has been carried out another investigation in the potential of using machine learning and artificial intelligence to replace sonic logs, particularly in areas where data may be absent or unreliable. These techniques can help predict sonic log data effectively. The research examines several widely used methods, including artificial neural networks, decision tree regression, random forest regression, support vector regression, and extreme gradient boosting, to assess their effectiveness and accuracy in predicting sonic transit times based on other well log information. The results indicate that, despite the popularity of artificial neural networks, both extreme gradient boosting and random forest regression actually provide better performance for this specific application. A comparative study also has been performed by Dehghani et al.12 to evaluate the effectiveness of various machine learning techniques in estimating shear wave transit time in a reservoir in southwestern Iran and examined the strengths and weaknesses of different machine learning approaches. The findings of this study identified the random forest method as the most suitable approach for estimating shear wave velocity. Several machine learning algorithms, including perceptron multilayer neural networks, Bayesian, Generalized least squares, multivariate linear regression, and support vector machine, were examined during the study. However, none of these methods exhibited superior performance compared to the random forest approach.

According to the conducted studies so far, mainly focused on shear wave transit time and Stoneley wave transit time has been less investigated. Investigating DTST along with other DSI Log parameters can provide a more comprehensive understanding of wave propagation in different geological formations and lead to improved drilling strategies and resource management. Therefore, in this research, different machine learning techniques are employed to estimate the missing and invalid shear wave transit time and Stoneley wave transit time. These considered machine learning algorithms are Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Regression (SVR), Gradient Boosting (GB), Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Multivariate Polynomial Regression (MPR), LightGBM, CatBoost, and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN). Also, The model performance is validated using the coefficient of determination (R2), mean squared error (MSE), and root mean squared error (RMSE).

In this paper, the second section provides detailed and complete explanations of the methodology. This section examines the data, the preprocessing steps, model selection, explanation of the algorithms used, the steps to build the final model, and the evaluation metrics. In third section, a detailed analysis of the model results is conducted, and comprehensive explanations are provided regarding the challenges and how to address them. Finally, forth section concludes discussion of the results and suggestions for future works.

Methodology

Data collection

To predict the shear wave transit time and Stoneley wave transit times, well-logging data obtained from two wells located in southern Iran, was utilized. The following parameters were selected from different logs and considered as input to the models:

-

Depth

-

Density (RHOB)

-

Computed Gamma Ray (CGR)

-

Compressional Wave Transit Time (DTC)

-

Lithology

-

Identified lithologies include anhydrite, salt, claystone, sandstone, argillaceous limestone, limestone, and marl.

The data is then processed and used as features in machine learning models to predict DTS and DTST values in dipole shear sonic imager logs.

Data preprocessing

Data preprocessing is essential to ensure data quality and validity. This process includes removing outliers and noise, managing missing data, and ensuring that each feature is within its correct range. The steps in data preprocessing are listed below:

-

1.

Removing outliers and noise: Outliers and noise in the data are identified and removed to prevent bias in the results. This step is crucial to maintain data integrity.

-

2.

Managing missing data: Due to the large size of the data bank, missing data are removed from the set so that the data bank with complete data is used for an initial analysis. One of the objectives of this paper is to predict missing values using developed machine learning models.

-

3.

Validating data ranges: The logical and correct range of each feature is examined and data outside the actual range is removed. This step helps identify invalid and incorrectly recorded data in the log.

Poisson's ratio concept was applied to ensure that the DTC and DTS logs have valid values. Poisson's ratio is a parameter between 0 and 0.5 for different materials. The value of Poisson's ratio was initially determined using Eqs. (1), (2), and (3).

where \(D{T}_{C}\), \(D{T}_{S}\), \({V}_{P}\), \({V}_{S}\), and \(\nu \), are compressional wave transit time, shear wave transit time, compressional wave velocity, shear wave velocity, and Poisson’s ratio, respectively.

As shown in Fig. 1, at some depths the Poisson's ratio calculated value was unrealistically low or negative. Therefore, considering the type of the rocks and based on the study of Gercek (2006)13, it was decided to consider the DTC and DTS data as missing at depths where the value of Poisson's ratio is below 0.15. These data were removed from the data bank to improve the overall quality and validity of the data. However, these removed data points were added to the missing values set to be eventually predicted.

By performing these steps, the data bank is ready for further analysis. Table 1 shows a summary of the pre-processed data set that was generated using the Python describe function. Computed gamma ray (CGR), bulk density (RHOB), compressional wave transit time (DTC), shear wave transit time (DTS) and identified lithologies such as anhydrite (Anhy), salt, claystone (Clst), sandstone (Sdst), argillaceous limestone (Argi_Lst), limestone (Lst), and marl (Ml) are presented based on depth. The table includes key statistical measures such as count, mean, standard deviation, minimum, 25th percentile, median (50th percentile), 75th percentile, and maximum values for each feature. By examining these measures, the average, variability, and overall distribution of the data can be observed. By applying pre-processing steps, including removing outliers, noise, and unreliable data, a clean and reliable data set has been created. This table is an essential reference for understanding the characteristics of the dataset and ensures that machine learning models are trained on valid and accurate data. Computed gamma ray (CGR), bulk density (RHOB), compressional wave transit time (DTC), and identified lithologies include anhydrite, salt, clay, sandstone, argillaceous limestone, limestone, and marl are presented based on depth.

Data normalization

Data normalization is a crucial preprocessing procedure in machine learning. It ensures that variables are on the same scale and prevents some features from dominating others during the model training. One common method for normalization is Min–Max scaling. In this method, each feature is placed in a range between 0 and 1. Using this method ensures that all features are placed on the same scale and the model’s performance is improved. This standardization process not only helps reduce potential biases in machine learning models but also increases the convergence and stability of the models.

Supervised machine learning

Supervised machine learning (ML) is commonly utilized in reservoir engineering to forecast and categorize various subsurface properties. The proposed method includes training a model on a labeled dataset, where the input data corresponds with the correct output. The model learns to associate inputs with outputs by minimizing the discrepancies between its predictions and actual values. In the context of DSI Log prediction, supervised machine learning can be employed to accurately assess the shear and Stoneley wave transit times, which are crucial for characterizing reservoir properties. By leveraging historical DSI data, these models can provide accurate and efficient solutions that improve decision-making processes and operational efficiency in reservoir management. The performance of supervised machine learning in this area helps with time management, enables working with large datasets, and leads to the discovery of patterns that traditional methods are unable to detect14.

Model selection

Choosing an appropriate candidate is a significant phase in machine learning, involving the evaluation and comparison of multiple algorithms to determine the most effective one for the given problem. For this purpose, different algorithms were trained on the same dataset, and their performance was carefully evaluated in both the training and validation stages. Comparing and evaluating models on training and test data allows for a thorough assessment of model performance and aids in the selection of the best model for the given problem15. In this study, eight machine learning algorithms were trained to select the best model. These algorithms include Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, Support Vector Regression, Multiple Linear Regression, Multivariate Polynomial Regression, LightGBM, CatBoost, and Artificial Neural Networks. Each algorithm was carefully evaluated and tested to ensure that the best model could be used to predict the current problem.

-

Random forest (RF) The RF algorithm performs well in regression problems due to its ensemble approach, which combines multiple decision trees to increase prediction accuracy. Each tree in the forest is constructed using a random subset of features, which helps reduce overfitting and improves generalizability. The proposed method is robust against noisy data and can handle large, high-dimensional datasets. In addition, random forests provide internal estimates of error and correlation, which are useful for evaluating model performance and the importance of variables, making them a powerful tool for solving regression problems16. Schematic of random forest algorithm is shown in Fig. 2.

-

Gradient boosting (GB) Gradient Boosting (GB) is a strong machine learning method employed for both regression and classification tasks. It constructs models sequentially, with each new model aiming to address the errors of previous ones by integrating the predictions of several weak learners, typically decision trees, to form a robust predictive model. The cost function is refined by adding new models that minimize the remaining errors of the combined set. Gradient boosting is recognized for its high precision and capability to manage diverse data types, making it a good choice for complex problems19. Structure of GB is presented in Fig. 3.

-

Support vector regression (SVR) Support Vector Regression (SVR) represents a type of Support Vector Machine (SVM) specifically used for regression analysis. Instead of aiming to minimize the observed training error, SVR emphasizes minimizing the bounded generalization error to enhance performance on unseen data. The fundamental idea is to compute a linear regression function within a high-dimensional feature space, where input data is transformed via a nonlinear function. This allows SVR to manage intricate, nonlinear relationships in data21. Figure 4 illustrates the SVR structure.

-

Multiple linear regression (MLR) Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) is a statistical methodology utilized to model the relationship between a dependent variable and several independent variables by fitting a linear equation to the observed data. MLR has been assessed for its effectiveness in correlating petrophysical properties with shear wave velocity concerning predicting shear wave velocity in the Asmari reservoir and has shown high potential in geophysical studies. The ability of this algorithm to identify and quantify the influence of different predictors on the target variable lies in its ability to make it a useful tool for deciphering datasets23. The simplicity and easy interpretability of MLR makes it a widely adopted machine learning method for regression tasks24.

-

Multivariate polynomial regression (MPR) Multiple Polynomial Regression is employed to model the connection between multiple independent variables and a dependent variable by fitting a polynomial equation to the data. MPR is effective in identifying intricate and nonlinear relationships among petrophysical properties such as porosity, shale volume, and permeability. This method extends the capabilities of linear regression by incorporating polynomial terms, thereby allowing more precise detection of the underlying data patterns. Using this approach, MPR can improve the predictive accuracy of permeability estimates, which is critical for reservoir characterization and decision-making in the oil and gas industry. However, the performance of MPR is highly dependent on how the data are preprocessed, including outlier removal and missing value management, to ensure model robustness and reliability25.

-

LightGBM The LightGBM machine learning algorithm is highly efficient and outperforms traditional methods in terms of memory usage and processing speed, this technique is efficient. This efficiency is achieved through two innovative methods: Gradient-based One-Side Sampling (GOSS) and Exclusive Feature Bundling (EFB). GOSS operates on data samples with larger partitions, as these samples play a key role in the information obtained from the model. EFB, conversely, decreases the number of features by combining individual ones. These optimizations make LightGBM excellent for large datasets with high features, allowing for faster training and increased accuracy19. LightGBM differs from other gradient boosting methods by growing tree leaf-wise instead of level-wise. This means it chooses the leaf with the largest potential reduction in loss to split, leading to potentially smaller and more efficient trees for a given maximum depth compared to level-wise approaches. Figure 5 visually explains how LightGBM, using techniques like GOSS, EFB, and its leaf-wise splitting strategy, works26.

-

CatBoost The gradient boosting library is designed to reduce prediction variance during training when the model predictions for training examples differ from the test examples. This is achieved by using a sequence of baseline models that removes the current example from its training set to provide more accurate gradient estimates. The proposed method also efficiently manages classification features by converting them into numerical values that represent the expected target value for each class using a method that prevents overfitting. In addition, CatBoost uses symmetric trees that grow all leaf nodes simultaneously under the same split conditions, which increases the stability and performance of the model. These features make CatBoost a suitable machine-learning model for various problems. In this study, CatBoostRegressor was applied to a regression problem involving well-logging data19. Structure of CatBoost algorithm is presented in Fig. 6.

-

Artificial neural networks (ANN) Artificial neural networks are computational systems modeled after the structure and functionality of the human brain. They consist of neurons arranged in layers, where each neuron processes input data and transmits its output to the subsequent layer. These networks can learn intricate patterns and relationships through a process called training, in which the network adjusts its weight based on the prediction error. The ability of ANNs to model nonlinear relationships and learn from large datasets has made them a cornerstone of modern artificial intelligence28. Figure 7 shows the structure of the ANN model.

The architecture of Gradient Boosting Decision Tree20.

Structure of support vector regression model22.

Leaf-wise tree in LightGBM algorithm26.

Structure of CatBoost algorithm27.

General structure of ANN model29.

Hyper-parameter tuning

To identify the optimal value of the hyperparameters, a specific search space is considered for each parameter. In this study, a grid search was performed for each model training scenario utilizing the GridSearchCV function from the scikit-learn library, which applies the range of values listed in Table 2. The grid search process evaluates all possible combinations in the search space. Despite its high computational intensity, grid search is the most common method for optimizing hyperparameters and leads to finding the best values for the hyperparameters among all possible cases.

Stacked machine learning models

Model stacking involves combining predictions from multiple models to generate a final model. This approach employs a single model to learn from the predictions made by prior models. By leveraging the strengths of different models, a stacked stack can provide more reliable and accurate results than a single model. The proposed method selects and merges the best models at runtime and optimizes them by the nature of the data and the specific target problem. The advantages of stacked modeling include increased predictive power, reduced overfitting, and improved generalizability to new data. Given the complexity of data in the oil and gas industry, these models are better suited for predicting petrophysical properties and well-logging data for reservoir characterization30.

To overcome the problems associated with DTC data, a stack model is built. Initially, the depth, RHOB, CGR, and lithology of each layer are used to predict invalid DTC values. For this purpose, various machine learning algorithms, including Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting (GB), Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Support Vector Regression (SVR), and Multivariate Polynomial Regression (MPR) were used. The next step involves predicting the shear-wave transit time (DTS). In this step, these five models are investigated and evaluated. The final stack model is constructed using the best-performing algorithms. Simultaneously, another stack model was developed to predict the Stoneley wave transit time (DTST). For DTST prediction, the artificial neural networks (ANN), CatBoost, LightGBM, and Random Forest (RF) algorithms were evaluated.

Building models and predicting data

After selecting the model, the next step involves performance testing, validation, and development of the model to estimate missing and invalid values in the dataset. This process involves several steps:

-

I.

Development of the DTC model

-

•

Model selection: A range of machine learning algorithms, including Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting (GB), Support Vector Regression (SVR), and Multivariate Polynomial Regression (MPR), were used to predict DTC. These models used depth, CGR, RHOB, and lithology as input features to increase the prediction accuracy.

-

•

Model training and validation: The models were trained using the correct DTC data. The models were then evaluated using cross-validation.

-

•

Prediction: The Random Forest (RF) model was selected due to its better performance than the other algorithms. After evaluating and validating its performance, the RF model was used to predict missing and invalid DTC values.

-

II.

Development of the DTS model

-

•

Model selection: Multiple models, including random forest (RF), support vector regression (SVR), multiple linear regression (MLR), multivariate polynomial regression (MPR), and gradient boosting (GB), were investigated for predicting the shear wave transit time (DTS).

-

•

Model training and validation: These models were trained using depth, RHOB, CGR, DTC (predicted values from the RF model along with previous correct values available in the log data), and lithology. These models were evaluated using various evaluation criteria to select the best model for predicting DTS.

-

III.

Development of DTST model

-

•

Adding the DTST data: In this step, the Stoneley wave transit time data is added to the original dataset. This requires preprocessing the new data to handle outliers, noise, and missing values in the DTST data. Outliers and noise are removed, and missing values are removed from the database to ensure data integrity and quality. Table 3 provides a statistical overview of the data utilized for the DTST model after re-preprocessing.

-

•

Model selection: Models such as Random Forest (RF), LightGBM, CatBoost, and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) were used to predict DTST.

-

•

Model training and validation: The models were trained using depth, RHOB, CGR, DTC, and lithology as input features. Finally, the models were validated and tested to ensure their accuracy and reliability in predicting the DTST.

-

IV

Choosing Random Forest as the final model

After conducting the evaluations and examining the performance of various algorithms such as Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting (GB), Support Vector Regression (SVR), Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Multivariate Polynomial Regression (MPR), CatBoost, LightGBM, and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), it has been determined that the Random Forest algorithm is the most effective algorithm in this problem. The reasons for selecting the RF algorithm as the final model for predicting DSI log parameters are mentioned in the following:

-

1.

High capability in handling complex data and non-linear relationships: DSI logs, along with other conventional logs, record complex geological data with non-linear relationships. Unlike simple linear models, Random Forest can capture these non-linear relationships without requiring explicit feature engineering or pre-defined functional forms. This is critical for accurate prediction of transit time in geologically heterogeneous formations.

-

2.

Robustness to overfitting: Advanced models such as ANN have the ability to capture highly complex relationships within data. However, they are prone to overfitting, especially when trained on limited datasets. Random Forest mitigates overfitting by generating multiple decision trees and combining their results due to its ensemble approach. This ensures that the model performs well on new, unseen data, which is a significant advantage compared to neural networks, which are prone to overfitting.

-

3.

Handling missing data and outliers: DSI logs often contain missing data, outliers, and noisy measurements due to borehole conditions, tool malfunctions, or geological complexities. Random Forest is relatively robust to these issues. The ensemble nature of the RF makes it less sensitive to outliers in the training data, as individual outliers have less influence on the overall prediction.

-

4.

Computationally efficient and suitable for large datasets: Compared to some other complex methods, Random Forest offers a good balance between accuracy and computational cost. Training and prediction with RF can be relatively fast, even with large DSI log datasets. This is particularly important for processing large well-log data across multiple wells or geological intervals. Although ANNs might offer slightly better predictive power in some cases, the computational cost associated with training deep neural networks can be significant, especially when hyperparameter tuning is required.

-

V.

Predict missing and invalid data:

-

•

Sequential Prediction Process: After developing and validating the models, the final step involves predicting missing and invalid values for DTC, DTS, and DTST. The RF model was first used to predict DTC values. These predicted DTC values, with the correct values from the well-log data as input along with other features, are used to predict the DTS and DTST values using the corresponding models developed in the previous steps.

-

•

Data Quality: This sequential prediction approach ensures that all missing and invalid values are accounted for, resulting in a high-quality dataset for future analyses.

This structured approach ensured that the dataset was comprehensive and accurate, enabling reliable predictions and proper analysis of the log data. Figure 8 shows the overall process of building and developing stacked machine learning models.

Evaluation metrics

Evaluation criteria, including coefficient of determination (R2), mean squared error (MSE), and root mean squared error (RMSE), were used to evaluate the performance of the models.

where \({y}_{i}\) is the actual value (DTC, DTS, DTST), \(\widehat{{y}_{i}}\) is the predicted value (DTC, DTS, DTST), \(\overline{{y }_{i}}\) is the arithmetic mean, and n is the number of observations of the variables.

In addition, basic rock properties including Poisson's ratio and Young's dynamic modulus, were calculated to ensure that the results were within acceptable and accurate limits. The Young modulus formula was used to evaluate the final prediction results. The above formula is essential for evaluating the elastic properties of the studied materials. Young's modulus is defined as

where \(\rho \) is Density and \({E}_{d}\) is the Dynamic Young's modulus.

Results and discussions

The application of machine learning algorithms for forecasting the shear and Stoneley wave transit times yielded acceptable and reliable results, indicating the potential of these methods for improving subsurface characterization and reservoir evaluation. The integration of conventional well logging data, such as computed gamma ray data, bulk density, compressional wave transit time, and lithology, provides a comprehensive dataset for training and validating models. The data preprocessing and data management steps, especially in the invalid parts of the DSI Log, create valid and reliable datasets. Among the evaluated machine learning models, the random forest algorithm demonstrated the best performance and effectively predicted and completed missing and invalid values in the DSI Log. In the following, the models' results and performance are assessed based on different criteria, and the implications of using machine learning methods in decision-making and reservoir management processes are examined.

Evaluation of machine learning model performance

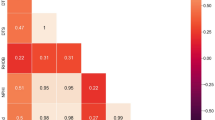

In this research, a total of eight machine-learning models were employed to analyze data from two wells located in southern Iran, under 3 scenarios. For the initial assessment of these models' performance, the train-test split method was implemented. In total, 11,218 data were analyzed and evaluated. The dataset was allocated to 80% for training and 20% for testing. For predicting the compressional wave transit time, the random forest (RF), Gradient Boosting (GB), Multivariate Polynomial Regression (MPR), and Support Vector Regression (SVR) algorithms were investigated. The models utilized for predicting the shear-wave transit time, the models included RF, GB, MPR, SVR, and MLR. In addition, RF, CatBoost, LightGBM, and ANN models were used to predict the Stoneley wave transit time. The evaluation of these models' performance was conducted using various metrics, including the coefficient of determination (R2), mean squared error (MSE), and root mean squared error (RMSE). The results presented in Table 4 indicate that the random forest model consistently outperformed the other models and had the highest accuracy and lowest error in both training and testing data.

Figure 3 shows the performances of different machine learning algorithms in predicting the compressional-wave transit time. As shown in Fig. 3, the actual DTC values are plotted against the predicted values for the test data for all models. The R2 values and the 45-degree line (x = y line), which represent the best model performance, are also displayed for each algorithm. Among the algorithms, SVR, which had a lower R2 value and a larger deviation from the 45° line, performed the worst. In contrast, the RF and GB algorithms, with high R2 values and very low deviation from the 45° line, performed the best.

Figure 4 shows the results of shear wave transit time prediction using random forest, gradient boosting, multivariate polynomial regression, support vector regression, and multivariate linear regression. Similar to Fig. 3, this plot shows the actual DTS values versus the predicted values in the test data, a 45° line, and the R2 values for each model. In this case, multivariate linear regression showed the weakest performance, with the lowest R2 value and significant deviations from the 45° line. Similarly, the RF and GB models outperformed the other models, providing reliable predictions with high R2 values.

Figure 5 indicates the performance of Stoneley wave transit time prediction using the RF, CatBoost, LightGBM, and ANN algorithms. The graph follows the same pattern as the previous one and displays the actual vs. predicted DTST values, a 45° line, and R2 values. Among these models, the ANN model exhibited the poorest performance, with a lower R2 value and more scatter around the 45° line. RF and CatBoost emerged as the best models and provided the most reliable predictions with the highest R2 values.

Overall, the comparative analysis in Figs. 9, 10, and 11 shows that the RF model followed by the GB model yielded the best performances in predicting DTC, DTS, and DTST. These findings emphasize the robustness and accuracy of the RF and GB in handling complex well-log data for subsurface characterization and reservoir evaluation.

Figures 12, 13, and 14 show bar graphs comparing different machine learning algorithms based on the R2 evaluation criterion on the training and testing data. The Figures show that the RF, GB, and Catboost algorithms maintain good accuracy across the training and testing datasets, indicating the robustness and reliability of their predictions. In contrast, the SVR, MLR, and ANN algorithms showed a significant decrease in performance, which could indicate the problems of overfitting and non-generalizability of the models.

Based on the initial evaluation results, the random forest algorithm demonstrated the best performance in all stages of the machine learning models for predicting DTC, DTS, and DTST. Consequently, the random forest model was selected to create the final model. At this stage, 90% of the dataset was allocated for training, while 10% was set aside for validation (development set) to confirm the reliability of the model's performance. After creating the development set, a test set (blind test) was created independently and without separating the data into training and testing sets in Python. The blind test set differs from the validation set. The validation set was used during the model training process to adjust the hyper-parameters to prevent overfitting and offer an impartial evaluation of the model's effectiveness on the training dataset. In contrast, the blind test set was used after training and validation of the model to evaluate its performance on an unseen dataset, ensuring the generalizability and robustness of the model. The findings from this evaluation are shown in Table 5.

The results of the development set are presented in three separate graphs to evaluate the model’s performance in predicting DTC, DTS, and DTST. These graphs offer a detailed visual representation of the model’s accuracy and performance while also highlighting areas that need enhancement. Figures 15, 16, and 17 show scatter plots for the random forest model, comparing the actual values with the predicted values for DTC, DTS, and DTST in the development set.

Figures 18, 19, and 20 show scatter plots for the blind test results of the random forest model, comparing the actual values with the predicted values of DTC, DTS, and DTST. These plots comprehensively represent the accuracy and performance of the model on unseen data.

Validation and review of results using rock mechanics parameters

To validate the model performance in real-life problems, rock mechanic parameters, such as Poisson's ratio and Young's modulus, were calculated and analyzed for the predicted values. The results show that Poisson's ratio and Young's modulus for the predicted values from the models are within the correct ranges and that the models perform well in real-world scenarios.

Predict missing and invalid data in the DSI Log

The final step uses the random forest model to predict missing and invalid data in the DSI Log. The results of the final random forest models demonstrate good performance for the stacked machine learning models. The results of the final models for the DTC, DTS, and DTST data are shown in Figs. 21, 22, and 23, respectively, which demonstrate the accuracy and validity of the predicted values.

Discussions

The findings and results show that the Random Forest and Gradient Boosting algorithms perform effectively in predicting the shear and Stoneley wave transit times. These two algorithms consistently showed the highest accuracy at all stages of prediction. The RF model's performance in managing complex features and its robustness against overfitting contributed significantly to its superior performance. However, it is important to point out that relying on R2 or other evaluation criteria is not sufficient for practical and experimental applications in the real world. In the present problem, the initial results of the model yielded high and promising R2 values; however, inconsistencies were identified through various rock mechanics analyses and interpretations, such as Poisson's ratio and Young's modulus, which led to the identification of problematic and invalid data in the dataset. These findings emphasize that reliance on conventional evaluation criteria, such as R2, MSE, RMSE, etc. alone is not sufficient and will cause problems when solving real problems.

In the oil and gas industry, conducting thorough data reviews and analyses with the support of experts and using specialized tools is of great importance. This approach ensures that the models not only perform well in theoretical evaluations but also provide reliable and accurate predictions in practical and experimental scenarios. The sequential prediction approach, in which erroneous and invalid DTC values are predicted and then used as input to the models to predict DTS and DTST, has effectively helped solve the existing problems. The proposed method has increased the overall quality and validity of the training dataset, leading to accurate predictions and robust analysis.

This study demonstrated the power of machine learning algorithms in predicting DTC, DTS, and DTST in DSI Log. The results highlight the significance of choosing appropriate models and applying data preprocessing methods to ensure model performance. Future research could explore further features in advancing rock mechanics studies by validating novel machine learning methods and assessing the performance of models in real-world scenarios.

Conclusions

This study investigates the efficiency and performance of various machine learning algorithms in predicting the transit times of shear and Stoneley waves in DSI Log. For this purpose, common well logging data, such as computed gamma ray data, bulk density, compressional wave transit time, and lithology, are used as model inputs. Data preprocessing steps include removing outliers, handling missing data, and ensuring data accuracy and validity (with special attention to the problems related to DTC data). The model-building process involves developing several models for predicting DTC, including random forest, gradient boosting, multivariate polynomial regression, and support vector regression. DTS values are estimated by several models, including RF, SVR, MLR, MPR, and GB. In addition, to predict DTST, re-processing was performed on new data, and predictions were made using RF, LightGBM, CatBoost, and ANN. The results demonstrate that the random forest algorithm consistently performs best and provides acceptable and reliable results for complex problems. By using stacked machine learning models for sequential prediction, missing or inconsistent values can be corrected, especially in the salt layers. This creates a full, reliable, and integrated dataset in the DSI Log. The findings show that the use of machine learning methods to estimate DTS from conventional logs is feasible and can be an alternative to expensive DSI logging in some cases. This approach demonstrates the high potential of machine learning methods for improving reservoir characterization and enhancing decision-making processes in the oil and gas industry. Additionally, it enhances the reliability and accuracy of data recorded during logging. Finally, future work may explore its applications in improving reservoir characterization and advancing rock mechanics studies.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Iranian Offshore Oil Company (IOOC) but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of IOOC. Consequently, researchers who need the study's data can reach out to the corresponding author. The corresponding author will then obtain permission from the IOOC to share the data.

References

Ahmed, N., Weibull, W. W. & Grana, D. Constrained non-linear AVO inversion based on the adjoint-state optimization. Comput. Geosci. 168, 105214 (2022).

Ahmed, N., Weibull, W. W., Grana, D. & Bhakta, T. Constrained nonlinear amplitude-variation-with-offset inversion for reservoir dynamic changes estimation from time-lapse seismic data. Geophysics 89(1), R1–R15 (2024).

Onalo, D. et al. Data-driven model for shear wave transit time prediction for formation evaluation. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 10(4), 1429–1447 (2020).

Rostami, A. et al. New insights into permeability determination by coupling Stoneley wave propagation and conventional petrophysical logs in carbonate oil reservoirs. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 11618 (2022).

Asoodeh, M. & Bagheripour, P. Prediction of compressional, shear, and Stoneley wave velocities from conventional well log data using a committee machine with intelligent systems. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 45, 45–63 (2011).

Zahmatkesh, I. et al. Estimation of DSI log parameters from conventional well log data using a hybrid particle swarm optimization–adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 157, 842–859 (2017).

Ibrahim, A. F., Gowida, A., Ali, A. & Elkatatny, S. Machine learning application to predict in-situ stresses from logging data. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 23445 (2021).

Yu, Y. et al. Synthetic sonic log generation with machine learning: a contest summary from five methods. Petrophysics 62, 393–406 (2021).

Ahmed, S., MonaLisa, Hussain, M. & Khan, Z. Supervised machine learning for predicting shear sonic log (DTS) and volumes of petrophysical and elastic attributes, Kadanwari Gas Field, Pakistan. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 9191 (2022).

Ibrahim, A. F., Abdelaal, A. & Elkatatny, S. Formation resistivity prediction using decision tree and random forest. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 47(9), 12183–12191 (2022).

Roy, V. et al. Augmenting and eliminating the use of sonic logs using artificial intelligence: A comparative evaluation. Geophys. Prospect. 71, 1933–1950 (2022).

Dehghani, M., Jahani, S. & Ranjbar, A. Comparing the performance of machine learning methods in estimating the shear wave transit time in one of the reservoirs in southwest of Iran. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 4744 (2024).

Gercek, H. Poisson’s ratio values for rocks. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 44(1), 1–13 (2007).

Zhou, W. et al. Machine learning in reservoir engineering: A review. Processes 12, 1219. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12061219 (2024).

Rezaee, R. & Ekundayo, J. Permeability prediction using machine learning methods for the CO2 injectivity of the precipice sandstone in Surat Basin, Australia. Energies 15, 2053. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15062053 (2022).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45(1), 5–32 (2001).

Verikas, A., Gelzinis, A. & Bacauskiene, M. Mining data with random forests: A survey and results of new tests. Pattern Recognit. 44(2), 330–349 (2011).

Verikas, A. et al. Electromyographic patterns during golf swing: activation sequence profiling and prediction of shot effectiveness. Sensors 16(4), 592 (2016).

Bentéjac, C., Csörgő, A. & Martínez-Muñoz, G. A comparative analysis of gradient boosting algorithms. Artif. Intell. Rev. 54(3), 1937–1967 (2021).

Deng, H., Zhou, Y., Wang, L. & Zhang, C. Ensemble learning for the early prediction of neonatal jaundice with genetic features. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 21, 1 (2021).

Basak, D., Pal, S. & Patranabis, D. Support vector regression. Neural Inf. Process. Lett. Rev. 11, 203–224 (2007).

Chen, Y., Yang, S., Yongfeng, S. & Zheng, M. Ship track prediction based on DLGWO-SVR. Sci. Program. 2021, 1–14 (2021).

Akhundi, H., Ghafoori, M. & Lashkaripour, G. R. Prediction of shear wave velocity using artificial neural network technique, multiple regression and petrophysical data: A case study in Asmari Reservoir (SW Iran). Open J. Geol. 04, 303–313 (2014).

Maulud, D. & Abdulazeez, A. A review on linear regression comprehensive in machine learning. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. Trends 1, 140–147 (2020).

Khilrani, N., Prajapati, P. & Patidar, A. K. Contrasting machine learning regression algorithms used for the estimation of permeability from well log data. Arab. J. Geosci. 14(20), 2070 (2021).

Paul, D., Moridpour, S., Venkatesan, S. & Withanagamage, N. Evaluating the pedestrian level of service for varying trip purposes using machine learning algorithms. Sci. Rep. 14, 1 (2024).

Paul, S., Das, P., Kashem, A. & Islam, N. Sustainable of rice husk ash concrete compressive strength prediction utilizing artificial intelligence techniques. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 25, 1–16 (2023).

Montesinos López, O. A., Montesinos López, A. & Crossa, J. Fundamentals of artificial neural networks and deep learning. In Multivariate Statistical Machine Learning Methods for Genomic Prediction (eds Montesinos López, O. A. et al.) 379–425 (Springer, 2022).

Yao, P., Yu, Z., Zhang, Y. & Xu, T. Application of machine learning in carbon capture and storage: An in-depth insight from the perspective of geoscience. Fuel 333, 126296 (2023).

Saikia, P. & Baruah, R. D. Stacked ensemble model for reservoir characterisation to predict log properties from seismic signals. Comput. Geosci. 27(6), 1067–1086 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to appreciate the Iranian Science Foundation. Also the authors would like to appreciate Iranian Offshore Oil Company for providing the raw data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mohammadkazem Amiri generated the original idea for the paper. Donya Amerian, Mohammadkazem Amiri, and Ali Safaei developed the machine-learning models and wrote the main manuscript text. Masoud Riazi, Amoussou Adoko, and Mehdi Veiskarami provided advice and guidance during the project, prepared the table, and figures and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statements

We confirm that this work is original and has not been published elsewhere, nor is it currently under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amerian, D., Amiri, M., Safaei, A. et al. Stacked machine learning models for accurate estimation of shear and Stoneley wave transit times in DSI log. Sci Rep 15, 8821 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93730-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93730-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Hybrid Deep Learning Frameworks for Predicting Shear Wave Velocity and Young’s Modulus from Well Log Data

Geotechnical and Geological Engineering (2026)