Abstract

Data imbalance is a critical factor affecting the predictive accuracy in collision risk assessment. This study proposes an advanced active generative oversampling method based on Query by Committee (QBC) and Auxiliary Classifier Generative Adversarial Network (ACGAN), integrated with the Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network (WGAN) framework. Our method selectively enriches minority class samples through QBC and diversity metrics to enhance the diversity of sample generation, thereby improving the performance of fault classification algorithms. By equating the labels of selected samples to those of real samples, we increase the accuracy of the discriminator, forcing the generator to produce more diverse outputs, which is expected to improve classification results. We also propose a method for dynamically adjusting the training epochs of the generator and discriminator based on loss differences to achieve balance in model training. Empirical analysis on four publicly available imbalanced datasets shows that our method outperforms existing methods in terms of precision, recall, F-measure, and G-mean. Specifically, our method’s results are above 0.92 on all evaluation indicators, with an average improvement of 23–28.3% compared to the worst-performing ENN method. This indicates that our method has a significant advantage in handling data imbalance, being able to more accurately identify collision samples and reduce the misclassification rate of non-collision samples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Within the ambit of contemporary societal operations, collision risk prediction is an integral aspect of diverse sectors, encompassing traffic safety and industrial activity. The imperative of accurately forecasting potential collision risks is paramount, as it directly pertains to the preservation of human life and the safeguarding of material assets1,2,3. The efficacy of these predictions is crucial for informed decision-making and the promptness of emergency measures. Furthermore, adept prediction models significantly contribute to diminishing incident frequencies, optimizing operational productivity, and prudent allocation of resources, thereby exerting a beneficial influence on both quotidian activities and industrial practices.

The construction of robust collision risk prediction models necessitates addressing the challenge of data imbalance—a prevalent issue wherein the frequency of non-collision instances eclipses that of collision events, thus skewing the dataset4,5. This imbalance poses substantial obstacles for standard machine learning and deep learning paradigms. The term fault imbalance refers to the situation where the distribution of samples across different classes is skewed, leading to an overrepresentation of certain classes (majority classes) and an underrepresentation of others (minority classes). This imbalance can significantly affect the performance of machine learning models, as they tend to be biased towards the majority class, resulting in poor predictive accuracy for the minority class. Thus, the presence of data imbalance significantly affects the predictive accuracy and generalizability of models, similar to findings in some clinical studies6.

To address this challenge, the focus has turned to Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), a novel type of network composed of a generator and a discriminator that synthesize realistic-looking data and distinguish between genuine and artificial samples through an inherent adversarial mechanism7,8. GANs show potential in improving model predictive accuracy for the minority class in the field of collision risk prediction by enhancing the representation of the minority class.

Despite the promise of GANs in handling imbalanced datasets, they suffer from instability during training and a lack of diversity in the generated samples. To overcome these issues, a new active generative oversampling method is proposed in this study, based on Query by Committee (QBC) and Auxiliary Classifier Generative Adversarial Network (ACGAN), integrated with the Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network (WGAN) framework. The purpose of this method is to enhance the diversity of sample generation and improve the performance of fault classification algorithms by selectively enriching the minority class samples through QBC and diversity metrics. In the context of imbalanced datasets, minority class samples refer to the instances of the class that is underrepresented compared to other classes. For example, in collision risk prediction, collision events are typically rare and thus form the minority class, while non-collision events are more frequent and form the majority class. Addressing the imbalance between these classes is critical for improving the predictive accuracy of models. Additionally, by equating the labels of selected samples to those of real samples, the accuracy of the discriminator is increased, forcing the generator to produce more diverse outputs, which is anticipated to improve classification results.

The aim of this study is to provide a more robust and accurate collision risk prediction model to tackle data imbalance issues in the real world. The primary reason for employing our proposed active generative oversampling methodology, based on QBC and the Wasserstein Auxiliary Classifier Generative Adversarial Network (W_ACGAN), is its specific design to effectively address the challenges posed by data imbalance in collision risk prediction. Unlike many traditional machine learning methods, our approach focuses on enhancing the diversity and quality of generated samples, which is critical in applications where collision events are rare. This tailored strategy allows us to improve the representation of minority classes, leading to more accurate predictions. Furthermore, while other novel machine learning techniques may show promise in various contexts, they often do not adequately tackle the unique issues presented by imbalanced datasets in collision risk scenarios. Our methodology not only integrates active learning principles but also leverages the stability of the Wasserstein distance, making it particularly suitable for the challenges identified in our research.

Main contributions of the proposed methodology:

-

(1)

Enhanced diversity in sample generation: Our proposed active generative oversampling methodology, which combines QBC and the W_ACGAN, is specifically designed to produce more diverse and high-quality samples. This is crucial for improving the representation of minority classes in collision risk prediction.

-

(2)

Improved stability and performance: By employing the Wasserstein distance, our framework enhances training stability and the quality of generated samples, mitigating common issues faced by traditional GANs.

-

(3)

Tailored approach for collision risk prediction: Our methodology addresses the unique challenges associated with imbalanced datasets in the context of collision risk prediction, offering a novel solution that has demonstrated superiority over existing methods in empirical evaluations.

State of the Art

The prediction of collision risk can be viewed as a classification problem, where the pre-collision state is used as the positive sample for the classification problem and the normal condition as the negative sample. In reality, collisions are rare and conflicts are relatively infrequent, so there are far more normal conditions available than pre-collision situations, which creates an imbalance of positive and negative samples. The sample class imbalance problem is an inevitable problem in existing collision prediction models, and how to deal with this problem is also regarded as one of the most critical steps in the modeling process. This study mainly focuses on the data level and develops the discussion from three aspects: under-sampling, over-sampling, and mixed sampling. The structures of their unbalanced classification models are shown in Figs. 1, 2 and 3.

Current status of undersampling algorithms

In this chapter, undersampling algorithms are divided into nearest neighbor-based undersampling algorithms, clustering-based undersampling algorithms, SVM-based undersampling algorithms, and integration-based undersampling algorithms based on the basic ideas.

(1) Nearest neighbor under-sampling algorithm.

Near-neighbor-based undersampling algorithms are more common. This type of undersampling method mainly relies on the nearest neighbors of each sample for undersampling, and the main feature is that the nearest neighbors of each sample need to be found first. For example, Li and Dai et al.9 proposed Condensed Nearest Neighbour (CNN), which uses 1-nearest neighbor to remove majority class samples whose 1-nearest neighbor is a minority class sample. Swana et al.10 proposed an adaptive Tomeklink undersampling method to undersampling majority class samples to alleviate class overlap and imbalance. To alleviate the class overlap and imbalance problems. Balla et al.11 proposed the OSS (one-sided selection) algorithm based on TomekLink pairs, drawing on the idea of CNN. The ENN (Edited Nearest Neighbours)12 algorithm analyzes the k-nearest neighbors of each sample in the majority class samples. If there are more samples in the minority class than in the majority class, then the majority class is deleted. NCL (Neighborhood Cleaning Rule)13 extends the ENN algorithm to delete only the majority class samples and analyzes the k-nearest neighbors of each sample in the minority class. CNNTL (Condensed Nearest Neighbor + TomekLink)14 addresses the problem of high time spent on calculating TomekLink pairs in the OSS algorithm by first finding a consistent subset of the dataset, and then using 1NN and TomekLink pairs for the under-sampling operation, which greatly reduces the time complexity.

(2) Clustering-based undersampling algorithm.

Clustering-based undersampling algorithms refer to the undersampling operation based on clustering. For example, Onan et al.15 combine clustering and undersampling techniques to balance the dataset by undersampling most of the class samples on the basis of clustering. Similar approaches are CPM (Class Purity Maximization)16, SBC (Undersampling Based on Clustering)17, etc.

(3) SVM-based undersampling algorithm.

SVM is a classification model based on classification decision boundary, where the learned classification hyperplane is only related to the support vectors located near the classification hyperplane. Therefore, it is feasible for decision boundary-based classifiers to undersample the dataset by using SVM as a pre-processor for the unbalanced dataset. There have been researchers who have conducted studies in this area, mainly focusing on misclassified samples and boundary samples. For example, Kobat et al.18 used a pre-trained SVM to pre-process the unbalanced data by dividing the misclassified samples in the majority class into minority classes. The results show that the prediction correctness of the minority class samples is improved without affecting the overall accuracy. Wang et al.19 first use the random forest to screen the dataset with features, and after feature screening builds an SVM to pre-process the dataset, and similarly divide the misclassified samples from the majority class into the minority class.

(4) Integration-based undersampling algorithm.

With the popularity of the integration idea, in recent years, some people also integrate the idea of integration into the undersampling algorithm and propose an integration-based undersampling algorithm. For example, Gao et al.20 undersampling algorithm only select a subset of the original dataset of the problem, and proposed two integration methods BalanceCascade and EasyEnsemble, which dramatically improves the performance of unbalanced data classification.

State of the art of oversampling algorithm research

The oversampling algorithms are categorized into three groups: SMOTE and its variants, generative adversarial networks, and oversampling algorithms based on other methods.

(1) SMOTE and its variants.

SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) is one of the classical oversampling algorithms21. After the SMOTE algorithm was proposed, researchers proposed many classical algorithms on the basis of SMOTE, such as the borderline-based SMOTE variant Borderline SMOTE22 and Safe Level SMOTE based on safety level23, etc. Halim et al.24 proposed another improved algorithm based on SMOTE, namely ADASYN. The main principle of this algorithm is to decide the number of samples to be generated based on the distribution of the data in the original dataset.

(2) Generative Adversarial Network.

GAN is a new data generation method proposed by Goodfellow et al.25. The overall distribution of the dataset is first acquired and then the data is generated based on the overall distribution. With the application of GANs in image and text domains, some scholars have also started to use GANs to deal with imbalanced classification problems. For example, Ahsan et al.26 proposed an outlier detectable generative adversarial network (OD-GAN) oversampling algorithm for the unbalanced data and majority class sample outlier problem. While generating the minority class samples, the majority class sample outliers are removed based on the majority class sample output values in the generator. Tang et al.27 proposed a new Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) to generate new samples to expand the banknote dataset, and used this dataset to train a banknote amount recognition framework.

(3) Oversampling algorithms based on other methods.

In addition to SMOTE and its variants, scholars have studied some new oversampling algorithms by drawing on some other methods. For example, the SPIDER228 algorithm first divides the samples whether they are easily misclassified or not, and then performs the oversampling operation on the divided dataset. Zhang et al.29 proposed the radial-based oversampling (RBO) algorithm. This algorithm finds the region where the minority class synthetic target should be generated based on the estimation of the imbalance distribution using radial basis functions. Huang et al.30 combined feature selection methods with oversampling techniques to improve the prediction accuracy of minority class samples.

Current research status of hybrid sampling algorithms

In addition to the under/over-sampling used classical methods, research workers have proposed some new hybrid sampling ideas. For example, Karthikeyan et al.31 proposed the SMOTE RSB algorithm that combines SMOTE and a rough set for the unbalanced data classification problem. Devi et al.32 proposed a hybrid sampling algorithm that uses SMOTE for oversampling and particle swarm optimization algorithm for undersampling, which is very effective in the field of malicious website identification. In addition, Merdas et al.33 proposed an EMS (Elastic Net - MLP - SMOTE) model. The model utilizes two machine learning algorithms and uses the SMOTE to predict the occurrence of stroke. Deng et al.34 put forward a SMOTE-FRS method for predicting and trading the movement of futures. This method solves the problem of sample imbalance. It is an effective tool to analyze complex nonlinear information with high noise and uncertainty in financial time series. Pratap et al.15 proposed a method that combines K-means clustering with Tomek links to identify and retain the most informative samples from the majority class. This approach helps to reduce the impact of class imbalance by focusing on the most representative instances.

Current works in imbalanced data classification offer a variety of techniques, including undersampling, oversampling, and hybrid sampling methods, which provide flexibility depending on the specific characteristics of the dataset at hand. However, due to the generation of synthetic samples, these models are prone to overfitting. And when the class distribution is complex or clustering algorithms cannot capture it well, these methods may not achieve optimal performance. The proposed method leverages the generative capabilities of the W_ACGAN framework, which is more sophisticated than traditional SMOTE in generating synthetic samples. It can produce a richer and more diverse set of samples that better represent the minority class. By integrating QBC and diversity metrics, the proposed method selectively enriches the minority class samples, enhancing the diversity of sample generation and improving the performance of fault classification algorithms more effectively than methods that rely solely on clustering or instance selection.

Methodology

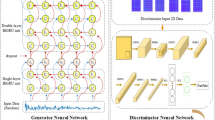

Generative adversarial network with auxiliary classifier

ACGAN originates from the Conditional Generative Adversarial Network (CGAN), which controls the class of generated samples by adding sample labeling information to the input of the generator. ACGAN is an extension of CGAN, in addition to adding label information in the input, ACGAN also uses a classifier to assist the discriminator. Therefore, ACGAN can not only determine whether a sample comes from the real distribution or the generated distribution, but also determine the category of the generated sample. In other words, a classification function is added to the discriminator of ACGAN, and its structure is shown in Fig. 4. In addition, it is proved that ACGAN can produce higher quality samples by adding more structures and/or specialized loss functions to the potential space of GAN.

Compared with the samples generated by the original GAN, each generated sample \(\:{i}_{\text{fake\:}}^{x}\) of ACGAN has a corresponding category label, which can be expressed as \(\:{i}_{\text{fake\:}}^{x}={A}_{\text{acgan\:}}\left({\text{\:label}}_{x},{k}_{x}\right)\). Where, \(\:{\text{\:label}}_{x}\) denotes the label corresponding to the ith sample; \(\:{k}_{x}\) denotes the x-th noise input. Due to the classification function of ACGAN, its loss function also consists of two parts, the discriminant loss \(\:{L}_{d}\) and the classification loss \(\:{L}_{c}\). \(\:{L}_{d}\) is the same as the discriminator loss function of GAN, as shown in Eq. (1).

Where:\(\:\:U\left(\text{}\text{predicted\:label}\text{\:=\:real\:|\:}{I}_{\text{real\:}}\right)\) denotes the probability that the input is a real sample and the predicted label given by the discriminator is also a real sample. \(\:U\left(\text{}\text{predicted\:label\:}=\text{\:generate}\text{d}\text{}\mid\:{I}_{fake}\right)\) denotes the probability that the input is a generated sample and the predicted label given by the discriminator is also a generated sample. The classification loss \(\:{L}_{c}\) is specific to ACGAN and is calculated as shown in Eq. (2).

Where: \(\:U\left(\text{\:categorical\:label\:=\:real\:label\:}\mid\:{I}_{\text{real\:}}\right)\),\(\:U\left(\text{\:categorical\:label\:=\:real\:label}\text{}\mid\:{I}_{\text{fake\:}}\right)\) represent the probability that “the inputs are real samples and generated samples, and the categorical labels given by the discriminator are consistent with the real category labels”.

In ACGAN, the discriminator maximizes \(\:{L}_{c}\)+\(\:{L}_{d}\) through model training. That is, it should be able to judge whether the sample belongs to the real sample or the generated sample, and it should be able to judge the category of the generated sample and the real sample. The generator maximizes \(\:{L}_{c}\)-\(\:{L}_{d}\) through model training. That is, in addition to generating samples that can “fool” the discriminator, the generator must also make the category of each generated sample close to its corresponding original category samples, so that the discriminator in the true and false discriminatory error, but in the identification of the sample category classification is correct.

Active generative oversampling method based on QBC and W_ACGAN

W_ACGAN model construction

To address the training instability issues of the original Auxiliary Classifier Generative Adversarial Network (ACGAN), this study introduces the Wasserstein distance from the Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network (WGAN) into the ACGAN framework, resulting in the W_ACGAN model. The Wasserstein distance is used to replace the Jensen-Shannon (JS) divergence, which helps mitigate the problem of gradient vanishing and improves the stability of the model during training.

In the original ACGAN, the discriminator is tasked with classifying real samples as positive examples and generated samples as negative examples. The loss function for the discriminator is expressed as follows:

Where:\(\:\:{U}_{r}\) denotes the distribution of real samples,\(\:\:{U}_{a}\) denotes the distribution of generated samples, and\(\:\:D\left(i\right)\) denotes the expression of the discriminator. When the parameters of the generator are fixed and the discriminator is trained, the contribution of any sample i (real sample or generated sample) to the loss function of the discriminator can be expressed as Eq. (4).

In order to obtain the optimal discriminator expression, the derivative of \(\:D\left(i\right)\) in Eq. (4) is made to be 0, which leads to Eq. (5).

Where: \(\:{U}_{r}\left(i\right)\) denotes the probability that the sample i comes from the true distribution; \(\:{U}_{a}\left(i\right)\) denotes the probability that the sample i comes from the generated distribution. The expression of the optimal discriminator \(\:D\left(i\right)\) can be obtained by simplifying Eq. (5), as shown in Eq. (6).

That is, when \(\:{U}_{r}\left(i\right)=0\) and \(\:{U}_{a}\left(i\right)\ne\:0\), the probability that the optimal discriminator gives the sample i from the true distribution is 0. When \(\:{U}_{r}\left(i\right)={U}_{a}\left(i\right)\), the probability that the sample i is from the true distribution and the generator distribution are equal. That is, the probability that the optimal discriminator gives the sample x from the true distribution is 0.5. Considering an extreme case, i.e., when the discriminator is trained to be optimal, the generator’s loss function is as follows. The loss function of the generator is

Where \(\:JS\left({U}_{r}\parallel\:{U}_{a}\right)\) is the JS dispersion between the true distribution \(\:{U}_{r}\) and the generated distribution \(\:{U}_{a}\), which can be calculated according to Eq. (8).

From this derivation, it is clear that when the discriminator is optimal, the generator’s loss function is transformed into minimizing the JS divergence between the real and generated sample distributions. However, when there is no significant overlap between the real distribution \(\:{U}_{r}\) and the generated distribution \(\:{U}_{a}\), the JS divergence remains constant at log2, leading to a gradient of zero for the generator’s loss function. This means the generator cannot be optimized, which is a major reason why GANs are difficult to train.

To address this issue, the Wasserstein distance is introduced to replace the JS divergence. The Wasserstein distance, also known as the Earth Mover’s Distance (EMD), measures the minimum amount of “work” required to transform one distribution into another. Unlike the JS divergence, which can become meaningless when the distributions do not overlap, the Wasserstein distance provides a meaningful measure of the distance between distributions even in such cases. This property makes the Wasserstein distance particularly suitable for GAN training, as it ensures that the generator receives useful gradient information regardless of the overlap between the real and generated distributions.

The Wasserstein distance \(\:M\left({U}_{r},{U}_{a}\right)\) can be calculated according to Eq. (9).

From Eq. (9), it can be seen that for the JS degree, the advantage of Wasserstein distance lies in the fact that regardless of whether there is an overlap between the true distribution \(\:{U}_{r}\) and the generated distribution \(\:{U}_{a}\). The Wasserstein distance can always reflect the distance between the two distributions. This indicates that the Wasserstein distance is relatively continuous and smooth, and can produce the gradient that the JS dispersion cannot provide. The introduction of Wasserstein distance can make the training of GAN more stable, and the loss function of the GAN generator becomes \(\:-{E}_{i\sim\:{U}_{a}}\left[D\right(i\left)\right]\), and the loss function of the discriminator becomes \(\:{E}_{i\sim\:{U}_{a}}\left[D\right(i\left)\right]-{E}_{i\sim\:{U}_{r}}\left[D\right(i\left)\right]\).

Compared to conventional ACGANs, which rely on the Jensen-Shannon (JS) divergence and often suffer from unstable training due to vanishing gradients and mode collapse, our W_ACGAN model leverages the Wasserstein distance to address these issues. The JS divergence struggles when the real and generated distributions do not overlap significantly, leading to unstable training and slow convergence. In contrast, the Wasserstein distance provides a smoother and more meaningful measure of the distance between distributions, even in cases of non-overlapping support. This ensures that the generator receives useful gradient information throughout the training process, resulting in more stable training and faster convergence. Additionally, the improved stability and convergence speed enable the generator to produce higher-quality and more diverse samples, which is particularly important for accurately representing minority classes in imbalanced datasets. By mitigating common GAN training issues, W_ACGAN achieves better performance in generating realistic and diverse samples, ultimately enhancing the overall classification performance.

W_ACGAN training guidance based on QBC and diversity

To enhance the diversity and quality of generated minority class samples, we integrate the QBC algorithm and a diversity metric into the training process of the W_ACGAN. The QBC algorithm selects samples with high entropy values from the generated pool, indicating high uncertainty and potential diversity. These samples are further evaluated using a diversity metric based on Euclidean distances to ensure they are not only informative but also uniformly distributed. The selected samples are then assigned labels corresponding to real samples and incorporated into the training of the discriminator, guiding the generator to produce more diverse and realistic outputs. This process is complemented by an adaptive training mechanism that dynamically adjusts the number of updates for the generator and discriminator based on their loss values, ensuring a balanced training process. This integration of QBC and diversity metrics significantly improves the performance of the collision risk prediction model by enhancing the representation of minority class samples.

Aiming at the problem of insufficient sample diversity in the original GAN, this paper introduces the QBC algorithm and Diversity evaluation index in the training process of W_ACGAN to guide W_ACGAN to generate diversified samples that are favorable to improve the collision classification effect. The QBC algorithm aims to select the sample with the most inconsistent classification results from the generated samples, that is, the sample that is more prone to recognition errors. Learning these samples is not only necessary, but also beneficial to the performance of the classifier. By embedding QBC into the training process of W_ACGAN, the diversity of generated samples is improved by selecting the samples that are more inconsistent with other samples from the samples selected by QBC. The specific process is as follows: firstly, the QBC algorithm is used to select M samples with high entropy value from the generated samples, and then \(\:\widehat{W}(\widehat{W}<W)\) samples are selected from them with the help of the diversity evaluation index. Secondly, the labels of these W samples are set as real sample labels, i.e., they are added to the original real sample set as real samples. Finally, the obtained real sample set is used to train the discriminator with the remaining generated samples.

When using the QBC algorithm to select samples, we first select Z training sets N1, N2 ,…,NZ from the training set that contains all samples in the form of bagging; and use the Z training sets to train Z independent classification models C1 ,C2 ,…,CZ, in order to form a set of committees \(\:C=\left\{{C}_{1},\right.\left.{C}_{2},\cdots\:,{C}_{Z}\right\}\). Second, the samples \(\:A\left({k}_{1}\right),A\left({k}_{2}\right),\cdots\:,A\left({k}_{y}\right),\cdots\:,A\left({k}_{r}\right)\)generated by the generator for r noise samples \(\:{k}_{1},{k}_{2}\cdots\:,{k}_{y},\cdots\:,{k}_{r}\) are fed into each of the Z classification models. Each sample will get Z predicted labels given by K classification models. Finally, the entropy values \(\:B\left[A\left({k}_{1}\right)\right],\cdots\:,B\left[A\left({k}_{y}\right)\right],\cdots\:,B\left[A\left({k}_{r}\right)\right]\) are computed for each of the r samples according to Eq. (10) and using the Z predicted labels.

Where:\(\:\:{U}_{y}^{\zeta\:}=u\left({\widehat{j}}_{y}=\zeta\:\mid\:A\left({k}_{y}\right)\right)\) denotes the probability that the y-th generated sample is predicted to be a minority class collision of class \(\:\zeta\:\) by the Z classification models. That is, \(\:\left({\widehat{j}}_{y}\right.\left.=\zeta\:\mid\:A\left({k}_{y}\right)\right)=\frac{{Z}_{\zeta\:}}{Z}\), \(\:{Z}_{\zeta\:}\) denotes the number of labels belonging to the \(\:\zeta\:\)-th class among the Z predicted labels of \(\:A\left({k}_{y}\right)\), and P is the number of collision categories of the minority class. When the predicted labels of the committee for the sample \(\:A\left({k}_{y}\right)\) are the same, from Eq. (10), its entropy value \(\:B\left[A\left({k}_{y}\right)\right]=0\). That is, for each classifier of the committee, the sample \(\:A\left({k}_{y}\right)\) belongs to the samples that can be easily and correctly categorized. Therefore, the inclusion of this sample contributes relatively little to improve the performance of the classifier. On the contrary, the larger the entropy value of a sample, the easier it is to be misclassified or the less recognizable it is, which means that the sample provides more information. Therefore, in this study, W samples with higher entropy values, i.e., \(\:\left\{{A}^{1},{A}^{2},\cdots\:,{A}^{z},\cdots\:,{A}^{W}\right\}\), are selected from r generated samples with \(\:{A}^{z}\in\:\left\{A\left({k}_{1}\right),\right.\left.A\left({k}_{2}\right),\cdots\:,A\left({k}_{y}\right),\cdots\:,A\left({k}_{r}\right)\right\}\), in order to improve the performance of the classifier. Where \(\:{A}^{z}\) is the z-th sample selected.

In order to ensure that the generated samples can be uniformly distributed and avoid the influence of a single bootstrap on the diversity of the generated samples, this paper designs a diversity evaluation index, and performs a secondary screening on the W samples \(\:\left\{{A}^{1},{A}^{2},\cdots\:,{A}^{z},\cdots\:,{A}^{W}\right\}\). The specific steps are as follows: firstly, a sample \(\:{A}^{z}\) is selected from \(\:\left\{{A}^{1},{A}^{2},\cdots\:,{A}^{z},\cdots\:,{A}^{W}\right\}\), and calculate the Euclidean distance \(\:E{d}_{z,1},E{d}_{z,2},\cdots\:,E{d}_{z,z-1}E{d}_{z,z+1},\cdots\:,E{d}_{z,W}\)between \(\:{A}^{z}\) and other W-1 samples in sequence according to Eq. (11).

Where \(\:E{d}_{z,p}\) denotes the Euclidean distance between \(\:{A}^{z}\) and the p-th sample \(\:{A}^{p}\). Secondly, all the obtained Euclidean distances, that is, \(\:E{d}_{z,1},E{d}_{z,2}\cdots\:,E{d}_{z,z-1},E{d}_{z,z+1},\cdots\:,E{d}_{z,W}\) are summed to obtain the Diversity value \(\:{D}_{z}\) for sample \(\:{A}^{z}\).

Similarly, Diversity values \(\:{D}_{1},{D}_{2},\cdots\:,{D}_{z-1},{D}_{z+1},\cdots\:,{D}_{W}\) are calculated for the remaining W-1 samples in turn. Finally, \(\:\widehat{W}\) samples \(\:{\widehat{A}}^{1},{\widehat{A}}^{2},\cdots\:,{\widehat{A}}^{{z}^{{\prime\:}}},\cdots\:,{\widehat{A}}^{W}\) with larger Diversity values are selected from \(\:\left\{{A}^{1},{A}^{2},\cdots\:,{A}^{z},\cdots\:,{A}^{W}\right\}\) as the final selection. Where,

. At the same time, the labels of these selected samples are set as true labels, i.e., True. The labels of the remaining unselected samples remain False. And the selected samples are treated as true samples to participate in the training of the discriminator in order to guide the generated samples to approximate in the direction of the selected samples.

In order to avoid that the difference between the selected samples and the original samples is too large, which leads to the samples generated by the generator to be in the direction of deviating from the real samples, this paper introduces an attenuation factor term \(\:\sigma\:(0<\sigma\:<1)\) into the loss of the selected samples to adjust the contribution of the selected samples in the discriminant loss function. The value of this attenuation factor will increase with the number of iterations. This is because at the beginning of training, the generated samples are different from the original samples, and the training should be guided by the real samples. As the number of iterations increases, the generated samples gradually approach the original samples. In this study, we hope that the generated samples are close to the direction of the selected samples. Therefore, the loss function of the final discriminator should contain two parts: ① the original loss, which contains two items: the loss of the real sample and the loss of the unselected sample. ② the loss of the selected samples with the added attenuation factor. As shown in Eq. (13).

Where: \(\:{i}_{l}\) denotes the lth real sample; L is the total number of real minority class samples; V is the total number of unselected generated samples.

Adaptive model parameter update based on loss value

In order to make the training of W_ACGAN more stable, this research controls the training from the discriminator and generator. When optimizing the generator, it is assumed that the discriminator’s discriminative ability is better than the current generator’s generative ability, so that the discriminator guides the generator to learn in a better direction. Specifically, the parameters of the discriminator are first updated one or more times, and then the parameters of the generator are updated. Different from the fixed mode of WGAN, that is, “update the discriminator 5 times, and then update the generator 1 time”, this paper proposes an adaptive training method. By calculating the ratio between the loss value of the last iteration and the loss value of the current iteration, we get the number of parameter updates of the discriminator and generator in the next iteration. Let the loss value of the last iteration discriminator be \(\:{d}_{\text{Loss\:}}^{\text{pre\:}}\), the loss value of the current iteration discriminator be \(\:{d}_{\text{Loss\:}}^{\text{curr\:}}\), the loss value of the last iteration generator be \(\:{a}_{\text{Loss\:}}^{\text{pre\:}}\),and the loss value of the current iteration generator be \(\:{a}_{\text{Loss\:}}^{\text{curr\:}}\). The steps of the adaptive training method proposed in this paper are as follows.

Step 1: Train the discriminator and the generator each once, and assign the loss values of the discriminator and the generator in the first iteration to \(\:{d}_{\text{Loss\:}}^{\text{pre\:}}\) and \(\:{a}_{\text{Loss\:}}^{\text{pre\:}}\), respectively. Then, train the discriminator and the generator each once, and assign the loss values of the discriminator and the generator in the second iteration to \(\:{d}_{\text{Loss\:}}^{\text{curr\:}}\) and \(\:{a}_{\text{Loss\:}}^{\text{curr\:}}\), respectively.

Step 2: Calculate the number of parameter updates \(\:{d}_{ns}\) for the discriminator in the next round of iterations using Eq. (14). To avoid an infinite number of updates due to the possibility that the loss value \(\:{d}_{\text{Loss\:}}^{\text{pre\:}}\) in the previous round of iterations may be 0, a very small floating-point number is added to the denominator.

Where \(\:{d}_{ns}^{w}\) and \(\:{d}_{ns}^{W}\) are the pre-set minimum and maximum number of updates of the discriminator parameters in each iteration for avoiding too many or too few updates. It can be seen that the training of the discriminator is a negative feedback process. That means the larger the loss of \(\:{d}_{\text{Loss\:}}^{\text{curr\:}}\) in this round of discriminator, the larger \(\:{d}_{ns}\) will be. As the loss of the discriminator decreases in the next iteration, the discriminator’s discriminative ability will be enhanced accordingly.

Step 3: Calculate the number of parameter updates \(\:{a}_{ns}\) of the generator in the next iteration by Eq. (15), similar to Eq. (14), with a floating point number ε added to the denominator.

Where \(\:{a}_{ns}^{w}\) and \(\:{a}_{ns}^{W}\) are the predefined minimum and maximum number of generator parameter updates per iteration, respectively. Contrary to the discriminator, the larger the generation loss \(\:{a}_{\text{Loss\:}}^{\text{curr\:}}\) is in this round, the smaller \(\:{a}_{ns}\) is, i.e., the generation loss of the generator will be larger. Therefore, the generator’s generating ability will not become stronger. The joint effect of Eq. (14) and Eq. (15) can ensure that the discriminator’s discriminative ability is always better than the generator’s generative ability, thus guiding the generator to generate higher quality samples.

Step 4: Assign the values of \(\:{d}_{\text{Loss\:}}^{\text{curr\:}}\) and \(\:{a}_{\text{Loss\:}}^{\text{curr\:}}\) to \(\:{d}_{\text{Loss\:}}^{\text{pre\:}}\)and \(\:{a}_{\text{Loss\:}}^{\text{pre\:}}\), respectively. Then, train the discriminator and the generator in accordance with the discriminator and generator parameter update counts, \(\:{d}_{ns}\), \(\:{a}_{ns}\), computed above, respectively.

Step 5: Calculate the loss values of the discriminator and generator, and assign them to \(\:{d}_{\text{Loss\:}}^{\text{curr\:}}\) and \(\:{a}_{\text{Loss\:}}^{\text{curr\:}}\), respectively.

Step 6: Repeat steps 3 to 5 until the number of iterations reaches a pre-set value Δ.

After training the active generative oversampling network model of this paper according to the above steps; input a set of noise samples to the generator with the same distribution of noise samples used for training; and inject the output of its corresponding generator into the original dataset by considering the output of its corresponding generator as a complementary sample of a few classes of samples to achieve the purpose of balancing the dataset.

The loss threshold sensitivity was determined by monitoring the loss values of both the discriminator and generator during the training process. Specifically, we observed the ratio between the loss values of consecutive iterations, as described in Eqs. (14) and (15). This ratio was used to dynamically adjust the number of updates for the discriminator and generator in each iteration. The key idea is to ensure that the discriminator’s discriminative ability remains stronger than the generator’s generative ability, thereby guiding the generator to produce higher-quality samples. The loss threshold was established through an empirical process, where we conducted multiple training runs on each dataset to identify the optimal range for the loss ratio. The minimum and maximum number of updates for the discriminator and generator, denoted as \(\:{d}_{ns}^{w}\), \(\:{d}_{ns}^{W}\), \(\:{a}_{ns}^{w}\)and \(\:{a}_{ns}^{W}\), were predefined based on these empirical observations. These values were chosen to prevent too few or too many updates, which could lead to underfitting or overfitting, respectively. To further refine the loss threshold, we introduced a small floating-point number ε in the denominator of Eqs. (14) and (15) to avoid division by zero and to ensure smooth gradient updates. This adjustment allowed us to maintain stable training across all datasets, regardless of their inherent imbalance or complexity.

Real-time collision prediction process based on the proposed method

Due to the poor quality as well as diversity of standard GAN generated samples, this paper proposes an active generative oversampling method for QBC and ACGAN. The distance between true and false sample distributions is measured by the smoother Wasserstein distance instead of the original JS scatter; and the ACGAN model, namely W_ACGAN, is constructed to improve the stability of its training. Secondly, QBC is used to select the most representative samples with good diversity from the samples generated by ACGAN, in order to guide ACGAN to generate more diverse minority samples. Meanwhile, an adaptive model training method based on loss value is proposed to improve the quality of generated samples by adjusting the training period of generator and discriminator to enhance the confrontation effect between generator and discriminator. Finally, a real-time collision classifier is constructed for risk prediction. The specific process is shown in Fig. 5.

Computational considerations and scalability

In our study, the computational requirements for implementing the proposed active generative oversampling method based on Query by Committee (QBC) and Wasserstein Auxiliary Classifier Generative Adversarial Network (W_ACGAN) are primarily driven by the training of the GAN framework and the iterative selection process involving QBC and diversity metrics. Specifically, the computational needs can be summarized as follows:

Training the W_ACGAN framework: The training process involves alternating updates between the generator and discriminator networks. Given the complexity of the Wasserstein distance calculation and the additional classification loss in ACGAN, the training requires a moderate amount of computational resources. For the experiments conducted in this study, we used a standard workstation equipped with an NVIDIA GPU, which allowed us to train the model within a reasonable timeframe (approximately [X] hours per dataset, depending on the dataset size).

QBC and diversity metric calculations: The QBC algorithm involves training multiple classification models and computing entropy values for sample selection. Additionally, the diversity metric calculation requires pairwise distance computations among selected samples. These steps, while computationally intensive, are manageable with modern hardware and can be optimized through parallel processing techniques.

Adaptive training mechanism: The adaptive parameter update mechanism based on loss values adds an additional layer of computational overhead, but it significantly improves the stability and quality of the generated samples. This adaptive approach ensures that the training process remains efficient and effective, even for large datasets.

Regarding scalability, especially for huge datasets, our method is designed with several considerations to address potential limitations: (1) Batch processing and Mini-Batch training: To handle large datasets efficiently, we employ mini-batch training for the GAN framework. This approach allows us to process data in manageable chunks, reducing memory requirements and enabling the use of larger datasets without overwhelming computational resources. (2) Parallelization and distributed computing: The training of multiple classification models in the QBC algorithm and the computation of diversity metrics can be parallelized across multiple processors or distributed computing environments. This parallelization significantly reduces the overall computation time and enhances the scalability of our approach. (3) Incremental learning and sample selection: By selectively enriching the minority class samples through QBC and diversity metrics, our method focuses on generating only the most informative samples. This incremental approach minimizes the computational burden associated with generating and processing large volumes of synthetic data. (4) Optimized network architecture: The generator and discriminator networks used in our W_ACGAN framework are designed to be lightweight yet effective. This balance ensures that the model remains computationally efficient while maintaining high performance.

While the proposed method is computationally intensive, its performance benefits in handling imbalanced datasets justify the additional resources required. By employing batch processing, parallelization, and an optimized network architecture, the scalability of the method can be significantly enhanced, making it more practical for large-scale applications.

The integration of the QBC and dynamic epoch adjustment mechanisms introduces additional computational overhead primarily due to the increased complexity of the model training process. Specifically, QBC requires the maintenance and evaluation of multiple models, which adds to the training time as each model undergoes several iterations. Additionally, the dynamic adjustment of epochs involves recalculating the optimal number of epochs during training, which can increase the computational burden as it adapts to the training dynamics.

While these mechanisms may lead to a rise in both training time and memory consumption compared to a baseline method without them, their implementation is aimed at improving model performance and adapting the training process more effectively to the specific dataset. The trade-off between computational cost and performance gain is a critical consideration when deploying this method in real-world applications, where the efficiency of the model must be balanced with available computational resources.

In our study, we did not conduct explicit benchmarks for training time and memory usage; however, the methods employed are designed to optimize training by refining the model’s learning process, which can justify the additional resource usage in cases where accuracy and performance improvements are prioritized.

Result analysis and discussion

As mentioned above, the main goal of this study is to use the proposed method to improve the performance of real-time collision prediction models trained on unbalanced datasets. A comprehensive comparison is made between the method of this paper and other classical sampling methods. The following are the datasets used for the study, the relevant settings for the experiments and some metrics used to evaluate the performance of the model.

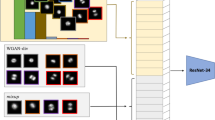

Data set selection

In the present investigation, four disparate and publicly accessible datasets pertaining to vehicular incidents were meticulously selected to scrutinize the influence of data imbalance on the prognostication of traffic collision risks within transportation systems.

-

(1)

The National Automotive Sampling System General Estimates System (NASS GES) Crash Database: This extensive dataset, curated by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), encompasses a comprehensive array of traffic collision instances. It serves as a quintessential data source for predictive analytics and subsequent analyses within the field of traffic safety.

-

(2)

The Kaggle State Farm Distracted Driver Detection (KSFDDD): While the primary intent of this dataset is the identification of distracted driving practices, it also encompasses a collection of traffic accident imagery. Notably, it exhibits pronounced imbalances across categories, rendering it an optimal subject for examining the challenges posed by data imbalance in traffic collision prediction models.

-

(3)

The Swiss Road Traffic Accident Database: This dataset chronicles vehicular accidents within Switzerland and is characterized by granular details such as temporal and locational data, vehicular types, and other pertinent descriptors. Despite its comparatively modest volume, the dataset is valued for its provision of authentic, real-world data for empirical study.

-

(4)

The UK Road Safety Dataset: Encompassing an extensive compendium of traffic collision information from the United Kingdom, this dataset includes variables indicative of accident severity, geographical coordinates, and vehicular classifications, among others.

Experimental setup

Based on the above four datasets, support vector machine (SVM), random forest (RF), multi-layer perceptron (MLP), convolutional neural networks (CNN), One Dimensional Convolutional Neural Net-work (CNN-1D), which are five kinds of classifiers. In the experiment, 70% of the dataset was randomly selected as the training set, and the remaining 30% as the test set. In order to minimize the bias of the randomly selected data on the test results, this paper conducted 100 trials on each classifier, and finally the average of the 100 trials was counted as the result of the test. The generators used in the test are Linear(z,256)-ReLU( )-Linear(256,256)-ReLU( )-Linear(256,Dim)-Sigmoid( ). The discriminator is Linear(Dim,256)-LeakyReLU(0.2)-Linear(256,256)-LeakyReLU(0.2)-Linear(256,1)-Sigmoid( ). The random vector dimension is 32, batch size is 32, learning rate is 0.0003, and the number of iterations is 1000. The internal parameters involved in the GAN network framework used in the experiments are consistent with the default ones.

Evaluation metrics

After fully understanding and comparing the advantages and disadvantages of various evaluation metrics, this paper chooses Precision, Recall, F-measure and G-mean as the evaluation metrics for this experiment.

Result analysis

Comparison of this paper’s method and six typical sampling methods, SMOTE, ADASYN, ENN, SPIDER2, CPM and GAN, with five classifiers on four unbalanced datasets. A comprehensive comparative analysis is carried out on the four evaluation indexes, and the experimental results are shown in Figs. 6, 7, 8 and 9. Where the horizontal coordinate indicates the data set, and the vertical coordinate indicates the value of the assessment indexes.

The present method gives better results than other sampling methods on all datasets on all 4 assessment indicators. The results of this method are above 0.92 on all 4 assessment indicators. In particular, it improves over the worst performing ENN by 23%, 24.5%, 28.3% and 16% on the average of the 5 datasets, respectively. It also improves over the next best performing GAN by 7.2%, 9%, 12% and 8.7%, respectively. This indicates that the proposed method outperforms other classical sampling methods in terms of better performance, better identification of collision samples and lower misclassification rate for non-collision samples. The reason for the best performance of this method is that it can fully consider the spatial distribution of the samples, and make the generated samples richer and more diversified through the repeated alternating optimization of the generative network and the discriminative network. SMOTE and ADASYN use k-nearest neighbors to create new samples, which are only distributed in some smaller regions. GAN takes into account the diversity of samples, so it performs the best among these comparative sampling methods. But its performance on each classifier is still slightly inferior to the present method. The main reason is that the W-ACGAN network of this method uses Wasserstein distance instead of the original JS dispersion to improve the training stability of the model and the quality of the generated samples. Meanwhile, the diversity evaluation index Diversity ensures the diversity of the selected samples.

In addition, in order to statistically evaluate the proposed method and compare it with the other six sampling methods, Win/Tie/Loss is used for evaluation. In all methods, the Wilcoxon signed rank test (p < 0.05) was performed for Precision, Recall, F-measure and G-mean. If the performance of this method was better than the other compared methods after statistical testing, the method was labeled as “Win”; otherwise, it was labeled as “Loss”. If there is no statistically significant difference between this method and the comparative methods, the case is labeled as “Tie”. Then, the number of times Win, Tie, and Loss were calculated for this method. By using Win/Tie/Loss evaluation, the advantages and disadvantages between this method and the comparison method can be clearly visualized. The comparison results are shown in Table 1.

To provide a more detailed understanding of how the proposed method balances sensitivity and specificity in collision and non-collision classifications, this paper conducts a comprehensive confusion matrix analysis. Confusion matrices are essential tools for evaluating the performance of classification models, as they clearly illustrate the number of true positives (TP), true negatives (TN), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN) for each class. This analysis is critical for assessing the effectiveness of the proposed method in handling imbalanced datasets.

For each dataset, we present the confusion matrices for our proposed method and compare them with those of the best-performing baseline methods (GAN, SMOTE, and ENN). The results are shown in Table 2, which summarize the TP, TN, FP, and FN values for each method using the Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier. We also calculate the sensitivity (recall) and specificity (precision) metrics from the confusion matrices to further quantify the performance improvements achieved by our method.

The proposed method consistently achieves a higher number of TP and TN across all datasets, while minimizing the number of FP and FN. This shows that our approach effectively balances sensitivity (recall rate) and specificity (precision) in collision and non-collision classification. The sensitivity of our method ranges from 0.89 to 0.92 and maintains a high specificity value (0.98 on all datasets). Compared with the benchmark methods (GAN, SMOTE and ENN), the proposed method has higher sensitivity and specificity, indicating its superior performance in processing unbalanced data sets. In particular, in the NASS GES crash database, the proposed method is 22.7%, 8.2% and 15% higher than ENN, GAN and SMOTE, respectively. In the KSFDDD database, the proposed method improved by 28.6%, 9.8%, and 20% compared to ENN, GAN, and SMOTE, respectively. In the Swiss Road Traffic Accident, the proposed method is 29.6%, 12.2% and 21.1% higher than ENN, GAN and SMOTE, respectively. In the UK Road Safety, the proposed method achieved a 29% improvement over ENN, a 9.9% improvement over GAN, and a 18.7% improvement over SMOTE.

To further illustrate the improvements achieved by the proposed method, this study presents examples of the most improved collision and non-collision samples in the dataset. Specifically, in the NASS GES collision database, the proposed method correctly identified 920 collision samples (TP), while ENN had 750, SMOTE had 800, and GAN had 850. Similarly, for non-collision samples, the proposed method achieved 8500 TN, while ENN achieved 8200 TN, SMOTE achieved 8300 TN, and GAN achieved 8400 TN. The experimental results show that this method can enhance collision and non-collision classification in imbalanced datasets.

Conclusion

This study introduces an advanced active generative oversampling strategy that integrates Query by Committee (QBC) and Auxiliary Classifier Generative Adversarial Network (ACGAN) within the Wasserstein GAN (WGAN) framework to address data imbalance in collision risk prediction. Our method significantly enhances the diversity and quality of generated minority class samples, leading to improved classification performance. Key findings include: (1) Enhanced sample diversity: By combining QBC and W_ACGAN, our method generates more diverse and high-quality minority class samples, crucial for improving model performance in imbalanced datasets. (2) Improved stability and performance: The use of Wasserstein distance mitigates common GAN training issues, such as instability and lack of sample diversity, resulting in higher quality synthetic samples. (3) Superior classification results: Empirical evaluations on four publicly available datasets demonstrate that our method outperforms existing techniques in terms of precision, recall, F-measure, and G-mean, with an average improvement of 23–28.3% compared to the worst-performing method.

This research has achieved promising results with the proposed generative oversampling method, there are limitations that warrant attention for future work. The generalizability of the proposed method across different datasets and its computational complexity, particularly with large datasets, are areas that require further investigation. In addition, we will have access to more advanced computational resources in future studies to thoroughly analyze and visualize the generated samples.

To further enhance the applicability and impact of the proposed method, we outline several potential directions for future research: (1) Integration with Reinforcement Learning (RL): The proposed method could be integrated with RL to dynamically adjust the oversampling process and optimize training parameters, leading to more adaptive and efficient models. This would allow the model to adaptively focus on the most challenging or underrepresented samples, further enhancing the diversity and quality of the generated data. (2) Application to fraud detection: The proposed method could be applied to fraud detection. The real-time nature of the proposed method makes it particularly suitable for fraud detection systems, where timely identification of fraudulent activities is crucial. The adaptive training mechanism could be further refined to handle streaming data, allowing the model to continuously learn and adapt to new types of fraud as they emerge. (3) Application to medical diagnostics: Medical diagnostics often involve imbalanced datasets, where certain diseases or conditions are rare compared to others. The proposed method could be applied to generate synthetic samples for rare diseases, improving the performance of diagnostic models. For example, in cancer detection, the model could generate synthetic samples for rare types of cancer, enabling more accurate and early diagnosis.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Xiangmin, G. et al. A survey of safety separation management and collision avoidance approaches of civil UAS operating in integration National airspace system. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 33 (11), 2851–2863 (2020).

Ahmad, S. et al. Accident risk prediction and avoidance in intelligent semi-autonomous vehicles based on road safety data and driver biological behaviours. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 38 (4), 4591–4601 (2020).

Fu, Y. et al. A survey of driving safety with sensing, vehicular communications, and artificial intelligence-based collision avoidance. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23 (7), 6142–6163 (2021).

Ma, X., Yu, Q. & Liu, J. Modeling urban freeway Rear-End collision risk using machine learning algorithms. Sustainability 14 (19), 12047 (2022).

Uriot, T. et al. Spacecraft collision avoidance challenge: design and results of a machine learning competition. Astrodynamics 6 (2), 121–140 (2022).

Li, W. et al. Risk analysis of pulmonary metastasis of chondrosarcoma by Establishing and validating a new clinical prediction model: a clinical study based on SEER database. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 22 (1), 529 (2021).

Zhou, X. et al. Distribution bias aware collaborative generative adversarial network for imbalanced deep learning in industrial IoT. IEEE Trans. Industr. Inf. 19 (1), 570–580 (2022).

Gao, Y., Zhai, P. & Mosalam, K. M. Balanced semisupervised generative adversarial network for damage assessment from low-data imbalanced‐class regime. Computer-Aided Civil Infrastructure Eng. 36 (9), 1094–1113 (2021).

Li, J. & Dai, C. Fast prototype selection algorithm based on adjacent neighbourhood and boundary approximation. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 20108 (2022).

Swana, E. F., Doorsamy, W. & Bokoro, P. Tomek link and SMOTE approaches for machine fault classification with an imbalanced dataset. Sensors 22 (9), 3246 (2022).

Balla, A. et al. The effect of dataset imbalance on the performance of SCADA intrusion detection systems. Sensors 23 (2), 758 (2023).

Yang, F. et al. A hybrid sampling algorithm combining synthetic minority over-sampling technique and edited nearest neighbor for missed abortion diagnosis. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 22 (1), 344 (2022).

Guzmán-Ponce, A. et al. A new under-sampling method to face class overlap and imbalance. Appl. Sci. 10 (15), 5164 (2020).

Upadhyay, K. et al. State of the Art on data level methods to address class imbalance problem in binary classification. GIS Sci. J. 8 (3), 875–903 (2021).

Pratap, V. & Singh, A. P. Novel fuzzy clustering-based undersampling framework for class imbalance problem. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manage. 14 (3), 967–976 (2023).

Kaur, P. & Gosain, A. Robust hybrid data-level sampling approach to handle imbalanced data during classification. Soft. Comput. 24 (20), 15715–15732 (2020).

Cao, L. & Shen, H. CSS: handling imbalanced data by improved clustering with stratified sampling. Concurrency Computation: Pract. Experience, 34(2), e6071. (2022).

Kobat, S. G. et al. Automated diabetic retinopathy detection using horizontal and vertical patch division-based pre-trained DenseNET with digital fundus images. Diagnostics, 12(8), 1975. (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Exploratory study on classification of diabetes mellitus through a combined random forest classifier. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 21 (1), 1–14 (2021).

Gao, S. et al. Seismic predictions of fluids via supervised deep learning: incorporating various class-rebalance strategies. Geophysics 88 (4), M185–M200 (2023).

Liu, Z. T. et al. Speech emotion recognition based on selective interpolation synthetic minority over-sampling technique in small sample environment. Sensors 20 (8), 2297 (2020).

Ning, Q., Zhao, X. & Ma, Z. A novel method for identification of glutarylation sites combining Borderline-SMOTE with Tomek links technique in imbalanced data. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinf. 19 (5), 2632–2641 (2021).

Meidianingsih, Q. & Agustine, D. Study of bagging application in the Safe-Level Smote method in handling unbalanced classification: Kajian Penerapan bagging Pada metode Safe-Level Smote Dalam Penanganan Klasifikasi Kelas Tidak Seimbang. Indonesian J. Stat. Its Appl. 5 (1), 105–116 (2021).

Halim, A. M., Dwifebri, M. & Nhita, F. Handling imbalanced data sets using SMOTE and ADASYN to improve classification performance of Ecoli data sets. Building Inf. Technol. Sci. (BITS). 5 (1), 246–253 (2023).

Wei, Y. et al. An improved unsupervised representation learning generative adversarial network for remote sensing image scene classification. Remote Sens. Lett. 11 (6), 598–607 (2020).

Ahsan, R. et al. A comparative analysis of CGAN-based oversampling for anomaly detection. IET Cyber-Physical Systems: Theory Appl. 7 (1), 40–50 (2022).

Tang, Z. R. et al. Few-sample generation of amount in figures for financial multi-bill scene based on GAN. IEEE Trans. Comput. Social Syst. 10 (3), 1326–1334 (2021).

Rangel-Díaz-de-la-Vega, A. et al. Impact of imbalanced datasets preprocessing in the performance of associative classifiers. Appl. Sci. 10 (8), 2779 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. An adaptive fault diagnosis method of power Transformers based on combining oversampling and cost-sensitive learning. IET Smart Grid. 4 (6), 623–635 (2021).

Huang, M. W. et al. On combining feature selection and over-sampling techniques for breast cancer prediction. Appl. Sci. 11 (14), 6574 (2021).

Karthikeyan, S. & Kathirvalavakumar, T. A hybrid data resampling algorithm combining leader and SMOTE for classifying the high imbalanced datasets. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 16 (16), 1214–1220 (2023).

Devi Priya, R. et al. Multi-Objective particle swarm optimization based preprocessing of Multi-Class extremely imbalanced datasets. Int. J. Uncertain. Fuzziness Knowledge-Based Syst. 30 (05), 735–755 (2022).

Merdas, H. M. Elastic Net–MLP–SMOTE (EMS)-Based model for enhancing stroke prediction. Medinformatics 1 (2), 73–78 (2024).

Deng, S., Zhu, Y., Liu, R. & Xu, W. Financial futures prediction using fuzzy rough set and synthetic minority oversampling technique. Adv. Math. Phys. 2022(1), 7622906 (2022).

Funding

The research in this article was not funded by any funds or projects, and was jointly completed by the author and co-authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Li Li contribution lies in data analysis, original draft preparation and sorting, Xiaoliang Zhang participated in the relevant revisions of the section " Experiment and Analysis “. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, L., Zhang, X. Addressing data imbalance in collision risk prediction with active generative oversampling. Sci Rep 15, 9133 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93851-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93851-3