Abstract

This study evaluated the association between long-term exercise with different osteogenic index, dietary patterns, body composition, biological factors, and bone mineral density (BMD) in 199 female elite masters athletes endurance athletes (EA), speed-power athletes (SPA), and throwing athletes (TA). Bone parameters in the distal (dis) and proximal (prox) parts of the forearm were measured by densitometry. Body compositions were analyzed using bioelectrical impedance analysis. Biological factors and lifetime bone fracture status were rated via face-to-face interviews. Dietary patterns and usual dietary intake were assessed using a semiquantitative NHANES Food Frequency Questionnaire. In female elite masters athletes the main parameters affecting BMD dis were age at menopause (small effect: η² = 0.03), number of fractures (small effect: η² = 0.05), number of dairy products per day (small effect: η² = 0.05), type of dietary pattern (small effect: η² = 0.04) and sport competition, type by OI (small effect: η² = 0.03). BMD prox was affected by age at menarche (medium effect: η² = 0.096), age at menopause (large effect: η² = 0.12), past fractures (small effect: η² = 0.02), dairy product (large effect: η² = 0.13), type of dietary pattern (small effect: η² = 0.04) and sports competition (medium effect: η² = 0.06). In both groups of women, EA and SPA dietary pattern with high intake of fruit, vegetables, dairy products, whole grains, poultry, fish, nuts, and legumes had a greater mean BMD. In contrast, in the TA group dietary pattern with lactose-free, and gluten-free determined higher mean BMD. Late menarche determined higher mean BMD in all groups of women, especially in TA. Physical activity helps maintain bone mineralization during aging. The long-term effects of athletic training, especially exercises such as throwing, have been confirmed in these studies. It is therefore worth considering popularizing these exercises for healthy aging.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aging as a concept has been vastly explored. An essential aspect is defining what it means to age well and to be healthy. In the case of bone tissue, healthy aging means maintaining good mineralization and bone mass for as long as possible, preventing the development of osteoporosis and bone fractures. The most important factors related to bone mineralization and bone mass acquisition are endocrine and mechanical factors, such as habitual physical activity1,2,3, low sedentary time4,5,6, a healthy diet7,8, and sun exposure3,9. Bone mineralization is also determined by genetic conditions10, ethnicity11, the occurrence of other diseases affecting the development of osteoporosis12, age, somatic and body composition, and the sex of the individual13.

A physical activity lifestyle is highly beneficial for increasing bone mineral density (BMD) and bone mineral content (BMC) to limit the emergence of osteopenia and osteoporosis development2,14. However, there is insufficient evidence regarding the extent of intensity and length of exercise required for osteogenic bone stimulation to occur at various skeletal locations. The osteogenic effect on bone tissue is important. Different forms of physical activity and types of sports have different osteogenic index (OI). Previous studies have shown that the accrual of bone mass can be optimized by mechanical loading through exercise interventions with large OI such as running, jumping, and weight-bearing activities15,16,17,18. It has not been proven, until recently, what training component has the strongest effect on human bone structure: type of stress, intensity, frequency, or duration19,20.

In addition to physical activity a strong determinant of bone tissue is the type of diet and eating habits. Traditionally, nutrition research has focused on single nutrients concerning bone health. However, this approach is limited. It does not account for dietary quality or nutrient synergy. The effect of a single nutrient on bone may be too small to detect21,22. New trends in studies of the effects of diet on health, including bone health, are increasingly based on analyses of dietary patterns. It is important to understand the influence of nutrients not only in isolation but also in the context of a dietary pattern, which is a complex mixture of nutrients7. The results from the Framingham Study Cohorts have shown dietary patterns to be predictive of BMD among adults22,23. Some studies have shown that a diet with a high intake of fruit, vegetables, low-fat dairy products, whole grains, poultry, fish, nuts, and legumes has a positive effect on bone status. This dietary pattern can be associated with a greater BMD and a lower risk of osteoporosis and fracture24. Some studies have shown that adherence to a Mediterranean diet protects against osteoporosis and has a positive effect on vitamin D levels25,26,27. In contrast, the Western diet is characterized by a high number of processed foods and is strongly correlated with lower BMD compared to other study groups22. An extensive meta-analysis was conducted in 2009 by Ho-Pham comparing BMD vegetarians to BMD controls. Revealed that vegetarians had nearly 4% lower BMD at both the femoral neck and lumbar spine than did individuals in the normal diet control group28. Despite various hypotheses regarding the correlation between a ketogenic diet and bone health, it is unclear whether a ketogenic diet has any effect on bone health in adults29. Intervention studies have shown the beneficial effects of dairy products on bone capital accumulation during growth and on bone turnover in adults. Observational studies have shown that consumption of dairy products, especially fermented dairy products that provide probiotics in addition to calcium, phosphorus, and protein, is associated with a lower risk of femoral neck fracture30.

In addition to the influence of lifestyle factors such as physical activity and nutrition, women’s biological, hormonal status has also been shown to be related to BMD levels. Age at menarche directly affects female estrogen levels, which play a vital role in bone tissue metabolism. The exact relationship between age at menarche and bone mineral status is not fully understood and described31. Some studies have shown that early menarche was positively associated with high BMD. Late menarche was associated with decreased BMD and increased risk of osteoporosis32. Other studies suggested no correlation between age at menarche and bone mineral status33. Some of the studies showed that early menarche is associated with an increased risk of adverse health outcomes, such as cardiovascular diseases, and cancers34,35. Other studies have shown that late menarche age may have a higher risk of lumbar osteoporotic fractures31. Most studies focused on mean age at menarche, with the frequency of early or late menarche rarely evaluated. It is known from research that after menopause, the rate of bone mass loss increases. The dynamics of these changes depend on whether women have risk factors for osteoporosis. Then the process of bone destruction will exceed the process of bone formation. The influence of biological variables on BMD has been a common topic of research in the general population. Much less frequently, such analyses were conducted among women training in the Masters category.

It is also worth mentioning a number of other potential factors that may affect bone mineral status in women, such as economic status, fertility, and diseases that disrupt bone metabolism. However, explaining the mechanisms of the influence of these variables on BMD requires further extended studies.

Given that BMD in women is influenced by a number of variables. In addition, the strength and direction of the relationship between these characteristics and BMD has not yet been indicated in previous studies. Also, there is a lack of evidence on the intensity of exercise, the type of training and its effect on bone health in women which substantiates our study. In this project, we planned multivariate analyses. This study evaluated the association between long-term exercise with different osteogenic index, dietary patterns, body composition, biological factors, and forearm BMD in 199 female elite masters athletes endurance athletes (EA), speed-power athletes (SPA), and throwing athletes (TA).

Methods

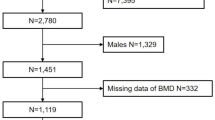

Participants and procedures

The study included 199 women aged 57.6 ± 11.2 years, athletes in the Masters category, and participants at the World Masters Athletics Indoor Championships (Poland, Torun 2023) and European Masters Athletics Championships Indoor (Poland, Torun 2024). The research was conducted as part of the International Track and Field Masters Athletes Cohort Study Project. All women studied were of the same ethnic origin (Caucasian, European Origin). All were regular participants of international athletic championships who had trained in athletics since their youth and reported a current training frequency of at least four times a week. The athletes were divided into 3 categories according to the declared type of event during the competition: endurance athletes (EA: medium and long-distance running: 800 m, 1500 m, steeplechase running, marathon, cross country), speed-power athletes (SPA: sprint 60 m, 200 m, 400 m, high jump, long jump, hurdles, pentathlon, triple jump), and throwing athletes (TA: hammer throw, discus, shot put, javelin throw, weight throw). Criteria for exclusion from the study included factors affecting the development of secondary osteoporosis. Secondary causes of bone loss can involve any underlying process and medical problem, as well as the use of certain medications, which can either affect achieving peak bone mass as a young adult or result in excessive bone resorption, affecting bone health and quality. The exclusion criteria included bone metabolic diseases, kidney disease, thyroid and parathyroid diseases, cancers, rheumatoid arthritis, and long-term steroid treatment.

This study carried out all methods according to relevant guidelines and regulations. The project complies with the principles of bioethics, as confirmed by the Bioethics Committee of the National Institute of Public Health, National Institute of Hygiene in Warsaw (protocol number 1/2021). The Bioethics Committee approved the research. All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The work was carried out according to the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki for experiments involving humans. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Bone tissue parameters and anthropometric measurements

Bone parameters (BMC, BMD, T-score) of the nondominant forearm were measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (Model: Stratec, Swissray-USA, Norland Medical Systems Madison WI, USA). The measurements were taken at two regions of interest (ROIs): the distal and proximal (spans 10 mm starting at the 1/3 forearm length and continuing proximally) parts of the forearm and the results are given for the radiale plus ulna (R + U). The measurement scan speed for high precision was 2 mm/sec. The densitometer was calibrated every morning using the original phantoms recommended by the manufacturer. Bone examination was performed once. The effective dose (µSv) for this densitometer was 0.05. The T-score is a comparison of a patient’s BMD to that of a healthy thirty-year-old individual of the same sex and ethnicity expressed in standard deviations. Bone parameters were measured according to the adopted densitometry methodology and the recommendations of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry36. The examination was performed by a team with the certificates needed to perform peripheral and axial densitometry and who was experienced in densitometry.

The anthropometric measurement protocol described by Hall et al.37 was used. All measurements were performed according to the applicable methodology and with the same measurement instruments. The nondominant forearm length was measured using large callipers (GPM Large Spreading Caliper) at the radiale-stylion points (r - sty) with an accuracy of 1 mm. Body height (basis - vertex) was measured two times with an anthropometer (GPM, Siber Hegner, Zurich, Switzerland) with an accuracy of 1 mm by a qualified anthropologist. Body mass (in kg), fat mass (FM in kg), percentage of body fat (PBF), and fat-free mass (FFM in kg) were analyzed using the JAWON Medical x-scan device based on bioelectrical impedance analysis. The examination was performed by a physical anthropology team.

Biological factors and bone fractures over a lifetime

Biological factors such as age at menarche, age at menopause, menopausal status, and lifetime bone fracture status were rated via face-to-face interviews. The interview data were collected by a specialist of biological age. Menarche occurs between the ages of 10 and 16 years in contemporary girls from developed countries. This study used the age at menarche categories recommended for the Caucasian European Origin population. Age at menarche below 10 years is classified as early. The age of menarche is above 15 years as late38,39. We used the hormonal status classification recommended by the World Health Organization. Premenopause is the period before menopause characterized by rhythmic menstrual cycles). Perimenopause is the period immediately preceding menopause, in which menstrual cycles are longer and irregular). Postmenopause is natural menopause. Information on the occurrence of osteoporosis in the family was collected in a direct interview40.

Dietary pattern

Usual dietary intake was assessed at the face-to-face interview using a semiquantitative NHANES Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ). The habitual dietary intake was assessed using a semiquantitative NHANES Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ). Nutritional data were collected during the face-to-face interview with every participant woman by a qualified and experienced sports dietitian. The components of an FFQ are a food list and a response section eliciting how often each item was eaten in a given time interval and quantity of consumption. “The photo album of products and foods” was used, as recommended, as a tool in research on assessing actual consumption, especially on a population scale. After the interview was completed, the respondent’s gifted answers were verified again. Quantitative data on dairy product consumption (number per day) so milk and any of the foods made from milk, including butter, cheese, ice cream, yogurt, condensed and dried milk, dietary supplementation, calcium supplementation, and vitamin D supplementation were also collected. Based on previous studies of the effect of dietary patterns on bone status, this study also assessed the frequency and effect of key dietary patterns on BMD41. Cluster analysis classified participants into dietary patterns using food subgroup servings. Clustering as a data analysis technique allowed observations (in this case, foods) to be grouped into groups or clusters in such a way that the characteristics (or variables; in this case, nutrients in food relevant to bone health such as calcium, protein, vitamin D, phosphorus, magnesium) of observations in a given cluster are more similar to each other than to observations (foods) in other clusters. Factor analysis revealed the following four dietary patterns: no.1- traditional diet/normal diet; no.2 - lactose-free, gluten-free; no.3 - with a high intake of fruit, vegetables, dairy products, whole grains, poultry, fish, nuts, and legumes; no.4 - vegan, vegetarian.

Statistical analysis

All calculations were performed with STATISTICA software (v. 12.0, StatSoft, USA). The normality of the distribution was verified by the Shapiro-Wilk test. The assumption of equality of variances was assessed with the Levene test of homogeneity of variance. The data analysis was based on factor analysis of variance ANOVA and the Bonferroni post hoc test. The effect size was calculated as eta-squared (η2) (small effect < 0.06; medium effect 0.06–0.14; large effect > 0.14)42. Differences between the frequency of low BMD in two ROIs: the distal and proximal parts of the forearm, and between the categories of biological age, dietary pattern, and diet supplementation were analyzed with the chi-square test. It also evaluated the effect size for chi-square which indicates the strength or magnitude of an observed effect. In this analysis, the following Phi coefficients (Φ - phi factor), ranging from no association (0) to perfect (1) were used. To determine the relationships between BMD, and BMC in two ROIs: the distal and proximal parts of the forearm, and exercise with different osteogenic index (OI), dietary patterns, body compositions, and biological factors in female elite Masters Athletes, ANCOVA was applied. The degree of correlation of the predictors was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF) collinearity test, taking a not-to-exceed value of 10. Residual analysis was also performed, testing for homoscedasticity using the White test and the degree of correlation of the residuals using the Durbin-Watson test. The effect size was calculated as eta-squared (η2) (small effect: <0.06; medium effect: 0.06–0.14; large effect: >0.14). Relationships of sport competition category and type of dietary pattern (no.1- traditional diet/normal diet; no.2 - lactose-free, gluten-free; no.3 - with a high intake of fruit, vegetables, dairy products, whole grains, poultry, fish, nuts, and legumes; no.4 - vegan, vegetarian) with BMD (mean dis and prox) were evaluated using two-way ANOVA. The statistical significance was set at α < 0.01; α < 0.001 for all analyses.

Results

Comparison of somatic, bone, and biological characteristics between EA, SPA and TA

The analysis of individual variables in female masters athletics is presented in Table 1. The groups differed significantly in 12 of 17 analyzed indicators, especially bone indicators and body composition. The TA group had significantly greater body mass (large effect; η2 = 0.50), body height (medium effect; η2 = 0.10), BMI (large effect; η2 = 0.42), FM (large effect; η2 = 0.51), PBF (large effect; η2 = 0.34) and FFM (large effect; η2 = 0.31) than did the EA and SPA groups. Additionally, the SPA group had significantly greater body height (medium effect; η2 = 0.10) and FFM (large effect; η2 = 0.31) than did the EA group. Almost all values of bone indicators were highest in TA with large OI. Compared with EA and SPA, TA significantly increased the BMD dis (medium effect; η2 = 0.42), BMC dis (medium effect; η2 = 0.06), T-score dis (small effect; η2 = 0.03), BMD prox (small effect; η2 = 0.04), BMC prox (medium effect; η2 = 0.12) and T-score prox (medium effect; η2 = 0.09), (Table 1).

Frequency of low BMD, the categories of biological age, dietary pattern, and diet supplementation in EA, SPA and TA

Table 2 presents the frequency of low BMD in two ROIs: namely, the distal and proximal parts of the forearm, and the categories of biological age, dietary pattern, and diet supplementation in female masters athletes in 3 categories of sport competition: endurance athletes (EA), speed-power athletes (SPA) and throwing athletes (TA). The desired value (T-score – 1.0 or above) of proximal forearm BMD occurred significantly more often in the TA group than in the EA (by 22.3%) and SPA groups (by 30.4%), (Table 2).

Relationships between BMD, BMC and exercise with different OI, dietary patterns, body compositions, and biological factors

Table 3 presents the relationships between bone parameters and exercise with different OI, dietary patterns, body compositions, and biological factors. The results of the covariance analyses between bone parameters and selected parameters indicated that in the case of elite masters athletes women, the main parameters affecting BMD dis were age at menopause (small effect: η² = 0.03), number of fractures (small effect: η² = 0.05), number of dairy products per day (small effect: η² = 0.05), type of dietary pattern (small effect: η² = 0.04) and sport competition, type by OI (small effect: η² = 0.03). BMD prox was affected by age at menarche (medium effect: η² = 0.096), age at menopause (large effect: η² = 0.12), past fractures (small effect: η² = 0.02), dairy product (large effect: η² = 0.13), type of dietary pattern (small effect: η² = 0.04) and sports competition (medium effect: η² = 0.06). Similar analyses were conducted for dis and prox BMC. The results of the covariance analyses between BMC dis and selected parameters indicated that in the case of masters athletes women, the main parameters affecting BMC dis were age at menarche (small effect: η² = 0.04), age at menopause (small effect: η² = 0.05), past fractures (small effect: η² = 0.05), dairy product (medium effect: η² = 0.06), type of dietary pattern (small effect: η² = 0.04) and sport competition (medium effect: η² = 0.03). The BMC prox was affected by age at menarche (medium effect: η² = 0.09), age at menopause (small effect: η² = 0.04), FM (small effect: η² = 0.02), dairy product (medium effect: η² = 0.07), type of dietary pattern (small effect: η² = 0.04) and sports competition (medium effect: η² = 0.07). Factors such as age at menopause and menarche, along with dietary intake, significantly affected BMD and BMC, highlighting the importance of nutrition, particularly dairy consumption, for bone health (Table 3).

Relationships of sport competition category and type of dietary pattern with BMD and BMC

Figure 1 presents the relationships of sport competition category and type of dietary pattern with BMD (mean dis and prox), (two-way ANOVA results) of the women studied. There were clearly significant interactions between the variables studied. In both groups of women EA and SPA dietary pattern no. 3 (high intake of fruit, vegetables, dairy products, whole grains, poultry, fish, nuts, and legumes) had a greater mean BMD. In contrast, in the TA group dietary pattern no. 2 (lactose-free, gluten-free) determined higher mean BMD (Fig. 1).

Relationships of sport competition category and type of dietary pattern with BMD (mean dis and prox), Dietary pattern: no.1- traditional diet/normal diet; no.2- lactose-free, gluten-free; no. 3- high intake of fruit, vegetables, dairy products, whole grains, poultry, fish, nuts and legumes; no.4.- vegan, vegetarian; (results two-way ANOVA; F = 4.509; p = 0.0003; η2 = 0.13; vertical lines − 0.95 CI - confidence intervals)

Figure 2 presents the relationships between sport competition category and the type of dietary pattern and the BMC (mean dis and prox), (two-way ANOVA results) of the masters athletes women studied. Similar results for BMD were reported. In both groups of women EA and SPA dietary pattern no. 3 (high intake of fruit, vegetables, dairy products, whole grains, poultry, fish, nuts, and legumes) had a greater mean BMC. In contrast, in the TA group dietary pattern no. 2 (lactose-free, gluten-free) had a greater mean BMC (Fig. 2).

Relationships of sport competition category and type of dietary pattern with BMC (mean dis and prox), Dietary pattern: no.1- traditional diet/normal diet; no.2- lactose-free, gluten-free; no. 3- high intake of fruit, vegetables, dairy products, whole grains, poultry, fish, nuts and legumes; no.4.- vegan, vegetarian; (results two-way ANOVA; F = 2.590; p = 0.0196; η2 = 0.08; vertical lines − 0.95 CI - confidence intervals)

Relationships of sport competition category and age at menarche category with BMD and BMC

Figure 3 presents the relationships between the sports competition category and age at menarche category and BMD (mean dis and prox), (two-way ANOVA results) of the women studied. There were clear significant interactions between the variables studied. In all groups of women TA, EA, and SPA late menarche determined higher mean BMD (Fig. 3).

Figure 4 presents the relationships of sport competition category and age at menarche category and BMC (mean dis and prox), (two-way ANOVA results) of the women studied. There were clear significant interactions between the variables studied. In all groups of women TA, EA and SPA late menarche determined higher mean BMD, especially in TA (Fig. 4).

Discussion

This study used forearm bone parameters data from different types of track and field female athletes aged 40 years and over from the European and World Masters Athletics Indoor Championships. The results suggest that bone mineral density (BMD) in the forearm of female masters athletes is strongly affected by biological factors such as age at menopause, age at menarche, number of fractures, number of dairy products per day, type of dietary pattern, and especially sports competition. In the case of masters athletes women, the main parameters affecting BMC were age at menarche, age at menopause, past fractures, dairy products, type of dietary pattern, and sports competition.

Multifactorial determinants of bone mineralization have been the subject of numerous studies in the general population43,44,45. There is much less research focused on specific groups such as female athletics trainees over the age of 4046,47,48.

Long-term exercise training and bone mineralization

In this study females in the TA group had significantly greater BMD dis, BMC dis, T-score dis, BMD prox, BMC prox, and T-score prox than those in the EA and SPA. Master athletes offer a model to examine associations between long-term exercise training and bone mineralization. The bone adapts to the mechanical loading it experiences during physical activity. In many studies, positive associations between PA levels and bone strength in older adults have been reported49,50. This study suggested that exercise is an effective way to improve and maintain BMD. There is also uncertainty over the types of activities that are potentially osteogenic. The effects of different muscle-loading exercise modes and volumes on musculoskeletal health are not well-studied in older populations51.

To fully understand the effect of activity on bone mineralization, it is necessary to take into account not only the duration of activity but also the type of activity, and the type of exercise according to the osteogenic effect. In our study, the type of athletic competition was important. Athletic throws are characterized by a large proportion of weight-bearing exercises during training, and they cause considerable pressure on the bone improving its strength. This type of training has a high osteogenic index. Moreover, in the case of the masters category, such physical activity has a long-term impact. Similar results were shown in earlier studies3. The results of two distinct cohorts of masters athletes with 10 years of training experience, Olympic weightlifters and distance runners, showed that greater total and regional BMD in Olympic weightlifters than in runners may reduce the risk of developing osteoporosis52. Piasecki et al.46 in a masters study (38 master sprint runners males and females, mean age 71 ± 7 years, and 149 master endurance runners males and females, mean age 70 ± 6 years) showed that regular running is associated with greater BMD at fracture-prone hip and spine sites in master sprinters but not in runners. In our study, female masters with SPA also had better bone mineralization than the EA group.

The available research highlights the most appropriate features of exercise for increasing bone density: weight-bearing aerobic exercises, i.e., walking, stair climbing, jogging, and Tai Chi, multicomponent exercises consist of a combination of different methods (aerobics, strengthening, progressive resistance, balancing, and dancing) aimed at increasing or preserving bone mass. However, for these protocols to be effective they must always contain a proportion of strengthening and resistance exercises53.

Interactions of sport competition category and type of dietary pattern with BMD and BMC

The positive and beneficial effects of physical activity and sports training on bone mineralization may be supported or reduced by other factors. In our study, we analyzed dietary patterns more accurately than individual dietary data. This study had significant interactions of sport competition category and type of dietary pattern with BMD and BMC. In both groups of women, EA and SPA, dietary pattern with a high intake of fruit, vegetables, dairy products, whole grains, poultry, fish, nuts, and legumes had greater mean BMD and BMC. In contrast, in the TA group, dietary pattern with lactose-free and gluten-free products was associated with greater mean BMD and BMC. The latest studies have shown that adherence to the Mediterranean diet rich in olive oil, a high intake of fruit, vegetables, fish, and nuts, and a high proportion of phenols is protective against osteoporosis27. Lactose intolerance may predispose individuals to low calcium intake, but a study found no significant difference in calcium absorption from a range of dairy products differing in lactose levels in adult women54. Therefore, it can be concluded that the regular physical activity of women in the masters category also influences nutritional choices. In our study, regardless of sport discipline, more than 60% of women consumed dairy products. Compared to the data from the fourth wave (2011/2012) of the Survey of Health, Aging and Retirement in Europe55, this percentage is much greater than that of non-training women of a similar age. In our study, the number of dairy products consumed per day significantly influenced forearm BMD in connection with physical activity. Dairy products are the main food sources providing bone-beneficial nutrients, such as calcium, phosphorus and magnesium and also protein, vitamin B-12, zinc, potassium and riboflavin. These food sources provide a morphological role in bone healthy structure7. The dietary intake of nutrients, especially protein, calcium and vitamin D, is important for masters athletes because of the physiological changes that occur with aging and the unique nutritional needs associated with high levels of physical activity.

When analyzing the nutritional patterns of physically active women and their impact on BMD, it is necessary to mention potential confounding variables such as impaired absorption of dietary components, general health condition, heat treatment of food, and quality of food products.

Interactions between mean BMD and BMC and biological factors

In the masters population, progressive aging processes and age-related diseases may also be obstacles to accurate analysis. In this study, there were clear significant interactions between mean BMD and BMC and biological factors such as age at menarche and age at menopause. In all groups of women TA, EA and SPA late menarche determined higher mean BMD, especially in TA. Studies of the interaction of biological status and bone mineralization show divergent results, and most often involve women from the general, non-training population. In addition, studies show different relationships between the age of menarche and menopausal status on BMD at different skeletal locations3,31,32,33. One study found that postmenopausal women with a menarche age of ≥ 16 years had significantly lower lumbar spine BMD than that had by those with a menarche age of ≤ 12 years31. In the other research age at menopause did not influence the BMD of the lumbar spine or femoral neck. In this study age at menarche or menopause seems to be of limited or no importance as a risk factor for osteoporosis33. Our study of women training after the age of 40 showed that biological status significantly influenced forearm bone parameters. The surveyed women were physically active in the past, at the age of puberty and peak bone mass building, and now at the peri, pre-, and menopausal age, so this is also a specific group for analysis. Physical activity affects the menstrual cycle, and after the age of 40, it may improve the health and hormonal status of women. In a Polish study with middle-aged women (aged 40–65), high and moderate PA levels have less severe menopausal symptoms compared to inactive women56. Interactions of biological factors and bone mineral status in physically active women require further in-depth research.

Athletes in the masters category are excellent materials for testing the long-term effect of training on the mineral state of bones. As research and data collected from their life histories indicate, most of them were competitive athletes both in their youth and now. This study suggested that high-altitude osteogenic exercises, such as throwing, and weight-bearing exercises at a young age and training continuation later in life may be important contributors to BMD and BMC in middle-aged and elderly individuals. Physical activity in women over 40 years of age may also influence better eating patterns and more frequent consumption of healthier foods such as fruit, vegetables, dairy products, whole grains, poultry, fish, nuts, and legumes.

Strengths and limitations

Athletes in the masters category are excellent materials for testing the long-term effect of training on the mineral state of bones, in the general population it is very hard to find individuals with physical activity and sports almost in all life. The strength of the work is that the study was performed at a single point in time, with all participants tested and measured by a single specialist. This eliminated the subjective error of the measurements. Determinants of BMD were analyzed multivariate and in two ROIs. A thorough statistical analysis of the data was carried out. ANOVA helps identify the sources of variation in the data and provides a measure of the variability between groups. We used in analysis the degree of correlation of the predictors was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF) collinearity test, taking a not-to-exceed value of 10. Residual analysis was also performed, testing for homoscedasticity using the White test and the degree of correlation of the residuals using the Durbin-Watson test. Our study, although it includes the results of an elite group of women in the masters category, has some limitations. One limitation of the full interpretation of the results of the study is the relatively small number of female athletes studied after participating in the sports competition. BMD accounts for almost 70% of bone strength and bone quality accounts for the remaining 30%, therefore, it is worth extending this research to include bone quality characteristics. The one of the limitations of this study can be the study’s homogeneity (Caucasian, European origin) limits the applicability of findings to broader populations, and exclusion criteria may restrict results to specific athlete groups.

Summary and conclusions

Physical activity at the masters age helps maintain bone mineralization and may influence dietary choices. The long-term effects of athletic training, especially exercises such as throwing, have been confirmed in these studies. It is therefore worth considering popularizing these exercises at every stage of ontogenesis as a supplement to any other physical activity. Athletic training after the age of 40 can help eliminate the risk of developing osteoporosis. Dietary patterns, particularly those based on the consumption of dairy products, vegetables, fish, poultry, nuts and legumes, are important determinants of BMD and BMC among female masters trainers. Interactions of biological factors and bone mineral status in physically active women require further in-depth research. The findings underscore the need for personalized training and nutritional approaches for elite female athletes to support bone health, with a call for further longitudinal studies to assess long-term impacts.

The results and conclusions of this study have practical, applied uses for both coaches and Masters athletes. They can serve as practical guidance as to what factors particularly related to diet are important for the bone health of athletes.

Future Research Directions: a further investigation into biological factors to BMD in Masters athletes women, extending the scope of the study to include other sports disciplines with different OI in the masters category, including analyses of bone turnover markers and other biochemical tests to assess bone metabolism.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMC:

-

Bone mass

- BMD:

-

Bone mineral density

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- DIS:

-

Distal part of forearm

- EA:

-

Endurance athletes

- FFQ:

-

Food frequency questionnaire

- FM:

-

Fat mass

- FFM:

-

Fat-free mass

- OI:

-

Osteogenic index

- PBF:

-

Percentage of body fat

- PROX:

-

Proximal part of forearm

- SPA:

-

Speed-power athletes

- TA:

-

Throwing athletes

References

Buttan, A. et al. Physical activity associations with bone mineral density and modification by metabolic traits. J. Endocr. Soc. 4 (8), 1–11 (2020).

Vlachopoulos, D. et al. The impact of sport participation on bone mass and geometry in male adolescents. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 49 (2), 317–326 (2017).

Kopiczko, A. Determinants of bone health in adults polish women: The influence of physical activity, nutrition, sun exposure and biological factors. PLoS One 15(9), e0238127 (2020).

Koedijk, J. B. et al. Sedentary behaviour and bone health in children, adolescents and young adults: a systematic review. Osteoporos. Int. 28, 2507–2519 (2017).

Rodríguez-Gómez, I. et al. Associations between sedentary time, physical activity and bone health among older people using compositional data analysis. PLoS One 13(10), e0206013 (2018).

Christofaro, D. G. D. et al. Comparison of bone mineral density according to domains of sedentary behavior in children and adolescents. BMC Pediatr. 22 (1), 72 (2022).

Muñoz-Garach, A., García-Fontana, B. & Muñoz-Torres, M. Nutrients and dietary patterns related to osteoporosis. Nutrients 12 (7), 1986 (2020).

Levis, S. & Lagari, V. S. The role of diet in osteoporosis prevention and management. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 10, 296–302 (2012).

Thompson, M. J. W. et al. The relationship between cumulative lifetime ultraviolet radiation exposure, bone mineral density, falls risk and fractures in older adults. Osteoporos. Int. 28 (7), 2061–2068 (2017).

Liu, Y., Jin, G., Wang, X., Dong, Y. & Ding, F. Identification of new genes and loci associated with bone mineral density based on Mendelian randomization. Front. Genet. 12, 728563 (2021).

Noel, S. E., Santos, M. P. & Wright, N. C. Racial and ethnic disparities in bone health and outcomes in the united States. J. Bone Min. Res. 36 (10), 1881–1905 (2021).

Kopiczko, A. Bone mineral density in the various regions of the skeleton in women with subclinical hypothyroidism: the effect of biological factors, bone turnover markers and physical activity. Biomed. Hum. Kinet Vol. 16 (1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.2478/bhk-2024-0001 (2024).

Daly, R. M. et al. Gender specific age-related changes in bone density, muscle strength and functional performance in the elderly: a-10 year prospective population-based study. BMC Geriatr. 13, 71 (2013).

Bellver, M., Del Rio, L., Jovell, E., Drobnic, F. & Trilla, A. Bone mineral density and bone mineral content among female elite athletes. Bone 127, 393–400 (2019).

Hart, N. H. et al. Biological basis of bone strength: anatomy, physiology and measurement. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 20 (3), 347–371 (2020).

Gómez-Cabello, A., Ara, I., González-Agüero, A. & Casajús, J. A. Vicente-Rodríguez, G. Effects of training on bone mass in older adults: a systematic review. Sports Med. 42 (4), 301–325 (2012).

Bolam, K. A., van Ufelen, J. G. & Taafe, D. R. The effect of physical exercise on bone density in middle-aged and older men: a systematic review. Osteop Int. 24 (11), 2749–2762 (2013).

Kopiczko, A. Factors affecting bone mineral density in young athletes of different disciplines: a cross-sectional study. Arch. Budo Sci. Martial Art Extreme Sport 19, 75–84 (2023).

Herrmann, M. et al. Interactions between muscle and bone-where physics Meets biology. Biomolecules 10 (3), 432 (2020).

Milanese, C., Cavedon, V., Corradini, G., Rusciano, A. & Zancanaro, C. Long-term patterns of bone mineral density in an elite soccer player. Front. Physiol. 12, 631543 (2021).

Jacobs, D. R. Jr, Gross, M. D. & Tapsell, L. C. Food synergy: an operational concept for Understanding nutrition. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 89 (5), 1543–1548 (2009).

Sahni, S., Mangano, K. M., McLean, R. R., Hannan, M. T. & Kiel, D. P. Dietary approaches for bone health: lessons from the Framingham osteoporosis study. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 13 (4), 245–255 (2015).

Tucker, K. L. et al. Bone mineral density and dietary patterns in older adults: the Framingham osteoporosis study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 76 (1), 245–252 (2002).

Benetou, V. et al. Mediterranean diet and hip fracture incidence among older adults: the CHANCES project. Osteoporos. Int. 29, 1591–1599 (2018).

Shen, C. L. et al. Fruits and dietary phytochemicals in bone protection. Nutr. Res. 32, 897–910 (2012).

Rivas, A. et al. Mediterranean diet and bone mineral density in two age groups of women. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 64, 155–161 (2013).

Zupo, R. et al. Association between adherence to the mediterranean diet and Circulating vitamin D levels. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 1–7 (2020).

Chuang, T. L., Lin, C. H. & Wang, Y. F. Effects of vegetarian diet on bone mineral density. Tzu Chi Med. J. 33 (2), 128–134 (2020).

Garofalo, V. et al. Effects of the ketogenic diet on bone health: A systematic review. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14, 1042744 (2023).

Rizzoli, R. Dairy products and bone health. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 34 (1), 9–24 (2022).

Yang, Y., Wang, S. & Cong, H. Association between age at menarche and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 18 (1), 51 (2023).

Sioka, C. et al. Age at menarche, age at menopause and duration of fertility as risk factors for osteoporosis. Climacteric 13 (1), 63–71 (2010).

Gerdhem, P. & Obrant, K. J. Bone mineral density in old age: the infuence of age at menarche and menopause. J. Bone Min. Metab. 22 (4), 372–375 (2004).

Lee, J. J. et al. Age at menarche and risk of cardiovascular disease outcomes: findings from the National heart lung and blood Institute-sponsored women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8(12), e012406 (2019).

Fuhrman, B. J. et al. Association of the age at menarche with site-specific cancer risks in pooled data from nine cohorts. Cancer Res. 81 (8), 2246–2255 (2021).

Lewiecki, E. M. et al. Best practices for Dual-Energy X-ray absorptiometry measurement and reporting: international society for clinical densitometry guidance. J. Clin. Densitom. 19 (2), 127–140 (2016).

Hall, J. G., Allanson, J. E., Gripp, K. W. & Slavotinek, A. M. Handbook of Physical Measurements (Oxford University Press, 2007).

Marques, P., Madeira, T. & Gama, A. Menstrual cycle among adolescents: girls’ awareness and influence of age at menarche and overweight. Rev. Paul Pediatr. 40, e2020494 (2022).

Bubach, S. et al. Impact of the age at menarche on body composition in adulthood: results from two birth cohort studies. BMC Public. Health. 16 (1), 1007 (2016).

O’Connor, K. A., Holman, D. J. & Wood, J. W. Menstrual cycle variability and the perimenopause. Am. J. Humm Biol. 13, 465–478 (2001).

Fabiani, R., Naldini, G. & Chiavarini, M. Dietary patterns in relation to low bone mineral density and fracture risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv. Nutr. 10, 219–236 (2019).

Grissom, R. J. & Kim, J. J. Effect sizes for research: Univariate and multivariate applications (2nd ed) (Routledge, 2012).

Wiegandt, Y. L. et al. The relationship between volumetric thoracic bone mineral density and coronary calcification in men and women - results from the Copenhagen general population study. Bone 121, 116–120 (2019).

Pinheiro, M. B. Evidence on physical activity and osteoporosis prevention for people aged 65 + years: A systematic review to inform the WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 17, 150 (2020).

Han, H. et al. Association between muscle strength and mass and bone mineral density in the US general population: data from NHANES 1999–2002. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 18 (1), 397 (2023).

Piasecki, J. et al. Hip and spine bone mineral density are greater in master sprinters, but not endurance runners compared with non-athletic controls. Arch. Osteoporos. 13 (1), 72 (2018).

Ireland, A. et al. Greater maintenance of bone mineral content in male than female athletes and in sprinting and jumping than endurance athletes: a longitudinal study of bone strength in elite masters athletes. Arch. Osteoporos. 15, 87 (2020).

Kopiczko, A., Adamczyk, J. G., Gryko, K. & Popowczak, M. Bone mineral density in elite masters athletes: the effect of body composition and long-term exercise. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 18 (1), 7 (2021). Erratum in: Eur Rev Aging Phys Act. 18(1):13 (2021).

Hannam, K. et al. Habitual levels of higher, but not medium or low, impact physical activity are positively related to lower limb bone strength in older women: findings from a population-based study using accelerometers to classify impact magnitude. Osteoporos. Int. 28 (10), 2813–2822 (2016).

Akai, K. et al. Association between bone quality and physical activity in community-dwelling older adults. Geriatrics (Basel) 9 (3), 62 (2024).

Lim, C. L. et al. The effects of community-based exercise modalities and volume on musculoskeletal health and functions in elderly people. Front. Physiol. 14, 1227502 (2023).

Erickson, K. R., Grosicki, G. J., Mercado, M. & Riemann, B. L. Bone mineral density and muscle mass in masters olympic weightlifters and runners. J. Aging Phys. Activity. 28 (5), 749–755 (2020).

Benedetti, M. G., Furlini, G., Zati, A. & Letizia Mauro, G. The effectiveness of physical exercise on bone density in osteoporotic patients. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 4840531 (2018).

Hodges, J. K., Cao, S., Cladis, D. P. & Weaver, C. M. Lactose intolerance and bone health: the challenge of ensuring adequate calcium intake. Nutrients 11 (4), 718 (2019).

Ribeiro, I. et al. Dairy product intake in older adults across Europe based on the SHARE database. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 38 (3), 297–306 (2019).

Dąbrowska-Galas, M., Dąbrowska, J., Ptaszkowski, K. & Plinta, R. High physical activity level May reduce menopausal symptoms. Medicina (Kaunas) 55 (8), 466 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K., J.G.A., and K.G. conceptualized and supervised the study. A.K. and J.G.A methodology and research organization. A.K. statistical analysis. J.B., J.G.A., K.G formal analysis. A.K., J.B., M.N. investigation. J.B. and M.N. data curation. A.K., J.G.A., K.G., J.B., and M.N. writing original draft preparation. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The project complies with the principles of bioethics, as confirmed by the Bioethics Committee of the National Institute of Public Health, National Institute of Hygiene in Warsaw (protocol number 1/2021). The work was carried out by the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for experiments involving humans. All individual participants provided information.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kopiczko, A., Bałdyka, J., Adamczyk, J.G. et al. Association between long-term exercise with different osteogenic index, dietary patterns, body composition, biological factors, and bone mineral density in female elite masters athletes. Sci Rep 15, 9167 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93891-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93891-9