Abstract

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) analysis of single cells, especially nonadherent, is inherently slow and analysis-heavy. To address the inherent difficulty of measuring individual cells, and to scale up toward a large number of cells, we take a two-fold approach; first, we introduce an easy-to-fabricate reusable poly(dimethylsiloxane)-based array that consists of micron-sized traps for single-cell trapping, second, we apply a deep-learning method directly on the extracted curves to facilitate and automate the analysis. Our approach is validated using suspended cells, and by applying a small compression with a tipless cantilever AFM probe, we investigate the effect of various cytoskeletal drugs on their deformability. We then apply deep learning models to extract the elasticity of the cell directly from the raw data (with a Coefficient of Determination of 0.47) as well as for binary (with an Area Under the Curve score of 0.91) and multi-class classification (with accuracy scores exceeding 0.9 for each drug). Overall, the versatility to fabricate the microwells in conjunction with the automated analysis and classification streamline the analysis process and demonstrate their ability to generalize to other tasks, such as drug detection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-throughput assays are essential during drug discovery and development processes. Traditionally, high-throughput screening (HTS) involves the screening of a very large number (thousands) of compounds or potential drugs to identify those with the desired characteristics1,2. Cell-based assays, unlike HTS or biochemical assays, provide on the other hand high-content information as they involve cultured cells as model systems to assess the effects of drugs on cellular functions1. These assays can measure various parameters, such as cell viability, proliferation, apoptosis, gene expression, protein activity, and cellular response to stimuli hence yielding insights into the efficacy, toxicity, and mechanisms of action of potential drugs3.

Atomic Force microscopy (AFM), offering high-resolution imaging and nanoscale mechanical characterization has been broadly used for single-cell studies3,4,5. Applications of single-cell AFM range from fundamental understanding of cellular processes to identifying disease mechanisms, to screening potential therapeutics6. Cell elasticity, for example, has been linked to a number of physiological conditions, such as cancer, where a more elastic cell may indicate metastasis6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Similarly, a number of determinations can be made from the elastic modulus of white blood cells, including the destiny of differentiating HL60 cells or the activation state of neutrophils13,14. In particular, the cell cortex is a thin layer of cytoplasm located beneath the plasma membrane that contains actin filaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments15,16. It plays a crucial role in regulating cell mechanics by generating cortical tension, which in turn regulates cell shape, movement, division, and tissue morphogenesis17,18,19,20,21. Cortical tension is primarily generated by actomyosin contractility, where myosin II motors contract actin filaments15,22,23. The activity of myosin II is regulated by Rho kinase (ROCK), which activates myosin light chain kinase (MLCK), leading to the phosphorylation and activation of myosin II. Recent research has made significant progress in understanding how the composition and organization of the cell cortex interplay to control mechanotransduction24.

When it comes to drug testing, cells exposed to different drugs or concentrations of drugs can be assessed through AFM to elucidate the drug’s impact on cellular physiology at the single-cell level. Typically, an AFM probe is used to impose controlled forces and measure the resulting indentation depth from the sample surface, a technique known as nanoindentation25. The effect of drugs or other factors on the mechanical properties of subcellular structures such as the cell membrane or the nucleus can be thus elucidated26. Its applications in these areas contribute to our understanding of cellular processes, disease mechanisms, and the evaluation of potential therapeutics27,28.

AFM, while straightforward and routinely used in the characterization of adherent cells, becomes rather challenging with non-adherent cells due to the tendency of the cell to move laterally during indentation29. The use of a symmetrical array of microscale wells trapping non-adherent cells into a known pattern, greatly facilitates the application of nanoindentation without the concern of cell slippage, while also opening the possibility of an automation algorithm to probe the array of known locations and significantly reducing the labor cost of AFM data collection5. Another labor-intensive aspect of AFM is the subsequent data analysis, which is rather tedious requiring fitting the acquired curves to well-adapted known models in order to extract meaningful values, i.e., the Young’s modulus5,30. The use of machine learning (ML) in handling and analyzing AFM data allows to adapt to the complex, nonlinear nature of such data, effectively handling noise and capturing subtle variations in mechanical properties. Moreover, once trained, ML models can deliver rapid predictions, significantly reducing the time required for comprehensive AFM data analysis.

Recently, several studies have employed ML and deep learning (DL) methods to analyze AFM data for various purposes, such as characterizing breast cancer cell mechanics31, detecting bladder cancer cells32,33, diagnosing cancer tissue34 and identifying variations between cancer cells with varying levels of neoplastic aggressiveness35. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), for example, have been instrumental in processing such data36, enabling the extraction of valuable insights that could not be exposed through conventional methods. CNNs are widely recognized deep neural networks that utilize stacks of convolutional and pooling layers to acquire spatial information and progressively learn complex feature representations of the input (raw) data37. As a result, they have demonstrated remarkable success in several domains, including computer vision and natural language processing38.

In this work, a simple method to develop a poly(dimethylsiloxane)-PDMS microwell array comprising cell-sized traps is proposed, as schematically shown in Fig. 1a. The size of the wells can be easily adjusted based on the cells to be studied. Herein, the microarray is used for the capture and mechanical screening of non-adherent cells (T-cells) via AFM compression before and after treatment with a variety of cytoskeletal drugs. Jurkat’s T-cells are widely available, well characterized, and their elasticity was previously investigated by the authors39. This platform could be used in conjunction with a programmable AFM stage to automate the measurement. Finally, we have employed a comprehensive pipeline that integrates ML and DL models to fully exploit the cell-array-related information inherent in our AFM data. We have developed a model capable of directly predicting Young’s modulus values from the raw AFM data, using a custom CNN and assessed its accuracy using a Leave-One-Sample-Out cross-validation regression approach. Additionally, to fully harness the AFM-related features learned by the CNN regressor, we extracted feature maps from the CNN’s final layer and employed them as inputs for two well-established machine-learning classifiers: Random Forest and Support Vector Machine. This allowed us to detect the presence of drugs and identify specific drug types using a nested Leave-One-Sample-Out cross-validation classification framework. Finally, we have implemented two distinct techniques for exploring and visualizing the feature maps that our models have learned, i.e., the Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) and the t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE).

Overall, this study demonstrates a reliable and versatile platform technology towards automating single-cell analysis using AFM compression, as showcased for the challenging case of non-adherent cells. We have chosen cell elastic modulus as the figure of merit for this work, and we have tested our method using three drugs known to affect the cytoskeleton, inducing changes to the elasticity of the cell. Our data were used to train our models resulting in precisely predicting Young’s modulus, as well as detecting the presence of drugs and recognizing the specific drug type with excellent accuracy. By adjusting the size of the microwells, a variety of sizes/types of cells can be captured, and using the same analysis method (with small adjustments) provides altogether an integrated analysis in line with drug testing industry requirements.

Materials and methods

Fabrication of the microwell array

Cell traps were designed in AutoCAD 2022 Software (Autodesk Inc. San Francisco, CA), then printed in SU-8 (Kayaku Advanced Materials, Westborough, MA) on a 500 µm Si wafer (University Wafer, Boston, MA), using a Kloe Dilase 250 maskless lithography system (Kloe, Treviers, France). The SU-8 served as a high-durability etch mask, and permanent patterns were etched into the silicon via Deep Reactive Ion Etch (DRIE) on a Plasmalab 100 system (Oxford Instruments Plasma Technology, Bristol, UK). Previous experiments showed that using a more standard positive photoresist e.g., AZ1518, or even a very thick resist e.g., AZ9260 yielded unpredictable results due to nonspecific etching and eventual removal of the resist. Given its significant thickness (100 µm) and high etch tolerance of the crosslinked polymer, SU-8 is an effective etch mask for deep etches of 300 µm or more40. Once the SU-8 mask was patterned, the Si wafer was transferred to an Oxford Instruments Plasmalab 100 for DRIE. Etching was achieved through a Bosch process using SF6 and C4F8 process gasses (alternating process: C4F8 1750W ICP, 5W bias; SF6 1750W ICP, 25W bias), obtaining a final depth of 5 µm. The SU-8 mask was removed with adhesive tape, and the wafer was returned to the plasma chamber for a 20-second exposure to C4F8 plasma to produce a hydrophobic thin film at the surface, facilitating the removal of cured PDMS. The wafer was subsequently cleaved into individual 1 cm stamps. PDMS was patterned by placing a drop of liquid PDMS (10:1 base to crosslinker, Sylgard 184, Corning Inc. Corning, New York) onto a glass slide, then pressing it with the patterned stamp and allowing it to cure on a hot plate, at 100C. Removing the stamp yielded the final device, an array of 5 µm deep traps on the glass substrate. The small volume of PDMS fully cures in a short period, allowing the mold to be peeled off with no damage to the microstructure of the individual traps (Fig. 1b,c). The resulting microwells (prepared by direct laser writing) were roughly 5 µm in depth and 12 µm in width (Fig. 1d) and generally circular with some minor asymmetry, (a result of the laser spot size relative to the pattern size). After curing the PDMS, the microwell array remains strongly hydrophobic, thus unsuitable for cell culture as-is. The devices are hence exposed to an oxygen plasma (20 W for 20 sec, 1000 mT), rendering the surface hydrophilic. The hydrophilic PDMS array is readily populated by cell-dense media, and single cells spontaneously settle within the traps.

Cell-culture

Jurkat T cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) derived from a male subject with T-cell leukemia were used for all experiments. Cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium containing 4.5 g/L D-glucose (hyperglycemic amount), 2.383 g/L 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 0.3 g/L L-glutamine, 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, and 0.11 g/L sodium pyruvate (Gibco, Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Biosera, Nuaille, France). Cells were incubated at \(37^{\;\circ }\)C and 5% \(CO_2\). Drug-treated cells were incubated with the drug for 24 hours in a flask, then the cells and drug-treated media were extracted by pipette, and dropped into the cell traps immediately prior to AFM measurement. Drugs were incubated at the following concentrations: Y-27632: 20 µM; Blebbistatin: 1 µM; Cytochlasin B: 1 µM. These are biologically relevant concentrations to induce cytoskeletal changes without toxicity.

Live cell AFM

Force curves were collected using the Asylum MFP-3D Origin AFM system to analyze the mechanical characteristics of cells. The AFM probes characteristics are: Tipless Silicon Nitride PNP-TR-TL, Triangle, 0.08 N/m, L × W × T = 200 × 28 × 5 µm. A precise determination of the probe spring constant was carried out using the thermal tune method. Subsequently, compression force curves were generated at a constant velocity of 1.98 µm/s and a force threshold of 5nN to assess the elastic behavior of the cells being investigated.

Cells in suspension were transferred by pipette from a flask and dropped onto the plasma-treated cell trap substrate. The substrate was transferred to the heated stage of the AFM, and allowed to incubate for several minutes while cells settled into traps due to gravity. Once cells had settled ( 5 mins), AFM measurements commenced. Atomic force microscopy was conducted on an Asylum MFP-3D (Oxford Instruments Asylum Research, Oxford, UK) equipped with a BioHeater chamber. We have used 5 cells for each condition, 7 measurements on each cell. All the tested cells were immersed in RPMI medium, at the fixed temperature of \(37^{\;\circ }\)C. The AFM probe was first positioned above a cell sitting in the micro-well, assisted by the AFM system’s built-in optical microscope. Then the AFM probe was brought into contact with the cell and pressed repeatedly. Meanwhile, the relation between force (F) and deformation (d) of the cell, was measured by the AFM system.

Data analysis

AFM data was exported to Microsoft Excel, where it was analyzed by a parallel plate compression model adapted from15. The deformation of a cell can be calculated by the following equation: d=D-\(\delta\). Where D refers to the displacement of the base of the AFM probe, \(\delta\) refers to the deflection of the AFM tip. The force F can be calculated by the following equation F=k\(\times\) \(\delta\). Cortex tension is calculated from the slope of the linear portion of the AFM cantilever deflection curve (where Z-\(\delta\) is less than 600 nm) using Eq. (1); and finally, Young’s modulus is calculated using Eq. (2), see15 for details and derivation. For these calculations, an average diameter of 12 µm was used, and a cortical thickness of 200 nm. For Eqs. (1) and (2), T is the surface tension, \(k_c\) is the calibrated spring constant of the AFM probe, Z is the vertical displacement of the stage, d is the cantilever deflection, E is the Young’s modulus, R is the cell radius, h is the cortex thickness (200 nm).

Machine learning

The ML procedures were implemented using Python libraries, including TensorFlow41, Keras42, and sci-kit-learn43. For training the DL models, we utilized a Google Colab Pro subscription, which provided access to a powerful A100 GPU with 40 GB of VRAM. Additionally, model interpretation and other ML tasks were carried out on an HP Victus 16 laptop featuring an 11th Gen Intel Core i7 processor clocked at 2.3 GHz, 32 GB of RAM, and running the Windows 11 operating system. Computation was further accelerated by the presence of an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 GPU with 6 GB of VRAM.

Regression

A custom CNN architecture was designed to optimally fit our problem. The employed CNN consists of three layers. The first layer includes a convolutional layer, followed by a batch normalization layer and a Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function. Following, the other two layers consist of a convolutional layer, followed by a batch normalization layer, a ReLU activation function, and a 2 × 2 max-pooling layer. The convolutional layer has 32, 128, and 128 filters with kernel sizes of 8 × 8, 3 × 3 and 5 × 5, respectively. Consequently, data are flattened and fed to a fully connected module of two layers with 128 and 1 node(s). After the flattening and the first fully connected layers, a dropout layer is added, with dropout rates of 0.081 and 0.168, respectively. For compiling the model, the mean absolute error loss and the Adadelta optimizer are used. Moreover, an early stopping criterion that terminates the training process if the validation loss does not improve for 30 consecutive epochs, is employed. The maximum number of epochs is set to 600. For the evaluation of the model, a Leave One Sample Out (LOSO) cross-validation is adopted in order to get realistic results and avoid overfitting issues. In LOSO cross-validation, the dataset is divided into N subsets, where N represents the number of samples in the dataset. Each subset contains all but one sample from the original dataset. The model is then trained N times, with each iteration using N-1 samples for training and the remaining single sample for testing. The testing sample is left out or withheld from the training set, and the model’s performance is evaluated based on how well it predicts this held-out sample. It should be noted that during the training, the training set is further divided into training (87.5%) and validation (12.5%) sets. Hence, the training set is used to train the model, while the validation set aids the model to stop at the epoch of maximum generalization ability. Almost all the aforementioned parameters i.e., number of convolutional layers, use of max-pooling layer, number and size of filters in each layer, number of nodes in the fully connected layer, dropout rates, and learning rate have been decided through Bayesian optimization44.

Classification

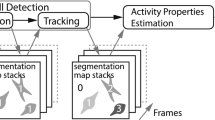

As can be seen in Fig. 2d, after the training is complete, the feature map of the last layer of the CNN is extracted. Thus, during the LOSO cross-validation, when testing the model on the held-out sample the feature map that corresponds to each sample is saved. Therefore, a new table representation of the input data is created. The size of this table is NxM, where N is the number of samples and M is the number of features. Consequently, this table is presented to two ML classifiers i.e., SVM45 and RF46. With this approach we aim to solve two different problems: (1) a binary classification problem where the models try to detect the presence of the drug and (2) a multi-class classification problem where the models aim to detect both the presence of the drug and the drug type.

For the evaluation of our models, a nested LOSO cross-validation scheme is adopted47 for both the binary and the multiclass classification scenarios. Inside each outer LOSO loop, a standardization scaling is applied, followed by the Extra Trees feature selection method. Consequently, in the inner 5-fold cross-validation loop a grid search is implemented to tune the models’ hyper-parameters. Nested cross-validation is considered the most reliable and unbiased method to assess the predictive ability of the classifiers48. More specifically, in the employed nested LOSO cross-validation classification scheme, the dataset is divided into several N outer folds in the outer loop, where N is the number of samples. Within each outer fold, a grid search is conducted to systematically test different combinations of hyperparameters for the ML model. Simultaneously, an inner cross-validation loop is employed within each outer fold. This inner loop further divides the data into five folds, allowing for model training and validation with the specific hyperparameters under consideration. This process is repeated for each combination of hyperparameters tested in the grid search, and the optimal set of hyperparameters for the current outer fold is determined based on the performance averaged across the inner folds. Regarding the SVM implementation, a radial basis function kernel was utilized. The grid search approach was employed to determine optimal values for the regularization parameter C and the kernel coefficient gamma. The grid for both C and gamma consisted of the following values: 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100. Furthermore, in the case of RF, a grid search approach was employed, considering different values for the number of estimators and the maximum depth. The grid search involved testing combinations of 50, 100, 200 for the number of estimators, 2, 3, 4, 5 for the minimum number of samples to perform a new split, and 1, 2, 3, 4 for a minimum number of samples required in a terminal leaf node.

Results visualization

Model interpretation and data visualization are very important in understanding the results of ML models. More specifically, in CNNs model interpretation can be achieved through the Grad-CAM algorithm49. Grad-CAM operates by generating a heatmap that highlights the regions within an input image that are most influential in determining the network’s final classification decision. This is achieved by computing the gradients of the network’s output with respect to the feature maps in a chosen convolutional or activation layer. These gradients provide insights into the importance of each feature map, and Grad-CAM combines them to produce a weighted sum that emphasizes the crucial image regions. By displaying this heatmap side by side with the original image, we can gain useful insights regarding which parts of the input image were most significant in the model’s decision. In this study, the heatmaps of all the convolutional and activation layers were averaged together in order to integrate information from different depths of the network.

Furthermore, the visualization of feature maps at the final layer of a CNN proves highly beneficial, as it provides useful insights into the structure and quality of these feature maps. Nevertheless, feature maps in the last layer of a CNN tend to be high-dimensional, making their visualization challenging. To address this challenge, t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) serves as a powerful tool. t-SNE operates by reducing the dimensionality of the data while preserving the relative distances between data points. It accomplishes this by iteratively optimizing a probability distribution that aligns the similarities in the high-dimensional space with those in the low-dimensional space. As a result, t-SNE can effectively transform complex high-dimensional feature maps into a more manageable form for visualization and analysis, aiding in the interpretation and understanding of CNN representations. In this study, a grid search approach was employed to fine-tune this parameter. Specifically, the algorithm was tested with a range of values between 5 and 50, as recommended by the algorithm’s developers. For each value within this range, the silhouette score was calculated to find the perplexity value that offers the best separation between the examined classes. Finally, to maintain consistency with the classification experiments and to mitigate the challenges posed by the curse of dimensionality, we applied the same feature selector used within the nested LOSO cross-validation procedures to filter out less informative features.

Results and discussion

Easy-to-fabricate multiple-use microwell array for single cell-trapping

The microwell array was fabricated using a simple and reproducible method based on a photolithographically patterned silicon mold. Our fabricated mold is robust and can be in turn used to fabricate numerous polymer arrays with unaffected precision and without the need to use time-consuming methods for the development of the chip. For the fabrication of the PDMS traps, a silicon stamp was used for molding the traps to ensure high reproducibility and uniformity (Fig. 1a). A few studies have taken a similar approach to the fabrication of microwell arrays29,50,51,52 based on SU-8 molds, however, our method addresses some of the issues that typically arise when producing such chips. SU-8 patterning is a well-established method of structuring PDMS, however, it is prone to delamination with repeated use, and when used as a final structure, the production is significantly more time-consuming than our simple stamp method. Furthermore, the Si mold is completely rigid and impervious to deformation under pressure, which could potentially be an issue when using a soft stamp e.g., PDMS. The stamp and cure production method allows for single, or multiple, arrays of microwells to be patterned on microscope slides, cover glass, or any other substrate, with a total production time of less than 5 minutes per array (Fig. 1b,c). The stamps are suitable for multiple uses (>50), without the risk of delamination as would be present in an SU-8 mold. The resulting microwells were roughly 5 \(\mu\)m in depth and 12 \(\mu\)m in width (Fig. 1d) and generally circular with some minor asymmetry, a result of the laser spot size relative to the pattern size.

(a) Schematic representation of the critical steps followed to produce the micro-well array: The fabrication of the reusable Si mold using photolithography and subsequent DRIE for sub-micron resolution in three dimensions and precise control of trap geometry. Finally, the traps are produced by stamping PDMS onto a glass substrate. The process can be completed in under a minute and allows highly reproducible structures. SEM images of (b) the Si mold (c) one individual trap-mold and (d) one individual PDMS cell trap (structures are 15 µm wide, 5 µm tall for gravitational capture and positioning of non-adherent cells for AFM measurements).

Measuring cell elasticity via live cell AFM

Prior to any measurement, the stability of our system i.e., the ability to maintain the media without evaporation for the duration of the measurements, was validated given the small size of the wells. The results as shown in Fig. S1, suggest a comfortable time window of 24 h prior to media evaporation which exceeds by far the measurement time scales. In a typical experiment, the microwell arrays are placed onto the AFM stage, and cells are pipetted on top as schematically depicted in Fig. 2a. The stage is kept at \(37^{\;\circ }\)C and submerged via periodic addition of fresh media. Substrates were replaced at regular intervals to avoid the buildup of salt, and no time-based trends were observed during measurements (see Fig. S3). After allowing a few minutes for the cells to settle, we observe the cells filling the traps as shown in the confocal image of Fig 2b as well as a significant number of them resting on the substrate as a result of the homogeneous treatment of the chip. Cell density was low enough that nearby cells did not interfere with measurements (significantly lower than indicated in Fig. 2b). Interference from neighboring cells, or motion of the target cell resulted in major irregularities in the AFM curves, however, these data represent a small proportion of the dataset and were discarded (see examples in Fig. S2a–k for good and discarded datasets). Traps are purposely designed to be slightly larger than the 12 µm diameter T-cells, but not large enough to accommodate more than a single cell. A small number of wells contained multiple cells, and were not used for measurements. The AFM probe is manually positioned over each cell using an optical microscope in conjunction with the AFM stage and the cells are compressed with the AFM cantilever to obtain a force-distance curve as shown in Fig. 2c. We have used a flat, tipless AFM probe with an angle of approximately 10 degrees. As demonstrated previously this angle has no significant effect upon the measurements within the constraints of the study, namely at low compression15. This step is repeated for multiple cells, across 4 conditions: control (prior to drug treatment) and after incubation with three different cytoskeletal drugs that are known to induce changes to the elasticity of the cells. The cell traps prevent non-adherent cells from sliding facilitating the collection of the AFM data without interfering with the motion of the cantilever or exerting excessive force on the cells, as might be possible if the cell was clamped or otherwise forcibly confined.

(a) Schematic representation of T-cells trapped in PDMS microwells, measured by tipless AFM cantilever. (b) Cells positioned in traps: Cells are labeled with Alexa Fluor. (All cells are labeled, and the trapped cells are highlighted using the software). (c) Typical indentation/ retraction curve produced by deflection of AFM cantilever vs vertical position of AFM stage (and the equation used to extract the young’s modulus E from the indentation curve). (d) Schematic representation of the ML process applied for the prediction and classification based on the AFM data.

(a) Schematic representation of the drug treatment with the structures of the three cytoskeletal drugs, added and (b) The calculated mean T cell cortex young’s modulus (E) under the different conditions based on the AFM cantilever deflection curve and the model applied. A total of 16-31 measurements were performed per condition.

The addition of the cytoskeletal drugs cytochalasin-B, Y-27632, and blebbistatin resulted in a decrease in Young’s modulus of 15%, 36%, and 47% respectively. These values were obtained by modeling cell compression between the tipless cantilever and substrate as a parallel plate system (Table 1, and Fig. 3a,b). Several drugs can target the cytoskeleton and affect cell cortex elasticity. For instance, cytochalasin B disrupts actin filaments by binding to the barbed end of the filament and inhibiting further polymerization, thereby reducing cell cortical elasticity53,54. In contrast, Y-27632 inhibits ROCK, reducing cell cortical elasticity by decreasing actomyosin contractility55. Moreover, blebbistatin inhibits myosin II activity by binding to the myosin ATPase domain and preventing ATP hydrolysis which might cause the reduction of cell cortical elasticity56. In our study, we observed a significant reduction in cortical elasticity of T-cells with all drugs, with a more substantial effect when inhibiting cell contractility by using Y-27632 and Blebbistatin. Based on their mechanism of action described previously, we expect that inhibiting actomyosin contractility to have a more potent effect on reducing cell cortex elasticity than Cytochalasin B, which is also confirmed by our results.

Automating and enriching AFM analysis using machine learning

We herein employ the use of ML and DL, that is CNNs, for processing the AFM data curves in order to fully automate the analysis. Following, we employ a regression model to predict the elastic modulus values directly from the raw data, as well as ML classifiers to determine whether a cell has been exposed to drugs, and which specific type of drug (see Figs. S4 and S5). As illustrated in our approach (Fig. 2d), we fill the area of the AFM curve (deflection vs. position) to increase the number of non-zero pixels. Notably, this filling process was applied purely as a preprocessing step to enhance the model’s performance, convergence speed and stability, and is not intended to alter the interpretation of the original measurement. The preprocessed images are then fed into a CNN, which is connected to a fully connected regression module consisting of a linear layer. The input size of this layer matches the number of elements in the CNN’s output, while the output size is one. After training, the images are passed through the CNN again to extract informative features. These features are abstract representations derived from the input images, expressed as numerical values produced by the model’s final layer. Following this, we present the extracted features to Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifiers, which classify each image into one of four categories: Control, Cytochalasin-B, Y-27632, or Blebbistatin. This approach aligns with recent research that employs AFM data curves for medical applications57,58. The results of our regression model are shown in Table 1. It is evident that there is quite a good agreement between the measured Young’s modulus values and the predicted ones with the mean value of the predicted values falling between the actual mean value ± one standard deviation, except for the case of Cytochalasin B (approximately two standard deviations higher than the true mean value). Furthermore, the 95% confidence interval of the predicted values is very small, compared to its corresponding value, highlighting the stability of our models over different initializations of the weights. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 4a–c, our regressors are highly efficient in predicting Young’s modulus values. In particular, Fig. 4a illustrates the Bland-Altman plot. The Bland-Altman plot is a graphical representation commonly used to assess the agreement or discrepancy between two measurements (in this case between the measured, via data curve fitting, and the predicted, via the CNN regression, Young’s modulus values). By visually examining the Bland-Altman plot, one can assess the overall agreement between the measured and the predicted values. If the points are scattered randomly around the mean difference line and the differences are evenly distributed within the limits of agreement, it suggests good agreement between the two measurements. Therefore, it is evident that there is an exceptionally good agreement between the baseline values and the predictions of our regressor. Moreover, the KS p-value that is reported on the plot refers to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test or goodness of fit. This compares the underlying distribution of a sample F(x) against the normal distribution G(x) and tests the null hypothesis that the two distributions are identical, F(x) = G(x) for all x. Hence, with a p-value of 0.161, we cannot reject the null hypothesis and thus, we can assume that our data are normally distributed. This observation justifies the selection of the limits at ± 1.96 × STD.

Illustration of the regression and classification results produced by the proposed DL pipeline. (a) The bland-Altman plot, (b) Scatter-plot between the measured (y-axis) and predicted (x-axis) values, (c) Accuracy plot showing the percentage of correct predictions over multiple classification thresholds. Binary and multiclass classification results produced by (d) the RF classifier and (e) SVM classifier.

Following, Fig. 4b illustrates a scatter plot between the measured (y-axis) and predicted (x-axis) values, together with the coefficient of determination (R-squared) and its square root (R). Although the resulting coefficient of determination i.e., 0.469, is considered moderate, the complexity of the task at hand and the existence of multiple conditions (control, Cytochalasin B, Blebbistatin, Y-27632) render it quite significant. This is also confirmed by Fig. 4c, where we plot the accuracy of our regressor over multiple thresholds. In essence, for each threshold, if the mean absolute error between the true and predicted value is less than the threshold, the prediction is considered correct and otherwise is considered wrong (Fig. 4c). These thresholds are defined as portions of the standard deviation of the measured Young’s modulus. The achieved accuracy is at approximately 90% when the threshold is one standard deviation and 100% for thresholds equal to or higher than two standard deviations. Overall, the aforementioned results showcase the efficiency of our DL regression model in precisely predicting Young’s modulus values.

As Fig. 2d shows, the feature map from the last layer of the CNN module is subsequently used as input for ML models, specifically RF and SVM, enabling two classification scenarios, i.e.: (a) binary classification to detect the presence of drugs, and (b) multiclass classification to identify both the absence and presence of drugs along with the different drug types, for the latter case. Figures 4d,e illustrate the classification results produced by the employed classifiers. In particular, the left panels depict the confusion matrix of the multiclass classification problem, while in the right panels, the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve is presented. Further, Table 2 tabulates the classification results of the multiclass classification problem, with respect to each class (see Table S1–S4), while in Table 3 the binary classification results are reported. It is evident that our models provide highly accurate results in all scenarios. Considering the multiclass scenario, the high values that exist in the diagonal of the confusion matrices showcase the ability of our models to efficiently discriminate between the different drug types. This is also supported by the accuracy scores reported in Table 2. It is apparent that both our models achieve accuracy scores exceeding 90% for all classes. Considering the binary classification problem (drug vs. control), our models yielded an AUC average score of 0.91, with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 0.85 to 0.97. Further, as Table 3 suggests, our best-performing model achieves accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and F1-score of 0.93, 0.98, 0.80, and 0.95, respectively. These results underscore both the high quality of the collected data and the efficacy of the proposed ML/DL pipeline. Moreover, our results demonstrate that the “knowledge” acquired by the model during the process of predicting Young’s modulus can be transferred to other tasks as well. In addition to automating elasticity prediction, regressing Young’s modulus enables the model to learn fine-grained representations from AFM curves, making it a strong method for model pre-training.

Visualization of the feature maps extracted by the developed CNNs. (a) Side-by-side comparison between an original image that served as input to the CNN (left panel) and a heatmap generated using the Grad-CAM algorithm (right panel). (b) Visualization of the feature maps obtained from the last convolutional layer of the CNN models using the t-SNE method, for both the binary (left panel) and the multiclass (right panel) scenarios.

Figure 5a illustrates the results of the Grad-CAM technique that is used to identify the parts of an input image that most impact the classification score. The left panel displays an instance of an image that served as input to the CNN, while the right panel demonstrates the result of applying the Grad-CAM technique to the CNN. This fused image integrates information from both the activation and convolution layers and highlights the regions of interest within the input image that have contributed significantly to CNN’s decision-making process. It is evident from the figure that the model managed to efficiently capture the shape of the AFM curve. More specifically, the valley at the bottom right and the peak at the top right of the AFM curve play a particularly significant role in the decision process of the model. Furthermore, to enhance the emphasis on the classification results, we utilized an unsupervised visualization technique known as t-SNE. In Fig. 5b, we present the outcomes of t-SNE for both binary (left panel) and multiclass (right panel) classification scenarios. It is evident that even when reducing the feature map’s dimensionality to two through unsupervised manifold learning, a remarkable level of discrimination between the different classes is achieved. This finding justifies the highly accurate results obtained by our classifiers.

Conclusions

We have developed a platform to simplify atomic force microscopy of live cells suspended in a liquid medium. The devices and methods presented herein offer a reproducible approach to the high-resolution measurement of cellular elasticity where it may serve as a metric for the efficacy of drugs or as a diagnostic marker for disease. The approach relies on a custom-designed silicone robust microwell array to gravitationally trap cells and allow their mapping via AFM compression. We validate our platform on suspended cells using three different drugs known to affect the cytoskeleton, hence altering the Young’s modulus of the cell cortex. This design can be modified to target cells of specific average diameter, and paired with an automation algorithm could potentially be applied to increase throughput and collection of AFM data that is historically time intensive, requiring a skilled operator and significant trial and error. Furthermore, the addition of a ML data analysis method allows direct automated analysis of the as-measured AFM curves, removing the need for the significant curve fitting and data modeling involved in extracting accurate Young’s modulus from AFM raw data results. Our customized ML approach not only streamlines cellular elasticity extraction by automating steps such as force curve fitting and data preprocessing but also achieves classification accuracy exceeding 0.9 for each drug condition, even for subtle differences in Young’s modulus. This significantly reduces data processing time and demonstrates that the knowledge gained by the model during Young’s modulus prediction can be effectively transferred to other tasks. Thus, predicting Young’s modulus values can serve as a valuable pertaining task for deep learning models, enabling their application to a variety of related challenges.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files. Raw data files can be provided upon request to anna.pappa@ku.ac.ae.

References

Li, M., Xi, N., Wang, Y. & Liu, L. Advances in atomic force microscopy for single-cell analysis. Nano Res. 12, 703–718 (2019).

Li, M., Dang, D., Liu, L., Xi, N. & Wang, Y. Atomic force microscopy in characterizing cell mechanics for biomedical applications: A review. IEEE Trans. Nanobiosci. 16, 523–540 (2017).

Li, M., Liu, L., Xiao, X., Xi, N. & Wang, Y. Viscoelastic properties measurement of human lymphocytes by atomic force microscopy based on magnetic beads cell isolation. IEEE Trans. Nanobiosci. 15, 398–411 (2016).

Hecht, F. M. et al. Imaging viscoelastic properties of live cells by afm: Power-law rheology on the nanoscale. Soft Matter 11, 4584–4591 (2015).

Viljoen, A. et al. Force spectroscopy of single cells using atomic force microscopy. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 1, 63 (2021).

Krieg, M. et al. Atomic force microscopy-based mechanobiology. Nat. Rev. Phys. 1, 41–57 (2019).

Lekka, M. & Pabijan, J. Measuring elastic properties of single cancer cells by afm. Atomic Force Microscopy: Methods and Protocols 315–324 (2019).

Jötten, A. M., Neidinger, S. V., Tietze, J. K., Welzel, J. & Westerhausen, C. Dynamic effective elasticity of melanoma cells under shear and elongational flow confirms estimation from force spectroscopy. Biophysica 1, 445–457 (2021).

Wu, P.-H. et al. A comparison of methods to assess cell mechanical properties. Nat. Methods 15, 491–498 (2018).

Cross, S. E., Jin, Y.-S., Rao, J. & Gimzewski, J. K. Nanomechanical analysis of cells from cancer patients. In Nano-Enabled Medical Applications 547–566 (Jenny Stanford Publishing, 2020).

Baker, E. L., Lu, J., Yu, D., Bonnecaze, R. T. & Zaman, M. H. Cancer cell stiffness: Integrated roles of three-dimensional matrix stiffness and transforming potential. Biophys. J. 99, 2048–2057 (2010).

Guck, J. et al. Optical deformability as an inherent cell marker for testing malignant transformation and metastatic competence. Biophys. J. 88, 3689–3698 (2005).

Otto, O. et al. Real-time deformability cytometry: On-the-fly cell mechanical phenotyping. Nat. Methods 12, 199–202 (2015).

Toepfner, N. et al. Detection of human disease conditions by single-cell morpho-rheological phenotyping of blood. eLife 7, e29213 (2018).

Cartagena-Rivera, A. X., Logue, J. S., Waterman, C. M. & Chadwick, R. S. Actomyosin cortical mechanical properties in nonadherent cells determined by atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J. 110, 2528–2539 (2016).

Kelkar, M., Bohec, P. & Charras, G. Mechanics of the cellular actin cortex: From signalling to shape change. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 66, 69–78 (2020).

Gavara, N. A beginner’s guide to atomic force microscopy probing for cell mechanics. Microsc. Res. Tech. 80, 75–84 (2017).

Levayer, R. & Lecuit, T. Biomechanical regulation of contractility: Spatial control and dynamics. Trends Cell Biol. 22, 61–81 (2012).

Maddox, A. S. & Burridge, K. Rhoa is required for cortical retraction and rigidity during mitotic cell rounding. J. Cell Biol. 160, 255–265 (2003).

Maître, J.-L. et al. Asymmetric division of contractile domains couples cell positioning and fate specification. Nature 536, 344–348 (2016).

Matzke, R., Jacobson, K. & Radmacher, M. Direct, high-resolution measurement of furrow stiffening during division of adherent cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 607–610 (2001).

Clark, A. G., Wartlick, O., Salbreux, G. & Paluch, E. K. Stresses at the cell surface during animal cell morphogenesis. Curr. Biol. 24, R484–R494 (2014).

Salbreux, G., Charras, G. & Paluch, E. Actin cortex mechanics and cellular morphogenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 22, 536–545 (2012).

Garcia, R. Nanomechanical mapping of soft materials with the atomic force microscope: Methods, theory and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 5850–5884 (2020).

Müller, D. J. et al. Atomic force microscopy-based force spectroscopy and multiparametric imaging of biomolecular and cellular systems. Chem. Rev. 121, 11701–11725 (2020).

Dufrêne, Y. F. et al. Imaging modes of atomic force microscopy for application in molecular and cell biology. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 295–307 (2017).

Ozkan, A. D. et al. Probe microscopy methods and applications in imaging of biological materials. In Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology Vol. 73, 153–164 (Elsevier, 2018).

Dufrêne, Y. F., Martínez-Martín, D., Medalsy, I., Alsteens, D. & Müller, D. J. Multiparametric imaging of biological systems by force-distance curve-based afm. Nat. Methods 10, 847–854 (2013).

Rosenbluth, M. J., Lam, W. A. & Fletcher, D. A. Force microscopy of nonadherent cells: A comparison of leukemia cell deformability. Biophys. J. 90, 2994–3003 (2006).

Seifert, J., Rheinlaender, J., Novak, P., Korchev, Y. E. & Schäffer, T. E. Comparison of atomic force microscopy and scanning ion conductance microscopy for live cell imaging. Langmuir 31, 6807–6813 (2015).

Weber, A., Vivanco, M. D. & Toca-Herrera, J. L. Application of self-organizing maps to afm-based viscoelastic characterization of breast cancer cell mechanics. Sci. Rep. 13, 3087 (2023).

Zhu, X. et al. Atomic force microscopy-based assessment of multimechanical cellular properties for classification of graded bladder cancer cells and cancer early diagnosis using machine learning analysis. Acta Biomater. 158, 358–373 (2023).

Sokolov, I. et al. Noninvasive diagnostic imaging using machine-learning analysis of nanoresolution images of cell surfaces: Detection of bladder cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 12920–12925 (2018).

Minelli, E. et al. A fully-automated neural network analysis of afm force-distance curves for cancer tissue diagnosis. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 143701 (2017).

Prasad, S. et al. Atomic force microscopy detects the difference in cancer cells of different neoplastic aggressiveness via machine learning. Adv. NanoBiomed Res. 3, 2300034 (2023).

Azuri, I., Rosenhek-Goldian, I., Regev-Rudzki, N., Fantner, G. & Cohen, S. R. The role of convolutional neural networks in scanning probe microscopy: A review. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 12, 878–901 (2021).

Gu, J. et al. Recent advances in convolutional neural networks. Pattern Recognit. 77, 354–377 (2018).

Li, Z., Liu, F., Yang, W., Peng, S. & Zhou, J. A survey of convolutional neural networks: Analysis, applications, and prospects. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 33, 6999–7019 (2021).

Hallfors, N. G. et al. Electrodeformation of white blood cells enriched with gold nanoparticles. Processes 10, 134 (2022).

Hallfors, N. et al. Multi-compartment lymph-node-on-a-chip enables measurement of immune cell motility in response to drugs. Bioengineering 8, 19 (2021).

Abadi, M. et al. \(\{\)TensorFlow\(\}\): a system for \(\{\)Large-Scale\(\}\) machine learning. In 12th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 16) 265–283 (2016).

GitHub–keras-team/keras: Deep Learning for humans—github.com. https://github.com/fchollet/keras. [Accessed 16-10-2024].

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Akiba, T., Sano, S., Yanase, T., Ohta, T. & Koyama, M. Optuna: A next-generation hyperparameter optimization framework. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining 2623–2631 (2019).

Cortes, C. Support-vector networks. Machine Learning (1995).

Ho, T. K. Random decision forests. In Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition Vol. 1, 278–282 (IEEE, 1995).

Cawley, G. C. & Talbot, N. L. On over-fitting in model selection and subsequent selection bias in performance evaluation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 11, 2079–2107 (2010).

Hosseini, M. et al. I tried a bunch of things: The dangers of unexpected overfitting in classification of brain data. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 119, 456–467 (2020).

Selvaraju, R. R. et al. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 618–626 (2017).

Ahrberg, C. D., Lee, J. M. & Chung, B. G. Microwell array-based digital pcr for influenza virus detection. BioChip J. 13, 269–276 (2019).

Nam, H. J., Kim, J.-H., Jung, D.-Y., Park, J. B. & Lee, H. S. Two-dimensional nanopatterning by pdms relief structures of polymeric colloidal crystals. Appl. Surf. Sci. 254, 5134–5140 (2008).

Moeller, H.-C., Mian, M. K., Shrivastava, S., Chung, B. G. & Khademhosseini, A. A microwell array system for stem cell culture. Biomaterials 29, 752–763 (2008).

Kräter, M. et al. Alterations in cell mechanics by actin cytoskeletal changes correlate with strain-specific rubella virus phenotypes for cell migration and induction of apoptosis. Cells 7, 136 (2018).

Menachery, A. et al. Dielectrophoretic characterization of dendritic cell deformability upon maturation. Biotechniques 70, 29–36 (2021).

Hernandez, P. A., Jacobsen, T. D. & Chahine, N. O. Actomyosin contractility confers mechanoprotection against tnf\(\alpha\)-induced disruption of the intervertebral disc. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba2368 (2020).

Laplaud, V. et al. Pinching the cortex of live cells reveals thickness instabilities caused by myosin ii motors. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe3640 (2021).

Zemła, J. et al. Atomic force microscopy as a tool for assessing the cellular elasticity and adhesiveness to identify cancer cells and tissues. In Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology Vol. 73, 115–124 (Elsevier, 2018).

Massey, A. et al. Mechanical properties of human tumour tissues and their implications for cancer development. Nat. Rev. Phys. 6, 269–282 (2024).

Acknowledgements

AMP, JA, and JT acknowledge funding from NIH-Al Jalila collaborative grant (AJF-NIH-19-KU). AMP and SA acknowledge funding from FSU-2022-009 grant and the Center for Catalysis and Separations (CeCaS) (grant no. RC2-2018-024), Khalifa University. AMP and VC acknowledge funding from ESIG-2023-006 from Khalifa University Sponsored Research. LH acknowledges funding from CIRA-2020-031 grant from Khalifa University. AMP, NH, VC, LH acknowledge funding from the Healthcare Engineering Innovation Center (grant number RC2-2018- 022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.H., S.L., and J.S. conceptualized and conducted the experiments and the analysis, and wrote the initial draft. S.A.A. and C.L. performed the analysis and wrote the initial draft. C.A. performed the AFM measurements. J.A. performed a stability test. V.C., C.S., and J.T. supervised the data analysis part and wrote the manuscript. A.M.P. and L.H. conceptualized and supervised the whole study, provided financial support, and wrote the final manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The corresponding author does not declare any competing interests on behalf of all authors of the paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hallfors, N., Lamprou, C., Luo, S. et al. Data-driven analysis for the evaluation of cortical mechanics of non-adherent cells. Sci Rep 15, 9700 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94315-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94315-4