Abstract

The use of nanoparticles has emerged as a popular amendment and promising approach to enhance plant resilience to environmental stressors, including salinity. Salinity stress is a critical issue in global agriculture, requiring strategies such as salt-tolerant crop varieties, soil amendments, and nanotechnology-based solutions to mitigate its effects. Therefore, this paper explores the role of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles (nTiO2) in mitigating the effects of salinity stress on soybean phenotypic variation, water content, non-enzymatic antioxidants, malondialdehyde (MDA) and mineral contents. Both 0 and 30 ppm nTiO2 treatments were applied to the soybean plants, along with six salt concentrations (0, 25, 50, 100, 150, and 200 mM NaCl) and the combined effect of nTiO2 and salinity. Salinity decreased water content, chlorophyll and carotenoids which results in a significant decrement in the total fresh and dry weights. Treatment of control and NaCl treated plants by nTiO2 showed improvements in the vegetative growth of soybean plants by increasing its chlorophyll, water content and carbohydrates. Additionally, nTiO2 application boosted the accumulation of non-enzymatic antioxidants, contributing to reduced oxidative damage (less MDA). Notably, it also mitigated Na+ accumulation while promoting K+ and Mg++ uptake in both leaves and roots, essential for maintaining ion homeostasis and metabolic function. These results suggest that nTiO2 has the potential to improve salinity tolerance in soybean by maintaining proper ion balance and reducing MDA level, offering a promising strategy for crop management in saline-prone areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nanobiotechnology is an effective innovation that deals with materials that are nanometres in size in a variety of scientific domains. These materials are widely used in many parts of agriculture, including plant nourishment, plant protection and as nano pesticides1,2. Due to the growing need for nontoxic chemicals, antiviral, antibacterial, diagnostic, anticancer, targeted drug delivery, environmentally friendly solvents, and renewable resources, biosynthesis of nanoparticles (NPs) has received a lot of attention in recent years3,4. The green synthesis method is environmentally benign because it uses bacteria, fungi, and plant extracts (leaves, flowers, seeds, and peels) to create NPs rather than a lot of chemicals5. Among the various types of NPs, titanium dioxide nanoparticles (nTiO2) have variety of uses due to their special qualities, which set them apart from many other NPs. These qualities include their tiny size, large surface area, non-toxicity, biocompatibility and their stability to various environmental circumstances. They also support agricultural plant growth, increase yield, and are utilized in food and cosmetics6. The nTiO2 have effects on plants, ranging from negative to neutral to favorable. Most importantly, when the appropriate concentrations are chosen, these NPs are used in ameliorating the harmful effects of plants under different stress conditions. It claimed that plants might better withstand a variety of environmental challenges when exposed to nTiO2, since it modulates a number of physio-biochemical mechanisms7.

One of these environmental challenges that face crops globally, leading to yearly crop losses, is salinity. Salinity stress, one significant environmental element, poses challenges to plant growth and development. Saline soils are brought about by a high accumulation of soluble salt particles of sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl−) being the most harmful stress to plants8. High salt concentrations in the soil make it harder for the roots to absorb water, which causes water shortages in the plant tissues. By raising the levels of Na+ and Cl− in plant cells, salinity stress alters a variety of plant morphological, physiological, epigenetic, and genetic traits. As a result, plants may encounter stunted growth, reduction in biomass accumulation and reduced development9. Different effects are being imposed by soil salinity such as ion toxicity, lack of necessary elements (N, P, K, Ca, Fe, Zn), osmotic stress etc. and delays the water uptake of plants from soil10. Stress brought on by salinity causes an excess of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which damage cellular membranes and components oxidatively and, in extreme saline situations, kill cells and plants. Through the antioxidant defense mechanism, plants prevent oxidative damage caused by salt by removing ROS and controlling their formation.

Plants can partially mitigate salinity disorder and restore the cell to its initial form through a variety of processes; nevertheless, if the salt dosage is excessive, the plants might not be able to respond appropriately and may perish from salt stress. The application of NPs has gained popularity recently as a way to reduce salinity stress and has recorded very brilliant results9,11. When NPs are applied as a foliar spray or seed priming agent, they activate germination enzymes, maintain ROS homeostasis, promote the synthesis of suitable solutes, and stimulate antioxidant defense systems, all of which improve crop quality and production12. One advantage of foliar application is that it uses fewer NPs, which results in less soil contamination and makes it more sustainable. The beneficial effects of nanotechnology on plants under salinity stress have been validated by several researchers13,14. Most convincingly, Mustafa et al.,15 demonstrated that the exogenous application of green nTiO2 increased the germination, physiochemical, and yield indices of wheat plants under salinity stress. Also, nTiO2 application enhanced the biochemical attributes: free amino acids, soluble sugar content, proline (Pro) content, and antioxidants of plants under different salinity levels16.

One of the principal crops affected by different abiotic stresses is soybean (Glycine max L.) which is one of the main oil crops that has several applications and is becoming more and more appreciated globally. It is an economically significant crop and a vital source of protein and oil worldwide17. Due to their recognized partial sensitivity to salt, a salt-sensitive legume, soybeans can lose up to 40% of their production, depending on the salinity level. Excessive salt in the soybean growing medium has a detrimental effect on the nodulation process, growth, and seed quality and quantity18. Salt stress negatively impacts a number of metabolic pathways, including protein synthesis, cytosolic and mitochondrial responses, assimilate translocation, water and nutrient intake and transportation, and many more19. Given the benefits of green synthesized nTiO2, including its sustainable benefits, improved bioactivity, reduced toxicity, and environmentally friendly production, this study aimed to better understand how green synthesized nTiO2 contributes to the increased resilience of soybean plants to salt stress, providing a new and ecologically friendly method of improving soybean plants.

Materials and methods

Preparation of nTiO2

For preparation of Aloe vera extract, fresh and healthy leaves were gathered and cleaned with tap water and then distilled water to get rid of any contaminants or dirt. After adding 250 g of the leaves to 1000 mL of distilled water, the mixture was heated for two hours at 90 °C. Whatman No. 1 filter paper was used to filter the extract once it had cooled. After filtering, the extract was kept for further research at -4 °C.

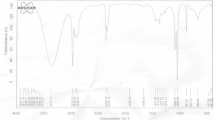

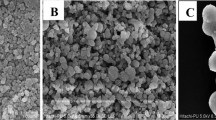

The nTiO2 were prepared using A. vera leaves extract and titanium tetrachloride as a precursor using the approach of Hanafy et al.,20 as shown in Fig. 1. The biosynthesized NPs were characterized using several techniques and recently published by Abdalla et al.,21. A suspension of 30 ppm of nTiO2 was done using deionized water for further application in soybean plants. This suspension was sonicated in a bath sonicator (Branson’s Model B200 ultrasonic) for 4 h.

Soil, plant culture, treatments and sampling

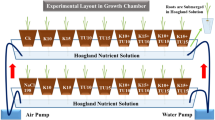

Soil was collected from Sharqia Governorate and the main chemical and physical characteristics were ascertained in a 1:5 w/v soil-water extract22,23. The soil had a clay texture, a pH of 7.64, and an electric conductivity of 1.15 dS/m, saturation percent of 54.57%, anions content of SO4 − 2 = 3.18, Cl− = 2.1, (HCO3)− = 0.37, (CO3)− = 0.05 meq/100 g soil and cations content of Na = 0.8, K = 0.35, Mg = 1.45, and Ca = 2.19 meq/100 g soil. Pot experiment with soybean (Glycine max L. Giza 35) was carried out in the greenhouse of the Botany and Microbiology Department, Faculty of Science, Zagazig University. About 2 kg of soil was taken in plastic pot of 24 cm diameter and irrigated with tap water. In the following day, 10 seeds were sown in each pot. The plants were cultivated in a greenhouse with a 12-hour light/dark cycle (light period at 25 ± 2ºC, dark period at 20 ± 2ºC). Young seedlings were only irrigated with fresh water during the first few weeks of the plantation. To reach the proper density, five plants were then maintained in every pot.

The experiment was done using six different concentrations of NaCl (0, 25, 50, 100, 150 and 200 mM) and two nTiO2 concentrations (0 and 30 ppm) with a total 12 treatments, and each treatment was 3 replicas (36 pots). The pots were arranged randomly within the greenhouse to avoid positional bias and irrigation volume was standardized across all treatments to maintain uniform soil moisture levels. After two weeks from sowing, NaCl solutions were added gradually and irrigations were performed at sunset, two times a week by different salt concentrations. In a regular with salt irrigation, a constant volume (5 ml/plant) of nTiO2 at 30 ppm concentration was sprayed twice a week by a hand pump sprayer. Non treated plants were used as control irrigated and sprayed with water.

At intervals of 2 weeks, both control and treated plant samples were collected at fixed time in 2 periods (15 and 30 days after treatment with salt). The experimental overview was shown in Fig. 2a. Part of these samples is used for measuring phenotypic variations, leaf water content and pigment fractions; another part was frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -20oC for biochemical analysis (lipid peroxidation and non-enzymatic antioxidants). As well, some samples were dried in an electrical oven for 3 days at 60oC for measuring the dry weight (dwt), carbohydrates and the elemental analysis (Na+, K+ and Mg++).

Measurement of phenotypic variations, leaf water content and pigment fractions

Total fresh weight (Tfwt, g) and total dry weight (Tdwt, g) of soybean were measured and number of leaves was counted after 15 and 30 days from salt application. To test the aforementioned characteristics, three plants were randomly selected from each treatment.

The method outlined by Barr and Weatherley24 was used to measure the water content (WC), relative water content (RWC), and water saturation deficit (WSD). After cutting the leaf into 5–10 cm2, it was immediately weighed to determine its fwt. The leaf sample was left in a Petri dish with deionized water for four hours at room temperature. The sample was removed from the water after four hours, and the surface water was then collected and weighed one more to determine the completely turgid weight (twt). The sample was dried for 24 h at 60 °C in an oven before being weighed once more (dwt). The following formulas were utilized to determine WC, RWC, and WSD:

The Metzner et al.25 method was used to determine the pigment content. Using pre-washed sand and 5 mL of an 85% cold aqueous acetone solution, fresh soybean leaves (0.125 g) were pulverised in a mortar. After centrifuging the homogenate, the supernatant was diluted with 85% acetone to a predetermined volume (10 mL). Using a spectrophotometer, the optical density was stated at 663, 644, and 452.5 nm in relation to a blank of 85% acetone. The pigment content of the samples was determined using the following formulas and expressed in µg/mL.

Note: A = Light absorption in wavelengths 663, 644 and 452.5 nm.

Following calculation, the pigment concentration was reported as mg/g fwt.

Determination of the total soluble carbohydrates content and lipid peroxidation

According to Dubois et al.,26, the phenol sulphuric acid method was used to measure carbohydrates. Following calculation, the total soluble carbohydrate content was represented as mg/g dwt in the manner described below:

Malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration, which was calculated by homogenizing known tissue weight with 5 mL of 5% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid and centrifuging at 8000 rpm for 10 min, was used to measure the degree of lipid peroxidation27. Then, 0.4 mL of the supernatant was mixed with 0.4 mL of 5% trichloroacetic acid that contained 0.67% (w/v) thiobarbituric acid (TBA). Using a spectrophotometer, the absorbance was measured at 532 and 600 nm. An extinction coefficient of 155 mM− 1 cm− 1 was used to quantify MDA, and the result was represented as nmol/g fwt using the subsequent formula:

where \(\varepsilon\) is the specific extinction coefficient (= 155 mM− 1 cm− 1), V is the volume of the extract, wt is the weight of the leaf, A is the absorbance.

Determination of non-enzymatic antioxidants (proline; pro, total phenolic content; TPC and total flavonoid content; TFC)

Pro content was calculated using the Bates et al.,28 method. In 10 mL of 3% aqueous sulphosalicylic acid, 0.5 g of soybean tissue were homogenized. Two mL of glacial acetic acid and two mL of acid ninhydrin were combined with two ml of the filtrate in a glass test tube, which was then heated for one hour in a boiling water bath. The tubes were submerged in an ice bath to halt the reaction. After adding four mL of toluene to the reaction mixture, it was well agitated for 15–20 s. Then, organic and inorganic phases are separated, obtaining the chromophore dissolved in toluene. At 520 nm, a spectrophotometer was used to quantify the optical density of the generated color. The formula for expressing Pro as µg/g fwt was as follows:

Note: − 115.5 is the molecular weight of Pro.

After 95% ethanol extraction, 1 mL of the extract was combined with 1 mL of Folin reagent and 1 mL of 20% Na2CO3 to determine the TPC in soybean leaf tissues quantitatively29. At 650 nm, the absorbance was measured with a spectrophotometer. The TPC was tested using gallic acid as a reference, and the results were reported as mg/g fwt of gallic acid equivalent (GAE).

Following Zou et al.,30 technique, TFC was evaluated in soybean plant leaves using the aluminium chloride colorimetric test following extraction with 95% ethanol. Four mL of distilled water were mixed with a 100 µL aliquot of alcoholic extract. 0.3 mL of 5% sodium nitrite was added at zero time. 0.3 mL of 10% aluminium chloride was added after 5 min. Two mL of 1 M sodium hydroxide were added to the liquid after six minutes. A spectrophotometer was used to detect absorbance at 510 nm in comparison to a blank. The quercetin standard curve was used to determine TFC, which was then represented as mg/g fwt of quercetin equivalent (QE).

Elemental analysis of sodium (Na+), potassium (K+) and magnesium (Mg++) in soybean shoot and roots

The soybean samples (shoot and root; 0.5 g), after being oven dried at 60 °C, were crushed. Then, they were incinerated in a muffle furnace (Thermolyne 48000 model) at high temperature (525–600 °C) for 3 h. Ash of plant samples were dissolved in 10 mL of 2% HNO3 and kept in an incubator overnight at 50 °C. After that, the solutions were filtered and reached total volume (25 mL) by deionized water following the method of Ward and Johnston31. Na+, K+ and Mg++ were determined spectrophotometrically using atomic absorption spectrophotometer (AAS; Buck scientific 210VGP) at the Central Laboratory, Faculty of Veterinary medicine, Zagazig University. Na+, K+ and Mg++ were computed using the subsequent formula:

where R is the element concentration reading in parts per million (ppm) from the AAS digital scale, D is the prepared sample’s dilution, and dwt is the sample’s dry weight.

Data and statistical evaluation

The impact of nTiO2 and salinity stress on growth, biochemical components, and minerals was determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Following post hoc analysis, means were compared using Duncan’s multiple comparison tests (p ≤ 0.05) with the SPSS statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Excel was used to plot the figures. Past was used to evaluate the principal component analysis (PCA) and Pearson’s correlation matrix.

Results

Impact of nTiO2 on phenotypic variations, leaf water content and chlorophylls of soybean plants exposed to salinity

Data for phenotypic variation e.g. Tfwt, Tdwt and leaves number of soybean are listed in Fig. 2b, c; Table 1. Analysis of variance for all of these characteristics revealed that the treatments (control, salt, nTiO2, and their interaction) differed significantly (p ≤ 0.05). Salt stress had a major impact on plant growth, but applying nTiO2 greatly enhanced it. We found that applying salt solutions significantly decreased these metrics; for example, applying a 50 mM salt solution reduced the soybean’s Tfwt (3.78 g ± 0.10 cd), and Tdwt (0.574 g ± 0.011e) in comparison to the corresponding controls. A salt solution at a higher concentration (150 mM) produced an inhibitory effect and reduced the Tfwt (2.7 g ± 0.071 h) and Tdwt (0.5 g ± 0.006 h) respectively, in contrast to the respective controls. However, noteworthy findings emerged in the nTiO2 sprayed plants where nTiO2 mostly improved total fresh and dry matter in the salt stressed plants (Fig. 2c). Applying nTiO2 alone to the plants, 30 ppm, increased the Tfwt (19.5%) and Tdwt (24.2%), compared to their respective controls. Under 50 mM salt solution, when 30 ppm of plant-based nTiO2 was applied, the Tfwt and Tdwt of the plants increased noticeably (24.8 and 21.9%) compared to plants grown under salt only. Similarly, these nTiO2 enhanced the Tfwt (14.8%) and Tdwt (20%), at 150 mM of salt solution in contrast to plants that are grown under stress only.

Water status (WC, RWC and WSD) of nTiO2 sprayed and non-sprayed soybean plants were greatly impacted when salt stress was applied as shown in Table 2. Regarding RWC, results showed that soybean plants sprayed with nTiO2 possess the highest RWC when not under salt stress condition (60.04%) after 30 days of salt application. RWC of soybean plants exposed to 100 and 150 mM NaCl decreased by 14.011 and 19.88% compared to control ones grown under non-salt stress condition after 30 days. RWC and WC in nTiO2 and non-sprayed plants were markedly lessened with increasing salt stress. Moreover, soybean plants sprayed with nTiO2 had significantly higher values than non sprayed ones regardless of salt treatments.

One of the most significant elements that impact a plant’s ability to grow and develop is the level of chlorophyll in it. The effects of salinity, nTiO2 and their interactions on the recorded photosynthetic pigments (chlorophylls a, b and carotenoids) of the soybean plant leaves grown throughout the growth period are presented in Table 3. Data showed that chlorophylls and carotenoids in the leaves were decreased significantly under salt stress, whereas the foliar application of nTiO2 showed a less decrease where, the interaction treatments showed that nTiO2 lessened the harmful effect of salinity throughout the experimental period.

Variations of carbohydrate content and lipid peroxidation as a result of N TiO2 application in soybean plants exposed to salinity

Figure 3a showed the effect of different NaCl concentrations, nTiO2 application and their interaction on total soluble carbohydrates content. In this investigation, increasing salt concentrations led to a rise in the production of carbohydrates in soybean plants. Also, the exogenous application of nTiO2 significantly caused further increase of carbohydrates content under salt stress. It was apparent that salinity stress increased lipid peroxidation of membranes and subsequently increased MDA content of soybean plant leaves. With increasing salt concentrations, there was a subsequent increase in MDA content, recording higher MDA values at higher salt concentration after 30 days of application. In nTiO2 sprayed soybean plants, MDA content was significantly decreased under control and salt stressed conditions compared to salt stressed plants only. Furthermore, results in Fig. 3b revealed that the increasing in MDA content was reached to 260.32 and 417.08% at 100 and 150 mM NaCl, respectively in non-nTiO2 plants after 30 days while with nTiO2 application, these percentages were decreased (142.17 and 274.19) in comparison with plants grown under the control condition. Of particular note, the inhibitory effect of salinity on lipid peroxidation of soybean plants was somewhat lessened by using nTiO2.

Total soluble carbohydrates (mg/g dwt) and malondialdehyde content (MDA; nmol/g fwt) of soybean plants grown under different NaCl concentrations and sprayed with or without nTiO2 after 15 days (a,c) and 30 days (b,d) of salt application. *Data represent means ± standard errors (error bars) of three biological replicates. Different letters above columns indicate significant difference (p < 0·05), according to a Duncan multiple range test.

Variations in non-enzymatic antioxidants (Pro, TPC and TFC)

Results in Fig. 4a, b demonstrated that, in comparison to the control, salt stress caused a noticeable rise in the Pro content in the leaves of both nTiO2 and non-nTiO2 sprayed soybean plants, where the maximum level was seen at 150 and 200 mM NaCl. Furthermore, Pro content in leaves of nTiO2 applied soybean plants was higher than that in non-nTiO2 applied plants grown under control or salt stressed condition. Where the Pro content in non-nTiO2 soybean plant leaves grown at 50 mM NaCl were 20.49 and 20.87 µg/g fwt, while with nTiO2 application, this value was increased (22.67 and 23.74 µg/g fwt) after 15 and 30 days, respectively.

Proline content (Pro; µg/g fwt), total flavonoid content (TFC; mg QE/g fwt) and total phenolic content (TPC; mg GAE/g fwt) of soybean plants grown under different NaCl concentrations and sprayed with or without nTiO2 after 15 days (a,c,e) and 30 days (b,d,f) of salt application. Data represent means ± standard errors (error bars) of three biological replicates. Different letters above columns indicate significant difference (p < 0·05), according to a Duncan multiple range test.

The production of secondary metabolites, including flavonoids and phenolic compounds, is increased under salinity stress (Fig. 4b-e). To determine whether a non-enzymatic mechanism driving nTiO2’ induction of salt tolerance in soybean plants, TPC and TFC were detected after 15 days and 30 days (Fig. 4b-e). As shown in this figure, the TPC and TFC of soybean plants were measured as 2.46 mg GAE/g fwt and 0.52 mg QE/ g fwt in the control. As well, noticeable and gradual increases in their contents were noticed with increasing NaCl concentrations. The TPC increased by 52.37% and 71.88% in plants challenged with 50 and 100 mM NaCl, respectively; these percentages were increased by 67.31% and 96.44% with green produced nTiO2 treatment compared to control in untreated plants only after 30 days.

Changes of Na+ K+, and Mg++ in shoots and roots of soybean

Application of nTiO2, salt stress and their interactions significantly affected nutrients content of soybean plants. The present study showed that salt stress caused a notable rise in Na+ and a reduction in K+ and Mg++ buildup in leaves and roots of soybean as shown in Tables 4 and 5. However, interestingly, nTiO2 treated plant exhibited reduced Na+ accumulation and enhanced K+ and Mg++ under NaCl stress. It has been noted that the salt stress led to low K+/Na+ ratio (high Na+/K+), while nTiO2 application raised this ratio (K+/Na+).

Principal component analysis and correlation matrix among phenotypic, biochemical parameters and minerals

Principal component analysis (PCA) shows the association among the phenotypic, physio-biochemical parameters and minerals of soybean plants exposed to the 12 treatments (Fig. 5a). The first principal component (PC1) accounted for 59.4% of the variance in the obtained data, whereas the second component (PC2) captured 38.8% of the variance under the different treatments explained a total of 98.2% overall data variability. The biplot of various parameters indicated that plant height, WC, RWC, and Tfwt were positively correlated with each other and negatively with MDA content. Also, this biplot (Fig. 5a) authenticated the grouping of 12 treatments used in this study. The nTiO2 was adjudged as the best treatment and its effect was followed by that of control treatment. Both these treatments were clustered on the upper left-hand rectangles of the plot. The NaCl (50, 100, 150 and 200 mM) treatments posed negative impacts on soybean plants, and this was confirmed by the plot. On the PCA-linked biplot, the most obvious result is that all the salinity treatments were highly associated with WSD and MDA. According to the correlation matrix (Fig. 5b), WSD, MDA, Na content in shoot and roots were negatively correlated with all growth parameters and pigment fractions. Also, this correlation revealed a strong positive correlation between different growth parameters measured (plant height, Tfwt and Tdwt) with all the pigment fractions (chlorophylls a, b and carotenoids) which indicate the role of increasing pigments (increasing photosynthesis) in enhancing growth parameters. Collectively, Fig. 6 summarized the effect of salinity and nTiO2 on soybean plants based on the different parameters measured in this study.

Multivariate analysis: (a) Principal component analysis (biplot) between the different treatments and the studied parameters of soybean plants under the effects of salinity and nTiO2. (b) Pearson’s correlation matrix of 21 traits in soybean plants. Note: The intensity of color ranges from blue (positive) to red (negative) and the size of the circles show strength of significant correlation (p ≤ 0.05).

Discussion

The nTiO2 were green synthesized using A. vera extract and their characterization showed a well-crystallized anatase profile with tetragonal structure of the particles and their sizes ranged between 10 and 25 nm as previously mentioned in our recently studies21,32. Employing NPs is seen to be a viable way to get around the challenges associated with plant growth and development under different stresses33. Assessment of the impact of nTiO2 on soybean plants and research on the related alterations in treated plants was recently done32 while further understand the mechanism of resilience is still required.

The present results indicated the inhibition of the measured growth parameters by NaCl treatments. These findings are congruent with the results of salinity effects on wheat, tomato and faba bean plants19,34,35 respectively, implying that it might be an unintended result of Na+ ions. Salinity stress affects a plant’s growth and its physiochemical properties as well36. A notable decrease in growth and biomass was brought on by salt stress because of the increased translocation of Na+ from the roots to the shoots or the lack of nutrients10. Conversely, application of nTiO2 improved the growth parameters and this agreed with Jaberzadeh et al.,37 who reported that nTiO2 enhanced the growth and yield-related characteristics of wheat plants under stress. In their 2018 study, Rafique et al.38 demonstrated that following 60 days of exposure to soil-applied nTiO2, Triticum aestivum L. plants’ root and shoot lengths and P uptake were significantly (p < 0.05) higher between 20 and 60 mg kg− 1 than the control (0 mg kg− 1 nTiO2), but then decreased at 80 and 100 mg kg− 1 in comparison to 60 mg kg− 1 nTiO2. Likewise, the research carried out by Badshah et al.,16 demonstrated that the application of nTiO2 improved plant development, which may be connected to the synthesis of antioxidant enzymes and osmotic adjustments in plants. In agriculture, nanotechnology is important and aids in crop management. The more acceptable approach is TiO2 biosynthesis since it promotes growth and has a notable impact on plant growth when exposed to salinity stress39. Applying nTiO2 enhanced the absorption of macro- and micronutrients, boosted the growth characteristics of plants (e.g., length, fresh weight, and number of leaves), and lessened the adverse effects of salinity, such as interfering with photosynthesis and essential element absorption18.

Plants cultivated under salt stress are exposed to physiological drought because Na+ and Cl− ions bind water that the plants require to mobilize40,41. The water status of jute and fenugreek plants is impacted by salt stress, which is consistent with findings by Chaudhuri and Choudhuri42 and Metwally and Abdelhameed43. The buildup of Na+ in salty soils causes a drop in osmotic potential during salinity stress, which might lower the soil’s WC44. Under conditions of salt stress, abscisic acid is generated, which closes the stomata and lowers the water absorbed by the roots and affects the transpiration process, reducing the WC in the cell45. These findings are also agreed with Özdemir et al.,46 where they found that specific physiological reactions, such as stomatal closure, increased rates of leaf senescence, and reduced plant growth, happen when plants endure salt stress. When plants are stressed by salinity, they absorb less water overall. Increased osmotic stress from high salt concentrations in soil solution restricts the plant’s ability to absorb water, which impacts leaf WC, stomatal conductance, growth (accelerating senescence and death), and photosynthesis (decrease in chlorophyll concentrations), all of which contribute to a decrease in plant growth8.

According to Mahmoud et al.,47, in many plant species, NPs can alleviate osmotic stress caused by salt by improving water status and water use efficiency. In this connection, the role of nTiO2 in enhancing the performance of soybean plant leaves which represented by WC and RWC, was greatly apparent after 30 days of salt application. Our results are consistent with the ones obtained by18, who applied nTiO2 to wheat plants impacted by salt and reported comparable results. It has also been demonstrated that nTiO2 treatment raises the RWC in stevia in addition to maintaining the cells’ water status14. Moreover, plants treated with NPs continue to exhibit increased whole-plant hydraulic conductance, leaf and root water content, stomatal conductance, and transpiration rate48. NPs have been shown to enhance root hydraulic conductance by upregulating the expression of the plasma-membrane intrinsic protein aquaporins. This may help to boost water uptake and decrease membrane damage and oxidative stress. According to a study by Elhefnawy et al.49, tomato seeds treated with NPs had a moisture content that was 19% higher than that of untreated seeds. These results implied that the NPs encourage water absorption and retention.

Regarding the content of chlorophylls and carotenoids, salt stress decreased them significantly whereas the foliar application of nTiO2 showed a less decrease. When salinity stress occurs, it influences the leaf area, the leaf area becomes short and subsequent chlorophyll decreases. Under salinity stress, numerous plant species have been shown to have decreased photosynthetic activity50,51. When under salinity stress, stomatal conductance significantly decreases, lowering CO2 concentration and net photosynthetic rate52,53. Additionally, El-Shawa et al.,54 demonstrated that salt stress resulted in a notable decline in the concentrations of chlorophyll and carotenoids in calendula plants as a result of the inhibition of PSII activity and a decrease in chlorophyll and CO2 assimilation in leaves due to the accumulation of toxic ions55.

Consistent with the present results of increasing chlorophylls and carotenoids following nTiO2 application, a research by Rafique et al.38 found that when nTiO2 were applied to T. aestivum L. plants, the amount of chlorophyll increased by 32.3% at 60 mg kg− 1 compared to the control, but decreased by 11.1% at 100 mg kg− 1. Obviously, applying nTiO2 delayed the chloroplast senescence process56 and stimulated Rubilose carboxylase activity, increasing the amount of chlorophyll and the rate of photosynthetic activity57,58. The treatments with nTiO2 regulate the activity of nitrogen metabolism-related enzymes and improve the process of turning inorganic nitrogen into organic nitrogen, together with the synthesis of chlorophyll and proteins56,59. Under salt stress, application of the majority of NPs (Ag, ZnO, TiO2, Fe, and Se) increased the amount of chlorophyll60. According to Phothi and Theerakarunwong61, these findings demonstrated the physiological role of nTiO2 in boosting light harvesting, initiating photosynthesis, and stimulating the concentration of proteins and pigments. Under salinity stress, nTiO2 increased the carotenoid content of wheat cultivars15.

In order to survive in saline environments, plants gather fundamental osmolytes such Pro, protein, and carbohydrates as a vital way to compensate for osmotic stress caused by salinity62; these osmolytes are non-toxic at elevated levels63. Our results of increasing carbohydrates in soybean plants under salt stress and nTiO2 application are in line with those of15, who applied nTiO2 to plants of T. aestivum L. under salt stress and reported comparable outcomes. The nTiO2 treatment raised Pro and carbohydrate contents in plants, which can aid soybean plants exposed to salt as osmoprotectants by stabilizing membranes and preventing enzyme denaturation64. According to numerous reports, the application of NPs can also improve plant resistance to salinity stress by altering the concentrations of solutes like total soluble sugars and amino acids (like Pro)48,65,66. This reduces the osmotic shock caused by NaCl stress because of ion toxicity (Na+ and Cl−). For instance, Farouk and Al-Amri67 found that applying Zn NPs to canola (Brassica napus L.) plants under salinity stress reduced the negative effects of salt through ionic control and osmolyte production. In a different study, Mohamed et al.,68 showed that treating seeds with Ag NPs prior to sowing enhanced the growth, Pro, and soluble sugars of wheat seedlings under salt stress. Likewise, Metwally and Abdelhameed4 and Abdelaziz et al.,69 stated that NPs application to pea and eggplant plants stimulated the total soluble carbohydrates and total soluble protein.

Carbohydrates are significant organic solutes that may play a key role in stress reduction and aid in maintaining cell homeostasis, through the action of signal molecules, carbon storage, and osmoprotectants. Carbohydrates like sugars (such as glucose, fructose, and trehalose) and starch have been shown to function as metabolite and nutrient signaling molecules and to be involved in the immune system’s response to a number of stressors70,71. Additionally, the high carbohydrate accumulation helps to prevent oxidative harms by scavenging ROS and maintaining protein structure during salt stress. Abobatta and Waleed Fouad72 stated that soluble sugars are significant osmolytes that, in glycophytes exposed to salty environments, can account for as much as 50% of the entire osmotic potential.

MDA is a measure of membrane stability or, indirectly, a marker of membrane damage caused by high ROS. The stability of the membrane is disturbed when ROS produced by NaCl interacts with membrane proteins, causing peptide chain fragmentation and proteolysis. ROS can attack the lipid molecules in the membranes, thereby rendering the membranes permeable for electrolytes to leach out. As well, ROS causes membranes’ unsaturated lipid component peroxiding, which causes the membranes to lose their integrity and so contain more MDA73. Application of NPs decreased lipid peroxidation in plants under salt stress as reported in several studies. For instance, Sheikhalipour et al.,14, Alharby et al.,19 and Abdel Latef et al.,39 confirmed that application of nTiO2 reduced the MDA levels in the saline environment. The reason might be due to increased activities of antioxidants in nTiO2 treated plants which reduce lipid peroxidation and scavenge the generation of radicals before they react with the membrane lipids74. On the contrary, numerous studies have demonstrated that plants treated with higher concentration of metal ions had higher MDA contents75,76 which attributed to the generation of high ROS and oxidative stress from metal ions produced from NPs77,78. The discrepancy in outcomes may stem from differences in NPs synthesis, concentration, plant species, and growth conditions.

It has been shown that Pro stabilizes subcellular structures (proteins and membranes), buffers cellular redox potential under stress, and acts as a free radical scavenger and carbon and nitrogen storage sink79. It helps in maintaining the water balance of plants so that the stress induced is reduced80. It also influences protein turn over and directly regulates stress protective proteins81. Our results of Pro accumulation align with those of Mustafa et al.15, who reported similar results by applying nTiO2 on T. aestivum L. plants affected by salinity stress. Pro levels in plants are accelerated by nTiO2 treatment, which can benefit soybean plants exposed to salt as osmoprotectants by stabilizing membranes and preventing enzyme denaturation64. An increase in Pro makes the cell more stress-tolerant and protects cellular structures and cytosolic enzymes.

Phenolics and flavonoids, which are created under stressful circumstances, are essential to the growth and development of plants and also have a significant nutritional component. They also go by the name of antioxidants since they are crucial in minimizing the harm brought on by oxidative stress7. The present result showed an increase in the TPC and TFC in soybean plants under salt stress. Similarly, a noticeable increase in their contents was found at 50 and 100 mM NaCl treated tomato seedlings16. Furthermore, the findings of phenolics and flavonoid increase in soybean leaves were consistent with previous research on artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) leaves by Rezazadeh et al.,82. This could be explained by the discovery that stress causes an increase in enzymes of the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway, such as chalcone synthase and phenylalanine ammonia-lyase83.

The current study demonstrated how applying nTiO2 can help reducing the negative effects of salt stress by higher accumulation of TPC and TFC. There is also evidence that these compounds have increased protective effects against salt stress, helping plants maintain ROS levels in harmful environments and promoting quick elimination to maintain a stable metabolism. These results align with Mustafa et al.,15 findings. According to earlier research by Lafmejani et al.,84, this might be the consequence of increased expression of particular biosynthetic enzymes involved in the synthesis of these components and substrate availability. It is yet unclear exactly how the application of NPs affects plant secondary metabolites. NPs may function as elicitors for secondary metabolite formation in plants by triggering several cellular signal transduction pathways (e.g., mitogen-activated protein kinases, calcium flux, and ROS metabolism), according to recent integrated phytochemical and genomic investigations. Therefore, the observed modifications in the aforementioned pathways may result in changes in the levels of gene expression and the activation of metabolic enzymes, which may influence the synthesis of secondary metabolites85.

Plants’ ability to regulate their ion homeostasis is disrupted by salt stress86. The current investigation showed that salt stress significantly increased Na+ and decreased K+ and Mg++ accumulation. These findings are consistent with those of Elhindi et al.,87, who found that salinity causes Andrographis paniculata to accumulate more Na+ and accumulate less K+ and Mg++. Because Na+ ions compete with K+ for binding sites, elevated Na+ always inhibits K+ absorption. Moreover, Ghassemi-Golezani and Abdoli88 revealed that excessive salinity stress frequently prevents rapeseed (B. napus L.) plants from absorbing and distributing vital minerals (Mg++ and K+), which are necessary for the production of chlorophyll.

However, interestingly, nTiO2 treated plant exhibited reduced Na+ accumulation and enhanced K+ and Mg++ under NaCl stress. The heightened build-up of nutrients (K+ and Mg++) with nTiO2 application under control and saline conditions improved the plant growth because they are important components of many metabolically active compounds and play a crucial role in several physiological and biological functions, also improved the plant tolerance by inducing many enzymes associated with nutrients assimilation and antioxidant enzymes. Mg++ being the component of chlorophyll helps to enhance the photosynthetic rate. NPs also improve the plant’s capacity to effectively absorb and use water and fertilizers from the soil89. According to Gohari et al.,90, nTiO2 has also been shown to hasten the accumulation of other vital elements in plant shoots, including Fe, Ca, Mn, Zn, B, and K. Mustafa et al.,15 claim that by enhancing the uptake of vital nutrients and preventing the uptake of Na+ ions, nTiO2 improves growth and yield characteristics. It works as a standard that provides a sufficient amount of vital elements to plant roots by utilizing the sequestration process of essential elements by NPs. NPs can improve the solubility and bioavailability of certain nutrients in the soil, leading to increased nutrient absorption by plant roots91. According to the findings of Alharby et al.,19, the addition of nTiO2 raised the amounts of P, K, Fe, and Mn in wheat up to 400 mg/kg. At higher doses of nTiO2 (600 mg/kg), the concentrations of these elements declined. Additionally, wheat plants showed improvement in P concentration under nTiO2 application up to 60 mg/kg, which progressively decreased as nTiO2 concentration increased up to 100 mg/kg38, which could be because root exudation mobilized the soil P, increasing plant uptake of it92. Moreover, nTiO2 might stimulate the release of organic acids from roots, leading to rhizosphere acidification. This acidification can alter nutrient availability and uptake. For instance, a study on maize seedlings treated with nTiO2 observed increased exudation of citric, lactic, and fumaric acids, accompanied by a decrease in exudate pH93. Such changes in root exudation patterns can influence the solubility and mobility of nutrients like K⁺ and Mg²⁺, facilitating their uptake. Different cultivars, plant species, experimental settings, and competition between nTiO2 and mineral elements during plant uptake could all contribute to the diversity in nutrient uptake by plants under nTiO2.

It has been noted that the high K+/Na+ ratio (low Na+/K+), which is disturbed by salinity stress, is one of the most crucial elements for plant resistance to salinity stress. NPs are known to raise this ratio (Sytar et al., 94; Tahjib-UI-Arif et al., 95), which enhances the plant’s osmotic potential and promotes better plant growth in the face of salinity stress. The current findings (Fig. 7) demonstrated how nTiO2 may help plants absorb more K+ than Na+ when they are under salt stress (low Na+/K+). Parida and Das96 previously discussed the role of K+ in plants’ adaptation to salt. They found that plants maintain low concentrations of Na+ and high concentrations of K+ in the cytosol by controlling the expression and activity of H+ pumps, which provide the driving force for transport, as well as K+ and Na+ transporters.

Na+/K+ in root and shoot of soybean plants grown under different NaCl concentrations and sprayed with or without nTiO2 after 15 days (a,c) and 30 days (b,d) of salt application. Data represent means ± standard errors (error bars) of three biological replicates. Different letters above columns indicate significant difference (p < 0·05), according to a Duncan multiple range test.

Maintaining a greater K+/Na+ ratio is thought to be a key tactic used by plants to lessen harmful alterations brought on by stress97,98. Effective removal of harmful ions, such as Na+, helps maintain tissue osmotic potential, hence minimizing hyperosmotic consequences. According to the study of Alharby et al.,19, enhanced uptake of P, K+ and Ca2+ due to nTiO2 may be as result of selective absorption of these essential ions over deleterious Na+ and hence resulting in maintaining lower Na+/K+ ratio. It appears that the role of the nTiO2 in alleviating salt stress is partially due to the prevention of Na+ absorption and translocation to shoot tissues.

Conclusions

This study emphasizes how nTiO2 can improve the performance of soybean plants in saline environments. MDA and Na+ content in both shoots and roots decreased as a result of the nTiO2’s action. Moreover, nTiO2 markedly modulated phenotypic attributes, key physiological and biochemical parameters including RWC, Pro, chlorophylls, TPC and TFC. As well, the application of nTiO2 enhanced uptake of essential element such as K+ and Mg++. These effects are involved in bolstering soybean tolerance to the toxic and osmotic stresses induced by salinity. From an applied perspective, these results suggest that nTiO2 could serve as a promising nanomaterial for improving soybean cultivation in saline soils, offering a potential strategy to enhance crop productivity in salt-affected agricultural regions. In order to clarify the fundamental mechanisms of NPs interactions in subsequent research, these findings provide the groundwork for a deeper comprehension of NPs impacts. Future studies should focus on validating these findings under field conditions and elucidating the underlying molecular mechanisms.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- nTiO2 :

-

Titanium dioxide nanoparticles

- NPs:

-

Nanoparticles

- MDA:

-

Malondialdehyde

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- Pro:

-

Proline

- TPC:

-

Total phenolic content

- TFC:

-

Total flavonoid content

- GAE:

-

Gallic acid equivalent

- QE:

-

Quercetin equivalent

- Tfwt:

-

Total fresh weight

References

Hawrylak-Nowak, B., Hasanuzzaman, M. & Matraszek-Gawron, R. Mechanisms of selenium-induced enhancement of abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Plant nutrients and abiotic stress tolerance. 269–295 (2018).

Nabi, G., Anjum, T., Aftab, Z. E. H., Rizwana, H. & Akram, W. TiO2 nanoparticles: green synthesis and their role in lessening the damage of Colletotrichum graminicola in sorghum. Food Sci. Nutr. 12, 7379–7391 (2024).

Khanna, K. et al. Green biosynthesis of nanoparticles mechanistic aspects and applications. Environ. Appl. Microb. Nanatechnol., 99–126 (2023).

Metwally, R. & Abdelhameed, R. Co-application of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and nano-ZnFe2O4 improves primary metabolites, enzymes and NPK status of pea (Pisum sativum L.) plants. J. Plant Nutr. 47, 468–486 (2024).

Jeevanandam, J. et al. Green approaches for the synthesis of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles using microbial and plant extracts. Nanoscale 14, 2534–2571 (2022).

Chandoliya, R., Sharma, S., Sharma, V., Joshi, R. & Sivanesan, I. Titanium dioxide nanoparticle: A comprehensive review on synthesis, applications and toxicity. Plants 21, 2964 (2024).

Khan, M. et al. Nitric oxide is involved in Nano-Titanium Dioxide-Induced activation of antioxidant defense system and accumulation of osmolytes under Water-Deficit stress in Vicia Faba L. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 190, 110152–110165 (2020).

Munns, R. & Tester, M. Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 59, 651–681 (2008).

Zafar, S. & Hasnain, Z. Modulations of wheat growth by selenium nanoparticles under salinity stress. BMC Plant. Biol. 24, 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-024-04720-6 (2024). Danish, S.

Sabagh, E. L. et al. Salinity stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) in the changing climate: adaptation and management strategies. Front. Agron. 3, 661932 (2021).

Khalid, M. F., Jawaid, M. Z., Nawaz, M., Shakoor, R. A. & Ahmed, T. Employing titanium dioxide nanoparticles as biostimulant against salinity: improving antioxidative defense and reactive oxygen species balancing in eggplant seedlings. Antioxidants 13, 1209 (2024).

Singh, A., Rajput, V. D. & Agrawal, S. Nanoparticles mediated salt stress resilience: A holistic exploration of physiological, biochemical, and Nano-omics approaches. Reviews Env Contam. (formerly:Residue Reviews). 262, 19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44169-024-00070-4 (2024).

Etesami, H., Fatemi, H. & Rizwan, M. Interactions of nanoparticles and salinity stress at physiological, biochemical and molecular levels in plants: A review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 225, 112769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112769 (2021).

Sheikhalipour, M. et al. Salt stress mitigation via the foliar application of Chitosan-Functionalized selenium and anatase titanium dioxide nanoparticles in stevia (Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni). Molecules 26, 4090 (2021).

Mustafa, N. et al. Exogenous application of green titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) to improve the germination, physiochemical, and yield parameters of wheat plants under salinity stress. Molecules 27, 4884 (2022).

Badshah, I. et al. Biogenic titanium dioxide nanoparticles ameliorate the effect of salinity stress in wheat crop. Agronomy 13, 352 (2023).

Soliman, E. R. S., Abdelhameed, R. E. & Metwally, R. A. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in drought-resilient soybeans (Glycine max L.): unraveling the morphological, physio-biochemical traits, and expression of polyamine biosynthesis genes. Bot. Stud. 10, (2025).

Khan, M. et al. Halotolerant rhizobacterial strains mitigate the adverse effects of NaCl stress in soybean seedlings. Biomed. Res. Int. 20199530963 2019 (2019).

Alharby, H., Hasanuzzaman, M., Al-Zahrani, H. & Hakeem, K. Exogenous selenium mitigates salt stress in soybean by improving growth, physiology, glutathione homeostasis and antioxidant defense. Phyton- Int. J. Experimental Bot. 90, 373–388 (2021).

Hanafy, M., Abdel Fadeel, D., Elywa, M. & Kelany, N. Green synthesis and characterization of TiO2 nanoparticles Using (Aloe vera) Extract at Different pH Value. Scientific Journal of King Faisal University 21, 103–10 (2020). (2020).

Abdalla, H., Adarosy, M. H., Hegazy, H. S. & Abdelhameed, R. E. Potential of green synthesized titanium dioxide nanoparticles for enhancing seedling emergence, Vigor and tolerance indices and DPPH free radical scavenging in two varieties of soybean under salinity stress. BMC Plant. Biology 22, 560. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-022-03945-7

Jackson, M. L. Soil chemical analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. (1958).

Margesin, R., Schinner, F. & Wilke, B. M. Determination of chemical and physical soil properties. In: Monitoring and Assessing Soil Bioremediation. Soil Biology. 5, 47–95 (2005).

Barr, H. & Weatherley, P. A re-examination of the relative turgidity technique for estimating water deficit in leaves. Australian J. Biol. Sci. 15, 413–428 (1962).

Metzner, H., Rau, H. & Senger, H. Studies on synchronization of some pigment-deficient Chlorella mutants. Planta 65, 186–194 (1965).

Dubois, M., Gilles, K., Hamilton, J., Rebers, P. & Smith, F. Calorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem. 28, 350–356 (1956).

Heath, R. & Packer, L. Photoperoxidation in isolated chloroplasts: I. Kinetics and stoichiometry of fatty acid peroxidation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 125, 189–198 (1968).

Bates, L., Waldren, R. & Teare, L. Rapid determination of free proline for water stress studies. Plant. Soil. 39, 205–207 (1973).

Jindal, K. & Singh, R. Phenolic content in male and female Carica papaya: a possible physiological marker sex identification of vegetative seedlings. Physiol. Plant. 33, 104–107 (1975).

Zou, Y., Lu, Y. & Wei, D. Antioxidant activity of flavonoid-rich extract of Hypericum perforatum L in vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem. 52, 5032–5039 (2004).

Ward, G. M. & Johnston, F. B. Chemical methods of plant analysis. 1064, 59 (1960).

Omar, S. A. et al. Impact of titanium oxide nanoparticles on growth, pigment content, membrane stability, DNA damage, and Stress-Related gene expression in Vicia Faba under saline conditions. Horticulturae 9, 1030 (2023).

Abdelhameed, R. E., Hegazy, H. S., Abdalla, H. & Adarosy, M. H. Efficacy of green synthesized titanium dioxide nanoparticles in Attenuation salt stress in Glycine max plants: modulations in metabolic constituents and cell ultrastructure. BMC Plant. Biol. 25, 221. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-025-06194-6 (2025).

Metwally, R. A. & Soliman, S. A. Alleviation of the adverse effects of NaCl stress on tomato seedlings (Solanum lycopersicum L.) by Trichoderma viride through the antioxidative defense system. Bot. Stud. 64, 4 (2023).

Abdelhameed, R. E., Abdalla, H. & Abdel-Haleem, M. Offsetting Pb induced oxidative stress in Vicia Faba plants by foliar spray of Chitosan through adjustment of morpho-biochemical and molecular indices. BMC Plant. Biol. 24, 557. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-024-05227-w (2024).

Shah, T. et al. Seed priming with titanium dioxide nanoparticles enhances seed Vigor, leaf water status, and antioxidant enzyme activities in maize (Zea Mays L.) under salinity stress. J. King Saud Univ. -Sci. 33, 101207 (2021).

Jaberzadeh, A., Moaveni, P., Moghadam, H. R. T. & Zahedi, H. Influence of bulk and nanoparticles titanium foliar application on some agronomic traits, seed gluten and starch contents of wheat subjected to water deficit stress. Notulae Botanicae Hortiagrobotanici Clujnapoca. 41, 201–207 (2013).

Rafique, R. et al. Dose-dependent physiological responses of Triticum aestivum L. to soil applied TiO2 nanoparticles: alterations in chlorophyll content, H2O2 production, and genotoxicity. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 255, 95–101 (2018).

Abdel Latef, A., Srivastava, A., El-sadek, M., Kordrostami, M. & Tran, L. Titanium. Dioxide nanoparticles improve growth and enhance tolerance of broad bean plants under saline soil conditions. Land. Degrad. Dev. 29, 1065–1073 (2018).

Fuzy, A., Biro, B., Toth, T., Hildebrandt, U. & Bothe, H. Drought, but not salinity, determines the apparent effectiveness of halophytes colonized by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. J. Plant. Physiolgy. 165, 1181–1192 (2008).

Karunanantham, K., Lakshminarayanan, S. P., Ganesamurthi, A. K., Ramasamy, K. & Rajamony, V. R. Arbuscular mycorrhiza-A health engineer for abiotic stress alleviation. Rhizosphere Eng. 171–198 (2022).

Chaudhuri, K. & Choudhuri, M. A. Effects of short-term NaCl stress on water relations and gas exchange of two jute species. Biol. Plant. 40, 373 (1997).

Metwally, R. A. & Abdelhameed, R. E. Synergistic effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in growth and physiology of salt stressed trigonella foenumgraecum plants. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 16, 538–544 (2018).

Lichtenthaler, H. & Buschmann, C. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: Measurement and characterization by UV-VIS spectroscopy. Current protocols in food analytical chemistry. 1, 4 – 3 (2001).

Jaleel, C. et al. Water deficit stress mitigation by calcium chloride in catharanthus roseus: effects on oxidative stress, proline metabolism and Indole alkaloid accumulation. Colloids Surf., B. 60, 110–116 (2007).

Özdemir, F., Bor, M., Demiral, T. & Türkan, I. Effects of 24-epibrassinolide on seed germination, seed-ling growth, lipid peroxidation, proline content and anti-oxidative system of rice (Oryza sativa L.) under salinity stress. Plant. Growth Regul. 42, 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:GROW.0000026509.25995.13 (2004).

Mahmoud, A. W. M., Abdeldaym, E. A., Abdelaziz, S. M., El-Sawy, M. B. I. & Mottaleb, S. A. Synergetic effects of zinc, Boron, silicon, and zeolite nanoparticles on confer tolerance in potato plants subjected to salinity. Agronomy 10, 19 (2020).

Zulfiqar, F. & Ashraf, M. Nanoparticles potentially mediate salt stress tolerance in plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 160, 257–268 (2021).

Elhefnawy, S. M. & Elsheery, N. I. Use of nanoparticles in improving photosynthesis in crop plants under stress. In Photosynthesis. Academic Press. 105–135 (2023).

Redondo-Gómez, S. et al. Growth and photosynthetic responses to salinity of the salt-marsh shrub Atriplex portulacoides. Ann. Bot. 100, 555–563 (2007).

Abd El-Sattar, A. M. & Abdelhameed, R. E. Amelioration of salt stress effects on the morpho-physiological, biochemical and K+/Na+ ratio of Vicia Faba plants by foliar application of yeast extract. J. Plant Nutr. 1–19 (2024).

James, K. R., Cant, B. & Ryan, T. Responses of freshwater biota to rising salinity levels and implications for saline water management: a review. Aust. J. Bot. 51, 703–713 (2003).

Chaves, M., Flexas, J. & Pinheiro, C. Photosynthesis under drought and salt stress: regulatory mechanisms from whole plant to cell. Ann. Bot. 103, 551–560 (2009).

El-Shawa, G., Rashwan, E. & Abdelaal, K. Mitigating salt stress effects by exogenous application of proline and yeast extract on morpho-physiological, biochemical and anatomical characters of calendula plants. Sci. J. Flowers Ornam. Plants. 7, 461–482 (2020).

Oyiga, B. C. et al. Identification and characterization of salt tolerance of wheat germplasm using a multivariable screening approach. J. Agron. Crop. Sci. 202, 472–485 (2016).

Yang, X. et al. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles alleviate polystyrene nanoplastics induced growth Inhibition by modulating carbon and nitrogen metabolism via melatonin signaling in maize. J. Nanobiotechnol. 22, 262 (2024).

Yamori, W., Masumoto, C., Fukayama, H. & Makino, A. Rubisco activase is a key regulator of non-steady‐state photosynthesis at any leaf temperature and, to a lesser extent, of steady‐state photosynthesis at high temperature. Plant J. 71, 871–880 (2012).

Akbari, P. et al. Deoxynivalenol: a trigger for intestinal integrity breakdown. FASEB J. 28, 2414–2429. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.13-238717 (2014).

Mishra, V., Mishra, R. K., Dikshit, A. & Pandey, A. C. Interactions of nanoparticles with plants: an emerging prospective in the agriculture industry. In Emerging technologies and management of crop stress tolerance. Academic press,159–180 (2014).

Sarkar, R. D. & Kalita, M. C. Alleviation of salt stress complications in plants by nanoparticles and the associated mechanisms: an overview. Plant. Stress. 7, 100134 (2023).

Phothi, R. & Theerakarunwong, C. D. Enhancement of rice (Oryza sativa L.) physiological and yield by application of nano-titanium dioxide. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 14, 1157–1161 (2020).

Shabir, S. et al. Deciphering the role of plant-derived smoke solution in ameliorating saline stress and improving physiological, biochemical, and growth responses of wheat. J. Plant Growth Regul. 41, 2769–2786 (2022).

Youssef, S. M. S., Wehedy, M. R., Hafez, M. R. & El-Oksh, I. I. Synergistic interactions of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and Salicylic acid alleviate adverse effects of water salinity on growth and productivity of watermelon via enhanced physiological and biochemical responses. Egypt. J. Hortic. 50, 181–207 (2023).

Khan, T. A., Mazid, M. & Mohammad, F. Status of secondary plant products under abiotic stress. Overv. J. Stress Physiol. Biochem. 7, 75–98 (2011).

Abdoli, S., Ghassemi-Golezani, K. & Alizadeh- Salteh, S. Responses of Ajowan (Trachyspermum Ammi L.) to exogenous Salicylic acid and iron oxide nanoparticles under salt stress. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., 27, 36939–36953.

Alabdallah, N. & Alzahrani, H. The potential mitigation effect of ZnO nanoparticles on [Abelmoschus esculentus L. Moench] metabolism under salt stress conditions. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 27, 3132–3137 (2020).

Farouk, S. & Al-Amri, S. Exogenous zinc forms counteract NaCl- induced damage by regulating the antioxidant system, osmotic adjustment substances, and ions in Canola (Brassica Napus L.) plants. J. Soil. Sci. Plant. Nutr. 19, 887–899 (2019).

Mohamed, A., Hassabo, A., Shaarawy, S. & Hebeish, A. Benign development of cotton with antibacterial activity and metal sorpability through introduction amino Triazole moieties and AgNPs in cotton structure pre-treated with periodate. Carbohydr. Polym. 178, 251–259 (2017).

Abdelaziz, A. M., Salem, S. S., Khalil, A. M. A., El-Wakil, D. A. & Fouda, H. M. Hashem. Potential of biosynthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles to control fusarium wilt disease in eggplant (Solanum melongena) and promote plant growth. Biometals: Int. J. Role Metal Ions Biology Biochem. Med. 35, 601–616. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10534-022-00391-8 (2022).

Abdel Latef, A. A. H., Abu Alhmad, M. F. & Abdelfattah, K. E. The possible roles of priming with ZnO nanoparticles in mitigation of salinity stress in lupine (Lupinus termis) plants. J. Plant Growth Regul. 36, 60–70 (2017).

Abdelhameed, R. E., Abdel Latef, A. A. H. & Shehata, R. S. Physiological responses of salinized Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.) plants to foliar application of Salicylic acid. Plants 10, 657 (2021).

Abobatta, W. F. Plant responses and tolerance to combined salt and drought stress. Salt and drought stress tolerance in plants. Signaling Networks Adapt. Mechanisms, 17–52 (2020).

Ahmad, F., Lau, K. K., Shariff, A. M. & Murshid, G. Process simulation and optimal design of membrane separation system for CO2 capture from natural gas. Comput. Chem. Eng. 36, 119–128 (2012).

Hashem, A., Abd Allah, E., Alqarawi, A., Aldubise, A. & Egamberdieva, D. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhance salinity tolerance of Panicum turgidum Forssk by altering photosynthetic and antioxidant pathways. J. Plant Interact. 10, 230242 (2015).

Ren, H. X. et al. Physiological investigation of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles towards Chinese mung bean. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 7, 677–684 (2011).

Li, Y., Zhang, S., Jiang, W. & Liu, D. Cadmium accumulation, activities of antioxidant enzymes, and malondialdehyde (MDA) content in pistia stratiotes L. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 20, 1117–1123 (2013).

Mohammadi, R. & Maali-Amiri Abbasi. ‘Effect of TiO2 nanoparticles on the effects of nano TiO2 and nano aluminium on wheat 1635 Chickpea response to cold stress’. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 152, 403–410 (2013).

Marslin, G., Sheeba, C. J. & Franklin, G. Nanoparticles alter secondary metabolism in plants via Ros burst. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.00832 (2017).

Chen, T. H. & Murata, N. Enhancement of tolerance of abiotic stress by metabolic engineering of betaines and other compatible solutes. Curr. Opin. Plant. Biol. 5, 250–257 (2002).

Ahanger, M., Hashem, A., Abd-Allah, E. & Ahmad, P. Arbuscular mycorrhiza in crop improvement under environmental stress. In Emerging technologies and management of crop stress tolerance. Academic Press. 69–95 (2014).

Thakur, M. & Sharma, A. D. Salt-stress-induced proline accumulation in germinating embryos: evidence suggesting a role of proline in seed germination. J. Arid Environ. 62, 517–523 (2005).

Rezazadeh, A., Ghasemnezhad, A., Barani, M. & Telmadarrehei, T. Effect of salinity on phenolic composition and antioxidant activity of artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) leaves. J. Med. Plants Res. 6, 245–252 (2012).

Li, J., Ou-Lee, T., Raba, R., Amundson, R. & Last, R. Arabidopsis flavonoid mutants are hypersensitive to UV-B radiation. Plant. Cell. 5, 171–179 (1993).

Lafmejani, Z. N., Jafari, A. A., Moradi, P. & Moghadam, A. L. Impact of foliar application of iron-chelate and iron nano particles on some morpho-physiological traits and essential oil composition of peppermint (Mentha Piperita L). J. Essent. Oil Bearing Plants. 21, 1374–1384 (2018).

Ebadollahi, R., Jafarirad, S., Kosari-Nasab, M. & Mahjouri, S. Effect of explant source, perlite nanoparticles and TiO2/perlite nanocomposites on phytochemical composition of metabolites in callus cultures of Hypericum perforatum. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–15 (2019).

Siddiqui, M. et al. Impact of salt-induced toxicity on growth and yield-potential of local wheat cultivars: oxidative stress and ion toxicity are among the major determinants of salt-tolerant capacity. Chemosphere2 187, 385–394 (2017).

Elhindi, K., El-Din, A. & Elgorban, A. The impact of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in mitigating salt-induced adverse effects in sweet Basil (Ocimum Basilicum L). Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 24, 170–179 (2017).

Ghassemi-Golezani, K. & Abdoli, S. Alleviation of salt stress in rapeseed (Brassica Napus L.) plants by biochar-based rhizobacteria: new insights into the mechanisms regulating nutrient uptake, antioxidant activity, root growth and productivity. Arch. Agron. Soil. Sci. 69, 1548–1565 (2023).

Iqbal, M., Umar, S. & Mahmooduzzafar Nano-fertilization to enhance nutrient use efficiency and productivity of crop plants. Nanomaterials Plant. Potential., 473–505 (2019).

Gohari, G. et al. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) promote growth and ameliorate salinity stress effects on essential oil profile and biochemical attributes of Dracocephalum Moldavica. Sci. Rep. 10, 912 (2020).

Alfei, S., Signorello, M. G., Schito, A., Catena, S. & Turrini, F. Reshaped as polyester-based nanoparticles, Gallic acid inhibits platelet aggregation, reactive oxygen species production and multi-resistant Gram-positive bacteria with an efficiency never obtained. Nanoscale Adv. 1, 4148–4157 (2019).

Zahra, Z. et al. Metallic nanoparticle (TiO2 and Fe3O4) application modifies rhizosphere phosphorus availability and uptake by Lactuca sativa. J. Agric. Food Chem. 63, 6876–6882 (2015).

Ghoto, K., Simon, M. & Shen, Z. J. Physiological and Root Exudation Response of Maize Seedlings to TiO2 and SiO2 Nanoparticles Exposure. BioNanoSci. 10, 473–485 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12668-020-00724-2

Sytar, O., Kumari, P., Yadav, S., Brestic, M. & Rastogi, A. Phytohormone priming: regulator for heavy metal stress in plants. J. Plant Growth Regul. 38, 739–752 (2019).

Tahjib-UI-Arif, M. et al. Differential response of sugar beet to long-term mild to severe salinity in a soil–pot culture. Agriculture 9, 223 (2019).

Parida, A. & Das, A. Salt tolerance and salinity effects on plants: A review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 60, 324–349 (2005).

Azooz, M., Youssef, A. & Ahmad, P. Evaluation of Salicylic acid (SA) application on growth, osmotic solutes and antioxidant enzyme activities on broad bean seedlings grown under diluted seawater. Int. J. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 3, 253–264 (2011).

Wu, S. G. et al. Electrospray facilitates the germination of plant seeds. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 14, 632–641 (2014).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HSH, HA, REA and MHA: sharing in conceptualization and methodology. REA and MHA: data curation. REA sharing in writing, reviewing and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdelhameed, R.E., Abdalla, H., Hegazy, H.S. et al. Interpreting the potential of biogenic TiO2 nanoparticles on enhancing soybean resilience to salinity via maintaining ion homeostasis and minimizing malondialdehyde. Sci Rep 15, 12904 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94421-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94421-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Multifaceted role of Moringa oleifera leaf extract as antimicrobial, growth enhancer and mitigator of salt stress in tomato seedlings

BMC Plant Biology (2025)

-

Acclimatization of Cicer arietinum L. plants to salinity: examining the relief role of autochthonous mycorrhiza and exogenous proline

BMC Plant Biology (2025)

-

Selenium Seed Priming Adjusts Photosynthesis, Metabolic Constituents and Gene Expression Profiling in Vicia faba L to Outstand Lead Stress

Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition (2025)

-

PuWRKY21 is crucial as a negative regulatory factor in response to drought stress in poplar

Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) (2025)