Abstract

This study looks at two photonic crystals that are similar to Cantor’s and are separated by a thin layer of sensitive, porous silicon made of poly(ethylene oxide) nanocomposite and potassium iodide, which is used as a gamma indicator. Modifications in the distinct peak versus the irradiation dose track how the proposed indicator responds to radiation. The results demonstrate that gamma radiation alters the refractive index of the poly(ethylene oxide) nanocomposite, causing the distinct peaks to shift. The impact of doping of nanocomposite with potassium iodide, the porosity of silicon, and the cell’s number is analyzed. Doping the sensitive nanocomposite with potassium iodide showed a negative effect. The proposed indicator recorded a high sensitivity of 0.218 nm/Gy (nm/Gy = nanometer/gray) for low gamma doses up to 100 Gy, and a moderated sensitivity of 0.13 nm/Gy for high gamma dose from 100 to 200 Gy. The suggested indicator demonstrated high sensitivity in low gamma detection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A lot of scientists are interested in both periodic and non-periodic photonic crystals (PCs), which are made of dielectric materials that change their refractive indices (RIs) over time1,2,3,4,5,6. The regular configuration of the RIs results in the photonic bandgap (PBG), which is the most notable characteristic of PCs7,8,9,10. A specific wavelength or frequency of propagating electromagnetic waves (EMWs) will not be allowed to pass through PCs and be reflected within the range of PBG11,12. 1D-PCs are constructed materials with different RIs, arranged in alternate multilayered patterns. 1D-PCs offer effective purposes in different fields of sensors, smart windows, etc. Porous silicon (PSi) has garnered increasing attention in several sectors and PC structures due to its high sensitivity (S) and large surface area13,14,15. PSi preparation technology is one of the quickest and easiest ways to create PC structures13,14. A quasi-configuration that has gained significant interest in detection fields is the Cantor sequence PCs (CS-PCs)16,17,18. Zaky et al.19 proposed a RI detector with outstanding performance using a CS-PC configuration of gyroidal graphene and PSi. The unique properties and advantage of CS-PC configuration is the ability to simultaneously establish a coupling between many types of resonance. This coupling strongly enhances the sensitivity of sensors19.

Highly efficient solid-state detectors for radiation are widely used in various fields, including scientific investigations, industrial inspection, military purposes, medical diagnostics, and therapy20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. One of the most popular detectors for data collection is the photodetector28. Gamma radiation has been employed extensively in numerous medical dosimetry for stereotactic radiosurgery29, environmental monitoring30, industrial31, and others applications32,33. Nuclear power plants must continuously monitor environmental pollutants, both within and outside their boundaries, to control radiation pollution34.

Polymer nanocomposites (PNCs) can be prepared by forming ionic chain or networks within the geometry of polymers by dissolving salts within the matrix of polymers35. PNCs have emerged as a potentially useful class of energy storage and conversion application components. PNC’s distinct structures offer excellent ionic conductivity, great mechanical and thermal stability, and broad electrochemical stability. PNCs have attracted more attention as active materials in potential applications, including batteries, supercapacitors, fuel cells, and radiation detectors35,36,37,38,39. PNCs are low-cost, flexible, and can be simply formed into films. Bich et al.40 used indigo dye samples for radiation sensing with \(S =0.0002\)nm/Gy. Zaky et al.41 designed a CS-PC using PSi contains a polymer of Poly Vinyl Alcohol, carbol fuchsin, and crystal violet to detect gamma radiation. Besides, Kher et al.42 discussed the ability to use long-period gratings as a radiation detector with \(S = 0.00018\) nm/Gy. A radiation detector with \(S =0.0012\)nm/Gy was practically and theoretically built in 2018 by Stancalie et al.43 utilizing long-period gratings.

Using PCs in gamma detection is a cutting-edge approach to improve radiation detection systems’ sensitivity, selectivity, and functionality. Furthermore, PCs allow for the miniaturization of gamma detectors while maintaining high performance and open the door to portable or embedded radiation detection systems. In order to detect and measure radioactive items in public areas, shipping containers, and security checkpoints, high-sensitivity gamma detectors are essential. They can help protect national and international security by spotting the illegal movement of nuclear materials.

In this study, CS-PCs separated by a sensitive PSi layer doped with poly nanocomposite of ethylene oxide (PNCEO) is designed as a gamma indicator. The RIs of PNCEO before and after irradiation at different concentrations of potassium iodide (KI) are fitted from experimental data35. The effect of doping PNCEO with different concentrations of KI is investigated. Besides, number of CS-PCs cells and the porosity of PSi are investigated to achieve high performance. The proposed detector offers high sensitivity, excellent Q-factor, and strong performance in low-dose gamma detection, making it a promising candidate for precise and reliable radiation monitoring applications.

Theoretical model and basic equations

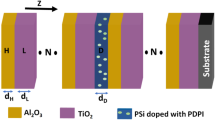

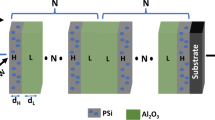

This section outlines the theoretical framework and key equations utilized to analyze the data and interpret the results. Figure 1 is the schematic representation of CS-PC defected with nanocomposite of poly(ethylene oxide) doped with Potassium Iodide as Cantor 1D-PC of \(\left[\text{A}\text{i}\text{r}\text{*}{\left(\text{H}\text{L}\text{H}\text{L}\text{L}\text{L}\text{H}\text{L}\text{H}\right)}^{N}\text{*}\text{D}\text{*}{\left(\text{H}\text{L}\text{H}\text{L}\text{L}\text{L}\text{H}\text{L}\text{H}\right)}^{N}\text{*}\text{S}\text{i}\:\text{S}\text{u}\text{b}\text{s}\text{t}\text{r}\text{a}\text{t}\text{e}\right]\). Layers H, L, and D are \(Ti{O}_{2}\), \({Al}_{2}{O}_{3}\), and PSi contains PNCEO, respectively. The thicknesses of high RI (\(H\)), low RI (\(L\)) and defect (\(D\)) layers are 200 nm, 150 nm, and 110 nm, respectively. The porosity of PSi layer is 10% (as initial condition and it will be optimized later). \(N=5\) denotes how many times the cantor sequence is repeated. θ of 0 degrees is the angle of incidence of EMWs from air to CS-PC. The RIs of substrate and air are 1.52 (SiO2) and 1, respectively. As will be discussed in the “Results and discussion” section, the above parameters are selected to adjust the PBG in the stable range of refractive indices. PNCEO is considered a sensitive medium for radiation. Doping of PNCEO in silicon is done to control the sensitivity and prevent the overlap of peaks, as we will discuss later.

The RIs of \(Ti{O}_{2}\), and \({Al}_{2}{O}_{3}\) can be calculated as follows (\(\lambda\) in µm)44:

Bruggeman’s effective equations are utilized for calculating the PSi RI45:

where \({\text{n}}_{\text{S}\text{i}} =3.7\) and \(P\) is the ratio of PNCEO in PSi. The final form of PSi layers will not contain pores. It will be Si doped with polymer. The effect of gamma radiation on \(Si\), \(Ti{O}_{2}\), and \({Al}_{2}{O}_{3}\) can be neglected44,46,47. The refractive indices of PNCEO before and after exposure to gamma radiation at various KI concentrations can be determined within the range of 0.30 μm to 0.80 μm35:

For 0 Gy of Gamma radiation:

At 0% KI:

At 2% KI:

At 6% KI:

At 10% KI:

At 15% KI:

For 100 Gy of Gamma radiation:

At 0% KI:

At 2% KI:

At 6% KI:

At 10% KI:

At 15% KI:

For 200 Gy of Gamma radiation:

At 0% KI:

At 2% KI:

At 6% KI:

At 10% KI:

At 15% KI:

The above equations are fitted from experimental data35 using nonlinear least squares fitting. This method minimizes the difference between the experimental data and the predicted Sellmeier equations. KI was chosen for the initial investigation because PNCEO films are frequently prepared using KI salts as a dopant to enhance the conductivity of PNCEO films. The conductivity of PNCEO films is enhanced because the negative charges on the PEO chains are neutralized by the counterion function of the K+ ve ions. Besides, I− ve ions have the ability to help PEO chains create complex ions, which will further increase conductivity35.

The transfer matrix method (TMM) will be used to find the transmittance (T) of transverse electric (TE) EMWs moving through the CS-PC detector before and after gamma radiation3,48,49,50:

where,

where \({p}_{0}\) is for air and \({p}_{s}\) is for substrate. TMM has already been applied to design sensors19,51,52,53,54, filters55, and other simulations.

Wang et al.56 investigated the reflectance of a 1D reflector using 1DPC both theoretically and empirically (using TMM) with very good matches. Gutierrez et al.57 modeled and fabricated a chemical, optical, and thermal sensor. The experimental and numerical (using TMM) results coincided with each other.

Results and discussion

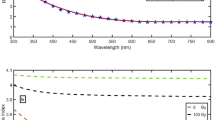

This section presents the results of the study, including the impact of gamma radiation on the refractive index and the performance of the proposed dosimeter. A detailed discussion of the findings and their implications is provided. Figure 2A–E shows the RIs of PNCEO at different doses from 0 Gy to 100 Gy, and 200 Gy by changing the concentration of KI in PNCEO from 0 to 2%, 6%, 10%, and 15%. By growing the gamma doses from 0 to 200 Gy, RI of PNCEO substantially increases. When gamma rays hit polymer composites, they break chains, which leads to changes such as cross-linking, releasing, absorption by carbon, formation of interband states, a smaller energy gap, and a higher RI58,59. The inverse relation between RI and energy gap theoretically agrees with Penn model60.

Fitted and measured35 RIs of PNCEO at different doses (0 Gy, 100 Gy, and 200 Gy) by changing the concentration of KI in PNCEO from (A) 0%, (B) 2%, (C) 6%, (D) 10%, and (E) 15%.

The RIs of PSi doped with 10% of PNCEO at different doses from 0 Gy to 100 Gy, and 200 Gy with changing the concentration of KI in PNCEO from 0%, to 2%, 6%, 10%, and 15% are clear in Fig. 3A–E. As clear in Fig. 2, by increasing the gamma doses, the RI of PNCEO substantially increases, and the RIs of PSi doped with 10% of PNCEO increase, according to Eq. (3). For wavelengths lower than 550 nm, the RI of PSi strongly decreases versus wavelength. For \(550\:nm\le\lambda \le 800\:nm\), the RI of PSi seems more stable. As a result, the range of wavelengths of \(550\:nm\le \lambda \le 800\:nm\) is a good choice for the proposed detector. At 800 nm and gamma doses of 0 Gy, the RI of PSi increases from 3.480 to 3.522, 3.555, 3.602, and 3.667 with changing the concentration of KI in PNCEO from 0%, to 2%, 6%, 10%, and 15%. For gamma doses of 100 Gy, the RI of PSi increases from 3.922 to 3.933, 3.952, 3.959, and 3.967 with changing the concentration of KI in PNCEO from 0%, to 2%, 6%, 10%, and 15%. For gamma doses of 200 Gy, the RI of PSi increases from 4.043 to 4.052, 4.071, 4.076, and 4.146 with changing the concentration of KI in PNCEO from 0%, to 2%, 6%, 10%, and 15%.

It can be observed that the change in RI of PSi due to changing gamma doses from 0 Gy to 200 Gy is 0.563, 0.530, 0.516, 0.474, and 0.479 at concentrations of KI in PNCEO from 0%, to 2%, 6%, 10%, and 15%, respectively. This means that doping PNCEO with KI has a negative effect on the change in RI of PSi due to changing gamma doses from 0 Gy to 200 Gy. As the idea of the proposed detector builds on the RI change of defect layer (PSi doped with PNCEO), PSi layer will be doped with PNCEO at 0% concentration of KI.

Through simulating a CS-PC without a defect cavity using the transfer matrix method (TMM) (Fig. 4A), a photonic bandgap (PBG) extends from 592.3 nm to 617.2 nm due to the refractive index difference between the layers. Separating two CS-PC with a \(PSi\) doped with PNCEO defect creates a distinct peak inside the PBG at 598.5 nm. By increasing the gamma doses from 0 Gy to 100 Gy, and 200 Gy, the RI of PSi doped with 10% of PNCEO substantially increases, and the distinct peak is shifted from 598.5 nm to 605.9 nm, and 607.8 nm, as clear in Fig. 4B. This dependence between the effective RI of the device and distinct peak position (\({\lambda }_{d}\)) is explained according to the standing wave relation:

where \(\:m\) and D are integer and geometric path difference. By increasing RI of doped PSi of defect, the effective RI increases, and the \(\:{\lambda\:}_{d}\) increases. Any sensor begins to function better when it has low bandwidth (FWHM), high S, high quality-factor (Q), high figure of merit (FoM), and low detection limit (LoD) according to the following formulas:

As clear in Figs. 5A–E and 6B, increasing the porosity of the defect layer of PSi doped with PNCEO from 10 to 15%, 20%, 25%, and 30% increases the shift between distinct peaks. This increase in shift (\(\varDelta\:{\lambda}_{d}\)) enhances the sensitivity and the function of the sensor. Besides, the transmittances of all distinct peaks are near to 100% due to the good confinement of incident EMW in the cavity of PSi layer, as clear in Fig. 6A. On the right axis of Fig. 6A, increasing the shift moves the distinct peak of 0 Gy close to the left edge of the PBG. As a result, the FWHM increases gradually with increasing the porosity of the defect layer of the PSi doped with PNCEO from 10 to 30%. As FoM and Q have inverse relations with FWHM, they decrease, as clear in Fig. 6B, C. Finally, LoD gradually increases with decreasing Q, according to Eq. (27). If the porosity exceeds 30%, the distinct peaks will no longer be within the photonic bandgap (PBG). So, the porosity of 30% will be selected as a suitable condition.

As the is FWHM adversely affected by increasing porosity, N will be exploited to decrease FWHM and make the edges of PBG sharper. Figure 7A–E clear the positive effect of N on decreasing FWHM. It is noted that increasing N higher than 8 cells negatively affects the distinct peak of 100 Gy gamma dose due to backscattering and absorption. At \(N=9\) and 10, the transmittance of 100 Gy gamma dose is 58% and 2%, respectively. The transmittance seems to be unaffected for distinct peaks of 0 Gy and 200 Gy gamma doses. Increasing the cell’s units from 6 to 10 didn’t affect the transmittance of distinct peaks at 0 Gy gamma doses, as clear in Fig. 8A. On the right axis of Fig. 8A, increasing N from 6 cells to 10 cells decreases FWHM from 0.325 nm to 0.009 nm. As a result, FoM and Q increase, as clear in Fig. 8B, C. However, it was unaffected by the changing of N because the position of distinct peaks didn’t change. LoD gradually decreases with increasing Q, according to Eq. (27).

From the above investigations, N of 9 cells on both sides of the PSi defect layer is suitable. And yet, they will be verified to ensure that all intermediate values of radiation doses will have suitable transmittance. As we don’t have the RIs of PNCEO at intermediate gamma doses, the RIs of PNCEO at 0 Gy, 100 Gy, and 200 Gy will be determined, and intermediate RIs will be selected. The refractive indices of PSi doped with PNCEO are 3.04, 4.42, and 4.89 at the positions corresponding to 0 Gy, 100 Gy, and 200 Gy, respectively. By taking intermediate RIs, many peaks have very low transmittance, as clear in Fig. 9. So, these conditions are not satisfied for a suitable detector.

Besides, a wide PBG is observed at higher wavelengths extended from 724.8 nm to 767.3 nm. By controlling the thickness of the defect (at \({d}_{D}=150\:nm\)), all distinct peaks are adjusted inside the PBG in the correct order. By the same way, at \({\lambda}_{d}=727.91\:\text{n}\text{m}\) (the position of 0 Gy), \({\lambda}_{d}=749.70\:\text{n}\text{m}\) (the position of 100 Gy), and \({\lambda}_{d}=762.82\:\text{n}\text{m}\) (the position of 200 Gy), the RIs of PSi doped with PNCEO is 3.02, 4.41, and 4.88, respectively. By taking intermediate RIs, all peaks have good transmittance, as clear in Fig. 10. So, these conditions are satisfied for a suitable detector.

When transitioning from 0 Gy to 100 Gy of gamma radiation, the transmittance of the distinct peak decreases from 96.1 to 88.1%, while the peak shifts from 727.91 nm to 749.70 nm. Additionally, the full width at half maximum (FWHM) increases from \(1.2\times{10}^{-2}\) nm to \(4.4\times{10}^{-4}\) nm, sensitivity is 0.22 nm/Gy, figure of merit (FoM) is 490 \({\text{G}\text{y}}^{-1}\), quality factor (Q) improves, and the limit of detection (LoD) is \(1.02\times{10}^{-4}\) Gy. With increasing the gamma doses from 100 Gy to 200 Gy, the transmittance of the distinct peak increases from 88.1 to 98.5%, the position of the distinct peak is moved from 749.70 nm to 762.82 nm, the FWHM is enhanced from \(4.4\times {10}^{-4}\) nm to \(2.8 \times {10}^{-2}\) nm, the sensitivity is 0.13 nm/Gy, the FoM is 4.65 \({\text{G}\text{y}}^{-1}\), the Q enhanced from \(1.7 \times {10}^{6}\) to \(2.7 \times {10}^{4}\), and LoD is \(1.08 \times {10}^{-2}\) Gy. The decrease in sensitivity at doses exceeding 100 Gy, as shown in Fig. 10, may be attributed to the nonlinear response of the polymer refractive index to gamma radiation35. Table 1 clearly shows that the proposed gamma dose detector containing a defect of PSi doped with 30% of PNCEO has excellent performance in gamma detection, such as sensitivity and Q-factor.

The results of this study demonstrate that the optimal design for a highly sensitive gamma radiation detector consists of a defect layer of PSi doped with 30% PNCEO, without KI doping, and an optimum number of 8 photonic crystal cells. The findings indicate that KI doping negatively impacts detector performance, reducing both sensitivity and Q-factor. The proposed detector exhibits high sensitivity of 0.218 nm/Gy and a Q-factor of 1,686,804 for low gamma doses (0–100 Gy), making it highly suitable for low-dose detection applications. For higher gamma doses (100–200 Gy), the sensor maintains a moderate sensitivity of 0.131 nm/Gy with a Q-factor of 27,050, ensuring continued functionality but with reduced efficiency. These results suggest that the designed detector is particularly effective for low-dose gamma radiation detection, with the potential for further optimization in higher dose applications.

Conclusion

The study presented CS-PCs separated by a sensitive PSi layer doped with PNCEO as a gamma indicator. Doping PNCEO with KI has a negative effect on the sensor’s performance. On the other hand, the number of cells, porosity, and thickness of the defect PSi layer are tuned to maximize the indicator performance. This gamma indicator can discriminate between different gamma doses accurately and simultaneously. The proposed detector has a relatively high sensitivity of 0.218 nm/Gy for low doses (from 0 Gy to 100 Gy) and a moderated sensitivity of 0.131 nm/Gy for higher gamma doses (from 100 Gy to 200 Gy). A comparison with similar studies illustrates the exceptional feature of the suggested gamma indicator.

Data availability

Requests for materials or code should be addressed to Zaky A. Zaky.

References

Starkey, T. & Vukusic, P. Light manipulation principles in biological photonic systems. Nanophotonics 2, 289–307. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2013-0015 (2013).

Ameen, A. A., Al-Dossari, M., Zaky, Z. A. & Aly, A. H. Studying the effect of quantum dots and parity-time symmetry on the magnification of topological edge state peak as a pressure sensor. Synth. Met. 292, 117233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.synthmet.2022.117233 (2023).

Yeh, P. Optical Waves in Layered Media (Wiley, 1988).

John, S. Strong localization of photons in certain disordered dielectric superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 58, 2486. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.58.2486 (1987).

Al-Dossari, M., Zaky, Z. A., Awasthi, S. K., Amer, H. A. & Aly, A. H. Detection of glucose concentrations in urine based on coupling of Tamm–Fano resonance in photonic crystals. Opt. Quant. Electron. 55, 484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-023-04621-2 (2023).

Zaky, Z. A., Al-Dossari, M., Sharma, A. & Aly, A. H. Effective pressure sensor using the parity-time symmetric photonic crystal. Phys. Scr. 98, 035522. https://doi.org/10.1088/1402-4896/acbcae (2023).

Foulger, S. H. et al. Photonic crystal composites with reversible high-frequency stop band shifts. Adv. Mater. 15, 685–689. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.200304566 (2003).

Wang, Y. et al. Biomaterial-Based structured opals with programmable combination of diffractive optical elements and photonic bandgap effects. Adv. Mater. 31, 1805312. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201805312 (2019).

Zaky, Z. A. et al. Photonic crystal with magnified resonant peak for biosensing applications. Phys. Scr. 98, 055108. https://doi.org/10.1088/1402-4896/accbf1 (2023).

Zaky, Z. A. et al. Theoretical optimization of Tamm plasmon polariton structure for pressure sensing applications. Opt. Quant. Electron. 55, 738. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-023-05023-0 (2023).

Zaky, Z. A. et al. Theoretical analysis of porous silicon one-dimensional photonic crystal doped with magnetized cold plasma for hazardous gases sensing applications. Opt. Quant. Electron. 55, 584. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-023-04907-5 (2023).

Zaky, Z. A., Al-Dossari, M., Zhaketov, V. & Aly, A. H. Defected photonic crystal as propylene glycol THz sensor using parity-time symmetry. Sci. Rep. 14, 23209. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73477-7 (2024).

Ariza-Flores, A. D., Gaggero-Sager, L. & Agarwal, V. Effect of interface gradient on the optical properties of multilayered porous silicon photonic structures. J. Phys. D. 44, 155102. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/44/15/155102 (2011).

Huanca, D. R. One-dimensional porous silicon photonic crystals, in Silicon Nanomaterials Sourcebook 3–42 (CRC, 2017).

Kim, K., Lenshin, A., Chyragov, F. & Niftaliev, S. Formation of nanostructured tin oxide film on porous silicon. Azerbaijan Chem. J., 83–89 (2023).

Augustyniak, A., Zdanowicz, M. & Osuch, T. Self-similarity properties of complex quasi-periodic fibonacci and cantor photonic crystals. Photonics, 558. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics8120558 (2021).

Wu, M., Liu, F., Zhao, D. & Wang, Y. Unidirectional Invisibility in PT-symmetric cantor photonic crystals. Crystals 12, 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst12020199 (2022).

Liu, J., Shen, J., Zhao, D. & Zhang, P. Photonic passbands induced by optical fractal effect in cantor dielectric multilayers. PloS One. 17, e0268908. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0268908 (2022).

Zaky, Z. A., Al-Dossari, M., Matar, Z. & Aly, A. H. Effect of geometrical and physical properties of cantor structure for gas sensing applications. Synth. Met. 291, 117167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.synthmet.2022.117167 (2022).

Kasap, S. et al. Amorphous and polycrystalline photoconductors for direct conversion flat panel X-ray image sensors. Sensors 11, 5112–5157. https://doi.org/10.3390/s110505112 (2011).

Kim, Y. C. et al. Printable organometallic perovskite enables large-area, low-dose X-ray imaging. Nature 550, 87–91. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature24032 (2017).

Omar, A., Baraka, A., Zaki, A. H. & Sharshar, K. A. Absorbance and conductivity of aniline hydrochloride/polyvinyl alcohol films (An/PVA) for high level gamma radiation dosimetry from 2 kGy up to 10 kGy. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 9, 513–521 (2014).

Omar, A., Baraka, A., Zaki, A. H. & Sharshar, K. A. Gamma radiation effect on the electrical properties of PANI film. Appl. Mech. Mater. 241, 828–832. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.241-244.828 (2013).

Omar, A., Baraka, A., Zaki, A. H. & Sharshar, K. A. Metal oxide films/structures for gamma radiation detection. in IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Circuits, and Systems (ICECS), 685–688. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICECS.2015.7440409 (2015).

Omar, A., Baraka, A., Zaki, A. H. & Sharshar, K. A. Absorbance and conductivity of aniline hydrochloride/polyvinyl alcohol films (AN/PVA) for gamma radiation dosimetry in the range 0–10 kGy. In The International Conference on Chemical and Environmental Engineering, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.21608/iccee.2012.35889 (2012).

Omar, A., Baraka, A., Zaki, A. H. & Sharshar, K. A. Aluminum oxide doped/Aniline hydrochloride films for gamma radiation detection. In International Conference on Aerospace Sciences and Aviation Technology, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.21608/asat.2015.22953 (2015).

Tawfik, A. F., Baraka, A. A., Gobara, M. M. & Omar, A. M. Potential use of aqueous solution of tartarzine dye as low-dose dosimeter for gamma radiation. In The International Conference on Chemical and Environmental Engineering, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.21608/iccee.2010.37357 (2010).

Sellan, P. et al. Preparation of bismuth-doped CsPbBr 3 perovskite single crystals for X-ray and gamma-ray sensing applications. Mater. Adv. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4MA00455H (2024).

Park, J. H. et al. Application of the gamma evaluation method in gamma knife film dosimetry. Med. Phys. 38, 5778–5787. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.3641644 (2011).

Losana, M. C., Magnoni, M. & Righino, F. Comparison of different methods for the assessment of the environmental gamma dose. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 97, 333–336. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.rpd.a006683 (2001).

McLaughlin, W. L., Humphreys, J. C. & Miller, A. Dosimetry for industrial radiation processing. In NBS Special Publication 609 Proceedings of a Meeting on Traceability of Ionizing Radiation Measurements, 171 (1982).

Procz, S. et al. X-ray and gamma imaging with Medipix and timepix detectors in medical research. Radiat. Meas. 127, 106104 (2019).

Theodorakou, C. & Farquharson, M. J. Human soft tissue analysis using X-ray or gamma-ray techniques. Phys. Med. Biol. 53, R111 (2008).

Kumar, K. P., Sundaram, G. S., Sharma, B., Venkatesh, S. & Thiruvengadathan, R. Advances in gamma radiation detection systems for emergency radiation monitoring. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 52, 2151–2161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2020.03.014 (2020).

Qwasmeh, A. A. H. et al. Effects of gamma irradiation on optical properties of poly (ethylene oxide) thin films doped with potassium iodide. J. Compos. Sci. 7, 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs7050194 (2023).

Hamsan, M., Shukur, M., Aziz, S. B., Yusof, Y. & Kadir, M. Influence of NH _ 4 NH 4 Br as an ionic source on the structural/electrical properties of dextran-based biopolymer electrolytes and EDLC application. Bull. Mater. Sci. 43, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12034-019-2008-9 (2020).

Aziz, S. B. et al. Effect of ohmic-drop on electrochemical performance of EDLC fabricated from PVA: dextran: NH4I based polymer blend electrolytes. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 9, 3734–3745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.01.110 (2020).

Hamsan, M. et al. Solid-state double layer capacitors and protonic cell fabricated with dextran from leuconostoc mesenteroides based green polymer electrolyte. Mater. Chem. Phys. 241, 122290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2019.122290 (2020).

Aziz, S. B. et al. Fabrication of energy storage EDLC device based on CS: PEO polymer blend electrolytes with high Li + ion transference number. Results Phys. 15, 102584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinp.2019.102584 (2019).

Bich, T., Mallam, S., Diso, D. & Hotoro, M. Determination of threshold radiation dose in the degradation process of indigo dye by gamma irradiation technique. J. Phys. Sci. Innov. 5, 15–22 (2013).

Zaky, Z. A., Al-Dossari, M., Hendy, A. S., Zayed, M. & Aly, A. H. Gamma radiation detector using cantor quasi-periodic photonic crystal based on porous silicon doped with polymer. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 38, 2450409. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217979224504095 (2024).

Kher, S., Chaubey, S., Kashyap, R. & Oak, S. M. Turnaround-point long-period fiber gratings (TAP-LPGs) as high-radiation-dose sensors. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 24, 742–744. https://doi.org/10.1109/LPT.2012.2187637 (2012).

Stăncălie, A. et al. Long period gratings in unconventional fibers for possible use as radiation dosimeter in high-dose applications. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 271, 223–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sna.2018.01.034 (2018).

Esposito, F. et al. Optical properties of thin films monitored in real-time at high gamma radiation doses using long period fiber gratings. Opt. Laser Technol. 176, 111019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2024.111019 (2024).

Zaky, Z. A., Alamri, S., Zhaketov, V. & Aly, A. H. Refractive index sensor with magnified resonant signal. Sci. Rep. 12, 13777. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-17676-0 (2022).

Sayed, F. A., Elsayed, H. A., Mehaney, A., Eissa, M. & Aly, A. H. A doped-polymer based porous silicon photonic crystal sensor for the detection of gamma-ray radiation. RSC Adv. 13, 3123–3138. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2RA07637C (2023).

Du, Q. et al. Gamma radiation effects in amorphous silicon and silicon nitride photonic devices. Opt. Lett. 42, 587–590. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.42.000587 (2017).

Zaky, Z. A., Alamri, S., Zohny, E. I. & Aly, A. H. Simulation study of gas sensor using periodic phononic crystal tubes to detect hazardous greenhouse gases. Sci. Rep. 12, 21553. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-26079-0 (2022).

Zaky, Z. A., Al-Dossari, M., Hendy, A. S. & Aly, A. H. Studying the impact of interface roughness on a layered photonic crystal as a sensor. Phys. Scr. 98, 105527. https://doi.org/10.1088/1402-4896/acfa4a (2023).

Zaky, Z. A., Zhaketov, V., Sallah, M. & Aly, A. H. Using periodic multilayers of ferromagnetic and paramagnetic layers as neutron filter: simulation study. Plasmonics, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11468-024-02533-9 (2024).

Zaky, Z. A., Singh, M. R. & Aly, A. H. Tamm resonance excited by different metals and graphene. Photonics Nanostruct.-Fundam. Appl. 49, 100995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.photonics.2022.100995 (2022).

Zaky, Z. A., Amer, H. A., Suthar, B. & Aly, A. H. Gas sensing applications using magnetized cold plasma multilayers. Opt. Quant. Electron. 54, 217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-022-03594-y (2022).

Zaky, Z. A., Al-Dossari, M., Zohny, E. I. & Aly, A. H. Refractive index sensor using fibonacci sequence of gyroidal graphene and porous silicon based on Tamm plasmon polariton. Opt. Quant. Electron. 55, 6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-022-04262-x (2023).

Zaky, Z. A., Hanafy, H., Panda, A., Pukhrambam, P. D. & Aly, A. H. Design and analysis of gas sensor using tailorable fano resonance by coupling between tamm and defected mode resonance. Plasmonics 17, 2103–2111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11468-022-01699-4 (2022).

Zaky, Z. A. & Aly, A. H. Novel smart window using photonic crystal for energy saving. Sci. Rep. 12, 10104. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14196-9 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. 1D partially oxidized porous silicon photonic crystal reflector for mid-infrared application. J. Phys. D. 40, 4482. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/40/15/016 (2007).

Ramirez-Gutierrez, C. F., Martinez-Hernandez, H. D., Lujan-Cabrera, I. A. & Rodriguez-García, M. E. Design, fabrication, and optical characterization of one-dimensional photonic crystals based on porous silicon assisted by in-situ photoacoustics. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-51200-1 (2019).

Abdul-Kader, A. The optical band gap and surface free energy of polyethylene modified by electron beam irradiations. J. Nucl. Mater. 435, 231–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2013.01.287 (2013).

Abu Saleh, B. A., Elimat, Z. M., Alzubi, R. I., Juwhari, H. K. & Zihlif, A. M. Ultrafine iron particles/polystyrene composites: effects of gamma radiation and manufacture aging on the AC electrical characterization. Radiat. Eff. Defects Solids. 177, 1065–1074. https://doi.org/10.1080/10420150.2022.2105217 (2022).

Penn, D. R. Wave-number-dependent dielectric function of semiconductors. Phys. Rev. 128, 2093. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.128.2093 (1962).

Esposito, F., Srivastava, A., Campopiano, S. & Iadicicco, A. Radiation effects on long period fiber gratings: A review. Sensors 20, 2729. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20092729 (2020).

Ibrahim, M. S. S., Hamed, M. K. G., El-Okr, M. M., Obayya, S. & Hameed, M. F. O. Highly sensitive photonic crystal gamma ray dosimeter. Opt. Quant. Electron. 53, 348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-021-02968-y (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at University of Bisha for supporting this work through the Fast-Track Research Support Program. The authors acknowledge the joint project between the Academy of scientific research and technology (Egypt) and the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (Dubna - Russia) ASRT-JINR collaboration.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.A. Zaky invented the original idea of the study, implemented the computer code, performed the numerical simulations, analyzed the data, wrote and revised the main manuscript text, and was the team leader. T. S. Hassan analyzed the data, discussed the results, and co-wrote the revised manuscript. V. D. Zhaketov analyzed the data and discussed the results. M. S. El Tokhy analyzed the data and discussed the results. M. Sallah analyzed the data and discussed the results. Finally, all Authors developed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

This article does not contain any studies involving animals or human participants performed by any authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zaky, Z.A., Hassan, T.S., Zhaketov, V.D. et al. Theoretical study of doped porous silicon in cantor quasi periodic structure for gamma radiation detection. Sci Rep 15, 14995 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94555-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94555-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Using Thue Morse structure and magnified defect resonance as cancer sensor

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Terahertz metasensor with pseudo parity time symmetry for oral cancer diagnostics

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Oral cancer biosensor using ternary photonic crystal and parity time symmetry

Scientific Reports (2025)