Abstract

With improvements in industrial automation, the reliability of the gearbox, a key transmission device, has become increasingly crucial for the stable operation of an entire operating system. However, predicting the remaining useful life of the gearbox is challenging because of complex working environments and dynamic load changes. Several existing methods assume an inaccurate model structure and parameter estimation during life prediction, owing to the limited availability of similar fault sample data. In this study, we analyse the influence of kernel density estimation (KDE) based on time-varying distribution on the results of residual useful life prediction, considering the characteristics of such systems and the problems faced by current research methods. First, a time-varying KDE model with an incremental distribution of degradation features is established, and the influence of sample timing on KDE is introduced. Second, the exponential weighted moving average method is employed to predict the degraded samples, and recursive update was employed to reduce unnecessary double calculations during the estimation of the time-varying weight kernel density in the system operation process. Finally, the adaptability and effectiveness of the proposed method are verified using actual collected gearbox data. Research results indicate that the remaining useful life prediction outcomes of the method proposed in this paper are superior to those of the DGN model and the Ensemble model, as evidenced by its lower RMSE and MAE values.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The complexity and precision of mechanical systems have undergone continuous development; however, the probability and types of failures of these systems have also increased. In particular, a sudden failure of the gearbox, a critical transmission device, may interrupt the operation of the entire system, which can adversely affect production management and even endanger personal safety1,2. Therefore, from the perspective of industrial big data, effective monitoring and evaluation of the remaining system life are essential3. Several studies have focused on predicting the remaining useful life (RUL) as the core of prognostics and health management4.

Various residual life prediction methods have been widely used, including methods based on physical mechanisms, expert prior knowledge, and data-driven approaches5,6,7. Physical models8,9 are often challenging to establish for complex mechanical equipment, as the requisite expert knowledge is difficult to acquire10,11. Therefore, data-driven life prediction methods are becoming increasingly prevalent. Yan et al.12 utilised support vector machines to establish a degradation model for predicting the residual life. Yang et al.13 modelled the degradation state of components as a discrete semi-Markov process. Hu et al.14 reviewed residual life prediction models, such as regression, proportional risk, stochastic filter, and hidden Markov models, considering data-driven aspects. Several monotonous degradation processes that represent the development of wear or cracks in a system have been modelled as Gamma processes15,16,17. However, these data-driven prediction methods typically make assumptions regarding the model structure18,19, and a significant gap often exists between an actual process and assumption-based degradation models. The optimisation of parameter estimation may converge only to a local rather than the global minimum. Consequently, these prediction models cannot ensure final asymptotic convergence to the real sample model.

Moreover, actual monitored gearbox systems primarily operate under time-varying working conditions, with the distribution of their sample sequence tending to be unstable. Unlike time-invariant systems, the distribution rules of the degradation process constantly changes with time. Diyin et al.20 described the dynamic condition as a uniform Markov chain and used the Bayesian method to update the signal parameters and residual life distribution of components. Li et al.21 proposed a probabilistic model to estimate the residual life for a degradation process within a specific region under dynamic time-varying operating conditions. Zhou et al.22 transformed the residual life prediction problem into a time-varying trajectory modelling problem and proposed a dynamic control network method to determine the RUL trajectory in a lifetime observation sequence. However, the Bellman equation in the Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) algorithm, an actor-critic reinforcement learning algorithm based on maximum entropy, may affect the prediction. Cao et al.23 developed the time-domain convolution network residual self-attention mechanism, a new deep learning framework to predict the remaining service life of systems under different working conditions.

Long et al.24 proposed a random hybrid system-based method to estimate the RUL based on the complexity and variability of degraded signals under time-varying operating conditions. The RUL under time-varying conditions can be predicted online by modelling the degraded signals and operating conditions of the components; however, the prediction accuracy continuously decreases with an increasing number of working conditions and the amount of calculations required. Furthermore, artificial neural networks require a large amount of high-quality observation data during training, which cannot be easily obtained. The “black box” characteristics of artificial intelligence technology can also reduce the transparency of intelligent learning methods. Additionally, the structure and parameters of neural network models must be formulated beforehand or initialised randomly. These issues cause bottlenecks in prediction performance, hindering artificial intelligence methods from accurately modelling the system mechanism of monitoring equipment.

The kernel density estimation (KDE) method is a data-driven method that makes no assumptions regarding data distribution. It is a non-parametric estimation method that analyses its distribution law based on the data25,26. Xu et al.27 employed KDE for life prediction using real-time degradation characteristic information to determine the prior distribution of parameters in real-time life predictions based on the Bayesian method. Jia et al.28 proposed a new density extrapolation method for efficient reliability analysis. They used KDE and boundary correction to accurately identify the different shapes of target distribution. This method is suitable for calculating the probability density of cylinder failure events under a known number of failure cycles in a cylindrical sample. Zhang et al.29 considered sudden changes in the wear process of a gearbox system and proposed a useful life prediction method based on KDE by detecting the point of sudden change. However, this model assumes that the degradation process remains stable and unchanged.

This study considers the range of issues presented and the time variability of most gearbox systems, and it has the following core components:

-

(1)

A method for predicting the RUL of a system is proposed by determining the degradation distribution from observed data.

-

(2)

Owing to the time variability of the degradation distribution, an RUL prediction model based on time-varying KDE is constructed.

-

(3)

Owing to the impact of the window width h on the estimation accuracy in KDE, an RUL prediction model based on adaptive h and time-varying KDE is constructed.

-

(4)

To avoid unnecessary repeated calculations of KDE when new observation data are added, a recursive update model based on adaptive h and time-varying KDE is constructed.

Time-varying KDE for the incremental distribution of degenerate features

Modelling of time-varying KDE

The incremental distribution of the degenerate features in a time-varying system changes with time. Thus, the concept of time-varying weights was introduced to analyse the effect of time series on the KDE and life prediction accuracy of monitoring systems30. Specifically, the closer the sample points are to the current moment, the better they reflect the running status of the current degenerate system over time. Conversely, the further a sample point is from the current moment, the less it influences the current running state. The time-varying weight factor was introduced based on the conventional KDE model to consider the influence of the time-varying weight. Thus, the time-varying weight KDE at time \(t\) is estimated as

Its corresponding cumulative distribution function is given as

where \(w_{t,i}\) denotes the time-varying weight factor, \(T^{\prime }\) denotes the lifetime of the current monitoring equipment, \(K\) selects the most widely used Gaussian kernel, and \(h\) denotes the window width of the time-varying KDE.

Due to the uneven density distribution of the collected sample data, with the presence of regions of high density and low density, employing a fixed window width in a time-varying KDE model can lead to over-smoothing in high-density areas and under-smoothing in low-density regions. This can adversely affect the accuracy of the time-varying KDE and the prediction of remaining useful life. Therefore, to ensure that the time-varying kernel density estimation is closer to the actual values, by introducing a local window width factor \(\lambda_{i} = \hat{f}(\Delta X_{i} )^{{ - \frac{1}{2}}}\) to dynamically adjust the window size in response to changes in data density, the time-varying weighted KDE model based on an adaptive window width can be expressed as follows:

here \(h_{i}\) denotes the adaptive window width: \(h_{i} = h_{0} \cdot \lambda_{i} = h_{0} \cdot \hat{f}(\Delta X_{i} )^{{ - \frac{1}{2}}}\), where \(h_{0}\) is the initial optimal window width of the sample dataset, obtained by minimising the integral mean squared error between the KDE and the actual density; \(\hat{f}(\Delta X_{i} )\) is the KDE of the initial optimal window width29.

Time-varying weight selection

In the KDE model with time-varying weights, \(w_{t,i}\) denotes a time-varying weighting factor. Assuming that \(w_{t,i}\) decreases exponentially with increasing interval between the sample data \(\Delta X_{i} (i = 1,2, \ldots ,t)\) and the current sample \(\Delta X_{t}\), \(w_{t,i}\) can be defined as

where \(\omega\) denotes the forgetting factor and satisfies \(0 \le \omega < 1\). The interval between \(i\) and \(t\) reflects the interval between \(\Delta x_{i} (i = 1,2,\ldots,t)\) and \(\Delta x_{t}\). The smaller the interval, the larger the time-varying weight (\(w_{t,i}\)), and vice versa. The sum over \(w_{t,i}\), denoted by \(s_{t}\), can be expressed as

Evidently, \(w_{t,i}\) satisfies the sum of its weights when t → ∞.

Model parameter estimation

The current observable moment \(t(t = 1,2, \ldots ,T^{\prime } )\) and current known sample \(\Delta X_{i} (i = 1,2, \ldots ,t)\) obey the respective time-varying KDEs, \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{f}_{i} (\Delta x)(i = 1,2, \ldots ,t)\). The unknown parameter \(\omega\) in the model can be determined through maximum likelihood estimation. Substituting the known sample \(\Delta X_{i} (i = 1,2, \ldots ,t)\) into the time-varying KDE \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{f}_{i} (\Delta x)(i = 1,2, \ldots ,T^{\prime } )\), the likelihood function, \(L(\omega )\), of \(\omega\) can be expressed as

The log-likelihood function \(l(\omega )\), which is normalised according to the sample size, can be expressed as

The derivative of \(l(\omega )\) with respect to \(\omega\) is set equal to 0, as follows:

here the value of \(\omega\) can be obtained using the finite difference method, \(\frac{dl(\omega )}{{d\omega }} = \frac{l(\omega + \Delta \omega ) - l(\omega )}{{\Delta \omega }}\), to maximise the constraint.

Recursive update of time-varying KDE for degenerate feature increment

This study used real-time monitoring equipment wherein the number of samples continuously increased during the real-time operation process. Therefore, the time-varying weight, \(w_{t,i}\), had to be recalculated and reallocated for each additional sample data. The time-varying KDE for known historical samples also had to be recalculated. In the time-varying weight KDE model, the introduction of a weight factor \(w_{t,i}\) enabled the function \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{f}_{t} (\Delta x)\) to be updated efficiently through a recursive formula. This method significantly reduced the amount of redundant computation required for kernel density estimation in continuous monitoring systems, substantially enhanced the computational efficiency of the estimation process, and thus optimised the overall performance and efficiency of the system.

The time-varying weighted KDE \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{f}_{t} (\Delta x)\) at time \(t(t = 1,2, \ldots ,T^{\prime } )\) can be further expressed using Eq. (3) as follows:

The time-varying weighted kernel density estimate \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{f}_{t - 1} (\Delta x)\) at time \(t - 1\) is given as

Accordingly,

Equation (12) shows that the time-varying weighted KDE \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{f}_{t} (\Delta x)\) at time \(t\) can be recursively obtained from \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{f}_{t - 1} (\Delta x)\) at time \(t - 1\). This helps recursively update the time-varying KDE of the degenerate feature increment and reduce the amount of unnecessary repeated calculations when the time-varying weight KDE is solved in the continuous monitoring process.

Prediction of the degradation feature increment

In time-varying systems, the increment in the uncollected degenerate features must first be estimated to accurately predict the remaining life. Owing to the time series of the sample data, it is assumed that the closer a sample data instance is to the current sample, the better it can reflect the running state of the following samples, and vice versa. According to the exponentially weighted moving average method, which is a scheme used to weigh current and past sample data, the weights of sample data instances closer to the current time are larger and decrease as the time interval increases. Owing to its simplicity, this method has been extensively used in practical applications.

By setting \(t\) as the current time, the prediction model of the random time series \(\Delta X_{t}\) at time \(t\) can be expressed as

where \(\varepsilon_{t}\) denotes white noise, which satisfies \(E(\varepsilon_{t} ) = 0\) and \(E(\varepsilon_{t}^{2} ) = \sigma_{\varepsilon }^{2} > 0\); and \(w_{t,i}^{\prime }\) represents the exponential weight coefficient of sample \(\Delta X_{t - i}\), which satisfies

where \(\beta\) represents the decay factor, which satisfies \(0 \le \beta < 1\); when \(i \to \infty\), its weight sum is \(s_{t}^{\prime } = \sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{\infty } {w_{t,i}^{\prime } } = 1\).

Equation (14) can be further expressed as

where \(B\) denotes the backwards operator31.

Moreover,

When \(t \to \infty\),

Therefore,

which can be written as

here,

When \(t \to \infty\), the prediction model of a random time series \(\Delta X_{t}\) becomes equivalent to

When both sides of \(W_{t} = \varepsilon_{t} - \beta \varepsilon_{t - 1}\) are multiplied by \(W_{t}\), the following mathematical expression can be obtained:

By multiplying the two sides of \(W_{t}\) by \(W_{t - 1}\) and calculating the mathematical expectation, we obtain

The correlation coefficient can then be obtained from Eqs. (22) and (23) as follows:

As \(0 \le \beta < 1\), a parameter \(\beta\) can be defined as

In actual monitoring systems, the number of samples collected is often limited. If \(t(t = 1,2,\ldots,T^{\prime})\) represents the current monitored time, the estimated value \(\hat{\beta }\) of \(\beta\) in the exponential weighted moving average model can be obtained from the known sample (\(\Delta X_{1} ,\Delta X_{2} ,\ldots,\Delta X_{t}\)) as follows:

-

(a)

Calculate \(W_{i} = \Delta X_{i} - \Delta X_{i - 1}\) (\(i = 2,3, \ldots ,t\))

-

(b)

Calculate \(\overline{W} = \frac{1}{t - 1}\sum\nolimits_{i = 2}^{t} {W_{i} }\).

-

(c)

Calculate \(\hat{\tau }_{0} = \frac{1}{t - 1}\sum\nolimits_{i = 2}^{t} {(W_{i} - \overline{W})^{2} }\), \(\hat{\tau }_{1} = \frac{1}{t - 2}\sum\nolimits_{i = 2}^{t - 1} {(W_{i} - \overline{W})\left( {(W_{i + 1} - \overline{W})} \right)}\).

The correlation coefficient can then be expressed as

$$\hat{\rho }_{1} = \frac{{\hat{\tau }_{1} }}{{\hat{\tau }_{0} }}$$(26) -

(d)

The estimated value \(\hat{\beta }\) of \(\beta\) is then expressed as

$$\hat{\beta } = \frac{{ - 1 + \sqrt {1 - 4\hat{\rho }_{1}^{2} } }}{{2\hat{\rho }_{1} }}$$(27)

For a finite number of samples at time \(t(t = 1,2, \ldots ,T^{\prime } )\), the prediction model of the time series \(\Delta X_{t}\) can be expressed as

Accordingly, the predicted values of the incremental samples of the degraded features at any time after \(t\) can be obtained by using the time series prediction model of the known samples.

Time-varying KDE of degenerate eigenvalue distribution

Considering the time dependence, the time-varying KDEs change with the addition of degenerate feature increment samples. Assuming that the samples are collected once per unit time, the time-varying KDE can be obtained using the degenerate characteristic incremental samples at the initial time, which is denoted by \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{f}_{1} (\Delta x).\) The time-varying KDE for the degraded feature increment samples at the next time (denoted by \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{f}_{2} (\Delta x))\) can be obtained as the number of continuous monitoring samples increases. The time-varying KDE for the cumulative degradation quantity, \(X_{2} = \Delta X_{1} + \Delta X_{2}\), at time \(t = 2\) (denoted by \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{f}_{2} (x)\)) can be expressed as the convolution of the time-varying KDE (\(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{f}_{1} (\Delta x)\)) of the degraded feature increment and \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{f}_{2} (\Delta x)\), expressed as

Accordingly, the time-varying weighted KDE (denoted by \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{f}_{t} (x)\)) for the characteristic cumulative degradation, \(X_{t} ,t = 1,2, \ldots ,T^{\prime }\), at different times can be obtained as follows:

To reduce unnecessary redundant calculations, Eq. (30) can be expressed recursively as follows:

Essentially, the time-varying weight KDE \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{f}_{t} (x)\) of the characteristic degradation quantity \(X_{t}\) at a different time \(t\) can be obtained through recursion from the time-varying weight KDE of the characteristic degradation quantity \(X_{t - 1}\) at time \(t - 1\).

Real-time residual life prediction model based on time-varying KDE

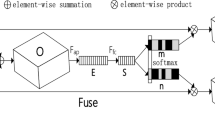

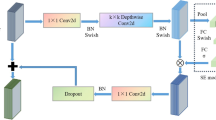

Figure 1 depicts the prediction method flow based on the time-varying KDE.

We set \(t\) as the present monitoring moment and \(x_{th}\) as the failure threshold. When the cumulative feature degradation reaches \(x_{th}\), the system is considered to have failed. Figure 2 depicts the change trend curve of the overall degradation characteristics of the degraded system. Let \(T\) be the RUL of the degenerate system at point \(t\) and \(F_{t} (T)\) be the probability distribution function of the remaining life. \(F_{t} (T)\) can then be expressed as

where \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{f}_{t + T} (x)\) denotes the probability density of the degenerate characteristic \(X_{t + T}\) at time \(t + T\), which can be obtained from the convolution of the time-varying KDE \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{f}_{i} ({\Delta }x),i = 1,2, \ldots ,t + T\), of the characteristic degradation increment at different historical times and can be expressed as

Equation (33) can be expressed recursively as follows:

Essentially, the probability density \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{f}_{t + T} (x)\) of the degenerate characteristic \(X_{t + T}\) at time \(t + T\) can be obtained through the convolution of the probability density \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{f}_{t + T - 1} (x)\) of the characteristic degradation quantity \(X_{t + T - 1}\) at the previous time and the time-varying KDE \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{f}_{t + T} (\Delta x)\) of the characteristic degradation increment prediction value \(\Delta X_{t + T}\) at time \(t + T\).

Substituting Eq. (34) into Eq. (32), the probability density function \(\hat{f}_{t} (T)\) of the RUL, which is estimated based on the time-varying kernel density, can be expressed as follows:

Similarly, the real-time residual life can be predicted at any time after \(t\).

Case analysis

To further verify the applicability of the proposed method, the RUL was predicted based on the data collected during gear fatigue. The data were derived from the test bench presented in Fig. 3, which depicts the positions of the main test gearbox and the accompanying test gearbox. The centre distance between the gearboxes was 15 cm. The monitored data collected during the test included temperature and vibration data. The gears were meshed using staggered teeth, as shown in Fig. 4. Figures 5 and 6 depict the specific installation positions of the vibration and temperature sensors. Table 1 lists the functions of the sensors installed at different positions.

The output torque of the monitored gear was 822.7 N m. Tooth breakage due to continuous gear wear under time-varying working conditions was defined as failure.

The root mean square (RMS) was used to accurately reflect the change in the degradation state during gear wear. By preprocessing the vibration signals received by the sensor (4)32, we extracted the RMS feature of the signal. The signal was sampled at a rate of 25.6 kHz, with a duration of 60 s and a sampling interval of 9 min, resulting in an RMS Monitoring Time (RMS-MT) curve, as shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7 depicts the RMS characteristic curve representing the degradation state of the gear during the process from meshing to failure, and the specific description is presented in Table 2.

Prediction of the degradation feature increment

In a time-varying system, the degradation distribution of the sample series changes with time. Therefore, the degradation feature increment must first be predicted to predict the RUL of the degenerate system. Figure 8 depicts the mean curve of the degradation state obtained by the accumulation of the incremental values of the degradation characteristics estimated using the exponential weighted moving average method when the monitored gear wear test was run for different periods.

Figure 8 depicts the difference between the degradation state prediction curves at different times. The predicted degradation characteristic curve at 70 h significantly deviates from the actual value, indicating a large error in the estimated degradation characteristic increment value. The monitoring information gradually increases with increasing monitoring time, and the degradation state prediction curve becomes closer to the actual degradation curve. Therefore, the error in the estimated degradation feature increment value gradually decreases. The dynamic changes in the gear wear degradation feature can be tracked and monitored effectively based on the estimated value of the degradation feature increment. Furthermore, the degradation feature increment value estimated using the exponential weighted moving average method is closer to the actual degradation feature increment value.

Comparison of residual life prediction results for different window widths

The window width is adaptively selected based on the change in the sample density to improve the accuracy of the estimation of the degraded feature distribution owing to the random change in the sample density of the degraded features during the gear wear test. Essentially, the area with dense samples is estimated using a smaller window width, whereas the area with sparse samples is estimated using a larger window width.

Table 3 presents a comparison of the mean time to failure (MTTF)33 results for fixed and adaptive smoothing window widths with time-varying KDE during the gear wear test for different running times.

A comparison of the data in Table 3 shows that the remaining useful life prediction using the adaptive window width kernel density method is more accurate than the method based on fixed window width kernel density estimation. Additionally, Table 3 also indicates that for datasets of different sizes, the accuracy of remaining useful life prediction using adaptive window width kernel density with large datasets shows a more significant improvement compared to using small datasets.

Figure 9 presents a comparison of the corresponding prediction results. Table 3 and Fig. 9 reveal that with increasing gear running time, the errors between the MTTF values predicted using the two window width methods and the actual remaining life decreased continuously. Furthermore, the MTTF predicted via the window width method used in this study was closer to the true value than that predicted by the fixed window width method, indicating that the uncertainty of the prediction results was reduced.

To demonstrate the advantages of the proposed method more directly, the root mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE) were introduced as measurement standards. Table 4 and Fig. 10 present a comparison of the RMSE and MAE of the remaining lives of various prediction methods. The smaller the standard value, the greater the accuracy of the prediction and the better the performance. The RMSE is expressed as follows:

The MAE is expressed as follows:

where \(i\) represents the monitoring time point and \(\Delta_{i}\) denotes the absolute error between the average remaining life predicted at different and corresponding times.

Time-varying kernel density comparison of the probability density for real-time remaining life estimation

Figure 11 compares the MTTF predicted by the time-varying KDE and the actual RUL for different running times during actual gear operation.

Evidently, at the initial stage of gear wear, the error between the predicted and actual values of the real-time residual life was large owing to the limited number of known degradation samples. As the gear wear test continued, the sample data continued to increase, and the probability density curve of the predicted RUL narrowed, indicating that the variance and the uncertainty of life prediction continued to decrease. The predicted residual life became increasingly close to the actual residual life.

Comparison of time-varying KDE and DGN model-based RUL predictions

To verify the competitiveness of the proposed method, Table 5 and Fig. 12 present the results of two highly rated methods that were evaluated on the same dataset, in addition to the method suggested in the present study.

As SAC in a previous study22 uses the Bellman equation to update the estimates of the state and action value functions, the improper setting of the discount factor in the Bellman equation under time-varying operating conditions results in poor generalisation of the algorithm under time-varying operating conditions. The ensemble model34 in the process of training multiple base models, due to the inability to fully capture certain unique features in the data, coupled with the risk of overfitting in the process of model selection and parameter tuning, leads to unsatisfactory prediction effects of the ensemble model. The data shown in Table 5 and Fig. 12 indicate that although the method proposed in this study is not complex in theory, it still maintains a high level of accuracy, thus fully demonstrating the practical application effect and reliability of this method.

To thoroughly evaluate the predictive performance of our proposed method and compare it with two highly regarded methods, we conducted analyses using RMSE (Root Mean Square Error) and MAE (Mean Absolute Error). Tables 6 and Fig. 13 provide a detailed presentation of this comparison.

By contrasting the prediction errors of the three methods, we observed that our proposed method surpasses the DGN time-varying trajectory method and the integrated model in terms of prediction accuracy. Furthermore, the error observed between our proposed method and the actual values was significantly smaller, confirming its higher prediction accuracy and reliability.

Conclusion

In this study, different influence weights were assigned to samples at different times during KDE, and a remaining life prediction method based on time-varying weight KDE was proposed while considering the time variability of gearbox systems and time seriality of the sample data.

Because the system distribution changes with time, a time-varying weight was introduced in the proposed model based on the different impacts of the time series samples collected at different instances on the distribution in the time-varying system. The closer the samples were to the current time, the greater the influence on the distribution and the larger the weight to be assigned, and vice versa.

For samples that were not collected during continuous monitoring, the exponential weighted moving average method was employed to make predictions based on the past and current sample data. Additionally, as the proposed model was repeatedly implemented when the sample data continuously increased during the operation of the gearbox system, a real-time update model was established to effectively improve the computational efficiency. Finally, the rationality and competitiveness of the proposed model were verified through a gear wear test.

Owing to advancements in the manufacturing industry, single-component systems are no longer effective for mechanical equipment, and the interdependence between multiple components cannot be ignored. Therefore, in future works, we aim to analyse the prediction and health management of multi-component systems from the perspective of random correlations among gearbox system components.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript file.

References

Mishra, R. K. et al. A generalized method for diagnosing multi-faults in rotating machines using imbalance datasets of different sensor modalities. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 132, 107973 (2024).

Mishra, R. K. et al. An intelligent bearing fault diagnosis based on hybrid signal processing and Henry gas solubility optimization. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 236(19), 10378–10391 (2022).

Wang, J., Xu, C., Zhang, J. & Zhong, R. Big data analytics for intelligent manufacturing systems: A review. J. Manuf. Syst. 62, 738–752 (2022).

Wang, H., Ma, X. & Zhao, Y. An improved Wiener process model with adaptive drift and diffusion for online remaining useful life prediction. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 127, 370–387 (2019).

Sawant, V., Deshmukh, R. & Awati, C. Machine learning techniques for prediction of capacitance and remaining useful life of supercapacitors: A comprehensive review. J. Energy Chem. 77, 439–451 (2022).

Ferreira, C. & Gonçalves, G. Remaining useful life prediction and challenges: A literature review on the use of machine learning methods. J. Manuf. Syst. 63, 550–562 (2022).

Ansari, S., Ayob, A., Lipu, M. S. H., Hussain, A. & Saad, M. H. M. Remaining useful life prediction for lithium-ion battery storage system: A comprehensive review of methods, key factors, issues and future outlook. Energy Rep. 8, 12153–12185 (2022).

Ren, L., Liu, Y., Wang, X., Lu, J. & Deen, M. J. Cloud–edge-based lightweight temporal convolutional networks for remaining useful life prediction in IIoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 8(16), 12578–12587 (2020).

Chen, C. et al. Predictive maintenance using cox proportional hazard deep learning. Adv. Eng. Inform. 44, 101054 (2020).

Liu, B., Teng, Y. & Huang, Q. RETRACTED: A novel imprecise reliability prediction method for incomplete lifetime data based on two-parameter Weibull distribution. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part O J. Risk Reliab. 234(1), 208–218 (2020).

Cheng, Y., Hu, K., Wu, J., Zhu, H. & Shao, X. A convolutional neural network based degradation indicator construction and health prognosis using bidirectional long short-term memory network for rolling bearings. Adv. Eng. Inform. 48, 101247 (2021).

Yan, M., Wang, X., Wang, B., Chang, M. & Muhammad, I. Bearing remaining useful life prediction using support vector machine and hybrid degradation tracking model. ISA Trans. 98, 471–482 (2020).

Yang, T., Zheng, Z. & Qi, L. A method for degradation prediction based on Hidden semi-Markov models with mixture of Kernels. J. Comput. Ind. 122, 103295 (2020).

Hu, Y., Miao, X., Si, Y., Pan, E. & Zio, E. Prognostics and health management: A review from the perspectives of design, development and decision. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 217, 108063 (2022).

Changhua, H., Fan, H. & Wang, Z. Gamma process-based degradation modeling and residual life prediction. In Residual Life Prediction and Optimal Maintenance Decision for a Piece of Equipment (eds Changhua, H. et al.) 77–97 (Springer, 2022).

Wang, Y. F., Huang, Y. & Liao, W. C. Degradation analysis on trend gamma process. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 38(2), 941–956 (2022).

Song, K. & Cui, L. A common random effect induced bivariate gamma degradation process with application to remaining useful life prediction. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 219, 108200 (2022).

Li, H., Zhang, Z., Li, T. & Si, X. A review on physics-informed data-driven remaining useful life prediction: Challenges and opportunities. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 209, 111120 (2024).

Ghadami, A. & Epureanu, B. I. Data-driven prediction in dynamical systems: Recent developments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 380(2229), 20210213 (2022).

Diyin, T., Jinrong, C. A. O. & Jinsong, Y. U. Remaining useful life prediction for engineering systems under dynamic operational conditions: A semi-Markov decision process-based approach. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 32(3), 627–638 (2019).

Li, S. et al. Field degradation modeling and prognostics under time-varying operating conditions: A Bayesian based filtering algorithm. Appl. Math. Model. 99, 435–457 (2021).

Zhou, Z. et al. Time-varying trajectory modeling via dynamic governing network for remaining useful life prediction. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 182, 109610 (2023).

Cao, Y., Ding, Y., Jia, M. & Tian, R. A novel temporal convolutional network with residual self-attention mechanism for remaining useful life prediction of rolling bearings. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 215, 107813 (2021).

Long, J., Chen, C., Liu, Z., Guo, J. & Chen, W. Stochastic hybrid system approach to task-orientated remaining useful life prediction under time-varying operating conditions. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 225, 108568 (2022).

Zhang, K. et al. Wind power interval prediction based on hybrid semi-cloud model and nonparametric kernel density estimation. Energy Rep. 8, 1068–1078 (2022).

Wang, S., Li, A., Wen, K. & Wu, X. Robust kernels for kernel density estimation. Econ. Lett. 191, 109138 (2020).

Xu, J., Lu, C. & Liu, H. M. Real-time life prediction for rolling bearings based on nonparametric Bayesian updating method. Appl. Mech. Mater. 764, 431–436 (2015).

Jia, G., Tabandeh, A. & Gardoni, P. A density extrapolation approach to estimate failure probabilities. Struct. Saf. 93, 102128 (2021).

Zhang, W., Shi, H., Zeng, J. & Zhang, Y. Real-time residual life prediction based on kernel density estimation considering abrupt change point detection. Meas. Sci. Technol. 31(11), 115108 (2020).

Harvey, A. & Oryshchenko, V. Kernel density estimation for time series data. Int. J. Forecast. 28(1), 3–14 (2012).

Qiu, R. Research on parameters of EWMA model. J. Nanjing Univ. Posts Telecommun. 9(4), 102–105 (1989).

Li, L., Zhou, H., Liu, H., Zhang, C. & Liu, J. A hybrid method coupling empirical mode decomposition and a long short-term memory network to predict missing measured signal data of SHM systems. J. Struct. Health Monit. 20(4), 1778–1793 (2021).

Ebeling, C. E. An Introduction to Reliability and Maintainability Engineering (Waveland Press, 2019).

Rezazadeh, N. et al. Ensemble learning for estimating remaining useful life: Incorporating linear, KNN, and Gaussian process regression. In International Workshop on Autonomous Remanufacturing 201–212 (Springer Nature, 2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Key Research and Development projects in Shanxi Province (No. 202202100401002); Shanxi Scholarship Council of China (No. 2021-135); Fund Program for the Scientific Activities of Selected Returned Overseas Professionals in Shanxi Province (No. 20220029); Natural Science Foundation of Shanxi Province (No. 202203021222214); Scientific and Technological Innovation Programs of Higher Education Institutions in Shanxi (2022L306); and PhD Program of Taiyuan University of Science and Technology (No. 20222044).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Weizhen Zhang, Jianchao Zeng, and Hui Shi wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, W., Zeng, J., Shi, H. et al. Time-weighted kernel density for gearbox residual life prediction. Sci Rep 15, 10130 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94924-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94924-z