Abstract

This study aims to evaluate the effects of a creative expressive art-based storytelling accompanied by caregivers (CrEAS-AC) program on reducing behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in older adults with dementia and caregiver burden compared to a general social contact (SC) control group. In this two-arm randomized controlled trial, dyads comprising participants with dementia and their caregivers were randomly assigned to the CrEAS-AC (n = 39) and SC groups (n = 39). Interventions were applied twice per week for 12 weeks. The primary outcomes were BPSD (NPI and AES-I) and caregiver distress, while secondary outcomes included communication ability (SFACS-S and SFACS-C), caregiver burden (CBI), and other health-related outcomes (activities of daily living and QOL-AD). All variables were measured at baseline, 12-week follow-up, and 24-week follow-up. Linear mixed model analyses indicated that participants in the CrEAS-AC group showed significantly lower scores on NPI, AES-I, caregiver distress, and CBI post-intervention at the 12-week follow-up, compared with the SC group. They also showed higher scores on QOL-AD, SFACS-S, and SFACS-C. Baseline characteristics did not modify the effects of the interventions, which were maintained until at least 24-week follow-up. The CrEAS-AC program, as an art-based intervention, is therefore potentially effective in reducing behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia and improving communication ability and quality of life in older adults with dementia, as well as reducing caregivers’ distress and burden.

Trial registration: The study was registered in the Chinese Clinical Trials Registry (ID: ChiCTR2200064838) on 19/10/2022.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dementia is the greatest global challenge for health and social care in the 21st century1. It is a leading cause of disability and dependency worldwide, mainly affecting older people1,2. In 2019, Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia ranked as the 7th leading cause of death globally3. Currently, more than 55 million people have dementia worldwide, with China accounting for approximately 25% of the global dementia population4,5. As a populous country, China has a large aging population, with 191 million people aged 65 years and older, making up 13.50% of the country’s population6. A multicenter, large sample cross-sectional study showed that the overall prevalence of dementia in China is 6%7. With the continued aging of the population, China now has the largest population of patients with dementia in the world, placing a heavy burden on the public and health care systems5. The global cost of dementia was estimated at $1.3 trillion in 2019, and is projected to reach $2.8 trillion by 20304. Furthermore, the socioeconomic burden of dementia in China exceeds the global average, accounting for 1.47% of the country’s gross domestic product, imposing a huge economic burden on society5.

The problems facing older adults with dementia are complex because they exhibit symptoms in many domains1. The two core symptoms of dementia are cognitive impairment and neuropsychiatric behaviors, which are common and often considered to be the greatest challenge in dementia care1,4,8,9,10. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD)—also known as neuropsychiatric behaviors—include apathy, agitation, aberrant motor behavior, anxiety, elation, irritability, hallucinations, depression, disinhibition, delusions, and sleep or appetite problems11. BPSD are common in people with dementia—it is estimated that over 97% of all patients with dementia are affected by BPSD during their illness, with apathy being the commonest symptom12,13. BPSD often lead to increased healthcare costs and caregiver burden11. The emergence and worsening of BPSD not only affect the quality of life of patients and increase their their likelihood of poor outcomes, but also necessitate long-term care by family members owing to the long-term and irreversible nature of dementia. Dementia also imposes a huge caregiving burden on families and caregivers, thus predisposing caregivers to a series of health problems, such as anxiety, depression, sleep abnormalities, and chronic illnesses14. Under COVID-19 preventive and control measures, daily social and outdoor activities of patients with dementia were interrupted, resulting in their increased social isolation of older adults with dementia, deterioration of their cognitive abilities, and a series of BPSD, which further aggravated the burden on caregivers15. The Need-Driven Dementia-Compromised Behavior (NDB) theory16 suggests that abnormal behavioral symptoms in individuals with dementia arise from the outward expression of their unmet intrinsic needs. Fulfilling these physical and psychological needs in a timely manner can significantly reduce the occurrence of such behaviors. Intervening during the moderate and early stages of dementia is crucial1. Unlike pharmacological treatments, non-pharmacological interventions—recommended as a first-line treatment—have demonstrated effectiveness in improving the quality of life and slowing disease progression in patients with dementia. Additionally, these interventions have shown proven safety and rationality17,18.

Art therapy is by the British Association of Art Therapists defined as a form of psychotherapy that uses art media as a means of self-expression and communication19. Art-based interventions include various forms of arts such as visual arts, dance or movement, drama, storytelling, and music20,21. Among them, visual arts take various forms including painting, drawing, clay modeling, and collage22. Art-based interventions are generally considered a measure for managing dementia manifestations as they may help to reduce BPSD as well as improve cognitive function and quality of life with minimal side effects23. Several studies have shown that art-based interventions are beneficial for communication, meeting the emotional and psychological needs of patients with dementia, maintaining skills, improving well-being and self-esteem, as well as reducing caregiver burden24,25,26. The Creative Expressive Arts-based Storytelling (CrEAS) therapy27 is designed to enhance the neuropsychological well-being of individuals with cognitive disabilities. It achieves this by providing dual-channel creative expression opportunities through both nonverbal visual tasks—such as drawing and collage—and verbal storytelling activities. The CrEAS intervention focuses on processes that promote complex coordination between brain regions during artistic engagement and storytelling, thereby stimulating various cognitive domains. This approach not only provides sensory stimulation and facilitates self-expression but also fosters social interaction and offers emotional relief for patients with cognitive impairments27,28. By addressing these multifaceted needs, CrEAS aims to alleviate BPSD in cognitively impaired individuals.

Although many studies have explored the impact of CrEAS interventions on individuals with dementia, certain limitations still exist in previous research. These include a lack of rigorous experimental design in research, differences in participant characteristics, variability in outcome measurement, and inconsistencies in the duration and quality of interventions. However, there has been limited investigation into the impact of these intervention on caregivers23,24. The evidence regarding the effectiveness of CrEAS interventions for patients with dementia remains inconclusive23. Therefore, high-quality randomized controlled trials are needed to verify the impact of CrEAS interventions on patients with dementia and their caregivers.

To address these gaps, we have designed a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effects of the Creative Expressive Arts-based Storytelling Accompanied by Caregivers (CrEAS-AC) program in individuals with mild-to-moderate dementia and their caregivers. The study aims to assess the impact of the CrEAS-AC program on BPSD, communication ability, quality of life, cognitive function, and caregiver burden, compared to a general Social Contact (SC) control group.

Methods

Study design

The present study was a prospective, single-blind randomized controlled trial that included two parallel groups in a 1:1 allocation ratio. It was conducted in conducted on older adults with mild-to-moderate dementia and their caregivers. Information related to study design, protocol, and sample size can be found on the website (https://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.html?proj=180424). All participant variables were evaluated at baseline (T0), 12-week follow-up (T1), and 24-week follow-up (T2). This study adhered to CONSORT guidelines.

Participants

Participants were recruited from five geriatric wards within a tertiary care hospital in Fuzhou City, China, which has a total of 248 beds. These wards serve a significant number of older adults with disabilities or dementia, and hospital stays lasting more than three months are not uncommon. To ensure the smooth and safe execution of intervention activities, we included the primary informal caregivers of these older adults in the study. Eligibility was determined based on predefined inclusion criteria. We promoted the study through multiple channels, including posters, face-to-face presentations to patients and their informal caregivers, and peer referrals. Potential participants were approached by research staff who provided comprehensive information about the study and obtained informed consent. Due to the challenges posed by the COVID-19 outbreak, recruitment was extended. We were compelled to temporarily suspend recruitment during the peak of the outbreak and only resumed once the situation had stabilized. All data were collected between October 2022 and September 2023.

Inclusion criteria

Eligible participants met the following criteria

Older adults with dementia: (i) age ≥ 65 years and met the diagnostic criteria for dementia in the WHO International Classification of Diseases ICD-1029; (ii) Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale scores of 1 or 2; (iii) medication and stabilization of the condition in the last month; (iv) have a certain level of hearing and vision, and retain a certain level of hand function, and able to participate in the activity; (v) older adults or their proxy signed a written informed consent form.

Informal caregivers: (i) taking care of the patients as the primary caregivers for ≥ 30 days and ≥ 8 h per day; (ii) Expected to continue caring for 3 months or more; (iii) Having the ability to read, understand, and communicate normally, and cooperate in activities; (iv) provision of informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria were as follows

Older adults with dementia were excluded from the study if they met any of the following criteria: (i) other types of mental disorders; (ii) dementia caused by diseases related to the central nervous system (e.g., encephalitis, brain tumors, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, and Parkinson’s disease); (iii) dementia caused by nutritional and metabolic disorders(e.g., abnormalities in thyroid function, vitamin B12 or folic acid deficiency, and persistent hypoglycemia); (iv) drug or alcohol dependency; (v) participation in another clinical research during the study; (vi) missed one-third or more of the total number of intervention activities; (vii) severe physical or mental disorders, extreme weakness, or other conditions preventing participation; (viii) unwillingness to continue participating.

Informal caregivers were excluded from the study if they met any of the following criteria: (i) serious physical disability (e.g., malignant tumors, heart failure, severe liver or kidney disease) or psychiatric disorder; (ii) no longer caring for the patient with dementia; (iii) unwillingness to continue participating.

Sample size

The required sample size was estimated based on a completely random design for comparing the means of two independent samples. Referring to relevant studies30, the apathy scores for BPSD were 1.76 ± 2.01 in the intervention group and 3.35 ± 3.05 in the control group. Using the sample size calculation formula for comparing the means of two groups in a randomized controlled trial, \(\:{\text{n}}_{1}={\text{n}}_{2}\)= \(\:\frac{{({Z}_{\alpha\:}+{Z}_{\beta\:})}^{2}\times\:2{\sigma\:}^{2}}{{\delta\:}^{2}}\), a sample size of 33 participants per group was determined to be sufficient to detect an effect with a type I error rate of 5% (α = 0.05) and 90% power (β = 0.10). Taking into consideration a 15% attrition rate, a total of 78 participants will be needed, with 39 participants per group.

Randomization, blinding, and allocation concealment

Participants who met the specified inclusion and exclusion criteria were randomly assigned to the CrEAS-AC group or a general SC control group in a 1:1 ratio after obtaining written informed consent and baseline assessment using a random number table method. Ensuring allocation concealment, we put 78 random numbers into sealed, opaque envelopes and arranged them in order of numbering. Randomized grouping was completed by staff who did not participate in the recruitment and outcome assessment. Owing to the inherent nature of non-pharmacological interventions, it was not possible to blind participants or CrEAS-AC program staff in this study. However, to minimize bias, the researchers and statisticians involved in data collection were blinded.

Intervention

All implementing staff were formally trained geriatric nurses with bachelor’s degrees. The CrEAS-AC program was developed based on a previous study by our research team31,32,33, focus group interview, and literature review, and the final intervention plan was revised through an expert meeting. The CrEAS-AC program is based on the Expressive Therapy Continuum34 as a theoretical framework and combined with storytelling (TimeSlips) to form a systematic and standardized intervention paradigm. The main part of the CrEAS-AC program activity process includes 5 min of introduction, 5–10 min of warm-up interaction games, 20–30 min of art making, and 20–30 min of TimeSlips. Two implementing staff were involved in each activity, one to lead the activity and the other to assist and observe. For safety and creative efficiency, the older adults participated in activities, accompanied by their caregivers, which required the older adults’ caregivers to sit next to them to assist them. Participants create art in three progressive stages, with four different creative themes. A full description of the CrEAS-AC program has been published35. The activity took place in the activity center of the geriatric wards. A brief description of the CrEAS-AC intervention can be found in (Supplemental Table 1). Supplemental Table 2 shows the schedule for 24 art-making lessons. The CrEAS-AC intervention process and the finished art-making works can be found in the supplementary materials (Appendix 1–2).

To rule out improvements in outcome indicators due to excessive attention to participants, the control group engaged in general social contact activities. In order to ensure equal attention to the CrEAS-AC and SC control groups, the number, frequency, maintenance and intervals of participation in the intervention activities should be the same for both groups, with specific caregivers participating in each group without interference. The frequency of activities for both groups was twice per week for 12 weeks—totaling 24 activities. The SC activity process of the control group is shown in (Supplemental Table 3), and the schedule of 24 SC activities is shown in (Supplemental Table 4). Older adults in both groups were provided with routine geriatric care, dementia health education.

Data collection

Outcome measures were scheduled at times convenient for the participants to minimize disruption and ensure their comfort. Trained investigators conducted face-to-face interviews using a blinded data collection method to reduce bias. Information was gathered from both patients and their informal caregivers or surrogates. Initially, trained investigators interviewed the caregiver to collect relevant background and baseline information. Following this, individuals with dementia were interviewed while their caregivers completed self-reported outcome measures independently. Assessments were conducted at three key time points: baseline (T0), post-intervention (T1), and 3-month follow-up (T2).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was BPSD in the older adults, assessed using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI)36,37, and among them, apathy was measured by the Apathy Evaluation Scale-Informant (AES-I)38,39. NPI assessed the severity and level of distress of 12 neuropsychiatric symptoms (apathy, delusions, hallucinations, dysphoria, anxiety, agitation, irritability, euphoria, disinhibition, aberrant motor behavior, night-time behavior disturbances, and appetite and eating abnormalities) and caregiver distress. The scale total is the sum of the symptom scores for each entry, with higher scores indicating more severe neuropsychiatric symptoms. Caregiver distress is the degree of distress that the symptom causes to the caregiver: the higher the score, the more distress the symptom causes to the caregiver. The NPI scale was assessed by the older adults’ caregivers. AES-I was used to measure the severity of apathy symptoms in patients; higher scores suggest more severe symptoms of apathy. The test-retest reliability of the AES-I scale is 0.76, and Cronbach’s α coefficient is 0.81.

The secondary outcomes were communication skills (SFACS)40,41, quality of life (quality of life-Alzheimer’s disease, QOL-AD)42, Caregiver burden (Caregiver Burden Inventory, CBI)43, and activities of daily living (activities of daily living, ADL)44. The SFACS includes the dimensions of social communication (SFACS-S) and communication of basic needs (SFACS-C). We recorded all adverse events and reasons for withdrawal from the intervention.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Data analysis followed the principles of intention-to-treat to prevent selection bias. The normality test of data distribution was validated using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov. After approaching the normality of each variable, two-sample independent t-tests, x2 tests (or Fisher exact test), or nonparametric tests were used as appropriate to compare the normally distributed variables between the CrEAS-AC intervention group and SC control group. The difference was statistically significant at P < 0.05 for a two-sided test.

Linear mixed-effects regression models were used to assess whether changes in outcome indicators differed significantly over time. Models included the randomization group with time as fixed effects and time × group as interaction effect to account for the correlation between repeated observations for each participant. Estimated marginal means of 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for each time point for both groups. Within-group differences were obtained by pairwise comparisons, allowing us to detect differences between the two groups over time. This result represents the difference in slope and measures the effectiveness of the intervention. Between-group differences were assessed by the estimates of the interaction term time × group with T0 as the reference time. Because covariates were balanced at baseline, they were not included in the covariates calculation. Bonferroni correction was used for multiple comparisons. Adjustments were made for baseline characteristics (such as dementia type, age, sex, and education level) by individually adding these variables to the model. Cohen’s d was used to measure the effect size for the difference in change across time between the two groups. To explore the impact of baseline characteristics on the size of intervention effects, subgroup analysis was conducted by testing the interaction between subgroups and intervention effects. Subgroup analyses were predetermined for the two primary outcome indicators of NPI and caregiver distress. Six predefined subgroup analyses were performed on baseline characteristics including age, sex, education, monthly pension income, dementia type, and chronic disease. The main results of the subgroup analyses were the p values of the coefficients for the group × time × characteristic interactions, as well as the estimation of differences between the CrEAS-AC intervention group and SC control group (95%CI) within each subgroup.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fujian Provincial Hospital (K2022-06-013) and registered in the Chinese Clinical Trials Registry (https://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.html?proj=180424) under the trial registration number ChiCTR2200064838, dated 19 October 2022. All procedures conducted during the trial will adhere to the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, including older adults with dementia, their caregivers, and implementing staff. Written informed consent was collected through face-to-face interviews. Recognizing the potential for impaired decision-making capacity among individuals with dementia, we employed a thorough informed consent process to ensure that all patients or their legally authorized representatives fully understood the study’s purpose, procedures, risks, and benefits. Each patient underwent a capacity assessment conducted by a trained clinician to evaluate their ability to comprehend the study information and make an informed decision regarding participation. For patients deemed unable to provide informed consent due to cognitive impairment, a legally authorized representative, typically a family member or legal guardian, was identified to give proxy consent on their behalf. Even when proxy consent was obtained, efforts were made to involve the participant as much as possible in the decision-making process.

Results

Participants

A total of 147 participant pairs were screened (older adults and their primary caregivers), and 78 were randomly allocated to the CrEAS-AC intervention group (n = 39) or SC control group (n = 39). After the intervention period, 71 participant pairs (91.03%) completed the assessment. The dropout rate was 10.26% in the CrEAS-AC intervention group and 7.69% in the SC control group. At 24 weeks post-intervention, 63 participant pairs (80.77%) completed the follow-up assessment (Fig. 1). The main reasons for attrition were medical reasons, discharge/transfer, and refusal to continue. None of the participants experienced adverse effects during the intervention.

The two groups were well balanced in terms of baseline characteristics. The mean age of older participants was 85.29 years (standard deviation [SD]: 7.11), and the mean age of their caregivers was 52.86 years (SD: 4.79). Baseline characteristics of participants are presented in (Table 1).

Primary outcome

Changes in the primary outcome NPI, caregiver distress, and AES-I in the CrEAS-AC group and SC control group at the 12-week (T1) and 24-week follow-up (T2) are shown in (Fig. 2; Table 2). In a linear mixed model for NPI, caregiver distress, and AES-I scores over time, the time × group interaction effect was found to be significant (P < 0.001) (Table 3). In the CrEAS-AC group, there was a significant reduction in mean difference scores for NPI (− 4.54; P < 0.001), caregiver distress (− 2.85; P < 0.001), and AES-I (− 3.33; P < 0.001) at T1 compared with at T0; there was an increase in mean difference scores for NPI (2.21; P < 0.001), caregiver distress (1.74; P < 0.001), and AES-I (1.31; P < 0.001) when comparing T2 to T1, and a decrease in each primary outcome score when comparing T2 to T0 (P < 0.001) (Table 2). In the SC control group, there was a significant reduction in mean difference scores for caregiver distress (− 0.67; P = 0.014) and AES-I (−1.44; P < 0.001) at T1 compared with that at T0, and there was an increase in mean difference scores for NPI (0.44; P = 0.048) and AES-I (0.92; P < 0.001), but there only AES-I score was still a decrease when comparing T2 to T0 (P = 0.021) (Table 2).

With T0 as the reference time point, the effect of the intervention was measured by the between-group difference in the estimated mean scores of the primary outcome for the two groups at T1. The between-group difference for NPI (− 3.87; P < 0.001), caregiver distress (− 2.18; P < 0.001), and AES-I (− 1.90; P < 0.001) were statistically significant at T1, and were also at T2 (NPI [− 2.10; P < 0.001], caregiver distress [− 0.97; P = 0.019], AES-I [− 1.53; P < 0.001]) (Table 2). Compared to T0, at T1, caregiver distress (Cohen’s d = − 0.66) and AES-I (Cohen’s d = − 0.67) showed moderate effect sizes, while the NPI (Cohen’s d = − 0.92) demonstrated a large effect size. When comparing T2 to T0, the effect sizes for all three variables decreased compared to T1 versus T0. However, the NPI (Cohen’s d = − 0.57) and AES-I (Cohen’s d = − 0.56) still exhibited moderate effect sizes (Table 3).

Secondary outcomes

At the completion of the intervention (T1), notable differences were observed between the CrEAS-AC and SC control groups in communication skills (SFACS-S, SFACS-C), quality of life (QOL-AD), and caregiver burden (CBI). These differences remained considerable at the 24-week follow-up (T2) (Table 2). A linear mixed model analysis of SFACS-S, SFACS-C, QOL-AD, and CBI scores over time revealed a significant time-by-group interaction effect (P < 0.001) (Table 3). This result suggests that the patterns of change in these outcome measures over time were markedly different between the CrEAS-AC group and the SC control group.

In the CrEAS-AC group, analyses by pairwise comparisons indicated statistically significantly improvements over time in SFACS-S, SFACS-C, QOL-AD, and CBI (P < 0.05). In the SC control group, there was a major difference in QOL-AD and CBI at T1 vs. T0 (P < 0.05), ADL at T2 vs. T0 (P < 0.05), SFACS-S, QOL-AD, ADL, and CBI at T2 vs. T1 (P < 0.05).

No serious adverse events related to the intervention were reported. The CrEAS-AC program attendance rate was 94.87%, of which a total of 21 pairs participated in the 24 activities in full, with a withdrawal rate of 10.26%.

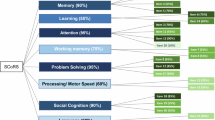

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses showed that baseline characteristics (age, sex, education, monthly pension income, dementia type, and chronic disease) did not modify the effects for the CrEAS-AC intervention group or the SC control group (P for interaction > 0.05; Fig. 3).

Discussion

This two-arm randomized controlled trial demonstrated that the CrEAS-AC program had a positive impact on BPSD, communication skills, quality of life, caregiver distress and burden in older adults with mild-to-moderate dementia, and that these effects were maintained until at least the 24-week follow-up. Although the SC control group also experienced a positive impact in terms of these outcomes as well, it was less strong than in the CrEAS-AC group. This is consistent with the results of similar previous studies and a systematic review24,31,33. Subgroup analyses of primary outcomes at 12 weeks of intervention showed that NPI and caregiver distress were not affected by differences in baseline characteristics, further validating the reliability of the intervention effect.

Hsiao45 conducted a three-armed randomized controlled trial including art therapy, reminiscence therapy, and a comparison group with 54 older adults with dementia. The results showed that art therapy conducted for 50 min per week for 12 weeks positively affected agitated behavior symptoms associated with dementia in older adults with sustained effects. The CrEAS-AC program can alleviate BPSD and improve communication skills in adults with dementia, offering a feasible non-pharmacological intervention for dementia and BPSD. This may be related to several factors. The CrEAS-AC activity includes nonverbal intervention methods for visual arts such as painting, clay, pasting, and rubbings, as well as language stimulation methods such as describing works and storytelling, which can attract the attention of participants, unleash their creative potential, and create a sense of achievement and self-esteem. Group activities can easily mobilize the enthusiasm of participants to participate and better promote individual communication and emotional regulation; further, the mutual influence of peers in group activities cannot be ignored. In this study, the relaxed and soothing environment and the positive guidance of the facilitator created a supportive environment conducive to patient communication and expression, and at the same time helped participants to vent their negative emotions. During the activity, the activity leader used various techniques such as “praise,” “affirmation,” “transference,” and “listening” to guide participants, which had a positive effect on patients. This study proved that this triadic activity approach—in which the nurse guides, the caregiver assists, and the patient is fully engaged in creating the activity—is conducive to the development of the activity and effective communication among the three parties, which makes it easy to achieve the common goal, and also facilitates the maintenance of the relationship between the two parties, ensuring the sustainability of the activity. The prevention and control measures for COVID-19 aggravated BPSD of older adults with dementia15,46, and CrEAS-AC activities provided a platform for the older adults to stimulate cognition, express themselves, and avoid social isolation. The SC control group also showed BPSD amelioration, which may also be related to this effect. Further, 97.43% of the older adults with mild-to-moderate dementia included have one or more BPSD, which is similar to the study of Vik-Mo13.

The CrEAS-AC program improved individuals’ quality of life but had no effect on activities of daily living. Regarding the effect of art-based activities on quality of life, the results of several studies were similar to the present study31,47. However, there were also inconsistent findings. The the findings of D’Cunha48 and Lin33 indicated that creative storytelling therapy did not have an effect on the quality of life of patients with dementia. The reason for these inconsistent findings may be that the QOL-AD is a subjective assessment of the individual’s recent quality of life, and the results are susceptible to fluctuations in mood, sleep, self-perception, and events encountered. The improvement in the quality of life older adults with dementia in this study may be due to the fact that activities can expose them to learning new things, promote socialization, increase the opportunity to communicate with others, make the body and mind happy, and bring a sense of value, achievement, and satisfaction, which have a positive impact on the improvement of the quality of life. A nurse-led staged integral art-based cognitive intervention reported by Yan49 had similarly improved quality-of-life outcomes for cognitively impaired older adults. Art-based intervention studies conducted for older adults with mild-to-moderate dementia are less likely to use the ability to perform ADL as an outcome indicator for assessment, possibly because ADL in older adults with dementia are more severely impaired, and it is difficult to effectively change them in the short term or the degree of change is insufficient to be monitored. The baseline data of the older adults included in this study showed advanced age, long duration of disease, and severe impairment of the ability to perform activities of daily living, and a 3-month intervention cycle may not be sufficient to produce significant changes. In the future, we may seek a more sensitive test applicable to patients with dementia to assess the patient’s ability to perform ADL, or we may extend the intervention cycle for long-term observation of the ability to perform ADL.

Most research on art-based interventions for individuals with dementia focuses on the impact on the person with dementia, while the impact on their caregivers is less known. Vigliotti47 showed that the TimeSlips creative storytelling program improves patient-caregiver interactions but did not analyze caregiver distress and burden. The results of the present study showed that the CrEAS-AC program reduces caregiver distress and caregiver burden. The CrEAS-AC program may improve BPSD and quality of life among older adults with dementia, and the smooth communication and good emotional state between caregivers and older adults can also reduce the caregiver’s distress and burden. Reduced caregiver burden also enables caregivers to take better care of older adults with dementia, which has a beneficial effect on the latter.

The CrEAS-AC program attendance rate was over 90%, with good compliance. There were no adverse events reported in any of the 24 activities, indicating their safety, which was conducive to the participants’ continued participation in the CrEAS-AC program. The main reasons for the older adults’ and their caregivers’ continued participation in the CrEAS-AC program are as follows. Innovative expression in the form of new and interesting activities—each time, a different activity theme and materials can continue to maintain a sense of freshness, so that the participants are still looking forward to the next activity. Activities can be closer to the preferences of older adults and their caregivers to improve the relationship between the two, and they feel the fun and benefit from the activities. The CrEAS-AC activities were conducted in the geriatric ward, the participants have a high level of trust in this kind of activities organized and guided by nurses, and are happy to participate and cooperate, which ensures the continuation of the activities. Participants were rewarded with their own finished work and a gift at each stage.

The need-driven model suggests that BPSD arise from unmet needs, which can be physical, emotional, social, or environmental. The CrEAS-AC intervention is designed to address these unmet needs through various mechanisms: artistic activities like drawing and collage provide rich sensory experiences, engaging multiple senses and alleviating boredom or restlessness, which in turn reduces agitation and improves overall well-being; the intervention offers a platform for emotional expression through both visual and verbal channels, allowing participants to articulate their feelings and experiences by creating art and sharing stories, fostering a sense of validation and emotional relief; encouraging interaction among participants and facilitators within a group setting combats loneliness and isolation, promoting a sense of community and belonging and enhancing social engagement; the inclusion of both nonverbal and verbal tasks stimulates various cognitive domains, helping to maintain cognitive abilities and slow cognitive decline; and creating a supportive and creative environment mitigates the negative effects of institutional settings, with a positive atmosphere enhancing participants’ comfort and willingness to engage in activities. By addressing these various needs, the CrEAS-AC intervention seeks to alleviate BPSD symptoms and enhance quality of life. The intervention’s design is closely aligned with the principles of the need-driven model, ensuring that it targets the root causes of distress and promotes participants’ overall well-being.

Implications and limitations

This study’s art-based form of intervention, including its theoretical framework, process, and content, has been tested and does not require any special skills and/or considerable material inputs, making it feasible for implementation in healthcare. While human resource investment is necessary, the CrEAS-AC program’s design and implementation strategy aim to maximize efficiency and effectiveness. In order to further promote this intervention as soon as possible, it is recommended that training in the intervention be provided to nursing staff, with attention to fully respecting older adults’ preferences and needs, emphasizing the provision of a supportive environment, and providing positive guidance during activities. The curriculum is designed to be simple and easy to operate, with attention paid to the gradual increase in difficulty. Safe and easily accessible materials that do not require specific skills are chosen as the material for the activities. Caregivers are required to accompany and watch over the older adults throughout the program to ensure their safety.

The choice of a tertiary hospital as the trial site was driven by its advanced diagnostic and treatment facilities, along with a multidisciplinary team specializing in geriatric care and dementia. This setting enables thorough baseline assessments and ongoing monitoring throughout the study period. Additionally, it ensures that participants receive appropriate medical management in conjunction with the intervention, thereby supporting both their health needs and the study’s objectives. Owing to the limitations on human and material resources, this study only recruited study subjects in a tertiary hospital, and most of the included research population was older adults aged > 80 years old; as a result, the results may be biased to a certain extent. In the future, we can incorporate younger patients with dementia into multicenter studies in nursing homes, communities, and hospitals at all levels. Only 3 months of intervention was performed for the study subjects; because the change in cognitive function and BPSD in adults with dementia takes a longer time, the intervention time can be extended in the future to further evaluate the effect of the intervention. It is also crucial to acknowledge that our study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. This distinctive context may have influenced our findings, potentially resulting in variations compared to studies carried out before or after the pandemic.

Conclusions

This study used a randomized controlled trial approach to demonstrate that the art-based intervention (CrEAS-AC program) offers benefits for the person with dementia and his or her caregivers. It can be incorporated into non-pharmacological pre-treatment plans for dementia and long-term management strategies to help slow the progression of the disease. Further multicenter, large-sample, long-term studies are needed in the future to confirm the current findings and to fully understand the clinical value of the intervention.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Change history

01 May 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99769-0

References

Livingston, G. et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet 390, 2673–2734 (2017).

World Health Organization. Dementia. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (2023).

World Health Organization. The top 10 causes of death. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death (2020).

World Health Organization. Global status report on the public health response to dementia. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/344701/9789240033245-eng.pdf (2023).

Jia, L. et al. Dementia in China: epidemiology, clinical management, and research advances. Lancet Neurol. 19, 81–92 (2020).

State Statistical Bureau. Bulletin of the seventh national census (No.5). http://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/tjgb/rkpcgb/qgrkpcgb/202302/t20230206_1902005.html (2021).

Jia, L. F. et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and management of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in adults aged 60 years or older in China: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Public. Health 5, e661–e671 (2020).

Zhao, Q. F. et al. The prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 190, 264–271 (2016).

Acosta, I., Borges, G., Aguirre-Hernandez, R., Sosa, A. L. & Prince, M. Neuropsychiatric symptoms as risk factors of dementia in a Mexican population: a 10/66 dementia research group study. Alzheimers Dem. 14, 271–279 (2017).

Leoutsakos, J. S., Wise, E. A., Lyketsos, C. G. & Smith, G. S. Trajectories of neuropsychiatric symptoms over time in healthy volunteers and risk of MCI and dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatr. 34, 1865–1873 (2019).

Cerejeira, J., Lagarto, L. & Mukaetova-Ladinska, E. B. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Front. Neurol. 3, 73 (2012).

Van der Linde, R. M. et al. Longitudinal course of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: systematic review. Br. J. Psychiatr. 209, 366–377 (2016).

Vik-Mo, A. O., Giil, L. M., Ballard, C. & Aarsland, D. Course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: 5-year longitudinal study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatr. 33, 1361–1369 (2018).

Valimaki, T. H. et al. Impact of Alzheimer’s disease on the family caregiver’s long-term quality of life: results from an ALSOVA follow-up study. Qual. Life Res. 25, 687–697 (2016).

Lara, B., Carnes, A., Dakterzada, F., Benitez, I. & Piñol-Ripoll, G. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and quality of life in Spanish patients with Alzheimer’s disease during the COVID-19 lockdown. Eur. J. Neurol. 27, 1744–1747 (2020).

Algase, D. L. et al. Need-driven dementia-compromised behavior: an alternative view of disruptive behavior. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 11, 10–19 (1996).

Backhouse, T., Killett, A., Penhale, B. & Gray, R. The use of non-pharmacological interventions for dementia behaviours in care homes: findings from four in-depth, ethnographic case studies. Age Ageing 45, 856–863 (2016).

Magierski, R., Sobow, T., Schwertner, E. & Religa, D. Pharmacotherapy of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: state of the Art and future progress. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 1168 (2020).

British Association of Art Therapists. What is art therapy? https://baat.org/art-therapy (2022).

Fong, Z. H., Tan, S. H., Mahendran, R., Kua, E. H. & Chee, T. T. Arts-based interventions to improve cognition in older persons with mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Aging Ment. Health 25, 1605–1617 (2021).

Tan, W. J. et al. The impact of the arts and dementia program on short-term well-being in older persons with dementia from Singapore. Australas J. Ageing 41, 81–87 (2022).

Masika, G. M., Yu, D. S. F. & Li, P. W. C. Visual Art therapy as a treatment option for cognitive decline among older adults. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 76, 1892–1910 (2020).

Deshmukh, S. R., Holmes, J. & Cardno, A. Art therapy for people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 9, CD011073 (2018).

Emblad, S. Y. M. & Mukaetova-Ladinska, E. B. Creative Art therapy as a non-pharmacological intervention for dementia: a systematic review. J. Alzheimers Dis. Rep. 5, 353–364 (2021).

Richards, A. G. et al. Visual arts education improves self-esteem for persons with dementia and reduces caregiver burden: a randomized controlled trial. Dement. Lond. 18, 3130–3142 (2019).

Windle, G. et al. The impact of a visual arts program on quality of life, communication, and well-being of people living with dementia: A mixed-methods longitudinal investigation. Int. Psychogeriatr. 30, 409–423 (2018).

Lin, R. et al. Effects of creative expressive arts-based storytelling (CrEAS) programme on older adults with mild cognitive impairment: protocol for a randomised, controlled three-arm trial. BMJ Open 10, e036915 (2020).

Vaartio-Rajalin, H., Santamäki-Fischer, R., Jokisalo, P. & Fagerström, L. Art making and expressive Art therapy in adult health and nursing care: A scoping review. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 8, 102–119 (2020).

Bramer, G. R. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. Tenth revision. World Health Stat. Q. 41, 32–36 (1988).

Mo, L. et al. The effect of reminiscence therapy on behavioral and psychological symptoms in people with mild and moderate dementia. Beijing Med. J. 38, 999–1002 (2016).

Lin, R. et al. Effects of an art-based intervention in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 51, afac144 (2022).

Zhao, J. Y., Li, H., Lin, R., Wei, Y. & Yang, A. P. Effects of creative expression therapy for older adults with mild cognitive impairment at risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin. Interv Aging 13, 1313–1320 (2018).

Lin, R., Chen, H. Y., Li, H. & Li, J. Effects of creative expression therapy on Chinese elderly patients with dementia: an exploratory randomized controlled trial. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 15, 2171–2180 (2019).

Kannangara, C. The wiley handbook of Art therapy. J. Ment Health 26, 387–387 (2017).

Zhuo, X. et al. Development of an expressive Art therapy for elderly patients with mild to moderate dementia. Chin. Nurs. Manag. 23, 1286–1291 (2023).

Cummings, J. L. The neuropsychiatric inventory: assessing psychopathology in dementia patients. Neurology 48, S10–S16 (1997).

Lou, Q. et al. Comprehensive analysis of patient and caregiver predictors for caregiver burden, anxiety and depression in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Clin. Nurs. 24, 2668–2678 (2015).

Li, S. & Li, Z. Validity and reliability of the Chinese version of the Lille apathy rating scale-informant and the apathy evaluation scale-informant. Chin. Ment Health J. 32, 656–661 (2018).

Marin, R. S., Biedrzycki, R. C. & Firinciogullari, S. Reliability and validity of the apathy evaluation scale. Psychiatr. Res. 38, 143–162 (1991).

Frattali, C. M. et al. The FACS of life ASHA facs–a functional outcome measure for adults. ASHA 37, 40–46 (1995).

Chen, H. Y., Li, H., Li, J., Wei, Y. P. & Chen, P. The reliability and validity of the Chinese-version subscales of the functional assessment of communication skills. J. Nurs. Adm. 16, 572–574 (2016).

Tatsumi, H., Yamamoto, M., Nakaaki, S., Hadano, K. & Narumoto, J. Utility of the quality of life—Alzheimer’s disease scale for mild cognitive impairment. Psychiatr. Clin. Neurosci. 65, 533 (2011).

Novak, M. & Guest, C. Application of a multidimensional caregiver burden inventory. Gerontologist 29, 798–803 (1989).

Lawton, M. P. & Brody, E. M. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 9, 179–186 (1969).

Hsiao, C. Y., Chen, S. L., Hsiao, Y. S., Huang, H. Y. & Yeh, S. H. Effects of Art and reminiscence therapy on agitated behaviors among older adults with dementia. J. Nurs. Res. 28, e100 (2020).

Alonso-Lana, S., Marquié, M., Ruiz, A. & Boada, M. Cognitive and neuropsychiatric manifestations of COVID-19 and effects on elderly individuals with dementia. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12, 588872 (2020).

Vigliotti, A. A., Chinchilli, V. M. & George, D. R. Evaluating the benefits of the timeslips creative storytelling program for persons with varying degrees of dementia severity. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 34, 163–170 (2019).

D’Cunha, N. M. et al. Psychophysiological responses in people living with dementia after an Art gallery intervention: an exploratory study. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 72, 549–562 (2019).

Yan, Y. et al. Effects of a nurse-led staged integral art-based cognitive intervention for older adults on the Alzheimer’s disease spectrum: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 160, 104902 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants of this study, including the older adults and their caregivers. The authors also wish to express gratitude to all the staff and volunteers who were not named but participated, as well as those who contributed by recruiting patients and implementing intervention measures.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82071222) and Joint Funds for the Innovation of Science and Technology, Fujian province, China (No. 2020Y9021). The funders had no role in research design and collection, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript writing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Z.: writing-original draft, writing-review & editing, validation, resources, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, conceptualization. Y.Y.: writing-review & editing, resources, validation, methodology, investigation, formal analysis. R.L.: writing-review & editing, validation, resources, methodology, investigation, formal analysis. S.L.: resources, methodology, investigation. X.Z.: resources, methodology, investigation. T.S.: resources, methodology, investigation. H.Z.: resources, methodology, investigation. L.C.: writing-review & editing, resources, methodology, investigation. H.L: writing-review & editing, visualization, validation, supervision, resources, methodology, formal analysis.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article Xuefang Zhuo was omitted as equally contributing author.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhuo, X., Yan, Y., Lin, R. et al. Effects of an art-based intervention in older adults with dementia: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 15, 10406 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95051-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95051-5