Abstract

Human sleep quality is intricately linked to gut health. Emerging research indicates that Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BLa80 has the potential to ameliorate gut microbiota dysbiosis. This randomized, placebo-controlled study evaluated the impact of BLa80 supplementation on sleep quality and gut microbiota in healthy individuals. One hundred and six participants were randomly assigned to receive either a placebo (maltodextrin) or BLa80 (maltodextrin + BLa80 at 10 billion CFU/day) for 8 weeks. Sleep quality was evaluated using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), a validated tool consisting of 18 items assessing seven components of sleep quality over a one-month period, and the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), a secondary measure of insomnia severity. Gut microbiota changes were assessed using 16S rRNA sequencing, while the in vitro gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) production capacity of BLa80 was analyzed by HPLC. After 8 weeks, the intervention group exhibited a significant reduction in the PSQI total score compared to the placebo group, suggesting improved sleep quality. While no significant changes in alpha diversity were noted, beta diversity differed markedly between groups. The gut microbiota predominantly consisted of Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria and Fusobacteria, collectively accounting for over 99.9% of the gut microbiota. Statistical analysis showed that BLa80 significantly decreased the relative abundance of Proteobacteria phylum and increased the abundance of Bacteroidetes, Fusicatenbacter, and Parabacteroides compared to placebo. PICRUSt2 analysis indicated noteworthy enhancements in the pathways of purine metabolism, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, and arginine biosynthesis due to BLa80 intervention. Moreover, BLa80 demonstrated notable GABA production, potentially contributing to its effects on sleep quality modulation. These results demonstrate the ability of BLa80 to improve sleep quality through modulating gut microbiota and GABA synthesis, highlighting its potential as a beneficial probiotic strain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sleep is fundamental for maintaining cognitive functioning, and any disturbances in sleep patterns can severely impair cognitive abilities and precipitate a spectrum of adverse neurological consequences. Disrupted sleep is intricately linked with an increased susceptibility to a range of disorders, encompassing metabolic dysfunctions, neurological decline, and exacerbated psychiatric conditions1. Globally, approximately 10–15% of the population suffers from insomnia, with an additional 25–35% experiencing episodic or transient forms of insomnia, often due to increasing life pressures and various health disorders2. This condition significantly impacts immunological functions, cognitive health, emotional stability, and increases susceptibility to cardiovascular diseases3. Conventional pharmacological treatments, predominantly benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepines, are fraught with side effects, including potential dependency and withdrawal issues, which complicate long-term management strategies4. Recent scientific advancements have illuminated the potential role of the gut microbiota in modulating sleep quality. This interaction is mediated through the gut-brain axis, a complex network that integrates neuroimmune responses, endocrine signaling, and neurochemical pathways, fundamentally influencing overall health and disease states5,6,7.

Despite the established interconnections between the gut microbiota and neurological health through the gut-brain axis, the efficacy of probiotics in managing sleep disorders remains a topic of considerable debate within the scientific community. Previous research has yielded mixed outcomes; certain probiotic strains such as Lactobacillus casei Shirota and Bifidobacterium bifidum have been found to improve sleep quality in stress-impacted individuals, suggesting a potential therapeutic role in modulating neurophysiological functions8. Conversely, other studies have reported minimal to no impact on sleep parameters, highlighting a significant variability in response to probiotic interventions9. This variability underscores a critical research gap in identifying and understanding the specific probiotic strains and their mechanisms that could effectively influence sleep regulation. Building on this premise, the objective of this study is to meticulously evaluate the impact of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BLa80 on sleep quality among healthy adults. BLa80 has been preliminarily shown to affect the production of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), a pivotal inhibitory neurotransmitter that plays a crucial role in sleep regulation by reducing neuronal excitability and thus facilitating the onset and maintenance of sleep10. By focusing on this specific probiotic strain, the study aims to provide a deeper understanding of its potential benefits on sleep enhancement and the underlying biopsychological pathways.

This research is significant as it explores the potential of BLa80 as a psychobiotic with the ability to affect neurotransmitter systems and thereby improve sleep quality. Utilizing a rigorous methodological approach, this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial aims to overcome the limitations of previous studies by incorporating a biochemical analysis to assess the effects of BLa80. The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of BLa80 on sleep quality in healthy adults and to analyze its potential mechanism of action, which will provide a basis for the development of probiotic therapies to improve sleep and fill the gap in related research. The findings of this study are expected to contribute to the burgeoning field of psychobiotics, offering new insights into the mechanisms through which probiotics can influence sleep and potentially providing safer alternatives to traditional pharmacological treatments for insomnia.

Materials and methods

Participants, study design and ethical issues

The study enrolled 106 healthy volunteers aged 19 to 45 years who met the inclusion criteria and provided informed consent. PSQI and ISI scores were used in the inclusion criteria: PSQI score > 6 and < 18; ISI score > 8 and < 23. Exclusion criteria included (1) People who have been diagnosed with diabetes mellitus, or have hyperglycaemia, are not recommended to participate in the test; (2) Psychiatric or neurological disorders, celiac disease, lactose intolerance, allergies; (3) People who have medical conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome, diabetes mellitus, ulcerative colitis, etc.; (4) Recent antibiotic treatment (i.e., < 3 months prior to study entry); (5) Participants who smoked more than 10 cigarettes per day were excluded; (6) Others with special conditions are not recommended to participate, such as those who are allergic to probiotic products; (7) Pregnant and lactating women and people under 19 and over 45 years of age should not be experimented with.

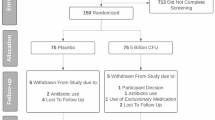

The study was conducted at Henan University of Technology from October 30, 2023, to January 5, 2024. All participants underwent a comprehensive screening process to ensure compliance with study requirements. To minimize external influences, participants ceased all probiotic supplements two weeks prior to enrollment. The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines and received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Henan University of Technology (Approval No. HautEC2366), and was registered in the Registry of Clinical Trials (NCT06107049, first posted date 30/10/2023) (Fig. 1).

Experimental design

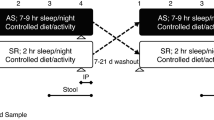

This study was conducted as a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial comprising two groups: the placebo group, which received a daily dose of 3 g maltodextrin, and the BLa80 group, which was administered 2.9 g maltodextrin alongside 0.1 g BLa80 bacterial powder, equivalent to 10 billion CFU, provided by Wecare Probiotics Co., Ltd. ISO 15214:1998 was used to determine the dosage. Our strain, BLa80, predominantly produces lactic acid11.

Participants underwent a 14-day washout period devoid of any probiotic products prior to the trial. Throughout the trial, participants were advised to adhere to their usual dietary and lifestyle routines without any additional restrictions. During the trial, the only restriction was not to consume any other foods that explicitly contain prebiotics or probiotics. The study protocol included two visits. The initial visit (T0) involved baseline measurements of height and weight. These parameters, along with BMI (Body Mass Index), were subsequently monitored on a weekly basis until the end of the study (T1). InBody Body Composition Analyzers were used to determine the body fat percentage. The intervention’s effects on bowel movements were evaluated using a standardized questionnaire. To mitigate individual variability and provide a robust comparison, a longitudinal study design was employed, with T0 samples serving as controls. At the concluding visit (T1), we collected fecal samples and performed a comprehensive gut microbiota analysis of these samples by DNA extraction and sequencing techniques, as shown in Fig. 2. This methodological framework was meticulously designed to ensure a thorough assessment of the intervention’s influence on the composition of the gut microbiota and overall participant health outcomes, thereby contributing significant insights into the probiotic’s therapeutic potential.

DNA extraction and sequencing for fecal samples

Participants were instructed to self-collect fecal samples, which were immediately frozen at -20°C and subsequently transported to the laboratory for long-term storage at -80°C until analysis. DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA kit in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) targeted the V3–V4 variable regions of the 16S rRNA gene, employing primers F1 (5’-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3’) and R2 (5’-GACTACHVGGTATCTAATCC-3’). High-throughput sequencing was conducted on the Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), generating paired-end reads of 300 base pairs each. A previously sequenced positive control was included to ensure the consistency and reliability of the DNA extraction and PCR processes.

Sleep quality assessments

Sleep quality was primarily evaluated using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), which quantifies sleep quality over a one-month interval. The PSQI consists of 18 items forming seven components: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction. Each component is scored from 0 (no difficulty) to 3 (severe difficulty), with the total score ranging from 0 to 21, where higher scores denote poorer sleep quality. A global PSQI score over 7 indicates significant sleep issues. The questionnaire, which takes approximately 5 min to complete, was administered to participants at baseline and at the eight-week follow-up through structured interviews. Additionally, the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) was used as a secondary measure to further assess sleep quality nuances.

Measurement of GABA content

Medium Preparation and Sterilization MRS broth was enhanced with 4–6 mm of liquid paraffin and either cysteine or nonyl cyanide, autoclaved, and transferred into anaerobic culture bags for bacterial growth.

Inoculation and Culture Bacterial strains from glycerol stocks were streaked tri-zonally onto solid MRS media, isolated, and purified over three rounds. Pure colonies were then expanded in liquid media at 37 °C for 48 h, with subsequent strain confirmation via 16S rRNA sequencing.

GABA-Producing Strains Culture Activated strains were incubated in MRS broth with 1% sodium L-glutamate at 37 °C, statically for 48 h.

Sample Processing of Culture Supernatant (1) Centrifugation and Separation: After the culture is complete, centrifuge the bacterial suspension at 12,000 r/min for 15 min. Discard the bacterial pellet and carefully aspirate the supernatant using a sterile pipette. (2) Storage Conditions: Immediately after centrifugation, transfer the supernatant into sterile centrifuge tubes. For short-term storage (≤ 48 h), keep the supernatant at -20 °C. For long-term storage or if analysis is delayed, store the supernatant at -80 °C. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles. (3) Pre-analysis Sample Processing: Before analysis, thaw the frozen samples at 4 °C and filter them through a 0.22 μm sterile membrane filter to prepare for GABA analysis.

GABA Quantification Quantification was conducted using HPLC with an Agilent TC-C18 column, maintaining a 1 mL/min flow rate and 35 °C column temperature, with a 5 µL sample injection. Mobile phase and derivatization specifics are detailed in supplementary materials.

Bioinformatic analysis

We employed bioinformatic methodologies to analyze amplicons, as described in our prior article by Dong et al.12. Trimmomatic13 was employed to eliminate low-quality sequences. The reads were grouped together based on their similarities to generate amplicon sequence variations (ASVs). Denoising, classification assignment, and the creation of ASV tables were carried out using the USEARCH programme (version 11.0667), which may be accessed at https://drive5.com/usearch/. The reference database for sequence annotation was the 16S rRNA database from the RDP Reference Training Set (version 18) (https://www.drive5.com/usearch/manual). We utilised the vegan 2.5-7 package to analyse the community diversity (measured by Shannon and Simpson indices) and richness (measured by Chao1 and abundance-based coverage estimators [ACE]) of the gut microbiota at the ASV level, as described in the study by Oksanen et al. (2020). The 16S rRNA sequencing data were analysed using the PICRUSt v2.5.0 (Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States) pipeline, specifically the picrust2_pipeline. The “py” command was used to forecast alterations in the functional composition of the faecal microbiome by relying on the estimated proportions of KEGG pathways in each sample14.

Statistical analysis

The t-test was used to analyse continuous data that followed a normal distribution. The nonparametric test was used to analyse continuous data that deviated from the normal distribution in order to identify any disparities between the two groups. The gut microbiota data were subjected to Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) using the Bray-Curtis distance metric. The adonis2 function from the vegan 2.5-7 package was used to identify significant changes between groups. The PICRUSt data were examined using the Statistical Analysis of Metagenomic Profiles (STAMP, version 2.1.3) software15. The ggplot2 package in R16 was used to generate all plots. The statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.3, and p-values less than 0.05 were deemed statistically significant.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

The datasets generated during this study are included in this article. The 16S rRNA gene sequence from human fecal samples is accessible in the NCBI genome database under accession PRJNA1094618.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the individuals

The trial comprised a total of 106 participants, with 4 individuals being excluded due to non-compliance with the inclusion criteria or personal reasons (Fig. 1). The overall design of the trial and the intervention period are shown in Fig. 2. Table 1 demonstrates that there were no significant differences in age, gender, height, and BMI between the two groups at the beginning of the study.

Differences in physical metrics pre- and post-intervention

The GSRS (Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale) was used to assess the intestinal motility of the participants. As shown in Table 1, at the beginning of the trial, the placebo and BLa80 groups did not show significant differences in gender, age, BMI, GSRS scores, PSQI, and ISI. Looking further at the data in Table 2, we found that no significant changes were seen in the PSQI and ISI scores of the two groups at week four, as well as in the ISI, GSRS scores, and BMI at week eight. However, it is noteworthy that at week eight there was a significant decrease in PSQI scores in the BLa80 group compared to the placebo group. This result reflects, to some extent, that BLa80 supplementation has demonstrated an effect on improving sleep quality while ensuring safety.

Differences in sleep quality indexes pre- and post-intervention

In the present study, the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index Scale (PSQI) and the Insomnia Severity Index Scale (ISI) were used to assess the sleep quality and insomnia of subjects. The statistical analysis of PSQI data showed that BLa80 intervention had limited effect on the overall sleep quality, and there was no significant effect on the total PSQI score, sleep duration, deep sleep ratio, and sleep efficiency between the intervention group and the control group. However, there was a significant difference in sleep onset time and daytime dysfunction (p < 0.05). Participants reported a significant reduction in the time to fall asleep and a significant reduction in dysfunction of feeling sleepy or low energy during the day. ISI data showed that the improvement in insomnia per capita in the BLa80 intervention group was higher than that in the placebo group, but there was no significant difference in the statistical analysis.

GABA measurement results

According to the chromatogram of the standard product, the peak time of GABA was 5.4 min, and the standard curve of GABA was plotted (Fig. 3A). As provided in supplementary material, standard curve was generated with series solution ranging from 0.02 to 0.08 mg/ml (y = 23931x + 21.08, R2 = 0.9964).

Comparing to the GABA standard HPLC result in Fig. 3B, the result of Fig. 3C shows that a certain amount of GABA was detected in the BLa80 sample, and its peak time was about 5.4 min, which was the same as that of the standard. The GABA content was calculated according to the standard curve, and the BLa80 was able to produce 5 µg/ml.

Effects of BLa80 supplementation on gut microbiota diversity

Gut Microbiota abundance and diversity were analyzed. PCoA analysis showed that BLa80 intervention had a significant effect on the beta diversity of the gut microbiota (p = 0.046) but not on the gut microbiota’s abundance (Chao1 and ACE index) or diversity (Shannon and Simpson) (Fig. 4A and B). As shown in Fig. 4C, there was no significant difference in bacterial alpha diversity in the BLa80 group compared to the placebo group after 8 weeks of intervention.

Effect of BLa80 supplementation on gut microbiota structure in healthy volunteers. (A) Species accumulation curves of BLa80 and Placebo groups. (B) Effect of BLa80 intervention on beta diversity of the gut microbiota. (C) Effect of BLa80 intervention on alpha diversity of gut microbiota. D, Effect of BLa80 intervention on gut microbiota at phylum level.

At the phylum level, the gut microbiota mainly consisted of Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria and Fusobacteria, accounting for more than 99.9%. In addition, as shown in Fig. 4D, statistical analysis found that BLa80 intervention could significantly reduce the relative abundance of Proteobacteria compared to the placebo group.

Genus-level variation and functional analysis of the gut microbiota

Variation in the composition of the gut microbiota at the genus level was further investigated by STAMP. As shown in Fig. 5A, BLa80 intervention significantly increased the relative abundance of Bifidobacterium, Fusicatenbacter and Parabacteroides.

In functional analysis, PICRUSt2 was used to analyze and predict the functional genes in the gut microbiota. As shown in Fig. 5B, PICRUSt2 analysis showed similar changes in microbiota function in both the placebo and BLa80 groups, consistent with the results of the STAMP analysis. BLa80 intervention significantly enriched the relative abundance of purine metabolism, Glycolysis gluconeogenesis, and Arginine biosynthesis.

Discussion

This randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial investigated the effects of BLa80 on sleep quality, employing both subjective measures (PSQI and ISI scores) and objective analyses of gut microbiota and in vitro GABA production. This approach provides a framework for assessing the therapeutic potential of BLa80 as a safer alternative to conventional sleep aids, which are often associated with significant side effects and dependency risks4.

In our study, the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) served as primary tools for measuring subjective sleep quality. The reliability of these questionnaires in assessing sleep disorders has been well recognized and verified within clinical research17. However, it is crucial to acknowledge the inherent limitations associated with self-reported data, which can be influenced by various factors, including cognitive biases, current emotional state, and societal perceptions of health interventions. Currently, the widespread popularity of probiotics and the public’s strong belief in their health benefits could potentially influence participants’ subjective responses in studies evaluating their effects18. Interestingly, a previous study employing magnetic resonance imaging to explore the influence of probiotics on mood demonstrated significant changes even within the placebo group19. This suggests that the placebo effect was not only reflected in subjective scores, but also in objective data. Self-reports are susceptible to interference from a variety of factors such as current situations, nonverbal cues, and memory biases. This finding underscores the complexity of the placebo effect, which not only impacts subjective assessments but can also manifest in objective measurements, suggesting a psychophysiological response to the placebo intervention. In this trial, participants in both the BLa80 group and the placebo group demonstrated an overall downward trend in PSQI and ISI scores, a result that suggests an improvement in their sleep quality. Specifically, PSQI scores declined at a statistically significant level, showing a clear improvement. In contrast, although the mean ISI scores also decreased and insomnia may have been reduced, this change did not reach a statistically significant level, implying that the statistical significance of the improvement is uncertain and must be treated with caution due to the possibility of a placebo effect, which is a frequently observed occurrence in experiments that involve subjective outcomes20. Despite the reported improvements in clinical outcomes, this effect was still apparent, emphasising the importance of implementing strict controls and objective metrics in future research to distinguish genuine therapeutic advantages from placebo reactions.

Given the inherent limitations of self-report measures, which have long been scrutinized by psychologists and psychiatrists for their accuracy, this study also incorporated objective analyses of gut microbiota and GABA production. BLa80 intervention notably increased beta diversity and reduced the Proteobacteria population at the phylum level, aligning with evidence that dysbiosis in the gut microbiome may be linked to psychiatric disorders. This suggests potential therapeutic and preventative applications for gut microbiome modulation. For instance, Jiang et al. reported elevated levels of Proteobacteria and Enterobacteriaceae in patients with depressive disorders compared to healthy controls21, highlighting the association between microbial imbalances and mental health. The instability often seen in the Proteobacteria phylum can indicate an imbalance or structural instability within the gut microbial community, necessitating further investigation into the causes of these fluctuations to develop effective interventions22.

At the genus level, BLa80 notably enhanced pathways related to purine metabolism, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, and arginine biosynthesis, which are crucial metabolic pathways implicated in mental health23. Literature demonstrates a strong association between abnormalities in purine and pyrimidine metabolism and various psychiatric conditions including anxiety, depression, and sleep disorders24. Previous studies have also connected the dysregulation of these metabolic pathways with depressive symptoms and sleep disturbances25,26,27, and even broader cognitive dysfunctions, such as those seen in neurodegenerative diseases and Alzheimer’s disease. Our findings suggest that the modulation of these metabolic pathways by BLa80 may contribute to the observed improvements in sleep quality. This hypothesis is supported by the intervention’s impact on purine and pyrimidine metabolism, providing a possible mechanism for its effects on both gut health and sleep quality, underscoring the integrated role of metabolic pathways in neuropsychiatric health. Arginine biosynthesis has been identified as significantly linked with stress management, which is crucial considering the role of stress as a predominant factor in the onset of insomnia episodes28. This connection speculates how BLa80 may influence sleep quality through the modulation of neurotransmitters involved in stress responses.

On another note, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) serves as the central nervous system’s primary inhibitory neurotransmitter, regulating key physiological processes including the sleep-wake cycle, motor functions, and vascular tone. GABA contributes to brain homeostasis and function by binding to its receptors and reducing neuronal excitability. In the realm of probiotics, Bifidobacterium bifidum is renowned for its potent GABA-producing capabilities. Research indicates that Bifidobacteria can generate up to 6 g/L of GABA during growth, positioning it as a promising probiotic for boosting GABA levels through dietary intake or supplements, thus offering substantial health benefits. To explore the GABA-producing capability of BLa80, an in vitro experiment was conducted using a liquid chromatography method that confirmed BLa80’s capacity to produce GABA. Based on these findings, there is potential to optimize the fermentation medium or employ fecal co-culture techniques to further assess GABA production. The ability of BLa80 to synthesize GABA is not only pertinent to its impact on host health but also opens new avenues for treating neuropsychiatric disorders. Consequently, the GABA synthesizing ability of BLa80 may be a significant aspect of its probiotic potential, offering speculate insights into innovative strategies for managing sleep disorders and enhancing mental health.

Our study has identified key limitations that need to be addressed in subsequent research. The demographic restriction to young and middle-aged Chinese participants and potential gender disparities in the treatment group suggest that our findings may not be universally applicable. Besides, as our previous research supported the assumption, the fecal samples at T0 were not collected29. The absence of initial fecal samples limited the scope for pre- and post-intervention comparisons. Furthermore, future studies should consider a more diverse demographic and increase the number of sampling points to accurately reflect the dynamic nature of gut microbiota changes. Also, more metabonomics research were needed to demonstrate the relationship between BLa80 GABA production and sleep quality improvement in BLa80 intervened participants. Additionally, the influence of dietary variations on gut microbiota underscores the necessity for stricter dietary controls in future trials to better isolate and understand the specific effects of probiotic interventions on gut health.

Conclusion

In summary, the administration of BLa80 has demonstrated a regulatory effect on gut microbiota, significantly enhancing the abundance of Bifidobacterium while reducing levels of Proteobacteria. Following an 8-week intervention, participants in the BLa80 group showed markedly lower PSQI scores compared to those in the placebo group, indicating improved sleep quality. Additionally, the intervention notably increased the relative abundance of Bifidobacterium, Fusicatenbacter, and Parabacteroides. Metabolic pathway analysis via PICRUSt2 revealed significant upregulation in purine metabolism, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, and arginine biosynthesis pathways. These findings underscore BLa80’s capability to enhance sleep quality, potentially through synergistic effects on GABA production and gut microbiota modulation. Collectively, these attributes position BLa80 as a highly promising probiotic strain with beneficial implications for sleep health.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the NCBI genome database under accession PRJNA1094618.

References

Wang, Y. H. et al. Association of longitudinal patterns of habitual sleep duration with risk of cardiovascular events and All-Cause mortality. JAMA Netw. Open. 3 (5), e205246 (2020).

Irwin, M. Effects of sleep and sleep loss on immunity and cytokines. Brain. Behav. Immun. 16 (5), 503–512 (2002).

Fortier-Brochu, É. & Morin, C. M. Cognitive impairment in individuals with insomnia: Clinical significance and correlates. Sleep 37 (11), 1787–1798 (2014).

Cunnington, D., Junge, M. F. & Fernando, A. T. Insomnia: Prevalence, consequences and effective treatment. Med. J. Aust. 199 (8), S36–40 (2013).

Hu, S. et al. Gut microbiota changes in patients with bipolar depression. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 6 (14), 1900752 (2019).

Dinan, T. G., Stanton, C. & Cryan, J. F. Psychobiotics: A novel class of psychotropic. Biol. Psychiatry. 74 (10), 720–726 (2013).

Cryan, J. F., O’Riordan, K. J., Sandhu, K., Peterson, V. & Dinan, T. G. The gut Microbiome in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 19 (2), 179–194 (2020).

Takada, M. et al. Beneficial effects of Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota on academic stress-induced sleep disturbance in healthy adults: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Beneficial Microbes. 8 (2), 153–162 (2017).

Diop, L., Guillou, S. & Durand, H. Probiotic food supplement reduces stress-induced Gastrointestinal symptoms in volunteers: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Nutr. Res. 28 (1), 1–5 (2008).

Gao, S. F. & Bao, A. M. Corticotropin-releasing hormone, glutamate, and γ-aminobutyric acid in depression. Neuroscientist 17 (1), 124–144 (2011).

Dong, Y., Han, M., Fei, T., Liu, H. & Gai, Z. H. Utilization of diverse oligosaccharides for growth by bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species and their in vitro co-cultivation characteristics. Int. Microbiol. 27, 941–952 (2024).

Dong, Y. et al. Bifidobacterium BLa80 mitigates colitis by altering gut microbiota and alleviating inflammation. Amb Express 12(1). (2022).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30 (15), 2114–2120 (2014).

Langille, M. G. I. et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 31 (9), 814– (2013).

Parks, D. H., Tyson, G. W., Hugenholtz, P. & Beiko, R. G. STAMP: statistical analysis of taxonomic and functional profiles. Bioinformatics 30 (21), 3123–3124 (2014).

Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis, vol. 16; (2009).

Irwin, C., McCartney, D., Desbrow, B. & Khalesi, S. Effects of probiotics and paraprobiotics on subjective and objective sleep metrics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 74 (11), 1536–1549 (2020).

Lee, H. J. et al. Effects of Probiotic NVP-1704 on Mental Health and Sleep in Healthy Adults: An 8-Week Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients 13(8). (2021).

Tillisch, K. et al. Consumption of fermented milk product with probiotic modulates brain activity. Gastroenterology 144 (7), 1394–1401e1394 (2013).

Talaei, A., Hassanpour Moghadam, M., Sajadi Tabassi, S. A. & Mohajeri, S. A. Crocin, the main active saffron constituent, as an adjunctive treatment in major depressive disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot clinical trial. J. Affect. Disord. 174, 51–56 (2015).

Jiang, H. et al. Altered fecal microbiota composition in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav. Immun. 48, 186–194 (2015).

Shin, N. R., Whon, T. W. & Bae, J. W. Proteobacteria: microbial signature of dysbiosis in gut microbiota. Trends Biotechnol. 33 (9), 496–503 (2015).

Xiong, Y. et al. Dynamic alterations of the gut microbial pyrimidine and purine metabolism in the development of liver cirrhosis. Front. Mol. Biosci. 8, 811399 (2021).

Tanihiro, R. et al. Effects of prebiotic yeast Mannan on gut health and sleep quality in healthy adults: A randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled study. Nutrients 16(1). (2024).

Zhou, X. et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids metabolism, purine metabolism and inosine as potential independent diagnostic biomarkers for major depressive disorder in children and adolescents. Mol. Psychiatry. 24 (10), 1478–1488 (2019).

Park, D. I. et al. Purine and pyrimidine metabolism: convergent evidence on chronic antidepressant treatment response in mice and humans. Sci. Rep. 6 (1), 35317 (2016).

Doke, M., McLaughlin, J. P., Baniasadi, H. & Samikkannu, T. Sleep disorder and cocaine abuse impact purine and pyrimidine nucleotide metabolic signatures. Metabolites 12(9). (2022).

Holsboer, F. & Ising, M. Stress hormone regulation: Biological role and translation into therapy. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 61 (61, 2010), 81–109 (2010).

Gai, Z. et al. Changes in the gut microbiota composition of healthy young volunteers after administration of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus LRa05: A placebo-controlled study. Front. Nutr., 10. (2023).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support from the Henan Province Key Science and Technology Research Program (22B550001), Provincial natural science youth fund project (232300420207) from Science and Technology Department of Henan Province.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YHL: conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis, fundraising. YYC: conceptualization, data maintenance, methodology, software, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing. FX: acquisition of funds, project management, writing- original design, resources, supervision, formal analysis, software, validation, visualization. QYZ & YYZ: data curation, investigation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Chen, Y., Zhang, Q. et al. A double blinded randomized placebo trial of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BLa80 on sleep quality and gut microbiota in healthy adults. Sci Rep 15, 11095 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95208-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95208-2