Abstract

Background Patients with hematological malignancies (HMs), particularly those who have undergone bone marrow or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), are at greater risk for morbidity and mortality due to immunosuppression. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these vulnerabilities in HM patients, although comprehensive data specifically on HSCT recipients are limited. Objective This study investigated the clinical and demographic profiles of HSCT recipients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Spain. We also identified factors associated with in-hospital mortality in HSCT patients. Methods We conducted a nationwide, retrospective analysis using data from the Spanish National Health System. We included hospitalized patients with HMs and COVID-19 infection from 2020 to 2022. We used descriptive statistics, multivariate logistic regression, and survival analyses to assess predictors of mortality. Results In total, 35,648 patients with HMs were included, of whom 2,324 (6.5%) had undergone HSCT. The in-hospital mortality rate for HSCT recipients was 13%, lower than the 20% observed in non-HSCT patients. Older age, dementia, acute leukemia, and solid tumors were independently associated with increased mortality. In spite of their immunosuppressed state, HSCT recipients experienced relatively favorable outcomes, suggesting partial immune recovery following transplantation. Conclusions HSCT recipients with COVID-19 present different clinical characteristics and mortality risks than non-recipients. These findings indicate the need for specific management strategies for this vulnerable population. Further research is needed to explore immunological recovery and the transplant-specific factors that may influence COVID-19 outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), posed significant challenges to national healthcare systems between 2020 and 20221,2. It had a great impact on humanity, with 6.7 million confirmed deaths by December 20223with a particularly large impact on vulnerable populations4,5,6.This includes patients with hematological malignancies (HMs), who are a high-risk group for several reasons including underlying immune dysregulation due to the nature of their hematologic dysfunction, disease-specific complications, their lack of an appropriate response to vaccines, and intensive treatment regimens that cause deeper immune dysfunction7,8,9,10. Such aggressive management involves immunosuppressive chemotherapy, which, combined with disease-related immunodeficiency, predisposes these patients to severe viral, bacterial and fungal infections, including by SARS-CoV-2. Poorer clinical outcomes related to COVID-19 have been reported in hematologic patients relative to the general population6,11.

Among patients with HMs, those who have undergone bone marrow or hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT) are a particularly vulnerable subset who require special attention. HSCT recipients have prolonged immune reconstitution periods, during which they remain highly susceptible to infections and complications related to immune dysfunction12,13,14. This increased vulnerability is due to a combination of several other factors, including preexisting comorbidities, graft-versus-host disease, and prolonged exposure to healthcare environments15,16. The combination of these factors with SARS-CoV-2 infection highlights the importance of understanding the clinical and demographic characteristics of populations with HSCT.

We analyzed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic at a national level in hospitalized, hematologic patients with HSCT. The objective was to provide a comprehensive picture of patients with HMs who received HSCT, describing their demographic and clinical profiles during the pandemic. We also identified risk factors associated with mortality in HSCT recipients using a large dataset to have greater insights into their management.

Methods

Study design and population

We conducted a nationwide, retrospective study including patients with HMs who were hospitalized in Spain during the first 3 years of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2022). Data were extracted and collected from the Minimum Basic Data System at Hospitalization (MBDS-H) database provided by the Spanish National Health System. This is an administrative registry that includes demographic and clinical data extracted from hospitalization discharge reports. We collected data for approximately 35,000 patients with HMs, of whom 2,300 had undergone HSCT before or during the pandemic.

Data collection

MBDS-H uses discharge reports from nearly 95% of both public and private hospitals in Spain. It is estimated that 97% of all discharge reports are collected in this registry. The registry collects several demographic and clinical variables from patients: age, sex, date of admission/discharge, type of hospital, place of residence, ICU admission, time and occurrence of death (if applicable), and diagnosis/diagnoses at discharge. Diagnoses are encoded using the 10th Clinical Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10-CM). We collected data using the coding for COVID-19 (U07.1) at any diagnostic position. We also identified codes on HMs including Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, multiple myeloma and plasma cell disorders, acute and chronic leukemia (lymphoid, myeloid, and monocytic), and myeloproliferative disorders (polycythemia vera, essential thrombocytosis, myelofibrosis, and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia). The patients were classified in relation to their HSCT status and were analyzed separately. We did not categorize groups by allogeneic or autologous HSCT due to the characteristics of the registry. We also identified certain comorbidities of interest, such as diabetes, hypertension, and other chronic conditions. No names or personal information were recorded, so the data were provided in a de-identified form to ensure patient privacy. No data on treatment or immunological status were provided. This study was approved by the research ethics committee of our institution.

A major limitation of the registry used is that a new dataset is generated in January of each year. Due to the large amount of data, the availability of the database has a delay of 1 year. Thus, Spanish Ministry of Health provided us with data through 31 December 2022.

Statistical analyses

We first performed descriptive and correlational analyses. Demographic and clinical characteristics were expressed using medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical ones. Correlational analyses were performed using the chi-square test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables.

We used multivariate logistic regression models to identify the risk factors associated with mortality in HSCT recipients. We included all variables, not only statistically significant (p < 0.05) ones, in univariate analyses. We used stepwise regression to fit the logistic regression model. This automatic procedure eventually chooses relevant, predictive variables. We adopted bidirectional elimination as the main approach for stepwise regression. The results from the fitted model are presented as univariate and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

For survival analysis, we used Cox proportional hazards regression models to identify predictors of mortality, and hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated. Mortality was considered the dependent variable, and length of stay was used as the time-to-event variable. Later, the proportional hazards assumptions were verified using Schoenfeld residuals.

Statistical analyses were conducted using R language version 4.3.2 (Vienna, Austria) on a Debian 12 GNU/Linux workstation. For all tests, the level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethical Board of Universidad Rey Juan Carlos (ID number 2610202334423). No identifying information was included in the manuscript. Because the authors used historical data, the Ethical Board considered informed consent was not necessary. So, the need for informed consent to participate was waived by our Ethical Board. All procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Results

Descriptive analyses

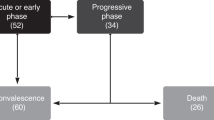

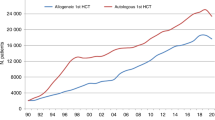

We collected data from 35,648 patients with HMs who were hospitalized with a COVID-19 diagnosis in 2020–2022. In this group, we identified 2,324 patients who had undergone an HSCT before or during the hospitalization. Table 1; Fig. 1 summarize the descriptive results of the cohort. During the 3-year period studied, we observed an increased number of hospitalizations among hematologic patients in 2022, with 17,342 hospital admissions (49% of all admissions) compared to 2020 and 2021. This increase was observed in patients both with and without HSCT (48% and 52%, respectively). There were more males than females in both groups, with the difference being greater among HSCT recipients (62% male). HSCT recipients were younger than non-recipients (median ages of 75 vs. 58 years old) and had a higher rate of ICU admissions. Mortality was significantly higher in those who did not undergo HSCT (20% vs. 13%, p < 0.001).

Regarding underlying HMs, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, acute leukemias, and chronic myeloproliferative disorders were more frequent in non-recipients, while multiple myeloma and malignant plasma cell neoplasms were more frequent in recipients. There were no differences regarding Hodgkin lymphoma between the groups.

Apart from chronic liver disease, chronic conditions were more prevalent in the non-recipient group.

Next, we analyzed the data for a subset of recipients that underwent HSCT, as shown in Table 2.

Among the 2,324 hospitalizations, there were 302 deaths (13%). Mortality was higher in 2022 than in the previous 2 years (118 individuals, 39%). The patients who died were older than those who survived (61 vs. 58 years old, p = 0.004). Men were more common in the two groups, regardless of survival status. ICU admissions, ICU length of stay, and hospitalization length of stay were also higher in patients who died, probably as surrogates of severity. Heart failure, dementia, and the presence of a solid neoplasm were highly correlated with mortality as comorbidities. Acute leukemias and chronic myeloproliferative disorders were the HMs that were more associated with mortality in HSCT recipients.

Figure 2 shows the evolution of mortality as both a time series plot (absolute count) and as a bar plot chart (percentage).

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression

We performed logistic regression to assess the effects of demographic and clinical characteristics, comorbidities, and HMs on in-hospital mortality due to COVID-19 in the cohort of patients with HM. In univariate analyses, HSCT status did not show a significant effect on COVID-19-related mortality (OR = 1.01, 95% CI: 0.89–1.14, p = 0.88). After adjusting for variables such as age, comorbidities, and type of hematologic malignancy in the multivariate analysis, HSCT was also not associated with an independent reduction in mortality (adjusted OR = 1.08, 95% CI: 0.94–1.24, p = 0.27). Then we developed a logistic regression model in the cohort of HSTC recipients only. This model evaluated the effect of age, sex, comorbidities, and HMs. Table 3 shows the results of univariate and multivariate analyses. Age and dementia were risk factors for mortality. ICU admission significantly predicted in-hospital survival (OR = 0.13, CI 0.09–0.19, p < 0.001), highlighting the protective effect on mortality. The presence of solid neoplasms and acute leukemias were also major risk factors for mortality (OR = 3.63 and OR = 1.72, respectively).

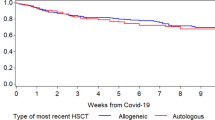

Survival analysis

Next, we explored predictors of in-hospital mortality. To evaluate time-to-event data, we conducted a survival analysis with the Cox proportional hazards model, as shown in Table 4. The dependent variable was in-hospital mortality, and the time-to-event was defined as the length of hospital stay in days. As is done in logistic regression, we included all demographic variables, clinical factors, comorbidities, and HMs. As mentioned in the Methods section, we applied stepwise regression including bidirectional elimination to refine predictor selection. Thus, the model automatically included the relevant variables and excluded the nonsignificant ones. As with the logistic regression model, we identified the following predictors for in-hospital mortality: age, dementia, solid tumors, and acute leukemias. Of note, ICU admission was again associated with a lower HR, reflecting that intensive care was a likely protective factor in severe cases.

Discussion

This nationwide study investigated the clinical and demographic profiles of HSCT recipients who also had an underlying HM and who were hospitalized during the COVID-19 pandemic. We also identified predictors for in-hospital mortality in this population. Our results provide insight into the patient characteristics of this population, and their risk factors for mortality, highlighting their vulnerabilities and elucidating their clinical course and outcomes.

Among the 2,324 HSCT recipients, the overall in-hospital mortality rate was 13%, notably lower than the 20% observed in non-HSCT patients. This difference highlights the complexity of HSCT patients, as this finding can be counterintuitive. When analyzed the entire cohort of 35,648 patients with HMs, our univariate and multivariate analyses did not show an independent protective effect of HSCT on COVID-19-related mortality. This finding contrasts with the lower mortality observed in transplanted patients compared to those who did not undergo HSCT (13% vs. 20%, p< 0.001). The apparent survival advantage in transplanted patients may be explained by selection factors, such as the inclusion of younger patients and those with fewer comorbidities in the HSCT group, rather than a direct effect of transplantation on immunity against COVID-19. Additionally, the lack of detailed data on the type of transplant (allogeneic vs. autologous) and pre-infection immunological status limits our ability to assess the specific impact of HSCT on clinical outcomes.

According to a recent narrative review, reports of COVID-19-related mortality among HSCT recipients are mostly based on single-center studies; those from multicenter studies involved a low number of individuals17. The review also indicated significant heterogeneity in patients, clinical settings, inclusion criteria, follow-up periods, and outcomes. Furthermore, most of these studies were conducted during the early pandemic, before vaccines and other specific treatments were yet available. Hence, the mortality rate among HM patients may be overstated. Nonetheless, it is clear that mortality in hematologic patients, regardless of HSCT status, is increased relative to the general population. However, there is evidence that morbidity and mortality outcomes may vary significantly between hematologic patients who do and who do not undergo HSCT. For example, Shah et al.18, found that, while HSCT recipients experienced high mortality (up to 22%), they had favorable outcomes compared to non-HSCT recipients. They interpreted their findings as being due to the adaptive immune response after HSCT against COVID-19. Thus, HSCT patients are able to modulate immune reconstitution following transplantation19,20. Although SARS-CoV-2 infection may cause lymphopenia in severe cases, HSCT recipients are able to recover T cells, in spite of marked lymphopenia and circulating B cells. Indeed, such patients can produce SARS-CoV-2 antibodies18,21. A later meta-analysis of 19 studies including 2,031 HSCT recipients reported a median age of 57 years, similar to our findings, and a mortality rate of 19%22.

In our study, we found that mortality was higher in 2022, albeit specifically in the first months of the year. This may reflect the evolution of the pandemic in terms of SARS-CoV-2 variants. The omicron subvariants BA.4, BA.5, and BA.2.75 were predominant in Spain beginning in the first months of 2022. They were reported to be more immune-evasive, and although they only caused mild disease in healthy individuals, they could cause severe disease in vulnerable populations, such as the elderly or immunocompromised, during these months6,23.

In line with previous studies, older age at diagnosis of COVID-19 was associated with poor outcomes24. We likewise found that dementia and leukemia were significant predictors of mortality, in both logistic regression and survival analyses. Dementia is associated with age, probably reflecting a certain degree of multicollinearity between these two variables. These comorbidities may be key determinants of poorer outcomes, not only in HSCT recipients, but also more generally in patients with HMs18,25.

We found that acute leukemias were also significantly associated with mortality, likely due to their aggressive clinical course and the profound immunosuppression inherent in their management26. Our results align with those of Sharma et al.14, who included 318 patients diagnosed with COVID-19 in a survival analysis and studied mortality during the first months of the pandemic. They found that solid tumors, plasma cell disorders (i.e., multiple myeloma and malignant plasma cell neoplasms), and lymphoma were relevant predictors of mortality. Our results also support Shah et al.18. , who also found that active malignancy, particularly leukemia, was associated with mortality in HSCT recipients.

In our study, ICU admission was also predictive of mortality in both logistic regression (OR = 0.13, 95%CI 0.09–0.19, p < 0.001) and in survival analysis (HR = 0.42, 95%CI 0.31–0.56, p < 0.001). However, it may act as a confounding factor rather than a direct protective factor, and our finding requires careful interpretation. We believe that this is likely to have been influenced by survivorship bias. That is, patients who survive long enough to be admitted to the ICU are younger or have a less severe case of the disease and may inherently differ from those who did not match ICU admission criteria. The latter group of patients might experience rapid clinical deterioration or death before ICU admission. Furthermore, ICU admission could act as a surrogate marker for the availability and intensity of advanced medical care, not as a factor that directly mitigates mortality risk. Thus, this finding should be interpreted with caution, and clinicians should consider their clinical decision-making and resource availability when interpreting the role of ICU admission in morbidity and mortality risk among HSCT recipients. Indeed, future studies would benefit from incorporating additional variables, such as the timing of ICU admission, the onset of clinical deterioration, the management of complications, and the immunological status of patients prior to assessing the role of ICU admission as a potential confounder versus a direct protective factor.

Limitations and strengths

The potential limitations of our study include the inherent characteristics of the registry data itself. Detailed immunological and treatment data were not available. We did not collect information on graft type, i.e., allogeneic and autologous HSCT. In addition, we lacked data on the year of transplantation, as these data were not available in the administrative dataset. Patients with graft-versus-host disease were not identified. More importantly, no information on the immunologic profile before the SARS-CoV-2 infection (CD4+/CD8 + count) or on the status of the HM (relapse or progression of disease after transplantation) were available. We could not assess the impact of specific treatments such as corticosteroids, antivirals, or immunosuppressive therapies on mortality.

The lack of data on immunologic status, the diversity of graft sources, and the distinct immunosuppression therapies employed may have impacted the interpretation of our findings, although we focused on trends over time and the description of HSCT recipients with HMs using available data from the national registry, reporting the results for a large cohort to fully characterize risk factors for mortality. Therefore, the strengths of our study include its nationwide scope and its large sample size. We also used a robust methodological approach. By analyzing this centralized administrative database, we captured comprehensive information to depict an overall picture and enhance the generalizability of our findings.

Nonetheless, further research is needed to assess the role of immunological recovery, graft-versus-host disease, other transplant-specific factors, and the biomarkers of immune function that may be associated with mortality due to COVID-19 infection to provide further insight into risk stratification for HSCT recipients.

Conclusions

We characterize the clinical and demographic profiles of the HSCT population among patients with HMs. Our findings provide demographic, clinical, and disease-specific factors that influenced outcomes in HSCT recipients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although mortality in this group is higher than in the general population, the rate is lower than that for non-HSCT recipients, likely due to superior immunological status. Our findings are consistent with previous studies. They demonstrate the increased risks associated with all patients with HMs during the COVID-19 pandemic, even those who underwent an HSCT. The relatively favorable outcomes in HSCT recipients form a contrast with some early reports, but this discrepancy may be due to differences in study design, included population, and pandemic phase. Overall, our findings highlight the need for tailored management strategies and continued vigilance in patients who either have an HM or have undergone HSCT.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available because a contract signed with the Spanish National Health System, which provided the data set, prohibits the authors from providing their data to any other researcher. Furthermore, the authors must destroy the database upon the conclusion of their investigation. The database cannot be uploaded to any public repository. However, they are are available on reasonable request at https://www.sanidad.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/sisInfSanSNS/aplicacionesConsulta/home.htm.

References

Gorbalenya, A. E. et al. The species severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol. 5 (4), 536–544 (2020).

Lovato, A. & de Filippis, C. Clinical presentation of COVID-19: A systematic review focusing on upper airway symptoms. Ear Nose Throat J. 99 (9), 569–576 (2020).

COVID-19 deaths | WHO COVID-19 dashboard. [Internet]. datadot. [cited 2024 Apr 8]. Available from: http://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases

Garcia-Carretero, R., Vazquez-Gomez, O., Lopez-Lomba, M., Gil-Prieto, R. & Gil-de-Miguel, A. Insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome as risk factors for hospitalization in patients with COVID-19: pilot study on the use of machine learning. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 21 (8), 443–452 (2023).

Garcia-Carretero, R., Vazquez-Gomez, O., Rodriguez-Maya, B., Gil-Prieto, R. & Gil-de-Miguel, A. Outcomes of patients living with HIV hospitalized due to COVID-19: A 3-Year nationwide study (2020–2022). AIDS Behav. 28 (9), 3093–3102 (2024).

Garcia-Carretero, R., Ordoñez-Garcia, M., Gil-Prieto, R. & Gil-de-Miguel, A. Outcomes and patterns of evolution of patients with hematological malignancies during the COVID-19 pandemic: A nationwide study (2020–2022). J. Clin. Med. 13 (18), 5400 (2024).

Salmanton-García, J. et al. Decoding the historical tale: COVID-19 impact on haematological malignancy patients-EPICOVIDEHA insights from 2020 to 2022. EClinicalMedicine 71, 102553 (2024).

Chien, K. S. et al. Outcomes of breakthrough COVID-19 infections in patients with hematologic malignancies. Blood Adv. 7 (19), 5691–5697 (2023).

Pagano, L. et al. COVID-19 infection in adult patients with hematological malignancies: a European hematology association survey (EPICOVIDEHA). J. Hematol. Oncol. 14, 168 (2021).

Langerbeins, P. & Hallek, M. COVID-19 in patients with hematologic malignancy. Blood 140 (3), 236–252 (2022).

Vijenthira, A. et al. Outcomes of patients with hematologic malignancies and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 3377 patients. Blood 136 (25), 2881–2892 (2020).

Agrawal, N. et al. Outcomes of COVID-19 in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: multicenter retrospective analysis. Indian J. Hematol. Blood Transfus. 38 (2), 388–393 (2022).

Rosen, E. A. et al. COVID-19 Outcomes Among Hematopoietic Cell Transplant and Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Recipients in the Era of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variants and COVID-19 Therapeutics. Transplantation and Cellular Therapy. ;30(11):1108.e1-1108.e11. (2024).

Sharma, A. et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 in Haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation recipients: an observational cohort study. Lancet Haematol. 8 (3), e185–e193 (2021).

Maurer, K. et al. COVID-19 and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and immune effector cell therapy: a US cancer center experience. Blood Adv. 5 (3), 861–871 (2021).

Ljungman, P. et al. The challenge of COVID-19 and hematopoietic cell transplantation; EBMT recommendations for management of hematopoietic cell transplant recipients, their donors, and patients undergoing CAR T-cell therapy. Bone Marrow Transpl. 55 (11), 2071–2076 (2020).

Strasfeld, L. COVID-19 and HSCT (Hematopoietic stem cell transplant). Best Pract. Res. Clin. Haematol. 35 (3), 101399 (2022).

Shah, G. L. et al. Favorable outcomes of COVID-19 in recipients of hematopoietic cell transplantation. J. Clin. Invest. 130 (12), 6656–6667 (2020).

van Heijst, J. W. J. et al. Quantitative assessment of T-cell repertoire recovery after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Nat. Med. 19 (3), 372–377 (2013).

Grifoni, A. et al. Targets of T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in humans with COVID-19 disease and unexposed individuals. Cell 181 (7), 1489 (2020).

Wang, B. et al. A tertiary center experience of multiple myeloma patients with COVID-19: lessons learned and the path forward. J. Hematol. Oncol. 13, 94 (2020).

Shahzad, M. et al. Impact of COVID-19 in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 24 (2), e13792 (2022).

Ministerio de Sanidad - Profesionales. - Salud pública - Prevención de la salud - Vacunaciones - Programa vacunación - Estrategia de Vacunación COVID-19: Actualizaciones [Internet]. [cited 2023 Oct 17]. Available from: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/promocionPrevencion/vacunaciones/covid19/Actualizaciones_EstrategiaVacunacionCOVID-19.htm

Varma, A. et al. COVID-19 infection in hematopoietic cell transplantation: age, time from transplant and steroids matter. Leukemia 34 (10), 2809–2812 (2020).

Passamonti, F. et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors associated with COVID-19 severity in patients with haematological malignancies in Italy: a retrospective, multicentre, cohort study. Lancet Haematol. 7 (10), e737–e745 (2020).

Gavillet, M., Carr Klappert, J., Spertini, O. & Blum, S. Acute leukemia in the time of COVID-19. Leuk. Res. 92, 106353 (2020).

Funding

This work was supported by AstraZeneca. The funding source had no role in the study design or the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data. AstraZeneca was not involved in the writing of the manuscript. The authors had final responsibility for the decision to submit it for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RGC conceived and designed the study, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and preprocessed and analyzed the data. MOG, MRG and OBP made substantial contributions to the interpretation of the results, critically reviewed the first draft of the manuscript, and made valuable suggestions. RGP and AGM supervised the project and critically reviewed and edited the final draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Garcia-Carretero, R., Ordoñez-Garcia, M., Rodriguez-Gonzalez, M. et al. Nationwide study of COVID-19 outcomes in hematologic patients following bone marrow transplantation. Sci Rep 15, 10506 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95246-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95246-w