Abstract

Blockchain technology has gained significant attention in several sectors owing to its distributed ledger, decentralized nature, and cryptographic security. Despite its potential to reform the healthcare industry by providing a unified and secure system for health records, blockchain adoption remains limited. This study aimed to identify the factors influencing the intention to adopt blockchain in healthcare by focusing on healthcare providers. A theoretical model is proposed by integrating the Technological-Organizational-Environmental framework, Fit-Viability Model, and institutional theory. A quantitative approach was adopted and data were collected through an online survey of 199 hospitals to evaluate the model. The collected data were analysed using PLS-SEM. The results indicated that technology trust, information transparency, disintermediation, cost-effectiveness, top management support, organizational readiness, partner readiness, technology vendor support, fit, and viability significantly and positively influenced the intention to adopt blockchain-based Health Information Systems in hospitals. Conversely, coercive pressure from the government negatively affects adoption decisions. Moreover, the study found that the hospital ownership type did not moderate the relationship between the identified factors and blockchain adoption. This study provides valuable insights into the various factors that influence blockchain adoption in hospitals. The developed model offers guidelines for hospitals, blockchain providers, governments, and policymakers to devise strategies that promote implementation and encourage widespread adoption of blockchain in healthcare organizations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The healthcare sector is fundamental to improving the well-being and economic resilience of nations1. While technological advancements and information systems have revolutionized healthcare delivery, enabling more efficient data management and service provision2, they have also introduced significant challenges. In particular, digitized healthcare information systems (HIS) face growing issues related to data security, privacy, interoperability, and operational inefficiencies3. Centralized data management, a hallmark of many existing HISs, often results in data breaches, unauthorized access, and limited integration between systems, which compromise patient trust and the quality of care4. The COVID-19 pandemic has further emphasised the need for innovative technologies to strengthen healthcare systems, with increased attention to health data privacy5,6,7. These limitations are particularly acute in regions like Malaysia, where hospitals operate without a unified healthcare system, necessitating seamless and secure data sharing to ensure coordinated care8,9,10.

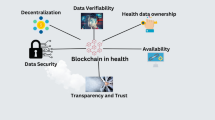

Blockchain technology (BCT) has emerged as a possible solution for healthcare data management challenges11,12. Its decentralized, transparent, and immutable design provides robust data security, privacy, and interoperability, addressing critical gaps in HISs13,14. Moreover, blockchain enables smart contracts that automate workflows, improve operational efficiency, and enhance accountability among healthcare stakeholders15 These capabilities make blockchain particularly suited to tackling the inefficiencies and vulnerabilities in Malaysia’s healthcare data management systems16. For healthcare providers, BCT introduces transparency and accountability, alleviating burdens on physicians, saving time, and improving patient engagement17. Furthermore, adopting BCT reduces wasteful and duplicate tasks, leading to substantial cost savings16,18. It is estimated that implementing BCT in healthcare could save USD 100–150 billion annually by 2025, addressing costs related to data breaches, IT operations, support functions, and fraud19.

Despite its transformative potential, blockchain adoption in Malaysian hospitals remains minimal16,18,20. Less than 10% of Malaysian healthcare organizations have implemented blockchain-based solutions21,22. Underscoring significant barriers such as high implementation costs, lack of standardization, and resistance to change23,24. Data breaches alone have cost Malaysian hospitals millions annually, with studies linking poor interoperability and outdated HISs to increased operational inefficiencies and diminished patient outcomes20,25,26. Recognizing these issues, the Malaysian government has highlighted digital transformation in its Twelfth Malaysia Plan (2021–2025) as a priority to strengthen the healthcare system20. However, systemic challenges and insufficient empirical evidence continue to impede progress18,25. Most blockchain projects in healthcare remain conceptual, as organizations hesitate to adopt this disruptive technology due to its maturity level, risks, and costs24,27,28,29. The transition to a blockchain-based system depends on various internal and external factors, but the literature reveals insufficient focus on understanding these influences, particularly in the context of healthcare providers’ behavioral intentions30,31. The adoption of innovative technology such as BCT involves several stages, with acceptance or rejection as the outcome24,27,28,29. From an organizational perspective, decisions to implement IT/IS innovations require analyses of technological, organizational, and environmental factors, which influence both the usability and viability of the technology32. These factors must be studied holistically to ensure the technology aligns with organizational goals and maximizes IT investments33,34,35.

Existing studies on BCT adoption in healthcare are predominantly literature reviews or conceptual analyses that focus on technical details rather than organizational and environmental determinants (e.g17,36,37,38). While some empirical studies provide valuable insights, they are narrow in scope, often focusing on a single entity or level, such as patients or physicians39, or relying on qualitative approaches (e.g34,40,41). There is a clear gap in research addressing the broader technological, organizational, and environmental influences on blockchain adoption in healthcare24,27,28,29, particularly in Malaysia. Moreover, the literature has yet to examine disparities in adoption between public and private hospitals, which operate under different models, priorities, and resource constraints42. Understanding these differences is vital for identifying drivers and barriers to BCT adoption and tailoring strategies to the unique needs of healthcare providers43,44,45.

To bridge these gaps, this study employs the Technology-Organization-Environment (TOE) framework, the Fit Viability Model (FVM), and institutional theory to investigate the organizational and external factors influencing blockchain adoption in Malaysian hospitals. Specifically, this research seeks to answer the following key question:

-

What factors influence the intention to adopt blockchain technology-based healthcare information systems in Malaysian hospitals?

A quantitative research approach was undertaken, targeting top- and mid-level managers in public and private Malaysian hospitals to explore the technological, organizational, and environmental determinants of blockchain adoption. By comparing adoption drivers between public and private hospitals, this study provides actionable insights for policymakers, hospital administrators, and other stakeholders. The findings aim to guide the development of effective strategies for promoting blockchain adoption, thereby enhancing data security, operational efficiency, and the overall sustainability of Malaysia’s healthcare system.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Sect. 2 reviews the relevant literature; Sect. 3 introduces the research model and hypotheses; Sect. 4 outlines the methodology; Sect. 5 presents the results and analysis. Section 6 discusses the findings, highlights theoretical and practical contributions, addresses limitations, and proposes future research directions. Finally, Sect. 7 concludes the paper.

Literature review

Related work

Blockchain technology (BCT) has garnered attention in healthcare as a transformative tool to address challenges in data security, interoperability, and operational efficiency. However, despite its potential, empirical studies examining BCT adoption in healthcare at the organizational level remain limited11,46,47.

Existing studies have primarily focused on identifying barriers and enablers of BCT adoption through qualitative and descriptive approaches. For instance, research in India using workshops and interviews highlighted regulatory issues, high costs, lack of expertise, and limited trust as critical barriers to adoption, emphasizing the need for better awareness and regulatory frameworks40. Similar findings were reported in South Korea, where concerns about cooperation, data standardization, and utilization were observed despite recognizing BCT’s potential benefits, such as security and interoperability48.

Consumer perspectives have also been explored. In Canada, focus groups revealed concerns about private key management, care accessibility, and data irrevocability, suggesting that design enhancements like private key recovery and trusted health wallet hosts could improve adoption49. Quantitative studies in Korea and Thailand identified a gap between patient optimism and healthcare professionals’ awareness, underscoring the need for targeted education and training for physicians39,50.

Other studies have examined specific use cases, such as blockchain-based personal health records (PHRs) and health information exchanges (HIEs). These studies highlight benefits such as transparency, traceability, and real-time data processing but also point to challenges, including organizational and technological risks, trust deficits, and market uncertainties34,36,51.

Despite these efforts, literature reveals significant gaps. Most studies focus on individual-level factors, such as patient or physician perspectives, neglecting the organizational and environmental dimensions of adoption. The healthcare industry’s institutionalized nature necessitates examining institutional pressures and their influence on BCT adoption decisions, which remains underexplored43,44,45, Moreover, economic considerations, such as cost-effectiveness and financial sustainability, have received minimal attention.

Critically, the existing literature lacks comprehensive theoretical models grounded in well-established technology adoption frameworks. While some studies reference technical, organizational, and environmental factors, they fail to examine how these interact holistically in the context of healthcare organizations. Furthermore, research seldom addresses decision-makers’ perspectives in hospitals, where adoption decisions are primarily made, leaving a gap in understanding the institutional and managerial dynamics of BCT implementation.

This study addresses these gaps by developing an integrated research model that combines the Technology-Organization-Environment framework, the Fit Viability Model, and institutional theory. By examining technological, organizational, and environmental factors alongside institutional pressures, the model provides a comprehensive lens to analyze BCT adoption in hospitals. Additionally, the study uniquely considers the differences between public and private hospitals, offering valuable insights into how distinct operational models influence adoption. This approach advances the literature by providing empirical evidence on the determinants of BCT adoption, supporting the development of evidence-based strategies for blockchain implementation in healthcare.

Adoption models and theories

Organizational adoption refers to the implementation of innovations into organizational practices52. Various theoretical models, such as the Technology-Organization-Environment (TOE) framework, the Fit-Viability Model (FVM), and Institutional Theory (INS), have been widely used to explore the factors influencing technology adoption decisions.

The TOE framework, introduced by Tornatzky et al.53 offers a comprehensive lens to analyze technology adoption by considering three dimensions: technological, organizational, and environmental. The technological dimension focuses on the features of the technology and its current level of use within the organization. The organizational dimension examines the size, structure, resources, and management systems of the organization, while the environmental dimension addresses external influences, such as regulatory pressures, trade partnerships, and market competition. This framework has been extensively applied across sectors, including supply chain54,55, construction56, retail market57, energy management58, automotive59, elderly care60, manufacturers61, and libraries62. to analyze adoption dynamics.

The FVM, initially developed to evaluate internet initiatives in organizations63. later expanded to assess new technologies more broadly64. This model focuses on two key components: fit and viability. Fit evaluates how well a technology aligns with the needs, goals, and processes of an organization, while viability examines whether the organization has the resources and capabilities necessary for successful adoption. By addressing both alignment and feasibility, the FVM helps organizations predict potential risks and make informed decisions. The model has been applied in areas such e-government implementation65, e-learning66, media advertising67, and healthcare68. providing a valuable framework for understanding the suitability and practicality of new technologies.

Institutional Theory (INS), introduced by DiMaggio and Powell69, examines the influence of external pressures on organizational behavior. INS identifies three mechanisms of institutional isomorphism: mimetic, coercive, and normative pressures. Mimetic pressures arise from competition, driving organizations to emulate successful peers. Coercive pressures are often regulatory, compelling organizations to comply with laws and standards. Normative pressures stem from professional norms and expectations. In the healthcare sector, these institutional forces shape the adoption of innovations like health information systems, with decisions influenced by stakeholders such as competitors, governments, and business partners43,70,71,72.

These theories have complementary strengths: while TOE provides a broad framework for assessing internal and external factors, FVM focuses on detailed evaluations of fit and viability, and INS highlights the socio-institutional influences that extend beyond organizational boundaries. However, each model has limitations. TOE may overlook deeper contextual and institutional forces, FVM focuses primarily on organizational readiness and may not fully account for external pressures, and INS does not emphasize the specific technological attributes that affect adoption.

The integration of TOE, FVM, and INS offers a novel and comprehensive approach to understanding BCT adoption in healthcare. By combining these theories, this study captures the technological, organizational, and environmental determinants (TOE), evaluates their alignment with organizational goals and resources (FVM), and accounts for the impact of external institutional pressures (INS). Together, these models create a robust framework for analyzing the adoption of BCT-based health information systems (HIS) in Malaysian hospitals. This integrated perspective enables a nuanced understanding of adoption dynamics, helping stakeholders navigate the complexities of implementing innovative technologies in healthcare environments. This integration not only enhances the explanatory power of the structural model but also adds novelty by addressing the limitations of prior studies and offering actionable insights into the adoption of BCT-based health information systems in Malaysian hospitals.

Research model and hypothesis

An extensive review of previous studies on BCT adoption was conducted to identify the constructs for the proposed integrative research model. This review underscores the diverse range of factors examined in prior research across various sectors. A rigorous process of collaboration, matching, filtering, and consolidation was employed to ensure a comprehensive and inclusive list of factors identified in the literature. Each construct was carefully scrutinized for its relevance and applicability to BCT adoption in the healthcare sector.

Table 1 presents a mapping matrix summarizing the constructs used in this study, alongside their application in previous studies of BCT adoption across different industries. These studies employed diverse theoretical frameworks, including the TOE framework, INS, and FVM, among others. Key constructs such as technological, organizational, and environmental factors emerged as critical determinants of BCT adoption. The matrix highlights the variation in theoretical focus and contextual application across studies, reflecting the evolution of research on BCT adoption.

A critical analysis of the mapping matrix reveals notable trends and gaps. While several studies have examined individual sectors or employed singular theoretical frameworks, limited research has adopted a comprehensive, multi-perspective approach. Furthermore, healthcare-specific factors remain underexplored, despite the sector’s inherent complexity and distinct requirements.

Building on these insights, this study proposes a novel integrative model for the adoption of blockchain technology-based Health Information Systems (BCT-HIS). The model incorporates the constructs identified in Table 1 and has been validated through expert reviews involving 15 individuals with expertise in academia, technology, and healthcare in Malaysia. This validation process confirmed the relevance and significance of these constructs in predicting BCT-HIS adoption, thereby enhancing the model’s credibility and robustness.

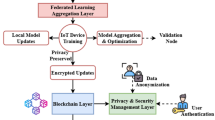

The proposed model is illustrated in Fig. 1 and represents an innovative integration of the TOE framework, INS Theory, and FVM. Unlike prior studies that typically focused on a single theoretical perspective, this study’s integrative approach offers a holistic view of the factors influencing BCT adoption in healthcare. The model uniquely emphasizes the interplay between technological factors (technology trust, transparency, disintermediation, and cost-effectiveness) and technological fit, organizational factors (organization readiness, top management support, and corporate social responsibility), and environmental factors (mimetic pressure, coercive pressure, vendor support, and partner readiness) and viability. It also introduces hospital type (public vs. private) as a moderating variable, addressing the contextual diversity within the healthcare sector.

Technology trust (TT)

Technology trust refers to the belief in a particular technology’s reliability, security, and effectiveness90. Individuals and organizations are more likely to adopt the technology they trust91. A BCT’s technical trust is considered more reliable than traditional institutional trust, particularly when data privacy and access control are critical92. BCT provides transparency, accountability, and security through cryptographic technology, making it suitable for integration into HIS93. Previous research has shown that trust in BCT positively influences its adoption in healthcare50 and various domains, such as accounting87, supply chain54,89,94, SME95, and elderly care60. Technology trust has been shown to play a critical role in shaping perceptions of technology-fit. Studies have demonstrated that higher levels of trust in a technology system enhance its perceived compatibility with organizational processes and goals60. For example, trust in blockchain systems ensures reliability, security, and data integrity, which directly contributes to its fit within healthcare technology infrastructure50. Therefore, we hypothesize as follows:

H1

Technology trust has a significant impact on technology-fit.

Information transparency (TRAN)

Information transparency refers to the accessibility, understandability, and availability of information to relevant stakeholders96. In healthcare, information transparency is essential for stakeholders to find and verify information in a blockchain system97. BCT enables transparency by creating a decentralized and distributed data infrastructure where transactions are secure and visible to all participants, which reduces information asymmetry and improves traceability, fostering a transparent atmosphere for healthcare decision making86. Information transparency directly influences the perception of technology-fit by enhancing openness and reducing ambiguity in technology systems. Research indicates that transparent systems foster a clear understanding of data flows, promoting better alignment with organizational needs and processes58,73,98,99. The direct link between information transparency and technology-fit has been validated across various technological domains, including blockchain in healthcare24,100. Therefore, we hypothesize as follows:

H 2: Information Transparency has a significant impact on technology-fit.

Perceived disintermediation (DIS)

Perceived disintermediation refers to the belief that a BCT can eliminate or reduce the need for intermediaries in transactions and interactions101. Perceived disintermediation is a key factor influencing technology-fit, as it reduces reliance on intermediaries and streamlines processes. Studies highlight that systems enabling direct transactions and eliminating middlemen are perceived as more adaptable to organizational workflows, thereby improving their fit with existing technological contexts73,102,103. When hospitals perceive that they can operate their businesses without relying on intermediaries, they are more likely to adopt BCT. This adoption is driven by blockchain’s potential to minimize intermediaries’ involvement in healthcare transactions, resulting in cost reduction and faster processing101 Thus, it can be hypothesized that.

H3: Perceived Disintermediation has a significant impact on technology fit.

Cost-effectiveness (COEF)

Cost-effectiveness refers to the concept that the benefits of adopting a new technology outweigh the initial costs of implementation104. In the context of BCT-based HIS, an initial investment is required for acquisition105. Cost-effectiveness directly impacts technology-fit by influencing decision-makers’ perceptions of the economic value of adopting BCT83. Research shows that when a technology demonstrates clear cost savings and financial benefits, it is considered better aligned with organizational resources and goals, thus enhancing its fit106,107. However, studies have shown that BCT has the potential to save the healthcare industry billions of dollars annually by reducing the costs associated with data breaches, IT expenses, operations, fraud, and more19. These cost reductions can be achieved through automation108, avoidance of costly errors109, removal of intermediaries110, record duplication reduction111, and data collection time and effort reduction112. The cost-effectiveness of a BCT-based HIS lies in its ability to deliver faster and more accurate results while saving time and money113. Thus, it can be hypothesized that:

H 4: Cost-effectiveness has a significant impact on technology-fit.

Technology-fit (FIT)

Technology fit refers to the compatibility between a technology and an organization’s existing systems, processes, and requirements114. In this study, blockchain fitness refers to how well its unique characteristics and capabilities align with a healthcare organization’s specific needs and requirements, particularly in managing and securing health information. A good fit between a BCT and a hospital’s information management system can lead to various benefits, including improved data integrity, enhanced security, streamlined interoperability, increased efficiency, and reduced costs31. These advantages positively influence a hospital’s intention to adopt BCT-based HIS. Previous research has shown a positive relationship between technology fit and intention to adopt technology in various contexts31,115. As a result, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H 5: Technology-fit has a significant impact on the intention to adopt blockchain-based HIS.

Top management support (TMS)

Top Management Support refers to the degree of commitment and active support from top managers toward a new initiative or change31. In the context of a BCT-based HIS, TMS refers to the level of understanding and willingness of top managers in healthcare organizations to contribute to the adoption of BCT. Top management support has a direct and significant impact on the viability of new technology adoption. Leaders who actively support and allocate resources toward technology adoption create an environment conducive to successful implementation, increasing the perceived viability of the technology74,80. Support from top managers involves their expertise and practical experience with healthcare information technology as well as the deployment of necessary resources for adoption. Previous studies have highlighted the importance of TMS in the adoption of BCT in various industries, such as SME73, supply chains74,79,80,82,84, libraries62, construction56, financial85, and elderly care60. As a result, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H 6: Top management support has a significant influence on viability.

Organizational readiness (OR)

Organizational Readiness refers to an organization’s preparedness to undertake new initiatives or changes116. An organization’s capability to embrace and integrate new technologies is encompassed by organizational readiness. Several factors, including the organization’s ability to allocate financial and technological resources such as physical IT infrastructure, human resources with technical and managerial IT skills, and intangible resources such as knowledge and culture, influence organizational readiness117,118. Therefore, organizational readiness, including the required infrastructure and IT expertise, is critical to effectively adopting new technologies119. Studies have shown that organizational readiness positively influences firms’ willingness to adopt eHealth solutions120, while organizations lacking adequate technological, human, and financial resources are unlikely to adopt new technologies121. Organizational readiness is a critical determinant of viability, as it reflects the preparedness of resources, infrastructure, and skills. Studies indicate that higher levels of readiness improve stakeholders’ confidence in the feasibility and practicality of adopting in different sectors such as supply chain54,80,82,89, elderly care60, finance85, construction88, and healthcare112. As a result, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H 7: Organizational Readiness has a significant influence on viability.

Corporate social responsibility (CSR)

Corporate Social Responsibility refers to an organization’s responsibility to consider its operations’ social, environmental, and economic impacts122. In hospitals, CSR involves ethical and socially responsible practices that benefit the communities, patients, and environment123. This encompasses a range of activities undertaken by hospitals to contribute to the well-being of these stakeholders124. CSR initiatives directly contribute to the perceived viability of new technology adoption125. Organizations with strong CSR practices are more likely to adopt technologies that align with their social and ethical commitments, enhancing their viability in the organizational context126. Organizations that actively engage in CSR in the healthcare sector are more likely to support technological innovations such as BCT-based HIS. This support is driven by the need to ensure the security and privacy of patient information and to provide more effective services127,128. CSR was recognized as a critical organizational factor influencing viability of BCT adoption60. Therefore, we hypothesize as follows:

H 8: Corporate Social Responsibility has a significant influence on viability.

Mimetic pressure - competitors (COM)

Mimetic pressure from competitors refers to the tendency of organizations to imitate the activities and behaviours of their competitors in the same industry69. According to institutional theory, organizations must emulate their peers to avoid falling behind or experiencing economic loss129. Mimetic pressure from competitors significantly impacts the perceived viability of technology adoption, especially when facing the demands of healthcare stakeholders and new healthcare models43. Therefore, hospitals may adopt a BCT-based HIS to attract new patients and gain a competitive advantage. Organizations often follow industry leaders and competitors in adopting innovative technologies, which fosters confidence in their feasibility and potential success88. The literature on BCT adoption in accounting87, supply chain74,84,89,130, construction88, banking86, and manufacturing61 states that mimetic pressure from competitors catalyses an organization’s decision to adopt BCT. Thus, we hypothesize as follows:

H 9: Mimetic pressure from competitors has a significant influence on viability.

Coercive pressure- government (GOV)

Coercive pressure from the government refers to regulations, incentives, subsidies, and infrastructure support imposed by government entities to pressure the healthcare sector to adopt new technologies69. Governmental incentives, particularly regarding infrastructure, collaboration, and risk management, are critical for technology adoption24,33,131. Studies have shown that government pressure significantly accelerates BCT adoption58,132. The significant impacts of government support and regulations on viability of BCT adoption have been observed in sectors such as supply chain management84,85,89,130, banking86, accounting87, and construction88. In the healthcare sector, where organizations are predominantly public or private institutions regulated by the government, coercive pressure from the government in the form of supportive regulations, funding for research and development, infrastructure support, and incentives can significantly influence the viability of blockchain adoption24,34,40,41,60,133. Therefore, we hypothesize as follows:

H 10: Coercive pressure from the government has a significant influence on viability.

Partner readiness (PR)

The readiness of an organization’s partners to embrace new technologies is referred to as partner readiness134. Partner readiness for blockchain adoption in hospitals is crucial because it relies on interoperability and stakeholder collaboration to maximize its benefits135. Partners in blockchain networks must work together and interact effectively. It is not feasible for an organization to unilaterally deploy BCT if its trading partners lack the necessary technical and financial resources135,136. Partner readiness is directly linked to the viability of technology adoption. The significance of partner readiness lies in the collaborative nature of the blockchain technology86. Hospitals can adopt BCT only when their trading partners are ready. Attempting to adopt blockchain without the cooperation and willingness of trading partners may lead to unfavourable outcomes137. Studies show that when partners and stakeholders demonstrate preparedness and willingness to collaborate, organizations are more likely to perceive the technology as viable for BCT implementation in various sectors such as supply chain management136 and SEM73. Thus, we hypothesize as follows:

H 11: Partner readiness has a significant influence on viability.

Technology vendor support (TVS)

Technology Vendor Support (TVS) refers to the assistance and resources technology vendors provide to their customers to implement, maintain, and troubleshoot their products or services138. The support provided by technology vendors plays a critical role in facilitating the adoption of new technology78. They offer technical assistance, training, and incentives to help organizations adopt and utilize new technologies139. In the healthcare sector, IT service providers and vendors significantly influence the decision to use new technology services140. Technology vendor support plays a critical role in determining the viability of technology adoption in healthcare43. Given BCT’s complexity and novelty, vendor assistance availability becomes an important consideration when deciding whether to implement it141. Strong vendor support ensures smooth implementation, technical assistance, and system maintenance, which directly influences the perceived feasibility of the technology in healthcare organizations43,106,142. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H 12: Technology vendor support has a significant influence on viability.

Viability (VIB)

The practical usefulness of a technology in an organization and its impact on the intention to adopt it are determined by viability, which encompasses the influence of organizational and national factors on the decision to adopt a system180. Viability is also affected by an organization’s infrastructure readiness for implementation90,94,181,182. The viability of deploying BCT is determined by various factors, including organizational and environmental constraints111. It considers the readiness of the healthcare organization for BCT and the potential value it adds to adopting a BCT-based HIS. When healthcare organizations perceive BCT as viable, they are more likely to express their intention to implement it. Previous studies have found a strong relationship between viability and intention to adopt technology44,110. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H 13: Viability has a significant impact on the intention to adopt blockchain-based HIS.

Moderating variable: hospital type (public or private)

This study examines hospital ownership type—public or private—as a moderating variable in the adoption of blockchain-based health information systems (BCT-based HIS). Ownership type significantly influences organizational decision-making processes due to inherent structural and operational differences. Public and private hospitals operate under distinct frameworks, with variations in governance, resource allocation, organizational priorities, and decision-making processes. These differences shape how hospitals perceive and respond to factors influencing blockchain adoption, making hospital type a crucial moderator in the model.

Public hospitals are typically characterized by higher levels of regulatory oversight, bureaucratic procedures, and resource constraints, which often result in slower technology adoption143,144. In contrast, private hospitals, driven by profit motives and competitive pressures, tend to have more autonomy, streamlined decision-making processes, and greater financial flexibility, enabling quicker adoption of innovative technologies145.

Differences in goals, such as prioritizing patient care versus profitability, also affect technology adoption. Public hospitals may focus more on accessibility and equity, while private hospitals often emphasize efficiency and service quality146,147,148. These divergent priorities influence the weight placed on various factors, such as cost-effectiveness, technology trust, and vendor support, when deciding to implement new systems.

Moreover, previous studies (e.g146,147,148.) have documented varying responses to technology adoption across public and private healthcare organizations due to differences in organizational readiness, managerial support, and external pressures. These distinctions suggest that ownership type moderates the relationships between technological, organizational, and environmental factors and the adoption of BCT-based HIS.

Given these insights, this study hypothesizes that the moderating effect of hospital type will manifest in differential impacts of the identified factors on blockchain adoption. By considering this moderating effect, the study provides a nuanced understanding of how different hospital types navigate the challenges and opportunities of blockchain adoption. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H 14: Hospital type (public or private) moderates the relationships in the model.

Methodology

Research instrument

For this research, a positivist research approach was chosen due to its emphasis on quantitative data, which allows for the efficient measurement of responses on a large scale across hospitals in Malaysia. A preliminary survey was conducted to gather data and assess the validity of the proposed research model. The questionnaire was considered an appropriate tool for conducting in-depth investigations of variable relationships and hypotheses testing149. In addition, the survey allowed researchers to gauge the attitudes and decisions of respondents regarding the phenomenon150. To measure the 14 reflective constructs in the developed model, the researchers used 66 indicators drawn from previous studies. These indicators were adapted and modified to align with the specific context of this study. The measurements of the items are presented in Table 2.

The questionnaire used in this study consists of two sections. The first encompassed demographic information about the respondents and their respective hospitals, including gender, age, position, experience, and hospital type. The second section involved 66 questions that measured the 14 constructs of the research model. Respondents selected their level of agreement or disagreement with each statement on a five-point Likert scale (“1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly Agree”). The Likert scale is recommended as a practical design choice for collecting data through self-administered or online survey methods151. Additionally, in social science research, including that conducted in healthcare, the five-point Likert scale is a well-known and widely used measurement tool for assessing attitudes, opinions, and perceptions152.

Expert evaluation, which is a commonly accepted approach, was employed as a critical method to enhance the content validity of the questionnaire152. In this study, a panel of five expert researchers specializing in IS from various universities critically reviewed the instrument. Each researcher provided valuable suggestions and feedback to enhance the instrument’s quality and alignment with its research objectives. Modifications and enhancements to the questionnaire were made based on valuable feedback provided by the experts.

The research instrument was assessed through a pilot study involving 20 hospitals that were not part of the main survey. The findings from this pilot study offer compelling evidence to support the reliability and validity of the scales used in the research instrument.

Population and sampling

This study focused on examining the factors that impact Malaysian hospitals’ intention to adopt BCT. The unit of analysis was organizations, specifically Malaysian hospitals, whereas the unit of observation consisted of senior management and IT professionals. These individuals were chosen because they are typically knowledgeable about the organization’s strategies and decisions, including the adoption of new technologies in Malaysian hospitals43. The target population included public and private hospitals in Malaysia. According to the Ministry of Health, Malaysia157, there were 357 hospitals, 146 public hospitals, and 209 private hospitals. Based on the Krejcie and Morgan158 guidelines, a sample size of 186 hospitals was deemed appropriate for this study, considering a population size of 357 hospitals.

Given the heterogeneity of the target population, a disproportionately stratified random sampling technique was used159. Stratification involves dividing a population into homogeneous subgroups, called strata. Each stratum was represented by a random sample and the sample size was not necessarily proportional to the stratum size. This approach helps to mitigate selection bias and sample variance, leading to more generalizable results. This study used hospital type (public or private) as a stratification variable. The hospitals were randomly selected from each stratum list. The sampling frame consisted of two sources of hospital data: the official website of the Ministry of Health in Malaysia for public hospitals and the website of “The Association of Private Hospitals Malaysia” (APHM) for private hospitals. The contact information for all hospitals included in the sampling frame was obtained from each hospital’s official website.

Data collection

Due to the targeted hospitals distributed in 13 geographical states in Malaysia, the online questionnaire survey approach was considered the most suitable for collecting the required data to examine Malaysian hospitals’ adoption of BCT-based HIS. Online surveys are among the current types of questionnaire surveys. This type of survey is low-cost to organize, results are immediately well documented in an online database, and modification of the survey can be done if required160,161. The survey link to the questionnaire was sent by email to the target hospitals and included a cover letter, research objectives, instructions, and questionnaire. In addition, the average completion time of the survey was provided and a confidentiality statement was made. To ensure precise data collection, each organization was instructed to distribute the survey to individuals holding key positions within their hierarchy, including CEO, CTO, and IT directors/managers.

A set of 295 questionnaires were distributed via email to both public and private hospitals throughout Malaysia, with 199 questionnaires ultimately returned and utilized for data analysis. The response rate was 67.45%, which is considered reasonable for an email survey162. Data were collected between January 2023 and June 2023. Table 3 presents the demographic data of the sample regarding gender, age, position, experience, and hospital type.

Data analysis tools

Partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) using SmartPLS 4.0 was used to comprehensively analyse the survey data for hypothesis testing and model evaluation. PLS-SEM is widely recognized and preferred owing to its exceptional capabilities in quantitative data analysis163. Both PLS-SEM and CB-SEM are valuable tools for structural equation modeling, but PLS-SEM is more suitable for this study for several reasons. First, the exploratory nature of this research, which aims to explore relationships and develop a predictive model for blockchain adoption in healthcare, aligns better with PLS-SEM, as it is designed for predictive and exploratory studies. In contrast, CB-SEM is typically used for theory testing and confirmatory research164. Second, the complexity of the model, which includes 14 variables and complex relationships, including moderating effects, makes PLS-SEM more appropriate, as it can efficiently handle such complexity and deliver reliable results even with small to medium sample sizes163. Third, the study’s sample size of 199 hospitals is more suitable for PLS-SEM, which can generate robust results with smaller datasets, whereas CB-SEM requires larger sample sizes for stable parameter estimation hair. Finally, the study’s focus on identifying key factors influencing blockchain adoption and predicting behavioral outcomes fits well with PLS-SEM’s strengths163. PLS-SEM is a two-step process that allows for the systematic evaluation of the proposed model. The assessment of the measurement model is the first step in effectively measuring the latent variables, followed by structural model assessment, which evaluates the hypotheses based on path analysis.

Analysis and results

Common method bias

Respondents introducing data on both dependent and independent variables from the same source created a systematic bias known as the Common Method Bias (CMB)165. Harman’s single-factor test166 was conducted to investigate the presence of CMB in this study’s data set. The results revealed that a single factor accounted for the maximum variance of 0.2945. Based on this finding, it can be concluded that the dataset used in this study did not suffer from CMB because the variance explained by a single factor was approximately 29.45%, which is below the threshold value of 50%. Furthermore, a full collinearity test was performed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). It assesses the potential presence of pathological collinearity, with a VIF exceeding the threshold of 3.3, indicating its existence and potentially suggesting the presence of CMB within the model167. Table 4 shows that the indicators had VIF values below 3.3, indicating that the model is free of CMB.

Measurement model assessment

The assessment of the measurement model includes the scrutiny of reliability (internal consistency and indicator reliability) and validity (convergent and discriminant validity)168. Composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha are commonly used to assess internal consistency. Composite reliability gauges how well indicators measure the underlying construct, whereas Cronbach’s alpha evaluates the extent to which all items measure the same construct. The reliability measures ranged from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater reliability. In exploratory research, values between 0.60 and 0.70 are considered acceptable, while values surpassing 0.70 are deemed satisfactory168. Table 4 reveals that all constructs exhibited satisfactory levels of internal consistency, with composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.835 to 0.927 and 0.736–0.906, respectively.

Indicator reliability, as assessed by outer loading, measures the degree to which an indicator or item in a latent-variable model is related to the underlying construct it is intended to measure168. According to established guidelines, standardized outer loadings in latent-variable models should ideally be 0.708 or higher. In such cases, researchers may remove indicators with an outer loading between 0.40 and 0.70, although this decision should be made judiciously. Indicators should be evaluated for potential removal from a scale if their exclusion is expected to improve AVE beyond the designated threshold value. Indicators with very low outer loadings (< 0.40) were permanently removed from the scale169,170. As shown in Table 4, the outer loadings of all indicators were well above the threshold value of 0.7, except for three items between 0.4 and 0.7. These items included one item of Technology-Fit FIT3 (factor loading 0.550), one item of organizational readiness OR4 (factor loading 0.672), and one item of top management support TMS4 (factor loading 0.634). However, despite loadings below the threshold, these three indicators were not eliminated from the final model, because doing so would not affect the AVE for that construct.

Convergent validity is typically assessed by examining the degree to which a construct’s AVE exceeds a certain threshold (typically above 0.5)168. As Table 4, the AVE values for the constructs ranged from 0.549 to 0.695, indicating that the measures used to assess these constructs confirmed convergent validity.

Discriminant validity assesses the extent to which the different measures of separate constructs are unrelated170. Two critical methods were employed to evaluate discriminant validity: the Fornell-Larcker criterion and the heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT)168. The Fornell-Larcker criterion compares the square root of the AVE for each construct with the correlations between the constructs, ensuring that the former exceeds the latter171.

Table 5 illustrates that in every instance, the square root of the AVE for each construct surpasses its highest correlation with any other construct. Furthermore, the correlations among all latent variables indicated their distinctiveness. Thus, the findings confirm the strong discriminant validity of the measures employed to assess each construct. The HTMT, developed by172, is computed as the average value of the indicator correlations across constructs, relative to the geometric mean of the average correlations of indicators measuring the same construct. An HTMT value exceeding 0.90 suggests a potential issue with discriminant validity. However, for more distinct constructs, a threshold of 0.85 should be considered168. According to the data presented in Table 6, all the HTMT values fell below the threshold of 0.85. Therefore, the model fulfilled reliability and validity criteria.

Structural model assessment

The evaluation of the structural model included several key steps to ensure the robustness and validity of the results. First, collinearity among the constructs was examined using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) to detect potential multicollinearity issues. Next, the significance and relevance of the path coefficients were tested to evaluate the proposed hypotheses and determine the strength and direction of the relationships between constructs. Finally, the model’s explanatory power was assessed to measure its ability to explain the variance in the dependent variables, while its predictive power was evaluated to determine how well the model could predict outcomes in new or unseen data173,174.

Multicollinearity is a potential issue in both reflective and formative types of structural models, and it can lead to reliability problems and difficulties in assessing the relative importance of the independent variables167. To address this concern, researchers usually examine the VIF values for all predictor constructs within the structural model. The results of this study indicated that all VIF values for the inner model remained below the threshold of 5. Thus, collinearity is not a significant concern in the analysis169,170.

Hypotheses testing

Path coefficients (beta) and their associated statistical significance values (t-values) were analysed using bootstrapping with a set of 5000 sub-samples automatically created from the dataset to test the hypotheses. The results are shown in Fig. 2; Table 6.

As shown in Table 7, technology trust, information transparency, perceived disintermediation, and cost-effectiveness exhibited significant positive relationships with the fit of BCT to HIS needs in Malaysian hospitals. The path coefficients for these relationships are 0.192, 0.176, 0.151, and 0.461, respectively. Furthermore, Top management support, Organizational Readiness, Partner readiness, and Technology Vendor support exhibited significant positive relationships with the viability of BCT adoption in Malaysian hospitals. The path coefficients for these hypotheses are 0.193, 0.128, 0.308, and 0.378, respectively. Moreover, coercive pressure from the government had a significantly negative relationship with the viability of BCT adoption in Malaysian hospitals. The path coefficient for this hypothesis was − 0.139. However, corporate social responsibility and mimetic pressure from competitors exhibited weak, non-significant effects on the viability of BCT adoption in Malaysian hospitals. The path coefficients for these hypotheses are 0.102 and 0.001, respectively. Lastly, technology fit and viability exhibited a significant positive relationship with adopting a BCT-based HIS in hospitals, with path coefficients of 0.596 and 0.199, respectively.

Additionally, bootstrapping multigroup PLS analysis aimed to investigate how hospital type (public vs. private) moderates the relationships between constructs in the structural model. Table 8 shows that there were no statistically significant differences in the path coefficients between public and private hospitals across all paths. These results indicate the absence of a moderating effect of hospital type on the relationship between the variables and the adoption of a BCT-based HIS. Therefore, Hypothesis 14 is not supported.

Explanatory and predictive power

The coefficient of determination (R2) indicates the proportion of variance in the endogenous variable that can be explained by the exogenous variables in the model168. A high R2 value indicates a greater degree of explanatory power, and values above 0.75, 0.50, and 0.25 can be considered substantial, moderate, and weak, respectively168. As shown in Table 9, the R2 values for the three endogenous variables, technology fit, viability, and intention to adopt BCT are 0.580, 0.602, and 0.507, respectively, indicating moderate explanatory power. An R2 value of 0.580 for technology fit indicates that technology trust, information transparency, disintermediation, and cost-effectiveness explain 58% of the variance in technology fit. Organizational readiness, top management support, corporate social responsibility, mimetic pressure from competitors, coercive pressure from the government, technology vendor support, and partner readiness explain approximately 60.2% of the total variance in viability. Technology fit and viability explain about 50.7% of the total variance in the intention to adopt blockchain.

Effect size (f2) measures how well a given construct explains a subset of endogenous latent variables. When an exogenous construct is removed from the model, the f2 effect size indicates whether the endogenous construct is significantly affected169,170. According to175, effect size values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 represent the predictive variables’ small, medium, and large effects, respectively. As shown in Table 9, regarding the predictors of technology fit, cost-effectiveness had the largest effect size (f2 = 0.357), while information transparency (f2 = 0.037), disintermediation (f2 = 0.032), and technology trust (f2 = 0.067) had a small effect on technology fit. Analysing predictors of viability shows that technology vendor support (0.216) has a medium effect, while partner readiness (f2 = 0.124), top management support (f2 = 0.038), organizational readiness (f2 = 0.031), and coercive pressure from the government (f2 = 0.032) have small effects. On the contrary, corporate social responsibility and mimetic pressure from competitors have no effect (f2 < 0.02 (f2 = 0.011, and f2 = 0.000, respectively). The effect size of technology fit on the intention to adopt BCT was large at 0.560, while the effect size of viability on the intention to adopt BCT was small at 0.063.

Predictive Relevance (Q2) is a statistical method used to evaluate the predictive power of a structural model168. It measures the accuracy of the model’s predictions by estimating how well it can predict the values of endogenous constructs that are not used in the model estimation process169,170. The Q2 value is obtained using the prediction technique in smart-PLS analysis and is typically reported for each endogenous construct in the model168. A Q2 value of zero indicates that the model has no predictive relevance, whereas a Q2 value greater than zero indicates that the model has some predictive power. The higher the Q2 value, the better the predictive relevance of the model170. As shown in Table 9, the Q2 prediction values for technology fit, viability, and intention to adopt the BCT were 0.555, 0.569, and 0.512, respectively. These values indicate that the structural model has a strong predictive relevance for all three endogenous constructs, as all Q2 prediction values are greater than zero.

Discussion

Discussion of key findings

This study aimed to develop and empirically test a model to provide insight into the factors that influence blockchain-based hospital information system (BCT-based HIS) adoption in Malaysian hospitals. The findings of H1 show that technology trust significantly impacts the fitness of BCT to meet HIS needs. This finding is consistent with the idea that technology trust is critical for the adoption and successful implementation of new technologies, particularly in healthcare, where patient safety and privacy are paramount176. Technology trust is considered a substantial factor in reducing feelings of insecurity that assures adoption intention toward BCT in healthcare24. This result is consistent with previous research that has examined the role of trust in the successful implementation and adoption of BCT in various contexts60,94,177,178. BCT has created a trustworthy environment in healthcare networks36,179. Thus, technology providers and policymakers seeking to promote the adoption and use of blockchain in healthcare settings should focus on building trust in technology among potential users.

The result of H2 indicates that information transparency positively impacts the fit of BCT to HIS needs in Malaysian hospitals. This finding is consistent with previous research stating that information transparency is essential for adopting BCT in healthcare24. In addition, this finding is in line with previous studies that state that transparency has a significant impact on BCT adoption in other sectors73,98,99. Prior studies have shown that transparency is an important characteristic of BCT that can enhance trust, improve the efficiency and effectiveness of healthcare systems, and ultimately contribute to their adoption100,180. The positive relationship between information transparency and the fitness of BCT to HIS needs can be explained by the fact that information transparency can increase perceptions of the reliability and accuracy of healthcare information stored in the blockchain181. Transparency of personal healthcare data is crucial for fostering a robust relationship within the healthcare system and facilitating technology adoption24.

The result of H3 indicates that perceived disintermediation positively impacts the fitness of blockchain to meet HIS needs in Malaysian hospitals. This result supports the findings of73, who found that perceived disintermediation is a significant predictor of the adoption of BCT in SMEs. Hospitals exhibit an attraction toward adopting BCT when they perceive the potential to operate their businesses without the involvement of intermediaries182. This finding can be explained by the fact that BCT enables disintermediation in healthcare transactions, improves efficiency, reduces costs, and enhances trust in the system101,102. Organizations and policymakers seeking to promote the adoption and use of blockchain in healthcare settings should focus on highlighting the potential benefits of the disintermediation enabled by BCT.

The result of H4 indicates that cost-effectiveness significantly impacts the fitness of blockchain to the HIS needs in Malaysian hospitals. This result supports previous findings on the impact of cost-effectiveness on the adoption of new technologies183. Many studies have shown that the cost-effectiveness of a technology is a critical factor influencing its adoption in healthcare systems worldwide184,185. BCT can help reduce costs by eliminating the need for intermediaries, improving efficiency by streamlining processes, improving accuracy by reducing errors, and improving security by making data more tamper-proof112,186.

The result of H5 indicates that the fitness of blockchain has a significant positive impact on the intention to adopt BCT-based HIS in hospitals. This suggests that hospitals are more likely to adopt BCT when it fits the needs and work of their existing systems. Many previous studies have shown that the perceived fitness of a technology, including its usability, functionality, and compatibility with existing systems, is a critical factor influencing its adoption65,187,188,189. Adopting a BCT-based HIS may require significant changes to existing systems and workflows, and healthcare providers are likely to consider the technology’s fitness before deciding to adopt it. Therefore, technology providers should focus on developing blockchain solutions specifically designed to meet the needs of healthcare organizations.

H6’s results demonstrate a noteworthy positive influence of top management support on the viability of adopting a BCT-based HIS. This aligns with previous research emphasizing the crucial role of top management support in the successful adoption of new technologies in healthcare settings such as blockchain24, RFID190, and Mobile health72. In addition, this finding supports previous studies60,73,78,80,81 that found TMS was a significant predictor of BCT adoption, and that the absence of top management support is a barrier to the adoption of BCT. Furthermore, this finding aligns with previous studies that have found that TMS positively impacts the viability of technology adoption65,66. Organizational management and investment decisions are frequently influenced by the support and understanding of top management27. When the top management possesses a higher level of knowledge about a particular technology, it increases the likelihood of developing a positive intention to adopt and support its implementation. Top management’s support plays a crucial role in the successful adoption of BCT131,191,192. The significance of top management support in adopting BCT can be attributed to their authority in approving strategic decisions, including adopting new technologies and allocating resources toward them73,193. Therefore, we suggest educating top management on BCT and its potential benefits. This will help in initiating the idea of BCT adoption and generating buy-in from top leadership, which can, in turn, foster a supportive environment for BCT adoption in hospitals194.

The results of H7 indicate that organizational readiness significantly impacts the viability of BCT-based HIS adoption in Malaysian hospitals. This finding is in line with those of previous studies that reported a positive and significant relationship between organizational readiness and blockchain adoption in healthcare112, elderly care60, SME27, and supply chain78. However, this finding contrasts with those of previous studies56,79 that reported a weak or non-significant relationship between organizational readiness and BCT adoption. The impact of organizational readiness on technology adoption can vary depending on the technical proficiency and resource sophistication within each organization and from one industry to another195. Healthcare providers in Malaysia should ensure that their organizations are ready to adopt blockchain-based HIS before deciding to adopt the technology, as this can significantly impact the success of the adoption and realization of the potential benefits of the technology. BCT adoption may require significant organizational structure and cultural changes, and organizational readiness is critical to ensure successful transition and adoption of the technology. They need to be ready to commit to and provide adequate funding for blockchain initiatives, and they also need to be able to adjust their spending to account for other expenditures such as start-up and ongoing expenses194,196,197. In addition, healthcare businesses need to have strong talent and knowledge acquisition skills because of the infancy and immaturity of BCT, and the constant changes and advances in the technological ecosystem. Therefore, healthcare organizations should develop readiness by ensuring adequate resources, training programs, and staff support to support the adoption of BCT-based HIS.

The result of H8 indicates that CSR does not significantly impact the viability of BCT-based HIS in Malaysian hospitals. This finding suggests that while CSR may be an essential consideration for healthcare providers in Malaysia, it may not significantly influence the adoption of blockchain-based HIS. This result could be explained by the fact that the adoption of BCT in healthcare is still in its early stages and organizations may prioritize other factors, such as cost-effectiveness and functionality, over CSR considerations. While this finding appears to contradict prior studies that have highlighted the importance of CSR in facilitating the adoption of BCT in elderly care60, it is essential to note that this study was conducted in a specific healthcare context that may have unique cultural, technological, and regulatory factors that could impact the relationship between CSR and blockchain adoption. The impact of CSR on technology adoption may vary depending on the specific context and culture of the healthcare system127.

The results of H9 indicate that mimetic pressure from competitors does not significantly impact the viability of BCT-based HIS adoption in Malaysian hospitals. This finding aligns with60, who reported that competitor pressure did not affect the adoption of BCT in elderly care. One possible explanation for this finding is the low-and early stage proportion of blockchain diffusion in healthcare organizations. Second, the healthcare system in Malaysia may not be highly competitive, with healthcare providers operating in a more collaborative environment. Third, healthcare providers in Malaysia may prioritize other factors, such as cost-effectiveness and organizational readiness, over competitors’ actions when making decisions about adopting new technologies. Conversely, several studies56,73,74 have highlighted that competitive pressure plays a pivotal role in driving an organization’s inclination toward adopt BCT. These studies emphasize the significance of BCT adoption for organizations to maintain their competitive edge. However, these studies utilized sectors other than the current study, such as construction56, SEMs73, and Supply chains74. This suggests that Malaysian hospitals are less susceptible to mimetic pressure from competitors than are firms in other contexts.

The results of H10 indicate that coercive pressure from the government has a significant negative impact on the viability of BCT-based HIS adoption in Malaysian hospitals. This result means that government support and regulations hinder the adoption of BCT-based HIS in Malaysian hospitals. This negative relationship implies that hospitals are unsatisfied with the government’s current initiatives for BCT. Hospital administrators may feel that the government does not provide them with sufficient support or resources to adopt BCT successfully. It may also be that the current regulations and policies formulated by the government are not enough to make hospital administrators feel that blockchain is viable for them. The lack of adequate government support, including the establishment of regulatory frameworks, hinders widespread adoption of blockchain among organizations56,60,74,78,81,198,199,200,201. This finding is consistent with previous studies24,34,40,41,133 that have identified government support and regulations as significant barriers to the adoption of BCT in healthcare settings. However, the results are contrary to studies of blockchain adoption in other sectors and domains, such as SEM73, Supply chain84,89,130, financial85, banking86, accounting87, and construction88, which found that government support and regulations positively impact BCT adoption. A possible explanation for this discrepancy is that the heavy regulations and complex policies of the healthcare industry make the adoption of BCT challenging. Government regulations are often inflexible, slow to adapt, and focused on data privacy and security, which may conflict with the transparency and data sharing enabled by the blockchain. The lack of collaboration between policymakers and health care providers has contributed to ineffective regulations. Therefore, clear and supportive government policies are necessary to foster BCT adoption in Malaysian hospitals. Additionally, collaboration between healthcare organizations, technology providers, and government agencies is crucial for aligning regulations with healthcare needs24.

The results of H11 indicate that partner readiness has a significant positive impact on the viability of BCT-based HIS adoption in Malaysian hospitals. This result is consistent with that of a previous study202 that highlighted the importance of considering partner readiness when making decisions about adopting new technologies in healthcare. Moreover, this finding aligns with the existing body of research and supports previous findings that partner readiness significantly determines BCT adoption in different sectors such as SEM73, supply chain54,89,99, and banking86. The significance of partner readiness in facilitating blockchain adoption can be attributed to the fact that it is a collaborative technology that requires multiple stakeholders to participate effectively in the network203. Thus, Hospital administrators should collaborate with their partners to assess their readiness to adopt BCT. Partners should be provided with support and resources to facilitate adoption. In addition, administrators should work with partners to develop a comprehensive adoption plan for BCT.

The results of H12 indicate that technology vendor support has a significant positive impact on the viability of BCT-based HIS adoption in Malaysian hospitals. These results are consistent with previous findings that technology vendor support is a significant determinant of technology adoption in Malaysian hospitals43,106. In addition, this finding aligns with a study78 that found that the level of support provided by technology vendors, including training, technical assistance, and customization, strongly influences the adoption of BCT. This finding can be explained by several factors: First, the level of support provided by technology vendors can impact the level of expertise and knowledge available to healthcare providers, which can be critical for the successful adoption of technology. Second, technology vendor support can impact the level of customization and integration of the technology with existing systems, which can influence the overall success of adoption. Thus, healthcare providers in Malaysia should carefully evaluate the level of support provided by technology vendors when considering the adoption of BCT-based HIS and should prioritize partnerships with vendors that offer high levels of support and customization to ensure the successful adoption of the technology.

The result of H13 indicates that viability has a significant positive impact on the intention to adopt a BCT-based HIS in Malaysian hospitals. This finding is in line with those of previous studies, which stated that viability is a significant predictor of technology adoption31,65,187. Several factors explain this finding. First, the perceived viability of the technology can influence the level of support and resources provided for its implementation. Second, the perceived viability of the technology can affect the level of expertise and knowledge available to healthcare providers, which can be critical for the successful adoption of the technology. This finding underscores the need for healthcare organizations to carefully evaluate the feasibility and usefulness of BCT before deciding to adopt it, and to invest in education and awareness-raising efforts to promote a better understanding of the potential benefits and limitations of BCT in healthcare information systems.

The results of the multi-group analysis for the moderating variable of the type of hospital indicate no significant differences in the relationship between the factors and BCT-based HIS adoption in Malaysian hospitals, based on whether the hospital is public or private. None of the path coefficients showed a significant difference according to the type of hospital, as all p-values were greater than 0.05. Thus, H14 was not supported. There are several potential reasons for the lack of statistically significant differences between public and private hospitals in this analysis. First, the health care system in Malaysia may be relatively homogenous, with both public and private hospitals facing similar challenges and opportunities when adopting new technologies. In addition, public and private hospitals may operate in similar healthcare environments, resulting in similar effects of constructs on adoption outcomes. For example, both types of hospitals may face similar regulatory pressures, patient populations, and resource constraints, which may have a similar impact on adopting a BCT-based HIS. Second, the factors influencing blockchain-based HIS adoption may be consistent across both public and private hospitals, with both types of hospitals prioritizing similar factors such as cost-effectiveness, organizational readiness, and partner support.

Moreover, the lack of statistically significant differences between public and private hospitals may be due to limitations in the sample size. A larger sample size may be required to detect significant differences in the impact of constructs on adoption outcomes between public and private hospitals.

Overall, the study’s findings validated an integrative model that combined the aspects of three well-established theories: TOE, INS, and FVM. The technological, organizational, and environmental dimensions of the TOE framework explain the variance in both technology fit and viability. This supports the consideration of factors from all three contexts, as specified by TOE. Within the environmental dimension, this study validated the inclusion of mimetic and coercive pressures from institutional theory. Although mimetic pressure was not significant, coercive pressure negatively affected viability. This result validates drawing on the INS to identify relevant pressure factors. The identification of technology fit and viability as constructs between contextual factors and intention to adopt was validated by the FVM component of the model. Both fit and viability were significantly influenced by TOE factors and significantly influenced intention, in line with FVM. Thus, the results indicate that the integrated model provides a comprehensive theoretical basis encompassing technological, organizational, institutional, and fit/viability perspectives to understand blockchain adoption in healthcare. Each theory contributes meaningfully, enabling a more holistic understanding that cannot be attained through a single framework. The integrated model was empirically well supported, with high explanatory power. It validates the value of synthesizing multiple established adoption theories to develop a robust theoretical lens for studying new technologies, such as blockchain.

Theoretical implications

This study enriches the body of research on new technology adoption by integrating the TOE framework, the FVM model, and institutional theory to develop a comprehensive model for BCT adoption in healthcare. This study goes beyond the limitations of previous research that failed to evaluate the factors influencing BCT adoption in healthcare settings. This study provides empirical evidence on how external institutional pressures such as government coercion impact BCT adoption in hospitals, thereby validating the applicability of institutional theory in this context. Furthermore, the study extends the TOE framework by incorporating the FVM model to assess the fitness and viability of BCT-based HIS in hospitals, considering unique technology attributes and organizational and environmental factors. The inclusion of fit and viability in the present study’s model emphasizes their crucial role in BCT-based HIS adoption, and points to the need for further research considering these factors. The findings underline the consistent drivers of BCT adoption across both public and private hospitals, suggesting that hospital type should be considered a control variable in future research on BCT adoption in healthcare.

By merging TOE, institutional theory, and FVM, this study presents a novel integrated model that offers valuable insights into the adoption of healthcare technologies. The developed conceptual model can also be applied to other sectors, thus providing a foundation for future research on technology adoption. The outcomes of this study are beneficial for both researchers and businesses interested in advancing BCT-based healthcare solutions.

Practical implications

The findings of this study have practical implications for Malaysian hospitals and other healthcare organizations that consider adopting BCT. By identifying the factors influencing adoption intentions, these organizations can make well-informed decisions and develop effective strategies to overcome potential barriers and challenges. The model developed in this study can serve as a valuable guideline for assessing and evaluating these factors, aiding decision-making, and anticipating influences that lead to improved system implementation processes. Furthermore, policymakers and regulators interested in promoting the adoption of BCT in the healthcare sector can benefit from this study’s identification of the potential benefits and challenges.

The significance of the relationships between technology trust, information transparency, perceived intermediation, and cost-effectiveness with the suitability of BCT-based HIS can be attributed to their vital role in addressing challenges faced by healthcare systems, such as data privacy and security, interoperability, and inefficiencies. These characteristics of BCT are influential factors that drive the adoption of BCT-based HIS, as hospitals recognize their benefits. Consequently, this highlights the importance of raising awareness regarding the advantages of BCT-based HIS adoption. Collaboration among government organizations, service providers, and technology vendors is crucial for promoting the understanding and awareness of BCT in healthcare. The government should implement intervention plans to educate and train senior hospital management and healthcare staff in order to improve awareness. In addition, blockchain service providers should share the success stories of blockchain implementation in healthcare organizations. These actions aim to inspire healthcare organizations, mitigate doubts, and demonstrate practical applications of BCT. Recognizing the potential of BCT-based HIS can significantly enhance the work practices of clinical and non-clinical staff, serving as a significant advancement in resolving critical issues within Malaysian hospitals.