Abstract

Stroke is a sudden neurological decline caused by cerebrovascular diseases or impaired blood circulation. Research investigating the connection between glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels and stroke severity is limited. This study examined the connection between HbA1c levels and stroke severity in patients with acute ischemic stroke. A retrospective cross-sectional analysis of the medical records of 1103 patients with acute ischemic stroke from January 2020 to January 2024 was conducted. Patients were divided into seven groups on the basis of their HbA1c levels. Stroke severity within these groups was assessed via the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), with the aim of identifying correlations between stroke severity and glycemic status. This study examined the impact of various HbA1c levels on a range of demographic and clinical characteristics in stroke patients. The patients were grouped into seven categories on the basis of their HbA1c levels, and characteristics such as age; body mass index (BMI); LDL, HDL, and creatinine levels; and NIHSS scores at hospital admission were compared across these groups. Significant differences were observed in age, LDL levels (F = 3.999, P < 0.001), and creatinine levels (F = 1.303, P = 0.253) among the HbA1c categories. However, there were no significant differences in BMI, HDL levels, or length of hospital stay. A positive correlation was found between HbA1c levels and NIHSS scores, indicating that higher HbA1c levels are associated with greater stroke severity. This study revealed that the risk of severe stroke increases significantly when HbA1c levels exceed 6.5%. In contrast, maintaining HbA1c levels below 6.5% is linked to a reduced risk of severe stroke and lower mortality. Additionally, older adults are at greater risk and tend to experience more severe strokes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stroke is a sudden neurological dysfunction caused by cerebrovascular disease of two main types: ischemic and hemorrhagic. Ischemic strokes, which constitute approximately 71% of all cases, occur due to blockage of an artery in the brain, spinal cord, or retina1,2. It is the second leading cause of death globally and is responsible for approximately 10% of annual fatalities. In 2019, more than 7 million people died from strokes worldwide, an increase of approximately 5.4 million deaths in 20003. Furthermore, stroke is a significant contributor to long-term disability, with approximately 44.5% of stroke survivors experiencing some level of impairment4. According to a 2022 report from the American Heart Association, the United States experienced approximately 765,000 stroke cases5. A clinical study conducted in Saudi Arabia revealed that stroke is the second leading cause of death in the country. While comprehensive statistics on stroke in Saudi Arabia are lacking, in 2020, a study was published that estimated an annual incidence of 29 stroke cases per 100,000 people6.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) plays a critical role in causing various complications that impact both small and large blood vessels, potentially leading to serious conditions such as vision loss, kidney failure, heart attack, and thrombosis7,8. DM is characterized by consistently high blood sugar levels and disruptions in the body’s processing of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. These metabolic problems result from either a complete or partial deficiency in insulin secretion and/or impaired insulin function. Recent research conducted in the United States aimed at assessing stroke risk in individuals with type 2 diabetes revealed a two-peak pattern in the relationship between stroke incidence and HbA1c levels9,10. Moreover, patients with either poor or overly strict glycemic control (HbA1c levels above 6%) are more likely to experience ischemic stroke than hemorrhagic stroke11,12. Furthermore, other health conditions, such as coronary heart disease (CHD), hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, renal disease, and cancer, can increase the likelihood of experiencing a more severe stroke13,14. Certain mental health conditions are associated with a greater risk of severe stroke. However, most research on the link between HbA1c levels and the severity of acute ischemic stroke has concentrated on individual factors and their effects on outcomes such as survival rates, quality of life, and healthcare use. The impact of different HbA1c levels on stroke severity in the general population remains uncertain. A clearer understanding of how varying HbA1c levels influence stroke severity could enhance the development of stroke prevention strategies15,16. As a result, this study conducted a prospective analysis to explore the relationship between different HbA1c levels and stroke severity, using data from a retrospective cross-sectional study involving patients with acute ischemic stroke.

Methods

Study design and data collection

The institutional review board at King Abdullah International Medical Research Centre (KAIMRC) provided ethical approval for this study. Upon receiving ethical approval, the research team contacted the medical records unit, research department, and data management section at KAIMRC, which is part of the Ministry of National Guard-Health Affairs in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, to collect data. We obtained informed consent from the patients to use their medical information. The methods were conducted in compliance with the applicable guidelines and regulations.

The diagnostic criteria for ischemic stroke in enrolled patients generally follow guidelines from established medical organizations, like the American Stroke Association (ASA). “The diagnostic criteria include clinical symptoms such as unilateral weakness, headaches, speech difficulties, vision problems, trouble swallowing, and loss of communication, all of which should emerge suddenly and not be linked to other conditions. Additionally, a neurological exam is essential, focusing on assessing focal neurological deficits such as motor issues, numbness, sensory disturbances, or speech problems, as well as looking for asymmetry in reflexes, muscle strength, and sensation. Diagnostic tests, including blood tests (e.g., complete blood count, coagulation tests, metabolic disturbances), CT scans, MRIs, echocardiograms, and carotid ultrasounds, are also part of the diagnostic criteria. Moreover, identifying risk factors for stroke and thrombosis, such as hypertension, diabetes, smoking, hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation, and a history of transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) or strokes, is fundamental in the diagnostic process. Patient information was extracted from electronic health records via the hospital’s data management systems. To maintain patient confidentiality, codes were assigned instead of patients’ names or medical record numbers. The study examined the records of 1103 patients (398 males and 705 females) who had experienced a stroke. Patients aged 18 to 100 years with stroke lesions were included, whereas individuals aged 18 or over 100 years were excluded. HbA1c levels were measured and analyzed for all patients. As this was a retrospective study, the KAIMRC ethics committee waived the need for informed consent, and all identifying information was removed to ensure confidentiality. The study adhered to the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and local institutional standards. The objective of this study was to assess how different HbA1c levels and other health conditions impact stroke severity among patients at King Abdulaziz Medical City.

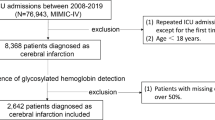

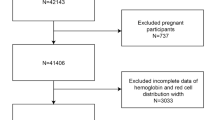

A retrospective cross-sectional analysis was performed on the medical records of 1103 stroke patients admitted between January 2020 and January 2024. The inclusion criteria consisted of patients who had a confirmed diagnosis of ischemic stroke between January 1, 2020, and January 1, 2024, and were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). Patients with incomplete data or those under 18 years old were excluded from the study. The sentence in the revised manuscript has been updated to: Patients were classified into seven groups based on their HbA1c levels, following the American Diabetes Association (ADA) guidelines17. Group 1 (HbA1c < 5.4), Group 2 (HbA1c 5.4–5.6), Group 3 (HbA1c 5.7–5.9), Group 4 (HbA1c 6.0–6.4), Group 5 (HbA1c 6.5–6.9), Group 6 (HbA1c 7.0–7.9), and Group 7 (HbA1c ≥ 8.0. Stroke severity was assessed across these HbA1c groups via the NIHSS to explore correlations between stroke severity and glycemic status. One-way ANOVA was used to compare baseline patient characteristics across the HbA1c categories, and mortality rates were analyzed via one-way ANOVA across HbA1c quartiles. The chi-square test was employed to examine differences in nominal variables, such as sex, and to compare stroke severity between male and female patients. The study outcomes included stroke severity and mortality rates, with statistical significance set at a P value of < 0.05.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed via SPSS® software version 25.00 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and graphical representation was performed via GraphPad Prism version 9.4.1 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Descriptive data are presented mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables, while percentages and frequencies are presented for categorical variables. One-way ANOVA was conducted to compare baseline patient characteristics across the HbA1c categories. Multiple linear regression analysis was performed to examine the association between HbA1c levels and potential predictors, adjusting for age, gender, smoking status, and NIHSS admission score.

Results

Table 1 displays the results of a one-way ANOVA that assesses the impact of varying HbA1c levels on a range of demographic and clinical characteristics in stroke patients. The patients were divided into seven groups on the basis of their HbA1c levels, and the following characteristics were compared across these groups: age; body mass index (BMI); LDL, HDL, and creatinine levels; NIHSS scores at hospital admission; and length of hospital stay. The analysis revealed significant differences in age (F = 5.611, P < 0.001), indicating that age varies significantly across the different HbA1c categories. However, no significant difference in BMI was observed (F = 1.215, P = 0.296) across the HbA1c groups. Significant differences were found in LDL levels (F = 3.999, P < 0.001) and creatinine levels (F = 2.523, P = 0.020) across the HbA1c categories. Conversely, there was no significant difference in HDL levels (F = 1.303, P = 0.253) or length of hospital stay (F = 1.896, P = 0.078) between the HbA1c groups. Additionally, the NIHSS score at hospital admission was significantly different (F = 17.154, P < 0.001) across the HbA1c categories. Furthermore, as indicated in Table 2, the gender distribution revealed that 398 (36.1%) patients were female and 705 (63.9%) were male. The findings showed a higher prevalence of ischemic stroke among males compared to females. Additionally, in our study, 161 (14.6%) patients with ischemic stroke were smokers, while 942 (85.4%) were nonsmokers. The present study found no significant difference in stroke severity at admission between smokers and non-smokers. Additionally, no statistically significant difference was observed in the NIHSS score at admission between the two groups. Overall, the analysis does not demonstrate a clear relationship between smoking and either HbA1c levels or NIHSS scores at admission with respect to stroke severity (as shown in Table 2).

Table 3 presents the results of an independent samples t test, which was conducted to compare the HbA1c levels and NIHSS scores upon hospital admission between males and females. For HbA1c, there was no significant difference between males and females (mean ± standard deviation: females: 7.95 ± 2.3, males: 8.03 ± 2.3). The t test results were t = − 0.495, P = 0.621. Similarly, no significant difference was found in the NIHSS score at admission between males and females (mean ± standard deviation: females: 10.1 ± 8.9, males: 10.9 ± 8.5). The t test results were t = − 1.343, P = 0.180. Since the P values are greater than 0.05, these results suggest that there was no significant difference.

The results showed variation in stroke severity across different HbA1c levels upon admission, with varying proportions of mild, moderate, and severe stroke cases in each group. A P value of 0.332 indicates that there is no statistically significant correlation between HbA1c levels, and the severity of ischemic stroke based on the NIHSS scale (Table 4).

As shown in Table 5, a multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between HbA1c levels and the predictor variables, including NIHSS admission, age, gender, smoking status, LDL, HDL, and BMI. The overall regression model was statistically significant, F (7, 1095) = 20.055, p < 0.001, explaining 11.4% of the variance in HbA1c levels (R2 = 0.114, Adjusted R2 = 0.108).

Among the predictors, NIHSS admission remained a significant positive predictor of HbA1c levels (B = 0.084, SE = 0.008, β = 0.317, t = 11.112, p < 0.001), indicating that higher NIHSS scores are associated with increased HbA1c levels. Additionally, smoking status (B = 0.449, SE = 0.196, β = 0.069, t = 2.285, p = 0.023) and BMI (B = 0.203, SE = 0.079, β = 0.074, t = 2.567, p = 0.010) were also significant predictors, suggesting that smokers and individuals with higher BMI tend to have higher HbA1c levels.

However, age (p = 0.454), gender (p = 0.314), LDL (p = 0.341), and HDL (p = 0.153) did not significantly predict HbA1c levels, indicating that these variables did not contribute meaningfully to the variation in glycemic control in this model.

Table 6 presents the results of the chi-square test, which revealed significant differences in mortality rates based on baseline HbA1c levels in stroke patients. The mortality rate increases as HbA1c levels rise, a trend observed in both males and females, as well as in the overall sample. Significant differences in mortality rates according to HbA1c levels were found across all groups (Fig. 1).

Discussion

This study carried out a prospective analysis to investigate the relationship between various HbA1c levels and stroke severity, utilizing data from a cross-sectional study of patients with acute ischemic stroke. Our study included patients diagnosed with ischemic stroke who were admitted to the hospital between January 2020 and January 2024, regardless of whether they were admitted to general wards or the intensive care unit (ICU). The study focused on patients with a confirmed ischemic stroke diagnosis within this time frame, and those admitted to the ICU were included. These factors include age, BMI, LDL, HDL, and creatinine levels; NIHSS scores at hospital admission; and the length of hospital stay. Patients are categorized into seven groups on the basis of their HbA1c levels, with the study showing significant differences in age among these groups. Advancing age is recognized as a factor that increases the risk of stroke. A previous study revealed that in Saudi Arabia, both the incidence and severity of stroke increase with age and continue to increase through the seventh decade of life18. In the present study, as shown in Table 1, higher HbA1c levels were associated with older age, demonstrating a noticeable difference in age across the HbA1c categories. Patients aged 60 and above had higher HbA1c levels, while those with a median age under 60 exhibited lower levels of HbA1c. Furthermore, the present study suggested that although HbA1c levels impact certain health parameters, they have minimal effects on BMI in stroke patients. Another characteristic that exhibits substantial variation across the HbA1c categories, LDL levels, also showed considerable variation among the different HbA1c categories, indicating a potential link between HbA1c levels and increased LDL concentrations. Elevated LDL levels were found to be positively correlated with the severity of stroke risk and to affect the severity of ischemic stroke through an interactive mechanism. This relationship could affect how cardiovascular health is managed in stroke patients. In contrast, HDL levels did not significantly vary across different HbA1c categories, indicating that HbA1c levels do not have a major effect on HDL levels19,20.

The creatinine levels of stroke patients vary significantly across HbA1c categories, which may indicate a connection between glycemic control and kidney function. Elevated serum creatinine levels serve as a marker for a greater risk of cerebrovascular damage. These findings reinforce the evidence that even minor kidney dysfunction contributes to increased stroke risk and suggest potential mechanisms involved in stroke development21,22. Higher HbA1c levels may be associated with more severe strokes at the time of hospital admission, as NIHSS scores at admission show a significant variation with HbA1c levels23. However, according to Wu et al., no significant difference in hospital stay duration was observed across the various HbA1c categories. However, a separate study found that higher HbA1c levels in stroke patients were an independent predictor of poor functional outcomes in individuals with ischemic stroke, and this association persisted even after controlling for initial blood glucose levels24. Another study also revealed that high pre-stroke HbA1c levels are strongly associated with increased stroke severity and a greater risk of one-year all-cause mortality. An HbA1c level of ≥ 7.2% independently predicts one-year all-cause mortality following initial ischemic stroke25. They suggested that stringent glycemic control is essential for diabetic patients at high risk. This suggests that while higher HbA1c levels impact stroke severity at admission, they do not influence the length of hospital stay after a stroke. There was also an investigation into sex differences in HbA1c levels and NIHSS scores at the time of hospital admission. There was no statistically significant difference in the levels of HbA1c between males and females, nor was there a statistically significant difference in the values of the NIHSS score at the time of admission between males and females. In 2009, research indicated that the incidence of stroke in men was approximately 30% higher than that in women26,27. Additionally, another study revealed that the prevalence of stroke was significantly greater in men aged 40 and older than in women of the same age group28. While previous studies have indicated that smokers generally have higher HbA1c levels than non-smokers, suggesting that smoking may increase insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and inflammation—factors that can disrupt glucose metabolism and raise HbA1c levels29,30—the current study found the opposite. It showed that smokers had lower HbA1c levels compared to non-smokers, as shown in Table 2. To our knowledge these findings have not been previously reported and may offer new insights into the varying stroke prognoses observed in smokers, as reported in previous studies. In the existing literature, Weng, Wei-Chieh et al. found no significant difference in the changes in NIHSS scores from hospital admission to discharge between smokers and non-smokers31. Nonetheless, the prognostic impact of smoking remains a subject of ongoing debate. Previous research has indicated that smoking, along with other risk factors, may contribute to increased mortality rates and enhanced stroke severity over the long term32. As discussed in the literature, multiple factors underlie the contradictory effects of smoking on stroke severity. Additionally, smoking may reduce the initial severity of strokes, further complicating predictions regarding outcomes in smokers with stroke31,33.

This study delves further into the correlation between hemoglobin A1c levels, and the severity of stroke as measured by the NIHSS. There was no statistically significant correlation between hemoglobin A1c levels, and the severity of stroke as measured by the NIHSS, even though there were different proportions of mild, moderate, and severe strokes in each HbA1c category. However, the HbA1c value and the NIHSS score at admission to the hospital were positively correlated and to a moderate degree. These findings indicate that the severity of a stroke at admission is greater in patients with higher HbA1c levels.

Finally, the study identified substantial disparities in mortality rates among stroke patients according to their baseline HbA1c levels. There was a trend in the overall sample and among males and females that higher HbA1c levels were associated with increased mortality rates26,27. These findings emphasize the importance of glycemic control in reducing mortality risk in stroke patients.

Conclusions

The present study indicates that higher HbA1c levels were linked to older age, with a notable difference in age across the HbA1c categories. As shown in Table 1, patients over 60 years of age had higher HbA1c levels, while those with a median age under 60 had lower levels of HbA1c. A previous study has highlighted a significant association between stroke severity and advanced age. However, no significant differences in BMI were observed. The risk and severity of stroke are markedly elevated in older individuals15. whereas sex does not significantly affect these measures. Notable differences in hemoglobin A1c levels are observed between smokers and nonsmokers, with smokers having lower levels. However, there was no significant difference in the NIHSS score at admission between the two groups. These findings indicate that while smoking status influences HbA1c levels, it does not affect the severity of stroke at the time of admission. Efforts to promote public awareness campaigns targeting the population, as well as initiatives for the early detection of chronic diseases and diabetes, should be encouraged. Such measures are essential for increasing awareness and lowering stroke rates as well as the severity of stroke in the community.

Data availability

Data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author, Dr. Naif M. Alhawiti, upon request.

References

Kanter, J. E. & Bornfeldt, K. E. Impact of diabetes mellitus. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc Biol. 36 (6), 1049–1053 (2016).

Wu, Y., Ding, Y., Tanaka, Y. & Zhang, W. Risk factors contributing to type 2 diabetes and recent advances in the treatment and prevention. Int. J. Med. Sci. 11 (11), 1185 (2014).

Feigin, V. L. et al. Global, regional, and National burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 20 (10), 795–820 (2021).

Chen, L., Magliano, D. J. & Zimmet, P. Z. The worldwide epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus—present and future perspectives. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 8 (4), 228–236 (2012).

lqahtani, B. A. et al. Incidence of stroke among Saudi population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol. Sci. 41, 3099–3104 (2020).

Tsao, C. W. et al. Heart disease and stroke Statistics—2022 update: A report from the American heart association. Circulation 145, e153–e639 (2022).

Chen, R., Ovbiagele, B. & Feng, W. Diabetes and stroke: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, pharmaceuticals and outcomes. Am. J. Med. Sci. 351 (4), 380–386 (2016).

Kuriakose, D. & Xiao, Z. Pathophysiology and treatment of stroke: Present status and future perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 (20), 7609 (2020).

Ramos-Lima, M. J., Brasileiro, I. D., Lima, T. L. & Braga-Neto, P. Quality of life after stroke: Impact of clinical and sociodemographic factors. Clinics 73 (2), 245–255 (2018).

Coupland, A. P., Thapar, A., Qureshi, M. I., Jenkins, H. & Davies, A. H. The definition of stroke. J. R Soc. Med. 110 (1), 9–12 (2017).

Saini, V., Guada, L. & Yavagal, D. R. Global epidemiology of stroke and access to acute ischemic stroke interventions. Neurology 97 (2), S6–16 (2021).

Alqahtani, B. A. et al. Incidence of stroke among Saudi population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol. Sci. 41, 3099–3104 (2020).

Mitsios, J. P., Ekinci, E. I., Mitsios, G. P., Churilov, L. & Thijs, V. Relationship between glycated hemoglobin and stroke risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 7 (11), e007858 (2018).

Bao, Y. & Gu, D. Glycated hemoglobin as a marker for predicting outcomes of patients with stroke (ischemic and hemorrhagic): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 12, 642899 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Association of total preexisting comorbidities with stroke risk: A large-scale community-based cohort study from China. BMC Public Health 21, 1–9 (2021).

Cipolla, M. J., Liebeskind, D. S. & Chan, S. L. The importance of comorbidities in ischemic stroke: Impact of hypertension on the cerebral circulation. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 38 (12), 2129–2149 (2018).

American diabetes A. Standards of medical care in diabetes-2010. Diabetes Care 33 (1), S11–61 (2010).

Alfakeeh, F. K. et al. HbA1c and risk factors’ prevalence in patients with stroke: A retrospective study in a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. Neurosci. J. 29 (1), 18–24 (2024).

Chan, Y. H. et al. Glycemic status and risks of thromboembolism and major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 19, 1–4 (2020).

Nomani, A. Z. et al. High HbA1c is associated with higher risk of ischaemic stroke in Pakistani population without diabetes. Stroke Vasc. Neurol. 1 (3) (2016).

Zhang, A. et al. Association of lipid profiles with severity and outcome of acute ischemic stroke in patients with and without chronic kidney disease. Neurol. Sci. 42, 2371–2378 (2021).

Wannamethee, S. G., Shaper, A. G. & Perry, I. J. Serum creatinine concentration and risk of cardiovascular disease: A possible marker for increased risk of stroke. Stroke 28 (3), 557–563 (1997).

Tsagalis, G. et al. Renal dysfunction in acute stroke: An independent predictor of long-term all combined vascular events and overall mortality. Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 24 (1), 194–200 (2009).

Wang, H., Chen, S., Li, X., Zhu, Z. & Zhang, W. Impact of elevated hemoglobin A1c levels on functional outcome in patients with acute ischemic stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 28 (2), 470–476 (2019).

Wu, S. et al. HbA1c is associated with increased all-cause mortality in the first year after acute ischemic stroke. Neurol. Res. 36 (5), 444–452 (2014).

Hjalmarsson, C., Manhem, K., Bokemark, L. & Andersson, B. The role of prestroke glycemic control on severity and outcome of acute ischemic stroke. Stroke Res. Treat. 2014 (1), 694569 (2014).

Appelros, P., Stegmayr, B. & Terént, A. Sex differences in stroke epidemiology. Stroke 40, 1082–1090 (2009).

Wang, W. et al. Prevalence, incidence, and mortality of stroke in China: Results from a nationwide population-based survey of 480 687 adults. Circulation 135, 759–771 (2017).

Gaind, S., Suresh, D. K. & Tuli, A. Evaluation of glycosylated hemoglobin levels and effect of tobacco smoking in periodontally diseased non-diabetic patients. Int. J. Maternal Child Health AIDS 13 (e007), 1–7 (2024).

Gupta, S. et al. Status of tobacco smoking and diabetes with periodontal disease. JNMA J. Nepal Med. Assoc. 56 (213), 818–824 (2018).

Weng, W. C. et al. The impact of smoking on the severity of acute ischemic stroke. J. Neurol. Sci. 308 (1–2), 94–97 (2011).

Ovbiagele, B. & Saver, J. L. The smoking–thrombolysis paradox and acute ischemic stroke. Neurology 65 (2), 293–295 (2005).

Bang, O. Y. et al. Improved outcome after atherosclerotic stroke in male smoker. J. Neurol. Sci. 260 (1–2), 43–48 (2007).

Acknowledgements

NA.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NMA was responsible for the study conception, design, data acquisition, and manuscript writing. EME, JAA, and BAA contributed to the statistical analysis, data collection, literature review, and co-wrote the results section. All authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final manuscript. Each author made significant contributions to the article and approved the version submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the institutional review board at King Abdullah International Medical Research Centre (KAIMRC) provided ethical approval for this study under number # NRR24/028/8) waived the need of obtaining informed consent in the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alhawiti, N.M., Elsokkary, E.M., Aldali, J.A. et al. Investigating the impact of glycated hemoglobin levels on stroke severity in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Sci Rep 15, 12114 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95305-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95305-2