Abstract

Gastric parietal cells (gastric acid-secreting cells) secrete estrogen in response to blood lipid (triglycerides [TG] and fatty acids [FFA]) levels. Since estrogen helps reduce blood lipid levels, gastric estrogen would be important in lowering elevated blood lipid levels. However, gastric parietal cells use lipid-derived energy for estrogen production and acid secretion. Thus, postprandial changes in blood lipid levels and acid secretion could affect gastric estrogen production. Here, we show that blood estrogen and FFA decrease after meals, especially after carbohydrate intake. Postprandially decreased blood estrogen levels are partially restored by intravenous lipid injections. Hormones that activate and suppress gastric acid secretion decrease and increase estrogen production in isolated gastric gland epithelia, respectively. Suppression of gastric acid secretion increases blood estrogen levels in postprandial, but not in fasted, rats. Carbohydrate ingestion releases insulin, which lowers blood FFA levels, while lipid intake releases hormones that suppress gastric acid secretion, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). Insulin and gastric estrogen directly enter the liver in high concentrations, enhancing and suppressing hepatic de novo lipogenesis, respectively. The more lipids ingested, the less lipogenesis is required. Therefore, we propose that ingested carbohydrates and lipids negatively and positively control gastric estrogen production, respectively, for proper hepatic lipogenesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Maintaining energy homeostasis, especially keeping blood glucose and lipid (triglycerides [TG] and fatty acids [FFA]) levels within appropriate ranges, is critical for life. Since the discovery of insulin in 1921, the regulation of blood glucose levels has been studied in detail1. However, until recently, it was unclear which organs monitor blood lipid levels or which hormones lower elevated blood lipid levels.

In 2021, we reported that gastric parietal cells (the cells that secrete gastric acid) secrete estrogen in response to blood lipid levels, using male and ovariectomized female rats2. Estrogen, synthesized from testosterone by aromatase, is secreted from adipocytes and gastric parietal cells, besides from the ovaries3,4,5,6. Whole-body aromatase PET and immunostaining revealed that the stomach—particularly gastric parietal cells—represents a significant tissue expressing this enzyme7. Aromatase requires energy to produce estrogen (3x NADPH / estrogen),3 and gastric parietal cells generate energy using FFA, not glucose2. When TG is administered orally, blood estrogen levels increase in response to the increase in blood TG levels but remain unchanged in gastrectomized rats2. Estrogen levels in stomach tissues correlate with blood TG levels, and isolated gastric gland epithelia produce estrogen in a FFA-dependent manner2. Estrogen is not just a sex hormone— it is a multi-target and multi-functional hormone. In addition to follicular growth and ovulation, estrogen regulates energy homeostasis, bone metabolism, brain function, and skeletal growth8. Above all, estrogen suppresses feeding behavior, lipogenesis, and lipolysis while enhancing lipid storage and consumption9,10,11,12,13, all contribute to lower blood lipid levels. Women’s blood triglyceride levels are lower than men’s but increase after menopause9. We therefore previously proposed a model in which gastric parietal cells secrete estrogen in response to blood lipid levels to lower elevated blood lipid levels2.

Unlike estrogen from other organs, such as the ovaries, gastric estrogen enters the liver directly in high concentrations, similar to insulin from the pancreas, regardless of gender6,14,15. Insulin enhances the liver’s uptake of blood glucose, storing it as glycogen and lipids converted through de novo lipogenesis, while estrogen suppresses the latter lipogenesis11,16. Just as insulin dysfunction can cause hyperglycemia, gastric estrogen dysfunction could cause hyperlipidemia and fatty liver. Since the number of gastric parietal cells and blood testosterone levels decrease with age17,18, gastric estrogen production is likely to decrease as well. Indeed, hyperlipidemia and fatty liver are common among the elderly19. Thus, a new subcategory of “gastric estrogen dysfunction” may be added to hyperlipidemia and fatty liver diseases. However, because gastric parietal cells use energy derived from lipids for acid secretion and estrogen production, it is important to clarify how postprandial changes in blood lipid levels and gastric acid secretion affect gastric estrogen to understand its dynamics and role in daily life.

Here, we show that carbohydrate intake and the activation of gastric acid secretion decrease gastric estrogen production and the subsequent blood estrogen levels. We first used male rats to investigate the effects of diet and gastric acid secretion on gastric estrogen production and blood estrogen levels. Blood estrogen levels decrease after meals, especially after carbohydrate intake. Blood FFA levels also decrease, and direct elevation of blood FFA levels by intravenous lipid injection partially restores the postprandially decreased blood estrogen levels. Estrogen levels in the portal vein, about 3.8 times those in the systemic vein, also decrease after meals. Hormones that enhance and suppress gastric acid secretion lead to decreased and increased estrogen production in isolated gastric gland epithelia, respectively. Suppression of gastric acid secretion restores the decreased estrogen production caused by hormones that enhance gastric acid secretion in vitro and the postprandially decreased blood estrogen levels in vivo. Finally, we conducted key experiments using female rats in the metestrous phase and confirmed results similar to those observed in male rats.

Diet activates gastric acid secretion, and carbohydrate intake reduces blood FFA levels via insulin20. Both processes decrease gastric estrogen production, leading to an increase in hepatic lipogenesis. Conversely, lipid intake not only increases blood TG levels but also promotes the release of hormones that suppress gastric acid secretion, such as glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), and cholecystokinin (CCK)21. Both processes increase gastric estrogen production, resulting in a decrease in hepatic lipogenesis. The more lipids ingested, the less lipogenesis is required. Therefore, gastric estrogen, along with insulin, would play an important role in proper hepatic lipogenesis based on the ingested carbohydrates and lipids.

Results

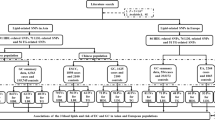

Blood Estrogen decreases after meals, especially after carbohydrate intake in males

First, we examined the changes in blood estrogen levels after feeding a high-fat diet (HFD) and a normal diet (ND). Rats fed HFD were given a week to adapt to the diet before the experiment. Eight-week-old male rats fasted for 12 h were fed either HFD or ND ad libitum for 30 min. We monitored the levels of blood TG, FFA, glucose, and estradiol (E2), the most potent estrogen (Fig. 1a). Blood TG levels increased and peaked 2 h after feeding in HFD-fed rats, but exhibited a decreasing trend—though not significantly—in ND-fed rats. Because blood E2 levels increase in response to the increase in blood TG levels elevated by oral or intravenous TG administration2, we expected that blood E2 levels would increase in HFD-fed rats but not in ND-fed rats. However, in both rats, blood E2 levels decreased immediately after feeding, with increased blood glucose and decreased blood FFA levels.

Blood estrogen decreases after meals, especially after carbohydrate intake in males. Eight-week-old male rats were deprived of food for 12 h. a Rats were fed either a high-fat diet (HFD, red) or a normal diet (ND, blue) ad libitum for 30 min (from −0.5 to 0 h, bars). Blood triglyceride (TG), fatty acids (FFA), glucose, and estrogen (E2) levels in the tail vein were measured before (−0.5) and at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 h after feeding. Rats fed HFD were allowed a week to adapt to the diet before the experiment. b and c Rats were orally administrated either carbohydrate (4 g starch per kg of body weight, blue), TG (2.5 mL olive oil per kg of body weight, red), or protein (2 g casein per kg of body weight, green) using intragastric gavage technique. Blood TG, FFA, glucose, and E2 levels in the tail vein were measured before (0) and at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 h after administration (b). Correlation diagram between blood FFA and E2 levels of carbohydrate-administered rats at 1 h after administration (c). d Rats were fed ND ad libitum for 30 min. Blood TG, FFA, glucose, and E2 levels in the tail vein and blood E2 levels in the portal vein were measured 2 h after feeding (blue). Fasted rats were used as control “pre-fed” rats (brown). Data are represented as mean ± s.d. n = 8. a, b, d P values were determined by a two-sided Student’s t-test between the indicated data sets. c, R and P values determined by Pearson’s product-moment correlation with a 95% density ellipse. Raw data are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, HFD and ND are mainly composed of carbohydrates, TG, and proteins, and their content ratios were 10:5:5 in HFD and 10:1:5 in ND. To determine which nutrient is key to lowering blood estrogen levels, rats were orally administered carbohydrates (4 g of starch per kg of body weight), TG (2.5 mL of olive oil per kg of body weight)2, or protein (2 g of casein per kg of body weight), and we monitored their blood TG, FFA, glucose, and E2 levels (Fig. 1b). The amounts of nutrients administered were based on their content in HFD. Protein-administered rats did not show significant changes in blood E2 levels. TG-administered rats exhibited increased blood TG and E2 levels, as previously observed2. Carbohydrate-administered rats showed decreased blood E2 levels, alongside increased glucose and decreased FFA levels. Insulin decreases blood FFA levels20, and gastric gland epithelia produce estrogen in a FFA-dependent manner2. We thus analyzed the relationship between blood FFA and E2 levels. We found a positive correlation between them in rats at 1 h after carbohydrate administration, when blood glucose levels peaked (Fig. 1c). These data suggest that the insulin-induced reduction in blood FFA levels decreases blood E2 levels after meals.

Gastric estrogen enters the liver directly through the portal vein in high concentrations without being diluted in systemic blood, where it suppresses hepatic de novo lipogenesis11. Indeed, estrogen levels in portal blood are 2 to 10 times higher than in systemic blood6,14. However, after gastrectomy, estrogen levels in portal blood become similar to those in systemic blood, and blood estrogen levels remain unchanged even when blood TG levels are elevated by oral TG administration2,6,14. Therefore, elevated levels of blood estrogen in the portal vein, resulting from gastric estrogen, would play an important role in the regulation of hepatic lipogenesis. We then examined blood E2 levels in the portal and tail veins of fasted (deprived of food for 12 h) and postprandial (ND-fed: 2 h after a 0.5 h ND feeding) rats (Fig. 1d). In postprandial rats, blood glucose levels in the tail vein were higher compared to fasted rats, whereas their blood TG and FFA levels were lower than those in fasted rats, as observed in ND-fed rats in Fig. 1a. Blood E2 levels in the portal vein (fasted: ~200 pg/mL, ND-fed: ~120 pg/mL) were about 3.8 times those in the tail vein (fasted: ~53 pg/mL, ND-fed: ~30 pg/mL), regardless of feeding status. Blood E2 levels in ND-fed rats were about 0.6 times those in fasted rats in both veins. Therefore, gastric estrogen would maintain higher estrogen levels in portal blood than in systemic blood, and the postprandial decrease in blood lipid levels would decrease both portal and systemic blood estrogen levels. These data suggest that gastric estrogen plays a crucial role in suppressing hepatic lipogenesis and that the postprandial decrease in blood FFA levels increases hepatic lipogenesis by decreasing gastric estrogen production.

Intravenous injection of lipids partially recovers postprandially decreased blood Estrogen levels in males

To confirm that the postprandial decrease in blood estrogen levels was due to the decrease in blood FFA levels, we directly increased blood TG or FFA levels by intravenous injection (Fig. 2). Gastric parietal cells uptake FFA and generate energy with the help of heart-type fatty acid binding protein (H-FABP), which can process FFAs ranging from C10 to C182,22. On the other hand, certain types of cells in the stomach express GPR120 and CD36, which respond to FFAs of C14 or above and C20 or above, respectively2,23,24. These suggest that capric acid (C10-FFA) and lauric acid (C12-FFA) can serve as energy sources for gastric parietal cells without activating GPR120- or CD36-positive cells. We previously used C12-FFA in the in vitro E2 production assay using isolated gastric gland epithelia (Fig. 2a, left)2. However, C12-FFA was unsuitable for the injection study because of its low water solubility, so we considered using C10-FFA instead, which has high water solubility. Gastric gland epithelia were isolated from male rats aged 11 to 15 weeks after being deprived of food for 4 h. We incubated the epithelia with C10-FFA in the presence of testosterone and confirmed that the epithelia produced E2 in a C10-FFA concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2a, middle and right), so we used C10-FFA for the injection study.

Intravenous injection of lipids partially recovers postprandially decreased blood estrogen levels in males. a Male rats aged 11–15 weeks were deprived of food for 4 h. Isolated gastric gland epithelia from the rats (left) were incubated with capric acid (C10-FFA: 0, 250, 500 and 1000 µM) in the presence of testosterone (20 nM) at 37 ◦C for 1 h. Relative total E2 levels compared to the non-E2 producing control (C10-FFA: 0 µM) were determined (middle), and the relationship between C10-FFA concentrations and relative total E2 levels was analyzed (right). Bar: 50 μm. b and c Eight-week-old male rats were deprived of food for 12 h before the experiment. TG (2 mL of 20% soy oil emulsion per kg of body weight, b) or C10-FFA (2 mL of 150 mM capric acid [pH 7.8] per kg of body weight, c) was injected intravenously into postprandial rats (2 h after a 0.5 h ND feeding [bars]) (ND + TG or C10-FFA iv, blue) or control fasted rats (fasted + TG or C10-FFA iv, brown) (arrows, at 0 h). Blood TG, FFA, and E2 levels in the tail vein were measured before (ND-fed: at −2.5, −2, −1, 0 h; fasted: at 0 h) and at 0.25, 0.5. 1, 2, 3 h after injection. d Changes in blood FFA and E2 levels in fasted (brown) and postprandial (ND, blue) rats from before (at 0 h) to 0.25 h after the injection of TG or C10-FFA. Data are represented as mean ± s.d. n = 8. a R and P values determined by Pearson’s product-moment correlation with a 95% density ellipse. b–d P values were determined by a two-sided Student’s t-test between the indicated data sets. Raw data are provided in Supplementary Data 2.

Eight-week-old male rats were fasted for 12 h before the experiment. Postprandial (ND-fed: 2 h after a 0.5 h ND feeding) and control fasted rats were intravenously injected with TG (2 mL of 20% soy oil emulsion per kg of body weight)2 or C10-FFA (2 mL of 150 mM C10-FFA [pH 7.8] per kg of body weight). We monitored their blood TG, FFA, and E2 levels (Figs. 2b and c). When rats were injected with TG, blood TG, FFA, and E2 levels peaked immediately after the injection and returned to baseline levels 1 h later, regardless of their feeding conditions (Fig. 2b). Blood FFA and E2 levels in C10-FFA injected rats also peaked immediately after the injection but returned to baseline levels at a slower rate, while there were no significant changes in blood TG levels (Fig. 2c). Thus, blood E2 levels would be related to blood FFA levels, including those generated by the lipolysis of blood TG.

To investigate the effects of diet on the blood FFA-dependent increase in blood E2 levels, we compared the changes in blood FFA and E2 levels from before (0 h) to 0.25 h after the injection of TG or C10-FFA between ND-fed and fasted rats (Fig. 2d). While not significant, ND-fed rats showed smaller increases in blood E2 levels compared to fasted rats after either lipid injection. These data suggest that the postprandial decrease in blood FFA levels significantly contributes to the decrease in blood estrogen levels; however, other factors should also be considered.

Activation of gastric acid secretion decreases gastric Estrogen production in males

Gastric parietal cells use energy for acid secretion and estrogen production. Thus, when gastric acid secretion is stimulated, the energy available for producing gastric estrogen may decrease. Diet stimulates acid secretion through nerves and hormones25, so we investigated the effects of 15 hormones related to the stomach and metabolism, including autonomic neurotransmitters, on gastric estrogen production using isolated gastric gland epithelia (Fig. 3)2. We also examined the effects of an antacid, lansoprazole (LPZ)26.

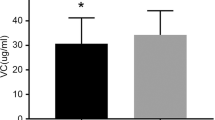

Activation of gastric acid secretion decreases gastric estrogen production in males. (a–c) Male rats aged 11–15 weeks were deprived of food for 4 h. Isolated gastric gland epithelia from the rats were cultured with testosterone (20 nM) and lauric acid (C12-FFA: 500 µM), either alone or with stomach- or metabolism-related hormones, or an antacid, lansoprazole (LPZ), at 37 °C for 1 h. Their relative E2 production levels, compared to those without hormones or LPZ, were determined. a Ghrelin, gastrin, histamine, and acetylcholine (ACh) decreased gastric E2 production. b Des-acyl-ghrelin, somatostatin, glucagon, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), cholecystokinin (CCK), cortisol, adrenaline, and LPZ increased gastric E2 production. c Insulin, leptin, and triiodothyronine (T3) had no effect on gastric E2 production. d Epithelia were cultured with gastrin, histamine, and ACh in the presence or absence of LPZ, and their relative E2 production levels were determined. Data are represented as mean ± s.d. n = 8. a–c P values, compared to the control hormone-free samples, were determined by Steel’s multiple comparison test (*: P < 0.05, **: P < 0.005). d P values between the indicated data sets were determined by a two-sided Student’s t-test. Raw data and actual P values are provided in Supplementary Data 3.

Gastric gland epithelia were isolated from male rats aged 11–15 weeks after being deprived of food for 4 h (neither fully fed nor fasting). The epithelia were cultured with a series of concentrations of hormones or LPZ in the presence of testosterone and C12-FFA. Epithelia cultured only with testosterone served as non-E2-producing controls to evaluate the E2 production during the culture2. We evaluated their relative E2 production levels, normalizing the E2 production levels without hormones to 1. E2 production was decreased by ghrelin, gastrin, histamine, and acetylcholine (ACh), all of which enhance gastric acid secretion (Fig. 3a)25. In contrast, des-acyl ghrelin, somatostatin, glucagon, GIP, GLP-1, CCK, cortisol, adrenaline, and LPZ increased E2 production; all, except cortisol, suppress gastric acid secretion (Fig. 3b)25,26,27,28,29,30. Insulin, leptin, and triiodothyronine (T3) did not affect E2 production (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, LPZ restored the decreased E2 production caused by gastrin, histamine, or ACh (Fig. 3d). These data indicate that the activation and suppression of gastric acid secretion lead to a decrease and an increase in gastric estrogen production, respectively.

Suppression of gastric acid secretion increases postprandially decreased blood Estrogen levels in males

We then investigated the effects of suppression of gastric acid secretion on blood estrogen levels in postprandial rats, which are active in gastric acid secretion. GLP-1 showed the most significant increase in gastric E2 production among the hormones examined that suppress gastric acid secretion (Fig. 3b). Thus, we used GLP-1 (hormone) and LPZ (drug) to suppress gastric acid secretion through different mechanisms25,26.

Eight-week-old male rats were fasted for 12 h before the experiment. Postprandial (ND-fed: 2 h after a 0.5 h ND feeding) rats and control fasted rats were intravenously injected with GLP-1 (2 mL of 12 ng/mL GLP-1 per kg of body weight) or LPZ (2 mL of 4 µM LPZ per kg of body weight). Their blood TG, FFA, and E2 levels were monitored (Fig. 4). GLP-1 and LPZ increased the decreased blood E2 levels in ND-fed rats 15 min after injection, whereas no significant changes were observed in blood E2 levels in fasted rats. On the other hand, blood TG and FFA levels did not show significant changes in either group of rats. These data suggest that suppression of gastric acid secretion increases the postprandially decreased blood estrogen levels.

Suppression of gastric acid secretion increases postprandially decreased blood estrogen levels in males. Eight-week-old male rats were deprived of food for 12 h. GLP-1 (2 mL of 12 ng/mL GLP-1 per kg of body weight, (a) or LPZ (2 mL of 4 µM LPZ per kg of body weight, (b) was injected intravenously into postprandial (2 h after a 0.5 h ND feeding [bars]) (ND + GLP-1 or LPZ iv, blue) and control fasted rats (fasted + GLP-1 or LPZ iv, brown) (arrows, at 0 h). Blood TG, FFA, and E2 levels in the tail vein were measured before (ND-fed: at −2.5, −2, −1, 0 h; fasted: at 0 h) and at 0.25, 0.5. 1, 2, 3 h after the injection. Data are represented as mean ± s.d. n = 8. P values were determined by a two-sided Student’s t-test between the indicated data sets. Raw data are provided in Supplementary Data 4.

Blood estrogen decreases after meals and activation of gastric acid secretion decreases gastric estrogen production in females

We showed that a postprandial decrease in blood FFA levels and the activation of gastric acid secretion reduce gastric estrogen production using male rats. Gastric parietal cells secrete estrogen in response to blood lipid levels, regardless of gender2. However, blood estrogen levels in females are higher than in males and fluctuate during their estrous cycle15,31. We then performed the key experiments using female rats in the metestrous phase, when blood estrogen levels are stable (Fig. 5). Estrous cycles were monitored using the vaginal impedance measurement technique32.

Blood estrogen decreases after meals and activation of gastric acid secretion decreases gastric estrogen production in females. (a) and (b) Eight-week-old female rats in the metestrous phase were deprived of food for 12 h. (a) Rats were fed ND ad libitum for 30 min (from − 0.5 to 0 h, bars). Blood TG, FFA, glucose, and E2 levels in the tail vein were measured before (−0.5) and at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 h after feeding (red). Data from ND-fed male rats in Fig. 1a were plotted for comparison (blue). (b) Rats were fed ND ad libitum for 30 min. Blood TG, FFA, glucose, and E2 levels in the tail vein and blood E2 levels in the portal vein were measured 2 h after feeding (blue). Fasted rats were used as control “pre-fed” rats (brown). (c) Comparison of blood E2 levels in the portal vein of male (Fig. 1d) and female rats. (d) Female rats aged 11 to 15 weeks in the metestrous phase were deprived of food for 4 h. Isolated gastric gland epithelia were cultured with testosterone (20 nM) and C12-FFA (500 µM), either alone or in the presence of gastrin (100 pg/ml), histamine (100 pg/ml), glucagon (40 pg/ml), GLP-1 (3 pg/ml), LPZ (1 nM), or insulin (100 pg/ml). Their relative E2 production levels, compared to those without hormones or LPZ, were determined. Data are represented as mean ± s.d. n = 8. (a–c) P values were determined by a two-sided Student’s t-test between the indicated data sets. (d) P values, compared to the control hormone-free samples, were determined by Steel’s multiple comparison test (**P < 0.005). Raw data and actual P values are provided in Supplementary Data 5.

We first examined the changes in blood estrogen levels in ND-fed female rats and compared them to those in male rats (Fig. 1a, ND) (Fig. 5a). Eight-week-old female rats in the metestrous phase were fasted for 12 h. The rats were fed ND ad libitum for 30 min, and their blood TG, FFA, glucose, and E2 levels were monitored. Blood E2 levels decreased after feeding, with increased glucose and decreased FFA levels, while blood TG levels showed a slight downward trend. These results are consistent with those observed in male rats, even though female rats exhibited higher blood E2 levels and lower blood TG levels compared to male rats. Next, we examined the blood E2 levels in the portal and tail veins of fasted (deprived of food for 12 h) and postprandial (ND-fed: 2 h after a 0.5 h ND feeding) female rats (Fig. 5b). Blood glucose levels in the tail vein were higher in postprandial rats than in fasted rats, while their blood TG and FFA levels were lower than those in fasted rats, as observed in ND-fed rats in Fig. 5a. Blood E2 levels in the portal vein (fasted: ~310 pg/mL, ND-fed: ~240 pg/mL) were about 4.5 times (fasted: ~4.2 times, ND-fed: ~4.8 times) those in the tail vein (fasted: ~74 pg/mL, ND-fed: ~50 pg/mL) under both feeding conditions. Blood E2 levels in ND-fed rats were about 0.73 times (portal vein: ~0.77 times, tail vein: ~0.68 times) those of fasted rats in both veins. These results are also consistent with those observed in male rats, albeit blood E2 levels in the portal vein were higher in female rats compared to male rats (Fig. 5c). Therefore, regardless of gender, blood FFA and E2 levels decrease after meals, and blood estrogen levels are higher in the portal vein than in the tail vein, although female rats show higher blood E2 levels and lower blood TG levels than male rats.

Finally, we examined the effects of hormones on gastric estrogen production in females. We used gastrin and histamine, which reduced gastric E2 production in males, as well as glucagon, GLP-1, and LPZ, which enhanced it, along with insulin as an ineffective control (Fig. 3). Female rats aged 11 to 15 weeks in the metestrous phase were deprived of food for 4 h. Gastric gland epithelia isolated from the rats were cultured with testosterone and C12-FFA, either alone or in the presence of the hormones or LPZ. We evaluated their relative E2 production levels, normalizing the E2 production levels without hormones to 1 (Fig. 5d). Epithelia cultured only with testosterone served as non-E2-producing controls. The concentrations of hormones and LPZ were determined based on the results obtained from male rats (Fig. 3). As observed in male rats in Fig. 3, gastrin and histamine decreased gastric E2 production, while glucagon, GLP-1, and LPZ increased it; insulin had no effect. Therefore, the activation and suppression of gastric acid secretion decrease and increase the production of gastric estrogen, respectively, in females as they do in males.

Discussion

We demonstrated that carbohydrate intake and the activation of gastric acid secretion decrease gastric estrogen production and blood estrogen levels in both male and female rats. Gastric parietal cells generate energy from FFA, including those lipolyzed from TG, and use it for estrogen production and acid secretion (Fig. 6a)2,33. Diets rich in carbohydrates stimulate insulin release and increase gastric acid secretion. Insulin lowers blood FFA levels20, though it does not directly affect gastric estrogen production (Fig. 3c). Thus, decreased blood FFA levels and increased gastric acid secretion after meals would lead to a decrease in gastric estrogen production (Fig. 6b, left). On the other hand, lipid intake raises blood TG levels and stimulates the secretion of hormones that suppress gastric acid secretion, such as GIP, GLP-1, and CCK2,21, leading to an increase in gastric estrogen production (Fig. 6b, right). Insulin and gastric estrogen directly enter the liver at high concentrations before being diluted in systemic blood, enhancing and suppressing hepatic de novo lipogenesis, respectively (Fig. 1d)11,16. The more lipid ingested, the less lipogenesis is required. Therefore, we propose that gastric estrogen, in conjunction with insulin, regulates hepatic lipogenesis based on the levels of ingested carbohydrates and lipids (Fig. 6).

Effects of diet and hormones on gastric estrogen production. (a) Gastric parietal cells produce estrogen and secrete acids using energy from lipids (FFA, including those lipolyzed from TG). (b) Carbohydrate intake (insulin) decreases blood FFA levels (upper left). Lipid intake, adrenaline, and cortisol increase blood lipid levels (upper right). Gastric acid-secreting hormones, such as those induced by food intake (gastrin, histamine, and ACh), decrease gastric estrogen production (lower left). Hormones that suppress gastric acid secretion, including those induced by lipid intake (GIP, GLP-1, and CCK) and fasting (des-acyl ghrelin, glucagon, and adrenaline), increase gastric estrogen production (lower right). Gastric estrogen goes directly to the liver and suppresses hepatic lipogenesis at high concentrations before being diluted in the systemic blood (bottom).

Conventional exercise, fasting, the newly introduced GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs), and low-carbohydrate diets are recommended for patients with fatty liver disease19,34,35. These therapies are considered to aid in the prevention or treatment of fatty liver by enhancing energy expenditure (exercise), limiting energy intake (fasting), suppressing appetite (GLP-1 RAs), decreasing insulin-induced lipogenesis from carbohydrates (low-carbohydrate diet), and/or utilizing pathways unrelated to gastric estrogen. In this study, we demonstrated that blood estrogen levels are high in fasted rats, decreasing after meals, particularly following carbohydrate intake (Fig. 1). Additionally, we found that glucagon (released during fasting)36, adrenaline (released during fasting and exercise)25,36, and GLP-1 enhance gastric estrogen production (Fig. 3). Therefore, these therapies may help reduce hepatic lipogenesis, at least in part, by increasing gastric estrogen secretion. In contrast, dietary habits that consistently lower blood FFA levels and increase gastric acid secretion- such as “carbohydrate snacking”- would continuously promote hepatic lipogenesis by persistently suppressing gastric estrogen production. Furthermore, hyperlipidemia and fatty liver are prevalent among the elderly9,19. Since gastric parietal cells and blood testosterone decrease with age, gastric estrogen production is expected to decrease as well17,18. A new subcategory of “gastric estrogen dysfunction” may be added to hyperlipidemia and fatty liver disease in the future. Therefore, this study will shed new light on the field of lipid metabolism, especially regarding the prevention and treatment of fatty liver disease.

Blood estrogen levels in females are higher than in males and fluctuate during their estrous cycle15,31. Indeed, blood E2 levels in both the portal and tail veins were higher in female rats than in male rats, and female rats showed lower blood TG levels than male rats (Fig. 5). However, in female rats, as in male rats, blood E2 levels decreased with a decrease in blood FFA levels after meals, and the activation of gastric acid secretion leads to a decrease in gastric estrogen production. Therefore, the effects of diets on gastric estrogen would essentially be the same, regardless of gender. However, since we used females in the metestrous phase, further investigation is required to understand how different estrous phases influence the regulation of gastric estrogen production in female rats.

There are still other questions that remain to be clarified. Firstly, the indirect effects of hormones on gastric estrogen production, including their crosstalk, should be investigated. Indeed, insulin did not affect gastric estrogen production “directly” (Fig. 3c) but decreased it “indirectly” by lowering blood FFA levels (Fig. 1). Secondly, it is crucial to understand how hormones influence aromatase activity and energy production in gastric parietal cells at the intracellular level. Gastrin, histamine, and ACh stimulate gastric acid secretion through phosphorylation pathways25, and phosphorylation both positively (Y361)37 and negatively (S118)38 regulates aromatase activity. Phosphorylation may also affect energy production in gastric parietal cells through H-FABP39. Thirdly, it is important to investigate the developmental and age-dependent changes in the regulation of gastric estrogen, as these changes influence aromatase levels in gastric parietal cells and blood testosterone levels18,40. Finally, studies using gastric parietal cell-specific aromatase knockout animals will genetically confirm this study and explore the role of gastric estrogen in hepatic lipogenesis and hyperlipidemia in live animals.

Methods

Animals

Wistar rats, purchased from Kiwa Laboratory Animals (Japan), were housed in an air-conditioned environment (24 ± 2 °C and 50–60% humidity) with 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 8:00 AM) and had ad libitum access to food (normal diet [ND, CE-2 diet, CLEA-Japan (Tokyo, Japan); carbohydrate: TG: protein = 10: 1: 5]) and water unless stated otherwise. In studies feeding a high-fat diet (HFD, D12451, Research Diets; carbohydrate: TG: protein = 10: 5: 5), the rats were fed a HFD for one week before the experiment to acclimate. In studies with female rats, we selected those in the metestrous phase, determined using the vaginal impedance measurement method with MK-10-B (Muromachi Kikai, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions32. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the protocol approved by the Wakayama Medical University Animal Care and Use Committee (approval number: 1104) and followed the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org).

Hormones and antacid

Ghrelin (334-43731), des-acyl ghrelin (332-44371), insulin (093-06471), glucagon (339-40981), leptin (120–06591), cholecystokinin (CCK, 333-41001), gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP, 331-41781), glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1, 333-43441), somatostatin (332-40231), gastrin (338-41431), histamine (088–00641) and acetylcholine (ACh, 011–00592) were purchased from FujiFilm (Tokyo, Japan). Triiodothyronine (T3, T2887), cortisol (H4001), and adrenaline (E4642) were purchased from Merck (Amsterdam, Netherlands). Lansoprazole (LPZ, 123–05861), a proton pump inhibitor, was purchased from FujiFilm.

Feeding study

Eight-week-old male or female (metestrous phase) rats were deprived of food for 12 h. The rats were fed ND (or HFD when indicated) ad libitum for 30 min (from − 0.5 to 0 h), and their blood samples were collected from the tail vein before (−0.5) and at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 h after feeding. In the experiments examining portal blood E2 levels, the rats were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation. After confirming deep anesthesia, blood was collected from the tail and portal veins. Rats with initial blood TG levels in the tail vein exceeding 200 mg/dL were excluded from the study.

Oral administration of carbohydrate, TG, and protein

Oral administration studies were performed as previously described, with slight modifications2. Eight-week-old male rats were deprived of food for 12 h. Carbohydrate (4 g starch [10 mL of 40% starch solution] per kg of body weight), TG (2.5 mL olive oil per kg of body weight), or protein (2 g casein [12.5 mL of 16% casein solution] per kg of body weight) were administered orally to rats using the intragastric gavage technique. Their blood samples were collected from the tail vein before (0) and at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 h after the administration. The amounts of carbohydrate, TG, and, protein administered were determined according to their content in HFD (carbohydrate : TG : protein = 10 : 5 : 5). Starch (191–03985) and casein (030-01505) were purchased from FujiFilm. Olive oil (Yoshida) was purchased from Yoshida Pharmaceutical Company (Tokyo, Japan). Rats with initial blood TG levels in the tail vein exceeding 200 mg/dL were excluded from the study.

Intravenous injection of TG, FFA, and LPZ

Intravenous injection studies were performed as previously described, with modified conditions2. Eight-week-old male rats were deprived of food for 12 h. TG emulsion (2 mL of 20% soy oil emulsion per kg of body weight; Intralipos Injection 20%, Otsuka, Tokyo, Japan), C10-FFA (2 mL of 150 mM capric acid [pH 7.8] per kg of body weight; D0024, Tokyo Chemical Industry, Tokyo, Japan), or LPZ (2 mL of 4 µM LPZ per kg of body weight) was injected intravenously into fasted rats or rats fed ND ad libitum for 30 min followed by 2 h rest. Blood samples were collected from the tail vein before (at 0 h [fasted] or at −2.5, −2, −1, 0 h [ND fed]) and at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 h after the injection. Rats with initial blood TG levels in the tail vein exceeding 200 mg/dL were excluded from the study.

In vitro gastric estrogen production assay

Gastric gland epithelia were isolated as previously described with slight modifications2. Male or female (metestrous phase) rats aged 11–15 weeks were deprived of food for 4 h. After euthanasia by isoflurane inhalation, the stomachs of the rats were removed, opened along the greater curvature, and washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After removal of the serosal muscle, the fundic region was cut into < 5 mm pieces and shaken in the chelating buffer (5 mM EDTA in PBS) supplemented with Tosyl-L-lysyl-chloromethane hydrochloride (TLCK, 147 ng/mL, 200-20141, FujiFilm) for 2 h on ice. The supernatant was changed with the dissociation buffer (54.9 mM D-sorbitol and 43.4 mM sucrose in PBS), and the tube was shaken vigorously for 2 min to dissociate epithelia from the mucosa. After centrifugation at 160 g for 10 min at 4 ºC, the pellet was dissolved in DMEM (044-32955, FujiFilm) and filtered through a 100 μm cell strainer (VCS-100, Azwan) to obtain isolated gastric epithelia. Isolated gastric gland epithelia were observed under an Eclipse Ti microscope equipped with Plan Fluor 10/0.30 lens and DS-Fi1 camera (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Image processing was performed with ImageJ 2 2.3.0 (National Institutes of Health).

The epithelia were then aliquoted and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in DMEM supplemented with testosterone (20 nM, T-1500, Sigma) and TLCK (147 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of lauric acid (C12-FFA, L0016, Tokyo Chemical Industry), capric acid (C10-FFA, D0024, Tokyo Chemical Industry), hormones, or a drug. Epithelia incubated in DMEM supplemented with testosterone and TLCK only were used as non-E2 producing controls, as FFA is required for the epithelia to produce E22. After incubation, E2 and phospholipid (PL) levels were measured in the epithelium-containing culture medium. Since PL amounts are proportional to cell membrane quantities, E2 levels were adjusted based on PL levels to account for variations in cell volume among aliquoted samples (“corrected total E2 levels”).

In the experiments to evaluate the use of C10-FFA by gastric parietal cells, the epithelia were aliquoted into four and incubated in DMEM supplemented with testosterone and TLCK in the absence or presence of C10-FFA (0, 250, 500, or 1000 µM) (Fig. 2a, see also Supplementary Data 2). We obtained “relative total E2 levels” by normalizing “corrected total E2 levels” to that of the non-E2 producing control (C10-FFA: 0 µM).

In the experiments investigating the effects of hormones or a drug on gastric estrogen production, we compared the levels of E2 produced (Figs. 3 and 5d, see also Supplementary Data 3 and 5). Epithelia were aliquoted into eight (Figs. 3a-c and 5d) or nine (Fig. 3d). Seven (former) or eight (latter) aliquots were incubated in DMEM supplemented with testosterone, TLCK, and C12-FFA (500 µM) in the absence and presence of hormones or a drug. An aliquot incubated in DMEM supplemented with only testosterone and TLCK served as a “non-E2 producing control”. “Relative total E2 level” consists of “E2 newly produced during incubation (E2 production level)” and “E2 already present before incubation (“relative total E2 level” of the “non-E2 producing control”)”. Then, “E2 production levels” were determined by subtracting the “relative total E2 level” of the “non-E2 producing control” from the “relative total E2 levels”. We obtained “relative E2 production levels” by normalizing “E2 production levels” to that of the hormone or drug-free control.

Measurement of TG, glucose, FFA, E2, and PL concentrations

Measurements of TG, E2, and PL concentrations were performed as previously described2. Plasma glucose and FFA concentrations were measured using a LabAssay Glucose and a NEFA C (FujiFilm) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistics and reproducibility

Data are mean ± s.d. P values for two groups were determined by a two-sided Student’s t-test. P values between multiple groups and a control group were determined by Steel’s multiple comparison test. R and P values were determined by Pearson’s product-moment correlation with a 95% density ellipse. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro ver. 16 (SAS Institute Japan, Tokyo, Japan). P values < 0.05 were considered to be significant. R values > 0.5 and < −0.5 were considered to be positively and negatively correlated, respectively. Every experiment was repeated multiple times with essentially the same results.

Data availability

The source data for the Figures are available in Supplementary Data 1-5. All other data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Tokarz, V. L., MacDonald, P. E. & Klip, A. The cell biology of systemic insulin function. J. Cell. Biol. 217, 2273–2289 (2018).

Ito, T., Yamamoto, Y., Yamagishi, N. & Kanai, Y. Stomach secretes Estrogen in response to the blood triglyceride levels. Commun. Biol. 4, 1364 (2021).

Simpson, E. R. et al. Aromatase—A brief overview. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 64, 93–127 (2002).

Simpson, E. R. Sources of Estrogen and their importance. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 86, 225–230 (2003).

Bracht, J. R. et al. The role of estrogens in the adipose tissue milieu. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 1461, 127–143 (2019).

Ueyama, T. et al. Gastric parietal cells: Potent endocrine role in secreting Estrogen as a possible regulator of gastro-hepatic axis. Endocrinology 143, 3162–3170 (2002).

Ozawa, M. et al. PET of aromatase in gastric parietal cells using 11 C-vorozole. J. Nucl. Med. 52, 1964–1969 (2011).

Patel, S., Homaei, A., Raju, A. B. & Meher, B. R. Estrogen: the necessary evil for human health, and ways to tame it. Biomed. Pharmacother. 102, 403–411 (2018).

Guetta, V. & Cannon, R. O. Cardiovascular effects of estrogen and lipid-lowering therapies in postmenopausal women. Circulation 93, 1928–1937 (1996).

Dhillon, S. S. & Belsham, D. D. Estrogen inhibits NPY secretion through membrane-associated Estrogen receptor (ER)-α in clonal, immortalized hypothalamic neurons. Int. J. Obes. 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2010.124 (2019).

Qiu, S. et al. Hepatic Estrogen receptor α is critical for regulation of gluconeogenesis and lipid metabolism in males. Sci. Rep. 1–12 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01937-4 (2017).

Newell-Fugate, A. E. The role of sex steroids in white adipose tissue adipocyte function. Reproduction 153, R133–R149 (2017).

Huss, J. M., Torra, I. P., Staels, B., Giguère, V. & Kelly, D. P. Estrogen-related receptor alpha directs peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha signaling in the transcriptional control of energy metabolism in cardiac and skeletal muscle. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 9079–9091 (2004).

Ueyama, T., Shirasawa, N., Ito, T. & Tsuruo, Y. Estrogen-producing steroidogenic pathways in parietal cells of the rat gastric mucosa. Life Sci. 74, 2327–2337 (2004).

Kobayashi, H., Yoshida, S., Sun, Y. J., Shirasawa, N. & Naito, A. Changes of gastric aromatase and portal venous 17β-estradiol during the postnatal development and estrus cycle in female rats. Endocrine 46, 605–614 (2013).

Uehara, K., Santoleri, D., Whitlock, A. E. G. & Titchenell, P. M. Insulin regulation of hepatic lipid homeostasis. Compr. Physiol. 13, 4785–4809 (2023).

Kanai, S., Hosoya, H., Ohta, M. & Miyasaka, K. Decreased hydrogen–potassium-activated ATPase (H+–K+-ATPase) expression and gastric acid secretory capacity in aged mice. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 45, 243–252 (2007).

Kobayashi, H., Shirasawa, N. & Naito, A. Age-related alterations of gastric mucosa and Estrogen synthesis in rat parietal cells. Histochem. Cell. Biol. 157, 195–204 (2022).

Sanyal, A. J. Past, present and future perspectives in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16, 377–386 (2019).

Ruud, J., Steculorum, S. M. & ning, J. C. B. Uuml. Neuronal control of peripheral insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism. Nat. Commun. 8, 1–12 (2017).

Chaudhri, O., Small, C. & Bloom, S. Gastrointestinal hormones regulating appetite. Philos. Trans. R Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 361, 1187–1209 (2006).

Matsuoka, S. et al. Water-Mediated recognition of simple alkyl chains by heart‐type fatty‐acid‐binding protein. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 1508–1511 (2015).

Hirasawa, A. et al. Free fatty acids regulate gut incretin glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion through GPR120. Nat. Med. 11, 90–94 (2005).

Drover, V. A. et al. CD36 mediates both cellular uptake of very long chain fatty acids and their intestinal absorption in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 13108–13115 (2008).

Engevik, A. C., Kaji, I. & Goldenring, J. R. The physiology of the gastric parietal cell. Physiol. Rev. 100, 573–602 (2020).

Der, G. An overview of proton pump inhibitors. Gastroenterol. Nurs. 26, 182–190 (2003).

Chen, C. Y. et al. Des-acyl Ghrelin acts by CRF type 2 receptors to disrupt fasted stomach motility in conscious rats. Gastroenterology 129, 8–25 (2005).

Miederer, S. E., Schepp, W., Dein, H. J. & Ruoff, H. J. Effect of glucagon on adenylate cyclase activity and acid production of isolated human parietal cells. Klin. Wochenschr 64, 746–749 (1986).

Pederson, R. A. & McIntosh, C. H. Discovery of gastric inhibitory polypeptide and its subsequent fate: Personal reflections. J. Diabetes Invest. 7, 4–7 (2016).

Sanders, D. J. A review: the agents and actions of sympathetic nerve and catecholamine inhibition of gastric mucosal function. Agents Actions 6, 385–388 (1976).

BUTCHER, R. L., FUGO, N. W. & COLLINS, W. E. & Plasma concentration of LH, FSH, prolactin, progesterone and Estradiol-17β throughout the 4-Day estrous cycle of the rat. Endocrinology 94, 1704–1708 (1974).

Bartoš, L. Vaginal impedance measurement used for mating in the rat. Lab. Anim. 11, 53–55 (1977).

Abumrad, N. A. et al. Endothelial cell receptors in tissue lipid uptake and metabolism. Circ. Res. 128, 433–450 (2021).

Yki-Järvinen, H., Luukkonen, P. K., Hodson, L. & Moore, J. B. Dietary carbohydrates and fats in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18, 770–786 (2021).

Nevola, R. et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists in Non-Alcoholic fatty liver disease: Current evidence and future perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 1703 (2023).

Kersten, S. The impact of fasting on adipose tissue metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Cell. Biol. Lipids. 1868, 159262 (2023).

Ghosh, D., Egbuta, C., Kanyo, J. E. & Lam, T. T. Phosphorylation of human placental aromatase CYP19A1. Biochem. J. 476, 3313–3331 (2019).

Miller, T. W. et al. Aromatase is phosphorylated in situ at serine-118. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 112, 95–101 (2008).

Nielsen, S. & Spener, F. Fatty acid-binding protein from rat heart is phosphorylated on Tyr19 in response to insulin stimulation. J. Lipid Res. 34, 1355–1366 (1993).

Kobayashi, H., Yoshida, S., Sun, Y. J., Shirasawa, N. & Naito, A. Postnatal development of gastric aromatase and portal venous estradiol-17β levels in male rats. J. Endocrinol. 218, 117–124 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank Yuta Yamamoto, Naoko Yamagishi and Keiko Ikemoto from the Kanai Laboratory for their assistance. This study was supported by Medical Research Support from Wakayama Medical University (Y.K.). We also acknowledge proofreading and editing by Benjamin Phillis at the Clinical Study Support Center at Wakayama Medical University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.K. conceived the project, designed the experiments, interpreted the results, wrote the manuscript, and prepared the figures. Y.O. and A.T. found the postprandial decrease in blood E2 levels. T.I. performed in vivo experiments using rats. Y.K. and T.I. performed in vitro experiments using isolated gastric gland epithelia. Y.K. and T.I. performed statistical analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ito, T., Ozaki, Y., Tanaka, A. et al. Carbohydrate intake and activation of gastric acid secretion decrease gastric estrogen secretion. Sci Rep 15, 10818 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95718-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95718-z