Abstract

Repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is a technique used to enhance motor learning in older adults. Some studies have shown that applying rTMS to the primary motor cortex (M1) and the cerebellum enhances motor learning. This study investigates the effects of M1 rTMS and cerebellar rTMS on motor learning in older adults. Seventy healthy older participants were randomly divided into M1, cerebellar rTMS, and sham rTMS groups. Participants completed the Serial Reaction Time Task (SRTT), while receiving 10 min of 10 Hz rTMS, with the sham group receiving inactive stimulation. Reaction time (RT) and error rate (ER) were recorded before, immediately, and 48 h post-task. RT and ER decreased immediately after the SRTT in all groups (P < 0.001). Both intervention groups showed greater online motor learning than the sham group (P < 0.05). Additionally, both intervention groups exhibited offline motor learning and learning consolidation with more significant changes in the cerebellar-rTMS group during lasting time (P < 0.03), whereas the sham rTMS group could not maintain motor learning (P > 0.05). The findings suggest that both M1 and cerebellar rTMS enhance motor learning in healthy older adults, with cerebellar rTMS being more effective in consolidating motor learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The growing population of older adults is a persistent global trend with significant implications across various sectors, especially healthcare1,2. According to the World Population Prospects, the number of people over age 60 years is expected to more than double by 20501. Therefore, the need for targeted interventions specifically designed for older adults is becoming increasingly important3. Aging is associated with a range of changes in motor function, voluntary movements, motor learning, and movement skills4, which can affect all daily activities4. Motor skill relearning or the acquisition of new motor skills is a critical aspect of rehabilitation for older adults, as it can significantly improve their quality of life5. Therefore, improving motor learning during rehabilitation is essential for maintaining functional independence in this population6.

Motor learning, as an adaptive and consistent change in motor behavior, is a complex process of the brain in response to practice or experience7. The serial reaction time task (SRTT) is a widely used paradigm for investigating motor learning, assessing the implicit learning of motor sequences8. Motor learning involves a widespread brain network including the motor cortex, premotor cortex, basal ganglia, and cerebellum9. The cerebellum and primary motor cortex (M1) are the key cortical areas in motor control, which undergo structural and functional changes in older adults10,11. The cerebellum is involved in fine-tuning motor commands, error detection, and movement adaptation12, while M1 is responsible for movement execution and consolidation of motor skills during both online (during practice) and offline (between practice sessions) phases of motor learning during SRTT13. In other words, the cerebellum plays a key role in procedural learning and tasks like the SRTT by optimizing motor coordination, timing, and sequence learning14,15. It fine-tunes responses through error correction and adaptation, enabling faster and more accurate reactions to repetitive patterns14,15. Beyond motor functions, the cerebellum contributes to implicit memory and detecting regularities, enabling subconscious pattern recognition in SRTT14,15. It works closely with the basal ganglia and motor cortex to integrate motor learning and cognitive processes, making it essential for acquiring and improving repetitive skills14,15. Some studies indicate that both gray and white matter volumes in these regions decline significantly with aging, resulting in deficits in motor learning deficits16,17,18. In the cerebellum, age-related degeneration impairs its ability to integrate sensory feedback for error correction, which is essential for acquiring new motor skills19. Similarly, in M1, structural atrophy and reduced plasticity impair the brain’s ability to encode and refine motor patterns20. The age-related neural changes in response to increased motor cognitive demands may impact the learning of novel, complex motor skills in older adults20,21,22. Therefore, it is important to develop an intervention that can enhance motor learning in older adults20.

In particular, repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) over M1 has been shown to enhance motor learning by increasing cortical excitability, which facilitates the encoding of motor memories23. Likewise, stimulation of the cerebellum has been shown to improve motor learning by modulating cerebellar-cortical pathways, thereby enhancing movement coordination and error correction24. A key factor in the efficacy of rTMS is the frequency of stimulation25. High-frequency rTMS (e.g., 10 Hz) has been demonstrated to enhance neural excitability and promote long-term potentiation (LTP)-like plasticity23. Then, it appears that 10 Hz rTMS is the effective frequency for both M1 and cerebellum for enhancing motor learning.

Generally, rTMS is safe, effective, and non-invasive with minimal side effects or adverse effects26. Some studies have reported the therapeutic benefits of rTMS over M1 on motor learning in older adults27,28, and other studies have indicated the improvement of motor learning following cerebellar rTMS24,29. However, it is unclear which brain areas targeted by rTMS produce a greater and more lasting effect on motor learning. With this background in mind, this study aims to compare how rTMS over the M1 and cerebellum prime motor learning during the execution of the SRTT in healthy older adults.

Accordingly, it was hypothesized that:

-

Both M1 and cerebellar rTMS will improve motor learning during (online) and after (offline) the SRTT in healthy older adults, as indicated by significant reductions in Reaction time (RT) and error rate (ER) compared to the sham rTMS group.

-

One of these approaches may be more effective than the other in reducing RT and ER in healthy older adults.

Materials and methods

Design

This study utilized a parallel, double-blind, randomized controlled trial design and received approval from the Human Ethics Committee at Semnan University of Medical Sciences in Semnan, Iran (IR.SEMUMS.REC.1401.137). The study was registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (www.irct.ir; IRCT20151228025732N73; 2022/10/10). Recruitment and follow-up took place from January 2023 to June 2023. Data collection occurred at the Neuromuscular Rehabilitation Research Center of Semnan University of Medical Sciences following the declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided informed consent before participating in the study.

Participants

Seventy-five healthy older adults were assessed based on the study’s inclusion and exclusion criteria. These participants were randomly assigned to three groups using a block randomization method: M1 rTMS (n = 23), cerebellar rTMS (n = 24), and sham rTMS (n = 23). Ultimately, 70 participants with a mean age of 64.85 ± 4.32 years completed the study. The sample size was calculated using Cohen’s table, based on the effect size determined from the first 15 participants. This allowed for the detection of the effect of rTMS with 95% confidence and a statistical power of 85%.

The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: older adults aged 60–75 years, right-handed, and willing to participate. Participants with abnormal neurological or psychological conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia, and dyslexia19; psychiatric health problems19; a history or presence of epilepsy30; metal implants or pacemakers in their body30; exposure to any brain stimulation affecting the central nervous system in the last three months19; use of any sedative drugs in the last two weeks19; any symptoms of forgetfulness and depression19; uncorrected vision and hearing disorders; severe perceptual and memory problems (scores of less than 21, on the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE))19; suffering from any musculoskeletal or rheumatoid condition affecting the range of motion in the right upper extremity19; and any contraindications for TMS, such as intracranial metal implantation19 were excluded. The included participants were then randomly assigned to three groups using a computerized random number generator: (1) M1 rTMS concurrent with SRTT, (2) Cerebellar rTMS concurrent with SRTT, (3) Sham cerebellar or M1 rTMS concurrent with SRTT. Finally, all 70 participants completed the entire program and were analyzed. Figure 1 illustrates the flowchart of the eligibility assessment process throughout the study.

rTMS protocol

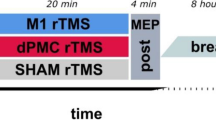

rTMS was performed using a magnetic stimulator with a figure-of-eight coil (70 mm in diameter) (MagSurve, MedinaTeb, Iran)24. The coil was positioned tangentially to the scalp, with the handle pointing superiorly in both conditions of M1 and cerebellar stimulation24. In this study, rTMS was applied at a frequency of 10 Hz for 10 min (6000 stimuli) at an intensity of 90% of the resting motor threshold (MT)29. The resting MT was determined by producing a peak-to-peak motor-evoked potential (MEP) of at least 50µV in the relaxed right abductor pollicis brevis (APB), which was measured by surface electromyography (EMG)31. To stimulate the left M1, rTMS was applied at the left M1 (C3), following the international 10–20 EEG system. In the cerebellar rTMS group, rTMS was applied over the right cerebellum (1 cm below the inion of the occiput bone and 1 cm on the inner side of the mastoid transversely in the back of the head). In the sham rTMS group, rTMS was randomly applied over the M1 or cerebellum. In the sham rTMS group, stimulation was turned off 1 min after starting, while the coils remained in place for 10 min and a sound similar to real rTMS was played. All groups received a single 10-minute rTMS session concurrently with the SRTT (Fig. 2).

Electromyography

The portable ME6000 surface EMG with MegaWin PC software was used to record the MEPs for determining the resting MT of the M1. After properly cleaning the skin, two surface electrodes were attached to the motor point of the right APB muscle (Ag-AgCl, 4-mm diameter, placed at the midpoint between the first metacarpophalangeal joint and carpometacarpal joint)30,32. A reference electrode was placed on the styloid process of the ulna32. Participants were seated in a comfortable chair in a semi-incumbent position30. The hands were in a resting pronated position30. We used single-pulse TMS to record resting motor thresholds (RMTs). The intensity of the M1 TMS was gradually increased until the 50µV MEP of the APB muscle was recorded on the monitor screen of the EMG to determine the MT31. 90% of this MT was considered as the intensity of rTMS during intervention for each participant. Each testing condition was recorded three times, and the average value was calculated for analysis30,32. Before the current study, the rTMS user intra- and inter-session reliability of rTMS-induced MEPs was assessed in a test-retest trial of 10 participants.

Serial reaction time task (SRTT)

In this study, the Color Matching Test (CMT), a custom-designed software program, was used to induce and assess motor learning with the SRTT. SRTT is a common method for assessing implicit motor learning that combines motor and cognitive components (Nissen & Bullemer, 1987)33. In the CMT software, colored squares repeatedly appeared in the center of a computer screen, with four possible colors: yellow, green, red, and blue. Each color was associated with a specific key on the computer keyboard (yellow- right shift key, red- C, green- M, blue- left shift key). Participants were instructed to keep their right index finger on the buttons and press the corresponding key as quickly and accurately as possible when a colored square appeared on the screen. The target-colored square would only disappear, when the correct key was pressed. To standardize the test conditions, participants were asked to return their index finger to the starting point on the keyboard, which was equidistant from all the relevant keys after pressing each key24. The participants completed two pre-test blocks, 8 blocks as the main training task, and finally two blocks 48 h after the completion of the main training, serving as a retention test. The second block of the pre-test was considered as the baseline data. Except for blocks 7 and 8, which were shown randomly, all other blocks followed a predetermined sequence. Each predetermined block consisted of 10 trials, with each trial containing 8 color cues in a specific sequence (e.g., Yellow-Red-Green-Yellow-Blue-Green-Yellow-Green.).

The RT and ER of performing each sequence in all three groups were recorded in the initial test before applying rTMS, in the main test when receiving rTMS, and in the retention test 48 h after applying this current. A decrease in RT and/or ER during the primary test (Block 10, referred to as Training Block 10) compared to Block 3 (referred to as Training Block 3), as well as during retests (Block 12, denoted as Post 12) compared to Block 2 (referred to as Pre 2), was used as a benchmark for assessing enhancements in online and offline motor learning, respectively. Moreover, the consolidation effect of learning was evaluated based on the persistence of RT or ER in Block 12 (referred to as Post 12) compared to Block 10 (referred to as Training Block 10). Participants were not given prior knowledge of the sequence order, so learning occurred implicitly across all test conditions.

Each participant completed all tests at a designated time early in the day and in the same environment. This approach was implemented to minimize the impact of fatigue and other potential confounding variables on motor learning.

Two physiotherapists were involved in performing the interventions. One of the physiotherapists, who was an expert in applying rTMS, carried out the interventions for all three groups. The other therapist, who was blinded to group assignments, assessed the outcome measures. The participants in all groups were also blinded to the experimental conditions.

Assessment of side effects or adverse effects of rTMS

Any side effects or adverse effects of rTMS were monitored using TMSens-Q, a questionnaire designed to report the unintended effects of rTMS at the end of each session34.

Statistical analysis

The collected data in the current study were analyzed using SPSS Version 24. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normal distribution of the data, and the results indicated that all data were normally distributed. One-way ANOVA was used to assess differences in the baseline values among the groups. This test was carried out to rule out any carry-over effects. Furthermore, a general linear mixed model (GLM) repeated measures ANOVA was performed to assess the main effects of group (i.e., M1 rTMS, cerebellar rTMS, and sham rTMS) and time (i.e., before, immediately, and 48 h post-intervention), as well as their interaction effects on motor learning. Moreover, changes in RT and ER were analyzed within groups using pairwise comparison tests. Post-hoc tests with Bonferroni correction will be performed where indicated. The Type I error (α) was set at 0.05.

Results

Demographic characteristics

The demographic and baseline data of the participants in each group are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences among the groups in terms of age, MMSE, baseline RT, and ER (P > 0.05). Moreover, the results indicated high intra-session and inter-session reliability of EMG for measuring the MT in the test and retest sessions. The intra-session ICCs of the test session ranged from 0.89 to 0.92, the ICCs of the retest session ranged from 0.90 to 0.92, and the inter-session ICCs ranged from 0.89 to 0.91. Additionally, the SEM and MDC were 0.06 and 0.12, respectively.

Comparing the effects of M1 and cerebellar rTMS to sham rTMS on RT and ER

The results of the GLM repeated measures ANOVA analysis are shown in Table 2. The findings indicated that the main effect of the group was significant for RT (P = 0.003). Furthermore, the main effect of “Time” was significant for all variables (P < 0.001). The group×time interaction effects were also significant for all variables (P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Post hoc analysis using Bonferroni correction showed a significant reduction in RT and ER between block 3 and block 10 and between Pre 2 and block 12 in the intervention groups (P < 0.05). This indicates online and offline learning (Fig. 3, a, b, d, e). In the sham rTMS group, there was a significant reduction in RT between block 3 and block 10, indicating online learning. However, there was no significant reduction in RT and ER between block 2 and block 12, indicating a lack of offline learning in the sham rTMS group (p > 0.05, Fig. 3c, f).

Reaction time of blocks during SRTT in M1-rTMS group, (b) reaction time of blocks during SRTT in cerebellar-rTMS group, (c) reaction time of blocks during SRTT in sham rTMS group, (d) errors number of blocks during SRTT in M1-rTMS group, (e) errors number of blocks during SRTT in cerebellar-rTMS group, (f) errors number of blocks during SRTT in sham rTMS group.

Comparing effects of M1 and cerebellar rTMS on RT and ER

There were significant differences in online and offline learning and consolidation effect of learning (RT and ER reduction) among groups, with more learning in the intervention groups (P < 0.05, Table 3; Fig. 4). Additionally, a consolidation effect of learning was shown in the intervention groups. The results showed a reduction in RT and ER, which lasted and even showed a trend toward more reduction, between block 10 and block 12 in the intervention groups (Fig. 3a, b, d, and e). However, more significant online and offline RT reduction and also consolidation effects of learning were shown in the cerebellar rTMS compared to the M1 rTMS group (p = 0.03, Fig. 4). On the other hand, the sham rTMS group did not show any consolidation effect (comparison between block 10 and block 12, Fig. 3c, f).

Reaction time of blocks during SRTT in the groups, (b) Errors number of blocks during SRTT in the groups; significant differences in RT and ER reduction among groups (online and offline learning and consolidation effect of learning), with more learning in the M1 rTMS and cerebellar rTMS groups (P < 0.05) and not any offline and consolidation effect of learning in sham group (P > 0.05).

All participants in this study completed the interventions with minimal side effects. Headache was a common side effect of cerebellar rTMS and M1 rTMS (cerebellar rTMS: 1.80 ± 0.59; M1 rTMS: 1.08 ± 0.33). However, the patients did not report any generalized seizures during or after stimulation.

Discussion

This study, for the first time, compares the effects of rTMS over the M1 and cerebellum on motor learning in older adults. The results showed that both M1 and cerebellar rTMS enhanced online motor learning during training and significantly improved offline learning and motor learning consolidation. Cerebellar rTMS was more effective than M1 rTMS, while the sham group was unable to maintain offline learning or consolidation, emphasizing the targeted efficacy of active rTMS.

One of the hypotheses of the current study was that both M1 and cerebellar rTMS improve motor learning during (online) and after (offline) the SRTT in healthy older adults, as compared to the sham rTMS group. The findings of the current study support this hypothesis and indicate the positive effects of both M1 and cerebellar rTMS groups as follows:

The effects of cerebellar rTMS on motor learning during (online) and after (offline) the SRTT

The findings of this study indicate that cerebellar rTMS significantly enhances both online and offline motor learning, as well as consolidating motor learning compared to the sham cerebellar rTMS in older adults. Although there have been no previous studies investigating the effects of cerebellar rTMS in conjunction with SRTT on motor learning in older adults, a previous study supports the findings of this study24,35. Koch et al. (2020) evaluated the effects of theta burst rTMS on modulating visuomotor adaptation in young healthy adults35. The results of the study showed that cerebellar rTMS had a strong bidirectional modulation on visuomotor adaptation task performance and improved motor learning35. Similar to the results of the current study, Koch et al. (2020) indicated that cerebellar rTMS accelerated visuomotor adaptation by reducing ER in response to a novel perturbation and maintained this improvement during a subsequent phase of re-adaptation35. The study by Celnik et al. (2015) also showed that rTMS can modulate connectivity between the cerebellum and the motor cortex36. This intervention has been found to impact motor, cognitive, and emotional processing and behaviors36.

By stimulating the cerebellum at the frequency of 10 Hz, neural activity in the deep cerebellar nuclei (DCN) is enhanced, partly through modulating the inhibitory output of Purkinje neurons, which project to the DCN37. This leads to a stronger and more precise output from the cerebellum to the ventral thalamus and subsequently to the M1 via the cerebello-thalamocortical pathway37. This enhanced communication improves the integration of sensory and motor information, facilitating the detection and correction of movement errors, which is critical for motor learning37. Additionally, 10 Hz rTMS induces synaptic plasticity within the cerebellum and associated pathways, supporting the refinement and retention of motor skills38. This process is likely especially important in the older population, where age-related declines in motor control and learning are associated with reduced neural plasticity39. The results of this study suggest that cerebellar rTMS, compared to the sham rTMS, may counteract the effects of aging, facilitating motor learning even in older adults.

The effects of M1 rTMS on motor learning during (online) and after (offline) the SRTT

The findings of the current study indicated that M1 rTMS can improve both online and offline motor learning and consolidate learning in older adults. Previous studies have also confirmed these findings and reported significant improvements in motor learning with M1 rTMS40,41. Hussain et al. (2021) found that compared to sham rTMS, M1 rTMS induced offline skill motor learning during mu peak and trough phases in healthy young adults40. Nojima et al. (2019) investigated the effects of static TMS over the right M1 and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) during an implicit motor task on online and offline motor learning in healthy adults41. They observed a reduction in RT immediately and 24 h after static TMS over M1, with significantly faster RTs in the M1 TMS group compared to the DLPFC TMS or Sham stimulation groups41. Rumpf et al. (2022) demonstrated that 10-Hz rTMS over the M1 significantly influences motor learning, particularly in terms of post-training offline consolidation42. While their study focused on the effects of 10-Hz rTMS on explicit motor learning in young adults, which differs from the population of the current study, it nonetheless confirms the positive and lasting impact of 10-Hz rTMS over M1 on motor learning. Kim et al. (2006) also indicated enhancement of motor learning performance and effective plastic changes with increasing motor performance accuracy following 10 Hz rTMS over M1 during SRTT in patients with stroke43. It seems that M1 plays a central role in movement execution and the modulation of motor performance and motor learning43. Studies have shown that M1 stimulation can enhance neural excitability and promote synaptic strengthening, which is essential for learning new motor tasks42,43.

Overall, rTMS over both M1 and cerebellum with frequencies above 1 Hz may suppress the inhibitory system by decreasing the activity of the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-ergic system44,45. This generally affects the motor system and improves offline motor learning44,45. Additionally, it seems that rTMS over both M1 and the cerebellum increases the firing rate of neurons and strengthens the newly formed associations among neurons, which can affect neural networks and the consolidation of sequence learning tasks44,45. Therefore, the application of one session of M1 and cerebellar rTMS can engrave new firing patterns in memory and facilitate offline motor learning processing as indicated in the current study44,45.

The second hypothesis of the current study was that one of these approaches may be more effective than the other in reducing RT and ER in healthy older adults. According to the findings of the current study, this hypothesis is confirmed as follows:

Comparing the effects of M1 and cerebellar rTMS on motor learning

The current study found that cerebellar rTMS was more effective than M1 rTMS in offline motor learning and consolidation of learning. While no studies have directly compared the effects of cerebellar and M1 rTMS on motor learning, some studies have compared cerebellar and M1 tDCS on motor learning and motor performance in healthy adults45. Ehsani et al. (2016) compared the effects of M1 and cerebellar a-tDCS on online and offline motor learning in healthy individuals45. They found that both M1 and cerebellar a-tDCS could enhance online and offline motor learning, but cerebellar a-tDCS had greater effects on offline learning and consolidation in healthy individuals45. These findings align with the results of the present study, as cerebellar rTMS significantly induced offline motor learning and consolidation of learning more than M1 rTMS in healthy elderly adults. Although a-tDCS and high-frequency rTMS have distinct neurophysiological mechanisms, they ultimately appear to produce similar neuroplasticity and motor learning effects.

One possible explanation for the greater efficacy of cerebellar rTMS compared to M1 rTMS is the distinct role of the cerebellum in motor learning. While both the cerebellum and M1 are crucial for motor learning, the cerebellum is particularly involved in error detection, adaptive control, and movement refinement36. Previous studies have shown that rTMS over the cerebellum activates Purkinje cells, induces long-term depression (LTD), modulates motor networks, and facilitates pathways to M136. During the SRTT, participants learn to respond as quickly as possible to sequentially presented visual stimuli35. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have demonstrated that the cerebellum plays an essential role in adapting to visuomotor tasks36. Cerebellar rTMS induces significant functional changes in the cerebellum-motor network, enhancing motor learning during early trials and contributing to consolidation36. Although M1 activity is critical for movement execution during motor learning46,47, the cerebellum plays a key role in retaining learned movements through repeated performance48. The stronger effects of cerebellar rTMS compared to M1 rTMS may be attributed to the cerebellum’s ability to integrate and process multimodal sensory inputs (vestibular, somatosensory, visual, and auditory) to refine motor planning49. This aligns with the findings of the current study, suggesting that the cerebellum may play a more prominent role than M1 in certain aspects of motor learning49. Additionally, Pauly et al. (2021) confirmed the clinically relevant benefits of cerebellar rTMS in enhancing motor thresholds in healthy individuals50. Although no study has directly compared the effects of cerebellar and M1 rTMS on motor learning, Kim et al. (2014) investigated the effects of rTMS over M1 and the supplementary motor area (SMA)51. Their findings indicated that while reaction time (RT) significantly decreased following rTMS over both the SMA and M1, the reduction in RT was significantly greater after SMA rTMS compared to M1 rTMS (p < 0.05) during implicit learning51. Similarly, the findings of the present study suggest that M1 rTMS has less long-term efficacy than cerebellar rTMS in reducing RT in older adults. The cerebellum and SMA share functional similarities, as both contribute to higher-order motor processes such as motor sequence learning, movement coordination, and error prediction. Both structures are involved in integrating information necessary for refining motor actions and optimizing performance. However, unlike the SMA, which is primarily engaged in movement planning and preparation, the cerebellum plays a more critical role in real-time error correction, sensory integration, and motor memory consolidation. In contrast to M1, which is essential for motor execution, the cerebellum’s influence extends beyond direct movement initiation. The cerebellum facilitates adaptive learning and offline consolidation, processes that enhance motor performance over time. The stronger effects of cerebellar rTMS in the present study suggest that its role in long-term motor learning may be more pronounced than that of M1, particularly in aging populations where motor retention deficits are more prevalent39.

The results of the current study suggest that rTMS over both the M1 and cerebellum may help counteract age-related change by enhancing neuroplasticity. The greater effectiveness of cerebellar rTMS compared to M1 rTMS on offline motor learning may reflect the key role of the cerebellum in adapting motor strategies over time to compensate age-related declines during motor retention and motor learning.

Limitations and suggestions for future studies

There were some limitations to the current study. At first, it assessed the effects of one session of rTMS on motor learning in elderly adults. Therefore, future studies should consider multiple sessions of rTMS applications, as they may be more effective for motor learning in this population. Secondly, due to time constraints, a 48-hour follow-up period was used in this study. It is recommended that future studies investigate the long-term effects of rTMS with longer follow-ups in older adults. Moreover, further studies are suggested to compare the lasting effects of rTMS on motor learning between young and older adults. Due to the neurophysiological differences between female and male older adults, the effects of rTMS on motor learning may vary between these groups. Therefore, investigating gender effects is crucial and requires further attention. Furthermore, it is suggested to compare the effectiveness of rTMS and tDCS over the M1 and cerebellum in future studies. Finally, the lack of neurophysiological measures such as fMRI is another limitation of this study. These assessments would be useful in understanding the possible mechanisms behind these observations and should be conducted in future studies.

Clinical implications

These findings may have significant clinical implications for motor learning, with a potential impact of cerebellar and M1 rTMS, especially cerebellar rTMS on rehabilitative procedures such as physiotherapy for older adults.

Conclusion

The findings of the current study indicated that both M1 and cerebellar rTMS significantly improve online and offline motor learning as well as the consolidation of learning in healthy older adults. The long-term effectiveness of cerebellar rTMS on motor learning was significantly higher than M1 rTMS, suggesting that cerebellar rTMS is more effective for motor learning consolidation in healthy older adults.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Béjot, Y. & Yaffe, K. Ageing population: A neurological challenge. Neuroepidemiology 52, 76–77. https://doi.org/10.1159/000495813 (2019).

Ismail, Z., Ahmad, W. I. W., Hamjah, S. H. & Astina, I. K. The impact of population ageing: A review. Iran. J. Public Health. 50, 2451–2460. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijph.v50i12.7927 (2021).

Pishkar Mofrad, Z., Jahantigh, M. & Arbabisarjou, A. Health promotion behaviors and chronic diseases of aging in the elderly people of Iranshahr*- IR Iran. Glob J. Health Sci. 8, 139–145. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v8n3p139 (2015).

Rueda-Delgado, L. M., Heise, K. F., Daffertshofer, A., Mantini, D. & Swinnen, S. P. Age-related differences in neural spectral power during motor learning. Neurobiol. Aging. 77, 44–57 (2019).

Monteiro, T. S., King, B. R., Adab, Z., Mantini, H., Swinnen, S. P. & D. & Age-related differences in network flexibility and segregation at rest and during motor performance. Neuroimage 194, 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.03.015 (2019).

Schrader, L. et al. Advanced sensing and human activity recognition in early intervention and rehabilitation of elderly people. J. Popul. Ageing. 13, 139–165 (2020).

Predel, C. et al. Motor skill learning-induced functional plasticity in the primary somatosensory cortex: a comparison between young and older adults. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12, 596438 (2020).

Trofimova, O., Mottaz, A., Allaman, L., Chauvigné, L. A. S. & Guggisberg, A. G. The implicit serial reaction time task induces rapid and temporary adaptation rather than implicit motor learning. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 175, 107297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2020.107297 (2020).

Albert, N. B., Robertson, E. M. & Miall, R. C. The resting human brain and motor learning. Curr. Biol. 19, 1023–1027 (2009).

De Zeeuw, C. I. & Ten Brinke, M. M. Motor learning and the cerebellum. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 7, a021683 (2015).

Monteiro, T. S. et al. Relative cortico-subcortical shift in brain activity but preserved training-induced neural modulation in older adults during bimanual motor learning. Neurobiol. Aging. 58, 54–67 (2017).

Andre, P. et al. The cerebellum monitors errors and entrains executive networks. Brain Res. 1826, 148730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2023.148730 (2024).

Psurek, F., King, B. R., Classen, J. & Rumpf, J. J. Offline low-frequency rTMS of the primary and premotor cortices does not impact motor sequence memory consolidation despite modulation of corticospinal excitability. Sci. Rep. 11, 24186. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-03737-3 (2021).

Janacsek, K. et al. Sequence learning in the human brain: A functional neuroanatomical meta-analysis of serial reaction time studies. NeuroImage 207, 116387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116387 (2020).

Baetens, K., Firouzi, M., Van Overwalle, F. & Deroost, N. Involvement of the cerebellum in the serial reaction time task (SRT) (Response to Janacsek et al). NeuroImage 220, 117114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117114 (2020).

Koppelmans, V., Hirsiger, S., Mérillat, S., Jäncke, L. & Seidler, R. D. Cerebellar Gray and white matter volume and their relation with age and manual motor performance in healthy older adults. Hum. Brain. Mapp. 36, 2352–2363 (2015).

Shigemori, K. et al. Motor learning in the Community-dwelling elderly during nordic backward walking. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 26, 741–743. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.26.741 (2014).

Berghuis, K. M. et al. Neuronal mechanisms of motor learning and motor memory consolidation in healthy old adults. Age. 37, 9779. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-015-9779-8 (2015).

Samaei, A., Ehsani, F., Zoghi, M., Hafez Yosephi, M. & Jaberzadeh, S. Online and offline effects of cerebellar transcranial direct current stimulation on motor learning in healthy older adults: a randomized double-blind sham-controlled study. Eur. J. Neurosci. 45, 1177–1185. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.13559 (2017).

Stewart, J. C., Tran, X. & Cramer, S. C. Age-related variability in performance of a motor action selection task is related to differences in brain function and structure among older adults. Neuroimage 86, 326–334 (2014).

MacLullich, A. M. et al. Size of the neocerebellar vermis is associated with cognition in healthy elderly men. Brain Cogn. 56, 344–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2004.08.001 (2004).

Drumond Marra, H. L. et al. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation to Address Mild Cognitive Impairment in the Elderly: A Randomized Controlled Study. Behav. Neurol. 287843, (2015). https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/287843 (2015).

Censor, N. & Cohen, L. G. Using repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation to study the underlying neural mechanisms of human motor learning and memory. J. Physiol. 589, 21–28 (2011).

Torriero, S., Oliveri, M., Koch, G., Caltagirone, C. & Petrosini, L. Interference of left and right cerebellar rTMS with procedural learning. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 16, 1605–1611. https://doi.org/10.1162/0898929042568488 (2004).

Anil, S., Lu, H., Rotter, S. & Vlachos, A. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) triggers dose-dependent homeostatic rewiring in recurrent neuronal networks. PLoS Comput. Biol. 19, e1011027 (2023).

Noh, J. S., Lim, J. H., Choi, T. W., Jang, S. G. & Pyun, S. B. Effects and safety of combined rTMS and action observation for recovery of function in the upper extremities in stroke patients: A randomized controlled trial. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 37, 219–230 (2019).

Yamanaka, K. et al. Effect of parietal transcranial magnetic stimulation on Spatial working memory in healthy elderly persons–comparison of near infrared spectroscopy for young and elderly. PLoS One. 9, e102306. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0102306 (2014).

Ma, S. R., Jeon, M. C., Yang, B. I. & Song, B. K. Effect of 1 hz low frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on cerebral activity and recovery on upper limb motor function in chronic stroke patients. J. Magn. 24, 758–762 (2019).

Sasegbon, A., Smith, C. J., Bath, P., Rothwell, J. & Hamdy, S. The effects of unilateral and bilateral cerebellar rTMS on human pharyngeal motor cortical activity and swallowing behavior. Exp. Brain Res. 238, 1719–1733 (2020).

Matamala, J. M. et al. Motor evoked potentials by transcranial magnetic stimulation in healthy elderly people. Somatosens. Mot. Res. 30, 201–205. https://doi.org/10.3109/08990220.2013.796922 (2013).

George, M. S. & Belmaker, R. H. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in clinical psychiatry. (2007).

Capozio, A., Ichiyama, R. & Astill, S. L. The acute effects of motor imagery and cervical transcutaneous electrical stimulation on manual dexterity and neural excitability. Neuropsychologia 187, 108613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2023.108613 (2023).

Nissen, M. J. & Bullemer, P. Attentional requirements of learning: evidence from performance measures. Cogn. Psychol. 19, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(87)90002-8 (1987).

Giustiniani, A. et al. A questionnaire to collect unintended effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation: A consensus based approach. Clin. Neurophysiol. 141, 101–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2022.06.008 (2022).

Koch, G. et al. Improving visuo-motor learning with cerebellar theta burst stimulation: behavioral and neurophysiological evidence. Neuroimage 208, 116424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116424 (2020).

Celnik, P. Understanding and modulating motor learning with cerebellar stimulation. Cerebellum 14, 171–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-014-0607-y (2015).

Langguth, B. et al. Modulating cerebello-thalamocortical pathways by neuronavigated cerebellar repetitive transcranial stimulation (rTMS). Neurophysiol. Clin. Neurophysiol. 38, 289–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucli.2008.08.003 (2008).

Lin, Y. C. et al. Baseline Cerebro-Cerebellar functional connectivity in afferent and efferent pathways reveal dissociable improvements in visuomotor learning. Front. Neurosci. 16, 904564. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.904564 (2022).

Gooijers, J. et al. Aging, brain plasticity, and motor learning. Ageing Res. Rev. 102, 102569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2024.102569 (2024).

Hussain, S. J. et al. Phase-dependent offline enhancement of human motor memory. Brain Stimul. 14, 873–883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2021.05.009 (2021).

Nojima, I. et al. Transcranial static magnetic stimulation over the primary motor cortex alters sequential implicit motor learning. Neurosci. Lett. 696, 33–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2018.12.010 (2019).

Rumpf, J. J., May, L., Fricke, C., Classen, J. & Hartwigsen, G. Interleaving motor sequence training with high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation facilitates consolidation. Cereb. Cortex. 30, 1030–1039 (2020).

Kim, Y. H. et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation–induced corticomotor excitability and associated motor skill acquisition in chronic stroke. Stroke 37, 1471–1476 (2006).

Casula, E. P. et al. Cerebellar theta burst stimulation modulates the neural activity of interconnected parietal and motor areas. Sci. Rep. 6, 36191. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36191 (2016).

Ehsani, F., Bakhtiary, A. H., Jaberzadeh, S., Talimkhani, A. & Hajihasani, A. Differential effects of primary motor cortex and cerebellar transcranial direct current stimulation on motor learning in healthy individuals: A randomized double-blind sham-controlled study. Neurosci. Res. 112, 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neures.2016.06.003 (2016).

Kobayashi, M. Effect of slow repetitive TMS of the motor cortex on ipsilateral sequential simple finger movements and motor skill learning. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 28, 437–448. https://doi.org/10.3233/rnn-2010-0562 (2010).

Hardwick, R. M., Rottschy, C., Miall, R. C. & Eickhoff, S. B. A quantitative meta-analysis and review of motor learning in the human brain. Neuroimage 67, 283–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.11.020 (2013).

Herzfeld, D. J. et al. Contributions of the cerebellum and the motor cortex to acquisition and retention of motor memories. Neuroimage 98, 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.04.076 (2014).

Manto, M. et al. Consensus paper: roles of the cerebellum in motor control–the diversity of ideas on cerebellar involvement in movement. Cerebellum 11, 457–487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-011-0331-9 (2012).

Pauly, M. G. et al. Cerebellar rTMS and PAS effectively induce cerebellar plasticity. Sci. Rep. 11, 3070 (2021).

Kim, Y. K. & Shin, S. H. Comparison of effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation on primary motor cortex and supplementary motor area in motor skill learning (randomized, cross over study). Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8, 937. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00937 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Neuromuscular Rehabilitation Research Center and Clinical Research of Semnan University of Medical Sciences for providing facilities for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Fatemeh Ehsani, Rasool Bagheri, and Shapour Jaberzadeh. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Saeid Khanmohammadi and all authors commented on previous versions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khanmohammadi, S., Ehsani, F., Bagheri, R. et al. Compared motor learning effects of motor cortical and cerebellar repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation during a serial reaction time task in older adults. Sci Rep 15, 12447 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95859-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95859-1