Abstract

Accurate modeling of satellite clock bias (SCB) is critical for enhancing high-precision positioning capabilities. Existing approaches, such as semiparametric adjustment models and neural networks, address the nonlinearity and non-stationarity of SCB time series, as well as potential distortions from trend and noise component overlap. However, these methods encounter practical limitations, particularly in the selection of kernel functions for semiparametric models and the initialization of parameters for neural networks. To overcome these challenges, this paper introduces a novel integrated model called the Semi-LFA-Informer (SLFAI) model. Moreover, this model combines semiparametric techniques with optimized self-attention neural networks and is applied to predict SCB for BDS-3. Its performance is compared with other models, including quadratic polynomial (QP), spectral analysis (SA), and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks. The comparison is focused on prediction stability and accuracy. The experimental results show that the proposed method can not only effectively solve the problem of the generalization ability, but also significantly enhance the computational efficiency and accuracy. The SLFAI model achieves average prediction accuracies exceeding 0.15 ns, 0.25 ns, and 0.35 ns for 3-hour, 6-hour, and 12-hour forecasts, respectively, Meanwhile, compared with the other three models, The SLFAI model shows an average prediction accuracy improvement of approximately 53.6%, 59.4%, and 43.5% for the 3-hour, 6-hour, and 12-hour forecasts, respectively, representing a new approach to acquiring high-quality SCB.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background and motivation

With the widespread application of global positioning system (GPS) and other satellite navigation systems in various fields, the demand for high-precision positioning is growing rapidly. Real-time precise point positioning (PPP) is an important positioning technology that can provide centimeter-level accuracy and is widely used in aviation, navigation, autonomous driving, precision agriculture, and other fields1,2. However, the accuracy and reliability of real-time PPP largely depend on the accurate prediction of satellite clock bias (SCB)3. SCB is the deviation between the satellite clock and the reference clock, and its changes directly affect the propagation time of satellite signals, thereby impacting positioning accuracy. Therefore, improving the accuracy of SCB prediction is crucial for enhancing the performance of real-time PPP.

Related results

Real-time PPP mainly relies on the state space representation (SSR) provided by monitoring and assessment centers (ACs), as well as the broadcast ephemeris. Then it is restored to acquire real-time satellite orbits and satellite clock bias products. Although the real-time restoration of precise SCB is sufficiently accurate for real-time users4, the timeliness and completeness of real-time SCB are easily affected by the latency and instability of the internet caused by transmission interruptions5. At the same time, a timing error of 1 ns can result in a distance error of up to 3 dm. In addition, while the accuracy of both rapid and final precision SCB products offered by various ACs can reach 0.1 nanosecond (ns) (http://www.igmas.org/Product/Zp/zzzc/cate_id/33.html), their respective delays of 17 h and 12 days impede real-time applications. Therefore, there is a critical need to explore methods to enhance the quality of real-time SCB products to meet the timeliness and completeness requirements6,7.

Currently, numerous researchers have proposed various SCB prediction models, such as the quadratic polynomial (QP) model8,9, grey model (GM)10,11, and spectral analysis (SA) model12,13. A comprehensive analysis reveals that while these models have distinct advantages, they also exhibit limitations. The modeling process of the QP model is simple, but it can cause serious cumulative errors over time. In addition, the forecasting performance of the GM depends on the exponential moving average coefficient of the series, while the SA model requires sufficient prior information. The interaction and dependence among SCB parameters, periodic terms, outliers, and systematic errors are common in SCB models, making it difficult to obtain the optimal parameters. In response, researchers have developed a semiparametric SCB model that segments SCB into parametric components, assigns periodic terms to nonparametric components, and categorizes outliers as residuals. This model, which simultaneously considers both parametric and nonparametric components, effectively accounts for periodic term corrections14,15,16,17. used a semiparametric model to correct the dynamic error of the SCB series, which mitigated the impact of nonlinear factors and improved the accuracy of prediction. However, subsequent researches have indicated that the choice of kernel function and bandwidth parameters critically influences the accuracy of parameter estimation in semiparametric models. In addition, inconsistencies in the periodicity of different satellite clocks may lead to overfitting or underfitting phenomena17,18. Consequently, the selection of kernel functions in semiparametric models can lead to biased estimates, indicating that SCB sequences from various satellites might require distinct kernels for accurate modeling, which affects their generalizability.

In addition to linear components, SCB encompasses complex nonlinear factors. To mitigate the impact of these nonlinearities, numerous researchers have implemented neural network algorithms19,20. employed a long short-term memory (LSTM) algorithm to predict BDS-2 ultrarapid SCB, enhancing prediction accuracy by 50% for a 6-hour interval. Similarly21, utilized a bidirectional long short-term memory (BiLSTM) model to forecast BDS SCB, achieving superior outcomes compared to traditional models. However, these models are based on serial structures of recursive neural networks22, and encounter several limitations: they are incapable of parallel processing, failing to fully exploit the computational capabilities of graphics processing units (GPUs), which results in significant time consumption. Additionally, the process of sequential data extraction and backward transmission may cause information loss, complicating the extraction of deeply hidden features in high-density datasets such as SCB, thereby challenging the network training process. Furthermore, common neural network practices like random initialization of weights, setting of thresholds, and gradient descent for network training can lead to slow convergence and issues with local minima22, hindering the achievement of stable SCB results.

The potential consequences resulting from inaccurate SCB prediction

Inaccurate SCB prediction can have significant consequences across various industries23. In aviation, even minor errors in SCB can lead to substantial discrepancies in aircraft navigation systems, potentially causing flight delays, increased fuel consumption, and in extreme cases, safety hazards. For instance, data from previous incidents have shown that navigation errors due to SCB inaccuracies have led to an average delay of 15 min per flight, resulting in significant economic losses for airlines. In the maritime industry, precise SCB is essential for ensuring the safe navigation of ships, especially in congested waterways or during adverse weather conditions. Inaccuracies here can lead to collisions or grounding incidents. Similarly, in the field of autonomous vehicles, reliable SCB prediction is vital for accurate positioning, which is fundamental to the safe operation of these vehicles. A study conducted in 2022 reported that SCB inaccuracies contributed to a 10% increase in the error rate of autonomous vehicle positioning systems.

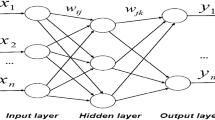

The aforementioned limitations of the semiparametric and neural network models can significantly impede the delivery of timely and stable forecasting results in practical scenarios. To deal with these problems, this paper proposes a combination model that combines a semiparametric adjustment model with a self-attention neural network. First, it uses a semiparametric estimation method to correct system errors based on periodicity, obtaining estimates of parametric and nonparametric components and fitting residuals. Then, the dot-product calculation of self-attention neural networks (Transformer) is optimized to improve the computational efficiency and space occupancy rate through sparsity optimization (Informer). An improved Levy Firefly algorithm (LFA) is utilized to determine the parameters of the sparse self-attention model (LFA-Informer)15,24. Subsequently, the LFA-Informer is used to model and forecast the fitting residuals of semiparametric, then compensates the semiparametric forecast results with these predictions by linear compensation method. Finally, a comprehensive experimental analysis is conducted with Semi-LFA-Informer (SLFAI), and the results are evaluated by stability and forecasting accuracy.

The organization of this paper is structured as follows: Sect. "Semi-LFA-Informer Model" describes the construction of the semiparametric clock bias model and its compensatory forecasting method. Section "Neural Network Optimization for Compensation Prediction" details the neural networks employed for compensation forecasting, along with their optimization strategies. Section "Results and analysis" is dedicated to the validation and analysis of the SLFAI model, utilizing experimental data from multiple perspectives. Section "Conclusion" summarizes the experimental results of the SLFAI.

Semi-LFA-Informer model

In this section, we initially outline the establishment and resolution of the semi-parametric SCB model. Subsequently, we introduce the linear compensation approach for combined forecasting.

Semiparametric components of the SCB prediction model

Due to the influence of satellite orbits, space environment, and various perturbative forces on in-orbit satellites, periodic terms are added to the conventional QP model to establish an SA model for mitigating the impact of these disturbances on SCB prediction. The SA model can be formulated as follows:

where \({L_i}\) represents the SCB at epoch \({t_i}\); \(i\) is the epoch number; \({a_0}\), \({a_1}\), and \({a_2}\) represent the phase, clock rate (frequency), and clock drift, respectively; \({t_0}\) is the reference epoch of the SCB; \({\Delta _i}\) represents the model residual; and \(n\) represents the number of SCB. \(p\) is the number of periodic terms; \(k\) is the order of the periods; and \({A_k}\), \({B_k}\), and represents the amplitude and frequency of the corresponding periodic term, respectively. In addition to the periodic errors in the SA model, the SCB is also affected by factors such as satellite orbital errors, mechanical modeling system biases and the quality of the SCB; none of these factors can be parameterized and lumped into residuals. Therefore, by considering the periodic term, this paper incorporates these nonparametric errors into the nonparametric component with \(s({t_i})\). The semiparametric SCB prediction model is established as follows:

\(L={({L_1}\;\;{L_2}\;\; \cdots \;\;{L_n})^T}\), \({b_i}=[1\;\;{t_i} - {t_0}\;\;\;{({t_i} - {t_0})^2}\;\;\sin (2\pi {f_{i1}}{t_i}+{\varphi _{i1}})\;\; \cdots \;\;\sin (2\pi {f_{ip}}{t_i}+{\varphi _{ip}})]\), \(B={[{b_1}\;\;{b_2}\;\; \cdots \;\;{b_n}]^T}\), \(X={[{a_0}\;\;{a_1}\;\;\;{a_2}\;\;{A^{\prime}_{i1}}\;\; \cdots \;{A^{\prime}_{ip}}]^T}\), \(S={[{s_1}\;\;{s_2}\;\; \cdots \;\;{s_n}]^T}\), \({s_i}=s({t_i})\), \(\Delta ={[{\Delta _1}\;\;{\Delta _2}\;\; \cdots \;\;{\Delta _n}]^T}\). Thus, Eq. (2) can be expressed in matrix form:

Parameter Estimation

To obtain the optimal estimation of the parametric and nonparametric components in Eq. (3), a three-step method is employed. First, assuming that \(\hat {X}\) is known, based on \(\{ {t_k},{L_k} - {B_k}X\} _{{k=1}}^{n}\) we introduce the kernel weight function \({W_k}(t)=W({t_k}:{t_1},\,{t_2}, \cdots ,\,{t_n})\) to estimate the kernel of the nonparametric component \(S({t_i})\), i.e.,

The details of the kernel weight function are calculated as follows:

In Eq. (5), \(K( \cdot )\) is an arbitrarily chosen kernel function, and \(h\) is the window width typically selected by the generalized cross-validation (GCV) method16. There are three commonly used kernel functions. in this paper, the sixth-order kernel weight function Kernel2 is chosen as \(K( \cdot )\)14,18: Kernel1, the Quartic kernel, Kernel2, the Sixth-order kernel, and Kernel3, the Probability Density kernel, are respectively represented by Eq. (6), Eq. (7), and Eq. (8).

Considering that the least squares (LS) method is a widely used approach for linear regression estimation, parameter \({\hat {X}_h}\) can be estimated by LS with the obtained information \(W\) by introducing

Substituting \({\hat {X}_h}\) into Eq. (4), we obtain the estimate of the nonparametric component \(S({t_i})\):

According to processes Eq. (6) to Eq. (10), the accuracy of the nonparametric component estimates is strongly influenced by the estimations of the parametric component, the kernel weight function, and the window width. The estimation of the parametric component and the nonparametric component are interdependent and affect each other. To improve the accuracy, Eq. (10) can be iterated into Eq. (4), again with LS to obtain parameter \(\hat {X}\) as follows:

Substituting \({\hat {X}_{2 h}}\) into Eq. (10), we can obtain the third estimation of the nonparametric component:

From processes Eq. (11) to Eq. (12), the estimated values of the observations as \(\hat {L}=B{\hat {X}_{2 h}}+{\hat {S}_{3 h}}\hat {=}H(h)L\) can be obtained, where \(H(h)\) is the hat matrix.

Fitting residual prediction

The semiparametric kernel estimation method can effectively reduce systematic errors during the forecasting process. As shown in Eq. (11) and Eq. (12), the calculation of the kernel function has a significant impact on the estimation of signal \(\hat {S}\) and determines the applicability of the kernel weight function. Furthermore, the penalty factor window width of the kernel function may introduce estimation bias in separating the nonparametric component, leading to issues such as insufficient fitting residuals or overfitting, ultimately affecting the forecasting results of the semiparametric model. To fully utilize and extract the useful information in the fitting residuals, the fitting residual sequence is subtracted from the fittings of the semiparametric SCB prediction model \(Vn\) as follows:

where \(L\) represents the SCB series, \(Ln\) is the fitted value of the semiparametric SCB prediction model, and \(Vn\) is the fitting residual.

Through selecting appropriate thresholds and weights, neural networks can estimate any continuous function, which gives them a unique advantage in fitting the complex nonlinear characteristics of residuals. Self-attention neural networks provide a new approach to address these issues with a serial structure. Compared to traditional neural network algorithms, self-attention neural networks can effectively capture long-distance dependencies between sequences. Researches have replaced the serial structure with the Transformer model, which achieved significant results in computer vision and natural language processing. Therefore, this paper employs a cascading combination of two prediction models, where the predicted values of the semiparametric model are compensated by the predicted values of the neural network model. This approach yields the final SCB prediction result, as shown in Eq. (14):

In Eq. (14), \({L_{comb}}\) represents the predictions from the combined prediction model, \({L_{semi}}\) denotes the predictions from the semiparametric model, and \({V_{net}}\) refers to the neural network fitting residuals.

Neural network optimization for compensation prediction

In this section, we explore the optimization techniques for neural networks used in compensation prediction. We begin with an examination of the sparse optimization scheme of the Transformer neural network, followed by an analysis of the optimization of neural network parameters.

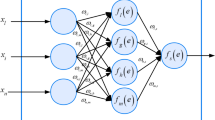

Sparse optimization scheme of the transformer neural network

At present, LSTM and BiLSTM, which are dependent on sequential data architectures, are widely used neural network models for satellite clock bias (SCB) prediction. To avoid the drawbacks of the sequential structure in these models, we chose Transformer as the semiparametric model for compensation15,19. In the Transformer neural network, the self-attention mechanism allocates weights to samples. In this framework, the sequence input to the model undergoes an initial linear transformation, producing three matrices of identical dimensions: the query (\({\varvec{Q}}\)), key (\({\varvec{K}}\)), and value (\({\varvec{V}}\)) matrices. Subsequently, these matrices are processed through scaled dot-product attention. The functional expression can be expressed as follows:

where \(softmax( \cdot )\) is the activation function and \(d\) represents the dimension of the input sequence.

The self-attention mechanism utilizes a standard dot product calculation method, in which each element of the input sequences forms a connection with the entire sequence, resulting in the time complexity of each attention layer being related to the length of the input sequence as \(O({N^2})\). As the length of the input data sequence increases, the computational complexity grows exponentially. However, in applications, part of the elements is significantly related to only a few other elements, and their connections are relatively unimportant to most other elements. These unimportant connections consume considerable memory and computational resources. To reduce computational complexity, a sparsity optimization scheme can be adopted for self-attention calculations, using the dot product results of a few queries \({\varvec{Q}}\) and keys \({\varvec{K}}\) to dominate the complexity.

For this reason, sparsity can be achieved by evaluating the importance of the target sequence vectors and performing subsequent dot product calculations based on the evaluations. This approach allows for selective focus on the most relevant parts of the sequence, which reduces the attention mechanism’s focus to the most significant elements and ignores or lowers the weight to the less relevant parts, thus helping to optimize the computational procedure. This method helps in managing and significantly lowering the computational load and memory requirements without compromising accuracy, especially for long sequences, making the model more efficient:

Selecting a constant sampling factor \(s\) as a hyperparameter to compute \({a_1}={N_Q}\ln ({N_K})\), and set \({a_2}=s\ln ({N_K})\) under the control of \(s\) .

Sampling \({a_1}\) dot product pairs for the \({\varvec{K}}\) vectors randomly, form a new key matrix \(\overline {{\varvec{K}}}\), and calculate the sampled score \(\overline {{{\varvec{s}}{\varvec{c}}{\varvec{o}}{\varvec{r}}{\varvec{e}}}}\) as follows:

The sparsity score \({\varvec{M}}\) for each row is computed as follows:

The matrix is scored, the top \({a_2}\) \({q_i}\) vectors are selected, and a new matrix \(\overline {{\varvec{Q}}}\) is formed. The self-attention mechanism after sparsity optimization is represented as follows:

The remaining \({q_i}\) does not participate in the dot product operation. After probabilistic sparsification of the \({\varvec{Q}}\) matrix to obtain \(\overline {{\varvec{Q}}}\), the computational complexity is reduced from \(O({N^2})\) to \(O(N\log N)\) with exponential decreases. This enables the model to extract weighted feature information from a large amount of redundant information for computation.

Optimization of the neural network parameters

To address the unstable prediction results of neural networks in SCB forecasting, this section focuses on optimizing parameters of Informer. Sparsity optimization improves the computational efficiency and spatial complexity of the network, whereas, it neglects the selection of the initial parameters. Neural networks have strong nonlinear sequence fitting and prediction capabilities. However, the typically utilized random initialization of weights and thresholds along with learning methods based on gradient descent could lead to issues such as slow convergence or becoming trapped in local optima. In the short-term forecasting of SCB, which has timeliness, stability, and accuracy requirements. It is easily limited by the random initialization of weights and thresholds of the neural network. The FA model is known for its excellent global optimization capability and fast convergence. Moreover, it does not rely on the gradient information of the objective function. Therefore, the hyperparameter optimization of the FA algorithm is chosen for SCB forecasting.

During the optimization of the FA model, the convergence speed and accuracy are influenced by the set parameters. For parameter setting, too large of a value will accelerate convergence but reduce accuracy, while too small of a value may converge to suboptimal values and prevent the identification of the global optimum. To address this issue, the Levy flight algorithm is introduced to complement the position updates of the traditional FA model with a random search. Levy flight is a random search method that follows the Levy distribution, and is characterized by a mixed search pattern of short and occasionally long distances. This flight pattern enhances local neighborhood searches around the optimal solution and explores the solution away from the algorithm space. By increasing population diversity and expanding the search range, it resolves issues such as becoming trapped in local optima and premature convergence in swarm intelligence algorithms24. As shown in Fig. 1, when updating the position of fireflies with FA, the Levy flight algorithm is used to generate random step sizes. The random step sizes generated by the Levy algorithm can not only satisfy the need for convergence, but also have a certain probability of generating larger step sizes to escape suboptimal values and converge to the global optimum.

Based on the above discussion, this paper combines semiparametric and neural network approaches and enhances model computational efficiency. Initially, the semiparametric kernel estimation method is employed to eliminate systematic errors from the clock error sequences. Subsequently, the optimized neural network is utilized to fit the residuals obtained from the semiparametric estimation, thereby compensating for the semiparametric forecast values. This approach circumvents information loss due to kernel function selection in semiparametric methods. Besides, the proposed method addresses the instability issues associated with single neural network forecasting models. The framework of the proposed method is shown in Fig. 2. (Table 1)

Results and analysis

In this section, we first analyzed the necessity of the algorithm and the effectiveness of the optimization strategy, and then verified the performance of the proposed method for SCB prediction. The experiments were conducted with precise SCB products provided by the German Research Centre for Geosciences on February 21, 2023. In this work, the prediction accuracy is evaluated by two indices: the standard deviation (STD) for stability, and the root mean square (RMS) for Accuracy.

Influence of semiparametric kernel function

First, the effect of the semiparametric kernel method on the extraction of systematic errors is analyzed. The QP and SA methods (with two effective main periodic correction terms added, where the first and second important main periods for the GEO, IGSO, and MEO satellites are 12 h and 24 h; 24 h and 12 h; and 12.911 h and 6.444 h, respectively)1,25, at the same time the semiparametric model using the kernel2 function (Semi-K) is used to fit the SCB series. The fitting residuals of the three models and the nonparametric component curve extracted by the semiparametric model, as shown in Fig. 3. The fitting residuals of the SA model are somewhat improved compared to those of the QP model, with certain corrections with periodic terms introduced. However, there still exist certain periodic characteristics in the separated nonparametric, which indicate the added periodic terms in the model are not optimal for all satellites, leading to significant systematic errors in the SCB series. This demonstrates the limitations of the SA model, whereas the semiparametric model can effectively identify and separate nonparametric components and solve the physical parameters of the satellite clocks, thereby enhancing the fitting and prediction performance.

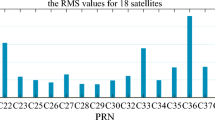

To compare the impact of kernel function selection on the prediction results, a semiparametric SCB prediction model with three different kernel functions was tested for an short-term prediction of 12 h. The RMS of the prediction errors for the three kernel functions and the QP and SA models are presented in Fig. 4.

The RMS of the SA model is closed and slightly better than that of the QP model. The average RMS of the semiparametric model with the three kernel functions is significantly better than that of the SA model, indicating that the semiparametric kernel method can effectively separate systematic errors based on periodic corrections. However, due to the varied periodic characteristics among satellites and inconsistencies in SCB data quality, kernel functions are not universally applicable to all satellites, leading to estimation biases.

As shown in Table 2, the average prediction accuracy using three different functions is 0.65 ns, 0.58 ns, and 0.76 ns. Among them, kernel2 exhibits the best overall performance. However, its average prediction accuracy on IGSO hydrogen clocks is 0.51 ns, which is lower than the 0.42 ns and 0.38 ns achieved by kernel1 and kernel3, respectively. Due to space limitations, only the test results of C20, C24, and C43 are given. From the result, it can be found that the kernel2 function performs the best on average. However, in the results of satellite C20, the prediction accuracy of kernel1 and kernel3 are 0.40 ns and 0.45 ns, respectively, while that of kernel2 is 0.87 ns. For C24 and C43, the prediction accuracy of both kernel1 and kernel2 is approximately 0.5 ns, but kernel3 performs poorly, with an accuracy at the nanosecond level. This indicates that the choice of kernel function has a significant impact on the results of semiparametric prediction. Inappropriate selection of the kernel function can lead to prediction biases and insufficient fitting. Therefore, it is necessary to apply neural networks to compensate for the prediction of semiparametric models for extracting information of fitting residuals.

Sparse effect analysis of the transformer neural network

To verify the computational performance of the sequence neural network LSTM models, the traditional self-attention transformer models, and the sparse optimization self-attention Informer models, this section will analyze the theoretical time-space complexity and actual time consumption of these models in SCB forecasting. Table 3 provides information on theoretical training complexity, space occupancy, and prediction time complexity of the three models. According to statistical analysis, the training time for the Transformer model increases quadratically with the length of the input sequence. In contrast, the Informer model outperforms the Transformer in spatial and temporal complexity. Regarding prediction speed, the Transformer and LSTM models have similar time complexities, but the Informer model surpasses both, requiring less time and significantly faster processing speeds.

Moreover, a comparative analysis of these three models was conducted, and Fig. 5 shows the training time and prediction time results for the three models (this study employs the PyTorch deep learning framework, i9-CPU, and Nvidia GTX3090 24 GB GPU server).

According to Fig. 5(a), if the amount of input epochs of the encoder is less than 168, the runtimes of the Informer and LSTM models are approximately the same within 3 min; both are smaller than that of the Transformer model. When the number of input epochs ranges from 168 to 336, the training time of the Informer model slightly increases. As the number of input epochs increases to 336 or more, the training time of the Informer model rapidly increases. This is attributed to the self-attention mechanism requiring full connectivity attention computation between all the input positions and other positions, resulting in increased computational complexity. Moreover, the model contains multiple layers and multi-head attention mechanisms, and each layer requires parameter updates and backpropagation, further increasing the computational load. Therefore, the training time of the Informer model begins to increase. For the prediction stage in Fig. 5(b), the Informer model can generate prediction sequences in a single step without increasing the computational burden, thereby enhancing the prediction efficiency and stability and outperforming the LSTM and Transformer models. In short-term SCB prediction, considering both training and prediction computation times, the Informer model exhibits a significant advantage.

Selection of the neural network parameter optimization

To compare the convergence speed and effectiveness of parameter optimization algorithms, this study employed three optimization methods to validate the feasibility of LFA. Figure 6 presents the fitness convergence curves of the LFA algorithm, FA, and SSA (sparrow search algorithm) over 100 iterations.

Figure 6 shows that LFA has certain advantages over FA and shows even more significant performance improvements compared to the SSA. Within 50 iterations, both the fitness values of the FA and SSA methods converge to within 0.025 ns, while the fitness of LFA has already converged to within 0.023 ns. By the 85th iteration, the convergence effects of the FA and SSA algorithms tend to stabilize, with fitness values of 0.024 ns and 0.0245 ns, respectively. The results indicate that the FA algorithm outperforms the SSA algorithm. Besides, the LFA algorithm outperforms both the FA and SSA algorithms in terms of convergence speed and effectiveness. This suggests that the LFA algorithm can provide more reliable initial thresholds and weights for neural networks, thereby laying a better foundation for model training.

Stability verification

All the satellites, including the MEO rubidium clocks, MEO hydrogen clocks, IGSO hydrogen clocks, and GEO hydrogen clocks, are included in the experiment except for C35, which has missing data. The commonly used QP model, SA model, LSTM model, and proposed SLFAI model are used for comparative analysis.

In the experiment, we select the first 12 h of SCB with a sampling time of 5 min as the input for the models. Then, the trained models were used for SCB prediction for 3 h, 6 h, and 12 h (Lv et al., 2020). The stability of the predictions was evaluated based on the STD. Figure 7 provides a chart comparing the stability of the four models at different prediction times.

Figure 7 shows that in the 3 h prediction, the prediction stability of the SLFAI model is relatively worse for C43, with an STD value of 0.24 ns, and the stabilities of the other satellites are relatively better than 0.2 ns on average. As the prediction time increases to 6 h, the stability of the SLFAI model predictions for C43 does not decrease with increasing prediction time, and the STD returns to the same level as that of the other models. According to the 12 h prediction time, the prediction stability of the SLFAI model is relatively stable and better than 0.5 ns for all satellites. Additionally, Table 4 has shown that compared with the other three models, the average prediction stability of 3 h, 6 h, and 12 h forecasting of the SLFAI has improved by approximately (46.1%, 53.3%, 41.7%), (53.9%, 57.1%, 36.8%) and (72.3%, 71.9%, 47.1%), respectively. The stability advantage of the proposed SLFAI model is more pronounced than that of the other three models, with the highest average stability. This result indicates a significant advantage in stability for all three forecast durations of the short-term SCB prediction.

Accuracy assessment

To further compare the prediction accuracy of different models for SCB prediction, we calculated the accuracy statistics with RMS for the four models over three prediction schemes. The statistics for all satellites are presented in the Fig. 8.

Figure 8 shows that in the 3 h scheme, the SLFAI model maintains RMS of less than 0.5 ns, and the average performance is superior to the other three models. For the prediction results for 6 h in Fig. 8, the prediction accuracy of C23 and C43 are worse than those of all the other satellites with all the prediction models. This suggests that the quality of the SCB sequence for these two satellites might be poor, with the removal of outliers significantly impacting the prediction models. However, in the 12 h prediction, the SLFAI model consistently exhibited excellent prediction performance for all satellites, with the lowest RMS values achieved in the four models. The results in Table 5 show that the proposed SLFAI model can achieve better prediction accuracy with more reasonable modeling. Compared with the other three models, the average prediction accuracy of the 3 h, 6 h, and 12 h forecasting has improved by approximately (53.6%, 59.4%, 43.5%), (56.3%, 60.4%, 38.2%) and (71.2%, 70.6%, 44.8%), respectively. It is evident that as the forecasting duration extends from 3 h to 12 h, and the number of prediction epochs increases, the prediction accuracy advantage of the SLFAI model becomes more pronounced. This indicates that the QP and SA models accumulate significant errors as the number of prediction epochs increases, whereas the SLFAI model is more effective than the LSTM model in controlling error accumulation.

Conclusion

In this paper, the SLFAI model is introduced as an innovative approach that integrates semiparametric techniques with neural network methodologies to enhance the prediction accuracy of SCB. In the SLFAI framework, limitations such as the generalization capability of the kernel function, as well as the randomness and slow convergence speed of neural networks, have been optimized. The SLFAI model is well-suited to the high-density, long-sequence, and complex nonlinear characteristics of SCB, enabling effective extraction of global features. Experimental results show that the Levy flight strategy is employed to reduce the iteration count and improve the quality of hyperparameter optimization in the FA. In the later stages of the iteration, the fitness value reached 0.024, significantly outperforming SSA and FA. The improvements in the search strategy based on Levy flight have broad applicability and offer new insights for other optimization algorithms. Additionally, Moreover, the computational efficiency of the Transformer model is enhanced through the sparse dot product process. These improvements collectively bolster the stability and responsiveness of the neural network for compensating the semiparametric model, thus enhancing the ability of the SLFAI model for the SCB prediction. Furthermore, The SLFAI model compensates for the missing information caused by kernel function selection and effectively improves the stability and accuracy of SCB prediction. It demonstrates strong performance in forecasting across 3 h, 6 h, and 12 h intervals, achieving stability of 0.07 ns, 0.12 ns, and 0.18 ns, and the accuracy of 0.12 ns, 0.20 ns, and 0.32 ns, respectively. These results indicate that the method not only excels in 3-hour predictions but also delivers even more substantial benefits over the longer 12-hour forecast period, showcasing its superior effectiveness in controlling cumulative errors.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The authors thank the GFZ for providing accessible data for this study. and can be downloaded from http://ftp.gfz-potsdam.de/pub/GNSS/products/mgnss/.

References

Ai, Q., Xu, T., Sun, D. & Ren, L. The prediction of BeiDou satellite clock bias based on periodic term and starting point deviation correction. Acta Geodaetica Cartogr. Sin. 45 (S2), 132–138 (2017).

Panfilo, G. & Tavella, P. Atomic clock prediction based on stochastic differential equations. Metrologia 45 (6), 108–120 (2008).

Zheng, Z., Dang, Y., Lu, X. & Xu, W. Prediction model with periodic item and its application to the prediction of GPS satellite clock bias. Acta Astronomica Sinica. 51 (1), 95–102 (2010).

Han, T. Fractal behavior of BDS-2 satellite clock offsets and its application to real-time clock offsets prediction. GPS Solutions. 24 (5), 947–973 (2020).

He, L., Zhou, H., Wen, Y. & He, X. Improving short term clock prediction for BDS-2 real-time precise point positioning. Sensors 19 (12), 2762–2762 (2019).

Liu, Z., Chen, X., Liu, J. & Li, C. High precision clock bias prediction model in clock synchronization system. Math. Probl. Eng. 2016 (1), 1–6 (2016).

Yang, Y., Mao, Y. & Sun, B. Basic performance and future developments of BeiDou global navigation satellite system. Satell. Navig. 1 (1), 273–304 (2020).

Wang, Q. Time prediction accuracy for a space clock. Metrologia 40 (3), 265–269 (2003).

Yao, Y., Yuanxi, Y., Heping, S. & Jiancheng, L. Geodesy discipline: progress and perspective. Acta Geodaetica Cartogr. Sin. 49 (10), 1243–1251 (2020).

Huang, F., Chen, Y., Li, T., Yuan, H. & Shan, X. A satellite clock bias prediction algorithm based on grey model and chaotic time series. Acta Electronica Sinica. 47 (07), 1416–1424 (2019).

Lv, D., Ou, J. & Yu, S. Prediction of the satellite clock bias based on MEA-BP neural network. Acta Geodaetica Cartogr. Sin. 49 (8), 993–1003 (2020).

Mao, Y., Wang, Q. X., Hu, C., Yang, H. Y. & Yu, W. X. New clock offset prediction method for BeiDou satellites based on inter-satellite correlation. Acta Geod. Geoph. 54 (1), 35–54 (2019).

Pan, X., Huang, W. K. & Zhao, W. ZH.,etal. Research on short-term prediction accuracy of BDS-3 clock bias based on BiLSTM model. Acta Geodaeticaet Cartogr. Sinica. 53 (1), 65–78 (2024).

Pan, X., Wang, L. V. Y., Luo, Y. & Xu, J. Research of the location and valuation of gross error based on semi-parametric adjustment model. Geomatica Inform. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 41 (11), 1421–1427 (2016).

Pan, X., Zhao, W., Huang, W., Zhang, S. & Jin, L. Short-term prediction of satellite clock bias based on improved self-attention model. J. Chin. Inert. Technol. 31 (11), 1092–1101 (2023).

Li, W., Xiong, Y., Lei, X., Ren, Q. Y., Pan, X. & R., & Abnormal data detection and process by using BDS satellite offset semiparametric adjustment model. Acta Geodaetica Cartogr. Sin. 49 (1), 55–68 (2020).

Qiu, F. et al. Global ionospheric TEC prediction model integrated with semiparametric kernel Estimation and autoregressive compensation. Chin. J. Geophys. 64 (9), 3021–3029 (2021).

Yan, X., Li, W., Yang, Y. & Pan, X. BDS satellite clock offset prediction based on a semiparametric adjustment model considering model errors. Satell. Navig. 1 (1), 15–21 (2020).

Pan, X. et al. Ultra-short-term prediction method for BDS-3 clock offset by combined semi-parameteric and improved BiLSTM models. J. Chin. Inert. Technol. 32 (10), 985–993 (2024).

Wen, T., Ou, G., Tang, X., Zhang, P. & Wang, P. A novel long Short-Term memory predicted algorithm for BDS Short-Term satellite clock offsets. Int. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2021 (1), 1–16 (2021).

He, S., Liu, J., Zhu, X., Dai, Z. & Li, D. Research on modeling and predicting of BDS-3 satellite clock bias using the LSTM neural network model. GPS Solut. 27 (3), 108 (2023).

Siami-Namini, S., Tavakoli, N. & Namin, A. S. The performance of LSTM and BiLSTM in forecasting time series. IEEE International conference on big data (Big Data), 2019(1), 3285–3292(2019). (2019).

Cai, C., Liu, M., Li, P., Li, Z. & Lv, K. Enhancing satellite clock bias prediction in BDS with LSTM-attention model. GPS Solutions. 28 (2), 92 (2024).

Alshmrany, S. Adaptive learning style prediction in e-learning environment using levy flight distribution based CNN model. Cluster Comput. 25 (1), 523–536 (2022).

Zhou, P. et al. Periodic variations of BeiDou satellite clock offsets derived from multi-satellite orbit determination. Acta Geodaetica Cartogr. Sin. 44 (12), 1299–1306 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The experimental data utilized in this manuscript are publicly accessible and can be downloaded from http://ftp.gfz-potsdam.de/pub/GNSS/products/mgnss/.

Funding

This research is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 42174010, NO.41874009), Natural Science Funds of Hubei Province (No. 2023AFB435) and State Key Laboratory of Geodesy and Earth’s Dynamics, Innovation Academy for Precision Measurement Science and Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. SKLGED2024-3-3).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Lihong Jin, Wanzhuo Zhao, Xiong Pan, Cai Mao, Ruan Xiaoliand Qingsong Ai wrote the main manuscript text, All authors reviewed the manuscript. Xiong Pan proposed the shortcomings and solution of the semiparametric model. Wanzhuo Zhao and Mao Cai conducted experiments under the supervision of Lihong Jin, Qingsong Ai and Xiaoli Ruan contributed to validate the method and helped to improve this work. All authors were involved in writing the paper, literature review, and discussion of results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jin, L., Zhao, W., Pan, X. et al. Combining semiparametric and machine learning approaches for short-term prediction of satellite clock bias. Sci Rep 15, 11880 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95876-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95876-0