Abstract

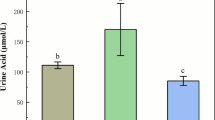

In recent years, gout resulting from uric acid metabolism disorders has led to significant economic losses in goose production. The intestine is a vital organ crucial for uric acid metabolism. Hydroxypropyl starch (HPS) is a resistant starch modified from natural starch, which can enhance intestinal health as a dietary ingredient fiber. In this study, 240 30-day-old Yangzhou geese with similar body weights were divided into three groups: The control group (CG) received a basal diet + 5% corn starch; the hydroxypropyl starch group (HPS) and the sodium urate group (SU) were given a basal diet + 5% hydroxypropyl starch. The experiment lasted for 21 days, and the SU group was administered 30 mg of sodium urate per day during the last 4 days of the study. The results indicated that the level of uric acid in the HPS group was 56.6 µmol/L, significantly lower than that in the CG group (70.8 µmol/L) and the SU group (129.7 µmol/L). The morphological findings revealed that the ileum of the CG group and the SU group exhibited varying degrees of damage, while the HPS group maintained complete structure. The villus height and the ratio of villus height to crypt depth in the HPS group were significantly higher compared to those in the CG and SU groups, while the crypt depth was significantly lower than that in the SU group. A total of 1462 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified at the transcriptome level. GO and KEGG functional enrichment analyses indicated that the DEGs were significantly enriched in the Brush border membrane, Brush border, PPAR signaling pathway, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, and other related processes. Subsequent analysis revealed that HPS up-regulated the expression of genes associated with intestinal function (such as SLC5A12 and SLC5A8), structure (including NR5A2, IPMK), and uric acid metabolism (PDZK1). The accuracy and reliability of transcriptome sequencing data were confirmed by RT-qPCR. In this study, we systematically demonstrated that HPS can improve intestinal morphology and reduce serum uric acid levels, emphasizing its potential as a dietary supplement for geese.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Factors including viral infection, nutritional imbalance, or impaired kidney function can result in uric acid metabolic disorder in poultry, leading to avian gout1. Uric acid is primarily produced in the liver, intestines, and blood vessels endothelium2. The intestinal tract is the primary organ for the extrarenal metabolism of uric acid3, and approximately 1/3 of the uric acid produced per day is metabolized through the intestinal tract4.

The small intestine is the body’s most essential digestive organ. As a part of the small intestine, the ileum contains a wealth of intestinal microorganisms5. Research shows some bacteria can directly participate in uric acid metabolism6. The intestinal flora of gout patients is significantly different from that of healthy people7 and leads to changes in intestinal structure8. The complete intestinal structure underlies the function of uric acid transporters. Previous studies have demonstrated that ABCG2 serves as a high-capacity uric acid transporter, with abundant expression found in the brush border membrane of small intestinal epithelial cells, playing a significant role in uric acid excretion 9. SLC16A9 also has similar functions 10, while SLC2A9 is involved in uric acid reabsorption 11. Additionally, some proteins, such as PDZK1 and CARMIL MAF, are indirectly involved in regulating serum uric acid levels12.

Resistant starch (RS) refers to starch that cannot be directly digested and absorbed by the body. As a type of dietary fiber, it positively affects intestinal conditions13. Microorganisms can ferment it as a substrate to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which provide energy for epithelial cells, aiding in the metabolism of uric acid and enhancing the integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier14,15. Hydroxypropyl starch (HPS) is a resistant starch that is artificially modified from natural starch16. Studies indicate that dietary fiber can lower serum uric acid levels by decreasing the absorption of adenine from food17,18. Previous research has shown that HPS leads to significant changes in intestinal flora19 and may influence plasma cholesterol concentration by producing propionic acid20. However, there is currently no research on the direct effect of HPS on uric acid metabolism.

In this study, we evaluated the effect of HPS on geese through intestinal morphology and serum uric acid levels, while also investigating the molecular mechanism of HPS on intestinal health and uric acid metabolism in geese using transcriptomics. This research provides a scientific basis for HPS as a feed additive for geese.

Results

Serum uric acid levels

As shown in Figure 1, the SU group exhibited the highest serum uric acid level at 129.7 µmol/L, which was significantly higher than that of the other two groups (P < 0.05). The serum uric acid level for the HPS group was measured at 56.6 µmol/L, which is notably lower than the CG group’s level of 70.8 µmol/L (P < 0.05).

Histological observation of ileum

Figure 2 illustrates the histological changes in the ileum across the treatment groups, highlighting key differences. CG group geese exhibit a disordered arrangement of ileal villi and indistinct contours of intestinal epithelial cells (Figure 2A). The ileal tissue structure in the HPS group is intact, with the villi organized orderly (Figure 2B). However, the SU group geese show damaged ileal villi, increased crypt depth, and shedding of intestinal villous epithelium (Figure 2C). At the same time, the villus height (VH) in the HPS group measured 1050.41 µm, which was significantly greater than that in both the CG and SU groups (P < 0.05) (Figure 2D). The crypt depth (CD) was 179.62 µm, significantly lower than that in the SU group (P < 0.05) (Figure 2E), and the ratio of villus height to crypt depth (VH/CD) was 5.32, significantly higher than that in the CG and SU groups (P < 0.05) (Figure 2F).

Goose ileum morphological results. (A–C) The results of hematoxylin-eosin Staining of the goose ileum in various treatment groups; scale bar: 200 μm. (D) Ileal villus. height (VH). (E) Ileal crypt depth (CD). (F) The ratio of villus height to crypt depth in the ileum (VH/CD). Bars labeled with the same letter indicate no significant difference (P > 0.05).

Overview of ileal transcriptome data

In this experiment, 12 different goose ileum transcriptome libraries were constructed. The average number of raw reads obtained from the experimental samples was 45,337,101. After removing low-quality reads and rRNA from the raw reads, an average of 44,882,192 clean reads was obtained from each sample. The Q30 value ranged from 91.64 to 93.98%, while the unique mapped values from the reference genome ranged from 86.31 to 90.44%, and the total mapped percentages varied from 88.13 to 92.23%. The data is presented in Table 1. Afterward, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed on the 12 samples. We observed that the ileum samples from the CG vs HPS, CG vs SU, and HPS vs SU groups were distributed in different sub-clusters, indicating the reliability of the screened DEGs, as shown in Figure 3.

Analysis of differentially expressed genes

For the reliability of the following experimental analysis, the CG, HPS group, and SU groups were compared in pairs, transcriptionally FPKM > 10 in at least one treatment group, |Fold change| ≥ 1.5 between compared groups, and statistical significance at P ≤ 0.05. As shown in Figures 4A–D, we identified 126 DEGs (Table S1) in the comparison of CG vs. HPS, which includes 66 up-regulated and 60 down-regulated genes. In the CG vs. SU comparison, 538 DEGs (Table S2) were identified, of which 380 were up-regulated and 158 were down-regulated. For the HPS vs. SU comparison, we identified 1337 DEGs (Table S3; among these, 784 were up-regulated and 553 were down-regulated. We conducted Venn analysis on the three groups of DEGs and found 11 genes in the intersection, as illustrated in Figure 4E.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) under various treatment groups. (A–C) DEGs volcanic maps of CG vs. HPS, CG vs. SU, and HPS vs. SU. The X-axis represents log2(Fold Change) and the Y-axis shows the -log10 (p-value). Red dots represent up-regulated genes, blue dots represent down-regulated genes and gray dots represent genes that were not differentially expressed. (D) Distribution map of the number of DEGs between the different groups. (E) Venn diagram of the DEGs.

GO functional enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes

We conducted a Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis on the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified in the ileum of geese across various treatment groups. The top 20 GO terms are presented in Fig 5 (P < 0.05). Among these, the DEGs from the CG vs HPS group showed significant enrichment for 548 GO terms, primarily in Biological Processes and Cellular Components. This includes terms such as Brush border membrane, Ribosomal subunit, Brush border, Protein targeting to membrane, and Cotranslational protein targeting to membrane (Figure 5A). The DEGs in the CG vs SU group were significantly enriched in 1575 GO terms, primarily related to immune functions such as Immune response, Immune system processes, Immune effector processes, Leukocyte activation, and Cell activation (Figure 5B). The DEGs in the HPS vs SU group were significantly enriched in 1758 GO terms, mainly including structural constituents of the Ribosome, Immune response, Cytoplasm, Cytosol, Cytoplasmic parts, and other related terms (Figure 5C).

GO enrichment analysis plot for differentially expressed genes (DEGs) across various treatment groups. (A) CG vs. HPS. (B) CG vs. SU. (C) HPS vs. SU. The bubble size represents the number of differential genes enriched in the GO term, and the color represents the enrichment significance in the GO term, and the larger the value, the more significant the enrichment.

KEGG enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes

Next, KEGG enrichment analysis was conducted on DEGs in the ileum of geese across different treatment groups, with the top 20 enriched pathways displayed in Fig 6 (P < 0.05). The significantly enriched pathway in the CG vs HPS group was the Ribosome (Figure 6A). The notably enriched pathways in the CG vs SU group were DNA replication, Pyrimidine metabolism, Cell cycle, and the Intestinal immune network for IgA production (Figure 6B). The significantly enriched pathways in the HPS vs SU group included the Ribosome, the Intestinal immune network for IgA production, the NF-kappa B signaling pathway, and the PPAR signaling pathway (Figure 6C).

KEGG enrichment analysis plot for differentially expressed genes (DEGs) across various treatment groups. (A) CG vs. HPS. (B) CG vs. SU. (C) HPS vs. SU. The bubble size represents the number of differential genes enriched in the pathway, and the color represents the enrichment significance in the pathway, and the larger the value, the more significant the enrichment.

Trend analysis

To reveal the ileum development across different treatment groups, we analyzed the expression trends of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with P < 0.05 as the screening criterion (HPS vs CG vs SU). The differential genes among the three groups were clustered into eight profiles. In Figure 7, the results indicated that three significant gene profiles (profiles 7, 0, and 4) were identified (P < 0.05), encompassing a total of 1171 genes. Of these, 776 genes were part of the up-regulated profiles (profiles 7 and 4), while 395 genes were included in the down-regulated profile. GO and KEGG functional enrichment analyses were conducted on the groups of up-regulated and down-regulated gene profiles, with the results depicted in Figure 8. GO functional annotation of up-regulated genes showed significant enrichment in Ribonucleoprotein complex, Immune response, Immune system process, and Intracellular organelle lumen (Figure 8A). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed pathways such as Ribosome, Intestinal immune network for IgA production, DNA replication, and NF-kappa B signaling pathway (Figure 8C). GO functional annotation of down-regulated profile genes was primarily enriched in GO terms related to membrane components such as Endosome, Brush border, Endomembrane system, Membrane, Integral component of membrane, and Membrane part (Figure 8B). Additionally, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis highlighted endocytosis and metabolic pathways (Figure 8D).

Trend analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Profile 7 (n = 490); Profile 0 (n = 395); Profile 4 (n = 286). The profile with similar trends has the same color, and the profiles with color have significant enrichment trends (P < 0.05). The profiles block without color is a non-significant enrichment trend, and each inflection point is a set of sample data.

Gene function enrichment analysis of up-profile and down-profile. (A) GO enrichment analysis of up-profile; (B) GO enrichment analysis of down-profile; (C) KEGG enrichment analysis of up-profile; (D) KEGG enrichment analysis of down-profile. The bubble size represents the number of differential genes enriched in the GO term (or pathway), and the color represents the enrichment significance in the GO term (or pathway), and the larger the value, the more significant the enrichment.

RT-qPCR validation

Six genes were randomly selected for RT-qPCR verification. The results, shown in Figure 9, indicate that the expression profiles of these DEGs measured by RT-qPCR were similar to the trends of the RNA-Seq sequencing results, highlighting the reliability of the transcriptome sequencing outcomes.

Discussions

The small intestine is the most important digestive organ and the largest immune organ. In this experiment, the SU group was administered 30 mg/d of sodium urate to observe the effect of ultra-high concentrations of uric acid on the intestinal health and uric acid metabolism of geese. In previous studies, some researchers have constructed hyperuricemia models through intraperitoneal injection or gavage of uric acid21,22. The high-risk period for gout in geese is from 0 to 30 days of age. Goose gout is a metabolic disease caused by several factors, including viruses and bacteria nutrition1,23. In this study, 30-day-old healthy geese were chosen as experimental subjects and a high-protein diet was used to induce uric acid metabolism disorders in the geese while excluding other interfering factors.

The results of ileal morphology indicated that VH increased (Figure 2B) and the VH/CD value also increased after feeding HPS (Figure 2F). Interestingly, after feeding SU, VH decreased, CD increased, the VH/CD ratio decreased, and intestinal villi were damaged (Figure 2F). Intestinal health is typically reflected by intestinal VH, CD, and their ratio24. Our results indicate that HPS can alleviate damage to the intestinal structure caused by high uric acid levels; however, excessively high concentrations of uric acid will still harm the ileum structure. Research suggests that a diet supplemented with raw potato starch (RPS, a resistant starch) can significantly enhance the villus height (VH) and villus height to crypt depth (VH/CD) ratios of duck cecum25. Furthermore, long-term consumption of RPS may improve intestinal morphology and promote epithelial protection in pigs’ colons26. In the experiment with rats fed hydroxypropylated corn starch, cecal mucin levels were found to be significantly higher than those in the starch control group27. Mucin is a vital component of the intestinal barrier and prevents potential pathogens from entering the underlying epithelium28. HPS generates SCFAs through intestinal microbial fermentation, which can lower intestinal pH and promote the growth of beneficial bacteria in the intestine27. SCFAs play an essential role in maintaining the normal state of the intestinal epithelium29. This may be one reason why HPS improves intestinal morphology.

To reveal critical genes and molecular mechanisms affecting goose intestinal health and uric acid transport, RNA-seq technology was utilized to analyze and compare changes in the transcriptome. The results of GO enrichment analysis indicated that the DEGs identified in the CG vs. HPS group ileum were significantly enriched in membrane components and ribosomes, such as the Brush border membrane, Ribosomal subunit, and Brush border, among others. The brush border is the microvilli-covered surface of the cuboidal and straight-tubed columnar epithelium found in the intestines, where microvilli aid absorption by increasing the surface area of the cells30. Transporters positioned at the top of the intestinal villi play a vital role in intestinal absorption and facilitate the transport of nutrients, including carbohydrates, proteins, fats, and SCFAs, within the small intestine31,32. Our results indicated that HPS up-regulated the expression of SLC1A1, SLC3A1, SLC5A1, SLC5A12, and SLC5A8 from the Solute Carrier Family. The proteins encoded by SLC1A1 and SLC3A1 act as the primary transporters for intestinal absorption of amino acids33. The protein encoded by SLC5A1 plays a crucial role in glucose transport34, SLC5A12 and SLC5A8 encode proteins that have the same substrate specificity and are responsible for transporting SCFA. Previous studies have demonstrated that SLC5A12 is expressed in the proximal region of the small intestine of mice and facilitates the transport of SCFAs derived from the diet, whereas SLC5A8 is responsible for transporting SCFAs produced through bacterial fermentation in the distal part of the small intestine35, and short-chain fatty acids can reduce serum uric acid in hyperuricemia mice36. In the present analysis, HPS up-regulated the expression of SLC5A12 and SLC5A8. It’s important to note that resistant starch primarily produces butyrate and propionate when acted upon by microorganisms37. They are the primary substrates for energy metabolism in intestinal cells, and butyrate has been shown to stimulate proliferation at the base of crypts, thus enhancing the renewal and maintenance of intestinal tissue villi38. The expression of intestinal SCFA transporters is induced by substrates in response to changes in intestinal SCFA concentration39. HPS may enhance the transport of nutrients by the intestinal epithelium by up-regulating the expression of the solute carrier family, thereby indirectly providing a material and energy basis for the growth of intestinal villi. In the SU group, the intestinal CD significantly increased, while the VH/CD significantly decreased. We speculate that the change in intestinal morphology leads to a decrease in nutrient absorption and uric acid excretion, resulting in the accumulation of serum uric acid. Additionally, KEGG enrichment analysis shows that DEGs are primarily enriched in ribosomes, which may help improve intestinal morphology through protein synthesis.

The GO enrichment results for the CG vs SU group indicated that differentially expressed genes (DGEs) were primarily enriched in Immune response, Immune system processes, Immune effect processes, Leukocyte activation, Cell activation, and other immune-related terms. It was found that anti-inflammatory-related genes NFKB1A, LGALS1, and PTPN640–42 were significantly up-regulated in the SU group, suggesting that the intestine was undergoing an inflammatory response. Previous studies have shown that the rise in uric acid in hyperuricemia mouse models is positively correlated with increased intestinal permeability, harmful intestinal bacteria, and damage to the intestinal barrier43,44. KEGG enrichment analysis indicated that DGEs were primarily enriched in DNA replication. PCNA plays a role in DNA replication45, and its significant up-regulation may indicate intestinal cells are in an active proliferation and differentiation state to resist antigens. The expression of RAC2 in the CG and SU groups was significantly higher than in the HPS group. The protein encoded by RAC2 can participate in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can directly kill microorganisms and play an important role in host defense46. It indicates that HPS can safeguard the intestinal barrier and enhance intestinal health by lowering uric acid levels. This aligns with the morphological findings of this experiment.

The results of GO enrichment analysis in the HPS vs SU group were mainly enriched in immune and cytoplasmic items, and the related DEGs were significantly enriched in the Intestinal immune network for IgA production, NF-kappa B signaling pathway, PPAR signaling pathway, and PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. This study found that the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα), and PDZ domain-containing 1 (PDZK1) was significantly up-regulated in the HPS group compared to the SU group. IgA is a crucial immunoglobulin in the intestine. As the first barrier, it limits the entry of antigens into the intestinal mucosa, controls the intestinal microflora, and inhibits pro-inflammatory immune response47. The pro-inflammatory function of the NF-kappa B signaling pathway has been confirmed in previous studies48. PPARγ can reduce inflammation by inhibiting NF-κB, which has a beneficial effect on inflammatory bowel disease49, and mice with PPARγ expression defects will develop into ileitis50. Studies indicate that PPARα activation is crucial in regulating intestinal cell regeneration, mucosal immunity, and intestinal health permeability51,52. This indicates that after uric acid damages the intestinal barrier, microbial invasion triggers an inflammatory response, activates the intestinal immune network, and may participate in the inflammatory response regulated by macrophages and endothelial cells through PPARγ PPARα53. In this study, the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway was activated in the HPS group, which preserves epithelial integrity during inflammation54. It was found that soluble uric acid increased the expression of PDZK1 and ABCG2 in intestinal cells by activating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway55, and ligand-activated PPARα induced expression of PDZK156. ABCG2 is the primary transporter involved in uric acid excretion in the intestine. It is highly expressed on the apical membrane of intestinal epithelial cells and facilitates the secretion of uric acid from these cells into the intestinal lumen57. The results indicated that HPS may lower inflammation and support intestinal health by up-regulating the expression of PPARγ. At the same time, HPS may regulate the expression of PDZK1 by up-regulating PPARα and activating the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, while also increasing the transport of uric acid in the intestine through the interaction between PDZK1 and ABCG255,58, thereby reducing serum uric acid levels.

Trend analysis was conducted to understand the expression pattern of DGEs. GO and KEGG functional enrichment analysis of up-regulated profiles genes revealed that DEGs were primarily enriched in immune-related processes, including Ribonucleoprotein complex, Immune response, Immune system processes, and the Intestinal immune network for IgA production. The GO and KEGG functional enrichment analysis of down-regulated profile genes demonstrated that DEGs were chiefly enriched in biofilm-related processes such as Endosome, Brush border Endomembrane system, and Metabolic pathways. It indicates that as uric acid concentration increases, the damage to the intestinal structure also worsens, leading to inflammation and stimulating intestinal immunity to produce IgA. Trend analysis indicated that HPS up-regulated the expression of Nuclear Receptor Subfamily 5 Group A Member 2 (NR5A2) and Inositol Polyphosphate Multikinase (IPMK). NR5A2 aids in restoring damaged intestinal epithelium by promoting the proliferation of stem cells and progenitor cells in the intestine crypts59. In a mouse model of chronic colitis induced by chemical dextran sulfate sodium (DSS), NR5A2 inhibition was shown to decrease the expression of intestinal steroidogenic genes, lower glucocorticoid synthesis, and sustain chronic inflammation60. IPMK can regulate various biological events, mediate the catalytic biosynthesis of inositol polyphosphate, and also regulate key signal transduction factors in a non-catalytic manner. Studies showed that IPMK preserved intestinal integrity by maintaining cluster cell homeostasis in DSS-induced mouse models61, and IPMK demonstrated enhanced intestinal epithelial repair function in irinotecan-induced mouse models62. Additionally, HPS also up-regulates the expression of ANKS4B and USH1C. The proteins encoded by ANKS4B and USH1C are abundant in brush border microvilli. ANKS4B plays a crucial role in brush border assembly during intestinal epithelial cell differentiation. When USH1C activates ANKS4B and MYO7B, a triplet complex is formed to anchor the microvilli tip to connect cadherin63,64. HPS may preserve the integrity of intestinal morphology and promote intestinal health by up-regulating the expression of NR5A2, IPMK, ANKS4B, and USH1C, which play a crucial role in intestinal nutrient absorption and uric acid metabolism.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that incorporating HPS positively influences intestinal morphology and uric acid metabolism. This indicates that HPS has considerable potential as a goose feed additive. In the future, gene editing technology may be used to enhance geese’s tolerance to uric acid, thereby reducing the incidence of gout and improving industrial benefits.

Materials and methods

Grouping and feeding of geese

In this experiment, 240 25-day-old Yangzhou geese with similar body weights were obtained from Bengbu Huaxin Poultry Co., Ltd., and the experiment commenced after 5 days of adaptive feeding. The 240 Yangzhou geese were randomly divided into three groups: Throughout the study, 5% corn starch was added to the control group (CG) diet, 5% hydroxypropyl starch was included in the hydroxypropyl starch group (HPS) and sodium urate group (SU) diets took 30 mg/d sodium urate on the last 4 days to simulate hyperuricemia. This experiment refers to the research methods of Li and Nagata on hydroxypropyl corn starch and insoluble fibre27,36. The experiment lasted for 21 d, with 4 replicates in each group and 20 geese in each replicate. During the experiment, all geese were free to eat and drink water and raised on a net bed. The feed formula is shown in Table 2.

Sample collection

Prior to sample collection, the experimental geese were fasted for 12 hours, during which they were allowed to drink water freely. The experimental geese were anesthetized using electric shock, and their blood was collected via the jugular vein method before they were humanely euthanized. The blood was stored at 4 °C for 3 hours to promote blood coagulation. centrifuged at 3000 r/min for 10 min to separate the serum and stored at − 20 °C. The terminal ileum was collected immediately after the goose was sacrificed and fixed in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution. Another terminal ileum was frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C until RNA isolation. Each replicate randomly slaughtered one goose, and four geese were killed in each group.

Determination of serum uric acid level

Serum uric acid content was determined by a uric acid detection kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China). Reaction systems were prepared according to the kit instructions. The reagent mixture, composed of Tris-HCl buffer, peroxidase, and uricase, was added to each reaction system at a volume of 250 µL. For the blank, standards, and measurement systems, 5 µL of distilled water, standard solution, and serum were added, respectively. After thoroughly mixing, the reaction mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. Following this, the absorbance of the blank, standards, and measurement systems was recorded at 510 nm and denoted as AB, AS, and AM. The uric acid calibrator (CC) concentration was 400 µmol/L, and the uric acid concentration for each sample was calculated using equation (1).

Histological observation of the ileum

The ileum was initially fixed in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution, which was replaced with a fresh solution after 24 h. Once the tissue was fully fixed, it underwent gradual dehydration using varying concentrations of alcohol, was cleared with xylene, and then embedded in paraffin. The embedded ileum was cut into 5 μm thick sections and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Biosharp). Finally, the stained sections were observed and photographed using a digital scanning microscope. Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software was employed to examine and analyze the ileum tissue sections of geese, measuring the intestinal villus height and crypt depth.

RNA extraction, library construction, and sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from the ileum of three groups of geese (n = 12) using a Trizol kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). After evaluating RNA integrity on an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA), the sequencing library was prepared using Illumina TruSeq mRNA (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions and was finally detected with Illumina Novaseq X Plus (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

Transcriptome alignment and assembly

Raw reads were filtered by fastp (version 0.18.0) and Bowtie2 (version 2.2.8)65,66. Paired-end clean reads were mapped to the reference genome using HISAT2 2.1.067. Then the mapped reads of each sample were assembled by using StringTie v1.3.168. Fragment per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) value was calculated, using RSEM software69. The Anser cygnoides reference genome was annotated and downloaded from the GenBank database (GCA_002166845.1).

Transcriptomic bioinformatics analysis

In order to reveal the relationship between samples, the R package model (http://www.r-project.org/) was used for principal component analysis (PCA). Differentially expressed genes were analyzed by DESeq70. The pairwise comparison of CG, HPS, and SU groups was performed. Considering transcriptionally FPKM >10 in at least one treatment group, |Fold change| ≥ 1.5 between compared groups, and statistical significance at P ≤ 0.0571. Subsequently, gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) functional enrichment analyses were performed using DESeq2 software. Trend analysis was performed using ShortTime-series Expression Miner software, with |Fold change| ≥ 1.5 as the screening condition, p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RT-qPCR analysis

To verify the accuracy of transcriptome sequencing, 6 DEGs were randomly selected for quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) verification. The reference gene was β-ACTIN, and the primers were designed by Primer Premier 5 (Table 3) and synthesized by Bioengineering (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. The reaction amplification system was 10 µL, which was mainly composed of 5 µL Taq SYBR ® Green qPCR Premix, 0.4 µL forward and reverse primers, 1 µL cDNA template, and 3.6 µL ddH2O. The RT-qPCR amplification procedure follows: pre-denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, denaturation at the same temperature for 10 s, annealing and extension at 60 °C for 30 s, cycle 45 times. Three biological replicate samples were collected from each sample, and the relative gene expression level was calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Statistical analysis

This study employed a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to assess the differences in uric acid concentration, VH, CD, and VH/CD among the various treatment groups. SPSS 26.0 software was utilized for statistical analysis, and Tukey’s HSD test was employed for post hoc comparison to determine whether the differences between treatment groups were significant. A p-value of < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. The results were visualized using Origin 2018 software.

Data availability

The original Yangzhou goose ileum sequencing data have been uploaded to the NCBI database, BioProject ID: PRJNA1174150.The BioProject and associated SRA metadata are available at https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1174150?reviewer=tser2s96tq8fl7vcl2huprjuv5 in read-only format.

References

Kumar, S., Kumar, S. & Kumar, A. Understanding the mechanism of gout in poultry and its management. Int. J. Vet. Sci. Anim. Husb. 8, 28–33 (2023).

El Ridi, R. & Tallima, H. Physiological functions and pathogenic potential of uric acid: A review. J. Adv. Res. 8, 487–493 (2017).

Hosomi, A., Nakanishi, T., Fujita, T. & Tamai, I. Extra-Renal elimination of uric acid via intestinal efflux transporter BCRP/ABCG2. PLOS ONE. 7, e30456 (2012).

Fathallah-Shaykh, S. A. & Cramer, M. T. Uric acid and the kidney. Pediatr. Nephrol. 29, 999–1008 (2014).

Yang, H. et al. Microbial community and short-chain fatty acid profile in gastrointestinal tract of goose. Poult. Sci. 97, 1420–1428 (2018).

Méndez-Salazar, E. O. & Martínez-Nava, G. A. Uric acid extrarenal excretion: The gut Microbiome as an evident yet understated factor in gout development. Rheumatol. Int. 42, 403–412 (2022).

Shao, T. et al. Combined signature of the fecal microbiome and metabolome in patients with gout. Front. Microbiol. 8 268, (2017).

Ma, W. et al. Persistent purine metabolic abnormality induces the aggravation of visceral inflammation and intestinal microbiota dysbiosis in Magang Goose. Front. Vet. Sci. 8, (2021).

Ristic, B., Sikder, M. O. F., Bhutia, Y. D. & Ganapathy, V. Pharmacologic inducers of the uric acid exporter ABCG2 as potential drugs for treatment of gouty arthritis. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 15, 173–180 (2020).

Nakayama, A. et al. Common missense variant of monocarboxylate transporter 9 (MCT9/SLC16A9) gene is associated with renal overload gout, but not with all gout susceptibility. Hum. Cell. 26, 133–136 (2013).

Caulfield, M. J. et al. SLC2A9 is a high-capacity urate transporter in humans. PLoS Med. 5, e197 (2008).

Nian, Y. L. & You, C. G. Susceptibility genes of hyperuricemia and gout. Hereditas 159, 30 (2022).

Bojarczuk, A., Skąpska, S., Mousavi Khaneghah, A. & Marszałek, K. Health benefits of resistant starch: A review of the literature. J. Funct. Foods. 93, 105094 (2022).

Yin, H., Liu, N. & Chen, J. The role of the intestine in the development of hyperuricemia. Front. Immunol. 13, (2022).

Vaziri, N. D. CKD impairs barrier function and alters microbial flora of the intestine: A major link to inflammation and uremic toxicity. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 21, 587 (2012).

Jiang, H., Feng, Y., Jane, J. & Yang, Y. Progress in understanding resistant-starch formation in hydroxypropyl starch: A minireview. Food Hydrocoll. 149, 109628 (2024).

Koguchi et al. Dietary fiber suppresses elevation of uric acid and Urea nitrogen concentrations in serum of rats with renal dysfunction induced by dietary adenine. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 74, 253–263 (2004).

Prasad, C., Iqbal, U., Westfall, S. & Prakash, S. Management of hyperuricemia and gout by prebiotics and probiotics: Potentials and limitations. Int. J. Probiotics Prebiotics 12 5 (2017).

Ebihara, K., Tachibe, M., Kaneko, N. & Kishida, T. Hydroxypropylation of high-amylose maize starch changes digestion and fermentation-dependent parameters in rats. J. Nutritional Sci. 3, e1 (2013).

Ebihara, K., Shiraishi, R. & Okuma, K. Hydroxypropyl-Modified potato starch increases fecal bile acid excretion in Rats1. J. Nutr. 128, 848–854 (1998).

Liu, X., Zhang, B. & Liu, C. Preliminary study on the establishment of quail hyperuricemia model. Chin. J. Pathophysiol 111–113 (2001).

Chen, G., Sun, X., Wang, Q., Zhang, X. & Liu, P. Research on mouse hyperuricemia model. Chin. Pharmacol. Bull. 350–352 (2001).

Zhou, Q. et al. Characterization of natural co-infection with Goose astrovirus genotypes I and II in gout affected goslings. Avian Pathol. 53 146 (2024).

Ducatelle, R. et al. Biomarkers for monitoring intestinal health in poultry: Present status and future perspectives. Vet. Res. 49, 43 (2018).

Qin, S. et al. Dietary administration of resistant starch improved caecal barrier function by enhancing intestinal morphology and modulating microbiota composition in meat Duck. Br. J. Nutr. 123, 172–181 (2020).

Nofrarias, M. Long-term intake of resistant starch improves colonic mucosal integrity and reduces gut apoptosis and blood immune cells. Nutrition 23, 861–870 (2007).

Nagata, R. et al. Chemical modification of cornstarch by hydroxypropylation enhances cecal fermentation-mediated lipid metabolism in rats. Starch - Stärke. 72, 1900050 (2020).

McGuckin, M. A., Lindén, S. K., Sutton, P. & Florin, T. H. Mucin dynamics and enteric pathogens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 265–278 (2011).

Martin-Gallausiaux, C., Marinelli, L., Blottière, H. M., Larraufie, P. & Lapaque, N. SCFA: Mechanisms and functional importance in the gut. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 80, 37–49 (2021).

Brush Border. in. Dictionary of Toxicology (edPant, A.) 154–154 (Springer Nature, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-9283-6_382

Yangzom D. Bhutia & Vadivel Ganapathy. Protein digestion and absorption. in Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract 1063–1086 (Academic Press, 2018) https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809954-4.00047-5

Kiela, P. R. & Ghishan, F. K. Physiology of intestinal absorption and secretion. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 30, 145–159 (2016).

Fairweather, S. J. et al. A GC-MS/single-cell method to evaluate membrane transporter substrate specificity and signaling. Front. Mol. Biosci. 8 646574, (2021).

Lehmann, A. & Hornby, P. J. Intestinal SGLT1 in metabolic health and disease. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 310 G887, (2016).

Srinivas, S. R. et al. Cloning and functional identification of slc5a12 as a sodium-coupled low-affinity transporter for monocarboxylates (SMCT2). Biochem. J. 392, 655–664 (2005).

Li, Y. et al. Insoluble fiber in barley leaf attenuates hyperuricemic nephropathy by modulating gut microbiota and Short-Chain fatty acids. Foods 11, 3482 (2022).

Deehan, E. C. et al. Precision Microbiome modulation with discrete dietary fiber structures directs Short-Chain fatty acid production. Cell. Host Microbe. 27, 389–404e6 (2020).

Brouns, F., Kettlitz, B. & Arrigoni, E. Resistant starch and the butyrate revolution. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 13, 251–261 (2002).

Sepponen, K., Ruusunen, M., Pakkanen, J. A. & Pösö, A. R. Expression of CD147 and monocarboxylate transporters MCT1, MCT2 and MCT4 in Porcine small intestine and colon. Vet. J. 174, 122–128 (2007).

Quan, J. et al. USP39 regulates NF-κB-Mediated inflammatory responses through deubiquitinating K48-Linked IκBα. J. Immunol. 210, 640–652 (2023).

de la Fuente, H. et al. The leukocyte activation receptor CD69 controls T cell differentiation through its interaction with galectin-1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 34, 2479–2487 (2014).

Poirier, A. et al. The induction of SHP-1 degradation by TAOK3 ensures the responsiveness of T cells to TCR stimulation. Sci. Signal. 17, eadg4422 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Protective effect of sodium butyrate on intestinal barrier damage and uric acid reduction in hyperuricemia mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 161, 114568 (2023).

Lv, Q. et al. Association of hyperuricemia with immune disorders and intestinal barrier dysfunction. Front. Physiol. 11 524236, (2020).

Baris, Y., Taylor, M. R. G., Aria, V. & Yeeles, J. T. P. Fast and efficient DNA replication with purified human proteins. Nature 606, 204–210 (2022).

Citalán-Madrid, A. F., García-Ponce, A., Vargas-Robles, H., Betanzos, A. & Schnoor, M. Small GTPases of the Ras superfamily regulate intestinal epithelial homeostasis and barrier function via common and unique mechanisms. Tissue Barriers. 1, e26938 (2013).

Pabst, O. New concepts in the generation and functions of IgA. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 12, 821–832 (2012).

Burkitt, M. D. et al. NF-κB1, NF-κB2 and c-Rel differentially regulate susceptibility to colitis-associated adenoma development in C57BL/6 mice. J. Pathol. 236, 326–336 (2015).

Wahli, W. A gut feeling of the PXR, PPAR and NF-κB connection. J. Intern. Med. 263, 613–619 (2008).

Sugawara, K. et al. Linkage to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma in SAMP1/YitFc mice and in human Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 128, 351–360 (2005).

Stojanović, O. et al. Dietary excess regulates absorption and surface of gut epithelium through intestinal PPARα. Nat. Commun. 12, 7031 (2021).

Grabacka, M., Płonka, P. M. & Pierzchalska, M. The PPARα regulation of the gut physiology in regard to interaction with microbiota, intestinal immunity, metabolism, and permeability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 14156 (2022).

Clark, R. B. The role of PPARs in inflammation and immunity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 71, 388–400 (2002).

Sun, Z. et al. Intestinal trefoil factor activates the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway to protect gastric mucosal epithelium from damage. Int. J. Oncol. 45, 1123–1132 (2014).

Chen, M. et al. Soluble uric acid increases PDZK1 and ABCG2 expression in human intestinal cell lines via the TLR4-NLRP3 inflammasome and PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Arthritis Res. Ther. 20, 1–12 (2018).

Tachibana, K. et al. Regulation of the human PDZK1 expression by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha. FEBS Lett. 582, 3884–3888 (2008).

Woodward, O. M. et al. Identification of a urate transporter, ABCG2, with a common functional polymorphism causing gout. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 106, 10338–10342 (2009).

Leask, M. P. & Merriman, T. R. The genetic basis of urate control and gout: Insights into molecular pathogenesis from follow-up study of genome-wide association study loci. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 35, 101721 (2021).

Kostadinova, F., Schwaderer, J., Sebeo, V. & Brunner, T. Why does the gut synthesize glucocorticoids? Ann. Med. 46, 490–497 (2014).

Huang, S., Li, C. & Zhong, B. Tumor necrosis factor suppresses NR5A2 activity and intestinal glucocorticoid synthesis to sustain chronic colitis. Sci. Signal. 7, ra20 (2014).

Park, S. E. et al. Gut epithelial inositol polyphosphate multikinase alleviates experimental colitis via governing tuft cell homeostasis. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14, 1235–1256 (2022).

Reilly, L. et al. Loss of PI3k activity of inositol polyphosphate multikinase impairs PDK1-mediated AKT activation, cell migration, and intestinal homeostasis. iScience 26, (2023).

Li, J., He, Y., Lu, Q. & Zhang, M. Mechanistic basis of organization of the Harmonin/USH1C-Mediated brush border microvilli Tip-Link complex. Dev. Cell. 36, 179–189 (2016).

Crawley, S. W., Weck, M. L., Grega-Larson, N. E., Shifrin, D. A. & Tyska, M. J. ANKS4B is essential for intermicrovillar adhesion complex formation. Dev. Cell. 36, 190–200 (2016).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 9, 357–359 (2012).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. Fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Kim, D., Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods. 12, 357–360 (2015).

Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 290–295 (2015).

Li, B. & Dewey, C. N. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 12, 323 (2011).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Gaines, T. A. et al. RNA-Seq transcriptome analysis to identify genes involved in metabolism-based Diclofop resistance in lolium rigidum. Plant J. 78, 865–876 (2014).

Funding

This research was supported by the Youth Project of the Provincial Natural Science Foundation of Anhui (2108085QC132), Anhui Provincial Key Research and Development Project (grant nos. 202204c06020003), Key Scientific Research Foundation of the Education Department of Province Anhui (grant nos. 2024AH050301) and Postdoctoral Research Project of Anhui Province (grant nos. 2024C865).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PY and WL developed the trial concept and participated in the study design. WL performed the main experiments and analyzed the data. XT performed bioinformatic analysis. ML, JH, XW, JZ, XH, XZ, QR, MC, and LZ participated in experimental animal management and tissue sampling. WL drafted this manuscript. PY reviewed this manuscript and revised it. PY acquired the funding and supervised this study. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Our study was carried out in compliance with the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines. All experimental procedures and sample collection were performed according to the Regulations for the Administration of Affairs Concerning Experimental Animals (Ministry of Science and Technology, China, revised in July 2013) and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the College of Animal Science and Technology, Anhui Science and Technology University, Chuzhou, China (permit No. AHSTU2023018).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, P., Liu, W., Tang, X. et al. Effects of hydroxypropyl starch on intestinal health and transcriptome of geese. Sci Rep 15, 12284 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96020-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96020-8