Abstract

In the past two decades, global cities have experienced a decline in urban population density, marked by urban land expansion outpacing population growth. The impact of this trend on urban population exposure to surface urban heat island (SUHI) has not been fully examined by considering the intra-city spatial variations in both population distribution and surface temperature. In this study, we examine the temporal trends of population-weighted SUHI extremes (as a proxy for spatial heat exposure) in the 1,000 largest global cities using high-resolution data from 2003 to 2020. Our findings reveal that cities with declining population densities experience a slower increase in population-weighted SUHI extremes compared to the rise in the area-average values, by approximately 0.5 ± 0.04 K per decade for every 1,000 persons/km2/year decrease in density (R2 = 0.71; P < 0.01). Conversely, cities undergoing densification face greater challenges in mitigating rising heat exposure. We further show that vegetation changes have a moderate association with changes in population-weighted heat exposure (R2 = 0.56), whereas variations in surface albedo exhibit a negligible relationship (R2 = 0.03). These results underscore the need for strategic urban planning to balance the benefits of densification with the imperative of reducing heat exposure risks. Urban greening efforts may offer some mitigation potential, while albedo-based interventions require further investigation to assess their effectiveness at scale. As cities worldwide pursue sustainability and economic growth through increasing density, it is critical to integrate heat exposure consideration into urban planning to enhance climate resilience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past few decades, most global cities have experienced a rapid expansion of urban land that has outpaced population growth, leading to a general decline in urban population density1,2,3. While the expansion of urban land has been linked to increased surface temperatures due to the urban heat island (UHI) effect4,5, the specific impact of declining population density on population exposure to surface heat extremes remains underexplored. Understanding these nuances is critical, as they can significantly influence how urban populations experience and respond to extreme heat conditions. By addressing these overlooked factors, our study aims to provide new insights into the relationship between the trends of urban density and heat exposure.

Within cities, population densities are generally highest in central areas, where elevated land prices promote compact development and efficient land use. From city centers to the periphery, population density typically declines due to lower land prices, which reduce the incentives for more efficient land use6,7. Although this pattern of decreasing density is common, the rate of decline varies significantly between cities, shaped by factors such as income levels, land use regulations, and transportation infrastructure8. In addition to population density, surface temperatures within cities also vary widely. Urban areas often experience higher temperatures than their rural surroundings, a phenomenon known as the urban heat island (UHI) effect9. This can be measured as the surface urban heat island (SUHI), using satellite-derived land surface temperature (LST) differences, or the canopy urban heat island (CUHI), based on near-surface air temperature differences. While CUHI is closely tied to human heat stress at the canopy level, SUHI reflects the thermal properties of urban surfaces, influencing energy consumption and serving as a proxy for heat exposure across built environments. This study focuses on SUHI due to the global availability of high-resolution LST data, enabling detailed analysis across 1,000 cities. This phenomenon, driven by distinct biophysical characteristics of urban environments—such as limited vegetation, darker surfaces, materials with high heat capacity, building geometry, and waste heat emissions—exacerbates health risks10 and energy use11. These factors differ across neighborhoods, leading to substantial temperature variations within cities12,13. Understanding these intra-city differences is crucial for assessing the population’s exposure to heat extremes.

Recent advances have highlighted that not only do urban forms and land use drive the UHI effect, but socio-ecological-economic factors and three-dimensional canopy structures also play a critical role in modulating thermal conditions. For example, studies by Yao et al.14 and Zhou et al.15 have demonstrated that integrating these factors yields a more nuanced understanding of heat health risk and thermal comfort. This insight motivates our focus on a population-weighted SUHI metric that explicitly links urban density with exposure to extreme heat.

Given the heterogeneous distribution of both population and surface temperatures within urban areas, it is crucial to consider intra-city variations when assessing the number of people exposed to different levels of heat. Traditional SUHI metrics typically measure area-averaged temperature increases, which do not account for how population distribution influences exposure to extreme heat. Studies that combined temperature data with population demographics have shown that neighborhoods with lower incomes and higher percentages of racial minorities often experience more intense urban heat island (UHI) effects16,17,18,19. However, these studies have predominantly focused on cities in the United States, with only one study examining 25 global cities18. This gap is significant because many Asian and African cities are experiencing unprecedented rates of urbanization under conditions that differ markedly from those in the United States. In these regions, rapid, often unplanned urban expansion, high population densities, and diverse climatic conditions can create unique urban forms that alter the dynamics of surface temperatures and population exposure to heat extremes. Given that over 80% of future urban population growth is expected to occur in Asia and Africa20, failing to capture these variations could lead to an underestimation of heat-related risks and limit the development of targeted, effective mitigation strategies. Furthermore, previous global-scale analyses of UHI patterns21,22,23 have often neglected the intra-city variations in population distribution, failing to capture the full extent of heat exposure in global urban contexts. Most regional and global studies have also not explored the temporal trends in UHI or population changes, leaving a critical gap in understanding the long-term patterns and drivers of population heat exposure in cities around the world. Addressing these gaps is essential for developing effective strategies to mitigate heat risks in rapidly urbanizing areas.

To address the knowledge gaps outlined above, our study integrates global, high-resolution, and long-term datasets on both population distribution24 and surface urban heat island (SUHI) effects5 to examine heat exposure trends in the 1,000 largest global cities, defined as functional urban areas (FUAs)25. FUAs represent the economic and functional boundaries of a city, encompassing both its densely populated urban centers and the surrounding commuting zones. Rather than focusing on annual or seasonal averages, we utilize the 99th percentile of SUHI during the warm season (June–August for the northern hemisphere and December-February for the southern hemisphere) to capture extreme heat conditions that pose the greatest risks to public health and strain energy infrastructure. We estimate the temporal trends of both area-average and population-weighted SUHI extremes for these cities from 2003 to 2020. To delineate the changes in urban areas over time, we use the impervious surface area within FUAs to mask urban land and population for a given year. The area-average SUHI extreme (\(SUHI_{A}\)) represents the land-based mean temperature, similar to metrics used in previous global-scale studies21,22,23, while the population-weighted SUHI extreme (\(SUHI_{P}\)) serves as a proxy for average population exposure to surface heat within a city. Building upon the existing body of literature that recognizes a general positive correlation between population density and UHI intensity26,27, we propose the population‑weighted SUHI metric designed to account for the important mediating role of urban form. Specifically, we compute SUHI at each urban pixel as the difference between the local temperature and a background (non-urban) temperature, and then weight this difference by the corresponding population count. In doing so, our metric does not merely reflect an overall rise in temperature with increased population density; it differentiates between scenarios in which the same density may lead to varied thermal outcomes due to differences in urban design and spatial configuration. For example, while densely populated neighborhoods with limited vegetation may exhibit significantly higher daytime surface temperatures26, high‑density vertical expansion combined with strategically placed open areas can help mitigate it through shadow effects and evapotranspiration28,29,30. By quantifying these spatial nuances, our population-weighted approach offers a more accurate representation of the population’s exposure to urban heat extremes, capturing both the influence of increasing density and the critical role of urban design in shaping thermal environments. In the absence of changes in urban forms, \(SUHI_{P}\) may increase even if \(SUHI_{A}\) remains unchanged, should residents move from cooler to hotter areas within a city. Conversely, \(SUHI_{P}\) can decrease if residents relocate from hotter to cooler areas. In scenarios of population growth, \(SUHI_{P}\) rises if new residents settle in hotter areas and falls if they move to cooler ones. However, because \(SUHI_{P}\) does not track the origins of these new residents, it cannot directly indicate changes in individual exposure to heat. To further understand the patterns and drivers of population-weighted SUHI in global cities, we perform regression analyses using the temporal trends of population-weighted density, vegetation, and surface albedo as independent variables.

Results

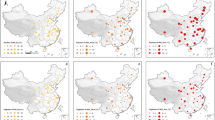

By incorporating intra-city variations in both population and temperature, our study aims to investigate whether the trends in the area-average warm-season 99th percentile surface urban heat island (\(SUHI_{A}\)) differ from those in the population-weighted surface heat extremes (\(SUHI_{P}\)). Figure 1a presents the global trends: over the past two decades, \(SUHI_{A}\) (blue line) has consistently increased across global cities, whereas \(SUHI_{P}\) (red line) initially rose but then declined, returning to its 2003 levels. These trend lines represent the population-weighted averages across all 1,000 cities, with more populous cities exerting a greater influence on the trends.

Trend in yearly warm season surface urban heat island (SUHI) maximum from 2003 to 2020. (a) the aggregate time series of average surface heat extremes (\(SUHI_{A}\), blue) and the population exposure them (weighted by population, \(SUHI_{P}\), red) in 1,000 global cities. The global values of \(SUHI_{A}\) and \(SUHI_{P}\) are aggregated as the weighted means of all cities, where the weights are their population sizes. (b) The distribution of population growth across cities with different trends of population-weighted surface urban heat island (\(\Delta SUHI_{P}\)), in different regions. In East Asia & Pacific, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa, the population has grown more in cities with positive trends; while in the rest of the world, population growth was evenly distributed among cities with both positive and negative trends. (c) The map of \(\Delta SUHI_{P}\) in global cities.

The initial rise in \(SUHI_{P}\) can be attributed to rapid urban expansion and population growth, particularly in areas with higher surface temperatures. As cities expanded, new populations often settled in areas with elevated temperatures, leading to increased population exposure to heat extremes. The subsequent decline and return to lower levels can be explained by a combination of factors. First, many cities experienced a decline in urban population density, primarily due to urban sprawl, where urban land expanded faster than population growth. This led to a more dispersed population, reducing the concentration of people in high-temperature areas. Second, urban planning interventions, such as increasing green spaces and improving building designs, helped mitigate heat exposure. Finally, natural population redistribution also played a role, with residents moving from high-density, high-temperature areas to lower-density, cooler areas.

Importantly, the trends in \(SUHI_{P}\) are not uniform across the globe. For example, cities in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and East Asia & Pacific experienced rapid increases in exposure, reaching up to 2.0 K per decade (Fig. 1c). During the same period, these regions also saw significant urban population growth, particularly in cities with positive \(SUHI_{P}\) trends (Fig. 1b). In East Asia & Pacific, population growth in cities with increasing \(SUHI_{P}\) (88 million) was more than double that of cities with decreasing \(SUHI_{P}\) (41 million; Supplementary Table 1). These findings indicate that while area-average and population-weighted SUHIs have generally followed different trends over the past two decades, the increase in population-weighted exposure has been significant in many, but not all, growing cities.

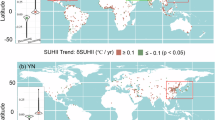

After highlighting the global-scale differences between the trends of area-average (\(\Delta SUHI_{A}\)) and population-weighted (\(\Delta SUHI_{P}\)) surface urban heat islands (Fig. 1a), we further explored these variations at the city level. Figure 2 shows a diverse range of \(\Delta SUHI_{A}\) and \(\Delta SUHI_{P}\) combinations across global cities. In Shanghai (China) and Lagos (Nigeria), for example, \(\Delta SUHI_{A}\) is positive while \(\Delta SUHI_{P}\) is negative, suggesting that although these cities experienced overall warming, they managed to reduce population exposure to extreme heat. In contrast, Lima (Peru) and Luanda (Angola) displayed negative \(\Delta SUHI_{A}\) but positive \(\Delta SUHI_{P}\), indicating that population exposure to heat increased despite overall urban cooling. Overall, 233 cities showed opposing trends in \(SUHI_{A}\) and \(SUHI_{P}\), collectively housing about 515 million people in 2020.

Trends of surface urban island maximum weighted by area (\(\Delta SUHI_{A}\) [K/decade], x-axis) and population (\(\Delta SUHI_{P}\) [K/decade], y-axis). The dashed line represents \(\Delta SUHI_{A} = \Delta SUHI_{P}\). The sizes of the bubbles are proportional to the population growth (million) from 2003 to 2020. Colors from green to purple represent the difference between the trends of the population- and area-weighted max surface heat island \(\Delta (SUHI_{P} - SUHI_{A} )\) [K/decade]. This difference between the two trends of SUHI shows the contribution from intra-city population distribution to the population exposure to surface temperature extremes.

Figure 2 provides a visual representation of the relationship between area-average and population-weighted SUHI trends. The dashed line represents the scenario where \(\Delta SUHI_{A}\) equals \(\Delta SUHI_{P}\) (i.e., the population-weighted trend matches the area-average trend). When a city falls above this line, it indicates that the population-weighted heat exposure (\(SUHI_{P}\)) increased more rapidly than the area-average heat exposure (\(SUHI_{A}\)). This suggests that the population is becoming more concentrated in areas with higher surface temperatures, potentially due to urban densification or migration into warmer neighborhoods. Conversely, when a city falls below this line, the population-weighted heat exposure (\(SUHI_{P}\)) increased more slowly than the area-average heat exposure (\(SUHI_{A}\)), indicating that the population is becoming more dispersed or relocating to cooler areas, which mitigates heat exposure despite overall urban warming.

For other cities, the differences between the two trends, \(\Delta (SUHI_{P} - SUHI_{A} )\) (illustrated by colors ranging from green to purple in Fig. 2), significantly altered the trajectories of population heat exposure. For instance, while the urban areas of Chongqing (China) and Addis Ababa (Ethiopia) warmed by more than 1 K per decade, their population-weighted heat exposures rose by less than 0.5 K per decade. Conversely, Tokyo (Japan) and Nairobi (Kenya) saw increases in \(SUHI_{P}\) exceeding 1 K per decade, despite their urban areas warming by less than 1 K per decade. The value of \(\Delta (SUHI_{P} - SUHI_{A} )\) reflects the impact of changing population distributions on the rise of population-weighted exposure to urban heat extremes. Notably, more than two-thirds of the studied cities (672 out of 1,000) exhibited negative \(\Delta (SUHI_{P} - SUHI_{A} )\) values, where approximately 70.3% (1.47 billion of 2.09 billion) of urban residents lived in 2020. These results indicate that the distribution of population within cities can attenuate the increase in population-weighted exposure to SUHI extremes.

Having demonstrated the significance of population distribution, we next analyzed which aspects of this distribution are linked to the differences between area-average and population-weighted exposures to SUHI extremes. We focused on changes in population-weighted average density (\(\Delta \rho_{N}\)), surface albedo (\(\Delta \alpha\)), and enhanced vegetation index (\(\Delta EVI\)) as explanatory variables (statistical descriptions in Supplementary Table 3 and multi-collinearity shown in Supplementary Table 4). Similar to \(SUHI_{P}\), the population-weighted calculations for density, albedo, and vegetation aim to capture the effects of intra-city population distribution on exposure to these factors. These indices increase if residents move from areas with lower values to areas with higher values of density, albedo, or vegetation; conversely, they decrease if relocations occur from high-value to low-value areas.

Table 1 presents the estimated coefficients and R2 values from linear regression models with different combinations of explanatory variables. In single-variable regressions (Models 1–3), changes in population density (\(\Delta \rho_{N}\)) demonstrated the strongest explanatory power (Model 1; R2 = 0.15). Changes in enhanced vegetation index (\(\Delta EVI\)) showed weaker explanatory power (R2 = 0.09), while changes in albedo (\(\Delta \alpha\)) were almost uncorrelated with \(\Delta (SUHI_{P} - SUHI_{A} )\) (R2 < 0.01). In multi-variable regressions (Models 4–6), the combination of \(\Delta \rho_{N}\) and \(\Delta EVI\) (Model 4) best explained the impact of population distribution on rising heat exposure (R2 = 0.20). Analyses using binned averages of these variables yielded similar results (Table 2), with strong associations for both \(\Delta \rho_{N}\) and \(\Delta EVI\), and the former showing greater explanatory power (R2 = 0.71 and 0.56, respectively). The estimated slopes of ΔρN were consistent and statistically significant across regressions using both all samples (\(5.05 \times 10^{ - 5}\)) and binned averages (\(5.29 \times 10^{ - 5}\)) (Fig. 3). Although the slopes for \(\Delta EVI\) differed between regressions with all samples (− 8.97) and binned averages (− 11.48), they were both negative (Supplementary Fig. 1). These consistent slope estimates suggest a pattern where declining density and increasing vegetation abundance can reduce the rise in population heat exposure. The negative correlation between \(\Delta EVI\) and \(\Delta \rho_{N}\) (Supplementary Table 4; r = − 0.2; p < 0.01) indicates that if a neighborhood has high population density, vegetation abundance is lower probably due to the constructions of more buildings, limiting the effectiveness of greening efforts in mitigating heat exposure. Therefore, despite the effectiveness of vegetation cooling of land, its cooling benefits for a population-weighted SUHI metric is smaller.

The relationship between the contribution from intra-city population distribution to extreme surface heat exposure, \(\Delta (SUHI_{P} - SUHI_{A} )\), and the changes in urban population density (\(\Delta \rho_{N}\)). Bubble colors from light to dark red represent the population densities (\(\rho_{N}\)), and bubble sizes represent city sizes (N) in 2020. The blue line is the linear regression of all cities using the least-square method. Blue diamonds and error bars show the binned averages and standard deviations of \(\Delta (SUHI_{P} - SUHI_{A} )\), where the number of bins is 30. Four black text boxes show the total numbers of cities (#cities) and their combined population (POP) within each quadrant.

Figure 3 illustrates the scatter plot of the relationship between urban area-average and population-weighted exposure changes, \(\Delta (SUHI_{P} - SUHI_{A} )\), and changes in population density (∆\(\rho_{N}\)). According to the regression coefficient (\(5.1 \times 10^{ - 5}\)), a decrease of 10,000 persons/km2/decade in a city’s average population density is associated with a slower rise in population-weighted heat exposure compared to area-average surface warming by 0.5 K per decade. A slower increase in population-weighted heat exposure (\(\Delta (SUHI_{P} - SUHI_{A} )\) < 0) was observed in 74.7% of cities (434 out of 581) with declining urban density (\(\Delta \rho_{N}\) < 0; Supplementary Table 2). In contrast, only about 56.8% of cities experiencing densification (\(\Delta \rho_{N}\) > 0) showed negative \(\Delta (SUHI_{P} - SUHI_{A} )\) values. The negative intercept (–0.17) indicates that, on average, population-weighted heat exposure rose more slowly than area-average SUHI by 0.17 K over the study period. This generally slower rise in \(SUHI_{P}\) compared to \(SUHI_{A}\) may be influenced by other factors, such as changes in population-weighted surface albedo and vegetation abundance. Our findings suggest that increasing urban population density complicates, but does not preclude, efforts to mitigate the rise in population-weighted exposure to surface urban heat extremes.

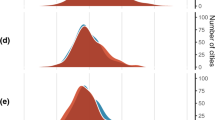

Using Shanghai, China, as an example, Fig. 4 demonstrates how a decline in urban density can lead to opposing trends in \(\Delta SUHI_{P}\) and \(\Delta SUHI_{A}\). During the study period (2003–2020), Shanghai’s population grew by 6 million, primarily in areas of medium (3000–30,000 persons/km2) and low (< 3000 persons/km2) density. The population in high-density areas (> 30,000 persons/km2) decreased from 4.7 million to 1.6 million, partly due to urban redevelopment projects that replaced dense, old housing in the city center with modern buildings featuring larger units31. Over the study period, the proportion of the population living in high-density areas fell from 33% to 8%, while those in medium- and low-density areas rose from 48% to 67% and 19% to 25%, respectively, leading to an overall decline in urban density. Given that SUHI extremes are higher in high-density areas (averaging 8.6–9.2 K) than in medium- (averaging 6.5–7.1 K) and low-density (averaging 3.6–3.7 K) areas, the redistribution of population from high- to medium- and low-density areas resulted in a decrease in population-weighted heat exposure (\(SUHI_{P}\)). Meanwhile, approximately 1,100 km2 of low-density area was converted to medium-density to accommodate population growth. Since medium-density areas are about 3 K warmer than low-density areas, the area-average SUHI extremes (\(SUHI_{A}\)) increased due to this land-use change. While changes in surface albedo and vegetation abundance can theoretically alter SUHI within each density category, in Shanghai, the changes in average SUHI extremes within each category were all below 0.6 K, consistent with our regression analyses showing that \(\Delta \alpha\) and \(\Delta EVI\) had less explanatory power than \(\Delta \rho_{N}\) over the study period. This example illustrates that intra-city population redistribution—quantified as \(\Delta (SUHI_{P} - SUHI_{A} )\)—can significantly affect population-weighted heat exposure, comparable to the impact of land-use changes, as measured by \(\Delta SUHI_{A}\).

The distributions of (a) population, (b) area, and (c) SUHI extremes in Shanghai (China) in 2003 and 2020. Different bars represent urban lands with three levels of population densities: high-density (> 30,000 persons/km2), medium-density (3000–30,000 persons/km2), and low-density (< 3000 persons/km2). In (a) and (b) the numbers by the bars show the percentages of population and land, respectively. In the boxplot of (c) black dots and numbers show the mean values of SUHI extremes.

Discussion

In this study, we examined trends in population-weighted urban surface heat extremes, measured as the 99th percentile of warm-season SUHI, across 1,000 global cities defined as functional urban areas. We found that in some cities, population-weighted SUHI extremes increased more rapidly than area-average measures, while in others, the opposite was true. Notably, cities in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and East Asia & Pacific, where population exposure to heat extremes grew rapidly, collectively housed 220 million people, compared to 108 million in cities where exposure grew more slowly. Our analysis of factors contributing to these differences revealed that changes in urban population density are significantly correlated with variations in heat exposure (R2 = 0.71; P < 0.01). Specifically, a decrease in a city’s average population density by 10,000 persons/km2 per decade was associated with a slower increase in population-weighted SUHI compared to area-average measures by approximately half a degree Kelvin per decade. Conversely, a similar rate of urban densification led to a faster rise in SUHI extremes by the same amount. These findings highlight the need to balance the benefits of urban densification with strategies to manage heat exposure.

As demonstrated in the Shanghai example, the observed association between declining population density and decreasing population exposure to heat may be resulted from the redistributions of residents from higher-density, hotter urban cores to lower-density suburban areas. These redistributions reflect complex technological, socioeconomic and demographic drivers32. Transportation technologies, ranging from railways and streetcars to automobiles and mopeds, have allowed residents to commute longer distances, making suburban living viable and attractive. Concurrently, rising incomes have supported suburban lifestyles, characterized by larger residences, private outdoor spaces, and perceptions of healthier living conditions. Employment decentralization, implicit government subsidies for suburban infrastructure and development, and persistent historical public health issues in dense urban cores have also encouraged population redistribution to the suburbs. Additionally, forced relocation due to urban redevelopment or slum clearance initiatives has involuntarily pushed populations to peripheral, often less desirable suburban or peri-urban areas. Recognizing these socio-economic and policy-driven factors is crucial for understanding the broader implications of declining urban densities on population exposure to urban heat extremes.

Despite the association between urban densification and the number of residents exposed to heat extremes shown here, high population density has been generally regarded as a desirable feature of the urban areas. Importantly, our findings do not support the conclusion that temperatures are rising in all cities in which population density is increasing over time. Instead, our study shows that higher population densities can lead to increased exposure to heat extremes, even if the overall SUHI intensity does not rise. This pattern often results from a redistribution of population from cooler to hotter areas within densifying cities. Therefore, urban heat mitigation strategies should focus on areas where an increasing number of residents are exposed to heat extremes, regardless of whether citywide SUHI intensity is rising. Our approach provides a method for identifying these high-vulnerability areas within cities. Additionally, our results showed weaker explanatory power for changes in vegetation (ΔEVI; R2 = 0.56) and albedo (Δα; R2 = 0.03), indicating that these heat mitigation measures have not been sufficiently prioritized in high-density areas during the study period.

However, it is essential to recognize the trade-offs associated with urban densification. While densification may increase heat exposure, it also offers significant benefits, such as reduced per capita energy use in transportation and building sectors. In terms of transportation, denser urban areas typically encourage shorter trips, improved public transportation, and greater use of active transportation modes such as walking and cycling33,34. Buildings in high-density areas also tend to be more energy-efficient in terms of heating and cooling per unit area due to smaller surface-to-volume ratios and shared walls35,36. Moreover, increased density can drive economic benefits such as higher productivity and wages; for instance, doubling population density can increase worker productivity by 2–4%, as observed in a U.S. study37. These gains are attributed to knowledge spill-overs among workers and reduced opportunity costs from shorter commutes38,39. While recognizing these benefits, our results underscore the need for targeted heat mitigation in densely populated areas, where the largest number of residents are affected by heat extremes. Based on our findings and existing literature, we propose two strategies to manage rising heat exposure in cities: mitigating urban heat and helping exposed populations adapt.

Urban heat mitigation strategies include measures such as expanding green spaces and increasing surface albedo to cool urban areas40,41. Previous large-scale studies using satellite imagery have demonstrated the importance of vegetation and albedo in determining SUHI intensities21,23. However, these studies typically analyzed area-average temperatures without accounting for population-weighted exposure, thereby overlooking the impact of stronger heat in more densely populated areas. Additionally, they often provided a snapshot of conditions without assessing whether changes in vegetation and albedo over time resulted in cooling. By addressing these limitations, our long-term, population-weighted analysis of SUHI underscores the effectiveness of enhancing vegetation (R2 = 0.56; P < 0.01, Table 2) but does not demonstrate a significant effect for changes in surface albedo (R2 = 0.03; P < 0.05). Although vegetation enhancement is important for mitigating heat exposure, it may not be the most effective strategy against rising heat exposure from urban densification. Our analysis of collinearity among explanatory variables found a negative correlation between vegetation enhancement (\(\Delta EVI\)) and densification (Supplementary Table 4; r = − 0.2; p < 0.01). As urban areas become more densely built to accommodate more people, the available space for green areas diminishes.

To address this trade-off between vegetation and density, one proposed solution is the "towers in the park" urban planning model pioneered by Le Corbusier42. However, this approach, featuring high-rise buildings surrounded by extensive green spaces, has been criticized for its potential negative social and sustainability outcomes. For instance, high-rise buildings with significant setbacks can reduce street-level social interactions, potentially leading to social isolation, as noted by urbanist Jane Jacobs43. Additionally, high-rise construction is often more carbon-intensive than low- or mid-rise buildings due to the need for more robust materials like steel and concrete35. Another potential solution is the installation of green roofs on low- or mid-rise buildings, although this approach also has challenges, such as high costs for construction and maintenance, as well as the risk of roof leakage44.

The other urban heat mitigation measure—increasing surface albedo—also warrants consideration, despite the null results in our analysis (R2 = 0.03; P < 0.05, Table 2). The lack of significant findings may be due to the minimal changes in population-weighted surface albedo observed in most sample cities from 2003 to 2020 (5th to 95th percentile range of \(\Delta \alpha\): [− 0.0088, 0.0080] per decade; Supplementary Table 3). In many urban areas, the changes in surface albedo may not be substantial enough to produce significant reductions in heat exposure. This is particularly true if the implementation of reflective materials is not widespread or if existing surfaces (like roads and rooftops) are not significantly modified to enhance their reflectivity. However, other large-scale studies using modeling techniques have suggested that increasing urban albedo could be more effective at surface cooling than green roofs11,41,45,46. The Global Cool Cities Alliance (GCCA), launched in 2010, promotes cost-effective measures such as installing highly reflective roofs and pavements to cool cities globally47. In our sample of the world’s 1000 largest functional urban areas, changes in population-weighted albedo over the past two decades have not been substantial enough to produce significant reductions in population heat exposure. The effectiveness of albedo as a heat mitigation strategy can vary greatly depending on the specific characteristics of the cities studied. Factors such as urban morphology, existing land cover, and the types of materials used in construction can all influence how effective albedo changes are in reducing urban heat. As more cities implement these measures promoted by the GCCA, further long-term observational studies are needed to evaluate their effectiveness.

Our population-weighted SUHI metric provides a unique lens to assess the effectiveness of heat mitigation strategies in the context of urban densification. If measures such as integrated green spaces, high-albedo surfaces, and optimized urban morphology were widely implemented, we would expect to see a weaker or even negative association between population density and population-weighted heat exposure. However, our analysis did not detect strong signals of such mitigation efforts on a global scale, suggesting that these strategies have not been systematically adopted in most cities. This finding underscores the gap between the theoretical benefits of urban heat mitigation and their real-world application. While some cities, particularly those with advanced urban planning initiatives, may have successfully integrated cooling strategies into high-density developments, the overall trend indicates that population growth in denser areas has not been accompanied by corresponding heat mitigation measures. Future research should examine case studies of cities that have effectively managed heat exposure despite increasing density, to identify best practices that can be scaled across different urban contexts.

Beyond reducing urban heat island intensity, enhancing adaptive capacity for exposed populations is also crucial for improving health outcomes related to heat exposure48. One effective adaptation strategy is ensuring access to air-conditioned spaces during extreme heat events. Although urban densification theoretically improves access to air conditioning (AC) by reducing cooling costs in high-density areas35,36, recent studies of 155 U.S. metropolitan areas indicate that AC is less prevalent in residential buildings in urban cores with higher population densities and more intense UHI effects49. Moreover, residents in these densely populated areas often have lower socioeconomic status, characterized by higher poverty rates, lower incomes, and less educational attainment. When home AC is unavailable, access to air-conditioned public spaces becomes vital, especially for lower-income residents who may not afford private vehicle ownership. Walking-based accessibility to such spaces benefits from higher urban density, as demonstrated in a study comparing Los Angeles County, CA, and Maricopa County, AZ50. In Los Angeles, an area with 50% higher density than Maricopa (870 vs. 580 parcels/km2), a significantly larger proportion of households (80% vs. 39%) had walkable access to public cooled spaces. To improve AC access in high-density areas, policies could include expanding energy assistance programs, subsidizing AC units and installation, creating public cooling centers, and incentivizing landlords to install energy-efficient AC in rental properties. Future research should explore the relationship between density and accessibility to cooled spaces in cities outside the U.S., as our findings indicate that the trade-offs between densification and heat exposure are prevalent globally.

One limitation of this study is the potential for inaccuracies in satellite measurements of land surface temperatures (LST) due to viewing angles (Du et al., 2023). When satellite viewing angles do not align with the direction of solar radiation, the sensors detect infrared emissions from both sunlit and shaded sides of buildings. Because sunlit surfaces generally have higher temperatures than shaded ones, this misalignment can lead to an underestimation of LST, especially in areas with taller buildings and higher population densities. This limitation might result in an underestimation of the actual heat exposure experienced by urban populations, particularly in high-density areas where the urban heat island (UHI) effect is typically stronger. As a result, our population-weighted SUHI estimates may be underestimated in dense urban environments where LST observations could be lower than the actual values. Future studies could explore the use of higher-resolution satellite data or alternative measurement methods to mitigate these limitations.

Another limitation is the reliance on LST as a proxy for heat stress impacts on urban populations. While LST is a useful indicator, physiological heat stress is also influenced by other factors, including air temperature, humidity, wind speed, and radiation51. Recent observational studies, such as those conducted in European cities52, suggest that LST may not always accurately represent the differences in heat stress between urban and rural areas. However, despite this limitation, many empirical studies have shown a positive correlation between LST and air temperature in urban contexts53,54,55 For instance, research in Madison, Wisconsin, found a significant relationship between land surface and air temperatures within the urban heat island53. Similarly, studies in cities like Portland, Oregon, and Washington, D.C., have shown that LST can effectively capture spatial variations in urban heat exposure54. Additionally, LST provides a practical and widely available metric for assessing heat risk at high spatial resolutions, which is crucial for identifying vulnerable areas within cities55. While other variables like humidity and wind speed are important, the lack of high-resolution data for these factors makes LST a more feasible choice for large-scale urban heat studies.

Moreover, the study does not fully account for the impacts of urban densification on other heat stress-related factors. For example, urban densification often leads to reduced humidity, as it is typically associated with the removal of vegetation and a decrease in evapotranspiration56. However, the effect of reduced humidity is less noticeable in humid climates, where the background heat stress is already elevated57. Additionally, urban densification can lower wind speeds because tall and bulky buildings obstruct airflow at the pedestrian level58. To mitigate these ventilation issues, maintaining low-density areas in strategically chosen “wind corridors” is crucial, particularly in high-density cities in wet climates59. These interactions between urban form and climate variables highlight the need for a comprehensive understanding of how densification affects heat stress, which future studies should address using detailed weather observations across urban areas with varying densities.

Finally, the 1-km spatial resolution of the LST data represents a limitation in detecting fine-scale temperature variations, particularly in dense urban cores where SUHI intensities can vary significantly over short distances, such as on a street-by-street scale. This averaging within each 1-km pixel may smooth out localized hotspots, potentially underestimating extreme heat exposure in areas with high spatial heterogeneity. Nevertheless, for this global analysis of trends in population-weighted SUHI extremes across 1,000 cities, the 1-km resolution is well-suited, providing a balance between spatial detail and the feasibility of consistent, large-scale analysis. Future studies could employ higher resolution data, such as 30 m Landsat imagery, to investigate the impact of street-level temperature variations on heat exposure in specific cities.

Despite these limitations, our study, to our knowledge, is the first to examine the global and long-term effects of urban densification on population exposure to extreme urban heat using LST as a measure. Our findings underscore the critical need to manage increasing heat exposure while balancing the economic and sustainability benefits associated with urban densification.

Methods

Intra-city surface temperature extremes

To measure the intra-city intensities of the surface urban heat island (SUHI) effect, we used the global high-resolution long-term mapping produced by Mentaschi et al.5. This dataset provides daily, 1-km resolution measurements of SUHI from 2003 to 2020 within the spatial boundaries of Functional Urban Areas (FUA) defined in the Global Human Settlement Layer (GHSL). The SUHI is measured as the difference in land surface temperature (LST) between an urban pixel (> 15% built-up) and the median LST of all non-built-up and non-water pixels within its 70 km radius.

We use the pixel-level 99th percentile of SUHI in the warm season of each year (June–August for the northern hemisphere and December-February for the southern hemisphere) to capture the localized surface temperature extremes. The 99th percentile was chosen as the metric for extreme heat conditions because it effectively captures the most extreme heat events, which pose the greatest risks to public health and strain energy infrastructure. This approach focuses on the upper tail of the temperature distribution, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the impacts of extreme heat in urban areas. Additionally, using the 99th percentile helps to account for the variability in heat exposure across different urban environments and ensures that the analysis is not skewed by less extreme temperature fluctuations. To calculate the area-average SUHI (hereafter referred to as \(SUHI_{A}\)), we compute the mean value of all impervious pixels within a city, defined by its FUA boundary.

We acknowledge that the 1-km spatial resolution of the global SUHI dataset, while valuable for ensuring consistent global coverage and comparability across diverse cities, may not capture localized temperature variations at the street or building scale. Therefore, our results are particularly suited to analyzing broad intra-city heat exposure trends but may underestimate fine-scale heat exposure differences relevant for detailed neighborhood-scale planning.

Urban population-weighted urban surface heat island (SUHI) extremes

Most previous large-scale studies21,22,23,60 of urban heat measure SUHI as the average LST within a city, similar to how we calculate \(SUHI_{A}\). However, since both SUHI and population vary spatially within a city, the area-average \(SUHI_{A}\) cannot accurately measure the population exposure to heat18,19. To account for the spatially heterogeneous heat exposure, we combine the pixel-level yearly warm-season SUHI extreme with the 1-km resolution annual population distribution data from Landscan24,61. To delineate the changes of urban lands over time within FUAs, we mask the SUHI extremes and population pixels using the annual maps of global artificial impervious areas (GAIA) data62. We use the equation below to calculate population heat exposure (\(SUHI_{P}\)) as the weighted average SUHI extreme within a city, where the weights are the number of people of each 1 by 1 km pixel.

where \(SUHI_{j}\) and \(POP_{j}\) are the \(SUHI_{1y}\) and population of the j-th pixel. This equation calculates the weighted average SUHI across all pixels within a city, with the weights being the population counts of each pixel. By incorporating population distribution, \(SUHI_{P}\) provides a more accurate representation of the population’s exposure to urban heat extremes compared to the area-average SUHI (\(SUHI_{A}\)), which does not account for population distribution.

Trends of area-average and population-weighted SUHI extremes

After defining the yearly warm season maximum area-average and population-exposure SUHI of each city, we evaluate the decadal rates of increases in \(SUHI_{A}\) and \(SUHI_{P}\) from 2003 to 2020 (K⁄decade) across different cities by fitting simple ordinary least squares (OLS) linear regression models. The rates of change in a city can be estimated using the equation below:

where \(SUHI_{Ai}\) and \(SUHI_{Pi}\) are the area-average and population-exposure SUHI for year i from 2003 to 2020. Here \(\beta\) and \(\varepsilon\) are the intercepts and errors, respectively. \(\Delta SUHI_{A}\) and \(\Delta SUHI_{P}\) are the decadal rates of changes, and the rates are multiplied by 0.1 to be converted to yearly rates.

Population-weighted explanatory variables: density, vegetation, and albedo

Similar to the calculation of population-exposure surface urban heat island extremes (\(SUHI_{P}\)), we measure the explanatory urban variables as the population-weighted average within an FUA. The explanatory urban variables include population density (\(\rho_{N}\)), enhanced vegetation index (EVI), and surface albedo (\(\alpha\)).

The population-weighted measures of these variables within each city are calculated by the equations below.

where \(\rho_{j}\), \(EVI_{j}\), and \(\alpha_{j}\) are respectively the population density, enhanced vegetation index, and surface albedo of the j-th pixel. Here, we use the population counts in each 1 by 1 km pixel of the LandScan population dataset56 to present population density, whose unit is persons/km2.

Similar to the trend analyses of SUHI, we estimate the decadal rates of increases of these three variables by fitting OLS linear regression models, using the equations below.

Data availability

The boundaries of cities defined as functional urban areas are available at: https://ghsl.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ghs_fua.php. All raster datasets used in this paper are available on Google Earth Engine (GEE; https://earthengine.google.com/). A GEE account is required to access these datasets on the platform. The global high-resolution, long-term maps of surface urban heat island (SUHI) can be assessed by: ee.ImageCollection(“users/lorenzomentaschi/uhiModis”) and ee.ImageCollection(“users/lucfeyen3/uhiModis”). Access to these SUHI datasets is granted by Lorenzo Mentaschi (lorenzo.mentaschi@unibo.it). The Landscan population grids is available as: ee.ImageCollection("projects/sat-io/open-datasets/ORNL/LANDSCAN_GLOBAL"). The surface albedo is available as ee.ImageCollection("MODIS/061/MCD43A3"). The enhanced vegetation index (EVI) is available as ee.ImageCollection("MODIS/061/MOD13A2").

Code availability

The code used to calculate population-weighted surface heat island extremes is available at: https://github.com/kangning-huang/PopWeightedUHI.

References

Güneralp, B., Reba, M., Hales, B. U., Wentz, E. A. & Seto, K. C. Trends in urban land expansion, density, and land transitions from 1970 to 2010: a global synthesis. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 044015 (2020).

Angel, S., Lamson-Hall, P., Blei, A., Shingade, S. & Kumar, S. Densify and expand: A global analysis of recent urban growth. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 13, 3835 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. High-spatiotemporal-resolution mapping of global urban change from 1985 to 2015. Nature (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. Surface warming in global cities is substantially more rapid than in rural background areas. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 1–9 (2022).

Mentaschi, L. et al. Global long-term mapping of surface temperature shows intensified intra-city urban heat island extremes. Glob. Environ. Change 72, 102441 (2022).

Fujita, M. Urban Economic Theory. Cambridge Books (1989).

Zheng, M., Huang, W., Xu, G., Li, X. & Jiao, L. Spatial gradients of urban land density and nighttime light intensity in 30 global megacities. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 10, 1–11 (2023).

Bertaud, A. Order without design: How markets shape cities. Town Region. Planning 79, 2–5 (2021).

Oke, T. R. The energetic basis of the urban heat island. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc. 108, 1–24 (1982).

Heaviside, C., Macintyre, H. & Vardoulakis, S. The urban heat island: Implications for health in a changing environment. Curr. Environ. Health Rpt 4, 296–305 (2017).

Akbari, H. Cooling our communities. A Guidebook on Tree Planting and Light-colored surfacing - eScholarship. https://doi.org/10.2172/10155334 (2009).

Yuan, F. & Bauer, M. E. Comparison of impervious surface area and normalized difference vegetation index as indicators of surface urban heat island effects in Landsat imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 106, 375–386 (2007).

Chakraborty, T. & Lee, X. A simplified urban-extent algorithm to characterize surface urban heat islands on a global scale and examine vegetation control on their spatiotemporal variability. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 74, 269–280 (2019).

Yao, X. et al. A novel integrated socio-ecological-economic index for assessing heat health risk. Ecol. Indic. 169, 112840 (2024).

Zhou, S.-Q. et al. Vertical canopy structure dominates cooling and thermal comfort of urban pocket parks during hot summer days. Landsc. Urban Plan. 254, 105242 (2025).

Voelkel, J., Hellman, D., Sakuma, R. & Shandas, V. Assessing vulnerability to urban heat: A study of disproportionate heat exposure and access to refuge by Socio-demographic status in Portland, Oregon. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15, 640 (2018).

Huang, G., Zhou, W. & Cadenasso, M. L. Is everyone hot in the city? Spatial pattern of land surface temperatures, land cover and neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics in Baltimore. MD. J. Environ. Manag. 92, 1753–1759 (2011).

Chakraborty, T., Hsu, A., Manya, D. & Sheriff, G. Disproportionately higher exposure to urban heat in lower-income neighborhoods: a multi-city perspective. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 105003 (2019).

Hsu, A., Sheriff, G., Chakraborty, T. & Manya, D. Disproportionate exposure to urban heat island intensity across major US cities. Nat. Commun. 12, 2721 (2021).

United Nations Publications. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision. (UN, 2019).

Clinton, N. & Gong, P. MODIS detected surface urban heat islands and sinks: Global locations and controls. Remote Sens. Environ. 134, 294–304 (2013).

Manoli, G. et al. Magnitude of urban heat islands largely explained by climate and population. Nature 573, 55–60 (2019).

Peng, S. et al. Surface urban heat island across 419 global big cities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 696–703 (2012).

Rose, A. N. & Bright, E. The LandScan Global Population Distribution Project: current state of the art and prospective innovation. Oak Ridge National Laboratory (2014).

Dijkstra, L., Poelman, H. & Veneri, P. The EU-OECD definition of a functional urban area. (2019).

Ramírez-Aguilar, E. A. & Lucas Souza, L. C. Urban form and population density: Influences on Urban Heat Island intensities in Bogotá. Colombia. Urban Clim. 29, 100497 (2019).

Tang, J., Di, L., Xiao, J., Lu, D. & Zhou, Y. Impacts of land use and socioeconomic patterns on urban heat Island. Int. J. Remote Sens. 38, 3445–3465 (2017).

Giridharan, R., Ganesan, S. & Lau, S. S. Y. Daytime urban heat island effect in high-rise and high-density residential developments in Hong Kong. Energy Build. 36, 525–534 (2004).

Yan, J. et al. The influence of urban form on land surface temperature: A comprehensive investigation from 2D urban land use and 3D buildings. Land (Basel) 12, 1802 (2023).

Roth, M., Sanchez, B., Li, R. & Velasco, E. Spatial and temporal characteristics of near-surface air temperature across local climate zones in a tropical city. Int. J. Climatol. 42, 9730–9752 (2022).

Shi, J., Min, X., Si, H., Tang, D. & Miao, W. The transition from housing demolition to conservation and renovation in Shanghai: Challenges and countermeasures. Land 8, 175 (2019).

Harris, R. Suburbanization and Suburbanism. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences 660–666 (Elsevier, 2015).

Saelens, B. E., Sallis, J. F. & Frank, L. D. Environmental correlates of walking and cycling: Findings from the transportation, urban design, and planning literatures. Ann. Behav. Med. 25, 80–91 (2003).

Kennedy, C. et al. Greenhouse gas emissions from global cities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 7297–7302 (2009).

Rickwood, P., Glazebrook, G. & Searle, G. Urban structure and energy—a review. Urban Policy Res. 26, 57–81 (2008).

Rickwood, P. Residential operational energy use. Urban Policy Res. 27, 137–155 (2009).

Abel, J. R., Dey, I. & Gabe, T. M. Productivity and the density of human capital. J. Reg. Sci. 52, 562–586 (2012).

Glaeser, E. L. & Resseger, M. G. The complementarity between cities and skills. J. Reg. Sci. 50, 221–244 (2010).

Xiao, H., Wu, A. & Kim, J. Commuting and innovation: Are closer inventors more productive?. J. Urban Econ. 121, 103300 (2021).

Mackey, C. W., Lee, X. & Smith, R. B. Remotely sensing the cooling effects of city scale efforts to reduce urban heat island. Build. Environ. 49, 348–358 (2012).

Zhao, L., Lee, X. & Schultz, N. A wedge strategy for mitigation of urban warming in future climate scenarios. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 1–28 (2017).

Corbusier, L. Towards a New Architecture. (Courier Corporation, 2013).

Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961).

Shafique, M., Kim, R. & Rafiq, M. Green roof benefits, opportunities and challenges—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 90, 757–773 (2018).

Georgescu, M., Morefield, P. E., Bierwagen, B. G. & Weaver, C. P. Urban adaptation can roll back warming of emerging megapolitan regions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, 2909–2914 (2014).

Krayenhoff, E. S., Moustaoui, M., Broadbent, A. M., Gupta, V. & Georgescu, M. Diurnal interaction between urban expansion, climate change and adaptation in US cities. Nat. Clim. Chang. 8, 1097–1103 (2018).

Global Cool Cities Alliance. Global Cool Cities Alliance https://globalcoolcities.org/ (2014).

Wilhelmi, O. V. & Hayden, M. H. Connecting people and place: A new framework for reducing urban vulnerability to extremeheat. Environ. Res. Lett. 5, 014021 (2010).

Romitti, Y., Sue Wing, I., Spangler, K. R. & Wellenius, G. A. Inequality in the availability of residential air conditioning across 115 US metropolitan areas. PNAS Nexus 1, gac210 (2022).

Fraser, A. M. et al. Household accessibility to heat refuges: Residential air conditioning, public cooled space, and walkability. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 44, 1036–1055 (2017).

Oleson, K. W. et al. Interactions between urbanization, heat stress, and climate change. Clim. Change 129, 525–541 (2015).

Chakraborty, T., Venter, Z. S., Qian, Y. & Lee, X. Lower urban humidity moderates outdoor heat stress. AGU Adv. 3, (2022).

Berg, E. & Kucharik, C. The dynamic relationship between air and land surface temperature within the Madison, Wisconsin urban heat island. Remote Sens. (Basel) 14, 165 (2021).

Shandas, V., Makido, Y. & Upraity, A. N. Evaluating differences between ground-based and satellite-derived measurements of urban heat: The role of land cover classes in Portland, Oregon and Washington, D.c. Land (Basel) 12, 562 (2023).

Cao, J., Zhou, W., Zheng, Z., Ren, T. & Wang, W. Within-city spatial and temporal heterogeneity of air temperature and its relationship with land surface temperature. Landsc. Urban Plan. 206, 103979 (2021).

Lebakula, V. et al. LandScan Global 30 Arcsecond Annual Global Gridded Population Datasets from 2000 to 2022. Sci Data 12, 495 (2025).

Zhang, K. et al. Increased heat risk in wet climate induced by urban humid heat. Nature 617, 738–742 (2023).

Ng, E. Policies and technical guidelines for urban planning of high-density cities—air ventilation assessment (AVA) of Hong Kong. Build. Environ. 44, 1478–1488 (2009).

Ng, E., Yuan, C., Chen, L., Ren, C. & Fung, J. C. H. Improving the wind environment in high-density cities by understanding urban morphology and surface roughness: A study in Hong Kong. Landsc. Urban Plan. 101, 59–74 (2011).

Zhou, B., Rybski, D. & Kropp, J. P. On the statistics of urban heat island intensity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 5486–5491 (2013).

Bhaduri, B., Bright, E., Coleman, P. & Urban, M. L. LandScan USA: A high-resolution geospatial and temporal modeling approach for population distribution and dynamics. GeoJournal 69, 103–117 (2007).

Gong, P. et al. Annual maps of global artificial impervious area (GAIA) between 1985 and 2018. Remote Sens. Environ. 236, 111510 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the reviewers for their insightful comments and constructive feedback, which have significantly enhanced the quality of our manuscript. This work is sponsored by the Shanghai Pujiang Program (23PJ1410100 STCSM).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.H. conceptualized the study. K.H. conducted the study. K.H., B.S., C.G., and J.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, K., Stone, B., Guan, C. et al. Declining urban density attenuates rising population exposure to surface heat extremes. Sci Rep 15, 13860 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96045-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96045-z

This article is cited by

-

Trends in bioclimatic design strategies for climate change–induced heat stress mitigation based on a literature review

International Journal of Biometeorology (2025)