Abstract

Sub-10 nm nanostructures with high precision and uniformity are of significant interest due to their unique quantum properties and critical role in next-generation devices. However, current fabrication techniques are often constrained by the slow, small-area processes of electron beam lithography or the high costs of extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography, limiting broader accessibility. To address these challenges, we have advanced the atomic layer lithography method into an efficient, scalable approach for fabricating sub-10 nm nanogaps with high uniformity across entire wafer areas. The key strategy of this method is the direct employment of photoresist patterns as both protective and sacrificial layers, streamlining the process. Comprehensive optical and electron microscopy analyses, supported by COMSOL simulations and terahertz transmission measurements, confirm the formation of highly uniform, high-quality nanogaps across the entire wafer. Compared to the original atomic layer lithography, our approach offers enhanced patterning flexibility, including a simplified process, improved compatibility with a wide range of metals, and the ability to perform additional patterning on initial nanogap structures. This scalable technique, compatible with standard lithographic tools, provides a promising pathway for sub-10 nm nanogap fabrication, with strong potential for both academic research and industrial applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sub-10 nm nanostructures have emerged as transformative elements in nanoscale engineering, offering unparalleled advantages in nanophotonics and high-density integrated electronics1,2. Among nanoscale architectures, nanogaps are unique due to their ability to localize and amplify electromagnetic (EM) fields within volumes significantly smaller than the wavelength of light2. This extreme confinement results in ‘hotspots’ that facilitate quantum mechanical effects and significantly enhance light-matter interactions3,4,5. Nanogap-based devices are pivotal in advancing research and applications across multiple scientific disciplines6,7. For instance, their role in terahertz (THz) technology includes enhancing field confinement and facilitating precise modulation of long-wavelength EM waves8,9,10. Nanogap also underpins innovations in molecular detection and single-molecule spectroscopy by leveraging amplified EM fields11,12,13. In the realm of energy technologies, they serve as rectenna components, converting electromagnetic waves into direct current with improved efficiency14.

To fabricate sub-10 nm nanogap structures, electron beam lithography (EBL) and ion beam lithography are commonly employed due to their high resolution and precision15,16,17. However, both methods face substantial challenges in terms of scalability and production yield. These techniques are constrained by their small working areas and slow processing speeds, rendering them impractical for fabricating even millimeter-scale devices. As a result, there is a growing demand for fabrication methods capable of producing sub-10 nm structures across entire wafers, enabling the mass production of nanodevices. In response to this need, advanced fabrication techniques, such as nanoimprint lithography (NIL) and extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography, have been introduced18,19,20,21. Although they offer scalability and cost-efficiency, NIL faces issues with defect rates and mold wear during imprinting, while EUV lithography is hindered by the substantial costs of equipment and operational complexity, limiting its accessibility for broader applications. Also, adhesion lithography (a-Lith) is another noteworthy technique that utilizes self-assembled monolayers for nanogap fabrication with relatively low cost and compatibility with various materials22,23. This method is highlighted for its simplicity and scalability. However, achieving uniformity across large areas remains challenging due to the need for precise control over substrate adhesion and peeling processes. A comparative summary of these methodologies for wafer-scale sub-10 nm nanostructure fabrication is provided in Supplementary S1.

As an alternative to the aforementioned techniques, the atomic layer lithography (ALL) method was first demonstrated by Chen. X and Park. H. -R. and colleagues in 2013, utilizing standard photolithography in combination with atomic layer deposition (ALD)24. A key feature of ALD in this context is its flexibility in adjusting deposition cycles, allowing precise control over the thickness of dielectric layers for nanometer-scale structures. Furthermore, the ALL method, when paired with conventional UV lithography, offers a cost-effective means of producing nanostructures with desired patterns, making it an accessible approach for researchers across diverse fields. However, the initial implementation of the ALL method faced several limitations due to the mechanical exfoliation in the final step. First, while UV lithography enables large-scale patterning, the overall pattern scale achievable with this approach was inherently restricted by the manual nature of mechanical peeling-off, leading to a very low yield of nanogap fabrication. Second, uneven surfaces on the resulting nanostructures often compromised device performance.

Since its beginning, numerous efforts have been made to address these challenges and enhance the ALL method, as summarized in Table S2. Among these, a particularly notable advancement was introduced by Jeong et al. in 2015, who replaced the mechanical peeling-off process with a chemical etching technique25. This approach significantly improved nanogap yield by eliminating the reliance on adhesive tape. Moreover, this modification facilitated the production of diverse nanostructure geometries. Despite these advancements, the ALL method remains constrained by the limitations of chemical etching, particularly when applied to a broader array of metal species, including silver (Ag), copper (Cu), aluminum (Al), and titanium (Ti), and so on26.

In this study, we decisively strengthened the ALL method by employing a photoresist layer as both a protective mask and a sacrificial layer in the fabrication process, to fabricate a sub-10 nm slot antenna array across the entire wafer. The formation of sub-10 nm nanogap was rigorously verified via optical and electron microscopy, complemented by terahertz time-domain spectroscopy (THz-TDS). Notably, THz-TDS measurements were performed across the entire wafer, revealing uniform spectral characteristics that confirmed the consistent fabrication of sub-10 nm slot antenna arrays on a wafer scale. This uniformity underscores the method’s reliability for large-area applications. Furthermore, this study demonstrated the successful fabrication of 10 cm-long slits and introduced the use of previously challenging metal combinations, such as Cu and Ag, alongside adhesion layers. These advancements effectively addressed the limitations of earlier ALL methods, including constraints on pattern shape and material compatibility issues. Leveraging these improvements, the enhanced ALL method provides a robust foundation for additional post-processing, enabling the development of complex and diverse applications in fields ranging from optics to electronics and advanced sensing technologies. This work presents a groundbreaking approach to sub-10 nm nanostructure fabrication, offering a cost-efficient, scalable production method with high yields, poised to significantly advance both academic research and industrial applications.

Methods

Fabrication of sub-10 nm slot antenna array across the entire wafer by advanced atomic layer lithography

As illustrated in Fig. 1a, the fabrication process began with the deposition of a 50 nm-thick Ag film with a 3 nm-thick chromium (Cr) as an adhesion layer on a substrate. Standard photolithography with a photomask (Fig. S1a) was then applied to define a photoresist pattern on the Ag film across the entire wafer. The exposed regions of the Ag layer were subsequently removed via argon (Ar) ion beam milling, with the photoresist pattern serving as a protective mask for the underlying Ag layer. A conformal aluminum oxide (Al2O3) dielectric layer was deposited using ALD over 33 cycles, followed by the deposition of a secondary Ag layer with a Cr adhesion layer via electron-beam evaporation under identical conditions. Next, the sample underwent a second Ar ion beam milling step at an 80° angle for 150 s, followed by treatment with a 1 M potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution to expose the sidewalls of the photoresist pattern in preparation for subsequent processing. Finally, the photoresist pattern, along with the excess Al2O3 and secondary Ag layers above the first Ag film, was removed via a lift-off process using N-Methyl-2-Pyrrolidone (NMP). Notably, due to the hardening of the photoresist during the high temperature ALD and Ar ion beam milling steps, the lift-off process necessitated a highly effective organic solvent to ensure complete removal without residue. The final structure was then achieved by rinsing the sample thoroughly with isopropyl alcohol (IPA). Further details of the fabrication process are provided in Supplementary 1, S3.

Wafer-scale fabrication of sub-10 nm nanogap slot antenna array via the advanced atomic layer lithography (ALL). (a) Schematics of the fabrication process, showing the use of a photoresist pattern as both a protective mask and a sacrificial layer—an improvement over conventional ALL methods. (b) Photograph of the wafer following the completion of the fabrication process. (c) Optical microscopy image of the sample, showing a slot antenna array with dimensions of 20 μm × 80 μm. Due to the low contrast in observations, the image has been adjusted to enhance the visibility of the array. (The 3D schematic images were generated using Web Vpython 3.2 in GlowScript, https://www.glowscript.org).

THz-TDS measurements

In the THz-TDS experimental setup shown in Fig. S3a, a mode-locked femtosecond Ti: Sapphire laser, with a center wavelength of 800 nm, an 80 MHz repetition rate, and a pulse duration of 130 fs, was used for both the pump and probe beams to generate and detect THz waves, respectively27. The pump beam was directed onto a low temperature-grown gallium arsenide (LT-GaAs) photoconductive antenna (PCA) to excite charge carriers within the GaAs, which were then rapidly accelerated by an applied bias on the PCA, generating THz pulses. The emitted THz pulses were collected and collimated using a series of parabolic mirrors, minimizing optical aberrations and focusing the THz waves onto the sample at normal incidence for precise transmission measurements. After interaction with the sample, the transmitted THz pulses were recollimated by another set of parabolic mirrors and directed toward the detection system. For detection, electro-optic (EO) sampling was performed using a (110)-oriented ZnTe crystal. When the transmitted THz pulses induced birefringence in the ZnTe crystal, the polarization of the incident probe beam was modulated. The modulated beam was directed through a quarter-wave plate (QWP) and a Wollaston prism to a balanced detector, which captured the modulation and recorded the temporal profile of the THz electric field. Time-domain traces of the THz pulses were obtained by systematically moving the pump delay stage, enabling precise measurement of the THz waveforms. The THz spectrum in the frequency domain was then extracted by applying a fast Fourier transform (FFT) to the time-domain traces.

COMSOL simulations

To investigate the optical properties of the slot antenna array, we employed finite element method (FEM) simulations using COMSOL software. First, the overall structure in the simulations consisted of a silicon (Si) substrate with a metallic film, where the metallic layer was perforated and filled with a ring-shaped Al2O3 spacer. The Al2O3 spacer, with a sub-10 nm width, formed between the two metallic layers. We calculated cases with slot widths ranging from 3 to 8 nm. The patterns were defined as 20 μm × 80 μm rectangular slots within a unit cell of 40 μm × 100 μm. This resulted in optical simulation outcomes for six distinct cases. For further accurate simulation results, precise optical constants of each material are essential. Therefore, we referenced previously reported refractive indices and dielectric constants for the calculations28. Notably, the metallic film exhibits dispersive characteristics in the THz region. Hence, we employed the Drude model to define the dielectric constant of the Ag film29. The dielectric constant of the metallic film can be defined as follows:

where \(\:{\omega\:}_{p}\) is the plasma frequency, and \(\:\gamma\:\) is the damping frequency. At the THz frequency, \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{\infty\:}\)exhibits relatively small values, so it can be approximated as 128. The material parameters used for the FEM simulations are provided in the Table 1.

Results and discussion

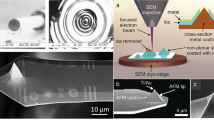

Figure 1b and c show an overall photograph and optical microscope images of a sub-10 nm slot antenna array, featuring a 20 μm × 80 μm rectangular structure, fully fabricated using 50 nm-thick Ag on a 4-inch Si wafer. The successfully fabricated sub-10 nm slot antenna array highlights the effectiveness of the improved approach for wafer-scale nanogap structures, offering a visible alternative to costly and restrictive methods, such as NIL and EUV lithography. To clearly observe the fabricated nanogap structures, field emission-electron microscope (FE-SEM) and spherical aberration-corrected transmission electron microscope (Cs-TEM) measurements were conducted. Figure 2a and b showcase a well-defined rectangular array with cleanly fabricated features. Moreover, a nanogap within the dotted box region in Fig. 2b was further examined in higher-magnification top-view (Fig. 2c) and cross-sectional (Fig. 2d) images, confirming the precise formation of nanogaps along the designed pattern. In Fig. 2e and f, TEM measurements at higher magnification were used to accurately observe and define the gap width. The nanogap was found to be perfectly perpendicular to the substrate, with the underlying Al₂O₃ layer beneath the secondary Ag layer and slight substrate etching evident due to the fabrication process. Additionally, Fig. 2f, a magnified view of the dotted box region in Fig. 2e, confirms that the gap width is approximately 5 nm.

Electron microscopy observations of nanogaps. (a–d) FE-SEM images of a nanogap slot antenna array. (a, b) Top-view images of the array, and (c, d) higher-magnification top-view and cross-sectional images of the nanogap highlighted by the dotted box in (b). (e, f) The cross-sectional images of a nanogap obtained using Cs-STEM images acquired at magnifications of (e) 200k and (f) 500k. The image in (f) corresponds to the dotted square box in (e). The formation of 5 nm nanogaps is clearly visible.

A key innovation in our approach is the direct use of the photoresist pattern as both a protective mask and a sacrificial layer during fabrication. While plasma etching and ALD processes are typically unsuitable for photoresist polymers due to hardening and deformation under high-temperature conditions, the fabrication of the slot antenna array demonstrated that the photoresist pattern remained largely intact during both the Ar ion beam milling and ALD steps. Moreover, the sub-10 nm slot antenna array was successfully achieved following the KOH solution treatment and lift-off process. To provide a detailed illustration of the fabrication steps, SEM measurements were conducted at each stage, utilizing a 100 nm-thick Au layer and a 50 nm-thick Al₂O₃ layer on a 300 nm-thick SiO₂/Si substrate, as shown in Fig. S2. After the secondary Au deposition, the overall structure remained stable, as depicted in Fig. S2a and S2b, indicating that the photoresist pattern was well-preserved during the ion beam milling process. It is important to note that, unlike reactive ion etching (RIE), the ion beam milling process exhibits strong directionality, enabling anisotropic etching of the metal layer32, Thus, the second Ar ion beam milling selectively etches the Au on the sidewalls of the photoresist pattern, while the Au layers on top of the photoresist and on the substrate remain largely intact, with negligible etching (Fig S2c). Furthermore, despite undergoing the second ion beam milling, KOH treatment, and lift-off processes, the nanogap structure shown in Fig. S2d was fabricated perfectly without any significant deformation. This demonstrates that a photoresist pattern can serve directly as both a protective mask and sacrificial layer for the ALL method, highlighting its versatility and robustness in nanoscale fabrication.

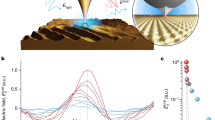

To statistically assess the uniformity of the fabrication across the entire wafer, the optical properties of the slot antenna array in the THz regime were measured after dicing the wafer into 1 cm² square chips (Fig. S1b). Given the clear correlation between slot width and THz resonance33, THz-TDS measurements were performed using a Ti: Sapphire femtosecond laser to generate and detect the THz waves (Fig. S3a). Figure 3a shows the THz transmission spectrum, with a resonance at 0.36 THz for the 5 nm gap width slot antenna array observed in Fig. 2. To further investigate the THz resonance behavior of the slot antenna array, COMSOL simulations were conducted for various structural configurations, with nanogap widths ranging from 3 to 8 nm, as shown in Fig. 3b. The simulation results for 5 nm show good agreement with the experimental results. Additionally, as the nanogap width increases, the THz resonance shifts to higher frequencies, accompanied by an increase in transmission. Through the analysis of the COMSOL simulations, we examined the THz-TDS measurements of the 57 diced chips and analyzed the nanogap sizes, as shown in Fig. S3b and Fig. S7in Supplementary Materials 2. As a result, the nanogap size on the wafer was found to increase from 3 nm at the wafer edge to 7 nm at the center. Considering that the nanogap size is primarily determined by the thickness of the Al₂O₃ layer in the ALD process, the slight variations in the nanogap structures are likely attributed to incomplete optimization of the ion milling process34. Due to the decreasing milling rate from the center to the edge of the wafer in the ion beam etching process, the Si beneath the Ag in the central region of the sample may be etched more extensively after complete removal of the Ag layer. Furthermore, the milling rate typically varies depending on the material, suggesting that the edges of the photoresist pattern may be slightly altered by the non-uniformity of the ion beam milling. This could lead to a shadowing effect during ALD and the second metal deposition, resulting in a broader gap width, as shown in Fig. S4. To minimize gap width variation in future processes, it is recommended to optimize plasma uniformity in an etching process. Nevertheless, all slot antennas fabricated across the wafer exhibited sub-10 nm widths, demonstrating a 100% yield using the advanced method. Furthermore, with complete process optimization, it is anticipated that exceptionally precise and highly uniform sub-10 nm structures with meticulously defined patterns can be consistently achieved across the entire wafer, marking a significant advancement in nanofabrication.

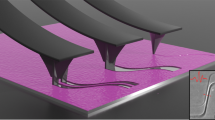

As mentioned above, the advanced ALL method overcomes limitations faced by earlier ALL techniques, which relied on mechanical stripping or chemical etching35,36. Figure 4 demonstrates the use of a combination of Ag and Cu to fabricate the same slot antenna array (Fig. 4a) and wafer-scale long slits (Fig. 4b), showcasing the incorporation of Cu—a metal previously incompatible with earlier ALL fabrication methods. The step-by-step fabrication process for the infinitely long slits is illustrated in Fig. S4. Compared to earlier ALL approaches, the improved method successfully enables the creation of long lines over large areas while accommodating both challenging metal species. This highlights the versatility of the advanced approach, enabling the use of various metals and the creation of large-scale patterns with sub-10 nm nanogaps. As the nanogap width decreases to sub-10 nm scales, quantum effects become more pronounced, enabling transformative applications such as surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS), gas sensing, and optical rectification12,37,38,39. Building on the results of Ag-Cu utilization in the improved approach, the versatility of incorporating various metal species was further demonstrated. Additionally, directly applying the photoresist pattern onto nanogap structures enables the creation of diverse patterns with nanogap features40,41. Figure 5a illustrates an electrode pad array with a 6 nm gap width, composed of Ti and platinum (Pt) at the wire center. The fabrication process for this electrode pad array follows the approach used for the Ag-Cu nano-slits shown in Fig. 4c and d. After forming infinitely long nano-slits composed of Au/Ti and Pt layers, additional dumbbell-shaped photoresist patterns were introduced on top of the nano-slits, as depicted in Fig. S6. To prevent oxidation and reduce contact resistance, the Ti layer was coated with an Au layer. Figure 5b presents an optical microscope image of an electrode pad pattern outlined by the white dotted box in Fig. 5a, confirming the successful fabrication of an electrode bridge with the nanogap region at the center. Furthermore, the FE-SEM images in Fig. 5c and d clearly reveal a 6 nm gap with higher magnification. Notably, since the fabrication process for Ti and Pt was not fully optimized, the Au/Ti and Pt layers in the FE-SEM image exhibit imperfect vertical profiles within the gap, indicating a lower yield. Nevertheless, by incorporating this post-processing step, the ALL method further expands its applicability in creating intricate patterns with sub-10 nm structures. This demonstration highlights the potential of the advanced ALL technique, integrated with additional patterning, for broad applications in optoelectronics and molecular sensing42,43.

Sub-10 nm nanogap structures composed of Cu and Ag: (a, b) Nanogap slot antenna array and (c, d) infinitely long slits. These structures demonstrate the potential to use corrosion-susceptible metals and offer increased flexibility for large-scale patterns across the entire wafer. The images in (b) and (d) correspond to the dotted boxes in (a) and (c), respectively.

(a) Mass production of Au/Ti-Pt nanogaps with a dumbbell-shaped array on a sapphire wafer. (b–d) An Au/Ti-Pt wire featuring a 6 nm nanogap at its center, observed using (b) an optical microscope and FE-SEM measurements captured at magnifications of (c) 45k and (d) 100k. The Au layer prevents oxidation of the Ti layer. The dumbbell-shaped array was fabricated through an additional post-process following the fabrication of nanogap slits, as illustrated in Fig. S6.

Fabricating sub-10 nm structures on a large-scale is essential for advancing a wide range of technologies, enabling unique quantum effects and high-density integration for the next generation devices. It is worth noting that conventional UV lithography, typically achieving micron-scale patterning, was employed in this study. Importantly, the advanced ALL method offers flexibility, facilitating the integration of other techniques, such as NIL, EUV, and deep UV (DUV) into the initial step to support the fabrication of dense, fine-featured devices27. Additionally, the nanogap structures without adhesion layer can be transferred onto various substrates, enabling heterostructure-based nanogap applications44. This adaptability makes the advanced ALL method even more versatile and suitable for a wide range of research and industrial applications. For instance, our advancements offer significant advantages in addressing challenges associated with metal-insulator-metal (MIM) diodes, which are essential components in optical rectenna and display industry45. Particularly, the precise control over sub-10 nm vertical structures afforded by the advanced ALL method allows for the fabrication of ultra-thin insulating layers in MIM diodes with vertical profiles, essential for achieving the high tunneling current densities required for efficient optical rectification14. As a result, by leveraging the merit of this method, there is great potential to develop a scalable MIM diode capable of generating substantial current46.

Conclusion

In summary, remarkable enhancements of the ALL method were demonstrated by successful fabrication of a sub-10 nm slot antenna array across the entire wafer. This improved method, utilizing the photoresist pattern as both a protective and sacrificial layers, demonstrates its competence to surpass the shortcomings of prior approaches by fabricating sub-10 nm structures that were previously unattainable. Additionally, with the key innovation in post-process, the method further extends its capability and suitability compared to other techniques. Consequently, the advanced ALL method establishes itself as a compelling solution for fabricating sub-10 nm structures, providing not only cost-effective, large-area manufacturing with high yields, but also appreciable advantages for both research and industrial society.

Data availability

If you want to request the experimental information and data presented from this study, please contact the corresponding author.

References

Zhang, H. et al. Sub-5 Nm monolayer MoS2 transistors toward low-power devices. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 3, 1560–1571. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaelm.0c00840 (2021).

Luo, S., Hoff, B. H., Maier, S. A. & de Mello, J. C. Scalable fabrication of metallic nanogaps at the Sub-10 nm level. Adv. Sci. 8, 2102756. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202102756 (2021).

Barnes, W. L., Dereux, A. & Ebbesen, T. W. Surface plasmon subwavelength optics. Nature 424, 824–830. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01937 (2003).

Vendamani, V. S., Rao, S. V. S. N., Pathak, A. P. & Soma, V. R. Silicon nanostructures for molecular sensing: A review. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 5, 4550–4582. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.1c04569 (2022).

Hugall, J. T., Singh, A. & van Hulst, N. F. Plasmonic cavity coupling. ACS Photonics 5, 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.7b01139 (2018).

Chen, X., Ciracì, C., Smith, D. R. & Oh, S. H. Nanogap-Enhanced infrared spectroscopy with template-stripped Wafer-scale arrays of buried plasmonic cavities. Nano Lett. 15, 107–113. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl503126s (2015).

Loganathan, K. et al. Rapid and up-scalable manufacturing of gigahertz nanogap diodes. Nat. Commun. 13, 3260. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30876-6 (2022).

Kang, J. H., Kim, D. S. & Seo, M. Terahertz wave interaction with metallic nanostructures. Nanophotonics 7, 763–793 (2018).

Kim, D. et al. Giant field enhancements in ultrathin nanoslots above 1 Terahertz. ACS Photonics. 5, 1885–1890. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.8b00151 (2018).

Runge, M. et al. Spatial distribution of electric-field enhancement across the gap of terahertz bow-tie antennas. Opt. Express 28, 24389–24398. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.399462 (2020).

Lim, D. K., Jeon, K. S., Kim, H. M., Nam, J. M. & Suh, Y. D. Nanogap-engineerable Raman-active nanodumbbells for single-molecule detection. Nat. Mater. 9, 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat2596 (2010).

Lee, J. et al. Advancements of intense terahertz field focusing on metallic nanoarchitectures for monitoring hidden interatomic gas-matter interactions. Adv. Mater. 36, 2308975. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202308975 (2024).

Lee, G., Roh, Y., Rho, E. Y., Ryu, Y. S. & Seo, M. Sensitive [invited]etection and [invited]valuation of ultrafine [invited]ust particles with a resonant terahertz metasurface [invited]. Opt. Mater. Express 13, 2563–2571. https://doi.org/10.1364/OME.497026 (2023).

Belkadi, A., Weerakkody, A. & Moddel, G. Demonstration of resonant tunneling effects in metal-double-insulator-metal (MI2M) diodes. Nat. Commun. 12, 2925. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23182-0 (2021).

Cattoni, A. et al. Sub-10 nm electron and helium ion beam lithography using a recently developed alumina resist. Microelectron. Eng. 193, 18–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mee.2018.02.015 (2018).

McMullen, R., Mishra, A. & Slinker, J. D. Straightforward fabrication of sub-10 nm nanogap electrode pairs by electron beam lithography. Precis. Eng. 77, 275–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precisioneng.2022.06.004 (2022).

Li, H., Wani, I. H., Hayat, A., Jafri, S. H. M. & Leifer, K. Fabrication of reproducible sub-5 nm nanogaps by a focused ion beam and observation of Fowler-Nordheim tunneling. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 103108 (2015).

Maruyama, N. et al. Advances and applications in nanoimprint lithography. Novel Patterning Technol. 2023. 12497, 86–97 (2023).

Kaiser, W. The evolvement of lithography optics towards advanced EUV lithography: Enabling the continuation of Moore’s law for six decades. IEEE Electron. Devices Mag. 2, 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1109/MED.2023.3343627 (2024).

Jeon, H. J., Lee, E. H., Yoo, H. W., Kim, K. H. & Jung, H. T. Fabrication of sub-20 nm nano-gap structures through the elastomeric nano-stamp assisted secondary sputtering phenomenon. Nanoscale 6, 5953–5959 (2014).

Fu, N., Liu, Y., Ma, X. & Chen, Z. EUV lithography: State-of-the-art review. J. Microelectron. Manuf. 2, 1–6 (2019).

Luo, S., Hoff, B. H. & deMello, J. C. Spontaneous formation of nanogap electrodes by self-peeling adhesion lithography. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 6, 1900243. https://doi.org/10.1002/admi.201900243 (2019).

Loganathan, K. et al. 14 GHz Schottky diodes using a p-doped organic polymer. Adv. Mater. 34, 2108524. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202108524 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. Atomic layer lithography of wafer-scale nanogap arrays for extreme confinement of electromagnetic waves. Nat. Commun. 4, 1–7 (2013).

Jeong, J., Rhie, J., Jeon, W., Hwang, C. S. & Kim, D. S. High-throughput fabrication of infinitely long 10 nm slit arrays for terahertz applications. J. Infrared Millim. Terahertz Waves 36, 262–268 (2015).

Williams, K. R., Gupta, K. & Wasilik, M. Etch rates for micromachining processing-Part II. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 12, 761–778. https://doi.org/10.1109/JMEMS.2003.820936 (2003).

Kim, S. et al. Broadband high-performance Terahertz polarizer based on a dense array of 5 nm gap slit antennas. Opt. Express 30, 30038–30046. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.460859 (2022).

Kim, Y., Yi, M., Kim, B. G. & Ahn, J. Investigation of THz birefringence measurement and calculation in Al2O3 and LiNbO3. Appl. Opt. 50, 2906–2910. https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.50.002906 (2011).

Ordal, M. A., Bell, R. J., Alexander, R. W., Long, L. L. & Querry, M. R. Optical properties of fourteen metals in the infrared and far infrared: Al, Co, Cu, Au, Fe, Pb, Mo, Ni, Pd, Pt, Ag, Ti, V, and W. W Appl. Opt. 24, 4493–4499 (1985).

Blaber, M. G., Arnold, M. D. & Ford, M. J. Search for the ideal plasmonic nanoshell: The effects of surface scattering and alternatives to gold and silver. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 3041–3045. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp810808h (2009).

Grischkowsky, D., Keiding, S., van Exter, M. & Fattinger, C. Far-infrared time-domain spectroscopy with terahertz beams of dielectrics and semiconductors. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 7, 2006–2015. https://doi.org/10.1364/JOSAB.7.002006 (1990).

Abraham-Shrauner, B. & Jagannathan, N. Modification of plasma-etched profiles by sputtering. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 27, 668–675. https://doi.org/10.1109/27.774670 (1999).

Jeong, J. et al. Anomalous extinction in index-matched terahertz nanogaps. Nanophotonics 7, 347–354 (2018).

Li, B. et al. Deep UV hardening of photoresist for shaping of graphene and lift-off fabrication of back-gated field effect biosensors by ion-milling and sputter deposition. Carbon 118, 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2017.03.032 (2017).

Rhie, J. et al. Control of optical nanometer gap shapes made via standard lithography using atomic layer deposition. J. Micro/Nanolithography MEMS MOEMS 17, 023504 (2018).

Yoo, D. et al. High-throughput fabrication of resonant metamaterials with ultrasmall coaxial apertures via atomic layer lithography. Nano Lett. 16, 2040–2046. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b00024 (2016).

Duan, H., Hu, H., Kumar, K., Shen, Z. & Yang, J. K. W. Direct and reliable patterning of plasmonic nanostructures with Sub-10-nm gaps. ACS Nano 5, 7593–7600. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn2025868 (2011).

Mennemanteuil, M. M., Buret, M., Colas-des-Francs, G. & Bouhelier, A. Optical rectification and thermal currents in optical tunneling gap antennas. Nanophotonics 11, 4197–4208. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2022-0278 (2022).

Zhao, Q. et al. Wafer-scale and cost-effective manufacturing of controllable nanogap arrays for highly sensitive SERS sensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 3580–3590. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.1c22465 (2022).

Kim, S. et al. Defining the zerogap: Cracking along the photolithographically defined Au–Cu–Au lines with sub-nanometer precision. Nanophotonics 12, 1481–1489. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2022-0680 (2023).

Gour, J. et al. Wafer-scale nanofabrication of sub-5 nm gaps in plasmonic metasurfaces. Nanophotonics 13, 4191–4202. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2024-0343 (2024).

Phan, T. T., Tosa, T. & Majima, Y. 20-nm-nanogap oxygen gas sensor with solution-processed cerium oxide. Sens. Actuators B 343, 130098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2021.130098 (2021).

Barik, A., Chen, X. & Oh, S. H. Ultralow-Power electronic trapping of nanoparticles with Sub-10 nm gold nanogap electrodes. Nano Lett. 16, 6317–6324. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b02690 (2016).

Shu, Z. et al. Asymmetric nanofractures determined the nonreciprocal peeling for Self-Aligned heterostructure nanogaps and devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 1718–1726. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.1c19776 (2022).

Emeric, L., Deeb, C., Pardo, F. & Pelouard, J. L. Critical coupling and extreme confinement in nanogap antennas. Opt. Lett. 44, 4761–4764. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.44.004761 (2019).

Bareiß, M. et al. High-yield transfer printing of metal–insulator–metal nanodiodes. ACS Nano 6, 2853–2859. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn3004058 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This study contains the results obtained by using the equipment of UNIST Central Research Facilities (UCRF). We would like to thank the equipment operators for their wonderful cooperation. We also thank Dohee Lee, Hyeong Seok Yun and Jiyeah Rhie who paved the way before we begin full-scale research. We also would like to thank Suhyun Shin for giving valuable feedback on effective content delivery. This research was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (NRF-2015R1A3A2031768, RS-2024-00454894).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C. and S.K. designed the experiments, performed the overall experiments up to sample fabrication and measurements, and wrote the manuscript. G. L. performed COMSOL simulations. D.-S. K. acquired funding and supported the research. D. L. assisted with nanogap fabrication composed of different types of metals. S. K. made figures and supervised the project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cha, J., Lee, G., Lee, D. et al. A progressive wafer scale approach for Sub-10 nm nanogap structures. Sci Rep 15, 11323 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96200-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96200-6

This article is cited by

-

Discharge Characteristics of Dual Frequency Capacitively Coupled Argon Plasma by Collision-Radiation and Nonlinear Global Model

Plasma Chemistry and Plasma Processing (2025)