Abstract

The issue of insufficient physical activity(PA) among adolescents is increasingly prominent, and Physical literacy (PL) is considered an important determinant of PA. This study aimed to explore the interplay between school physical environment, classroom achievement emotions and PL among adolescents.1,020 junior and senior high school students from 12 schools in Liaoning Province participated in the study(mean age = 15.23 ± 1.63) years. The collected data were analyzed using SPSS 27.0 and AMOS26.0, independent sample t-tests, Pearson correlation, linear regression, structural equation model testing and mediation analysis were used to analyze the relationship between indicators. The findings indicated significant correlations existed among the school physical environment, classroom achievement emotions, and PL. Regression analyses showed that both the school physical environment and classroom achievement emotions significantly predicted PL. Structural equation modeling analysis demonstrated that the school physical environment directly influenced PL (β = 0.259, 95% CI [0.164, 0.370]. Furthermore, classroom achievement emotions mediated the indirect effect of the school physical environment on PL (β = 0.685, 95% CI [0.598, 0.774].This study provides evidence of the relationships among school physical environment, classroom achievement emotions, and PL. This study traces to the source both external environmental and internal psychological factors that promote adolescents’ PL. The findings suggest that creating diverse and suitable school physical environment, alongside positive classroom achievement emotions, constitutes an effective path for enhancing adolescents’ PL cultivation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

From 2014 to 2018, a Canadian research team conducted multiple surveys on adolescents’ PA using questionnaires. The findings revealed that only 27–33% of adolescents worldwide met the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation of at least one hour of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) per day1. Reports on PA levels among Chinese adolescents in 2016 and 2018 showed that adolescents achieved only 18.4% and 13.1% of the recommended levels, respectively2,3. Additionally, a recent domestic study found that only 5.65% of adolescents engaged in one hour of MVPA daily, with a gender disparity of 9.4% for boys and 1.9% for girls4. These statistics highlight that insufficient PA has become a norm among Chinese adolescents. This trend is accompanied by a progressively worsening decline in physical fitness levels and health issues. PA is critical for healthy growth and development during childhood and Adolescence5,6.The World Health Organization’s Global Recommendations on PA for Health advise that, for optimum physical and mental health, children and adolescents should engage in at least sixty minutes of MVPA daily7.Consequently, maintaining effective physical activity is a critical approach to addressing numerous health issues in adolescents.

Recently, the concept of PL has attracted increasing research attention in physical education (PE), sports participation and the promotion of PA8.To promote the benefits of achieving the worldwide PA recommendation, the Guidelines of Quality of Physical Education (QPE) state that PL is the foundation of PE, and the development of PL is crucial for adolescents in encouraging adolescents to participate in lifelong PA9.People with higher PL levels may have more confidence and ability to participate in various sports activities. In contrast, they may also have less PA10. PL and enjoyment are important factors that affect PA11.Therefore, addressing the issue of decreased PA among adolescents and improving their health need to start with PL. It is essential to further explore the external environmental and internal psychological factors that promote adolescents’ PL.

The International PL Association (IPLA) was founded in 2013 under the chairmanship of Whitehead and defined the concept of “PL.” Here, PL is defined as the motivation, confidence, physical ability, knowledge, and understanding that people need to attach importance to, and take part in PA in their life12. Whitehead emphasized that PL is not a fixed state but a dynamic process, which he termed the “PL Journey.” This journey begins at birth and ends at death13. The development of PL results from the combined influence of individual participation, the support of related personnel, and the facilitation of organizations and environments. During the first three stages of the PL journey (preschool, primary school, and secondary school), guidance and support from others are essential14. A person can only lay the foundation for PL during childhood and adolescence. This foundation allows for continuous development throughout their life, adapting to changes in both internal and external environments, while maintaining lifelong engagement in PA. PL can only truly play a significant role when it enters the school system, particularly during elementary and secondary education15. The school physical environment is a key element in cultivating adolescents’ PL. In creating learning environments for PL development, it is crucial to offer diverse opportunities for students to explore and choose different paths of PA16. According to the “Cultural Structure Three-Level Theory,” the school physical environment can be divided into three dimensions: the school material environment, the school institutional environment, and the school social environment17. The school institutional environment primarily refers to policies and systems that influence students’ PA, including the support and implementation of school sports-related policies and relevant educational systems. The school social environment encompasses factors such as the PE, exercise opportunities provided to students, peer support, teacher support, and societal norms. The school material environment refers to factors such as the availability and accessibility of sports facilities and equipment, the suitability of the campus environment, spatial and temporal resources, and funding for PA17.The school physical environment provides essential venues for PA. Additionally, our observation that students’ MVPA at school was associated with the school physical environment18. Individuals might not participate in PA without the understanding of PL, yet through participating in PA, they can develop as physically literate individuals19. Although the school physical environment establishes a connection to PL through PA, research on the external factors influencing adolescents’ PL is still lacking. Further evidence is needed to enhance the understanding and recognition of PL.

Emotions can influence students’ interest, participation, achievement, personal development, and the classroom atmosphere. They are central to psychological health and well-being, and represent one of the key educational outcomes20. Achievement emotions, in particular, are more suitable for comprehensively reflecting students’ psychological development and explaining the ambiguous relationship between achievement motivation and emotions21. Achievement emotions refer to emotions directly related to achievement activities (such as learning) or achievement outcomes (such as success and failure)20. In the context of PE, classroom achievement emotions are those experienced by students within the specific environment of PE. These emotions, which are related to achievement activities (such as learning) or achievement outcomes (such as success and failure), can be categorized into eight distinct types: hope, pride, enjoyment, anxiety, shame, anger, despair, and boredom22. PE as an essential component of the social environment within the school physical environment, provide a place for students to engage in PA17. According to Control-value theory of emotions, the effect of social aspects of the classroom environment, including teacher interpersonal behavior, may in part affect student emotions via their goal orientations23. Indeed, students’ pleasant emotions (enjoyment) are strongly associated with perceived teacher support and enthusiasm (i.e., high communion)24. In contrast, research clearly indicated that students experience unpleasant emotions (anxiety and boredom) when a teacher is perceived as cold or excessively demanding25. However, there remains a paucity of research on school physical environment and classroom achievement emotions and further evidence is needed to advance our understanding on the associations among school physical environment and classroom achievement emotions.

The Active Health Kids Global Alliance (AHKGA) regards PE as an important indicator for assessing the school physical environment, which also illustrates the significant impact of PE on adolescents’ PA levels26. Through PE, it is crucial to improve the PL of every adolescent27.PE is an ideal environment to providing opportunities for human interactions that foster PE, through fair play affiliation, and cooperative learning activities28.Due to its extensive reach, PE in school is an important avenue for investigation of the connection between emotions and PL29. If PL is a pivotal precursor to PA, health, and well-being, and emotions may be critical activators or deactivators of PL processes, it follows that emotional experiences during movement, sport, recreation, and leisure activities merit careful research attention29,30. Drawing from the suggestions of Simonton and Garn, we have adopted the Control-Value Theory of Achievement Emotions as a grounding for examining the affective factors associated with the PL cycle proposed by Cairney et al. and elaborated upon by Houser and Kriellaars30,31,32. Thus, the role of classroom achievement emotions in the relationship between school physical environment and adolescent PL warrants further exploration. Based on the theoretical foundations mentioned above, the following hypotheses are proposed: H1: The school physical environment positively promotes adolescents’ PL; H2: Classroom achievement emotions positively promotes adolescents’ PL; H3: The school physical environment positively promotes classroom achievement emotions; H4: Classroom achievement emotions mediate the relationship between the school physical environment and adolescents’ PL.

Research samples and methods

Participants

This study was a survey conducted in September 2024. A total of 12 middle and high schools in Liaoning Province were selected as study sites. From each school, one class was randomly chosen from each of the following grades: seventh grade, eighth grade, tenth grade, and eleventh grade. This process resulted in a total of 1,020 students from both middle and high schools participating in the study. The survey utilized an electronic questionnaire, which was designed to collect data in four sections: (1) participants’ demographic information, (2) school physical environment, (3) classroom achievement emotions, and (4) PL. Data were gathered using this comprehensive questionnaire to examine the variables of interest.

Study procedure

All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki-Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects and other relevant laws,, regulations and ethical norms. Prior to the investigation, informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians. The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong First Medical University (Approval No. R202411200201). Subsequently, the study plan was reviewed and approved by the principals of the participating schools. Formal written consent was obtained from the principals. The research content was communicated to parents and participants through written notifications and parent information groups. After receiving the information, participants’ legal guardians were provided with an online consent form. The form included an introductory section explaining the study’s basic details. Guardians could provide consent for both their children and themselves at their discretion. At the beginning of the online agreement, participants were also presented with a written description of the study and were asked to confirm their willingness to participate. Both participants and their parents were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time without any consequences. All participants and their legal guardians provided informed consent prior to participation. Before distributing an online questionnaire, teachers received standardized training on how to guide participants. Teachers then provided additional instructions via parent information groups before sending the formal online questionnaire to the groups. With teacher guidance, participants completed the questionnaires. A total of 1,020 questionnaires were distributed, and 1,008 were returned, resulting in a response rate of 98.82%. After excluding 13 questionnaires with missing answers or obvious response patterns (e.g., extreme answering tendencies), 995 valid questionnaires were included, yielding an effective rate of 98.71%. The sample included 406 males (40.80%) and 589 females (59.20%). Participants were distributed across grades as follows: 234 in seventh grade (23.52%), 202 in eighth grade (20.30%), 221 in tenth grade (22.21%), and 338 in eleventh grade (33.97%). The mean age of participants was (15.23 ± 1.63) years.

Measurement

Tools Structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted using AMOS 26.0. Researchers followed the two-step approach proposed by Anderson et al.33. First, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to evaluate the validity of the measurement model. Second, SEM was used to analyze model fit and path coefficients. During CFA, items with standardized factor loadings below 0.5 were excluded to improve the model fit of latent variables33. A model was considered a good fit if the following criteria were met: χ²/df < 5, RMSEA < 0.08, and NFI, CFI, IFI, and GFI > 0.9034.

-

1.

School Physical Environment Scale The School Physical Environment Scale was developed based on prior research, including studies by the Active Healthy Kids Global Alliance (AHKGA)35. It assesses three dimensions of the school environment: institutional, social, and material environments. The scale was adapted by Guo Kelei17 and validated for reliability and validity. It contains 34 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). Higher scores indicate a greater recognition of the school physical environment by students17. All items were retained for final SEM analysis based on CFA standards. The model fit indices were as follows: χ2/df = 4.979, NFI = 0.945, IFI = 0.955, CFI = 0.955, RMSEA = 0.064. The overall Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.985.

-

2.

Classroom Achievement Emotions Scale The Achievement Emotions Questionnaire (AEQ) developed by Pekrun et al.36 was used to measure discrete achievement emotions in three academic contexts: classroom, learning, and exams. The AEQ includes eight subscales assessing discrete emotions: enjoyment, hope, pride, shame, anger, anxiety, despair, and boredom. The version adapted by Li Yangyang22 for PE contexts was used in this study and validated for reliability and validity. The Classroom Achievement Emotions Scale consists of 56 items across eight dimensions. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). Higher scores indicate greater levels of classroom achievement emotions among adolescents. All items were retained for SEM analysis. The model fit indices were: χ²/df = 4.265, NFI = 0.975, GFI = 0.937, CFI = 0.981, RMSEA = 0.058. Cronbach’s α for each subscale was 0.977.

-

3.

PL Scale This scale is based on Whitehead’s definition of PL, which encompasses four dimensions: motivation and confidence, physical competence, knowledge and understanding, and daily behavior37. The version adapted by Zhang Siqi38 for middle school students was used and validated for reliability and validity. The PL Scale includes 22 items across three dimensions: literacy knowledge, behavioral performance, and health-related physical fitness. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). Higher scores reflect greater levels of PL. All items were retained for SEM analysis. The model fit indices were: χ²/df = 4.281, NFI = 0.981, GFI = 0.950, CFI = 0.985, RMSEA = 0.058. The overall Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.983.

Data analysis

The primary variables were analyzed using SPSS 25.0, including descriptive statistics, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), correlation analysis, and regression analysis. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted using AMOS 26.0.Structural equation modeling (SEM) was selected to test the hypothesized mediation model, as its ability to test complex, multivariate relationships between multiple observed and latent variables. The estimation method used in this study was Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE), and both observed and latent variables were incorporated in the model. Latent variables, such as classroom achievement emotions, were estimated through multiple indicators, allowing for a more precise measurement of underlying constructs. First, model fit indices and relationships between path coefficients were tested. Second, the indirect effects of influencing factors were measured using a bias-corrected bootstrap method with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Indirect effects were considered statistically significant if the path coefficients did not include zero within the confidence interval.

Results

One-way analysis of variance for demographic characteristics and PL

The one-way analysis of variance revealed significant differences in PL scores across various demographic characteristics, including grade level, school location, constitution, exercise frequency, dietary habits, and family support for activities (p < 0.05). Higher PL scores were primarily observed among the score of in 7th grade was 4.228 ± 0.858, the score of attending schools located in urban areas was 4.103 ± 0.823, the score of with normal body composition was 4.098 ± 0.785, the score of engaging in higher exercise frequency was 4.289 ± 0.829, the score of reporting never being picky eaters was 4.224 ± 0.902, and the score of having significant family support for activities was 4.337 ± 0.803. Detailed results are presented in Table 1.

Correlation analysis between dimensions

As shown in Table 2, significant positive correlations were observed between the dimensions of the school physical environment (institutional, social, and material environments) and the dimensions of PL (knowledge, behavioral performance, and health-related physical fitness) p < 0.001). Similarly, positive correlations were found between the classroom achievement emotions of enjoyment, hope, and pride and the dimensions of the school physical environment (institutional, social, and material environments). These emotions also exhibited significant positive correlations with the dimensions of PL, including knowledge, behavioral performance, and health-related physical fitness (p < 0.001). Conversely, negative correlations were observed between the classroom achievement emotions of anger, anxiety, and despair and the dimensions of the school physical environment (institutional, social, and material environments). These emotions were also negatively correlated with PL dimensions such as knowledge and health-related physical fitness (p < 0.001). In addition, the classroom achievement emotions of shame and boredom were negatively correlated with the institutional and material dimensions of the school physical environment. These emotions also showed significant negative correlations with the health-related physical fitness dimension of PL (p < 0.001).

Linear regression analysis of factors influencing adolescents’ PL

A linear regression analysis was conducted to explore the predictive effects of classroom achievement emotions and the school physical environment on adolescents’ PL. This analysis controlled for grade level, school location, constitution, weekly exercise frequency, dietary habits, and the level of family support for activities. The results, presented in Table 3, indicate that both classroom achievement emotions and the school physical environment significantly predict adolescents’ PL. Among these, the school physical environment emerged as the strongest predictor, accounting for 29.1% of the variance in adolescents’ PL.

Structural equation model testing

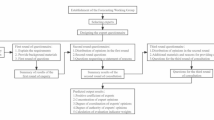

The fully mediated hypothesis model was constructed using AMOS 26.0, assuming that the school physical environment directly predicts PL, while classroom achievement emotions serve as a mediator, resulting in an indirect predict on adolescents’ PL (see Fig. 1). In AMOS 26.0, the model fit indices were as follows: χ2/df = 3.680, NFI = 0.992, IFI = 0.994, CFI = 0.994, and RMSEA = 0.052, indicating an excellent model fit.

From Fig. 1; Table 4, it is evident that: (1) The school physical environment has a significant promoting effect on classroom achievement emotions, with a standardized regression coefficient of 0.804 (p < 0.001). Thus, Hypothesis H1 was supported. (2) Classroom achievement emotions has a significant promoting effect on adolescents’ PL, with a standardized regression coefficient of 0.716 (p < 0.001). Therefore, Hypothesis H2 was supported. (3) The school physical environment has a significant promoting effect on adolescents’ PL, with a standardized regression coefficient of 0.218 (p < 0.001). Consequently, ypothesis H3 was supported.

The indirect predicts between variables were assessed using a bias-corrected bootstrap method with a 95% confidence interval (N = 2,000). As shown in Table 5; Fig. 1: Classroom achievement emotions mediated the relationship between the school physical environment and PL, with the specific pathway being: The direct predicts of school physical environment on PL was 0.259(95% CI: 0.164–0.370). In addition, the mediating predict of classroom achievement emotions on school physical environment and PL were 0.685(95% CI: 0.598–0.774).Therefore, classroom achievement emotions play a partially mediating role between PA and mental health, thus supporting Hypothesis H4.

Discussion

This study examined the relationships between the school physical environment, classroom achievement emotions, and PL among Chinese adolescents, focusing on the mediating role of classroom achievement emotions. The findings indicate that the school physical environment has a significant direct predict on PL and an indirect predict mediated by classroom achievement emotions. These results provide new insights into how external environments and psychological factors jointly influence adolescents’ PL.

This study further demonstrated that the school physical environment was positively correlated with PL and served as an independent variable to effectively predict PL, school physical environment has confirmed as an external environmental factor promoting PL. This aligns with Whitehead’s theory of PL, which emphasizes that the development of PL is inseparable from appropriate external environmental support39.The physical and social environment (context) will influence opportunities for engagement in PA, thereby influencing the impact PL may have on participation40,41. The school physical environment not only provides material resources for PA (e.g., facilities and equipment) but also shapes adolescents’ behaviors and attitudes through its social and institutional dimensions16,17. Specifically, the richness of the material environment can directly influence students’ willingness to participate in PA. In contrast, the institutional and social environments foster comprehensive PL development by motivating and engaging students in PA. PL is important for sustained participation in PA, but development of PL also occurs through both unstructured (i.e. free play, recreational pursuits) and structured PA (e.g. sport, PE)30. Indeed, there is evidence to show that a higher frequency of participation in sport increases active free play, suggesting the possibility that skills learned in sport may promote greater participation in active free play42. The degree of policy support and implementation within the school physical environment is directly linked to students’ participation in PA. Factors such as the availability of free play or recreational time during school breaks, access to PA facilities and equipment, the frequency of sports programs, and support from school leaders, teachers, and peers all play critical roles in fostering adolescents’ PL. These findings demonstrate the multidimensional nature of the influence of the school physical environment on PL. The school physical environment is not only a carrier space for PA but also a key catalyst in cultivating PL.

The results of this study confirm that the classroom achievement emotions, (e.g., hope, pride, and enjoyment )significantly predict PL levels, classroom achievement emotions have confirmed as an internal psychological factor promoting PL. This finding aligns with Pekrun’s control-value theory of emotions, which posits that positive achievement emotions increase students’ motivation and performance in achievement activities20. The most studied discrete negative emotions in the PE contexts are boredom and anxiety with them showing a negative relationship to task goals43,44. In this study, the positive effects of classroom achievement emotions on adolescents’ PL can be attributed to the coexistence of the prevalence of co-occurring positive and negative emotions (mixed emotions). Indeed 94% of the students with mixed emotions had a positive aggregate emotional score indicating that negative emotions may not have precluded a positive experience29. enjoyment is an important motivation to participate in PA during PE5. Positive emotions further enhance students’ intrinsic motivation to learn PL-related knowledge, skills, and healthy behaviors. The emotional support and quality of teacher-student interactions during PE is crucial factors influencing students’ achievement emotions. For instance, studies have shown that when students perceive greater teacher support and enjoy classroom activities, they are more likely to exhibit positive emotional states, leading to increased confidence and satisfaction during PA31. These improvements positively contribute to students’ PL, including their knowledge, skills, and health-related behaviors. In conclusion, this study has shown the importance that achievement emotions play in predicting outcomes in PE, such as the intention to be physically active(IPA) in the future and academic achievement44, PL as the primary learning outcome of PE21, in future PE should the cultivation of adolescents’ PL should fully take into account the important role of achievement emotions. It is essential to create a positive emotional atmosphere in the classroom, allowing students to immerse themselves in an enjoyable PE experience, thereby enhancing their PL from internal.

The findings of this study confirm that the school physical environment has a significant predict on classroom achievement emotions. Especially, factors in the school social environment (e.g., format of PE, peer support, teacher support, etc.) play a significant role in promoting classroom emotions. This result aligns with the control-value theory of emotions, which identifies the social environment of the classroom as a basic antecedent of student emotions46. Research has demonstrated that execution of motor performance on its own is insufficient for learning if it is not experientially linked with positive emotional states (enjoyment), which leads to a desire to repeat the skill and use it to engage in other activities such as sport (motivation), all within a particular social context or physical environment30. The school physical environment as an important factor in students’ MVPA levels28, the school physical environment can enhance students’ motivation by providing high-quality material resources, such as sports equipment and activity spaces. Achievement emotions are closely linked to an individual’s learning motivation46. When external environmental stimuli trigger learning motivation, students are better able to regulate their achievement emotions. In the school physical environment, these teacher behaviors can be assumed to impact students’ emotions (e.g., enhancing enjoyment, reducing boredom) in a very direct way by a so-called ‘‘emotional contagion’’ (e.g., humor and teachers’ own fascination leading to student enjoyment48,49. example, showed that high teacher enthusiasm positively impacted students’ enjoyment in class, and demonstrated that teacher enthusiasm is positively correlated with enjoyment and pride, and negatively correlated with anger and boredom in class50,51. Therefore, there is a close relationship between the school physical environment and achievement emotions in the classroom. It is essential to fully utilize the role of the school physical environment in influencing students’ participation in PE and PA. Teachers as a guide in arousing positive emotional engagement in students, which will promote lifelong participation in PA and the development of good PL.

Our results showed that classroom achievement emotions was a very important mediating factor in the relationship between the school physical environment and PL. The mediation effect accounted for 68.5% of the total effect. The school physical environment serves as a crucial setting for developing adolescents’ PL, and PE in school is an important avenue for investigation of the connection between emotions and PL29. PE, in particular, play a pivotal role as the primary setting where adolescents acquire PL knowledge, behavioral performance, and health-related physical fitness. Classroom achievement emotions play in predicting outcomes in PE44. Positive emotions promote favorable learning outcomes and contribute to the development of PL among adolescents. In contrast, negative emotions (e.g., anxiety, boredom, and shame) showing a negative relationship to task goals43. When students engage in PA with negative emotions, it is likely to impact their desire and motivation to learn PL knowledge and sports skills. The less they participate in PA, the more detrimental it becomes to the development of healthy behaviors. Therefore, it is crucial to fully explore the resources available within the school physical environment, such as equipment, teachers, and the content and timing of extracurricular activities. These resources can stimulate motivation for PA, generate positive emotions (such as enjoyment), and sustained participation in PA, fosters a lifelong sports thought and continuously enhances own PL.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, research on PL in China is still in its early stages, and variations exist across countries in the understanding and study of PL. Therefore, the findings of this study are primarily applicable to populations within educational systems similar to the one examined here. Second, the results are constrained by the regional nature of the sample and the cross-sectional study design, which may introduce biases. Third, while the findings of this study align with existing literature supporting the hypothesized relationships, the cross-sectional design necessitates further experimental research to validate the causal inferences observed.

Conclusion

This study examined the relationships among the school physical environment, classroom achievement emotions, and PL. By constructing a mediation model, the study revealed that the three variables are positively correlated, with classroom achievement emotions acting as a mediating factor. This means that even if there is a favorable school physical environment, students may not achieve satisfactory learning outcomes or develop their PL if they do not experience positive emotions in the classroom. Therefore, it is essential to provide adolescents with more exploratory environments, stimulate their motivation to participate, elicit positive emotions, and thereby develop the mindset and behaviors for lifelong engagement in PA. This study traces to the source both external environmental and internal psychological factors that influence adolescents’ PL. It offers a new perspective for research on PL in adolescents. As the field advances, future research endeavors could delve deeper into the impact of other factors (e.g., family physical environment and social physical environment) in adolescents’ PL. Additionally, in PE the influence of emotional changes on PL in adolescents’ PL further exploration. These issues are crucial for providing valuable insights into the development and enhancement of PL in adolescents.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Salome, A. et al. Global matrix 3.0 physical activity report card grades for children and youth: results and analysis from 49 countries. J. Phys. Act. Health 15 , S251–S273. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2018-0472 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Results from Shanghai’s (China) 2016 report card on physical activity for children and youth. J. Phys. Act. Health 13(s2), S124–S128. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2016-0362 (2016).

Liu, Y. et al. Results from China’s 2018 report card on physical activity for children and youth. J. Phys. Act. Health. 15(s2), S333–S334. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2018-0455 (2018).

Wang, C., Chen, P. & Zhuang, J. A National survey of physical activity and sedentary behavior of Chinese City children and youth using accelerometers. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 84(sup2), S12–S28. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2013.850993 (2013).

Flynn, M. A. T. et al. Reducing obesity and related chronic disease risk in children and youth: a synthesis of evidence with ‘best practice’ recommendations. Obes. Rev. 7(s1), 7–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789x.2006.00242.x (2005).

William, B. et al. Evidence based physical activity for school-age youth. J. Pediatr. 146(6), 732–737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.01.055 (2005).

World Health Organisation. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44399/1/9789241599979 (2010).

Lowri Cerys Edwards,Anna Bryant,Richard Keegan,Kevin Morgan, & Adam Jones. Definitions, Foundations and Associations of Physical Literacy: A Systematic Review. Sports Medicine, 47 (1), 113–126. (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0560-7

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Quality Physical Education: Guidelines for Policy Makers. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2015).

Cairney, J. et al. Towards a physical literacy framework to guide the design, implementation and evaluation of early childhood movement-based interventions targeting cognitive development. Ann. Sports Med. Res. 3(4), 1073–1071. null (2016).

Yan, W. et al. Association between enjoyment, physical activity, and physical literacy among college students: a mediation analysis. Front. Public. Health 11, 1156160. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2013.850993 (2023).

Jean de Dieu, H. & Zhou, K. Physical literacy assessment tools: a systematic literature review for why, what, who, and how. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 18(15), 7954. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157954 (2021).

IPLA. Physical literacy can be described as the motivation, confidence, physical competence, knowledge and Understanding to value and take responsibility for engagement in physical activities for life. https://www.physical-literacy.org.uk (2024.)

Whitehead, M. Stages in physical literacy journey. ICSSPE Bull.–J. Sport Sci. Phys. Educ. 2013, 65 (2013).

Ren, H. Physical literacy: a concept to integrate sport reforms and developments in contemporary era. China Sport Sci. 38(3), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.16469/j.css.201803001 (2018).

Chen, H. Y. Research on the perception-action theory of physical literacy cultivation—based on the analysis of ecological dynamics. J. Phys. Edu. 30(2), 41–48. https://doi.org/10.16237/j.cnki.cn44-1404/g8.2023.02.008 (2023).

Guo, K. L. Study on the relationship between physical education environment, exercise intention and physical activity of junior high school students. Shanghai Univ. Sport. https://doi.org/10.27315/d.cnki.gstyx.2019.000018 (2019).

Button, B., Trites, S. & Janssen, I. Relations between the school physical environment and school social capital with student physical activity levels. BMC Public. Health 13, 1–8 (2013).

Lloyd, M., Colley, R. C. & Tremblay, M. S. Advancing the debate on’fitness testing’for children: perhaps we’re riding the wrong animal. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 22(2), 176–182. https://doi.org/10.1123/pes.22.2.176 (2010).

Pekrun, R. The control-value theory of achievement emotions: assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 18, 315–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-006-9029-9 (2006).

Mouratidis, A. et al. Beyond positive and negative affect: achievement goals and discrete emotions in the elementary physical education classroom. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 10(3), 336–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2008.11.004 (2009).

LI, Y. Y. Origin of psychological factors in PE class for college students’ extracurricular exercise: also on the mediating effect of achievement emotions. J. Shenyang Sport Univ. 40(6), 34–42. https://doi.org/10.12163/j.ssu.20211123 (2021).

Pekrun, R., Elliot, A. J. & Maier, M. A. Achievement goals and discrete achievement emotions: a theoretical model and prospective test. J. Educ. Psychol. 98(3), 583–597. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.3.583 (2006).

Goetz, T. et al. Characteristics of teaching and students’ emotions in the classroom: investigating differences across domains. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 38(4), 383–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2013.08.001 (2013).

Goetz, T. et al. Intraindividual relations between achievement goals and discrete achievement emotions: an experience sampling approach. Learn. Instr. 41, 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2015.10.007 (2016).

Active Health Kids Global Alliance. Indicators and Evaluation Methods of the Physical Activity Assessment System for Children and Adolescents. http://www.activehealthykids.org/core-indicators-and-benchmarks/

UNESCO. Quality Physical Education–Guidelines for PolicyMakers 24 (Springer, 2015).

Castelli, D. M., Barcelona, J. M. & Bryant, L. Contextualizing physical literacy in the school environment: the challenges. J. Sport Health Sci. 4(2), 156–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2015.04.003 (2015).

Woolley, A., Houser, N. & Kriellaars, D. Investigating the relationship between emotions and physical literacy in a quality physical education context. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2024-0082 (2024).

Cairney, J. et al. Physical literacy, physical activity and health: toward an evidence-informed conceptual model. Sports Med. 49, 371–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01063-3 (2019).

Simonton, K. L. & Garn, A. Exploring achievement emotions in physical education: the potential for the control-value theory of achievement emotions. Quest 71(4), 434–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2018.1542321 (2019).

Houser, N. & Kriellaars, D. Where was this when I was in physical education?? physical literacy enriched pedagogy in a quality physical education context. Front. Sports Act. Living. 5, 1185680. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2023.1185680 (2023).

Anderson, J. C. & Gerbing, D. W. Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 103(3), 411. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411 (1988).

MacCallum, R. C. & Austin, J. T. Applications of structural equation modeling in psychological research. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 51(1), 201–226. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.201 (2000).

Active Kids Global Alliance. Evaluation indicators and methods for physical activity in children and adolescents. http://www.activehealthykids.org/core-indicators-and-benchmarks/ (2024).

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T. & Perry, R. P. Achievement emotions questionnaire (AEQ). User’s manual. Unpublished Manuscript, University of Munich, Munich (2005).

Tremblay, M. S. et al. Physical literacy levels of Canadian children aged 8–12 years: descriptive and normative results from the RBC learn to Play–CAPL project. BMC Public. Health. 18, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5891-x (2018).

Zhang, S. Q. Development of physical literacy assessment scale for junior high school students in Jiangsu Province. China Univ. Min. Technol. https://doi.org/10.27623/d.cnki.gzkyu.2023.001398 (2023).

Whitehead, M. Physical Literacy: Throughout the Life Course (Routledge, 2010).

Hulteen, R. et al. The role of movement skill competency in the pursuit of physical literacy: are fundamental movement skills the only pathway? J. Sci. Med. Sport 20, e77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2017.01.028 (2017).

Sallis, J. F. et al. Role of built environments in physical activity, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 125(5), 729–737. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.110.969022 (2012).

Cairney, J. et al. A longitudinal study of the effect of organized physical activity on free active play. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 50(9), 1772–1779. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0000000000001633 (2018).

Duda, J. L. & Nicholls, J. G. Dimensions of achievement motivation in schoolwork and sport. J. Educ. Psychol. 84(3), 290 (1992).

Hall, H. K. & Kerr, A. W. Motivational antecedents of precompetitive anxiety in youth sport. Sport Psychol. 11(1), 24–42. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.11.1.24 (1997).

Fierro-Suero, S. et al. Achievement emotions, intention to be physically active, and academic achievement in physical education: gender differences. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 42(1), 114–122. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2021-0230 (2022).

Sun, X. et al. Classroom social environment as student emotions’ antecedent: mediating role of achievement goals. J. Exp. Educ. 90(1), 146–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2020.1724851 (2022).

Schukajlow, S., Rakoczy, K. & Pekrun, R. Emotions and motivation in mathematics education: theoretical considerations and empirical contributions. ZDM-Math Educ. 49, 307–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-017-0864-6 (2017).

Hatfield, E., Cacioppo, J. T. & Rapson, R. L. Emotional contagion. Curr. Dir. Psychol. 2(3), 96–100. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139174138 (1993).

Mottet, T. P. & Beebe, S. A. Relationships between teacher nonverbal immediacy, student emotional response, and perceived student learning. Commun. Res. Rep. 19(1), 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824090209384834 (2002).

Frenzel, A. C. et al. Emotional transmission in the classroom: exploring the relationship between teacher and student enjoyment. J. Educ. Psychol. 101(3), 705. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014695 (2009).

Goetz, T. et al. The domain specificity of academic emotional experiences. J. Exp. Educ. 75(1), 5–29. https://doi.org/10.3200/jexe.75.1.5-29 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants for their efforts in our study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Z. wrote the main manuscript text, Y.Z.W. and C.K.L . collected and organized the data, X.Z., Y.Z.W. and C.K.L . analyzed the data prepared Tables 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5; figure1, I.Y. revised the manuscript . All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zang, X., Wang, Y., Lu, C. et al. Investigating the mediating role of classroom achievement emotions in the relationship between school physical environment and physical literacy of adolescents. Sci Rep 15, 11510 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96209-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96209-x