Abstract

Invasive snakes are among the most challenging invaders worldwide due to their exceptionally low detection rate and grave ecological impacts. Environmental DNA (eDNA) has emerged as a promising tool to improve invasive snake detection and enhancing management programs, yet its application to terrestrial snakes remains underexplored. This study provides the first advances in the use of eDNA techniques to detect the terrestrial invasive California kingsnake (Lampropeltis californiae). We designed L. californiae-specific primers and tested their effectiveness in detecting the species in different environmental samples, including swab samples from underneath artificial cover objects (ACOs) made of different materials, soil beneath ACOs, randomly collected soil, and researchers’ boots. Additionally, we conducted a controlled experiment to assess the accumulation and degradation rate of L. californiae eDNA over a 14-day period (7 with snakes in the terraria and 7 after having removed them). We detected L. californiae eDNA in 9.31% of swab samples, in 2.22% of soil samples under ACOs, and in 2.56% of boot samples, while no detections appeared in randomly collected soil or controls. In the controlled experiment, eDNA was undetectable in terraria prior snake introductions, but remained detectable throughout the study, with no evidence of snake eDNA degradation after snake removal. These findings provide key insights for the implementation of an eDNA-based protocol for the detection of L. californiae in Gran Canaria, offering a valuable tool for monitoring this invasive species. Furthermore, this study could be used for refining eDNA methodologies to detect other elusive terrestrial snake species elsewhere.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Reliable information on the presence and distribution of invasive species is crucial for the planning, prioritization and implementation of effective conservation actions at different invasion stages1,2, ultimately leading to cost-effective interdiction and eradication efforts3,4,5. Long-term management programs targeting established invaders also rely on precise knowledge of species presence and distribution, as it contributes to the assessment of management feasibility, the planning and prioritization of conservation actions, the evaluation of program development and the confirmation of invasive species removal5,6,7. However, ascertaining species presence and distribution can be time and resource-consuming7, and failing to do so can have dire consequences for conservation programs8,9,10,11. The utilisation of techniques for the detection of environmental DNA (eDNA) in natural environments offers a promising solution to these challenges. This approach overcomes the limitations associated with traditional sampling methods12,13 and facilitates the identification of species irrespective of their life stage or abundance14,15,16. However, the implementation of eDNA protocols is contingent, among others, on the development of specific primers for the target species, the adaptation of sampling protocols to its ecological characteristics, and the evaluation of the species DNA degradation in the environment12,13,17. These fundamental requirements ensure the specificity and sensitivity of eDNA techniques for the target species, thereby preventing management from being misled by faulty detection protocols12. Despite the substantial progress that has been made in this regard for aquatic species18, the application of eDNA for terrestrial organisms is still in its early stages19.

Invasive snakes are among the most challenging biological invaders, posing a serious threat to global conservation goals. The increasing number of snakes transported through unintentional and deliberate pathways20,21,22 has led to the numerous established populations worldwide23 that cause irreversible ecological and socioeconomic damages24. Consequently, conservation practitioners must develop effective strategies to address this challenge, though the elusiveness of terrestrial snakes poses significant obstacles to their effective surveillance and management8,25,26. The use of environmental DNA is a promising solution to this problem, yet its application in the field of terrestrial snake research also remains to be investigated27,28,29,30.

We initiated the implementation of eDNA techniques in the management of the terrestrial California kingsnake Lampropeltis californiae. This species was introduced to the island of Gran Canaria (Canary Islands, Spain) more than two decades ago31, and has notably expanded its range since then, outpacing management efforts to control its spread32,33. The species management has been largely hindered by the extremely low probability of detection and capture rate of L. californiae, as it is a fossorial species that spends most of its time concealed underground and exhibits ephemeral and low activity patterns on the surface34. The primary conservation objective in the region is to control the species’ expansion and prevent its spread to other islands, as L. californiae is causing severe ecological impacts35,36 that are transferable to other islands, given the archipelago’s high suitability for the species37. In addition, the high probability of the species being introduced in continental Europe has led to its inclusion in the List of Invasive Alien Species of European Concern (Regulation (EU) 2022/1203), which makes it also a conservation priority at the European level. In this context, the primary objectives of this study were to (1) design and validate specific primers for L. californiae, (2) evaluate various sampling methods for collecting and detecting L. californiae eDNA in the field, and (3) analyze L. californiae eDNA accumulation and degradation to inform detection protocols. The sampling and laboratory protocols developed could be useful and informative for the implementation of eDNA techniques in the detection of other terrestrial snakes elsewhere.

Methods

Design and validation of Lampropeltis californiae specific primers

We designed primers for the cytochrome c oxidase I subunit (COI ≈ 654 bp) of L. californiae to distinguish this species from the co-existing reptiles of Gran Canaria, specifically the Gran Canaria giant lizard Gallotia stehlini, the Gran Canaria skink Chalcides sexlineatus, and Boettger’s wall gecko Tarentola boettgeri. Lampropeltis californiae and T. boettgeri are listed as least-concern species at the UICN Red List, while G. stehlini is classified as critically endangered and C. sexlineatus as endangered38,39,40,41. We extracted these species DNA from small tail fragments (approximately 30 mg) of four L. californiae individuals originating from the four primary invaded areas of Gran Canaria33, as well as two individuals of each endemic reptile species (own samples, collected on previous field campaigns), stored in 95% alcohol at − 20 °C, available in our facilities at the CSIC (Tenerife, Canary Islands). Following the manufacturers’ protocols, we extracted genomic DNA from L. californiae using the commercial kit E.Z.N.A.® Tissue DNA (Omega Bio-tek Inc., USA), whereas we used ZR Genomic DNA Tissue MicroPrep Kit (Zymo Research, USA) to extract DNA from the endemic reptiles. We assessed DNA quantity and quality using a NanoDrop®ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

For COI amplification, we used the universal primers LCO1490/HCO219842 for all species except for T. boettgeri, for which we employed RepCOIF/RepCOIR primers43. We performed PCR reactions in a Bio-Rad T-100 Thermal Cycler (BioRad, USA) in a 25 µL reaction volume containing 2.5 µL of T10x PCR TaKaRa (15 mM MgCl2) (Takara Bio Inc., Japan), 2 µL of dNTP mix (2.5 mM) (Takara Bio Inc., Japan), 1 µL (0.5 µg) of bovine serum albumin (BSA, BioLine, UK), 0.125 µL of TaKaRa Taq (1.25 U/µL) (Takara Bio Inc., Japan), 0.8 µL (10 mM) of each primer, and 20 ng of the extracted DNA. The PCR conditions for L. californiae, G. stehlini and C. sexlineatus consisted of an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 1 min, followed by 35 amplification cycles (15 s at 94 °C, 20 s at 50 °C, 30 s at 72 °C) and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. For T. boettgeri, we performed a touchdown PCR with slight modifications to the conditions established by Velo-Antón et al.44: an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by an initial phase of 9 cycles (40 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 52 °C, decreasing by 0.5 °C per cycle to 48 °C, and 45 s at 72 °C), a second phase of 31 cycles (30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 48 °C, and 45 s at 72 °C), and a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. We visualized PCR products by electrophoresis on 1.7% agarose gel stained with Real-Safe (Real Biotech Corporation, Taiwan). We conducted the sequencing of fragments at the Genomic Service of the University of La Laguna. We aligned COI sequences (GenBank Accession numbers for species haplotypes: PQ870365, PQ867189, PQ867192, PQ867193, PQ870406) with available Lampropeltis sequences retrieved from GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and Bold Systems v3 (https://v3.boldsystems.org/) (see the Supplementary Information I) using ClustalW in MEGA X45. Given that shorter DNA sequences are more likely to persist in the environment and improve eDNA detection rates46, we used Primer-BLAST47 to design a short, species-specific sequence that distinguished L. californiae from endemic reptiles. We then tested primer specificity by amplifying previously extracted DNA from L. californiae and the endemic reptiles using the same PCR conditions as previously described, with an annealing temperature of 57 °C and the subsequent visualization of PCR products via 1.7% agarose gel electrophoresis stained with Real-Safe (Real Biotech Corporation, Taiwan).

Additionally, we amplified extracted DNA using quantitative PCR (qPCR) with 10–20 ng of DNA, 300 nM of each primer, and 7.5 µL of iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, USA) in a 15 µL reaction volume. We performed reactions on an iCycler BIO-RAD real-time thermal cycler at the Genomic Service of the University of La Laguna. In order to optimize amplification conditions, we first tested a gradient of temperatures and cycle numbers using L. californiae DNA as the positive control and a sample without DNA as the negative control. The final qPCR conditions comprised an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 amplification cycles (15 s at 95 °C, 20 s at 57 °C, and 30 s at 72 °C). We assessed primer specificity by comparing qPCR melting curves, ensuring that L. californiae-specific primers produced distinct melting curves, while non-specific amplification resulted in spurious curves for endemic reptiles.

Detection of Lampropeltis californiae eDNA in environmental samples

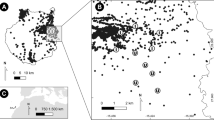

We conducted an eDNA detection field experiment in the surroundings of Cuevas de Calacio (Telde), an area occupied by L. californiae since 201733, primarily covered by native xeric shrublands48 and experiencing mild weather conditions49. We used QGIS 3.2050 to delineate three sampling sites of similar size (1.4 ha) where the highest concentration of L. californiae catches had occurred during the previous years, according to control program database33. These sites were located at least 120 m apart to account for the home range of L. californiae34 (Fig. 1). At each site, we established 15 random locations using the QGIS 3.34 random point generator50, separated a minimum of 20 m to avoid spatial overlap and based on the most frequently daily movements of L. californiae34. From May 4th to 5th 2022, we placed three of each of these artificial cover objects (ACOs) types in the generated random locations: plywood boards (1.22 × 0.80 m), corrugated bitumen sheets (1.20 × 0.70 m), corrugated steel plates (1.20 × 0.70 m), flat bitumen sheets with a reflective top side (1.00 × 1.00 m), and rubber sheets (1.00 × 1.00 m). To identify the most effective sampling approach to detect snake eDNA, we compared two sampling regimes. We executed the first one from January 30th to June 8th 2023, encompassing nine one-day sampling sessions, 30 days apart in January and February, and 15 days apart subsequently. During this period, we collected a swab sample from the underside of one randomly selected ACO from each type at each site, as well as from the soil immediately beneath the selected ACOs. Additionally, we collected soil samples at random locations that we placed prior to each sampling session using QGIS 3.20 random point generator50 and located at least 20 m away from each sampling point. During the initial period, we also collected swab samples from the soles of researchers’ boots at the end of each session to assess the viability of this technique as an alternative detection method. Despite the fact boots might not provide accurate location of eDNA presence, it could be used to detect the species in given areas by simply walking through them. We performed the second sampling regime from June 8th to June 30th, consisting of four one-day sampling sessions, seven days apart, during which we collected swab samples from all ACOs at each site.

(adapted from Matthias et al.30), and soil samples from the substrate directly under their corners and center. We also collected soil samples from random locations within each site > 20 m apart from each other and each ACO. The second inset shows the location of the Canary Islands and the island of Gran Canaria within the archipelago, as well the location of the study area (write cross) and Lampropeltis californiae accumulated captures and sightings from 2009 to 2024 according to the control program33 (black dots).

Map of the study area showing the location of our sampling sites and artificial cover objects (ACOs). We visited ACOs to collect swab samples following the patterns described in the top inset

We collected ACO swab samples following a protocol adapted from Matthias et al.30 and Kyle et al.19). We used sterile cotton discs previously moistened with 70% isopropanol, which we gently rubbed30 along a small square midway between the edge of the ACO and the center, starting at the top left, then making an “X” pattern connecting each corner, followed by a “+” pattern, and finishing with a square along the outer edges of each ACO30 (Fig. 1). We collected boot samples by gently rubbing a cotton disc over the entire surface of each team member boots’ soles at the end of each sampling session, with each boot sample being stored separately. Each soil sample consisted of a 50 mL Falcon tube filled with small amounts of soil collected by sliding the tube directly under the four corners and the center of the soil covered by each ACO and over an area equivalent to that of the ACO for random soil samples. At the end of each sampling session, we moistened a cotton pad with 70% isopropanol and stored these as negative field controls. We transported all samples back to the laboratory on the same day of sampling and stored them at − 20 °C in a freezer drawer that had not previously contained samples of the target species. In an effort to minimize contamination during the entire field sampling workflow51, we used new disposable latex gloves to collect each sample, stored all swab samples in individual paper envelopes, and separated each sample into small, individual, hermetic sealed plastic bags. We incorporated silica gel beads into the swab and boot bags with the objective of mitigating potential mold growth. Subsequent to the collection of samples, we consolidated the small individual plastic bags into larger hermetic bags for each sample type and site. No contact with the target species had occurred prior to or during the sampling day, since all sampling and personal material (in addition to the researchers) travelled to Gran Canaria from the uninvaded island of Tenerife for each sampling session.

We extracted DNA in a pre-PCR laboratory located in the CSIC facilities in Tenerife (no samples of the target species had been recently processed there) and following a specific protocol for each sample type. For swab samples, we separated the most superficial layer of the cotton disc using sterilized forceps and scalpels for each sample and placed it into a 1.5 mL tube. We conducted the procedure for soil samples in accordance with the protocol proposed by Matthias et al.30. We shook the samples and transferred 15 mL of their content to another 50 mL Falcon tube, which we then filled with ultrapure water (Ultra-Pure Water System, Milli-Q®, Merck, USA) up to 45 ml. We then inverted and shook vigorously the Falcon tube for c. 30 s. We left the tube in a vertical position at 4 °C for 24 h to allow the sample to settle. We transferred the supernatant to a sterile single-use 250 mL vacuum filtering funnel (Pall Life Science, USA), and used sterile cotton gauzes to separate larger stones and plant debris. We filtered the supernatant on a filtration ramp (Millipore®, USA) with 47 mm polystyrene membrane filters and 0.45 μm pores (Prat Dumas, France). We then extracted the filter from the ramp, cut a quarter of it, and placed this final sample in a 1.5 mL tube. We extracted the DNA retained in the cotton discs and in the filters using the commercial kit E.Z.N.A.® Tissue DNA (Omega, Bio-tek Inc., USA), following the manufacturer’s protocol. In this process, we ensured that the entire inner surface of the discs and filters were in contact with the lysis buffer. To amplify L. californiae eDNA, we employed the qPCR (utilizing the same conditions as previously described), due to its higher sensitivity to small-sized DNA fragments in comparison with conventional PCR, making it a more suitable for eDNA16,52,53. This technique is frequently employed for the detection of single species13,54, offering enhanced detection probabilities in comparison to metabarcoding for species-specific assays55,56. In accordance with the approach outlined by Dejean et al.57, we amplified three replicates of each sample, with the inclusion of positive and negative controls. We designated a sample as positive if (1) at least one of the replicates generated a melt curve within ± 0.5 °C of that of L. californiae, which we identified during the primer selection phase, and (2) the cycle threshold value (Ct) of 40, set as the detection limit, coincided with that of L. californiae28,58. To reduce subjectivity in the interpretation of melt curves, two researchers evaluated the results, and only samples with clearly similar melting curves and Ct values to those of L. californiae were considered as positive (we repeated those that were ambiguous).

To minimize contamination during laboratory procedures, we handled DNA isolates and prepared qPCR reactions using filtered pipet tips and under the laminar flow hood in the pre-PCR laboratory. We performed all tasks in a dedicated working area within the pre-PCR laboratory, which was thoroughly cleaned with 10% diluted bleach after processing each sample. We used new disposable gloves to manipulate each sample and to access to the freezer, and all instruments were sterilized with 10% diluted bleach, rinsed with distilled water and dried with disposable paper towels. We carried out amplifications in a post-PCR laboratory within the CSIC facilities that did not share equipment or material with the pre-PCR laboratory. We transferred samples between pre- and post-PCR laboratories in a single direction (pre-PCR to post-PCR), and we spaced the pre-PCR and post-PRC work at least 24 h apart.

Finally, we compared detection rates obtained only from ACO swab samples among periods, sites and types of materials using Chi square tests. We used the package chisq.posthoc.test59 to retrieve standardized residuals, and obtain cell-specific p-values as a post hoc test following Beasley and Schumacher60. We performed all data analysis using R 4.4.161.

Accumulation and degradation of Lampropeltis californiae eDNA

To analyze the accumulation and degradation of L. californiae eDNA, we designed a pilot experiment under controlled conditions following Kucherenko et al.27. The experiment set-up and sample collection were performed by the staff of the public company responsible for the control program, GESPLAN S.A.. On May 7th 2023, GESPLAN S.A. personnel undertook a thorough cleaning of four glass terraria (48–78 cm × 38–60 cm × 49 cm; length × width × height) using a commercial disinfectant soap and 10% diluted bleach, after which the terraria were filled with 2 L of a commercial substrate for reptiles (Repti-Selva Sand, ICA S.A., Spain). On the subsequent day, GESPLAN S.A. staff collected a sample of substrate (negative control) filling up a 2 mL tube with a similar amount of substrate from each corner and center of each terrarium. At 7 a.m. of the same day, they placed one adult individual L. californiae in each terrarium, collecting a substrate sample every hour onwards until 5 p.m. of the same day and one sample per day in the early morning until day 7, when they removed the snakes. They continued to collect substrate samples once a day from day 8 to day 12, with a final collection on day 14, as performed by Kucherenko et al.27. All substrate sample collection were carried out with care to prevent direct contact with visible urine or feces. Potential sample contamination was minimized by using new disposable latex gloves for each sample and storing them in a − 20 °C freezer located outside the facilities where terraria were situated and where no samples of L. californiae had been previously stored. We transported all samples to the CSIC laboratory facilities for subsequent analysis.

We extracted the DNA in the CSIC laboratories using a self-designed protocol with the following steps: firstly, we transferred the contents of each sample tube into a new 2 mL tube, which we then stored at − 20 °C; secondly, we rubbed a sterile cotton swab moistened with ultrapure water (Ultra Pure Water System, Milli-Q®, Millipore®, USA) over the walls of the empty tube; thirdly, we cut the tip of the swab and dropped it into a 1.5 mL tube. This protocol reduced the time of sample processing without compromising the sensitivity of the technique (tested against other two alternative sample processing methods; see results of those other methods in Supplementary Information II). We extracted DNA from the swab tips using the commercial extraction kit E.Z.N.A.® Tissue DNA (Omega, Bio-tek Inc., USA), following the manufacturer’s protocol.

We utilized conventional PCR for the amplification of extracted DNA from samples collected during the initial phase in the terraria (days 1 to 7), whereas we employed qPCR for subsequent samples collected after snake removal. We used these two approaches due to budgetary and logistical constraints, and used qPCR to better characterize the degradation of eDNA. We performed conventional PCRs in a Bio-Rad T-100 Thermal Cycler (BioRad, Hercules, USA) using a total volume of 20 µL containing 2 µL of T10x PCR TaKaRa (15 mM MgCl2) (Takara Bio Inc., Japan), 1.6 µL of dNTP mix (Takara Bio Inc., Japan) (2.5 mM each), 0.8 µL (0.5 µg) of BSA (BioLine, UK), 0.64 µL (10 mM) of each primer, 0.125 µL of TaKaRa Taq (1.25 U/µL) and 2 µL of the extracted DNA. The PCR conditions comprised and initial step of 1 min at 95 °C, followed by 35 amplification cycles (15 s at 94 °C, 20 s at 57 °C, and 30 s at 72 °C), and a final 10 min extension at 72 °C. We visualized the amplification results with 1.7% agarose gel electrophoresis with Real-Safe (Real Biotech Corporation, Taiwan). We replicated previously specified qPCR conditions to amplify three qPCR replicates for each sample, in addition to positive and negative controls. We undertook the evaluation of DNA degradation by exploring Ct values over time, a semi-quantitative value that is inversely related to the amount of DNA in the sample62,63.

Ethical statement

All procedures were approved by the Government of the Canary Islands under permit no. AGPA/11031/2023.

Results

Design and validation of Lampropeltis californiae specific primers

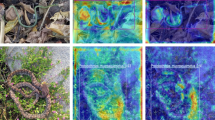

The designed primer pair (LampCOIF: 5′-TTGGGGCCTGCCTAAGTATC-3′ and LampCOIR: 5′-GGGGAAGGCTATATCGGGAG-3′) enabled the differentiation of L. californiae from other co-occurring reptiles. We confirmed the specificity of the assay through the detection of target amplicons (161 bp between primers) in agarose gel electrophoresis for L. californiae (Fig. 2A), as well as through the clear differentiation of melting curves for L. californiae and endemic reptiles (Fig. 2B). We did not observe primer dimers, reagent inhibition (all positive controls amplified), nor contamination (no negative controls amplified) during the amplifications.

Specificity of the self-designed primers for the cytochrome oxidase I subunit. Panel A shows the amplification products (≈ 161 bp) obtained from the extracted DNA of Lampropeltis californiae, Gallotia stehlini, Chalcides sexlineatus and Tarentola boettgeri and visualized through 1.7% agarose gel electrophoresis with Real-Safe (Real Biotech Corporation, Taiwan) (the third-last and last lanes represent the negative controls (-C) and the second-last lane included the 25–700 bp DNA marker (LADD-DN1-500; OXGEN™). Panel B shows the melting temperature curves obtained through qPCR when amplifying the extracted DNA from tails of the four species.

Detection of Lampropeltis californiae in environmental DNA samples

We collected a total of 290 ACO swab samples (134 during the first sampling period and 170 during the second period, with 14 samples shared between both), as well as 135 soil samples underneath the ACOs, 135 soil samples in random locations, and 39 boots’ samples (see Table 1 for details). Despite observing one active snake and several fresh skin sheds during the sampling sessions, we did not detect L. californiae individuals or physical traces under the ACOs throughout the entire sampling period. During the initial sampling period, we detected L. californiae eDNA in 8.96% of swab samples, 2.22% of soil samples collected underneath the ACOs, and 2.56% of boot samples. However, the species remained undetected in randomly collected soil and negative controls. Of the 16 samples that were positive for L. californiae during this period, 18.75% were positive in one qPCR replicate, 50.00% in two replicates, and 31.25% in all three replicates. We only detected eDNA in swabs and soil under the same ACO on the same day in one instance. Of the 12 snake detections in swab samples, 41.67% occurred in corrugated bitumen sheets, 25.00% in corrugated steel plates, 25.00% in plywood boards, and 8.33% in rubber sheets (Table 1). Sampling site 2 accounted for 75.00% of all detections, with sampling sites 1 and 3 producing 8.33% and 16.67% of all snake detections, respectively. During the second sampling period, we detected L. californiae in 9.41% of all swab samples, 25.00% of which had one positive qPCR replicate, 12.50% had two positive replicates and 62.50% had all three positive replicates. In this period, 62.50% of all detections occurred in corrugated steel plates, 25.00% in corrugated bitumen sheets, and 12.50% in plywood boards. The spatial distribution of snake detections during the second period exhibited a similarity to that of the first period, with 50.00% of all detections occurring in sampling site 2, 37.50% in sampling site 1, and 12.50% in sampling site 3.

Over the course of the two distinct sampling periods, we detected the presence of L. californiae in 9.31% of swab samples (Table 1). A 48.15% of swab positive detections were on corrugated steel plates, 33.33% on corrugated bitumen sheets, 14.82% on plywood boards, and 3.70% on rubber sheets (no detection on flat bitumen sheets). The snake detections were linked to 12 specific ACOs, seven of which detected snakes 2–5 times over the whole sampling period. A total of 62.96% of all snake detections through swabs belonged to site 2, while sites 1 and 3 produced 25.93% and 11.11% of all detections, respectively (Table 1). We did not detect positive samples in January, whereas February and March exhibited the highest percentage of positive detections (20.00% and 13.33%, respectively) (detection rate ≤ 10.00% for the remaining months).

We did not find significant differences in eDNA detection rate between periods for swab samples (\(\chi_{1}^{2}=\) 0.01, P = 1.000). However, we observed a significant variation in the detection rate among sites (\(\chi_{2}^{2}=\) 13.07, P = 0.001) and types of materials (\(\chi_{4}^{2}=\) 25.39, P < 0.001) for all periods combined. Site 2 had a substantially higher detection rate compared to the other sites (standardized residual of 3.46, P = 0.003), while site 3 demonstrated a significantly lower rate (standardized residual of -2.65, P = 0.048). Corrugated steel plates showed a higher detection rate compared to the remaining materials (standardized residual of 3.98, P < 0.001).

Accumulation and degradation of Lampropeltis californiae eDNA

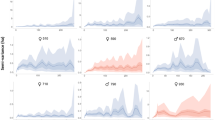

The eDNA accumulation and degradation experiment yielded a total of 92 samples (23 per terraria). We did not detect L. californiae in any terrarium prior to release of snakes (Supplementary Information III). Positive samples appeared from the first hour onwards until the snakes were removed from the terraria, yet we obtained several negative samples on intermediate days in all terraria (Supplementary Information III). The use of qPCRs led to the detection of L. californiae in all samples and terraria, with the exception of a sample collected in one terrarium on day 14. We did not detected L. californiae eDNA in any of the negative controls (Supplementary Information III). Among positive samples, 4.35% had one positive replicate, 17.39% exhibited two positive replicates, and 78.26% were positive in all three replicates. We did not detect any evidence of eDNA degradation, as Ct values from the eighth day to the end of the experiment did not progressively increase over time in any terrarium (Fig. 3).

Cycle threshold (Ct) values per each terrarium (T1–T4) in the controlled condition experiment obtained through qPCR from day 8 to 12 and day 14 (following Kucherenko et al.27), and used to analyze eDNA degradation over time after Lampropeltis californiae individuals were removed from terraria.

Discussion

Our results suggest that the primers employed for the detection of L. californiae eDNA through the COI subunit exhibited specificity and can be utilized for conservation purposes in the Canary Islands. This is evidenced by the effective amplification of L. californiae DNA, as indicated by both gel electrophoresis and qPCR evaluation, and the lack of amplification for the endemic reptiles, as well as through the discrimination of L. californiae eDNA from all sympatric reptiles using the variation in melting temperature curves. Ensuring sensitivity and specificity is a crucial step in the effective application of eDNA techniques14,64, as false positives or false negatives may lead to misguided management outcomes12. Therefore, this represents a significant initial advance in the utilization of eDNA techniques for the management of L. californiae invasion. The focus of our detection protocol on the COI subunit was driven by its high interspecific variability65 and availability of a substantial reference database for this region66. However, environmental samples can contain eDNA sequences from numerous taxa at concentrations that may exceed those of the target species13,64,67. Therefore, even in the absence of any other snakes in Gran Canaria (with the exception of the Brahminy blindsnake Virgotyphlops braminus68, which is relegated mainly to gardens) it is advisable to further validate primer specificity before implementing widespread eDNA protocols. This is of particular importance if these primers are intended for use in other geographical areas, where mismatches with other untested species could occur69. Future tasks to improve qPCR specificity and sensitivity include designing a specific probe, in addition to an assay and dilution series of the target species69. The validation of primer specificity in the future would serve to substantiate the applicability of this technique, elucidate its strengths and limitations, and inform the conclusions that can be drawn from it14,64,67. In the event that the COI subunit generates primers that lack specificity when compared with a more extensive array of taxa, the use of alternative genetic markers should be investigated70.

The diverse sampling protocols employed in this study revealed that swabbing ACOs with cotton can be an effective method for detecting L. californiae eDNA, despite the absence of snakes under ACOs throughout the entire sampling period. This detection rate is comparable to that reported by Matthias et al.30 for the elusive and native sharp-tailed snake Contia tenuis (9.30%), who also employed swabs under ACOs and detected eDNA in locations where snakes had not been recently observed. The employment of ACOs constructed from diverse materials further enhanced the detection rate, achieving 15.48% and 11.49% with corrugated steel plates and corrugated bitumen sheets, respectively, the highest rate reported for terrestrial invasive snakes. This observation suggests that certain materials may exhibit superior efficacy in retaining eDNA, given the apparent lack of a clear preference for the use of specific cover materials in reptiles71. This result emphasizes the importance of selecting appropriate materials for DNA detection19,72. Consequently, future studies should focus on enhancing the detection rates of L. californiae (and other terrestrial snakes) in the field, which could be achieved by using more effective materials and studying the environmental conditions they can provide19. The detection rate obtained for soil samples collected under the ACOs (2.22%) was marginally higher than that reported for other species under similar conditions28, yet the low prevalence of snake eDNA in these samples compromises the usefulness of this sampling technique. The success of vertebrate eDNA detection is contingent on social organization, species behavior, and species biomass73. Given that L. californiae is a fossorial species that spends the majority of its time underground, travels short distances, has small home ranges34, and shows a strong preference for areas covered by vegetation and rocks (Maestresalas et al. under review), the location of ACOs within the home range of a particular snake or in favorable microhabitats could explain the clustering of most of the detections. Alternatively, the recurrence of positive detections in the same ACO may be attributable to a low rate of eDNA degradation, a finding that aligns with the outcomes of our controlled experiment and with the duration of up to two weeks after visiting an ACO of the eDNA from the little brown skink Scincella lateralis19. However, Kucherenko et al.27 did find eDNA degradation of red cornsnakes (Pantherophis guttatus) after six days of snake removal in a controlled laboratory setting similar to ours. Nevertheless, the lack of degradation in our controlled experiment, as well as the presence of negative samples on intermediate days of the experiment, may indicate potential errors in the sample processing that should be investigated further. Despite the meticulous efforts of the GESPLAN S.A. staff in avoiding contamination during sampling, the terraria were situated within the same facilities where all control program operations were conducted. This raises the possibility of other sources of L. californiae eDNA within these facilities. Therefore, future research should employ fine eDNA detection and quantification techniques to enhance our understanding of eDNA accumulation and degradation processes. While the present research offers encouraging initial progress in enhancing L. californiae detection using eDNA and unveiling the potential of this technique for the management of other elusive and terrestrial snakes elsewhere, there is still room for improvement and the development of more effective protocols. For instance, a higher detection rate may be achieved through the utilization of alternative environmental samples, such as vegetation74, rocks or invertebrate-borne DNA (iDNA)75. Given that the majority of Gran Canaria experiences semiarid conditions with limited water availability49 and all Lampropeltis species necessitate regular access to water or humid microhabitats76, the deployment of temporary water troughs in invaded areas, mimicking ponds used to detect P. molurus bovittatus in Florida77, could also provide favorable detection rates. This approach would facilitate the implementation of the well-established laboratory protocols designed for aquatic samples45,78. It would also be worthwhile to ascertain whether the probability of detection could be improved by extending the cotton disc in the ACO-based protocol or by increasing the quantity of soil collected or the number of sample replicates analyzed29,30. A more in-depth exploration of this technique could also allow for the investigation of the correlation between eDNA detection and species abundance or biomass79,80, as their link is still poorly understood for terrestrial environments81. In the present case, while we obtained a higher number of detections at the sites where GESPLAN S.A. personnel captured the highest number of individuals, this relation cannot be reliably analyzed due to the unavailability of information on the effort made at each site33. However, this result offers encouraging perspectives on the effectiveness of these methods to estimate density or abundance, critical parameters for invasive species management2,5.

The present research has the potential to enhance the capacity to detect L. californiae, thereby facilitating the determination and monitoring of the species’ distribution on the island. At present, this information can only be deduced from opportunistic detections33,82. The generation of reliable information would pave the way for the delineation and tracking of the invasion front83, and assist in the early detection of new populations84. The establishment of cost-effective detection protocols could also help in the implementation of much-needed biosecurity protocols, which are currently absent in the Canary Islands85. From a broader perspective, this study demonstrates the potential of using eDNA techniques to detect terrestrial invasive snakes, even for highly elusive species, thus providing valuable insights that can be integrated with previous studies27,28,29,30. Given that a multitude of snake species are imported annually22 and the majority of them possess low detection probability8,26,34,86, the utilization of eDNA detection could hold considerable potential to enhance surveillance and early detection efforts for snakes, which are currently characterized by substantial time and resource demands87. Furthermore, the use of eDNA for snake detection could play a pivotal role in the long-term management of these invasive species, which currently pose a significant threat to many regions worldwide, including numerous islands23,24, and which have not been successfully eradicated88,89 or even controlled on a large scale anywhere in the world. This persistent failure underscores an urgent need to explore and adopt novel methodologies to enhance management efficacy.

Conclusion and future work

The purpose of this research was to initiate the study of the use of eDNA techniques in the detection of L. californiae, an objective that aims to guide the control given the elusive behaviour of the species. In order to achieve this, we designed and tested primers for the COI subunit, allowing a short fragment of DNA from L. californiae to be amplified, but not from the coexisting reptiles. Given the relative paucity of development in eDNA sampling protocols for terrestrial environments in comparison to the aquatic counterparts, our comparative analysis on the probability of detecting L. californiae eDNA from swab samples from ACOs made of five different materials, soil underneath ACOs, random soil, and boot swab samples, suggested that swab samples under ACOs represent the most effective sampling protocol currently available (particularly effective with corrugated steel plates and corrugated bitumen sheets). Furthermore, we demonstrated that the detection rate remains consistent irrespective of the intensification of the sampling regime or the number of ACOs. However, the detection rate might be enhanced if the sampling is conducted during the months of February and March. Additionally, we concluded that, under controlled conditions, and during the seven days after an individual L. californiae was in direct contact with the substrate, eDNA degradation does not occur.

In order to implement the use of eDNA techniques in the routine management of L. californiae, further work is needed to optimise detection protocols (including refining primer specificity or eDNA amplification protocols), sampling techniques (including further research on the type of samples to be collected in the field and their location to increase detection rate), as well as to deepen the knowledge on the species eDNA accumulation and degradation in natural environments. The future development of these techniques to infer L. californiae density could be of great use for conservation practitioners.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available at Figshare and have the following DOI number: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28202660.v1.

References

IUCN. IUCN guidelines for the prevention of biodiversity loss caused by alien invasive species (IUCN, 2000).

IUCN. guidelines for invasive species planning and management on islands. https://doi.org/10.2305/iucn.ch.2018.15.en (2018).

Simberloff, D. et al. Impacts of biological invasions: What’s what and the way forward. Trends Ecol. Evol. 28, 58–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2012.07.013 (2013).

Genovesi, P. Limits and potentialities of eradication as a tool for addressing biological invasions. In Biological invasions (ed Nentwig, W.) 385–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-36920-2_22 (Springer, 2007).

Clout, M. N. & Williams, P. A. Invasive species management: A handbook of principles and techniques. Techniques in ecology and conservation series (Oxford University Press, 2009). https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199216321.001.0001

Russell, J. C., Binnie, H. R., Oh, J., Anderson, D. P. & Samaniego-Herrera, A. Optimizing confirmation of invasive species eradication with rapid eradication assessment. J. Appl. Ecol. 54, 160–169. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12753 (2017).

Sankaran, K. V. et al. Management; challenges, opportunities and lessons learned, Chapter 5. In Thematic assessment report on invasive alien species and their control of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (eds Roy, H. E., Pauchard, A., Stoett, P.& Renard Truong, T.) (IPBES Secretariat, 2023).

Guzy, J. C. et al. Burmese pythons in Florida: A synthesis of biology, impacts, and management tools. NeoBiota 80, 1–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12753 (2023).

Amos, W., Nichols, H. J., Churchyard, T. & Brooke, M. D. L. Rat eradication comes within a whisker! A case study of a failed project from the South Pacific. R Soc. Open. Sci. 3, 160110. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.160110 (2016).

Petit, J. N., Hoddle, M. S., Grandgirard, J., Roderick, G. K. & Davies, N. Successful spread of a biocontrol agent reveals a biosecurity failure: Elucidating long distance invasion pathways for Gonatocerus ashmeadi in French Polynesia. BioControl 54, 485–495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-008-9204-7 (2009).

Gutrich, J. J., VanGelder, E. & Loope, L. Potential economic impact of introduction and spread of the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta, in Hawaii. Environ. Sci. Policy 10, 685–696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2007.03.007 (2007).

Deiner, K. et al. Environmental DNA metabarcoding: Transforming how we survey animal and plant communities. Mol. Ecol. 26, 5872–5895. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.14350 (2017).

Goldberg, C. S. et al. Critical considerations for the application of environmental DNA methods to detect aquatic species. Methods Ecol. Evol. 7, 1299–1307. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12595 (2016).

Wilcox, T. M. et al. Robust detection of rare species using environmental DNA: The importance of primer specificity. PLoS One 8, e59520. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0059520 (2013).

Comtet, T., Sandionigi, A., Viard, F. & Casiraghi, M. DNA (meta)barcoding of biological invasions: A powerful tool to elucidate invasion processes and help managing aliens. Biol. Invasions. 17, 905–922. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-015-0854-y (2015).

Thomsen, P. F. & Willerslev, E. Environmental DNA—An emerging tool in conservation for monitoring past and present biodiversity. Biol. Conserv. 183, 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.11.019 (2015).

Taberlet, P., Bonin, A., Zinger, L. & Coissac, E. Environmental DNA—For biodiversity research and monitoring (Oxford University Press, 2018).

Rishan, S. T., Kline, R. J. & Rahman, M. S. Applications of environmental DNA (eDNA) to detect subterranean and aquatic invasive species: A critical review on the challenges and limitations of eDNA metabarcoding. Environ. Adv. 12, 100370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envadv.2023.100370 (2023).

Kyle, K. E. et al. Combining surface and soil environmental DNA with artificial cover objects to improve terrestrial reptile survey detection. Conserv. Biol. 36, e13939. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13939 (2022).

Kraus, F. Alien reptiles and amphibians: A scientific compendium and analysis (Springer, 2009).

Chapple, D. G., Knegtmans, J., Kikillus, H. & Van Winkeld, D. Biosecurity of exotic reptiles and amphibians in New Zealand: Building upon Tony Whitaker’s legacy. J. R. Soc. N Z. 46, 66–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2015.1108344 (2016).

Pili, A. N., Tingley, R., van Winkel, D., Maria, L. & Chapple, D. G. The escalating global problem of accidental human-mediated transport of alien species: A case study using alien herpetofauna interceptions in New Zealand. Biol. Conserv. 278, 109860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109860 (2023).

Capinha, C. et al. Diversity, biogeography and the global flows of alien amphibians and reptiles. Divers. Distrib. 23, 1313–1322. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12617 (2017).

Kraus, F. Impacts from invasive reptiles and amphibians. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 46, 75–97. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-112414-054450 (2015).

Christy, M. T., Yackel Adams, A. A., Rodda, G. H., Savidge, J. A., & Tyrrell, C. L. Modelling detection probabilities to evaluate management and control tools for an invasive species. J. Appl. Ecol. 47, 106–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2009.01753.x (2010).

García-Díaz, P., Ross, J. V., Vall-llosera, M. & Cassey, P. Low detectability of alien reptiles can lead to biosecurity management failure: A case study from Christmas Island (Australia). NeoBiota 45, 75–92. https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.45.31009 (2019).

Kucherenko, A., Herman, J. E., Everham III, E. M. & Urakawa, H. Terrestrial snake environmental DNA accumulation and degradation dynamics and its environmental application. Herpetologica 74, 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1655/Herpetologica-D-16-00088 (2018).

Ratsch, R., Kingsbury, B. A. & Jordan, M. A. Exploration of environmental DNA (eDNA) to detect Kirtland’s snake (Clonophis kirtlandii). Animals 10, 1057. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10061057 (2020).

Katz, A. D. et al. Environmental DNA is effective in detecting the federally threatened Louisiana pinesnake (Pituophis ruthveni). Environ. DNA. 3, 409–425. https://doi.org/10.1002/edn3.126 (2021).

Matthias, L., Allison, M. J., Maslovat, C. Y., Hobbs, J. & Helbing, C. C. Improving ecological surveys for the detection of cryptic, fossorial snakes using eDNA on and under artificial cover objects. Ecol. Indic. 131, 108187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.108187 (2021).

Cabrera-Pérez, M. Á., Gallo-Barneto, R., Esteve, I., Patiño-Martínez, C. & López-Jurado, L. F. The management and control of the California kingsnake in Gran Canaria (Canary Islands): Project LIFE + Lampropeltis. Aliens: Invasive Species Bull. 32, 20–28 (2012).

GESPLAN. After-LIFE communication and conservation plan. Official report (2015).

GESPLAN. STOPCULEBRAREAL (2024). https://www.stopculebrareal.com/

Maestresalas, B., Piquet, J. C. & López-Darias, M. Spatial ecology to strengthen invasive snake management on islands. Sci. Rep. 13, 6731. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-32483-x (2023).

Piquet, J. C. The perils of an invasive snake: The California kingsnake in the Canary Islands (Universidad de La Laguna, 2022).

Piquet, J. C. & López-Darias, M. Invasive snake causes massive reduction of all endemic herpetofauna on Gran Canaria. Proc. R. Soc. B 288, 20211939. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2021.1939 (2021).

Piquet, J. C. et al. Could climate change benefit invasive snakes? Modelling the potential distribution of the California kingsnake in the Canary Islands. J. Environ. Manag. 294, 112917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112917 (2021).

Hammerson, G. A. Lampropeltis californiae. IUCN red list of threatened species. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T67662524A67662576.en (2016).

Bowles, P. Tarentola boettgeri. IUCN red list of threatened species. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2024-1.RLTS.T61574A137857741.en (2024).

Bowles, P. Chalcides sexlineatus. IUCN red list of threatened species. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2024-1.RLTS.T61487A137848983.en (2024).

Bowles, P. Gallotia stehlini. IUCN red list of threatened species. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2024-1.RLTS.T61506A137850850.en (2024).

Folmer, O., Black, M., Hoeh, W., Lutz, R. & Vrijenhoek, R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome C oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 3, 294–299 (1994).

Nagy, Z. T., Sonet, G., Glaw, F. & Vences, M. First large-scale DNA barcoding assessment of reptiles in the biodiversity hotspot of Madagascar, based on newly designed COI primers. PLoS One 7, e34506. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0034506 (2012).

Velo-Antón et al. DNA barcode reference library for the West Sahara-Sahel reptiles. Sci. Data 9, 1–8 (2022).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C. & Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1547–1549. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy096 (2018).

Beng, K. C. & Corlett, R. T. Applications of environmental DNA (eDNA) in ecology and conservation: Opportunities, challenges and prospects. Biodivers. Conserv. 29, 2089–2121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-020-01980-0 (2020).

Ye, J. et al. Primer-BLAST: A tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinform. 13, 134. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-13-134 (2012).

del Arco Aguilar, M. J. et al. Mapa de vegetación de Canarias (GRAFCAN, 2006).

AEMET. Standard climate values. (AEMET, 2024). https://www.aemet.es/es/serviciosclimaticos/datosclimatologicos/valoresclimatologicos

QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project (2024).

Sepulveda, A. J., Hutchins, P. R., Forstchen, M., Mckeefry, M. N. & Swigris, A. M. The elephant in the lab (and field): Contamination in aquatic environmental DNA studies. Front. Ecol. Evol. 8, 609973. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2020.609973 (2020).

Rees, H. C., Maddison, B. C., Middleditch, D. J., Patmore, J. R. M. & Gough, K. C. The detection of aquatic animal species using environmental DNA—A review of eDNA as a survey tool in ecology. J. Appl. Ecol. 51, 1450–1459. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12306 (2014).

Tsuji, S., Takahara, T., Doi, H., Shibata, N. & Yamanaka, H. The detection of aquatic macroorganisms using environmental DNA analysis—A review of methods for collection, extraction, and detection. Environ. DNA. 1, 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1002/edn3.21 (2019).

Mauvisseau, Q. et al. Environmental DNA as an efficient tool for detecting invasive crayfishes in freshwater ponds. Hydrobiologia 805, 163–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-017-3288-y (2018).

Wood, S. A. et al. A comparison of droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (PCR), quantitative PCR and metabarcoding for species-specific detection in environmental DNA. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 19, 1407–1419. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13055 (2019).

Allen, M. C. et al. Sampling environmental DNA from trees and soil to detect cryptic arboreal mammals. Sci. Rep. 13, 180. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-27512-8 (2023).

Dejean, T. et al. Improved detection of an alien invasive species through environmental DNA barcoding: The example of the American bullfrog Lithobates catesbeianus. J. Appl. Ecol. 49, 953–959. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2012.02171.x (2012).

Piaggio, A. J. et al. Detecting an elusive invasive species: A diagnostic PCR to detect Burmese python in Florida waters and an assessment of persistence of environmental DNA. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 14, 374–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.12180 (2014).

Ebbert, D. chisq.posthoc.test: A post hoc analysis for Pearson’s Chi-squared test for count data. R Package Version 0.1.3. https://github.com/ebbertd/chisq.posthoc.test (2025).

Beasley, T. M. & Schumacher, R. E. Multiple regression approach to analyzing contingency tables: Post hoc and planned comparison procedures. J. Exp. Educ. 64, 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.1995.9943797 (1995).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (2024).

Serrano-Cumplido, A. et al. Application of the PCR number of cycle threshold value (Ct) in COVID-19. Semergen 47, 337–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semerg.2021.05.003 (2021).

Tom, M. R. & Mina, M. J. To interpret the SARS-CoV-2 test, consider the cycle threshold value. Clin. Infect. Dis. 71, 2252–2254. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa619 (2020).

MacDonald, A. J. & Sarre, S. D. A framework for developing and validating taxon-specific primers for specimen identification from environmental DNA. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 17, 708–720. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.12618 (2017).

Ward, R. D. DNA barcode divergence among species and genera of birds and fishes. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 9, 1077–1085. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-0998.2009.02541.x (2009).

Ratnasingham, S. & Hebert, P. D. N. The barcode of life data system (http://www.barcodinglife.org). Mol. Ecol. Notes 7, 355–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01678.x (2007).

Langlois, V. S., Allison, M. J., Bergman, L. C., To, T. A. & Helbing, C. C. The need for robust qPCR-based eDNA detection assays in environmental monitoring and species inventories. Environ. DNA 3, 519–527. https://doi.org/10.1002/edn3.164 (2021).

López-Jurado, L. F., Peña, M. Á. & Mateo, J. A. La culebrilla ciega de las macetas (Ramphotyphlops braminus), una nueva especie introducida en el archipiélago Canario. Bol. Asoc. Herpetol Esp. 17, 18–20 (2006).

Pawlowski, J., Apothéloz-Perret-Gentil, L., Mächler, E. & Altermatt, F. Environmental DNA applications for biomonitoring and bioassessment in aquatic ecosystems. Guidelines. Federal Office for the Environment, Bern. Environmental Studies. no. 2010: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-187800 (2020).

Nordstrom, B., Mitchell, N., Byrne, M. & Jarman, S. A review of applications of environmental DNA for reptile conservation and management. Ecol. Evol. 12, e8995. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.8995 (2022).

Liberman, Y.-R., Ben-Ami, F. & Meiri, S. Artificial cover objects as a tool for the survey and conservation of herpetofauna. Biodivers. Conserv. 33, 1575–1590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-024-02840-x (2024).

van der Heyde, M. et al. Testing multiple substrates for terrestrial biodiversity monitoring using environmental DNA metabarcoding. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 20, 732–745. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13148 (2020).

Andersen, K. et al. Meta-barcoding of ‘dirt’ DNA from soil reflects vertebrate biodiversity. Mol. Ecol. 21, 1966–1979. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05261.x (2012).

Valentin, R. E. et al. Moving eDNA surveys onto land: Strategies for active eDNA aggregation to detect invasive forest insects. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 20, 746–755. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13151 (2020).

Massey, A. L. et al. Invertebrates for vertebrate biodiversity monitoring: Comparisons using three insect taxa as iDNA samplers. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 22, 962–977. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13525 (2022).

Raiti, P. Captive care of the common Kingsnake, Lampropeltis Getula. Bull. Association Reptilian Amphibian Veterinarians. 5, 9–10 (1995).

Mousavi-Derazmahalleh, M. et al. Rock pools as a source of environmental DNA for the detection of the threatened Pilbara olive python (Liasis olivaceus barroni). Front. Environ. Sci. 11, 1187545. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2023.1187545 (2023).

Ruppert, K. M., Kline, R. J. & Rahman, M. S. Past, present, and future perspectives of environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding: A systematic review in methods, monitoring, and applications of global eDNA. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 17, e00547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00547 (2019).

Johnsen, S. I., Strand, D. A., Rusch, J. C. & Vrålstad, T. Environmental DNA (eDNA) monitoring of noble crayfish Astacus Astacus in lentic environments offers reliable presence-absence surveillance—but fails to predict population density. Front. Environ. Sci. 8, 612253. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2020.612253 (2020).

Halstead, B. J. et al. An evaluation of the efficacy of using environmental DNA (eDNA) to detect giant gartersnakes (Thamnophis gigas). USGS Official report. https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr20171123 (2017).

Carvalho, C. S., de Oliveira, M. E., Rodriguez-Castro, K. G., Saranholi, B. H. & Galetti Jr., P. M. Efficiency of eDNA and iDNA in assessing vertebrate diversity and its abundance. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 22, 1262–1273. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13543 (2022).

GESPLAN. Informe Layman. Control de la especie invasora Lampropeltis getula californiae en la isla de Gran Canaria. (Cabildo de Gran Canaria (Área de Medio Ambiente, 2015).

Keller, A. G., Grason, E. W., McDonald, P. S., Ramón-Laca, A. & Kelly, R. P. Tracking an invasion front with environmental DNA. Ecol. Appl. 32, e2561. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.2561 (2022).

Dufresnes, C. et al. Early detection and spatial monitoring of an emerging biological invasion by population genetics and environmental DNA metabarcoding. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 1, e86. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.86 (2019).

Medina, F. M., López-Darias, M. & Piquet, J. C. Rapid responses against invasive species on islands: Lessons from the introduced barbary ground squirrel atlantoxerus Getulus in the Canary Islands. Oryx 53, 782–786. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605318000200 (2019).

Christy, M. T., Savidge, J. A., Bischof, R. & Rodda, G. H. Can temperature be used as a tool for limiting brown treesnake invasion via transportation pathways? Managing vertebrate invasive species: Proceedings of an international symposium, Fort Collins, Colorado, August 7–9, 2007, 246–256 (2007).

Yackel Adams, A. A., Lardner, B., Knox, A. J. & Reed, R. N. Inferring the absence of an incipient population during a rapid response for an invasive species. PLoS One 13, e0204302. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204302 (2018).

DIISE. Database of island invasive species eradications. http://diise.islandconservation.org/ (2021).

Spatz, D. R. et al. The global contribution of invasive vertebrate eradication as a key island restoration tool. Sci. Rep. 12, 13391. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14982-5 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to M.Á. Cabrera (Gobierno de Canarias) and R. Gallo (GESPLAN S.A.) for their support to our research. We would also like to thank J.F. Saavedra, J.M Sánchez, J.A. García and the staff of GESPLAN S.A. who participated in this study. We are indebted to M. Hernández, J.A. Pérez, T. Acosta, F. Lorenzo and M.A. González for providing laboratory materials and equipment from the Biochemistry, Microbiology, Cell Biology and Genetic Department (University of La Laguna). All of them, as well as T. Klassert (Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research), provided critical insights into this study. We would also like to thank A. Borges and the staff of Agrobiology Area of the IPNA-CSIC, as well as C. González and J. Martín (IUETSPC) for lending us some of the equipment used in this study. We sincerely appreciate the contributions of two anonymous reviewers and Dr. Charles C.Y. Xu, which led to a significant improvement of our original manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

This work has been supported by the agreement between the Government of the Canary Islands and CSIC to carry out the project “Habitat use and impacts of the California kingsnake upon native communities of Gran Canaria (Lamproimpact)”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Marta López-Darias carried out the study conception and design and Mercedes López-González substantially contributed to these tasks. All authors participated in material preparation and data collection, while Mercedes López-González performed genetic analysis. Mercedes López-González and Marta López-Darias wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript, which was prepared by Marta López-Darias. Marta López-Darias was in charge of research supervision, project administration and funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

López-González, M., Piquet, J.C., Maestresalas, B. et al. Validation of eDNA methods for managing the terrestrial invasive snake Lampropeltis californiae on the Canary Islands. Sci Rep 15, 14116 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96387-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96387-8