Abstract

Handmade cloning (HMC) presents several advantages over conventional cloning, including higher throughput, cost-efficiency, and operational simplicity. However, a comprehensive analysis comparing embryo production rates and pregnancy outcomes in cattle has yet to be conducted. This study reveals that cytoplasts produced using the micropipette method exhibited higher quality than those created with a microblade, leading to improved cleavage and blastocyst rates. The fusion of one or double cytoplast did not significantly affect the developmental potential of reconstructed embryos, although blastocysts from single cytoplasts contained slightly fewer cells. Notably, HMC demonstrated higher pregnancy rates and live calf production efficiency compared to conventional cloning. Specifically, for 41 vitrified embryos from conventional cloning, the one-month post-transfer pregnancy rate was 41.4%, resulting in 6 healthy calves (14.6%). In contrast, HMC produced one-month pregnancy rates of 71.4% for fresh and 60.0% for vitrified embryos, yielding 6 (28.5%) and 4 (26.7%) healthy calves, respectively. The optimization of HMC emphasizes the micropipette method’s potential for cattle cloning applications, including genomic selection and gene editing. Additionally, novel insights into the incompatibility issues between nuclear DNA and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in cloned embryos are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The birth of Dolly the sheep at the Roslin Institute in Edinburgh in 1997 represented a landmark achievement in biology. Dolly became the first mammal cloned from an adult cell using somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), a process now widely known as cloning1. This breakthrough demonstrated that, under the right environmental conditions, a fully differentiated adult cell could indeed be reprogrammed to support normal embryonic development—a question that had intrigued scientists for decades. This pivotal discovery opened the door to the development of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) in 2006. By introducing specific transcription factors—Oct4, Sox2, c-Myc, and Klf4—into somatic cells, researchers discovered that differentiated cells could be reprogrammed to revert to a pluripotent state2,3.

Apart from the above-mentioned theoretical importance of cloning in biological science1,2, it also provides an important advancement for livestock breeding programs, by contributing to the rapid dissemination of elite germplasm4, replication of transgenic/gene edited animals5 and gene banking of proven phenotypes6,7. Cloning methods can be classified into two types, depending on whether they require a specialized piece of laboratory equipment called a micromanipulator. The conventional cloning method, which use a micromanipulator, consist of three main procedures7,8, (1) the removal of nucleus material (maternal chromosomes) from an oocyte and production of a cytoplast (enucleated oocyte); (2) microinjection of the donor cell; (3) electrofusion of the somatic cell with a cytoplast to form an embryo.

In 1998, Peura et al., attempted two changes to simplify the procedure9. Firstly, the cumulus cells and zona pellucida of an oocyte are removed by enzymatic digestion to produce a zona-free oocyte. Secondly, the nucleus of the zona-free oocyte is manually dissected using an ultra-sharp microblade under a stereomicroscope. This simplified technique was initially referred to as zona-free cloning, and later as handmade cloning (HMC)9,10,11. Importantly, this method does not require a micromanipulator. In 2011, Nasr-Esfahani et al.12 developed a simple, fast, and cost-effective protocol that uses a fine pipette to remove the nucleus. This involves grasping the cytoplasmic extrusion of an oocyte with the pipette and then pulling it out of a microdrop of medium beneath mineral oil. The surface tension between the liquid and oil effectively cuts the oocytes into two halves. To distinguish between the different processes that have evolved based on the tools used and the actions performed, we describe these two zona-free cloning methods as follows: the microblade method, which uses a microblade to cut oocytes into two halves, and the micropipette method, which employs a fine pipette to remove the nuclear material from an oocyte.

Although the efficiency and throughput of these methods have not been directly compared, several studies have evaluated different aspects of these techniques alongside conventional cloning. The findings consistently indicate that HMC is significantly more efficient in embryo production and more cost-effective than conventional cloning13,14,15,16,17. However, a disadvantage of the microblade method, which uses double cytoplast to reconstruct one embryo, is that in species where obtaining a reasonable number of oocytes for cloning is limited, such as horses or camels, the overall production efficiency is affected6,18. Despite advancements and simplifications in cloning techniques, it remains far from being a conventional reproductive tool for livestock breeding or biomedical research.

With the advent of genomic selection (GS) and gene editing (GnEd), cloning now has many more potential applications in animal breeding programs than ever before4,5,6. Cloning a GS-tested bull calf at 1–3 months of age, with a gestation period of 9 months, can significantly reduce the generation interval, thereby increasing genetic progress. Similarly, multiplying and using superior females produced by cloning in breeding programs can lower the average age of selected parents producing offspring. In addition, although it is possible to perform GnEd directly on a zygote, typically via microinjection or electroporation19,20, cloning remains the primary method for producing GnEd livestock21,22. Various modelling studies suggest that incorporating GnEd into livestock breeding programs could contribute to the production of targeted new genotypes and new lines of seedstock animals, thereby accelerating the rate of genetic gain22.

Therefore, it is necessary to optimize various factors affecting HMC and propose new strategies to facilitate its wider application. In this study, we investigated: (1) the efficiency of microblade and microdroplet methos; (2) the developmental potential of cloned embryos from one cytoplast and double cytoplasts; (3) the efficacy of conventional cloning and HMC by comparing blastocyte rate, pregnancy rate and live birth rate.

Results

Comparison of microblade and micropipette methods for oocyte manipulation

To assess the quality of cytoplasts produced by two different methods, the protrusion pods of oocytes (Fig. 1A) induced by chemical treatment were removed using a microblade (Fig. 1B) or a micropipette (Fig. 1C). The resulting cytoplasts were then used to construct cloned embryos. In this experiment, double cytoplasts were fused with one somatic cell to create an embryo (Fig. 2D, E).

(A) Zona-free oocytes exhibiting induced protrusion cords; (B) Cytoplast generated using the microblade method; (C) Cytoplast produced via the micropipette method, exhibiting a larger size than those obtained using the microblade method; (D) Double cytoplast aligned with a somatic cell before electrofusion; (E) Mass electrofusion: five pairs of cytoplasts aligned for electrofusion. Scale bar = 100 μm.

(A) Fusion of double cytoplasts with a single somatic cell (arrowhead) using the micropipette method; (B) Fusion of a single cytoplast with a somatic cell (arrowhead) using the micropipette method; (C) Zona-intact oocytes microinjected with a somatic cell (arrowhead); (D) Day 7 blastocysts reconstructed using double cytoplasts; (E) day 7 blastocysts reconstructed using a single cytoplast; (F) day 7 blastocysts generated through conventional cloning. Scale bar = 100 μm.

As shown in Table 1, the micropipette method consistently outperformed the microblade method across most metrics. The micropipette method achieved a usable cytoplast rate of 95.9% ± 4.1, significantly higher than the 84.8% ± 5.3 of the microblade method (p < 0.05). A notable difference was observed in the time required to manipulate one oocyte, the microblade method took an average of 2.25 ± 0.41 min per oocyte, while the micropipette method was much faster, averaging 0.53 ± 0.06 min per oocyte (p < 0.05).

The fusion rate was also slightly lower for the microblade method (81.0% ± 3.6) compared to the micropipette method (94.2% ± 2.1) (p > 0.05). This discrepancy is attributed to a significantly higher percentage of cytoplasts produced by the microblade method rupturing during the fusion process compared to those produced by the micropipette method.

Although blastocyst formation, a key indicator of embryonic developmental potential, did not differ significantly between the two methods, the micropipette method resulted in a numerically higher blastocyst rate (43.8% ± 2.1) compared to the microblade method (37.3% ± 4.6) (p > 0.05). Additionally, the cell numbers in blastocysts from both groups showed no statistically significant variation (p > 0.05).

Comparison of single and two cytoplast methods for embryo reconstruction: impact on fusion, cleavage, blastocyst rates, and embryo quality

This experiment utilized the micropipette method to compare the effects of using double cytoplasts (Fig. 2A) versus single cytoplast (Fig. 2B) in the reconstruction of cloned embryos. The primary focus was on evaluating fusion rates, cleavage rates, blastocyst formation, and the subsequent cell number in the resulting blastocysts.

As shown in Table 2, the fusion rates between the two groups were comparable, with the double-cytoplast group achieving a fusion rate of 91.9 ± 8.1%, while the single cytoplast group reached a fusion rate of 92.9 ± 1.5% (p > 0.05). This indicates that both methods were equally effective in facilitating cytoplast fusion.

Cleavage rates were also similar between the two groups. The double cytoplast group resulted in a cleavage rate of 83.1 ± 3.7%, whereas the single cytoplast group produced a cleavage rate of 84.1 ± 4.1% (p > 0.05).

However, the blastocyst rates exhibited a significant difference between the groups. The single cytoplast group achieved a higher blastocyst rate of 55.3 ± 4.0% compared to 42.3 ± 5.1% for the double cytoplast group (p < 0.05). This suggests that utilizing a single cytoplast may enhance the developmental potential of embryos, leading to increased blastocyst formation.

Embryo cell number serves as an indicator of blastocyst quality. The double cytoplasts group resulted in an average cell number of 103.3 ± 33.2 (Fig. 2D), while the single cytoplast method produced embryos with a lower average cell number of 85.1 ± 30.1 (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2E). Although the single cytoplast method yielded a higher blastocyst rate, the embryos had fewer cells, which may indicate differences in developmental trajectory or overall quality.

These results indicate that both the double cytoplast and single cytoplast methods are equally effective in terms of fusion and cleavage rates. However, the single cytoplast method yielded a significantly higher blastocyst rate, suggesting enhanced developmental potential. This improvement may be due to a more favourable microenvironment for nuclear reprogramming when only a single cytoplast is used.

Comparison of pregnancy and live birth rates in conventional vs. HMC cloning methods using vitrified and fresh embryos

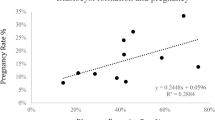

As shown in Table 3, at day 30 following embryo transfer, the HMC fresh embryos (Fig. 2E) exhibited the highest pregnancy rate at 71.4%, suggesting that fresh embryos are more effective at establishing early pregnancies. HMC vitrified embryos followed with a pregnancy rate of 60.0%, while the conventional vitrified group (Fig. 2F) had the lowest early pregnancy rate at 41.4%. By day 240, the HMC fresh group maintained the highest long-term pregnancy rate at 38.0%, followed by the HMC vitrified embryos at 33.3%. The conventional vitrified group had the lowest long-term pregnancy rate at 19.5%.

The conventional vitrified group also had the highest abortion rate at 52.9%, indicating that more than half of the pregnancies in this group ended in abortion. The HMC fresh group showed a similar abortion rate of 46.6%, while the HMC vitrified group had a lower abortion rate of 44.4%. This suggests that HMC embryos, particularly the vitrified ones, perform better in terms of pregnancy maintenance compared to conventional methods. Veterinary examinations and biopsies showed no abnormal clinical signs in any calves, including those from early births and stillbirths. Microsatellite analysis of 10 loci (Table 4) confirmed that all cloned calves were genetically identical to donor cell line.

The live birth rate was higher in the HMC methods than in conventional cloning; however, these differences were not statistically significant. The HMC vitrified embryos produced a live birth rate of 26.7%, while the HMC fresh embryos achieved a live birth rate of 28.5%. In comparison, the conventional method yielded a live birth rate of only 14.6%. Overall, the HMC techniques produced 10 healthy female calves, while the conventional method resulted in the birth of 6 healthy female calves. As of the manuscript submission date in November 2024, the cloned calves are four – six months old and in good health (Fig. 1E). Their growth, health, and reproductive performance will continue to be monitored, with results expected to be published in the future.

Discussion

The present study aimed to compare the efficiency of two key methods for HMC in cattle, microblade and micropipette techniques, and their impact on various developmental outcomes. Our results indicate that the micropipette method offers significant advantages in terms of operational efficiency, cytoplast quality, producing higher usable cytoplast, faster manipulation times, and improved fusion success compared to the microblade method. One of the key findings of the study, the single cytoplast method exhibited enhanced blastocyst rates, suggesting a better reprogramming environment for nuclear transfer. With those simplification and optimization, HMC cloning is superior to conventional methods in terms of pregnancy maintenance and live calf production.

The oocyte contains the essential proteins, mRNA, and molecular precursors needed to reprogram a somatic cell into a pluripotent state, thereby enabling embryonic development. Consequently, the volume or size of the recipient oocyte cytoplasm plays a crucial role in the developmental potential of cloned embryos, as the number of maternal factors in the cytoplasm significantly influences the successful development of reconstructed embryos. Indeed, Peura et al. reported9 that the blastocyst rate of embryos formed from double cytoplast (150% of the original oocyte volume) was significantly higher than the ones using single cytoplasts (75% of the original oocyte volume). However, Westhusin et al.23 investigated the impact of reducing oocyte volume by 50% in comparison to a 5% reduction on the developmental potential of cloned embryos, with no significant difference was observed in the blastocyst rate between the two groups, although the cell numbers in the resulting blastocysts were significantly lower when 50% of the cytoplasm was removed. In contrast to the previous two reports, the results of the present study showed that the single cytoplast group (containing 90–95% of the original oocyte volume) achieved a significantly higher blastocyst rate of 55.3%, compared to 42.3% in the double cytoplast group (containing 180–190% of the original oocyte volume). Although the single cytoplast method produced embryos with fewer cells (85.1 ± 28.1), which was not statistically different from the double cytoplast group (103.3 ± 33.2).

Accumulating evidence suggests that the presence of two or three different mtDNA genotypes (heteroplasmy) in cloned embryos may disrupt ATP production p24,25, subsequently compromising development26. The higher blastocyst rate in the single cytoplast group likely resulted from avoiding this issue, whereas the double cytoplast group exhibited fewer cleaved embryos progressing to blastocysts, possibly due to inadequate embryonic genome activation. Additionally, mtDNA copy number is critical for cell division and differentiation, as insufficient levels may lead to developmental defects or implantation failure27,28. Despite their smaller size, single cytoplast embryos achieved higher blastocyst, pregnancy, and live birth rates, suggesting that their mtDNA copy number was above the threshold for successful fertilization and development28,29.

Additionally, mitochondria in bovine oocytes are often distributed unevenly, clustering around the spindle or specific cytoplasmic regions30,31,32. As a result, the microblade method may introduce variability in mitochondrial copy number within the cytoplast, potentially affecting the developmental competence of reconstructed embryos. These findings highlight the need for further investigation. A previous study reported that the microblade method led to a significantly higher early pregnancy rate than conventional cloning, though this advantage did not translate to a higher live birth rate due to an increased abortion rate. In contrast, our results demonstrate that the micropipette method not only improved the initial pregnancy rate but also achieved a greater live birth rate compared to conventional cloning. This indicates that optimized HMC embryos have superior in vivo developmental potential compared to conventionally cloned embryos.

The significantly higher usable cytoplast and fusion rates achieved by the micropipette method demonstrate the superior quality of cytoplasts compared to the microblade method. Most notably, the size of the cytoplasts (90–95% of the original oocyte volume) allows for the reconstruction of cloned embryos using a single cytoplast, resulting in a significantly higher blastocyst rate. In agreement with our results, the rate of successful fusion in the micropipette method was greatly improved in comparison to the microblade method in camel cloning33. This offers a substantial advantage in conserving valuable oocyte resources, especially in species where oocyte availability is limited, making the use of multiple cytoplasts, as required in the microblade method, impractical. In addition, producing cytoplasts of consistent size is important to prevent lysis of couplets during mass fusion (Fig. 1E). The micropipette method not only generates cytoplasts of uniform size but also significantly increases the throughput of oocyte enucleation12,34,35. Moreover, given the limited availability and high cost (~ AUS$70) of microblade, the micropipette method offers a more cost-effective approach, using only a simple, self-made fine pipette for oocyte enucleation. In addition, Oback et al. reported no improvement in pregnancy rates at Day 35 and Day 83 from embryos generated using either single or double cytoplast via embryonic cell transfer (ECT)34,36. This finding is notable because the double cytoplast group exhibited significantly higher in vitro development. The enhancements included a doubled blastocyst rate and the production of higher-grade embryos31,32. Considering the conclusion from the experiment that double cytoplast embryonic cloning improves in vitro but not in vivo development in cattle, and our observation that single cytoplasts increased the fusion and blastocyst rates of cloned embryos, we chose to use the single cytoplast method with micropipette manipulation to compare its efficiency with conventional cloning.

A lower pregnancy rate, higher abortion rate, and the occurrence of abnormal calves are factors that limit the broader application of cloning technology in animal breeding compared to other ARTs. As a functional bioassay for SCNT, the production of viable offspring is the most definitive measure of the extensive donor cell reprogramming required, often referred to as cloning efficiency33. We directly compared these parameters between our optimized micropipette method and conventional cloning. The results indicated a higher pregnancy rate at both Day 30 and Day 240 post-transfer, as well as nearly double the live birth rate with the micropipette method (HMC vitrified: 26.7%, HMC fresh: 28.5%, Conventional: 14.6%). However, the difference was not statistically significant, likely due to the smaller sample size. Further trials are needed to draw definitive conclusions. Additionally, no significant differences were observed in abortion, early birth, or stillbirth rates.

At the same time, it is important to note that two different activation methods were used in this study. The combination of Ca ionophore A23187 and 6-dimethylaminopurine (6-DMAP) was used in the HMC experiments, while cycloheximide and cytochalasin-D were used in the conventional cloning. While Ca ionophore A23187 + 6-DMAP is generally preferred due to its superior activation efficiency, better embryo quality, and closer resemblance to physiological processes37, higher pregnancy and calving rates have also been observed in bovine using cytochalasin38. Therefore, we believe that the activation method alone does not fully account for the observed higher pregnancy and live birth rates in handmade cloning.

In summary, this study demonstrates that achieving a high live birth rate with a relatively large number of embryo transfers (approximately 40 recipients) highlights the potential of the micropipette cloning method. The efficiency observed is comparable to other assisted ARTs such as IVF and embryo transfer, reinforcing the feasibility of large-scale commercial cloning in livestock breeding programs. Moreover, the ability to clone individuals with predetermined sex and genotype at different developmental stages (foetal, newborn, mature, or aged) enhances the practical applications of this technology. This capability not only facilitates the rapid dissemination of superior genetics but also strengthens gene banking and gene editing efforts. While the findings indicate promising outcomes, further large-scale trials are necessary to confirm the reproducibility and long-term viability of this approach in commercial livestock.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

All reagents and media supplements used in this study were tissue culture grade and sourced from Sigma-Aldrich Co., unless a different supplier was specified.

Animals

Sixteen Holstein cows, aged 15–28 months, served as donors for ovum OPU, while 77 heifers, aged 15–18 months, were used as recipients for embryo transfer (ET). HMC and embryo transfer were conducted at the Embryo Production Centre of Grassland & Cattle Pty Ltd, Hohhot, Inner Mongolia, China, whereas conventional cloning embryos were produced at the Chinese Agricultural University in Beijing, China. Animal ethics approval was granted by the Chinese Agricultural University Animal Care and Use Committee. Prior to the experiment, all cows underwent clinical examinations via transrectal ultrasound to assess their reproductive tracts and ovaries. Throughout the study, the cows were housed together in outdoor pens and were provided with pellets and hay to meet their nutritional needs as mature cows, along with ad libitum access to water and mineralized salt.

All methods in this study were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Furthermore, the reporting of this study adheres to the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org) for animal research.

Establishment of fetal fibroblast cell line

A 45-day gestation Wagyu fetus (ID: 21166) was obtained from the Grassland & Cattle Breeding Farm. The fetus was surgically retrieved (Fig. 3A, B) and transported to the laboratory in Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS) with antibiotics at 37 °C. Upon arrival, the fetus was washed 2–3 times in DPBS containing antibiotics and placed in a 90 mm Petri dish. Using sterilized forceps and a scalpel, the head, limbs, and internal organs were removed. The minced tissue was filtered through a cell strainer (100 μm, Corning) in order to obtain a primary cell suspension, which were transferred to a culture flask containing DMEM, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. The culture medium was refreshed every 2–3 days. Once cells reached 80–90% confluence, they were passaged using trypsin-EDTA for further expansion (Fig. 3C). After two or three passages, the cells were collected, suspended in a freezing medium containing DPBS, 10% FBS, and 10% DMSO, and stored in liquid nitrogen. Cells were serum starved by culture in medium containing 0.5% FBS for 2 days before nuclear transfer.

Follicular stimulation, OPU and in vitro maturation

The ovarian stimulation and OPU protocol followed a similar approach to that described by Joyce et al.39. On day 0, a progesterone (P4) intravaginal device (Eazi-Breed™ CIDR®; 1.38 g P4; Zoetis Animal Health, Kalamazoo, MI, USA) was inserted, and an intramuscular injection of a GnRH analog (100 µg of synthetic gonadorelin hydrochloride; Factrel; Zoetis Animal Health, Kalamazoo, MI, USA) was administered. Follicular growth was induced by exogenous FSH (Folltropin®; Vetoquinol, Canada). On day 3, 105 IU of FSH was administered intramuscularly twice, once in the morning (7 am) and again in the afternoon (6 pm). On day 4, a single injection of 70 IU of FSH was given in the morning (7 am). The CIDR was removed on the morning of day 5. OPU was performed using a real-time B-mode ultrasound scanner (Mindray 2200; Mindray Bio-Medical Electronics, Shenzhen, China) equipped with a 5-MHz micro-convex transducer (Mindray model 65C15EAV) and connected to a follicular aspiration guide (WTA, São Paulo, Brazil) and a stainless-steel needle guide. Follicles were aspirated using a disposable 18 G hypodermic needle connected to a 50-mL conical tube via a silicon tubing system (WTA). Aspiration pressure was maintained using a vacuum pump (WTA model BV-003), with negative pressure set between 60 and 80 mmHg. Only follicles approximately 2–10 mm in diameter were aspirated. After OPU from both ovaries, the aspiration system was replaced with a new one before proceeding to the next cow.

COCs were aspirated in warm OPU medium (IVF Bioscience, UK). After OPU procedures for each animal, the COCs were allowed to settle at the bottom of the collection tube. The top aqueous layer above the pelleted aspirate was carefully removed using a pipette and transferred to a fresh tube. The dense cellular debris and tissue remnants were then searched for COCs, which were subsequently washed three times with Wash medium (IVF Bioscience, UK). COCs were graded according to the International Embryo Technology Society criteria: Grade 1 COCs have more than five layers of evenly distributed cumulus cells with uniform cytoplasm, and Grade 2 COCs have three to five layers of mostly even cumulus cells and uniform cytoplasm. A selection of 25–35 COCs was placed in a 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube containing 1 ml IVM medium (IVF Bioscience, UK) in a portable incubator (Minitube, Germany) and transported to the laboratory within 3 h. Upon arrival at the laboratory, the lid of the Eppendorf tubes was opened, and the tubes was placed in an incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) set to 38.8 °C with a 5% CO₂ atmosphere and maximal humidity for 21 h.

Cytoplast preparation

Removal of cumulus cells was performed with vertexing in 0.3 mg/mL hyaluronidase solution for 2 min. Oocytes with visible polar body and intact cytoplasm were incubated in Demecolcine (2.5 µg/mL) for 2 h, then zonae pellucidae were digested in 1.5 mg/mL pronate dissolved in holding medium (TCM199 with 4 mM bicarbonate, 18 mM Hepes, and 50 µg/mL gentamicin) supplemented with 2% FBS.

For the microblade method, procedures were performed as previously described by Vajta et al.14. Briefly, zone-free, denuded oocytes were placed in 20 µL drops of holding medium containing 20% FBS, with groups of 10 to 12 oocytes per drop. Using the extrusion cone as an orientation point, a portion of the cytoplasm containing the metaphase plate was removed with a handheld microblade (Minitube, Germany). Enucleated halves retaining at least 50% of the original cytoplasmic volume were selected for embryo reconstruction. Manipulations were carried out under a stereomicroscope (SZX16 Olympus, Japan) at 40× magnification.

For the micropipette method, procedures were performed as previously described by Moulavi et al.40. During enucleation, the tip of the handheld micropipette (inside diameter 20–30 μm) was positioned close to the cytoplasmic protrusion, allowing it to enter the pipette under a stereomicroscope. Enucleation was achieved by moving the micropipette from the enucleation droplet into the mineral oil. This technique efficiently removed nuclear material with minimal surrounding cytoplasm, producing cytoplasts approximately 90–95% of the original oocyte size.

In the initial experiments, after removing the cumulus cells from the original oocytes or producing cytoplasts using different methods, photographs were taken and the diameters measured. The volume was then calculated using the formula V = πd3/6, where d is the diameter of the oocyte or cytoplast. In subsequent experiments, the volume of the cytoplasts was estimated visually based on the initial measurements9. The useable cytoplast means that the cytoplast has a round and intact membrane, as shown in (Fig. 2), and the volume is higher than 50% of the original oocyte.

Pairing and electrofusion

Fusions were performed at 23–24 h after the start of maturation. One somatic cell was paired with double cytoplastby (Fig. 1D, E) using the sandwich method as described earlier14. To facilitate attachment, one cytoplast was briefly incubated in 1 m/mL phytohemagglutinin in holding medium without FBS, and then dropped over a somatic cell. After attachment, the pair was transferred to a fusion chamber (Model 450, 01-000209-01; BTX Corp, San Francisco, CA) fusion chamber covered with 0.3 M mannitol, 0.05 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM MgCl2, and 1 mg/mL polyvinyl alcohol (PVA). With an alternate current generated by an electrofusion machine (BLS, Budapest, Hungary), the pair was floated to one of the wires with the somatic cell far from the wire, then a second cytoplast was added to touch both the somatic cell and the first cytoplast. Fusion was induced by a single direct current pulse of 2 kV/cm for 9 µs. Triplets were then carefully removed from the chamber and incubated in the holding medium with 20% FBS for 30 min to complete the fusion. These fused reconstructed embryos were then transferred into a well of a four-well dish containing 400 ul IVC medium (IVF Bioscience, UK) covered with mineral oil and incubated oil at 38.8 C in humidified mixture of 5% CO2, 5% O2 and 90% N2. Activation was initiated 28 h after the start of maturation (approximately 4 h after the fusion). Reconstructed embryos were first incubated in 1 ml holding medium supplemented with 20% FBS, containing 2 mM Ca ionophore A23187 for 5 min at room temperature. After two subsequent washings in holding medium supplemented with 20% FBS, reconstructed embryos were incubated individually (to prevent adhering to each other) in 5 µl droplets of IVC medium containing 2 mM 6-dimethylaminopurine (6-DMAP) and covered with oil for 5 h. Embryos were then washed twice in IVC medium, and cultured individually in Well of the Wells (WOWs) in 400 ml culture medium covered with mineral oil18. Embryo culture was performed at 38.8 °C, in 5% CO2, 5% O2 and 90% N2. The cleavage and blastocyst rates per reconstructed embryo were determined under a stereomicroscope at two and seven days after reconstruction.

Grade A and B embryos were selected for vitrification using the Cryotop method with media from IVF Bioscience (UK), following the protocol provided. Additionally, some blastocysts were stained on slides in a PBS solution and 10% glycerol containing 1 mg/ml of Hoechst 33,342. A drop (20 ml) of staining solution containing 1– 3 embryos was placed in the center of a slide and a cover slip was placed over the drop and the edges were sealed. Nuclei of each blastocyst were visualized and counted under epifluorescence36.

Conventional cloning

The conventional cloning was performed at the laboratory in College of Biological Sciences, Chinese Agricultural University, Beijing, and followed the procedure as we reported previously41. Briefly, oocytes were collected from OPU and subsequently matured in IVM medium (IVF Bioscience, UK) for 18–24 h at 38.5 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO₂. Donor cells were the same cell line of fetal fibroblasts that was used in handmade cloning. Cell cycle was synchronized at the G0/G1 phase by serum starvation for 2–3 days. Following synchronization, cells were selected based on their morphology and suitability for nuclear transfer.

Enucleation was achieved by piercing the zona pellucida with a glass needle, and then the polar body and surrounding cytoplasm were pushed out. Successful enucleation was confirmed by Hoechst 33,342 staining of pushed-out karyoplasts. Donor cells were then individually transferred into the perivitelline space of enucleated recipient oocytes (Fig. 2C). Reconstructed embryos were electrically fused in a chamber filled with Zimmerman cell fusion medium37 and with two stainless steel electrodes at 24 h after the start of maturation. Cytoplast–cell complexes were manually aligned with a fine glass needle so that the contact surface between cytoplast and donor cell was parallel to the electrodes. Cell fusion was induced with two DC pulses of 2.5 kV/cm for 10 msec each at 1 s apart, delivered by a BTX2001 Electro Cell Manipulator (BTX, San Diego, CA). Activation was induced by incubation in 10 mg/ml cycloheximide and 2.5 mg/ml cytochalasin-D in IVC (IVF Bioscience, UK) medium for 1 h and cycloheximide (10 mg/ml) alone for a further 4 h. After activation, embryos were further cultured in IVC (IVF Bioscience, UK) medium for 48 h in an atmosphere of 5% O2, 5% CO2, and 90% N2. Cleaved embryos were selected and cultured in 50 µl IVC droplets (IVF Bioscience, UK), grouped in sets of 5–8, for an additional 5 days. The medium was refreshed every 2 days during the culture period.

Grade A and B embryos (Fig. 3F) were selected for vitrification using the Cryotop method with media from IVF Bioscience (UK), following the protocol provided.

Embryo transfer and pregnancy monitoring

Total embryo development to blastocyst stages was assessed on D7, and grade 1 to 2 were selected for embryo transfer. Recipient cows are synchronized by a single 10–12- day CIDR-B™ (Pharmacia Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand) treatment. Four days prior to CIDR withdrawal, each cow receives 250 mg cloprostenol (1 mL Estroplan, Parnell Laboratories Ltd., New Zealand). Following CIDR withdrawal, cows are closely monitored for signs of oestrus behaviour which normally peaks 36–48 h later. On day 7 following oestrus, a single cloned blastocyst in embryo transfer medium (IVF Bioscience, UK) was loaded per 0.25 mL straw (Cryo-Vet, France) and transferred non-surgically into the uterine lumen ipsilateral to the corpus luteum. Implantation and pregnancy rates were assessed on Day 30 and Day 240 by ultrasonography following embryo transfer.

Identification of cloned offspring

Blood samples were collected from 10 calves by HMC and 6 calves from conventional cloning at one month of age and stored in EDTA-anticoagulant tubes at -20 °C. Genomic DNA was then extracted from each calf and its corresponding donor cell line for microsatellite analysis. As previously reported by our team42, microsatellite testing was conducted on cloned calves and their donor cell lines to verify genetic identity. Ten bovine DNA microsatellite markers, labelled with FAM (Table 4 for markers: ETH3, ETH225, BM1824, BM2113, INRA023, TGLA122, TGLA126, TGLA227, TGLA53, SPS115), were used for this purpose.

PCR amplification was performed under the following conditions: an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 10 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 62–52 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. This was followed by another 25 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 52 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s, with a final extension at 72 °C for 20 min. The PCR products were analyzed using an ABI 3730xL Genetic Analyzer with GeneMarker software to determine allele counts and microsatellite genotypes.

Microsatellite markers with a Polymorphic Information Content (PIC) value above 0.5 were classified as highly informative, those between 0.25 and 0.5 as moderately polymorphic, and those below 0.25 as low polymorphic loci42,43. Higher values in allele count, heterozygosity, and PIC indicate increased effectiveness for individual animal identification43.

Statistical analysis

A Welch’s t-test was conducted for each variable to evaluate significant differences in means between the groups. For each outcome, the means and standard deviations were calculated, with comparisons made for usable cytoplast rate, enucleation efficiency, fusion rate, cleavage rate, blastocyst rate, and cell numbers. Additionally, a chi-square test was utilized to assess differences in categorical variables, including pregnancy rates, abortion rates, early birth rates, stillbirth rates, and live birth rates between the conventional and HMC cloning methods. Statistical analyses were carried out using the SPSS for Windows statistical software, with a significance level set at (p < 0.05).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Wilmut, I., Schnieke, A. E., McWhir, J., Kind, A. J. & Campbell, K. H. S. Viable offspring derived from fetal and adult mammalian cells. Nature 385, 810–813 (1997).

Takahashi, K. & Yamanaka, S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 126, 663–676 (2006).

Hamilton, B., Feng, Q., Ye, M. & Welstead, G. G. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells by reprogramming mouse embryonic fibroblasts with a four transcription factor, doxycycline inducible lentiviral transduction system. J. Vis. Exp. 33, 1447 (2010).

Yadav, P. S. et al. Evaluation of postnatal growth, hematology, telomere length and semen attributes of multiple clones and re-clone of superior Buffalo breeding bulls. Theriogenology 213, 24–33 (2024).

Mueller, M. L. & Van Eenennaam, A. L. Synergistic power of genomic selection, assisted reproductive technologies, and gene editing to drive genetic improvement of cattle. CABI Agric. Biosci. 3, 13 (2022).

Olsson, P. O. et al. Blastocyst formation, embryo transfer and breed comparison in the first reported large scale cloning of camels. Sci. Rep. 11, 14288 (2021).

Selokar, N. L. et al. Establishment of a somatic cell bank for Indian Buffalo breeds and assessing the suitability of the cryopreserved cells for somatic cell nuclear transfer. Cell. Reprogram. 20, 157–163 (2018).

Hill, J. et al. The effect of donor cell serum starvation and oocyte activation compounds on the development of somatic cell cloned embryos. Cloning Stem. Cells 1, 201–208 (1999).

Peura, T. T., Lewis, I. M. & Trounson, A. O. The effect of recipient oocyte volume on nuclear transfer in cattle. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 50, 185–191 (1998).

Peura, T. T. Improved in vitro development rates of sheep somatic nuclear transfer embryos by using a reverse-order zona-free cloning method. Cloning Stem. Cells 5, 13–24 (2003).

Du, Y. et al. Piglets born from handmade cloning, an innovative cloning method without micromanipulation. Theriogenology 68, 1104–1110 (2007).

Nasr-Esfahani, M. H. et al. Development of an optimized zona-free method of somatic cell nuclear transfer in the goat. Cell. Reprogram. 13, 157–170 (2011).

Tecirlioglu, R. T. et al. Comparison of two approaches to nuclear transfer in the bovine: Hand-made cloning with modifications and the conventional nuclear transfer technique. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 17, 573–585 (2005).

Vajta, G. et al. Production of a healthy calf by somatic cell nuclear transfer without micromanipulators and carbon dioxide incubators using the handmade cloning (HMC) and the submarine incubation system (SIS). Theriogenology 62, 1465–1472 (2004).

Oback, B. et al. Cloned cattle derived from a novel zona-free embryo reconstruction system. Cloning Stem. Cells 5, 3–12 (2003).

Lagutina, I. et al. Comparative aspects of somatic cell nuclear transfer with conventional and zona-free method in cattle, horse, pig and sheep. Theriogenology 67, 90–98 (2007).

Bousquet, D. & Blondin, P. Potential uses of cloning in breeding schemes: dairy cattle. Cloning Stem Cells 6, 190–197 (2004).

Cortez, J. V. et al. Cloned foal born from postmortem-obtained ear sample refrigerated for 5 days before fibroblast isolation and decontamination of the infected monolayer culture. Cell. Reprogram. 26, 33–36 (2024).

Owen, J. R. et al. One-step generation of a targeted knock-in calf using the CRISPR-Cas9 system in bovine zygotes. BMC Genom. 22, 1–11 (2021).

Lin, J. C. & Van Eenennaam, A. L. Electroporation-mediated genome editing of livestock zygotes. Front. Genet. 12, 648482 (2021).

Jenko, J. et al. Potential of promotion of alleles by genome editing to improve quantitative traits in livestock breeding programs. Genet. Sel. Evol. 47, 1–14 (2015).

Bastiaansen, J. W. M., Bovenhuis, H., Groenen, M. A. M., Megens, H. J. & Mulder, H. A. The impact of genome editing on the introduction of Monogenic traits in livestock. Genet. Sel. Evol. 50, 1–14 (2018).

Westhusin, M. E. et al. Reducing the amount of cytoplasm available for early embryonic development decreases the quality but not quantity of embryos produced by in vitro fertilization and nuclear transplantation. Theriogenology 46, 243–252 (1996).

Mao, J. et al. Regulation of oocyte mitochondrial DNA copy number by follicular fluid, EGF, and neuregulin 1 during in vitro maturation affects embryo development in pigs. Theriogenology 78, 877–897 (2012).

Park, J. et al. Disruption of mitochondrion-to-nucleus interaction in deceased cloned piglets. PLoS One 10, e0129378 (2015).

Barnes, F. L. & Eyestone, W. H. Early cleavage and the maternal zygotic transition in bovine embryos. Theriogenology 33, 141–152 (1990).

Barritt, J. A., Cohen, J. & Brenner, C. A. Mitochondrial DNA point mutation in human oocytes is associated with maternal age. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 1, 96–100 (2000).

Wai, T. et al. The role of mitochondrial DNA copy number in mammalian fertility. Biol. Reprod. 83, 52–62 (2010).

Santos, T. A. & Shourbagy, E. St. John, J. C. Mitochondrial content reflects oocyte variability and fertilization outcome. Fertil. Steril. 85, 584–591 (2006).

May-Panloup, P. et al. Low oocyte mitochondrial DNA content in ovarian insufficiency. Hum. Reprod. 20, 593–597 (2005).

Blocher, R. et al. Cytokine-supplemented maturation medium enhances cytoplasmic and nuclear maturation in bovine oocytes. Anim. (Basel) 14, 1837 (2024).

Babayev, E. & Seli, E. Oocyte mitochondrial function and reproduction. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 27, 175–181 (2015).

Moulavi, F. et al. Pregnancy and calving rates of cloned dromedary camels produced by conventional and handmade cloning techniques and in vitro and in vivo matured oocytes. Mol. Biotechnol. 62, 433–442 (2020).

Oback, B. & Wells, D. N. Donor cell differentiation, reprogramming, and cloning efficiency: elusive or illusive correlation? Mol. Reprod. Dev. 74, 646–654 (2007).

Hosseini, S. M. et al. Cloned sheep blastocysts derived from oocytes enucleated manually using a pulled Pasteur pipette. Cell. Reprogram. 15, 15–23 (2013).

Appleby, S. J. et al. Double cytoplast embryonic cloning improves in vitro but not in vivo development from mitotic pluripotent cells in cattle. Front. Genet. 13, 933534 (2022).

Zhang, J. Z. et al. Effect of calcium ionophore (A23187) on embryo development and its safety in PGT cycles. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 979248 (2023).

Cortez, J. V. et al. High pregnancy and calving rates with a limited number of transferred handmade cloned bovine embryos. Cell. Reprogram. 20, 4–8 (2018).

Joyce, K. et al. Seasonal environmental fluctuations alter the transcriptome dynamics of oocytes and granulosa cells in beef cows. J. Ovarian Res. 17, 201 (2024).

Moulavi, F. & Hosseini, S. M. A modified handmade cloning method for dromedary camels. Methods Mol. Biol. 2647, 283–303 (2023).

Gong, G. et al. Birth of calves expressing the enhanced green fluorescent protein after transfer of fresh or vitrified/thawed blastocysts produced by somatic cell nuclear transfer. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 69, 278–288 (2004).

Wu, X. et al. Application of microsatellite markers in pig individual identified and pork traceability. J. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 33, 624–632 (2014).

Zhao, J. et al. Microsatellite markers for animal identification and meat traceability of six beef cattle breeds in the Chinese market. Food Control 78, 469–475 (2017).

Funding

This project was funded by the Department of Science and Technology of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China, under the “Revelation and Leadership” project (Project Number: 2022JBGS0023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author Contributions: M.H., as project leader, contributed to conceptualization, coordination of experiments, and original draft preparation, including Tables and Figures; R.F. and N.N. performed microsatellite testing, data analysis, and manuscript review and editing; R.S., M.S. and X.R carried out handmade cloning; F.D. and L.L. were responsible for conventional cloning; and S.B. supervised OPU and ET procedures. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Su, R., Ding, F., Sorgog, M. et al. Optimization of handmade cloning enhances pregnancy rates and live calf production in cattle. Sci Rep 15, 15032 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96511-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96511-8