Abstract

Soft computing based expert systems have a pivotal role to play in designing standalone mobility systems such as unmanned aerial vehicles. The expert systems are designed by learning from functional data of a system, thereby framing rules without relying on apre-defined model. The use of type-2 fuzzy (fuzzy-2) controllers instead of traditional proportional-integral controllers (PICs) enhances the dynamic performance of an indirect vector controlled (IVC) induction motor (IM) in this paper. The error tracking path (ETP) of PIC is fixed for a given set of gain constants. With the use of IF–THEN rules, the Mamdani fuzzy-2 inference system (MF2IS) processes ambiguous data and produces membership functions that work on three-dimensional inputs. Thus, controller gain constants become unfixed; thereby response attains zero error rapidly with an unfixed ETP. It is well-known that changing the switching frequency of the voltage source inverter (VSI) increases switching losses for the VSI but reducing total harmonic distortion (THD) of the line current and voltage of the IM is an important trade-off. Hence, this issue is also addressed by replacing fuzzy-2 duty cycle controller (F2DCC) in place of conventional duty cycle controller. Simulation experiments are conducted using MATLAB/SIMULINK to evaluate the efficacy of IM. The experimental validation is done on a prototype using Sacrae Theologiae Magister (STM) processor for 1 horsepower IM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An ideal electric drive would cover a wide speed/torque range, be powerful, and work in any of the four corners of the speed/torque graph. Generally, AC drives have a rugged construction, high power/volume ratio, and less maintenance cost. On the other hand, a dc drive draws both active and reactive power from a single port, has a poor dynamic response as torque is a function of six state variables and rotor angle which leads to complex dynamic control. In ac drives, due to the high torque/weight ratio doubly excited permanent magnet synchronous motor (PMSM) drives have become prominent along with brush-less dc (BLDC) motor drives. In the recent past, multi-phase induction motors (MIM) drive with high fault tolerance and low space harmonics are designed to outreach the performance of PMSM and BLDC drives. However, singly excited sensor-less three phase IM has found a breakthrough in medium power ac drive applications due to their low cost unlike PMSM and BLDC drives.

Still, electric drives are facing the challenges of high response, torque accuracy, reliability, low speed operation, down-sizing, increasing efficiency and attaining high speed, etc. In the 1960s, the scalar control technique for speed control of IM which was used widely but only stator variable quantities are variable thereby no control over flux and torque resulting in poor dynamic response1. Vector control techniques are introduced to emulate characteristics of a dc motor in IMD. Good dynamic responsiveness is achieved in the regulation of the ac machine’s immediate electromagnetic torque2. Implementation of direct vector control3 is based on direct measurement or estimation of the amplitude and position of the rotor, stator, or magnetic flux linkage vector. Using conventional search coils, tapped stator windings, and hall sensors compromises the machine’s design and imposes constraints imposed by the machine’s structure and thermal demands.

Because optimal inverter switching modes allow for direct and independent control of the drive flux linkage and electromagnetic torque, direct torque control (DTC) offers greater flexibility than vector control4. Due to its adaptability as a control method for induction motor DTC applications, space vector modulation (SVM) has been the subject of much study5,6,7. When it comes to DTC of IM that incorporates 2/3/5-level VSI, the modified versions of SVM that are used are hybrid space vector modulation (HSVM) and bus clamped space vector modulation (BCSVM)8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Table 1 provides a concise summary of the literature reporting on different parametric performances. There is no feedback current control in DTC, the switching frequency can be adjusted, and torque and flux linkage estimators are needed, which are disadvantages compared to IVC17. The major literature for the techniques is described in the following section.

Field oriented control of induction motor drives

Vector control orfield-oriented control (FOC) is used for induction motor drives requiring high dynamic performance. In this method, the stator current is resolved into two components- namely direct axis and quadrature axis currents, former controlling the flux in the motor and latter controlling the electromagnetic torque produced. Operating above base speed (field weakening), rapid dynamic reaction, precision speed regulation, and a wide speed range are only a few of the benefits of field-oriented management. The reference signals for the modulation technique that drives the inverter are provided by the vector controller with voltage decoupling. Here, instantaneous electromagnetic torque of ac machine is controlled with good dynamic response.

Indirect vector control of induction motor drives

IVC has inner current loop which acts more swiftly than outer speed loop18,19. This method has lesser ripple content in stator flux and instantaneous torque than IVC uses a machine model for determining the flux linkage magnitude and position20. For applications requiring instantaneous responses, such as dynamic drives, this technique works well. Managing transients is made easy with this control approach3,21. The driver circuit is expensive and complicated, which is a drawback. The detailed methodological studies on indirect vector control are reported in22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29.

Sensor less vector control of induction motor drives

Sensor less vector control is preferred due to a low requirement of sensors when compared to direct and indirect vector control methods30.

A straightforward method for detecting and correcting the inverter error in sensor-less field-oriented control of induction motor (SFOCIM) drives has been suggested by Gianmario Pellegrino et al.31. The entire process takes only a few seconds and works for drives of any size. This SFOCIM method can calculate the instantaneous position of field angle without using the speed encoder and thereby reducing the requirement of sensor. The error accumulation leads to error in inverter’s duty cycle generation as observers are used to estimate the field angle which determines the instantaneous position of rotor flux. The solution for compensation of error is to employ advanced nonlinear controllers as observers with Kalman filters to estimate the rotor field angle position accurately.

To address the issue of resistance variation and variation of magnetizing inductance caused by rotor flux reference, Mohamed S. Zaky et al.32 suggested schemes for identifying sensor-less induction motor drives that take saturation level into account, as well as stator speed. The optimal cut-off frequency is chosen via a fuzzy controlled adaptive filter, according to a sensor-less structure developed by Jordi CatalàLópez et al.33. The fuzzy controlled adaptive filter gives feasibility to design the rules in a flexible way and enables the designer to limit errors in estimating the instantaneous position of rotor flux.

A unique design for sensor-less induction motors based on flux vector acceleration torque control was put forward by Djordje Stojic et al.34. This design integrates direct torque control with speed estimate using slip frequency evaluation. One distinctive feature of the vector control method—proposed by Koichiro Nagata et al.35 is the ability to precisely regulate the induction motor’s slip angular frequency, making it very resistant to variations in motor resistance. Online estimation of the stator and rotor resistances of induction motors for speed sensor-less indirect vector-controlled drives was introduced by BaburajKaranayil et al.36. This method makes use of artificial neural networks, with the backpropagation of the error between the rotor flux linkages based on a neural network model and a voltage model being used to adjust the weights of the neural network model for the rotor resistance estimation. A sensor-less method utilizing a full-order observer—that is, the sum of the total least-squares errors—in a neural network—has been suggested by Benjamin Blunier et al.37. This simulation of a scroll compressor has been powered using an induction motor drive that does not rely on sensors.

Direct torque control of induction motor drives

Both direct torque control and indirect vector control have been successfully used, but they have some problems: they are sensitive to changes in the parameters, errors accumulate when evaluating the definite integrals, and degradation of the steady-state and transient responses occur from drifting parameter values and excessive errors if the control time is long. Both approaches require a starting state and ongoing control for the calculation to begin. Similarly, to regular VC, DTC makes use of vector relationships; however, instead of using PWM current control, it employs a type of bang-bang action.

Controllers for design of induction motor drives

Since fuzzy logic controllers (FLCs) can generate both strong steady-state response and great dynamic performance, they have already established themselves as a prominent alternative to traditional PI controllers in closed-loop operation of variable-frequency drives38,39,40.

Various optimization techniques based on soft computing controllers have been reported in literature for PWM techniques5,41,42,43and in speed control methods for motor drives. Table 1 provides a condensed summary of the literature on neuro-fuzzy, type-1, and type-2 fuzzy controllers utilized in DTC controlled IM drives, along with their various parametric performances. Table 1 shows, however, that in the field of speed control techniques for IMD, soft computing controllers—including artificial neural networks (ANNs), neurofuzzies, type-1 and type-2 fuzzy based controllers—have been identified as the most prominent controllers. Additionally, type-2 fuzzy controllers have been found to provide better steady-state and dynamic response for IMD compared to ANN, neurofuzzy, and type-1 fuzzy controllers. It can be inferred from56,57 that fuzzy-2 controllers outperform conventional PI controllers in terms of various parameters listed in Table 1. Hence overall IM performance is improved.

Recent fuzzy control literature

Several recent studies have advanced the integration of fuzzy logic in power electronic systems and electric drives, particularly in induction motor control applications. In63, various DC-DC converter topologies including SEPIC, Landsman, and Zeta were evaluated for PV-fed induction motor drives, emphasizing the need for stable and efficient converter configurations when interfacing with intelligent fuzzy-based controllers. The role of fuzzy logic in enhancing control quality is further illustrated in64, where PID and PID-fuzzy controllers were designed for six-phase drives, showing improved transient response and better adaptability to parameter changes compared to traditional PID schemes. A comprehensive review of fuzzy-logic applications in electric drives and power electronics is presented in65, where the capabilities of fuzzy systems in handling system nonlinearities, uncertainties, and real-time adaptability are emphasized, laying the groundwork for further exploration in intelligent drive control. Extending fuzzy logic into robust nonlinear control66, proposed a fuzzy-assisted sliding mode control scheme for frequency regulation in wind-powered autonomous microgrids, achieving enhanced dynamic stability under fluctuating input conditions. A similar hybrid approach was demonstrated in67, where an adaptive fuzzy sliding mode control was developed to ensure stability in distributed electric vehicle drives, emphasizing fuzzy logic’s capability to augment robustness in high-variability applications. A more targeted application of fuzzy logic in modulation was explored in68, where both type-1 and type-2 fuzzy logic were incorporated into space vector modulation (SVM) for two-level inverter-fed induction motors, resulting in reduced harmonic distortion and improved inverter switching precision—highlighting the benefits of type-2 fuzzy logic for managing uncertainty in real-time modulation decisions. The broader applicability of fuzzy clustering in complex systems was illustrated in69, where an adaptive fuzzy c-means-based SVM was employed for earthquake damage prediction, indirectly emphasizing fuzzy logic’s ability to model imprecise data—a property that is crucial in real-time motor control. Directly addressing fuzzy-based DTC strategies70, introduced a three-level fuzzy-2 logic-based direct torque control scheme using SVPWM for induction motors, achieving reductions in torque ripple and enhancing response times compared to classical DTC methods. Similarly71, presented a dynamic modeling framework for five-phase SVPWM inverter-fed IM drives, integrating an intelligent fuzzy speed controller that demonstrated superior performance in torque accuracy and efficiency. In the context of renewable energy-driven drives72, employed a grey wolf optimization (GWO)-based fuzzy MPPT controller in a fuel-cell powered EV system, showing how fuzzy inference systems can be used to optimize energy conversion efficiency dynamically. Further improving fuzzy control performance73, applied a quantum-behaved lightning search algorithm to enhance indirect field-oriented fuzzy-PI controllers, demonstrating reduced steady-state error and better disturbance rejection in induction motor control. Fuzzy control’s effectiveness in PWM-based voltage control is also evident in74, where a fuzzy SVPWM inverter was implemented for V/f speed control, resulting in smoother voltage profiles and reduced current harmonics. Power converter control using fuzzy logic was extended in75, which introduced a beta-fuzzy logic MPPT controller integrated with a novel single-switch DC-DC converter for fuel-cell electric vehicle applications, again validating fuzzy logic’s adaptability in energy optimization scenarios. Fuzzy-based speed control was further explored in76, where an improved fuzzy DTC was implemented for a wide speed range using AI-based techniques, reinforcing the value of soft computing in high-performance motor control. In77, optimization of a fuzzy controller for predictive current control of induction machines was presented, demonstrating how tuning fuzzy parameters can enhance dynamic current tracking accuracy and stability under load changes. The integration of fuzzy logic into converter design was again highlighted in78, which introduced a hybrid fuzzy MPPT controller embedded in a transformerless, high step-up DC-DC converter, designed for efficiency under varying voltage conditions. Optimization techniques were also used in79, where a fuzzy logic speed controller for induction motors was enhanced via a backtracking search algorithm, leading to significant improvements in setpoint tracking and response linearity. Real-time experimental implementation of fuzzy logic in indirect vector-controlled IM drives was addressed in80, where a laboratory setup validated the feasibility and practical advantages of fuzzy-based controllers in reducing overshoot and improving settling times. Hybrid fuzzy control structures were examined in81, which demonstrated a dual-layer fuzzy-fuzzy space vector control scheme for AC variable-speed drives, achieving substantial ripple reduction and smoother control transitions. In82, a fuzzy controller was applied to a two-leg inverter configuration for PV grid-connected systems, managing high voltage gain with enhanced MPPT efficiency through fuzzy logic regulation. Expanding the scope to type-II fuzzy systems83, proposed an adaptive neural type-II fuzzy logic speed controller for induction motors, offering superior performance in noisy environments and highlighting the added robustness of type-II systems over type-I counterparts. In84, a five-level SVM was integrated with an improved fuzzy-2 DTC method, producing enhanced torque control and power quality, while exploiting the multilevel inverter’s granularity to complement the fuzzy controller’s decision-making. Finally85, introduced an improved DTC strategy for doubly-fed induction motors using a fuzzy logic controller, showcasing increased torque stability and reduced switching stress, and underscoring the consistent trend of fuzzy logic providing intelligent, nonlinear compensation in advanced motor control strategies.

Problem statement

A two-level inverter-fed induction motor can be better controlled with type-2 fuzzy controllers than with a traditional PI-controlled FOC in terms of both steady-state performance and dynamic response. The goal of implementing a fuzzy-2 duty cycle controller is to enhance the steady-state responsiveness by increasing dc bus utilization and, as a result, the THD profile. The real time implementation is also done with PI and type-2 fuzzy control to demonstrate improvement in terms of various operating conditions.

Contributions

Using type-2 fuzzy in simulation results improves the steady state performance in terms of RMS stator flux ripple, effective dc bus utilisation, and THD of stator currents and voltages. In real time scenario on a laboratory test bench with help of a power analyzer is used to acquire the THD results of line currents and voltages with PI and fuzzy-2 controlled FOC for IM under steady state condition.

To achieve high dynamic response, the dynamic performance the performance6,44,45 is also investigated at no load during starting, step load and speed reversal operation. The results obtained of rotor speed, current and torque along with other transient response in terms of speed dip in RPM during load application and starting time are demonstrated in simulation and real time with PI and Type-2 fuzzy controllers. In order to improve the overall performance of IM, type-2 fuzzy controllers were selected as an alternative to standard PI controllers, as is evident from the results.

The indirect vector control

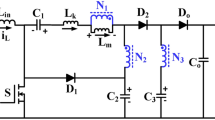

Stator flux and instantaneous torque both exhibit lower ripple content when using the IVC approach as compared to DTC46. This IVC scheme is depicted in Fig. 1, has two inner current loops which act more swiftly than outer speed loop. IVC uses a machine model for determining the flux linkage magnitude and instantaneous rotor flux position.

In IVC, an IM gives high dynamic performance in applications alike dc motor which have decoupled effect between field and armature current47,48,49. The dynamic equivalent circuit of IM is depicted in Fig. 2.

In order to create a separation between the flux and torque producing parts in a reference frame that is spinning at the same angular speed as the components, we need that to be zero and that the rotor flux in the reference frame be directed along the d-axis rotor flux, or the net resultant flux.

From the dynamic equivalent circuit of Fig. 2, Eq. (1)–(6) can be derived from50.

Assume machine is operating at constant flux (\({{\lambda_{dr}^{{}} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\lambda_{dr}^{{}} } {L_{m} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {L_{m} }} = i_{mr}\),)where \(i_{mr}\) is the magnetizing component of stator current and \(\omega_{sl}\) is slip speed in radians/second.

Here \(\tau_{r}\) is the ratio of rotor inductance \(L_{r}\) to stator resistance \(R_{r}\), \(L_{m}\) is mutually coupled inductance, \(L_{ss} = L_{s} + L_{m}\) is stator equivalent inductance, \(L_{rr} = L_{r} + L_{m}\) is rotor equivalent inductance, \(C = 1 - \frac{{L_{m}^{2} }}{{L_{ss} L_{rr} }}\) is coefficient of coupling \(i_{qs}^{e}\) and \(i_{qs}^{e}\) are dc quantities of q-axis stator current and d-axis stator current in synchronously rotating reference frame at speed of \(\omega_{s}\) under dynamic condition.

Both the electromagnetic torque and the rotor flux linkage are under the control of the decoupled. The reference currents of the \(q - d - 0\) axis (\(i_{qs}^{e*}\),\(i_{ds}^{e*}\)) are transformed into the reference phase voltages (\(v_{qs}^{e}\),\(v_{ds}^{e}\)) to be reflected as reference voltages for the control loop. The time integration of \(\omega_{sl}\) leads to calculation of rotor angle \(\theta_{r} (k)\). The value of \(\theta_{re} (k)\) is obtained by using the speed integrator block in the control loop.

The output of the PI controller can be expressed as

It is possible to describe the rate of change of torque as a function of the speed controller inputs, error speed at the kth sample (\(e\omega_{r}\)(k)), and change in error speed at the kth sample (Δ \(e\omega_{r}\)(k)).

where \(e\omega_{r} (k - 1)\) and \(e\omega_{r} (k)\) are previous and present error speeds, respectively.

The fuzzy-2 controller

Conventional PICs are sensitive to parameter variations which results in poor response of IM whenever the plant is subjected to perturbation. Also, in PICs two tuning parameters interact with each other and their influence must be balanced by the designer. Expert system design using artificial neural network, fuzzy logic and fuzzy-2 controllers, primarily in DTC and vector control techniques are addressed in the literature for improving dynamic response during starting, load change and speed reversal operation of IMType-2 Fuzzy system.

The uncertainties in the parameters are handled well with basic type-1(T1) fuzzy logic system. However, linguistic uncertainties in the membership functions cannot be modeled with T1fuzzy sets. The uncertainty in membership functions (MFs) is incorporated in type-2 (T2) fuzzy set system51,52.Eventually, T2 fuzzy MFs enable us to quantify even noisy measurements. In view of computational simplicity, interval type-2 (IT2) fuzzy MFs are preferable over the general type-2 (GT2) MFs. Figure 3 shows the block diagram of a Type-2 fuzzy system, which helps to explain the different steps53.

To begin the firing of rules at the rule base layer, the fuzzification procedure is used, which involves replacing the entire antecedent component with the membership degree. Assuming a Gaussian membership function is applied to achieve a type-2 fuzzy number, the crisp number would be fuzzified in two steps to handle the AND operation in the antecedent section of a Mamdani fuzzy-2 inference system (M2FIS).

where \(\overline{\mu }_{{_{{\tilde{I}}} }}\) is primary membership degree, m is Mean and σ is standard deviation of Gaussian curve

where \(\underline{\mu }_{{_{{\tilde{I}}} }} (i)\) is secondary degree and \(\rho \, \in \, [0, \, 1]\) is the domain of secondary membership function for each \(i\).Then aggregation operation of which works on the backdrop of rule base is initiated.

The design of rule base for F2MIS requires expert knowledge of variations in error and change in error of the overall function of the system in which it is deployed. In type-2 FLS having \(p\) inputs,\({i}_{1}\in {I}_{1},{i}_{2}\in {I}_{2},\dots {i}_{p}\in {I}_{p}\) and one output \(o\in O\), m rules,\({r}^{th}\) rule has a form.

\({R}^{r}\): IF \({i}_{1}\) is \({\widetilde{I}}_{1}^{r}\) and \({i}_{2}is{\widetilde{I}}_{2}^{r}..\)… and \({i}_{p}\) is \({\widetilde{I}}_{p}^{r}\) THEN \(o\) is \({\widetilde{O}}^{r}\)

The output type-2 fuzzy set \({r}^{th}\) for rule is in (12)

where, \({\overline{f}}^{r}={\overline{\mu }}_{\widetilde{{{I}_{1}}^{r}}}\left({i}_{1}\right)*{\overline{\mu }}_{\widetilde{{{I}_{2}}^{r}}}\left({i}_{2}\right)\) and \({\underline{f}}^{r}={\underset{\_}{\mu }}_{\widetilde{{{I}_{1}}^{r}}}\left({i}_{1}\right)*{\underset{\_}{\mu }}_{\widetilde{{{I}_{2}}^{r}}}\left({i}_{2}\right)\), * is product t-norm operation. \({\overline{\mu }}_{\widetilde{I}}\) and \({\underset{\_}{\mu }}_{\widetilde{I}}\) are grades of upper membership function and lower membership function, respectively.

Type reduction follows the aggregation procedure. The center-of-sets (COS) type-reduction method uses the left and right endpoints of the type-reduced set, which is an interval type-1 set, as its scalar outputs. The procedure for doing type reduction on the center of sets in a general type-2 fuzzy logic system is as described in (16)where \({C}^{r}\) centroid of ith consequent set is

where \({d}_{i}\in {C}_{r}={C}_{{\widetilde{I}}_{1}^{r}}\) The lower membership point (LMP) and upper membership point (UMP) are obtained in (15) & (1). The type of reduction Karnik–Mendel type reduction algorithm is followed to obtain type-1 output fuzzy set.

For l = 1,…,m, the degree of firing associated with the rth subsequent set is the centroid of that set, which yields crisp output.

Design of fuzzy-2 speed and current controllers

Figure 4a shows the development of an IM’s IVC utilizing a speed controller based on the Mamdani fuzzy-2 inference system (M2FIS), which replaces PIC. The M2FIS has two input variables,\(e\omega_{r} (k)\) and \(\Delta e\omega_{r} (k)\).After passing these input signals via an M2FIS, which helps to achieve a steady-state error of zero in monitoring the reference speed signal, they are compared with the set reference speed and the error speed, as shown in Eqs. (9)–(10). The corresponding rules relating to the input and output parameters are indicated in Table 2. The input and output parameters are represented in type2 fuzzy environment with 9 MFsare shown in Fig. 4b.

In order to function properly, the IVC requires two separate current controllers, one for the q-axis and one for the d-axis. A speed controller is a good example of how all current controllers are structured. Two input variables to the current controller are reference current and change in current. Reference current is the output of the speed controller. The present controller’s fuzzy rule base is detailed in Table 3. The synthesis of output is depicted in Fig. 5a. The fuzzified parametric representation with 5 MFs is shown in Fig. 5b.

The inner current loop for d-q axis current controllers is designed first for a step reference input command as presented in Fig. 5c.

Proposed fuzzy-2 duty cycle controller for HSVM

Hybrid space vector modulation (HSVM)

For an IM, PWM used in IVC comprehends its steady state performance31,32,54,55. Generally, at constant dc bus voltage (\({V}_{dc}\)) to have optimum dc bus utilization, PIC control gains are tuned for IVC method such that, the M is high (M > 0.8) during starting and speed reversal, medium (0.6 < M < 0.8) when load is applied and low (M < 0.6) at no-load condition. Since different PWM methods give optimum performance at different M values, the HSVM33,34 method is preferred choice which is a combination of three pulse-width modulation schemes. In HSVM, PWM switching states (0127), (0121) and (7212) in sector1 are selected based on M and phase angle of reference voltage as described in Fig. 6.

The steady-state performance of IM is improved under all operating situations by using this HSVM33,34,35 approach, which minimises ripples in RMS stator flux, torque, stator current, and total harmonic distortion (THD) of line voltage at low, medium, and high M14,36,37,56,57,58,59,60,61,62.

From the Clarke’s transformation the reference phase voltage vector (V RPV) is expressed as

By applying volt-second balancing principle dwell times T1, T2 and TZ are obtained. Further, the duty ratios dt1, dt2 and dt0are expressed as independent of sampling time Ts(= 2TZ)

where

The instantaneous average phase voltage vector is for all sectors is contextualized and the sector wise three phase average phase voltage vectors in the form of a Table 4 expressed in terms of dwell time duty ratios.

Using the dwell time duty ratios found in Table 4, the hybrid switching sequence in sector 1 is generated as (0127), (0121) and (7212) in zones X, Y, and Z, respectively. These gate pulses are applied to phases a, b, and c. This HSVM requires single switching of one phase with a sampling time (TS), double switching of one phase with sampling time (TS/2) and clamping the other phase to either 0 or 1.

Design of fuzzy-2 duty cycle controller (F2DCC)

Enclosure in the performance of Inverter as well as IM is achieved by incorporating F2DCC. The improvements viz. enhanced dc bus utilization, reduced RMS stator flux ripple, and reduced response time.

The HSVM necessities two proposed F2DCCs to generate three dwell time duty ratios, viz. D1, D2 and D0. The two inputs to each of the F2DCC are sector angle α \(\left(k\right)\) and change in sector angle \(\Delta \alpha \left(k\right)\) are given by

The fuzzy rule base for the duty cycle controllers D1 and D2 are listed in Tables 5 and 6 respectively. The synthesis of outputs is depicted in Fig. 7a. The fuzzified parametric representation with 5 MFs is shown in Fig. 7b and c.

The crisp outputs D1 and D2 of the proposed F2DCC is further processed by multiplying with VRPV to acquire dwell time duty ratios dt1, dt2 and dt0. These are applied as per HSVM switching Table 7 and compared with carrier wave of switching frequency (1/Ts), to generate gate pulses Sa, Sb and Scfor three phase inverters.

The complete block diagram in Fig. 8 depicts the IVC of IM incorporating the simplified fuzzy-2 controller blocks for speed, currents and dwell time duty cycles.

Simulation studies

For simulation atudy MATLAB/SIMULINK Ver. 8.2 and Fuzzy2 Toolbox Ver. 1.0 for the simulation and the analysis of the results. The Appendix (Supplementary Material) contains the parameters that were utilized in simulation studies. The implementation in terms of software filters which are essential for reducing ripple content in the d and q axis currents is taken care by using simulation filters (software filters). In the control strategy employed two exponential filters are used for filtering out ripple content.

Performance in both dynamic and stable states is assessed here. Time for settling, perturbation of speed, and torque ripples are all components of dynamic performance. The time spent to attain reference IM speed 1450 rpm at no-load condition from starting is taken as settling time. The less settling time resembles the quick response. The speed perturbation represents the sudden dip and rise in the speed of IM during load transitions from no-load to under loaded condition and vice versa. The Torque ripples are mainly due to flux and currents. The steady state performance involves RMS stator flux ripple, %THD in line currents, DC bus utilization and operating range of IM.

Response of IM with PI controllers fed IVC using HSVM

The IVC scheme implemented with PI controllers for speed and currents, and HSVM shown in Fig. 1 is built in SIMULINK. The loaded condition is set with a torque of 1.5 Nm from t = 1 s to t = 1.5 s. The dynamic performance is evaluated from the simulation responses shown in Fig. 9. The settling time of 0.6sand speed perturbation of 6 rpm as per Fig. 9a. The considerable torque ripples are seen present from Fig. 9b. The IM draws inrush stator current at starting till it reaches the reference rotor speed, later it settles down at no-load current of 1Aand its variation under loaded condition is as in Fig. 9c.

Response of IM with proposed fuzzy-2 controllers fed IVC using HSVM

The IVC scheme implemented with Fuzzy-2 controllers for speed and currents, and proposed F2DCC HSVM shown in Fig. 8 is built in SIMULINK. The load transition instants kept the same as in previous case. The improved simulation response waveforms are presented in Fig. 10. It is evident from Fig. 10a, the settling time is reduced to 0.46 s and speed perturbations are also reduced to 3 rpm. The torque ripples are drastically minimized as shown in Fig. 10c, which indicates smooth operation of IM during load transitions.

Comparative analysis

At a given instant of time, in a sub cycle interval TZ, error exists between applied voltage vectors in Eq. (23) and VRPV. Stator flux ripple is the outcome of the time integral of the aforementioned mistake. To determine the RMS stator flux ripple for each of the three switching sequences, we use formulas from15. An optimisation of the stator flux ripple with respect to the switching sequences in each zone within a given sector yields the envelop. This envelop for HSVM is presented in Fig. 11. It is observed that inclusion of proposed F2DCC controller for HSVM improves steady state performance of IM i.e., reduction in RMS stator flux ripple. The flux ripple band is 14 mWb in SVM and 4 mWb in T2MFLC. Thus, the ripple band in latter case is reduced to less than 30% of conventional SVM for the same value of modulation index.

Efficiency of drive at DC voltage of 400 V, load torque of 2 Nm and modulation indices of 0.82 and 0.866 is calculated. The efficiency is found to have increased by more than 3% and 8% for these two modulation indices. Higher modulation indices above 0.82 give higher efficiencies because of effective dc bus utilization.

Trajectory of average potential is also improved using proposed controller in HSVM as shown in Fig. 12 for a specified Vdc and M, which is a measure of effective utilization of DC bus voltage. The 2-level inverter produces 3-levels in line voltage. Figure 13a shows the inverter’s simulated waveforms for line voltage and line current. Figure 13b and c show the frequency spectra of the inverter’s line current with the PI controller and the suggested Fuzzy-2 controllers, respectively. It indicates harmonic content of considerable magnitude seen present in low frequency region of Fig. 13b. The % THD of 4.25 with PI controllers is reduced to 2.79 by deploying proposed controllers. The improvement in DC bus utilization is observed through reference space vector trajectory as the average voltage vector value is more by a fair margin of 8.5% as illustrated in Fig. 12. Table 8 depicts the average instantaneous values in each sector of 600 for different controllers.

The Speed-Torque characteristics of IM in four-quadrant operation are for both the cases of PI controller and proposed controllers are presented in Fig. 14. The IM emulates the separately excited DC motor characteristics. The transition from motoring to braking or from forward motoring to reverse motoring is smoother with former controller compared with latter controller, whereas it produces violent fluctuations during baking period. Also, for an operating region of + 3 Nm to − 3 Nm, it operates at constant speed of 1450 rpm from 1st quadrant to 2nd quadrant and transits to 3rd quadrant smoothly to − 1450 rpm. However, for the same torque range, the range of speed changes to + 1385 to − 1385 rpm with PI controller. If higher range of speed operation is required, the torque range is to be decreased to + 2 Nm to − 2 Nm. Thus, speed-torque operating range can be widened with fuzzy-2 controller. Similarly, transitions with opposite signs of speed and torque can be interpreted from reverse motoring to forward motoring through reverse braking. Also starting torque with this controller is more than twice the starting torque with PI controller.

This shows that operating range is increased in all four quadrants, which enhances the scope of electric drive applications.

Experimental validation

To validate the simulation results discussed in section "Simulation studies" experimentation is done. Figure 15a shows various components of experimental setup and their interconnections. The laboratory test bench is developed as depicted in Fig. 15b. The parameters and specifications for experimental studies as presented in Appendix (Supplementary Material).

A diode bridge rectifier is used to obtain the DC bus voltage from a 415 V three phase supply. Two DC link capacitors of 3300 uF, 400 V are connected in series to provide 600 V DC supply to the inverter. The power inverter (Fairchild) FNA22152 is built with IGBTs of 1200 V, 25A and gate drive arrangement. Three current sensors (LEM LTS-25 NP), a voltage sensor (AD202KY) and an encoder are used to provide feedback signals for closed loop operation. The digital controller design is enabled by STM32F79I ARM cortex M4 micro controller. A DSP with specialized hardware for signal processing and matrix calculations effectively is employed for managing the challenges of high sampling rates and switching speeds. The gated pulses from micro controller are connected to power inverter through opto-isolator 6N137. A YOKOGOWA WT-330digital power analyzer is used for recording experimental waveforms. The sensors and their calibration details are discussed in Appendix. For our bench tests these conditions were deliberately chosen to rigorously evaluate the robustness and performance of the proposed control strategy under demanding operating circumstances as shown in Fig. 16 to plot efficiency at two loads for different modulation indices.

Response of IM with PI controllers fed IVC using HSVM

Figure 17 displays the experimental outcomes of IM using PI controllers. According to Fig. 17a, the settling time to attain the reference rotor speed of 1450 rpm is 3.5 s. @ no-load. The load transitions are presented in Fig. 17b, indicating the speed and current variations during different operating conditions. The speed perturbations of 6.5 rpm and torque ripples are observed from Fig. 17c.

Response of IM with proposed fuzzy-2 controllers fed IVC using HSVM

The improved experimental results of IM with Proposed Fuzzy-2 controllers are presented in the Fig. 18. The settling is seen reduced to 3 s in Fig. 18a. During the load transitions a Fig. 18b, shows the speed and current variations during different operating conditions. The speed perturbations are seen reduce to 2.5 rpm and reduced ripple content in the torque under loaded condition as shown in Fig. 18c.

Comparative analysis

Figure 19a displays the inverter’s experimental findings for line voltage and line current. See Fig. 19b for the frequency spectra of the inverter’s line current with the PI controller and Fig. 19c for the suggested Fuzzy-2 controllers. It indicates harmonic. Content of considerable magnitude seen present in low frequency region of Fig. 18b. The % THD of 5.094 with PI controllers is reduced to 4.658 by deploying proposed controller.

Conclusion

This study shown that a two-level inverter-fed induction motor drive can benefit from using Type-2 fuzzy logic controllers (FLCs) for indirect vector control (IVC). By swapping out the old proportional-integral controllers (PICs) for Mamdani fuzzy-2 inference systems (MF2IS), we hoped to improve the system’s dynamic and steady-state performance. The proposed approach dynamically adjusts controller gain constants, leading to rapid error minimization, improved stability, and greater robustness in handling parameter variations and uncertainties.

A significant contribution of this study was the integration of a fuzzy-2 duty cycle controller (F2DCC) within the hybrid space vector modulation (HSVM) scheme. With this adjustment, the voltage source inverter was able to reduce total harmonic distortion (THD) while minimising switching losses. The system’s overall efficiency was enhanced thanks to the improved duty cycle regulation, which allowed for more effective utilisation of the DC bus voltage. The proposed FLC-based HSVM strategy effectively reduced stator flux ripple and torque pulsations while ensuring smoother speed transitions under varying load conditions.

The performance evaluation was carried out through extensive MATLAB/SIMULINK simulations and validated through experimental testing on a prototype setup using an STM-based processor and a 1 HP induction motor. The results demonstrated that the fuzzy-2 controlled IVC system achieved:

-

Faster response times and reduced settling times compared to conventional PIC-based control.

-

Significant reduction in torque ripple, ensuring smooth motor operation.

-

Better control of speed, especially in short-lived situations like step load and reversed speed.

-

Lower THD in line current and voltage, contributing to better power quality.

-

Enhanced DC bus voltage utilization, leading to higher efficiency.

In both dynamic and steady-state operations, the experimental validation proved that the suggested fuzzy-2 controller beats traditional PI controllers, establishing its viability as a solution for high-performance motor drive applications. The system successfully dealt with external disturbances and nonlinearities—common problems in industrial motor drives—by utilising the adaptability of Type-2 fuzzy logic.

Hybrid optimisation methods, which combine fuzzy logic with artificial neural networks or evolutionary algorithms, can be explored in future study to further optimise controller performance, expanding this research. To further understand the approach’s scalability and practicality, it would be beneficial to test it in real-time on industrial drives with larger power outputs and see how various modulation schemes affect system performance.

This study reinforces the potential of soft computing-based expert systems in modern motor drive applications, paving the way for more intelligent, efficient, and adaptive control strategies in industrial automation.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Alfredo, M. G., Lipo, T. A. & Novotny, D. W. A new induction motor V/f Control method capable of high-performance regulation at low speeds. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 34(4), 813–821 (1998).

Venkataramana, N. & Singh, S. P. A comparative study of V/f-controlled IM using two and three level bus clamped SVM. In 2014 IEEE 6th India International Conference on Power Electronics (IICPE) 1–6 (IEEE, 2014).

Uddin, M. N., Radwan, T. S. & Azizur Rahman, M. Performances of fuzzy logic-based indirect vector control for induction motor drive. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 38(5), 1219–1225 (2002).

Matsuo, T., Blasko, V., Moreira, J. C. & Lipo, T. A. Field oriented control of induction machines employing rotor end ring current detection. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 9(6), 638–645 (1994).

Bose, B. K., Patel, N. R. & Rajashekara, K. A neuro-fuzzy-based on-line efficiency optimization control of a stator flux-oriented direct vector-controlled induction motor drive. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 44(2), 270–273 (1997).

Habetler, T. G., Profumo, F., Pastorelli, M. & Tolbert, L. M. Direct torque control of induction machines using space vector modulation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 28(5), 1045–1050 (1992).

Busireddy, H. K. et al. A modified space vector PWM approach for nine-level cascaded H-bridge inverter. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 44, 2131–2149 (2019).

Kumar, B. H. et al. An improved space vector pulse width modulation for nine-level asymmetric cascaded H-bridge three-phase inverter. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 44, 2453–2465 (2019).

Venkataramana Naik, N. & Singh, S. P. A comparative analytical performance of F2DTC and PIDTC of induction motor using DSPACE-1104. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 62(12), 7350–7359 (2015).

Naik, N. V., Panda, A. & Singh, S. P. A three-level fuzzy-2 DTC of induction motor drive using SVPWM. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 63(3), 1467–1479 (2015).

Naik, N. V., Thankachan, J. & Singh, S. P. A neuro-fuzzy direct torque control using bus-clamped space vector modulation. IETE Tech. Rev. 33(2), 205–217 (2016).

Ramesh, T., Panda, A. K. & Kumar, S. S. Type-2 fuzzy logic control based MRAS speed estimator for speed sensorless direct torque and flux control of an induction motor drive. ISA Trans. 57, 262–275 (2015).

Ramesh, T., Panda, A. K. & Kumar, S. S. MRAS speed estimator based on type-1 and type-2 fuzzy logic controller for the speed sensorless DTFC-SVPWM of an induction motor drive. J. Power Electron. 15(3), 730–740 (2015).

Panda, A. K., Ramesh, T. & Kumar, S. S. Rotor-flux-based MRAS speed estimator for DTFC-SVM of a speed sensorless induction motor drive using Type-1 and Type-2 fuzzy logic controllers over a wide speed range. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 26(9), 1863–1881 (2016).

Singh, S. P. & Panda, A. K. An interval type-2 fuzzy-based DTC of IMD using hybrid duty ratio control. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 35(8), 8443–8451 (2020).

Singh, S. P. A novel interval Type-2 fuzzy-based direct torque control of induction motor drive using five-level diode-clamped inverter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 68(1), 149–159 (2020).

Venkataramana Naik, N. & Singh, S. P. Improved torque and flux performance of type-2 fuzzy-based direct torque control induction motor using space vector pulse-width modulation. Electr. Power Comp. Syst. 42(6), 658–669 (2014).

Karanayil, B., Rahman, M. F. & Grantham, C. PI and fuzzy estimators for on-line tracking of rotor resistance of indirect vector controlled induction motor drive. In IEEE International Electric Machines and Drives Conference 820–825 (2001).

Blaschke, F. The principle of field orientation as applied to the new transvector closed-loop control system for rotating field machines. Siemens Rev. 34(5), 217–220 (1972).

Talib, H. H. N., Zulkifilie, I., Nasrudin, A. R. & Hasim, A. S. A. Comparison analysis of indirect FOC induction motor drive using PI, anti-windup and pre filter schemes. Int. J. Power Electron. Drive Syst. 5(2), 219–227 (2014).

Abhiram, T. & Prasad, P. V. N. Type-2 fuzzy logic based controllers for indirect vector controlled SVPWM based two-level inverter fed induction motor drive. In 2014 IEEE 6th India International Conference on Power Electronics (IICPE) 1–6 (IEEE, 2014).

Karnik, N. N., Mendel, J. M. & Liang, Q. Type-2 fuzzy logic systems. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 7, 643–658 (1999).

Mendel, J. M. & John, R. I. B. Type-2 fuzzy sets made simple. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 10(2), 117–227 (2002).

Hamza, M. & YAP, Hwa Jen & Choudhury, Imtiaz.,. Advances on the use of meta-heuristic algorithms to optimize type-2 fuzzy logic systems for prediction, classification, clustering and pattern recognition. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. 13(96–109), 2016 (2016).

Sukumar, D., Jithendranath, J. & Saranu, S. Three-level inverter-fed induction motor drive performance improvement with neuro-fuzzy space vector modulation. Electr. Power Comp. Syst. 42(15), 1633–1646 (2014).

Durgasukumar, G., Abhiram, T. & Pathak, M. K. TYPE-2 fuzzy based SVM for two-level inverter fed induction motor drive. In 2012 IEEE 5th India International Conference on Power Electronics (IICPE), Delhi 1–6 (2012).

Pinto, J. O. P. et al. A neural-network-based space-vector PWM controller for voltage-fed inverter induction motor drive. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 36(6), 1628–1636 (2000).

Mondal, S. K., Pinto, J. O. P. & Bose, B. K. A neuralnetwork- based space-vector PWM controller for a three-level voltage fed inverter induction motor drive. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 38(3), 660–669 (2002).

Tripathi, A. & Narayanan, G. Investigations on optimal pulsewidth modulation to minimize total harmonic distortion in the line current. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 53, 212 (2016).

Bhavsar, T. & Narayanan, G. Harmonic analysis of advanced bus-clamping PWM techniques. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 24(10), 2347–2352 (2009).

Pellegrino, G., Guglielmi, P., Armando, E. & Bojoi, R. Self-commissioning algorithm for inverter nonlinearity compensation in sensorlrss induction motor drives. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 46(4), 1416–1424 (2010).

Zaky, M. S., Khater, M. M., Shokralla, S. S. & Yasin, H. A. Wide-speed-range estimation with online parameter identification schemes of sensorless induction motor drives. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 56(5), 1699–1707 (2009).

CatalaiLopez, J., Romeral, L., Arias, A. & Aldab, E. Novel fuzzy adaptive sensorless induction motor drive. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 53(4), 1170–1178 (2006).

Stojic, D. & Vukosavic, S. Sensorless induction motor drive based on flux acceleration torque control. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 54(3), 1796–1800 (2007).

Nagata, K., Okuyama, T., Nemoto, H. & Katayama, T. A simple robust voltage control of high power sensorless induction motor drives with high start torque demand. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 44(2), 604–611 (2008).

Karanayil, B., Rahman, M. F. & Grantham, C. Online stator and rotor resistance estimation scheme using artificial neural networks for vector controlled speed sensorless induction motor drive. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 54(1), 167–176 (2007).

Blunier, B., Pucci, M., Cirrincione, G., Cirrincione, M. & Miraoui, A. A scroll compressor with a high-performance sensorless induction motor drive for the air management of a PEMFC system for automotive applications. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 57(6), 3414–3427 (2008).

Barkati, S., Berkouk, E. M. & Boucherit, M. S. Application of type-2 fuzzy logic controller to an induction motor drive with seven-level diode-clamped inverter and controlled infeed. Electr. Eng. 90(5), 347–359 (2008).

Bhavsar, L. T. & Narayanan, G. Harmonic analysis of advanced bus-clamping PWM techniques. IEEE Trans. Power Electr. 24(10), 2347–2352 (2009).

Suresh, K. et al. Design and implementation of universal converter using ANN controller. Sci. Rep. 15, 3501. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83318-2 (2025).

Krishnakumar, V., Anbarasan, P., Venmathi, M. & Pradeep, J. Recent challenges and reviews on sensorless, PWM techniques and controller possibilities of permanent magnet motors for electric vehicle applications. Int. J. Ambient Energy 45(1), 2281613. https://doi.org/10.1080/01430750.2023.2281613 (2024).

Fobi, S. O., Agoro, S., Husain, I. & Mikail, R. Modulated model free predictive current control with constrained optimization for permanent magnet synchronous motor drives. IEEE J. Emerg. Select. Top. Power Electron. https://doi.org/10.1109/JESTPE.2025.3533497 (2025).

Jarkas, A. M. & Doss, M. A. N. Optimized PI controller tuning for improved performance in BLDC motor speed control using heuristic adaptive lyrebird optimization algorithm. ElectrEng https://doi.org/10.1007/s00202-025-02984-1 (2025).

Hemanth Kumar, B., Marakand Mohankumar, L., Raghavendra Reddy, K. & Vijay Bhanuji, B. A modified space vector PWM approach for nine-level cascaded H-bridge inverter. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 44, 2131–2149 (2018).

Hemanth Kumar, B., Marakand Mohankumar, L., Raghavendra Reddy, K. & Vijay Bhanuji, B. An improved space vector pulse width modulation for nine-level asymmetric cascaded H-bridge three-phase inverter. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 44, 2453–2465 (2019).

Naik, N. V. & Singh, S. P. A comparative study of V/f-controlled IM using two and three level bus clamped SVM. In IEEE 6th India International Conference on Power Electronics, Kurukshetra (2014).

Yahia, K., Zouzou, S.-E. & Benchabane, F. Indirect vector control of induction motor with online rotor resistance identification. Asian J. Inform. Technol. 5(12), 1410–1415 (2006).

Sharma, A. K., Gupta, R. A. & Srivastava, L. Performance of ANN based indirect vector control of induction motor drive. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 3(3), 50–57 (2007).

Wang, Z. S. & Ho, S. L. Indirect rotor field orientation vector control for induction motor drives in the absence of current sensor. In IEEE 5th International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference, Shanghai, China (2006).

Baruch, I., de la Cruz A, I. P., Garrido, R. & Nenkova, B. An indirect adaptive vector control of the induction motor velocity using neural networks. Cybern. Inform. Technol. 7(2), 57–72 (2007).

Kumar, R., Gupta, R. A. & Bhangale, S. V. Indirect vector controlled induction motor drive with fuzzy logic based intelligent controller. In IET-UK International Conference on Information and Communication Technology in Electrical Sciences, Chennai, India (2007).

Mahir, R. A., Ahmed, Z. M. & H, A. J. Indirect field orientation control of induction machine with detuning effect. Eng. Technol. 26(1), 265–277 (2008).

Marwali, M. N., Keyhani, A. & Tjanaka, W. Implementation of indirect vector control on an integrated digital signal processor-based system. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 4(2), 139–146 (2009).

Onea, A., Horga, V. & Răţoi, M. Indirect vector control of induction motor. In Proceedings of the 6th WSEAS International Conference on Simulation, Modelling and Optimization, Libson, Portugal (2006).

Ahn Kwon, Y. & Kim, S. K. A high-performance strategy for sensorless induction motor drive using variable link voltage. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 22(1), 329–332 (2007).

Farah, N. et al. A novel self-tuning fuzzy logic controller based induction motor drive system: An experimental approach. IEEE Access 7, 68172–68184 (2019).

Tarbosh, Q. A. et al. Review and investigation of simplified rules fuzzy logic speed controller of high performance induction motor drives. IEEE Access 8, 49377–49394 (2020).

Aymen, F. et al. An improved direct torque control topology of a double stator machine using the fuzzy logic controller. IEEE Access 9, 126400–126413 (2021).

Ozek, M. B. & Akalpot, Z. H. A software tool: Type-2 fuzzy logic toolbox Wiley Periodicals Inc. Firat University, Technical Education Faculty, Department of Electronics and Computer Science, 23119 (2008).

Baum, F., Lipcak, O. & Bauer, J. Hybrid overmodulation strategy for dual two-level inverter with arbitrary DC-bus voltage distribution. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 39, 11492 (2024).

Qamar, H., Qamar, H. & Ayyanar, R. Performance analysis and experimental validation of 240°-clamped space vector PWM to minimize common mode voltage and leakage current in EV/HEV traction drives. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 8(1), 196–208 (2021).

Yan, H., Yang, J. & Zeng, F. Three-phase current reconstruction for PMSM drive with modified twelve sector space vector pulse width modulation. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 37(12), 15209–15220 (2022).

Basha, Ch H., Rani, C. & Odofin, S. Analysis and comparison of SEPIC, Landsman and Zeta converters for PV fed induction motor drive applications. In 2018 International Conference on Computation of Power, Energy, Information and Communication (ICCPEIC) (IEEE, 2018).

Rinkeviciene, R. & Mitkiene, B. Design and analysis models with PID and PID fuzzy controllers for six-phase drive. World Electric Vehicle J. 15(4), 164 (2024).

Ofoli, A. R. Fuzzy-Logic Applications in Electric Drives and Power Electronics. Power Electronics Handbook 1233–1260 (Butterworth-Heinemann, 2024).

Ramesh, M. et al. A novel fuzzy assisted sliding mode control approach for frequency regulation of wind-supported autonomous microgrid. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 31526 (2024).

Kong, X. et al. Stability control of distributed drive electric vehicle based on adaptive fuzzy sliding mode. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. D: J. Autom. Eng. 238(9), 2741–2752 (2024).

Tikkani, A. & Prasad, P. V. N. Type-1 and type-2 fuzzy logic-based space vector modulation for two-level inverter fed induction motor. TELKOMNIKA (Telecommunication Computing Electronics and Control) 20(4), 901–913 (2022).

Kumar, P., et al. Predicting earthquake damage and rehabilitation intervention using adaptive fuzzy C-means-based support vector machine. In 2024 International Conference on Integrated Intelligence and Communication Systems (ICIICS) (IEEE, 2024).

Panda, A. & Singh, S. P. A three-level fuzzy-2 DTC of induction motor drive using SVPWM. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 63(3), 1467–1479 (2015).

Raja, D. & Ravi, G. Dynamic modeling and control of five phase SVPWM inverter fed induction motor drive with intelligent speed controller. J. Ambient Intell. Human. Comput. 1–11 (2020).

Basha, C. H. H. et al. Design of GWO based fuzzy MPPT controller for fuel cell fed EV application with high voltage gain DC-DC converter. Mater. Today: Proc. 92, 66–72 (2023).

Hannan, M. A. et al. Quantum-behaved lightning search algorithm to improve indirect field-oriented Fuzzy-PI control for IM drive. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 54(4), 3793–3805 (2018).

Senthilkumar, S. & Vijayan, S. High performance fuzzy based SVPWM inverter for three phase induction motor V/f speed control. Eur. J. Sci. Res. 73(4), 425–433 (2012).

Basha, C. H. H. & Rani, C. A new single switch DC-DC converter for PEM fuel cell-based electric vehicle system with an improved beta-fuzzy logic MPPT controller. Soft Comput. 26(13), 6021–6040 (2022).

Sudheer, H., Kodad, S. F. & Sarvesh, B. Regular paper Improved Fuzzy Logic based DTC of Induction machine for wide range of speed control using AI based controllers. J. Electr. Syst 12(2), 301–314 (2016).

Varga, T. et al. Optimization of fuzzy controller for predictive current control of induction machine. Electronics 11(10), 1553 (2022).

Basha, C. H. & Murali, M. A new design of transformerless, non-isolated, high step-up DC–DC converter with hybrid fuzzy logic MPPT controller. Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl. 50(1), 272–297 (2022).

Abd Ali, J. et al. Fuzzy logic speed controller optimization approach for induction motor drive using backtracking search algorithm. Measurement 78, 49–62 (2016).

Venu Gopal, B. T., Shivakumar, E. G. & Ramesh, H. R. An experimental setup for implementation of fuzzy logic control for indirect vector-controlled induction motor drive. In Advances in Control Instrumentation Systems: Select Proceedings of CISCON 2019 193–203 (Springer Singapore, 2020).

Magzoub, M. et al. An experimental demonstration of hybrid fuzzy–fuzzy space–vector control on AC variable speed drives. Neural Comput. Appl. 31, 777–792 (2019).

Basha, C. H. & Rani, C. Application of fuzzy controller for two-leg inverter solar PV grid connected systems with high voltage gain boost converter. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. Rev. 14(2), 8 (2021).

Hussain, S. & Bazaz, M. A. Adaptive neural Type II fuzzy logic-based speed control of induction motor drive. In Ambient Communications and Computer Systems: RACCCS 2017 (Springer Singapore, 2018).

Singh, S. P. & Durgasukumar, G. An improved performance of F2DTC induction motor using five-level SVM. In 2016 IEEE International Conference on Power Electronics, Drives and Energy Systems (PEDES) (IEEE, 2016).

El Ouanjli, N. et al. Improved DTC strategy of doubly fed induction motor using fuzzy logic controller. Energy Rep. 5, 271–279 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.T., R.R.K., K.V.G.R.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Investigation, Writing- Original draft preparation. C.H.N.S.K., B.S.G.: Data curation, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Writing—Review and Editing. M.B., M.B.T.: Project administration, Supervision, Resources, Writing—Review and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tikkani, A., Karasani, R.R., Venkata Govardhan Rao, K. et al. Fuzzy-2 deployment in indirect vector control and hybrid space vector modulation for a two-level inverter fed induction motor drive. Sci Rep 15, 13379 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96600-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96600-8