Abstract

As lifestyle-related diseases like obesity, dyslipidemia, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease are increasing globally, the demand for developing therapeutic agents and health foods remains high. However, there is a growing concern worldwide regarding the use of animals for biological testing. Herein, we developed a method using the silkworm, Bombyx mori, to evaluate the effects of compounds on improving obesity and lipid metabolism. A silkworm obesity and lipid metabolism disorder (SOLD) model, fed a 10% glucose diet for 72 h showed increased fat body weight and accumulation of neutral fat in the hemolymph and fat body. Administration of fenofibrate reduced neutral fat levels in the hemolymph, and epigallocatechin gallate reduced neutral fat levels in the hemolymph and fat body. Silkworms with improved lipid metabolism, exhibited activation of lipoprotein lipase in muscle tissue, and decreased activities of acetyl-CoA carboxylase, and activation of AMPK in the fat body. Furthermore, enhanced fatty acid beta-oxidation contributed to the promotion of lipolysis. These effects and mechanisms of action observed in silkworms are similar to those found in mammals. These results demonstrate the usefulness of the evaluation system in screening materials for their anti-obesity and lipid metabolism improvement effects using the SOLD model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Today, more than 2.5 billion people worldwide are overweight or have obesity1, excessive fat accumulation, posing risk factors for various diseases like type II diabetes, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines people with overweight as a body mass index (BMI) over 25 kg/m² and people with obesity as over 30 kg/m². However, in Asia, individuals with a BMI < 25 kg/m2 face increasing prevalence of hyperglycemia, impaired glucose tolerance, lipid metabolism disorder, and metabolic syndrome due to excessive visceral fat accumulation2,3. Most obesity cases are associated with lifestyle disorders, such as overeating and lack of exercise. Moreover, low-income countries witness a rapid rise in people with obesity due to high-carbohydrate diets centered on staple crops1. Weight loss can prevent or slow down the progression of obesity-related diseases, thus, improving dietary habits holds potential to reduce health issues and associated medical costs4.

In recent years, various functional ingredients with anti-obesity and lipid metabolism improvement properties have been discovered in natural products; specifically, there are considerable reports on polyphenols found in plants. Tea polyphenols are known to inhibit lipid absorption, while tea catechins, chlorogenic acid in coffee, capsaicin in chili pepper, and curcumin in turmeric inhibit fat accumulation and promote its degradation5. While these pharmacological activities have mostly been verified through experiments on mammals, there is a growing movement to abolish animal testing due to animal welfare concerns. Consequently, alternative methods to animal testing are being advocated6. The primary alternative method is cell culture systems, but accurately predicting biological reactions involving interactions between tissues and organs is challenging. Insects, however, have attracted attention as pathological models with no animal ethics issues.

Insects may appear vastly different from humans, but they possess tissues and organs crucial for glucose and lipid metabolism, with evolutionarily conserved cell signaling pathways. For instance, insects feature a midgut analogous to the mammalian digestive tract, and a fat body analogous to the mammalian liver and adipose tissue. Drosophila melanogaster serves as a representative model organism that demonstrate diet-induced obesity similar to humans when fed high-sugar or high-fat diets, exhibiting characteristics, such as hyperglycemia, increased triglyceride (TG) levels, activation of inflammatory signals, and insulin resistance7,8,9,10,11,12. Consequently, Drosophila are utilized as models for obesity and fatty liver disease to evaluate the effects of plant extracts and lactic acid bacteria13,14,15,16. Additionally, Drosophila fed a high-fat diet supplemented with fenofibrate (FBT), a drug used to treat hyperlipidemia, exhibit lower TG levels in their bodies16, through the precise mechanism remains unclear. However, their extremely small body size poses challenges in measuring food intake and collecting tissues. In mammals, the liver, muscle, and adipose tissue play crucial roles in lipid metabolism, underscoring the importance of assessing metabolic changes in each tissue in an insect model. Moreover, since food intake significantly influences fat accumulation and degradation, precise quantification becomes imperative. The silkworm, Bombyx mori, has attracted attention as an insect model due to its larger body size.

Fifth instar silkworms are large, measuring about 4–6 cm, facilitating the easy collection of hemolymph, fat bodies, and muscle. Moreover, these silkworms, daily, consume food equivalent to their own body weight, experiencing significant growth from 1 g after molting to 5 g within three days during which fat accumulates in the fat body. This makes silkworms ideal for verifying the effects of diet-induced inhibition of fat accumulation and degradation, a process that typically spans 10–25 days in Drosophila, within a few days. Furthermore, when fed an artificial diet containing 10% glucose (10GD) for 18 h, silkworms display symptoms similar to human lipid metabolism disorders, including hyperglycemia, increased fat body weight, and increased TG levels in fat bodies and hemolymph17. Despite these similarities, currently, there are no established evaluation systems for lipid metabolism enhancers utilizing silkworms.

In this study, we established a silkworm with obesity and lipid metabolism disorder (SOLD) model by feeding the worms with a 10GD for 72 h. Then, we evaluated the usefulness of the model using the therapeutic effect of FBT, and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG). FBT is a hyperlipidemic drug that lowers blood TG by activating muscle lipoprotein lipase (LPL)18. It inhibits fat synthesis and increases β-oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in the muscle and liver by activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-α19. EGCG is a food ingredient with reported fat-reducing effects in humans and other mammals. It inhibits fat synthesis and enhances β-oxidation through AMPK activation in the liver and muscle20,21,22. The other compounds used were AICAR and antidiabetic drug metformin (MT) as an activator of AMPK, and antidiabetic drug pioglitazone (PG), which have no lipid-lowering effect.

Results

Silkworms develop obesity and dyslipidemia when fed a 10% glucose diet (10GD)

Silkworms were divided into groups fed either a normal diet (ND) or a 10GD on the first day of the fifth instar (Fig. 1A). The 10GD group showed a decreased food intake and body weight compared to the ND group (Fig. 1B and C). Fat body weight was higher in the 10GD group (Fig. 1D and E) showing a time-dependent increase, peaking at 72 h. Furthermore, levels of neutral fat (NF) in both the fat body (Fig. 2A) and hemolymph (Fig. 2B), as well as levels of hemolymph sugar (Fig. 2C) and bombyxin, a silkworm insulin-like peptide (Fig. 2D), were significantly increased in silkworms fed with 10GD for 72 h compared to the ND group. These findings suggest that silkworms reared on a 10GD for 72 h develop a phenotype similar to obesity and lipid metabolism disorders observed in mammals.

Increased fat body weight in silkworms fed with 10% glucose diet. (A) Experimental design. Silkworms were divided into groups fed either a normal diet (ND) or a 10% glucose diet (10GD) for 72 h (n = 3/group). (B) Food intake, (C) body weight, (D) fat body weight were measured every 24 h. (E) Photographs of the fat body at 72 h. Data represent mean ± SD. Significant differences between groups were evaluated using a t-test. ##p < 0.01, #p < 0.05 compared with the ND group, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, compared with the 10GD group.

Development of hyperlipidemia in silkworms fed with 10% glucose diet. Silkworms were fed a normal diet (ND), 10% glucose diet (10GD) for 72 h (n = 5/group), and measured (A) neutral fat in the fat body and (B) in the hemolymph, (C) total sugar in the hemolymph, (D) bombyxin in the hemolymph. Data represent mean ± SD. Significant differences between groups were evaluated using a t-test. ##p < 0.01, #p < 0.05 compared with the ND group.

Evaluation of the effects of hyperlipidemia drugs and anti-obesity functional ingredients on lipid metabolism in the silkworm obesity and lipid metabolism disorder (SOLD) model.

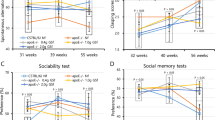

To assess the efficacy of the SOLD model, silkworms were fed with 10GD supplemented with FBT, EGCG and the AMPK activator AICAR, a target similar to EGCG, and MT and PG, both antidiabetic drugs, for 72 h (n = 10/group) (Fig. 3A).

In the SOLD silkworms, food intake and body weight decreased (Supplementary Fig. 1 A and B), while fat body weight, NF levels in hemolymph and fat bodies, and hemolymph sugar levels significantly increased compared to the ND group (Fig. 3B–D). In the FBT group, the hemolymph NF levels decreased in a concentration-dependent manner compared to the untreated group (Fig. 3D). The EGCG group exhibited a concentration-dependent decrease in NF levels in the fat bodies and a trend in hemolymph (p = 0.08) (Fig. 3C and D) and showed a trend toward lower fat body weight compared to the untreated group (Fig. 3B). Moreover, hemolymph sugar levels tended to decrease for both compounds compared to the untreated group (Supplementary Fig. 1 C). The AICAR group showed a significant reduction in fat body weight (Fig. 3B) and NF levels in the fat bodies (Fig. 3C). However, no improvement was observed in the MT and PG groups. These results indicate that the effects of FBT and EGCG on the SOLD model resemble their effects on mammals.

Evaluation of the lipid-lowering effect of various drugs in the hemolymph and fat body in the silkworm obesity and lipid metabolism disorder (SOLD) model. (A) Experimental design. Silkworms were fed a normal diet (ND), a 10% glucose diet (10GD), or 10GD containing fenofibrate (FBT; 1, 2, and 20 mg/kg/days), epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG; 20, 200 and 400 mg/kg/days), AICAR (20, 200, and 400 mg/kg/days), metformin (MT; 10, 20, and 200 mg/kg/days), and pioglitazone (PG; 10, 20, and 200 mg/kg/days) for 72 h (n = 10/group). (B) Fat body weight, (C) neutral fat in the fat body and (D) in the hemolymph were measured at 72 h (n = 5). Data represent mean ± SD. Significant differences between groups were evaluated using a Dunnett test. ##p < 0.01, #p < 0.05 compared with the ND group, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, compared with the 10GD group.

Mechanism of action underlying the effects of FBT and EGCG on the SOLD model

To clarify the mechanism of action of FBT and EGCG on the SOLD model, we evaluated the activation status of enzymes involved in lipid synthesis signaling in fat bodies using western blotting (Fig. 4A). Compared to the ND group, the SOLD model showed increased fatty acid synthase (FAS) level (Fig. 4B), along with decreased levels of the phosphorylated acetyl-CoA carboxylase (p-ACC) (Fig. 4C), and phosphorylated AMPK (p-AMPK) (Fig. 4D). The FBT group displayed an upward trend in p-AMPK and p-ACC levels compared to the untreated group. Similarly, the EGCG group showed higher p-AMPK and p-ACC levels compared to the untreated group (p < 0.01, p < 0.05). These compounds act similarly to their effects in mammals. The AICAR group showed a decreasing trend in FAS level and a significant increase in p-AMPK and p-ACC levels. While the MT group showed an increasing trend in p-AMPK level, the PG group did not differ from the untreated group.

Expression levels of enzymes in the fatty acid synthesis pathway and AMPK in the silkworm obesity and lipid metabolism disorder (SOLD) model administrated various drugs. (A) Western blotting analysis was performed to evaluate the expression levels of (B) fatty acid synthase (FAS), (C) phosphorylated acetyl-CoA carboxylase (p-ACC), (D) phosphorylated AMP-activated protein kinase (p-AMPK) in the fat body of the SOLD model fed 10GD or 10GD containing FBT (20 mg/kg/days), EGCG (400 mg/kg/days), AICAR (400 mg/kg/days), MT (200 mg/kg/days), and PG (200 mg/kg/days) for 72 h. Relative expression levels of the proteins were calculated by normalization to β-actin expression. Data represent mean ± SD. Significant differences between groups were evaluated using a t-test (n = 4). ##p < 0.01, #p < 0.05 compared with the ND group, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, compared with the 10GD group.

LPL activity

In mammals, FBT promotes TG degradation in the blood by activating LPL18 and EGCG decreases LPL activity in adipose tissue23 and green tea, rich in EGCG, increases LPL activity in muscle24.

In the SOLD model, LPL activity showed no significant differences in either fat body (Fig. 5A) or muscle (Fig. 5B) compared to the ND group. However, in the FBT group, there was an increasing trend in muscle LPL activity. The EGCG group showed a decreasing trend in fat body LPL activity (p < 0.05) and a significant increase in muscle LPL activity compared to the 10GD group (p < 0.01). Furthermore, the AICAR group showed a significant decrease in fat body LPL and a tendency toward increased muscle LPL. Conversely, there were no changes observed in the MT and PG groups compared to the 10GD group. These results suggest that FBT and EGCG regulate AMPK activation and LPL activity, indicating their action on LPL activity in the silkworm mirrors their effects on mammalian LPL.

LPL activity in the fat body and muscle in the silkworm obesity and lipid metabolism disorder (SOLD) model after drug administrated. Silkworms were fed a normal diet (ND), a 10% glucose diet (10GD), or 10GD containing FBT (20 mg/kg/days), EGCG (400 mg/kg/days), AICAR (400 mg/kg/days), MT (200 mg/kg/days), and PG (200 mg/kg/days), respectively for 72 h (n = 5/group). (A) LPL activity in fat bodies and (B) in muscles were measured at 72 h. Data represent mean ± SD. Significant differences between groups were evaluated using a t-test. *p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 compared with the 10GD group.

Fatty acid oxidation activity

FBT and EGCG are known to promote the β-oxidation of fatty acids in mammals. To determine whether this effect is present in the SOLD model, we measured the respiratory quotient (RQ) as an indicator of fatty acid oxidation. Silkworms were initially fed with 10 GD for 72 h to induce obesity and dyslipidemia. Subsequently, they were fed with ND mixed with FBT, EGCG, or AICAR (n = 5/group). During this period, O2 consumption and CO2 emissions were monitored using a metabolic measurement system (MK- 5000RQ/MS) designed for small animals (Fig. 6A). RQ was calculated by dividing CO2 emissions by O2 consumption (RQ = VCO2/VO2). Data collection was paused for the first 3 h after switching to the ND to allow the silkworms to acclimate to the measurement environment. Data were then collected continuously for 24 h. RQ values represent the average of each 8-h period divided into 3 segments over the 24-h periods.

In the SOLD model, RQ decreased over time from the start of measurements. In the non-treated group, it remained above 1 at 17–24 h. Conversely, in the FBT, EGCG, and AICAR groups, the RQ at 17–24 h was below 1 (Fig. 6B). The RQ at 17–24 h was lowest in the EGCG and AICAR groups, which aligns with the observation that both groups exhibited the lowest NF levels in hemolymph and fat bodies (Fig. 6C–E).

Respiratory quotient in the silkworm obesity and lipid metabolism disorder (SOLD) model administered various drugs. (A) Experimental design: Silkworms were initially fed with a 10GD for 72 h (n = 5/group), followed by a switch to either a ND or ND supplemented with FBT (20 mg/kg/days), EGCG (400 mg/kg/days), AICAR (400 mg/kg/days), MT (200 mg/kg/days), and PG (200 mg/kg/days). (B) RQ was measured for 24 h after the diet switch. At the end of the measurement, fat bodies and hemolymph were collected, and (C) fat body weight, (D) neutral fat in the fat body and (E) in the hemolymph were measured. Data represent mean ± SD. Significant differences between groups were evaluated using a t-test. **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 compared with the 10GD group.

Discussion

Establishment of the SOLD model

In this study, we aimed to construct an evaluation system for screening compounds that could improve obesity and lipid metabolism disorders, using the silkworm model. Insects possess fat bodies that serve analogous functions of mammalian adipose tissue and liver. Sugars ingested are metabolized into trehalose within the fat body, stored in the hemolymph, or converted into TG and glycogen, which accumulate in the fat body25. Silkworms fed with 10GD showed a progressive increase in fat body weight over time (Fig. 1D), alongside elevated levels of hemolymph bombyxin, suggesting enhanced trehalose uptake into fat bodies and increased fat synthesis. Moreover, the 10GD group exhibited higher levels of hemolymph sugar and NF in fat body and hemolymph (Fig. 1F–H). In humans, obesity is characterized by excessive body fat accumulation, typically with a BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m21, yet there is a growing population of individuals with high visceral fat levels despite a low BMI26. Silkworms fed with 10GD showed reduced overall body weight but increased fat body weight compared to those on a ND, suggesting that the SOLD model bears similarity to visceral fat obesity in human.

The pathways for fatty acid biosynthetic are shared between insects and mammals. In mice with high-sugar or high-fat diets induced obesity, there is an increase in the activity of key enzymes for fatty acid synthesis, such as FAS and ACC. Conversely, the activity of AMPK, a signaling protein that inhibits FAS and ACC, decreases27,28,29,30,31,32. In the SOLD model, compared to the ND group, there was an increase in FAS expression and a decrease in the inactive form of ACC (p-ACC), while the activated form of AMPK (p-AMPK), responsible for phosphorylating ACC, decreased (Fig. 4B–D). These results suggest that the SOLD model induces diet-induced obesity through mechanisms similar to those observed in mammals.

Usefulness of the SOLD model as an animal model for obesity

To assess the utility of the SOLD model, we evaluated the effects of FBT, a drug for hyperlipidemia, and EGCG, known for its ability to inhibit fat accumulation in humans. FBT exhibits various lipid-improving effects, including lowering blood TG levels and increasing blood HDL cholesterol, attributed to the activation of PPARα. PPARα is strongly expressed in tissues with active β-oxidation, such as liver, kidney, skeletal muscle, and heart, in humans33. Its activation increases the production and activity of LPL in muscle and adipose tissue by decreasing the production of ApoC III, thus, facilitating TG degradation in blood and free fatty acid uptake in tissues18. Furthermore, PPARα activation enhances β-oxidation and suppressing TG synthesis by activating AMPK in the liver and muscle19. In the SOLD model, administration of FBT led to a concentration-dependent decrease in hemolymph NF levels (Fig. 3D) alongside an increasing trend in p-AMPK and p-ACC in fat bodies (Fig. 4B–D). Furthermore, the FBT-treated group showed an increasing trend in muscle LPL activity (Fig. 5B) and a decreasing trend in RQ (Fig. 6B) compared to the untreated group, suggesting an increase in β-oxidation. The effects and mechanisms of action of FBT observed in the SOLD model closely resembled those seen in mammals.

EGCG, a polyphenol abundant in green tea, is recognized for its ability to lower body weight and prevent obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases34. In mice with diet-induced obesity, EGCG decrease fat accumulation, blood TG, cholesterol, liver TG, blood glucose levels and the intestinal absorption of lipids35,36,37. EGCG primary mechanisms involve inhibiting fatty acid synthesis by activating AMPK in the liver, skeletal muscle and adipose tissue, as well as enhancing β-oxidation20,21,22; additional effects include decreased LPL activity in adipose tissue23, increased expression of PPARα in muscle38and a decrease in RQ39. Additionally, green tea increases LPL activity in muscle tissue24. In the SOLD model, administration of EGCG led to a reduction in NF levels in the fat body and a trend reducing NF in the hemolymph (Fig. 3C and D). Moreover, the EGCG-treated group showed increased p-AMPK and p-ACC in the fat body (Fig. 4C and D), decreased fat body LPL activity (Fig. 5A), increased muscle LPL activity (Fig. 5B), and decreased RQ (Fig. 6B). The effects of EGCG on lipid metabolism in the SOLD model were consistent with those in the mammalian model with obesity.

In this study, the effects of FBT and EGCG on the SOLD model demonstrated increased muscle LPL activity and decreased RQ. High RQ and low RQ indicate fat synthesis and β-oxidation, respectively40. Our results suggest that FBT and EGCG influenced myocytes LPL in silkworm, promoting the uptake of hemolymph NF and fat oxidation in muscle tissue. In the flying insect, LPL is found in the fat bodies, muscle and ovaries41,42. Diglycerides (DG), degraded by fat body lipase, bind to lipophorin, an insect lipoprotein in hemolymph and are uptaken into the muscle cells via myocyte membrane LPL for ATP production43,44. Our report is the first to suggest that in the silkworm, LPL is expressed in muscle and involved in ATP production.

In the SOLD model, effects similar to those for FBT and EGCG were observed when AICAR, an AMPK activator, was administered. However, MT, which has an AMPK-activating effect, showed an increasing trend in p-AMPK and a decreasing trend in fat body accumulation and the TG level in the fat body at the highest concentration (200 mg/kg/day), indicating that higher concentrations may have a significant effect. However, toxicity in the form of reduced food intake and body weight occurred at higher doses. In Drosophila, MT administration was reported to increase p-AMPK expression and decrease TG in the body, but to increase lethality in a concentration-dependent manner45. MT inhibits mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I, causing an increase in the AMP/ATP ratio and phosphorylation of the AMPK α-subunit46. In silkworms, MT toxicity resulting from the inhibition of the respiratory chain complex appears at lower concentrations compared with those observed inhibiting fat accumulation, suggesting that the fat-lowering effect of metformin was not captured.

In the SOLD model, the effective dose of FBT (20 mg/kg/day) for improving lipid metabolism was approximately one-fifth of that in mice (100 mg/kg/day47) and approximately 10 times that administered in humans (1.8–2.7 mg/kg/day). The effective dose of EGCG in the SOLD model (200–400 mg/kg/day) was about 4 times that used in mice (50–100 mg/kg/day21) and approximately 20 times that used in humans (10 mg/kg/day). Despite these differences, the effective doses of both compounds in the SOLD model were comparable to those in mice or humans, suggesting their potential utility as alternative models.

The SOLD model offers a means to evaluate lipid metabolism with a small sample, within a short timeframe, and at a low cost, and without encountering animal ethics issues. These results indicate the utility of the SOLD model for screening therapeutic drugs and functional food ingredients aimed at improving obesity and lipid metabolism disorders.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Trehalase from porcine kidney and palmitoyl coenzyme A lithium salt were purchased from Sigma Aldrich Japan, Co, LLC. (Tokya, Japan). AICAR (S7863) was purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Houston TX, USA). (−)-Epigallocatechin gallate hydrate, pioglitazone hydrochloride, fenofibrate were obtained from Tokyo Chemical Industry, Co. (Tokyo, Japan). D-(+)-glucose was purchased from Nacalai Tesque, Inc. (Kyoto, Japan). Metformin hydrochloride, trehalose dihydrate, oil Red O, 4%-paraformaldehyde phosphate buffer solution, heparin sodium, 4-methylumbelliferyl oleate and 2-propanol were obtained from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). Primary antibodies FAS (#3180), p-AMPK (#2535 T), p-ACC (#11818 T), and β-actin (#4967) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, USA). Secondary antibodies, goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) antibody, and HRP conjugate (SA00001 - 2) were purchased from Cosmo Bio, Co. (Tokyo, Japan). The TaKaRa BCA Protein Assay Kit was obtained from Takara Bio, Inc. (Shiga, Japan).

Silkworm rearing conditions and diet Preparation

Silkworms (hybrid race: Kin-Shu × Sho-Wa) were kindly provided by Atsumaru Holdings NSP Yamaga Plant (Atsumaru Inc., Kumamoto, Japan). Upon hatching, larvae were reared to the fifth instar on an artificial diet, SilkMate PM (Nosan Corporation), within plastic containers maintained at 25–27 °C and 50–70% humidity within a 12-h light–dark cycle. All experiments performed using larvae (2.5 ± 0.2 g), unless otherwise mentioned.

An artificial diet was prepared following the instructions provided by the feed company. SilkMate PM was blended with water at a 1:3 ratio and subsequently steamed in an autoclave at 105 °C for 20 min. For the glucose diet, SilkMate PM, glucose, and water were mixed to achieve an equivalent weight of sugar, then subjected to autoclaving. The compounds were mixed into the 10GD just before feeding to the silkworms.

Hemolymph and fat body collection methods

Hemolymph (10 µL) was collected from the larva’s proleg by prickig with a 30 G needle (insulin syringe; Becton, Dickinson and Company) and immediately frozen on dry ice, then stored at − 20 °C. The fat bodies were collected as follows. After the silkworm was placed into a state of temporary death using dry ice to stop its movement, it was cut open from the dorsal side, and the midgut was removed. All the fat bodies were scraped off with flat tweezers. The fat bodies were weighed and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at − 80 °C.

Determination of hemolymph trehalose and glucose levels

The hemolymph trehalose concentration was determined by the previously described method with modifications48. Hemolymph (2 µL) was diluted 100-fold in buffer (5 mM Tris, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, and pH 6.7), then incubated at 80 °C for 3 min before returning to room temperature. Hemolymph solution (100 µL) was mixed with 100 µL of porcine trehalase solution (10 mU/mL; diluted in buffer), incubated overnight at 37 °C, and the resulting glucose production was measured using the Glucose CII Test Wako (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Tokyo, Japan). Trehalose concentration calculated from a trehalose calibration curve prepared using the same method as sample. Glucose concentration was also measured using the Glucose CII Test Wako. For this, hemolymph (2 µL) was added to a frozen 96 well plate, followed by the addition of chromogenic solution (200 µL). After incubation at room temperature for 15 min, absorbance was measured at 505 nm.

Determination of the neutral fat levels in hemolymph

Neutral fat (NF) levels in the hemolymph were measured using LabAssay™ Triglycerides (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Tokyo, Japan). Hemolymph (2 µL) was added to a frozen 96-well plate, followed by the addition of chromogenic solution (300 µL). After incubating at room temperature for 5 min, absorbance was measured at 600 nm.

Production of anti-bombyxin monoclonal antibody

Anti-bombyxin monoclonal antibody was prepared by the method from Mizoguchi et. al49 with modifications. A synthetic peptide (II-10; GIVDECCLRP) consisting of the N-terminal to the 10 amino acids of the bombyxin-II A chain was conjugated with BSA or KLH using EDC and NHS. BALB/c mice were immunized with II-10-KLH and an adjuvant (Titer MAX Gold) (17.5 µg/100 µL/mouse) twice and their spleen cells were fused with myeloma cell (P3U1) cells. Hybridomas were screened positive for II-10-BSA by ELISA and cells producing II-10 monoclonal antibody were isolated. Cells were injected the abdominal cavity of mice previously primed with pristine, and the monoclonal antibody from ascitic fluid were purified using a protein G-conjugated column (Spin column-based Antibody Purification Kit (Protein G) CosmoBio, Tokyo, Japan). Blood IgG from immunised mice was purified and HRP-labelled and used as an anti-II-10 polyclonal antibody.

Determination of bombyxin level in hemolymph

100 µL of anti-bombixin (II-10) monoclonal antibody (5 µg/mL) was added to 96-well immunoplates and incubated overnight at 4 °C. After three washes with PBS-T, 100 µL of hemolymph diluted 100-fold with PBS was added and incubated for 1 h. After three washes, 100 µL of HRP-conjugated anti-II-10 polyclonal antibody was added and incubated for 1 h. After three washes, the color was developed with WSE-7145 EzELISA TMB (ATTO, Tokyo, Japan) and the absorbance at 450 nm was measured. bombyxin concentration was calculated from the calibration curve of bombyxin (II-10) prepared using the same measurements.

Western blotting

The fat body (frozen weight 50 mg) was crushed in 1 mL of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP- 40 Substitute, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, protease inhibitor cocktail I, phosphatase inhibitor cocktail II, pH 7.6) for 30 s using a polytron homogenizer. After incubating on ice for 30 min, the samples were centrifuged (14,000 g, 10 min, 4 °C) and the protein concentration of the supernatant was determined using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay. Each sample was diluted with sample buffer (125 mM Tris-HCl, 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, 0.004% bromophenol blue, 50 mM DTT, and pH 6.8) and water to adjust the protein concentration. The samples were then heat-treated at 90 °C for 5 min and subjected to SDS-PAGE on 10% polyacrylamide gel. Proteins in the gel were transferred to a PVDF membrane, incubated with primary antibodies and secondary antibodies, and bands of the target proteins were detected using SuperSignal TM Chemiliuminescent HRP Substrates (Thermo Fisher Scientific Logo). Bands were quantified using Image J.

Oil red O staining of the silkworm NF in fat bodies

NF staining was performed by the previously described method with modifications17. Fat bodies were immediately immersed in 4% formaldehyde upon removal and fixed overnight at 4 °C. The samples were rinsed in phosphate buffer (137 mM NaCl, 8.1 mM Na2HPO4, 2.68 mM KCl, 1.47 mM KH2PO4, and pH 7.4), treated with 60% 2-propanol aqueous solution for 1 min, and then stained with Oil red O stain solution (1.8 mg of Oil red O in 1 mL of 60% 2-propanol aqueous solution) for 20 min at room temperature. After being washed three times with 60% 2-propanol aqueous solution, the samples were immersed in 100% 2-propanol and sonicated for 30 min. Following centrifugation (10,000 g, 3 min), absorbance was measured at 490 nm, and triglyceride levels were calculated based on absorbance per gram of fat body.

Measurement of lipoprotein lipase activity

Sample preparation for the lipoprotein lipase (LPL) activity assay was performed by modification of the previously described method41. Fat body and muscle (frozen weight 100 mg) were homogenized in 1 mL of ice-cold heparin solution (0.25 M sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 3 mM Tris-HCl, 2% BSA, 2 U/ml heparin sodium, and pH 7.5) using a polytron homogenizer. After incubation at 37 °C for 1 h, the samples were centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected as the enzyme solution. Protein concentrations of the enzyme solutions were determined using the BCA assay and then diluted in phosphate buffer (0.2 M Na2HPO4 12H2O, 0.2 M NaH2O4 2H2O, and pH 7.4) to adjust the protein concentration of each sample.

LPL activity was assessed using a fluorescence method with 0.5 mM oleic acid 4-methylumbelliferyl solution dissolved in phosphate buffer as the substrate. Upon mixing of enzyme solution (100 µL) and substrate solution (100 µL) in a 96-well microplate, fluorescence intensity (ex/em = 355 nm/460 nm) was promptly measured for 30 min at 2 min intervals. The ratio of fluorescence intensity at 30 min to the fluorescence intensity at 0 min was used as the measure of LPL activity.

Measurement of respiratory quotient

The method from Hanatani et al. was modified50. Measurements were performed using a metabolic measurement system designed for small animals (MK- 5000RQ/MS model, Muromachi Machinery Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at a room temperature of 26 °C within a 12-h light–dark cycle. Silkworms fed with 10GD for 72 h were placed in groups of five in closed cages and provided with a ND, with or without the sample. Three hours after switching the diet, oxygen consumption (VO2) and carbon dioxide production (VCO2) were recorded every 5 min for 24 h. The respiratory quotient (RQ) was calculated as the ratio of VO2 per VCO2.

Statistical analysis

All data were presented as the mean ± SD of three replicates. Measurements of food intake and RQ were averaged across the five silkworms. Data were analyzed with 2-group comparisons of variables using a t-test, with multiple comparisons using 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett test, with as statistical significance set at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

World Health Organization (WHO). Obesity and overweight. (2024). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

Zhu, L. et al. Lean yet unhealthy: Asian American adults had higher risks for metabolic syndrome than Non-Hispanic white adults with the same body mass index: evidence from NHANES 2011–2016. Healthcare 9, 1518. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9111518 (2021).

Fan, J. G., Kim, S. U. & Wang, V. W. S. New trends on obesity and NAFLD in Asia. J. Hepatol. 67, 862–873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.06.003 (2017).

Lee, M. et al. The cost-effectiveness of pharmacotherapy and lifestyle intervention in the treatment of obesity. Obes. Sci. Pract. 6, 162–170. https://doi.org/10.1002/osp4.390 (2020).

Ohishi, T. et al. The beneficial effects of principal polyphenols from green tea, coffee, wine, and curry on obesity. Molecules 26, 453. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26020453 (2021).

Dellambra, E. et al. Non-Animal models in dermatological research. ALTEX 36. 177–202. https://doi.org/10.14573/altex.1808022 (2018).

Elbrense, H., Montaser, O., El-Aasr, M. & Meshrif, W. S. Potential anti-diabetic effect of certain plant extracts from the Egyptian flora on type II diabetes using Drosophila melanogaster as an animal model. IJCBR 5, 121–133 (2021).

Lourido, F., Quenti, D., Salgado-Canales, D. & Tobar, N. Domeless receptor loss in fat body tissue reverts insulin resistance induced by a high–sugar diet in Drosophila melanogaster. Sci. Rep. 11, 3263. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-82944-4 (2021).

Buescher, J. L. et al. Evidence for transgenerational metabolic programming in Drosophila. Dis. Model. Mech. 6, 1123–1132. https://doi.org/10.1242/dmm.011924 (2013).

Rovenko, B. M. et al. High sucrose consumption promotes obesity whereas its low consumption induces oxidative stress in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Insect Physiol. 79, 42–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinsphys.2015.05.007 (2015).

Reis, T. Effects of synthetic diets enriched in specific nutrients on Drosophila development, body fat, and lifespan. PLOS One. 11, e0146758. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0146758 (2016).

Woodcock, K. J. et al. Macrophage-Derived upd3 cytokine causes impaired glucose homeostasis and reduced lifespan in Drosophila fed a Lipid-Rich diet. Immunity 42, 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2014.12.023 (2015).

Kayashima, Y. et al. Tea polyphenols ameliorate fat storage induced by high-fat diet in Drosophila melanogaster. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 4, 417–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrep.2015.10.013 (2015).

Azuma, M. et al. RNA-seq analysis of diet-driven obesity and anti-obesity effects of Quercetin glucoside or Epigallocatechin gallate in Drosophila adults. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 23, 857–876. https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_201901_16901 (2019).

Wongchum, N. et al. Hydroethanolic Cyperus rotundus L. extract exhibits anti-obesity property and increases lifespan expectancy in Drosophila melanogaster fed a high-fat diet. J. HerbMed Pharmacol. 11, 296–304. https://doi.org/10.34172/jhp.2022.35 (2022).

Asiimwe, O. H. et al. Anti-obesity effects of Erythrina abyssinica stem bark extract in flies exposed to a high fat diet. Heliyon 8, e09886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09886 (2022).

Matsumoto, Y. et al. Diabetic silkworms for evaluation of therapeutically effective drugs against type II diabetes. Sci. Rep. 5, 10722. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep10722 (2015).

Duval, C., Müller, M. & Kersten, S. PPARα and dyslipidemia. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell. Biol. Lipids. 1771, 961–971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.05.003 (2007).

Chen, W. L. et al. Fenofibrate lowers lipid accumulation in myotubes by modulating the PPARα/AMPK/FoxO1/ATGL pathway. Biochem. Pharmacol. 84, 522–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2012.05.022 (2012).

Murase, T., Misawa, K., Haramizu, S. & Hase, T. Catechin-induced activation of the LKB1/AMP-activated protein kinase pathway. Biochem. Pharmacol. 78, 78–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2009.03.021 (2009).

Takagaki, A. et al. Effects of microbial metabolites of (–)-Epigallocatechin gallate on glucose uptake in L6 skeletal muscle cell and glucose tolerance in ICR mice. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 42, 212–221. https://doi.org/10.1248/bpb.b18-00612 (2019).

Li, F. et al. EGCG reduces obesity and white adipose tissue gain partly through AMPK activation in mice. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 1366. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2018.01366 (2018).

Lee, M. S., Kim, C. T. & Kim, Y. Green tea (–)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate reduces body weight with regulation of multiple genes expression in adipose tissue of diet-induced obese mice. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 54, 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf402004x (2009).

Serisier, S. et al. Effects of green tea on insulin sensitivity, lipid profile and expression of PPARα and PPARγ and their target genes in obese dogs. Br. J. Nutr. 99, 1208–1216. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000711450786238 (2008).

Bayliak, M. M. et al. Interplay between diet-induced obesity and oxidative stress: comparison between Drosophila and mammals. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part. Mol. Integr. Physiol. 228, 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2018.09.027 (2019).

Tchernof, A. & Després, J. P. Pathophysiology of human visceral obesity: an update. Physiol. Rev. 93, 359–404. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00033.2011 (2013).

Ghareghani, P. et al. Aerobic endurance training improves nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) features via miR-33 dependent autophagy induction in high fat diet fed mice. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 12, 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orcp.2017.01.004 (2018).

Liu, C. et al. Flavonoid-Rich extract of Paulownia fortunei flowers attenuates diet-induced hyper liquidemia, hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance in obesity mice by AMPK pathway. Nutrients 9, 959. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9090959 (2017).

Inamdar, S. et al. Vitexin alleviates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by activating AMPK in high fat diet fed mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 519, 106–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.08.139c (2019).

Prakash, S. et al. Amelioration of diet-induced metabolic syndrome and fatty liver with sitagliptin via regulation of adipose tissue inflammation and hepatic Adiponectin/AMPK levels in mice. Biochimie 168, 198–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2019.11.005 (2020).

Lee, H. A. et al. Ganoderma lucidum extract reduces insulin resistance by enhancing AMPK activation in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Nutrients 12, 3338. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113338 (2020).

Li, T. et al. Milk fat globule membrane attenuates High-Fat Diet-Induced obesity by inhibiting adipogenesis and increasing uncoupling protein 1 expression in white adipose tissue of mice. Nutrients 10, 331. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10030331 (2018).

Grygiel-Górniak, B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and their ligands: nutritional and clinical implications - a review. Nutr. J. 13 https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-13-17 (2014).

Yang, C. S. et al. Mechanisms of body weight reduction and metabolic syndrome alleviation by tea. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 60, 160–174. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201500428 (2016).

Chen, Y. K. et al. Effects of green tea polyphenol (–)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate on newly developed High-Fat/Western-Style Diet-Induced obesity and metabolic syndrome in mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 59, 11862–11871. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf2029016 (2011).

Grove, K. A., Sae-Tan, S., Kennett, M. J. & Lambert, J. D. (–)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits pancreatic lipase and reduces body weight gain in high Fat-Fed obese mice. Obesity 20, 2311–2313. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2011.139 (2012).

Bose, M. et al. The major green tea polyphenol, (–)-Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate, inhibits obesity, metabolic syndrome, and fatty liver disease in High-Fat–Fed mice. J. Nutr. 138, 1677–1683. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/138.9.1677 (2009).

Sae-Tan, S., Grove, K. A., Kannett, M. J. & Lambert, J. D. (–)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate increases the expression of genes related to fat oxidation in the skeletal muscle of high fat-fed mice. Food Funct. 2, 111–116. https://doi.org/10.1039/C0FO00155D (2011).

Kapoor, M. P., Sugita, M., Fukuzawa, Y. & Okubo, T. Physiological effects of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) on energy expenditure for prospective fat oxidation in humans: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Nutr. Biochem. 43, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.10.013 (2017).

Talal, S. et al. High carbohydrate diet ingestion increases post-meal lipid synthesis and drives respiratory exchange ratios above 1. J. Exp. Biol. 224, jeb240010. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.240010 (2021).

Ribeiro, L. & Fonseca, C. L. C. Occurrence of lipoprotein lipase in the fat body of Triatoma maculata. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B. 52, 523–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-0491(75)90229-1 (1975).

Heusden, M. C. V. Characterization and identification of a lipoprotein lipase from Manduca sexta flight muscle. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 23, 785–792. https://doi.org/10.1016/0965-1748(93)90066-2 (1993).

Toprak, U., Hegedus, D., Doğan, C. & Güney, G. A journey into the world of insect lipid metabolism. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 88 https://doi.org/10.1002/arch.21682 (2020).

Canavoso, L. E. et al. FAT METABOLISM IN INSECTS. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 21, 23–46 (2001).

Slack, C., Foley, A. & Partridge, L. Activation of AMPK by the putative dietary restriction mimetic Metformin is insufficient to extend lifespan in Drosophila. PLOS One. 7, e47699. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0047699 (2012).

Vial, G., Detaille, D. & Guigas, B. Role of mitochondria in the Mechanism(s) of action of Metformin. Front. Endocrinol. 10, 294. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2019.00294 (2019).

Yoo, J. et al. Fenofibrate, a PPARα agonist, reduces hepatic fat accumulation through the upregulation of TFEB-mediated lipophagy. Metabolism 120, 154798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2021.154798 (2021).

Tennessen, J. M., Barry, W., Cox, J. & Thummel, C. S. Methods for studying metabolism in Drosophila. Methods 68, 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.02.034 (2014).

Mizoguchi, A. et al. A monoclonal antibody against a synthetic fragment of bombyxin (4K-prothoracicotropic hormone) from the silkmoth, Bombyx mori: characterization and immunohistochemistry. Mol .Cell. Endocrinol. 51, 227–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/0303-7207(87)90032-3 (1987).

Hanatani, S. et al. Acetate alters expression of genes involved in beige adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells and obese KK-Ay mice. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 59, 207–214. https://doi.org/10.3164/jcbn.16-23 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Atsumaru Holdings NSP Yamaga Plant, Atsumaru Yamaga Silk, for their kind gift of silkworms. We also thank Dr. Yasuhiko Matsumoto for his cooperation. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP23804033.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, YT; writing—review and editing, HPD; conceptualization, writing—review and editing, supervision, MY.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Murata, Y., Devkota, H.P. & Wada, M. Development of a silkworms-based evaluation system for the extracts and compounds for their obesity and lipid metabolism improving activity. Sci Rep 15, 17997 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96863-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96863-1