Abstract

Atherosclerosis is the major cause of cardiovascular diseases worldwide, and AIDS linked with chronic inflammation and immune activation, increases atherosclerosis risk. The application of bioinformatics and machine learning to identify hub genes for atherosclerosis and AIDS has yet to be reported. Thus, this study aims to identify the hub genes for atherosclerosis and AIDS. Gene expression profiles were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus database. The Robust Multichip Average was performed for data preprocessing, and the limma package was used for screening differentially expressed genes. Enrichment analysis employed GO and KEGG, protein–protein interaction network was constructed. Hub genes were filtered using topological and machine learning algorithms and validated in external cohorts. Then immune infiltration and correlation analysis of hub genes were constructed. Nomogram, receiver operating curve, and single-sample gene set enrichment analysis were applied to evaluate hub genes. This study identified 48 intersecting genes. Enrichment analyses indicated that these genes are significantly enriched in viral response, inflammatory response, and cytokine signaling pathways. CCR5 and OAS1 were identified as common hub genes in atherosclerosis and AIDS for the first time, highlighting their roles in antiviral immunity, inflammation and immune infiltration. These findings contributed to understanding the shared pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis and AIDS and provided possible potential therapeutic targets for immunomodulatory therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atherosclerosis (AS) is the major contributor to cardiovascular disease (CAD), the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide1. Current evidence suggests that AS is a complex process of plaque formation mediated by many risk factors2. The pathogenesis of AS was not only linked to dyslipidaemia and hypercholesterolaemia but also associated with the innate and adaptive immune systems including chemokine signalling activation and immune cells infiltration.

Meanwhile, the proportion of people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) died from non-AIDS-related diseases had increased with increasing duration of antiretroviral Therapy (ART)3. The ART and early treatment transformed acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) into a chronic health condition. Atherosclerosis became one of the major type of CAD occurring in people living with HIV.

Available studies shown that people living with HIV treated by ART had higher inflammatory markers level and thicker carotid intima-media thickness4. Some type of ART may be associated with increased risk of CAD, but the ART led risk of CAD still unclear5. Prior studies also indicated that the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis might be enhanced in the HIV infection6. Furthermore, people living with HIV often have more conventional CAD risk factors for example high rates of smoking7. The risk of atherosclerosis was increased in people living with HIV compared with uninfected persons8. Chronic inflammation and immune activation which played a more complex and important role in AIDS may contribute to this risk. Overall one important direction is exploring the underlying common pathogenesis and immune infiltration characteristics of AS and AIDS. In previous studies linking AS and AIDS, the main focus has been on the prevalence of AS and risk factors in people living with HIV. However, no bioinformatics has been applied to focus on the shared hub genes of AS and AIDS.

In recent years, the rapid development of bioinformatics has provided a new perspective to explore the potential hub genes for familiar diseases and to evaluate their immune characteristics using immune cell infiltration. Moreover, machine learning is helpful for assessing high-dimensional data and screening the hub genes of biological significance9,10. Overall, we can identify hub genes and assess their predictive performance more effectively and accurately, helping us discover potential diagnostic biomarkers for various diseases, including atherosclerosis, and investigate the etiological and pathological relationships between two diseases.

In comparison with prior research, we have linked AS with AIDS and investigated sharing hub genes for the first time, and applied machine learning for the screening of these hub genes for the first time. Furthermore, we have explored the relationship between these hub genes and immune cell infiltration. Our study offers new sights into AS and AIDS, potentially contributing to the treatment of both diseases.

Methods

Gene expression profiles

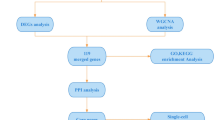

The study flowchart is illustrated in Fig. 1. Microarray datasets were obtained from the public repository NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) database11. The gene expression profiles utilized (GSE100927, GSE16363, GSE28829, GSE28160) were downloaded using “atherosclerosis” or “AIDS” as keywords. In addition, the selection of the GEO datasets was based on the quality control of R package “affy”; the sample size was sufficient, with at least 30 samples; and the experimental design was basely consistent: all datasets used similar platforms.

The GSE10092712 is generated by the GPL17077 platform and contains 29 samples from carotid arteries with atherosclerotic lesions and 12 samples from control carotid arteries, 26 samples from femoral arteries with atherosclerotic lesions and 12 samples from control femoral arteries,14 samples from infrapopliteal arteries with atherosclerotic lesions and 11 samples from control infrapopliteal arteries. The GSE100927 is divided into 69 atherosclerotic lesions samples and 35 control arteries without atherosclerotic lesions samples.

The GSE1636313 is generated by GPL570 platform and contains 10 lymphatic tissue samples from patients unaffected, 18 lymphatic tissue samples from patients with asymptomatic stages of AIDS, 16 lymphatic tissue samples from patients with acute stages of AIDS, and 8 lymphatic tissue samples from patients with AIDS. Then the GSE1636 was divided into 10 control samples and 42 AIDS samples.

The GSE2882914 for AS group and GSE28160 for AIDS group were utilized as external validation cohorts. The GSE28829 including 29 carotid artery samples, and was divided into 13 early intimal thickening and intimal xanthoma samples as control samples and 16 advanced thin or thick fibrous cap atheroma lesions as AS samples. The GSE2816015 is divided into 9 uninfected postmortem brain tissues as control samples and 26 HIV infection postmortem brain tissues as AIDS samples. Detailed information on the cohorts is shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs)

The raw data matrix needs to undergo necessary processing to obtain reliable clean gene expression matrix for analysis. After downloading datasets, background adjustment and quantile normalization were performed by the R package “affy” from the BioConductor project to preprocess gene expression matrix. The background adjustment used the Robust Multichip Average algorithm. And the Offset parameter was set to 50 to adjust the signal strength. When probes corresponded to the same gene symbol, the average value was determined as the gene expression value. After the probes were converted into official gene symbols, the gene expression matrix was completed. And probes without gene symbol were excluded. Then R “limma” package was utilized to conduct the differential gene expression analysis based on the criteria: adjusted P value < 0.05 and |log2 Fold change (FC)|> 1. Only the overlapping genes in both matrices could be selected for further analysis.

GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses

Enriched Gene Ontology (GO) terms (biological process, BP; cellular component, CC and molecular function, MF) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis of the selected overlapping DEGs were committed in the DAVID (the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery; https://david.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp)16,17,18,19. False discovery rate < 0.05 and P valve < 0.05 was chosen as the threshold. Finally, the functional enrichment results were visualized using R package “ggplot2” in each category.

Construction of the PPI network and hub genes pre-selection utilizing topological algorithms

The overlapping DEGs were constructed the protein–protein interaction (PPI) network to further explore potential interplay by the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (String) database (STRING version 12.0; https://cn.string-db.org/). The minimum required interaction score was 0.4. And the nodes without connections with others were hidden. Cytoscape software (version 3.10.1) was applied to display the relationship between proteins. To further identify hub genes, we use the Cytoscape plug-in CytoHubba for topological analysis by three different algorithms (Degree, Betweenness, and Closeness).The selected three algorithms can determine node importance in biological networks and identify central elements of biological networks based on network features. Finally, we choose the intersection of top 20 DEGs three topological algorithms as the pre-selected hub genes.

Hub genes identification utilizing three machine learning algorithms

To further screening of hub genes between AS and AIDS datasets, we applied three well-established machine learning algorithms (SVM-RFE: Support Vector Machine-Recursive Feature Elimination; LASSO: Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator; RF: Random Forest) for the pre-selected hub genes. And we set the same seed in both disease datasets in order to ensure the repeatability of these algorithms.

The SVM-RFE has excellent performance especially on two-group classification disease problems and is widely used to analyze data with an approximately equal number of predictors20. So firstly we applied SVM-RFE to determine the optimal hub gene by sequential backward feature elimination. And R package “e1071” was utilized for SVM modeling. The k parameter was set to 10 and halve.above parameter was set to 100. The result of SVM-RFE was visualized, and the point with the lowest tenfold cross-validation (10 × CV) error, indicated by a red circle, represented the maximum classification precision and the corresponding gene sets were the most valuable.

The LASSO was useful for filtering variables and preventing overfitting. Therefore, the pre-selected hub genes were input into LASSO algorithm in AS and AIDS datasets. R package “glmnet” was used for regression model and a tenfold cross-validation (10 × CV) was performed to adjust the optimal penalty parameter. We chose the best lambda value by “lambda.1 min”.

The RF which is an ensemble algorithm based on decision trees can identify the most important genes, and using pre-selected hub genes can enhance its performance. Thus, we used RF algorithm to screen the pre-selected hub genes with R package “randomForest”.We explored the optimal value of random forest trees and ultimately selected 500 trees for analysis. The intersection genes of top 10 increase in mean squared error (%lncMSE)and top 10 increase in node purity (lncNP) were considered as valuable hub genes.

After screening the above three algorithms, genes identified from the intersection of the three algorithms were considered hub genes.

Immune cell infiltration

The algorithm “CIBERSORT” can transform each normalized gene expression matrix into the immune cell composition. We used the R package “CIBERSORT” to quantify the proportions of 22 kinds of immune cells in both AS and AIDS datasets. The expression matrix for the immune infiltration analysis via algorithm “CIBERSORT” has ensured that the expression data have no negative values and are not log-transformed. For each sample, the output estimates were normalized to sum to 1 to facilitate comparisons across immune cell types and datasets. The proportion of each immune cell in each sample was visualized from the barplot. The comparison of expression of difference immune cell between disease group and control group was visualized by boxplot. Furthermore, the Spearman correlation coefficient was performed to assess the associations between immune infiltrated cells and hub genes based on criteria: p value < 0.05. In order to present the results clearly, only coefficients with P value less than 0.05 will be plotted.

ROC evaluation and nomogram construction

To assess the accuracy of hub genes, we took them as the target genes to construct receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and calculated area under the ROC curve (AUC) and 95% confidence interval (CI). The optimal AUC for predicting the events of AS and AIDS was > 0.8. The target genes expression pattern in both AS and AIDS datasets was also shown by violin plot. Following that, the nomogram was constructed using the R package “rms”. According to the contribution degree of each hub gene to the outcome variables (based on logistic regression), a score was assigned to each hub gene expression level. The summation of each score was referred to as total score, which can be the predicted value of the incidence of AS and AIDS.

Single-sample gene set enrichment analysis

To further reveal the hallmark specific well-defined biological states or processes of the hub genes, single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) was performed for each hub genes in the two disease groups based on the criteria: adjusted P value < 0.05 and |Normalized Enrichment Score (NES)|> 1via the R package “clusterProfiler”. Using ssGSEA, the correlation of hub genes and hallmark gene sets can be identified by Spearman correlation coefficient. MSigDB (h.all.v2023.2.Hs.entrez.gmt) was used to download the hallmark gene sets (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/human/collections.jsp#H). Then we obtained the hallmark specific well-defined biological states or processes for each gene in the two disease groups. Following that, enrichplot was used to show the top 5 normalized enrichment score (NES) activating and inhibiting pathways.

Prediction performance in validation cohort

The accuracy of each hub gene needed further test after hub genes were screened, we utilized the GSE28829 for external validation of AS group and GSE28160 for external validation of AIDS group. The raw data processes of validation cohorts used RMA algorithm. The hub genes relative expression pattern was shown by violin plot, and AUC was also calculated.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test, continuous variables were used in comparison between two groups. The data were presented as mean values accompanied by the standard error of the mean (SEM). The multiple test correction adopted for the identification and GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs was based on the Benjamini–Hochberg correction method. The permutation test was used in ssGSEA, and the Spearman correlation coefficient was used in the immune infiltrating cell correlation analysis. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. R software version 4.3.0, GraphPad Prism Version 9.5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) were used to perform statistical analyses.

Results

Identification of DEGs via limma

1156 DEGs with 757 up-regulated and 399 down-regulated were identified in AS groups. 179 DEGs with 148 up-regulated and 31 down-regulated were identified in AIDS groups. Volcano plots showed all DEGs of AS (Fig. 2A) and AIDS (Fig. 2B). The Venn plot showed the intersection of DEGs in each discovery cohort (Fig. 2C). Each discovery cohort contained up-regulated and down-regulated groups. Taken as a whole, the intersection of the DEGs (n = 48) contained in the two groups were visualized by heatmaps (Fig. 2D,E).

Identification of DEGs in AS and AIDS. (A) The volcano plot of all DEGs in AS group. (B) The volcano plot of all DEGs in AIDS group. (C) The Venn plot displays that the intersection of DEGs in AS and AIDS groups yielded 48 overlapping DEGs. (D) The heatmap plot of overlapping DEGs in AS group. (E) The heatmap plot of overlapping DEGs in AIDS group.

GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of overlapping DEGs

To explore the shared pathogenesis of AS and AIDS, we took the overlapping DEGs mentioned above on GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis with the help of DAVID. BP terms showed the DEGs were enriched in “response to virus”, “inflammatory response” and “defense response to virus” (Fig. 3A). In CC, the terms “extracellular region” and “external side of plasma membrane” were significantly enrichment (Fig. 3B). Therefore, we hypothesized that DEGs mainly influence extracellular. And DEGs were mainly enriched GO terms for MF in “chemokine activity” significantly (Fig. 3C). Moreover, we conducted KEGG pathway enrichment analysis with DAVID. The following KEGG pathway were “viral protein interaction with cytokine and cytokine receptor”, “Chemokine signaling pathway”, “Toll-like receptor signaling pathway” and “Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction” (Fig. 3D). The full results of enrichment analyses were showed in Supplementary Table 2.

The result of GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses. (A–C) GO analysis (BP, CC, M) of overlapping DEGs, The X-axis refers to the gene ratio, Y-axis represents the different ontologies, the circle size represents the gene counts, and the color indicates the significance. (D) KEGG pathways analysis of overlapping DEGs.

PPI network construction and hub gene pre-selection

The overlapping 48 DEG-encoded proteins and their interactions among each other can be valuable clue to understand a system-wide of cellular function21. PPI network of above DEGs was analyzed using the STRING database (Supplementary Fig. 1). After eliminating DEG-encoded proteins with poor interaction (n = 6), 42 DEGs were retained and visualized by the Cytoscape (Supplementary Fig. 2A). To have a more credible result, three topological algorithms(Closeness, Degree and Betweenness) were utilized to screen hub genes (Supplementary Fig. 2B–D). Then we intersected the results of top 20 three topological algorithms (Supplementary Table 3). Finally, 15 hub genes were obtained after pre-selection (Supplementary Fig. 2E).

Identify hub genes based on machine learning algorithms

To select hub genes for further analysis, three different algorithms were applied based on the above 15 hub genes. The SVM-RFE identified 13 genes in AS group and 15 genes in AIDS group (Fig. 4A,B). The LASSO results in AS and AIDS groups are shown in Fig. 4C,D. Based on optimal tuning parameter, λ was set at 0.005360178 (AS group) and 0.001662953 (AIDS group). The results of RF algorithms in AS and AIDS groups included top 10 increase in mean squared error (%lncMSE) and top 10 increase in node purity (lncNP) are shown in Fig. 4E,F. Finally, we intersected the results of three algorithms (Supplementary Table 4),and a Venn plot (Fig. 4G) showed the hub genes(CCR5 and OAS1).

The CCR5 and OAS1 were selected as hub genes using three machine learning algorithms. (A) Based on SVM-RFE, 13 genes were identified in AS group. (B) Based on SVM-RFE, 15 genes were identified in AIDS group. (C) 9 genes were selected based on LASSO in AS group. (D) 10 genes were selected based on LASSO in AIDS group. (E) The results of RF ranked by %lncMSE and lncNP in AS group. (F) The results of RF ranked by %lncMSE and lncNP in AIDS group. (G) The Venn plot showed that CCR5 and OAS1 were selected.

Immune infiltration analysis and correlation analysis of hub genes

The proportion of 22 immune cells in each sample was shown as a staked bar plot (Fig. 5A,B). There were significant differences in immune cell infiltration were observed in AS group and AIDS group (Fig. 5C,D).

AS and AIDS immune cell composition. (A) The proportion of immune cells infiltrating the samples in AS group. (B) The proportion of immune cells infiltrating the samples in AIDS group. (C) Differences in infiltration of immune cells between AS and control samples. (D) Differences in infiltration of immune cells between AIDS and control samples. (E) Correlation analysis of immune cells with OAS1 and CCR5 in AS group. (F) Correlation analysis of immune cells with OAS1 and CCR5 in AIDS group. *P < 0.05;**P < 0.01;***P < 0.001;****P < 0.0001.

In AS group, the significant increase in memory B cells and follicular helper T cells suggest chronic antigen exposure, likely driven by oxidized low-density lipoprotein which is a key autoantigen in AS22. Follicular helper T cells promote germinal center reactions and foster autoantibody production against vascular antigens, which exacerbates plaque inflammation23. Paradoxically, the reducing of plasma cells may reflect impaired B cells differentiation due to disrupted tolerance checkpoints23. The increased gamma delta T cells can secrete proinflammatory cytokine which contributes to endothelial dysfunction and plaque instability. The accumulation of M0 macrophages and reduced M1 and M2 macrophages subsets indicate defective polarization. M0 macrophages release matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), destabilizing fibrous caps, while diminished M2 macrophages impair anti-inflammatory repair mechanisms24. Moreover, activated mast cells release histamine and proteases, directly damaging endothelial integrity and promoting intraplaque hemorrhage which is a hallmark of advanced AS.

In AIDS group, the HIV replication drives CD8 T cells. The significant increase of neutrophils further amplifies inflammation through neutrophil extracellular trap formation which can accelerate vascular damage25. The depletion of naive and resting memory CD4 T cells reflects HIV-induced apoptosis and the HIV latent reservoir26. Meanwhile, the increased activated memory CD4 T cells exacerbate systemic inflammation including atherosclerosis. Moreover increased M1 macrophages correlate with the release of proinflammatory cytokine. Similar to the AS group, M2 macrophages reduction impairs tissue repair and worsens vascular remodeling.

Moreover, the correlation analyses of immune infiltrated cells were investigated. Supplementary Fig. 3A shows that in AS group B cells had the top positive correlation with resting memory CD4 T cells (r = 0.59) and neutrophils had the top positive correlation with resting NK cells (r = 0.59) at same time. Meanwhile, M0 macrophages had the greatest negative correlation with resting memory CD4 T cells (r = − 0.78). Supplementary Fig. 3B shows that in AIDS group, resting memory CD4 T cells had the highest positive correlation with naive CD4 T cells (r = 0.79),while resting memory CD4 T cells had the largest negative correlation with gamma delta T cells (r = − 0.83).

Following that, the correlation analysis between immune infiltrated cells and hub genes was investigated. In AS group (Fig. 5E), OAS1 was significantly positively correlated with inflammatory immune cells (e.g., memory B cells, follicular helper T cells, gamma delta T cells, M0 macrophages and activated mast cells), whereas it was negatively correlated with resting state or anti-inflammatory related cells (e.g., resting memory T cells, M2 macrophages). OAS1 may promote the recruitment of inflammatory immune cells through the interferon signaling pathway. CCR5 was significantly positively correlated with gamma delta T cells, M0 macrophages and activated mast cells, whereas it was negatively correlated with plasma cells, resting memory T cells and M2 macrophages. These suggested that CCR5 may promote vascular inflammation and inhibit anti-inflammatory related cells possibly through chemokines.

In AIDS group (Fig. 5F), activated memory CD4 T cells, neutrophils and M1 macrophages were positively correlated with OAS1, suggesting activation of antiviral immunity and macrophage polarization. While resting memory CD4 T cells and M2 macrophages were correlated negatively with OAS1. CCR5 was significantly positively correlated with CD8 T cells, neutrophils, activated memory CD4 T cells, gamma delta T cells and M1 macrophages, whereas it was negatively correlated with Memory B cells, naive CD4 T cells, resting memory CD4 T cells, resting NK cells and M2 macrophages. This may be indicated that CCR5 as an HIV co-receptor is both an accomplice to viral invasion and a facilitator of inflammatory cell migration. Additionally, under HIV infection, some immune cells such as neutrophils and M1 macrophages may be promoted to recruit toward inflammation and positively correlate with multiple markers.

Diagnostic value evaluation and nomogram construction

The three machine learning algorithms identified OAS1 and CCR5 as hub genes. Compared with the control, OAS1 and CCR5 were upregulated in AS group (Fig. 6A). As shown in the violin plot (Fig. 6B), the upregulation of OAS1 and CCR5 was more significant in AIDS group. Following that, the nomogram models for diagnosing AS and AIDS based on OAS1 and CCR5 were constructed via the R package “rms” (Fig. 6C,D). The nomogram model showed that CCR5 was associated with a high risk of AS, while in AIDS group, the nomogram model indicated that OAS1 and CCR5 had a high predictive value for diagnosing AIDS. ROC curve analysis also showed a high diagnostic value of hub genes: in AS group (Fig. 6E), OAS1 (AUC 0.9043, 95% CI 0.8468–0.9619), CCR5 (AUC 0.9416, 95% CI 0.8983–0.9850); in AIDS group (Fig. 6F), OAS1 (AUC 1.000, 95% CI 1.000–1.000), CCR5 (AUC 1.000, 95% CI 1.000–1.000). Although the ROC analysis results of the AIDS group demonstrated the ideal predictive value of hub genes, the results need to be further validated due to the limited number of samples included.

The diagnostic value evaluation and nomogram construction. (A,B) The violin plot showed expression of hub genes in AS and AIDS groups (A: the AS group; B: the AIDS group). (C,D) Nomogram was used to predict the occurrence of AS and AIDS. (C: the AS group; B; the AIDS group). (E,F) The ROC curve of AS and AIDS groups. Each panel displayed the AUC under the curve (E: the AS group; F; the AIDS group).

Single-sample GSEA of hub genes

To reveal the potential functions of the two hub genes, ssGSEA in AS and AIDS groups was performed. Supplementary Table 5 showed the ssGSEA results completely. Following that, the top 3 NES activating and inhibiting pathways based on CCR5 and OAS1 in each disease group were visualized in Fig. 7. The two hub genes were both enriched in immune related pathways in the AS and AIDS group, such as interferon response, complement system and inflammatory response. Besides, CCR5 and OAS1 both enriched in cell cycle related pathways and signaling pathways including IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signaling and growth factor beta (TGF-β) signaling.

Validation of hub genes

In validation cohorts, we confirmed the accuracy of hub genes (CCR5 and OAS1) for AS and AIDS. In the external validation cohort of AS group, the relative expression levels of CCR5 and OAS1 were significantly upregulated (Supplementary Fig. S4A). Similarly, in the external validation cohort of AIDS group, Supplementary Fig. S4B showed the significant upregulation of CCR5 and OAS1. Following that, the ROC curve analysis showed good predictive performance of each hub gene in AS and AIDS validation cohorts(Supplementary Fig. S4C,D). The above results confirmed that CCR5 and OAS1 had a good diagnostic value as hub genes for AS and AIDS, respectively.

Discussion

In our study, we obtained the overlapping genes in AS and AIDS through an integrated approach of bioinformatics analysis for the first time, leading to the identification of two hub genes(CCR5 and OAS1), which were found to be significantly implicated in the pathogenesis of both AS and AIDS.

The AIDS discovery cohort we have incorporated was based on lymphatic tissue as the sampled tissue applied to microarray analysis, with the AIDS group being HIV-infection, while the control group was all derived from individuals uninfected. And the AIDS validation cohort we selected consists of post-mortem brain tissues, with this non-immunological organ serving as the sampled tissue. This is attributed to the fact that, for patients with AIDS, the target organs influenced by HIV are system-wide. And there were significant differences in gene expression observed in numerous tissues and organs, including lymph nodes and brain tissues.

Meanwhile, the AS discovery and validation cohorts selected in our study were derived from plaque or non-pathological tissue samples. The AS validation cohort we selected consists of early pathological intimal thickening and intimal xanthoma as control group, with advanced thin or thick fibrous cap atheroma lesions as AS group. The selected AS validation cohort was intended to further substantiate the involvement of hub genes in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and confirm their diagnostic and predictive values.

During the GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of overlapping genes in AS and AIDS, we found that the enrichment terms associated with immune were mainly lies in immune cells including Natural killer (NK) cells, monocytes, dendritic cells and related signaling pathway including chemokine-mediated, toll-like receptor and interleukin-27-mediated signaling pathway. NK cells were regard as innate immune cells, which play a critical role in response to virus including coordinating and executing the elimination of virus-infected cells27, and have been shown to be involved in preventing HIV infection. In AS group, the biological process results about NK cells also exhibited a crucial role in AS pathogenesis, the symptomatic carotid plaques were identified infiltrating by a higher number of NK cells28. The activation of monocytes was likewise associated with plaque development. And the level of monocytes/macrophage inflammation markers were higher among people living with HIV and associated with the formation of new focal carotid artery plaque29. Meanwhile the activity of monocytes and T cells may contributed to vascular defects which leading atherosclerosis in pathogenesis of AIDS30. The elevated levels of chemokines in people living with HIV may contributed to transformation of foam cells via migrating monocytes, leading to vulnerable plaques31. We detected the level of dendritic cells was decreased both in atherosclerosis and AIDS goups by immune infiltration.

The enrichment analysis associated with signaling pathway ties with previous study. The toll-like receptors signaling pathway participated in defending against infection and induced inflammatory cytokines and interferons32. In atherosclerosis environment fatty materials trigger the cytokine Interleukin-27 (IL-27) from dendritic cells (DCs) by Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) dependent manner33. IL-27 can significantly enhance adhesion molecules, inflammatory cytokine and chemokines in arterial endothelial cells34, which contributes to the infiltration of inflammatory immune cells into the lesions. Meanwhile the plasma IL-27 titer was significantly elevated in people living with HIV and positively correlated with CD4 T cells count35. IL-27-mediated signaling pathway has been reported that may be involved in the pathogenesis of HIV and immune reconstitution via regulating T helper cells1/T helper cells 2 ratio in HIV-infection36. Taken all to consideration, these findings suggested that these overlapping DEGs were linked with higher inflammation level and immune activation. Our enrichment analysis supports the numerous literature implicating elevated levels of inflammation as crucial pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and AIDS.

In the present study, we first applied the machine learning algorithms and identified CCR5 and OAS1 as hub genes in the two diseases. C–C motif chemokine receptor 5(CCR5) is a protein coding gene that encodes CCR5. CCR5 is a G protein-coupled receptor of the beta chemokine receptor family which regulates memory/effector T cells, macrophages, and immature dendritic cells37 and plays a crucial role in directing in homeostasis, immune surveillance and inflammation38. CCR5 may have common impact mechanisms in atherosclerosis and AIDS39,40 and involved the regulation of inflammation response by influencing T cells movement and adhesion, promoting T cells polarization and producing inflammatory mediators41,42,43. Besides, CCR5 may increased risk of atherosclerosis by activating monocytes to express transcription factors (TF) through innate immune receptor recognition in HIV-infection44. Meanwhile, CCR5 regulated cell apoptosis and proliferation. Previous studies found that CCR5 correlated with CD4 T cells apoptosis and T cells activation at same time45,46, thereby may affected progression of atherosclerosis and AIDS. A further novel finding is that CCR5 may be possible potential therapeutic targets in atherosclerosis. In mouse models, the CCR5 inactivation has protective effects across atherosclerotic endpoints including plaque growth and calcification47. Deletion of CCR5 reduced macrophage expression of MMP-9 which was contributed to atherosclerosis48. And another study shown that inhibition of CCR5 abrogated arterial macrophage accumulation and led lower circulating monocytes49. Fortunately the CCR5Delta32 (the natural knock-down of CCR5) allows us to discover association between CCR5 and human atherosclerosis. The CCR5Delta32 individuals associated with higher density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and lower triglycerides both in plasma50,and also associated with lower C-reactive protein and decreased intima-media thickness51. Another study supported that CCR5Delta32 linked with lower risk of severe coronary artery disease52. Furthermore, CCR5 predominated the chemokine co-receptors used by HIV-1 for cell entry53. Previous study shown that the CCR5 antagonist maraviroc has antiviral activity against HIV-154. Maraviroc treatment may improves inflammatory process in HIV-1 and has protective and anti-inflammatory on CAD55. Considering that there is a higher risk of CAD in people living with HIV, CCR5 blockade will hopefully become a relatively harmless therapeutic option for inflammatory disease and infection.

2′-5′-Oligoadenylate Synthetase 1 (OAS1) is a protein coding gene that encodes an interferon-induced antiviral enzyme which plays a crucial role in innate cellular antiviral response56 and other cellular processes including apoptosis and cell growth. As the member of oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS) family, the higher oligomers of OAS1 can bind to ribonuclease L (RNase L) and leading activation. The activated RNase L leads degradation of viral RNA and cell, contributing to the inhibition of protein synthesis and termination viral replication57,58. Besides, it has been reported that mouse 2′-5′-Oligoadenylate Synthetase-like 1 (OASL1) boosted the production of type I Interferon by regulating transcription factor IRF7, resulting in inflammatory responses59. The expression of OASL1 participates in the inflammatory related diseases including cancer, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis in mouse experiment60,61. Moreover, the OAS level in human was also linked to inflammatory related diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis and systemic sclerosis62. The single-cell transcriptomic data from the model organism mus musculus shown that OASL1 was expressed by aortic endothelial cells63,64, suggesting OASL1 may participated in inflammatory vascular diseases such as atherosclerosis. The mouse endothelial expression pattern of OASL1 was similar to human OASL. A genome-wide association study confirmed that OASL affected multiple cardiovascular-related traits65. Human OASL levels were higher in atherosclerotic aorta tissues with plaques, and OASL contributes to a protective function against atherosclerosis by maintaining endothelial nitric oxide synthase mRNA stability66. In light of this, one important and promising direction is that OAS1 may be a biomarker to monitor the effect of therapy for inflammatory related diseases and infections and may leads to new treatment strategies.

In summary, the identification of CCR5 and OAS1 as hub genes provides new perspectives. In the future, clinical evaluation of AS in people living with HIV treated with maraviroc, an antagonist of CCR5, could be performed. Small molecule drugs that target OAS1 can be predicted, and the expression pattern of OAS1 can be further investigated in relevant models.

However, several limitations need to be mentioned in our study. First, the datasets of our study are mainly microarray which was not nowadays advanced sequencing technology. The preset probes may not cover all genes and may miss some infrequent genes. The extremely highly expressed genes may cause quantification bias due to signal saturation. Second, the hub genes we identified were validated by other datasets and not in cell or animal models. The characters of these public datasets may lead to decline in the credibility of our study. For example, the tissue heterogeneity in AIDS discovery and validation cohorts may introduce uncertainty. Third, our study focused on overlapping genes between AS and AIDS which may inadvertently obscure disease-specific mechanisms. The differences in immune cell composition suggest distinct drivers of AS. For instance, people living with HIV tend to have soft plaque and less calcification. Future studies integrating differential cell-type transcriptomics are needed to dissect how AS and AIDS diverge in vascular inflammation.

Conclusion

This study has identified CCR5 and OAS1 as common hub genes for AS and AIDS via bioinformatics analysis and machine learning algorithms for the first time. The performance of two hub gene in the external validation was reliable, which enhances our confidence in the results. The results of this study indicates CCR5 and OAS1 have significant roles in inflammation and immune infiltration. These findings contributed to understanding the shared pathogenesis of AS and AIDS and provided possible potential therapeutic targets for immunomodulatory therapy. Future studies warrant appropriate small molecule drug prediction for CCR5 and OAS1, alongside validation of CCR5 and OAS1 regulatory networks in relevant models.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyses during the current study are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) with the accession number: GSE100927, GSE16363, GSE28829, GSE28160.

References

Roth, G. A. et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: Update from the GBD 2019 Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 76, 2982–3021 (2020).

Roy, P., Orecchioni, M. & Ley, K. How the immune system shapes atherosclerosis: roles of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 22, 251–265 (2022).

Causes of death in HIV-1-infected patients treated with antiretroviral therapy, 1996–2006: Collaborative analysis of 13 HIV cohort studies. Clin. Infect. Dis. 50, 1387–1396 (2010).

Ross, A. C. et al. Relationship between inflammatory markers, endothelial activation markers, and carotid intima-media thickness in HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 49, 1119–1127 (2009).

Bavinger, C. et al. Risk of cardiovascular disease from antiretroviral therapy for HIV: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 8, e59551 (2013).

Hsue, P. Y. Mechanisms of cardiovascular disease in the setting of HIV infection. Can. J. Cardiol. 35, 238–248 (2019).

Saumoy, M. et al. Randomized trial of a multidisciplinary lifestyle intervention in HIV-infected patients with moderate-high cardiovascular risk. Atherosclerosis 246, 301–308 (2016).

Boccara, F. Cardiovascular complications and atherosclerotic manifestations in the HIV-infected population: Type, incidence and associated risk factors. AIDS 22(Suppl 3), S19-26 (2008).

Uddin, S., Khan, A., Hossain, M. E. & Moni, M. A. Comparing different supervised machine learning algorithms for disease prediction. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 19, 281 (2019).

Choi, R. Y., Coyner, A. S., Kalpathy-Cramer, J., Chiang, M. F. & Campbell, J. P. Introduction to machine learning, neural networks, and deep learning. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 9, 14 (2020).

Barrett, T. et al. NCBI GEO: Archive for functional genomics data sets–update. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D991-995 (2013).

Steenman, M. et al. Identification of genomic differences among peripheral arterial beds in atherosclerotic and healthy arteries. Sci. Rep. 8, 3940 (2018).

Li, Q. et al. Microarray analysis of lymphatic tissue reveals stage-specific, gene expression signatures in HIV-1 infection. J. Immunol. 183, 1975–1982 (2009).

Döring, Y. et al. Auto-antigenic protein-DNA complexes stimulate plasmacytoid dendritic cells to promote atherosclerosis. Circulation 125, 1673–1683 (2012).

Borjabad, A. et al. Significant effects of antiretroviral therapy on global gene expression in brain tissues of patients with HIV-1-associated neurocognitive disorders. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002213 (2011).

Sherman, B. T. et al. DAVID: A web server for functional enrichment analysis and functional annotation of gene lists (2021 update). Nucleic Acids Res. 50, W216-w221 (2022).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: Biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D672-d677 (2025).

Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951 (2019).

Huang, M.-L., Hung, Y.-H., Lee, W. M., Li, R. K. & Jiang, B.-R. SVM-RFE based feature selection and taguchi parameters optimization for multiclass SVM classifier. Sci. World J. 2014, 795624 (2014).

Szklarczyk, D. et al. The STRING database in 2017: Quality-controlled protein-protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D362-d368 (2017).

Mosalmanzadeh, N. & Pence, B.D. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein and its role in immunometabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 (2024).

Khan, A., Roy, P. & Ley, K. Breaking tolerance: The autoimmune aspect of atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 24, 670–679 (2024).

Bräuninger, H. et al. Matrix metalloproteinases in coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. Basic Res. Cardiol. 118, 18 (2023).

Hmiel, L. et al. Inflammatory and immune mechanisms for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in HIV. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 7266 (2024).

Chvatal-Medina, M. et al. Molecular mechanisms by which the HIV-1 latent reservoir is established and therapeutic strategies for its elimination. Arch. Virol. 168, 218 (2023).

Cerwenka, A. & Lanier, L. L. Natural killer cell memory in infection, inflammation and cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 16, 112–123 (2016).

Bonaccorsi, I. et al. Symptomatic carotid atherosclerotic plaques are associated with increased infiltration of natural killer (NK) cells and higher serum levels of NK activating receptor ligands. Front. Immunol. 10, 1503 (2019).

Hanna, D. B. et al. Association of macrophage inflammation biomarkers with progression of subclinical carotid artery atherosclerosis in HIV-infected women and men. J. Infect. Dis. 215, 1352–1361 (2017).

Matzen, K. et al. HIV-1 Tat increases the adhesion of monocytes and T-cells to the endothelium in vitro and in vivo: Implications for AIDS-associated vasculopathy. Virus Res. 104, 145–155 (2004).

Kearns, A., Gordon, J., Burdo, T. H. & Qin, X. HIV-1-associated atherosclerosis: Unraveling the missing link. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 69, 3084–3098 (2017).

Kumar, H., Kawai, T. & Akira, S. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 388, 621–625 (2009).

Ryu, H. et al. Atherogenic dyslipidemia promotes autoimmune follicular helper T cell responses via IL-27. Nat. Immunol. 19, 583–593 (2018).

Qiu, H. N., Liu, B., Liu, W. & Liu, S. Interleukin-27 enhances TNF-α-mediated activation of human coronary artery endothelial cells. Mol. Cell Biochem. 411, 1–10 (2016).

He, L., Zhao, J., Gan, Y.-X., Chen, L. & He, M.-L. Upregulation of interleukin-27 expression is correlated with higher CD4+ T cell counts in treatment of naïve human immunodeficiency virus-infected Chinese. J. AIDS HIV Res. 3, 6–10 (2011).

Zheng, Y. H. et al. The role of IL-27 and its receptor in the pathogenesis of HIV/AIDS and anti-viral immune response. Curr. HIV Res. 15, 279–284 (2017).

Oppermann, M. Chemokine receptor CCR5: Insights into structure, function, and regulation. Cell Signal 16, 1201–1210 (2004).

Li, J. & Ley, K. Lymphocyte migration into atherosclerotic plaque. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 35, 40–49 (2015).

Jones, K. L., Maguire, J. J. & Davenport, A. P. Chemokine receptor CCR5: From AIDS to atherosclerosis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 162, 1453–1469 (2011).

Funderburg, N. T. et al. Shared monocyte subset phenotypes in HIV-1 infection and in uninfected subjects with acute coronary syndrome. Blood 120, 4599–4608 (2012).

Sharapova, T. N., Romanova, E. A., Sashchenko, L. P. & Yashin, D. V. Tag7-Mts1 complex induces lymphocytes migration via CCR5 and CXCR3 receptors. Acta Naturae 10, 115–120 (2018).

Orlova-Fink, N. et al. Preferential susceptibility of Th9 and Th2 CD4+ T cells to X4-tropic HIV-1 infection. AIDS 31, 2211–2215 (2017).

Ebert, L. M. & McColl, S. R. Up-regulation of CCR5 and CCR6 on distinct subpopulations of antigen-activated CD4+ T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 168, 65–72 (2002).

Teer, E., Joseph, D. E., Glashoff, R. H. & Faadiel Essop, M. Monocyte/macrophage-mediated innate immunity in HIV-1 infection: From early response to late dysregulation and links to cardiovascular diseases onset. Virol. Sin. 36, 565–576 (2021).

Murooka, T. T. et al. CCL5-CCR5-mediated apoptosis in T cells: Requirement for glycosaminoglycan binding and CCL5 aggregation. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 25184–25194 (2006).

Joshi, A. et al. CCR5 promoter activity correlates with HIV disease progression by regulating CCR5 cell surface expression and CD4 T cell apoptosis. Sci. Rep. 7, 232 (2017).

Quinones, M. P. et al. CC chemokine receptor 5 influences late-stage atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 195, e92-103 (2007).

Wu, Y. et al. MMP-9 expression profile in inflammatory cells of Mip-1alpha knockout mice and Mip-1alpha receptor knockout mice. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 40, 374–377 (2009).

Combadière, C. et al. Combined inhibition of CCL2, CX3CR1, and CCR5 abrogates Ly6C(hi) and Ly6C(lo) monocytosis and almost abolishes atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolemic mice. Circulation 117, 1649–1657 (2008).

Hyde, C. L. et al. Genetic association of the CCR5 region with lipid levels in at-risk cardiovascular patients. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 3, 162–168 (2010).

Afzal, A. R. et al. Common CCR5-del32 frameshift mutation associated with serum levels of inflammatory markers and cardiovascular disease risk in the Bruneck population. Stroke 39, 1972–1978 (2008).

Szalai, C., et al. Involvement of polymorphisms in the chemokine system in the susceptibility for coronary artery disease (CAD). Coincidence of elevated Lp(a) and MCP-1 −2518 G/G genotype in CAD patients. Atherosclerosis 158, 233–239 (2001).

Lusso, P. HIV and the chemokine system: 10 years later. Embo J. 25, 447–456 (2006).

Dorr, P. et al. Maraviroc (UK-427,857), a potent, orally bioavailable, and selective small-molecule inhibitor of chemokine receptor CCR5 with broad-spectrum anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 4721–4732 (2005).

Woollard, S. M. & Kanmogne, G. D. Maraviroc: A review of its use in HIV infection and beyond. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 9, 5447–5468 (2015).

Wickenhagen, A. et al. A prenylated dsRNA sensor protects against severe COVID-19. Science 374, eabj3624 (2021).

Zhu, J., Ghosh, A. & Sarkar, S. N. OASL-a new player in controlling antiviral innate immunity. Curr. Opin. Virol. 12, 15–19 (2015).

Zhu, J. et al. Antiviral activity of human OASL protein is mediated by enhancing signaling of the RIG-I RNA sensor. Immunity 40, 936–948 (2014).

Lee, M. S., Kim, B., Oh, G. T. & Kim, Y. J. OASL1 inhibits translation of the type I interferon-regulating transcription factor IRF7. Nat. Immunol. 14, 346–355 (2013).

Sim, C. K. et al. 2’-5’ Oligoadenylate synthetase-like 1 (OASL1) deficiency in mice promotes an effective anti-tumor immune response by enhancing the production of type I interferons. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 65, 663–675 (2016).

Choi, B. Y. et al. 2’-5’ oligoadenylate synthetase-like 1 (OASL1) deficiency suppresses central nervous system damage in a murine MOG-induced multiple sclerosis model. Neurosci. Lett. 628, 78–84 (2016).

de Freitas Almeida, G. M. et al. Differential upregulation of human 2’5’OAS genes on systemic sclerosis: Detection of increased basal levels of OASL and OAS2 genes through a qPCR based assay. Autoimmunity 47, 119–126 (2014).

Single-cell transcriptomics of 20 mouse organs creates a Tabula Muris. Nature 562, 367–372 (2018).

A single-cell transcriptomic atlas characterizes ageing tissues in the mouse. Nature 583, 590–595 (2020).

Middelberg, R. P. S. et al. Genetic variants in LPL, OASL and TOMM40/APOE-C1-C2-C4 genes are associated with multiple cardiovascular-related traits. BMC Med. Genet. 12, 123 (2011).

Kim, T. K. et al. 2’-5’ oligoadenylate synthetase-like 1 (OASL1) protects against atherosclerosis by maintaining endothelial nitric oxide synthase mRNA stability. Nat. Commun. 13, 6647 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the participants for their cooperation and are grateful for the support of Department of Ultrasound, The People’s Hospital of Liaoning Province.

Funding

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82371982 to D.S.), Shenyang Middle younger Scientific and Technological Innovation Support Plan (RC220223 to D.S.), Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (2022-MS-078 to D.S. and 2023-MS-053 to Y.W.), and the Science and Technology Foundation of Shenyang Bureau (21-172-9-05 to P.Z.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.S. conceived and designed the study. D.S. and P.Z. supervised the study. Q.Z. and Y.W. wrote the main manuscript text. Q.Z., Y.W., X.Z. established the analytical strategy and analysed the data. X.Z., Y.Z., Z.Z. and B.L. assisted with data analysis and performed validation. All authors contributed to the conceptualization, writing of the original draft, as well as the review and editing of the final version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, Q., Wu, Y., Zhang, X. et al. Analysis and validation of hub genes for atherosclerosis and AIDS and immune infiltration characteristics based on bioinformatics and machine learning. Sci Rep 15, 12316 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96907-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96907-6